John Claridge’s Boxers (Round One)

Photographer John Claridge returned to the East End recently to visit the London Ex-Boxers Association and take portraits of the members. Coming from a family of boxers and being an ex-boxer himself, John possesses a natural empathy with these spirited men who were once the fiercest of opponents but are now the closest of friends.

Johnny Barnham (First fight 1950 – last fight 1955)

Ron Whittham (First fight 1950 – last fight 1961)

Joey Khan (First fight 1950 – last fight 1955)

Dynamo Colin Dunne (First fight 1993 – last fight 2003)

Peter Cragg (First fight 1966 – last fight 1970)

Sylvester Mittee (First fight 1977 – last fight 1988)

Ronnie Smith (First fight 1956 – last fight 1966)

Sammy McCarthy (First fight 1946 – last fight 1957)

Billy Graydon (First fight 1949 – last fight 1960)

Ron Cooper (First fight 1944 – last fight 1953)

Dave Cooper (First fight 1966 – last fight 1972)

Paul Fairweather, Committee Member of London Ex-Boxers ( fought in 1965)

Photographs copyright © John Claridge

You may like to read these boxing stories

Sylvester Mittee, Welterweight Champion

Ron Cooper, Lightweight Champion

Sammy McCarthy, Flyweight Champion

and take a look at these other pictures by John Claridge

Along the Thames with John Claridge

At the Salvation Army with John Claridge

A Few Diversions by John Claridge

Signs, Posters, Typography & Graphics

Views from a Dinghy by John Claridge

In Another World with John Claridge

A Few Pints with John Claridge

Some East End Portraits by John Claridge

Sunday Morning Stroll with John Claridge

The Doors Of Old London

The door to Parliament

Look at all the doors where the dead people walked in and out. These are the doors of old London. Some are inviting you in and some are shutting you out. Doors that lead to power and doors that lead to prison. Doors that lead to the parlour, doors that lead to the palace, and doors that lead to prayer. These are the doors that I found among hundreds of glass slides once used for magic lantern shows by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society, many more than a century old, and housed today at the Bishopsgate Institute.

Looking at life through a doorway, we are all either on the way in or on the way out. Like the door to your childhood home that got sold long ago, each one pictured here is evidence of the transient nature of existence, reminding you that you cannot go back through the portal of time.

Yet there is a powerful enigma conjured by these murky pictures of old doors, most of which will never open again. Like the pauper or the lost soul condemned to wander the streets, we cannot enter to learn what lies behind these doors of old London. But a closed door is an invitation to the imagination and we can wonder and dream, entering those hidden spaces in our fancy.

London has always been a city of doors, inviting both the curiosity and the suspicion of the passerby. In each street, there is a constant anticipation of people popping out, regurgitated onto the street by the building, and the glimpse to be snatched of the interior before the door closes again.

I cannot resist the notion that every door contains a mystery and all I need is a skeleton key. Then we can set out to explore as we please, going in one door and out another, until we have passed through all the doors of old London.

The entrance to the Carpenters’ Hall

The doors of Lambeth Palace

Door in the cloisters in Westminster Abbey

The door to the chamber of Little Ease at the Tower of London.

In St Benet’s Church, Paul’s Wharf.

Back door of 33 Mark Lane

Back door to Lancaster House.

In Crutched Friars.

14 Cavendish Sq.

The door to 10 Downing St

39a Devonshire St.

The door to the House of Lords

Wren doorway, Kensington Palace.

The door to Westminster Abbey

St Dunstan’s in the West

The entrance to Christ Church, Greyfriars.

The door to St Bartholomew’s, Smithfield

Temple Church

The Watchhouse, St Sepulcre’s, Smithfield.

Door by Inigo Jones at St Helen’s Bishopsgate.

Prior Bolton’s Door at St Bartholomew the Great.

At the Tower of London

Glass slides © Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

The Leather Shops of Brick Lane

Everything at Oceanic Leather is made in Brick Lane

Not so long ago, almost all the shops north of the railway bridge in Brick Lane sold leather jackets and bags manufactured locally, but now there are only a handful of these businesses left. So Spitalfields Life Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie and I went along to find out what is going on in the world of East End leather, and we encountered an entire spectrum of human emotion.

The manufacture of leather garments is an age-old industry on this side of London, existing as part of the clothing and textile trade that was a major source of employment here for centuries. A hundred years ago, the industry was predominantly Jewish but when Asian people arrived in significant numbers in the last century they worked as machinists in a trade that they eventually took over and now, a generation later, they find themselves presiding over its slow demise.

At Truth Trading, 151 Brick Lane, I encountered the father and son in a family business that began in 1978, sitting facing each other across a desk in an empty shop. “It’s dead! I make but I can’t sell,” declared Abdul Bari, leaping up almost apoplectic with frustration at the seventeen pounds they had taken that day, while his son sat watching with visible concern for his father’s distress. A skilled man who trained as a cutter and knew everything there is to know about the making of leather garments, Abdul Bari worked in the trade locally since 1968. Then he started making clothes at home before opening a shop in Commercial St, graduating through premises in Wentworth St and Bell Lane, then purchasing the Brick Lane premises in 1986. “We have a factory in Pakistan with one hundred sewing machines but it is closed down because there are no orders,” he lamented, leaving me searching for words that might console him.

Across the road in the compact corner shop packed with glistening leather, Open Space, 200 Brick Lane, Mohammed Kamran was resolutely cheerful, explaining that his uncle Mohammed Yusuf Nagory started the business, making leather jeans and selling them at Kensington Market in the seventies. Moving to Brick Lane in the eighties, he started a factory with twenty-five people in Cheshire St which his nephew joined at fifteen years old. Today, as a smaller business they are sustained by loyal customers and have recently made costumes for Harry Potter and the West End theatre. Astonishingly, you can buy a handmade leather jacket there for as little as thirty-five pounds.

Mr Mahmood at the Brick Lane Boutique, 137 Brick Lane, who began working as a machinist twenty-six years ago and started his own business twenty years ago, explained the root of the problem to me. “When I started here, I used to sell everything I made, but now the Chinese use artificial leather and in the chain stores people can buy one of these jackets for £15. So why are they going to come here and spend £100 for real leather?” he asked, his eyes glistening with emotion as he gestured around his shop which was more-than-half given over to t-shirts, with leather jackets consigned to a corner. Fortunately our conversation was interrupted by a customer who did want to spend £100 for a real leather jacket and so I left Mr Mahmood to it, thankful that his salesmanship had been given an opportunity to shine.

Bashir & Sons (London) Ltd at Bashir House is a towering landmark at 180 Brick Lane, where you can walk in to admire a vast stock of leather jackets in every permutation of design upon rails in a labyrinthine ground floor showroom. I was welcomed by the ebullient Mr Ahmed, one of the brothers in this family business which started forty-six years ago in Commercial St and moved to the current premises thirty-five years ago. “I started when I was sixteen,” he admitted to me in a nostalgic tone, “In those days, the customers just came and bought the stuff but now we have to sell it.” With outlets in Birmingham and elsewhere, this is an elaborate operation, manufacturing in Asia and distributing throughout Europe. “We’re not the biggest but the best,” Mr Ahmed assured me, demonstrating professional charm while boasting Dustin Hoffman and Lennox Lewis among his customers, “And we sell the largest selection of fancy sun glasses in London.”

Further down, at 168 Brick Lane, another Ahmed, proprietor of Oceanic Leather was the most frank of the leather sellers, in spite of his self-effacing demeanour. “A lot of people left or went bankrupt. We had a regular business and then one day it dried up.” he revealed with a melancholy frown, “I’ve suffered pain, but I rode out the worst part of it.” In his store, everything has been made in the workshop above, though there is nothing to indicate this to customers, just piles of pieces of high quality leather stacked up in the crowded space attesting to the distinction of the garments on display.

My final call was Rana Leather, 160 Brick Lane, where I discovered the proprietor Mr Rana and his beefy assistant trying to squash an impossibly large number of leather jackets into a tiny cardboard box. The beefy assistant held the box shut while Mr Rana wrapped it in tape and they succeeded in packing a curious irregularly-shaped parcel. Afterwards, Mr Rana wiped perspiration from his brow while explaining that he was one of three brothers who ran the business which started on Fashion St in 1975. This busy shop was filled with boxes of clothes in transit, as much a warehouse for the wholesale trade as a retail outlet, and it indicated that a certain volume of business was being done on the premises.

All but one of the leather shops I visited owned their buildings, which proved to be the key factor in their survival when others that paid the escalating rents had gone. I was fascinated to find that most were run by skilled men, experienced leatherworkers who offer the facility to have clothes and bags made to order. It was even more remarkable to learn that for a modest price you can buy a good quality jacket which has been made by hand in a workshop on Brick Lane. There may be only a few left, but my discovery was that these leather shops still have plenty going for them – if people only knew.

Abdul Bari, Truth Trading, founded his business by making clothes at home in 1978.

The grandchildren of M.Schulman, the kosher poulterer, gave this photo to Truth Trading, now operating from the same premises.

Mohammed Kamran’s uncle founded the business, Open Space, by selling leather jeans in Kensington Market in the seventies.

Mr Mahmood, Brick Lane Boutique, started as a machinist twenty-six years ago.

Mr Ahmed at Bashir Leather – “We are not the biggest but the best”

Ahmed, proprietor of Oceanic Leather.

Mr Rana of Rana Leather

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

Recent Paintings by Marc Gooderham

Lost Control Again (Hanbury St)

A year has passed since I came across the work of painter Marc Gooderham and here you see a selection of the new pictures he has created since then – of scenes that will be familiar to many readers. “My first year was just about getting going,” he admitted to me, “but now I’m in the flow of it and I’m in control of it. As time has gone by, I’ve thought more about composition and colour.”

“There’s so much more colour in my pictures because of the street artists, some of those works are so well painted, yet they’re giving it away – it keeps the streets really vibrant.” said Marc, modestly acknowledging the symbiotic relationship his paintings on canvas have with this most democratic of art forms.

Yet, speaking of his picture of Hanbury St, he says, “I saw that grey and the explosion of colour beside it, and I realised the grey had as much power as the colour.” Although they may appear superficially photorealistic, Marc subtly manipulates the elements he discovers to construct an intense personal vision which has a dreamlike quality. In each of his paintings, there is a dynamic contrast between the detailed rendering of architecture and the images applied by street artists, often amplified by an ethereal blue sky overhead.

It takes around a month for Marc to create a painting, building it up from architectural sketches and balancing the components. During the last year, as his paintings have got larger and his palette bolder, he has acquired a passionate following which means that once the pictures are the complete, the gallery takes them out of his hands. “It helps to have that routine of working on something and getting it finished within the month,” Marc confirmed, enjoying the momentum, “I like to paint them and there are people now that appreciate what I do, so that’s a good common ground.”

“Each of these paintings is about a discovery,” he confided to me, “I stumble upon them – I go out to explore the area and even though I am walking down familiar streets, I always find a new scene. There’s a lot to paint because the East End changes so quickly and my mission is to hunt out potential paintings, discovering more buildings that deserve to be painted.”

Marc Gooderham in Hanbury St yesterday.

The Split (Holywell Lane Car Park)

Wild and Free (Dalston Lane) – “I crept behind a car park, crawled through a fence and stumbled upon this, a large old house surrounded by scarecrows. It looked like a fantasy, a haunted house where the scarecrows were guarding the place.”

Blue Above the Wires (Mare St)

Smoke Stacks (Dalston Lane)

Nightfall on Whitepost Lane (Hackney Wick) – “I realised it looked as if it was glowing and so I went back during the day to find the right time when it looked like it was still alive, even though it was derelict.”

Fashion Street

Marc Gooderham in Toynbee St.

Marc Gooderham’s work is represented by Artisan Galleries

You may also like to read my original profile

So Long, Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange

After the proposal to demolish and redevelop the historic Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange was rejected unanimously twice by the members of Tower Hamlets Council, last night the Mayor of London, Boris Johnson, overruled them and gave the plan his blessing. Now, the sixty small businesses based there have to move out by the end of November to make way for the corporate office block that will take the place of the current building. Today I am republishing this account of my visit to the Exchange earlier this year.

Opening in 1929, when the volume of imported produce coming through the docks more than doubled in the ten years after the First World War, the mighty Fruit & Wool Exchange in Spitalfields was created to maintain London’s pre-eminence as a global distribution centre. The classical stone facade, closely resembling the design of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Christ Church nearby, established it as a temple dedicated to fresh produce as fruits that were once unfamiliar, and fruits that were out of season, became available for the first time to the British people.

After sixty years as a teeming warren of brokers and distributors, the building languished when the Fruit & Vegetable Market moved out from Spitalfields in 1991 and there were no wholesalers left to cross Brushfield St and supplement their supplies of British produce from the auctions at the Exchange. Since then, around sixty small businesses operated peaceably from the building which through its shabby grandeur reminded every visitor that it had once seen better days.

Yet it was only a matter of time before the notion of redevelopment arose, and when ambitious plans were revealed over a year ago for a huge new building to replace both the Exchange and the multi-storey car park behind it – filling two entire blocks – a sense of disquiet was generated in Spitalfields, especially among those who remembered the uneasy compromises entailed in the rebuilding of the Market.

Few have been convinced by the homogeneous box that was proposed to stand in place of the Exchange and many were disappointed when the creators of such mediocrity dismissed the current structure as of negligible architectural worth. In fact, the Commercial St end of the Exchange building closely matched the window structure and red brick of the eighteenth century houses in Fournier St, while the facade mirrored Christ Church itself. Since then, a revised proposal has been forthcoming which retains the Brushfield St frontage facing the Spitalfields Market but is far from being a design worthy to face Nicholas Hawksmoor’s masterpiece of English Baroque upon the opposite side of Commercial St.

And so, before it vanishes forever, I went over to take a look around and savour the past glories of the City of London Fruit & Wool Exchange for the last time.

Ascending from the grand entrance, a double staircase worthy of a ballroom in a liner or fancy hotel leads you up to the auction rooms. Built as the largest in the country, seating nearly nine hundred people, these magnificent panelled chambers were each the height of two storeys within the building. Fitted with microphones, which were an extraordinary innovation in 1929, possessing elaborate glass roofs that promised to simulate daylight – even on dark and foggy days – to best illuminate the fruit, they were served by high-speed hydraulic lifts to whisk samples of each consignment from the basement in the blink of an eye. Too bad that a recent fire, occurring since the redevelopment was announced, meant they could never be visited again. Now the entrances to the most significant spaces which define this edifice are sealed with tape and off-limits for ever, while charred parquet flooring evidences the flames that crept out under the door.

Instead, I had to satisfy myself with a stroll around the empty top floor through centrally-heated corridors maintained at a comfortable temperature ever since the offices were all vacated two years ago. Everywhere I could see evidence of the quality of this building, from the parquet floors which extend through each storey, to the well-detailed brass fixtures and high-quality Crittall window frames that were still in good order. Within the building, hidden light-wells permit glass-ceilings to be illuminated by daylight upon each storey. Peering into these spaces reveals the paradoxical nature of this edifice which presents ne0-classicism to the street but adopts a vigorous industrial-modernism within, employing vast geometric shaped concrete girders to support the roof spans of the auction rooms below and arranging rows of narrow metal windows in close grids that evoke Bauhaus design.

From the top, I descended through floors of long windowless corridors lined with doors, where an institutional atmosphere prevailed, hushing the speech of those stepping outside their offices as they enter these strange intermediary spaces that belong to no-one any more. My special curiosity was to explore the basement which served as a refuge for the residents of Spitalfields during the Blitz. It was here that Mickey Davies, an East End optician known as “Mickey the Midget,” became a popular hero through his work in improving the quality of this shelter. It had gained the reputation as the worst in London, but later acquired the name “Mickey’s Shelter” in acknowledgment of his good work. As a shelter marshall, Mickey witnessed the overcrowding and insalubrious conditions when ten thousand people turned up at this basement which had a maximum capacity of five thousand. He organised medical care and recruited volunteers to undertake cleaning rotas. And, thanks to his initiative, beds and toilets were installed, and even musical entertainment arranged.

The vast subterranean network of chambers has been empty for twenty years now – gloomy, neglected and scattered with piles of broken furniture. Although partitions have been fitted to create storage rooms – where, mysteriously, Rupert Murdoch recently installed his archive – the Commercial St end of the building remains open and forlorn, with concrete pillars adorned by graffiti. Fruit packers marked off batches of produce in pencil on the wall here, and amused themselves by writing their names and making clumsy doodles. In this lost basement, it is still possible to imagine the world of Mickey Davies, where thousands once slept upon the floor while the city burned outside.

From Brushfields St, the City of London Fruit & Wool Exchange appears implacable – yet I discovered it contains a significant part of the hidden history of Spitalfields that will shortly be erased, to leave just an empty facade.

The central staircase, worthy of a ballroom in a liner or grand hotel.

One of several light wells, lined with Crittall windows and permitting daylight to reach lower storeys.

Looking out towards Crispin St from the rear of The Gun.

Washing room in the basement.

As many as ten thousand people slept here every night while taking shelter from the London Blitz.

Nineteen forties graffiti portrait from the basement.

The telephone exchange.

State of art auction room in 1929, lit by a glass ceiling offering “artificial daylight” on foggy days.

Fruit & vegetable auction

An entrance to the Auction Hall, now sealed permanently after a recent fire.

The broken pediment at the top of this frontage mirrors Nicholas Hawksmoor’s design of Christ Church.

The Exchange in 1929. It is proposed that only this frontage be retained in the redevelopment.

View of Christ Church from the top floor.

You may also like to read about

At the Fruit & Wool Exchange, 1937

Mickey Davis at the Fruit & Wool Exchange

Fruit & Vegetable auction photograph courtesy of Stuart Kira

Other archive images courtesy of Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives

George Cruikshank’s Comic Alphabet

You might like to see other work by George Cruikshank

Jack Sheppard, Thief, Highwayman & Escapologist

The Bloody Romance of the Tower

Henry Mayhew’s Punch & Judy Man

and these other alphabets

Vivian Betts of Bishopsgate

Vivian & Toto outside The Primrose

You will not meet many who can boast the distinction of being brought up on the teeming thoroughfare of Bishopsgate but Vivian Betts is one who enjoyed that rare privilege, growing up above The Primrose on the corner of Primrose St where her parents were publicans from 1955 until 1974. Yet it was a different Bishopsgate from that of the present day with its soaring glass towers housing financial industries. In her childhood, Vivian knew a street lined with pubs and individual shops where the lamplighter came each night to light the gas lamps.

Living in a pub on the boundary of the City of London, Vivian discovered herself at a hub of human of activity. “I had the best of both worlds,” Vivian confessed to me, when she came up to Spitalfields on a rare visit yesterday, “I had the choice of City life or East End life, I could go either way. I had complete freedom and I was never in any danger. My father said to me if I ever had any trouble to go to a policeman. But all my friends wanted to come over to my place, because I lived in a pub!”

Vivian knew Bishopsgate before the Broadgate development swallowed up the entire block between Liverpool St and Primrose St. And as we walked together past the uniform architecture, she affectionately ticked off the order of the pubs that once stood there – The Kings Arms, The Raven and then The Primrose – with all the different premises in between. When we reached the windswept corner of Primrose St beneath the vast Broadgate Tower, Vivian gestured to the empty space where The Primrose once stood, now swallowed by road widening, and told me that she remembered the dray horses delivering the beer in barrels on carts from the Truman Brewery in Brick Lane.

In this landscape of concrete, glass and steel, configured as the environment of aggressive corporate endeavour, it was surreal yet heartening to hear Vivian speak and be reminded that human life once existed there on a modest domestic scale. Demolished finally in 1987, The Primrose had existed in Bishopsgate at least since 1839.

“My brother Michael was born in 1942, while Bill my father was away in the war, and Violet my mother got a job as a barmaid, and when he came back she said, ‘This is how I want to spend my life.’ Their first pub was The Alfred’s Head in Gold St, Stepney, in about 1946, and she told me she was washing the floor there in the morning and I was born in the afternoon. We left when I was three and all I remember of Stepney was walking over a bomb site to look at all the caterpillars.

In 1955, we moved into The Primrose at 229 Bishopsgate, directly opposite the Spitalfields market – you could look out of the window on the first floor and see the market. My first memory of Bishopsgate was lying in bed and listening to the piano player in the pub below. We had three pianos, one in the public bar, one in the first floor function room and one in our front room. On Sunday lunchtimes at The Primrose, it was so busy you could hardly see through the barroom for all the hats and smoke.

I used to go to Canon Barnet School in Commercial St and, from the age of seven, my dad would see me across Bishopsgate and I’d walk through the Spitalfields Market on my way to school where the traders would give me an apple and a banana – they all knew me because they used to come drinking in the pub. It was a completely Jewish school and, because no-one else lived in Bishopsgate, all my friends were over in Spitalfields, mostly in the Flower & Dean Buildings, so I spent a lot of time over there. And I used to come to Brick Lane to go the matinees at the cinema every Saturday. Itchy Park was our playground – in those days, the church was shut but we used to peek through the window and see hundreds of pigeons inside.

My dad opened one of the first carveries in a pub, where you could get fresh ham or turkey cut and made up into sandwiches and, in the upstairs room, my mum did sit-down lunches for three shillings – it was like school dinners, steak & kidney pudding and sausage & mash. She walked every day with her trolley to Dewhurst’s the butchers opposite Liverpool St, she got all her fruit and vegetables fresh from the Spitalfields Market, and she used to go to Petticoat Lane each week to buy fresh fish.

Every evening at 5pm, we had all the banks come in to play darts. On Mondays, it was the ladies of The Primrose darts team and on Wednesdays it was the men’s darts league. And, once each year, we organised the Presentation Dance at the York Hall. Every evening in the upstairs function room, we had the different Freemason’s lodges. Whenever I came out of my living room, I could always see them but I had to look away because it was part of my life that I wasn’t supposed to see. After I left school, I went to work for the Royal London Mutual Insurance Co. in Finsbury Sq – five minutes walk away – as a punchcard operator and, whenever it was anyone’s birthday, I’d say ‘Come on back to my mum’s pub and she’ll make us all sandwiches.’

Then in 1973, Truman’s wrote to my dad and gave him a year’s notice, they were turning the pub over to managers in April 1974, so we had to leave. But I had already booked my wedding for July at St Botolph’s in Bishopsgate, and I came back for that. Eighteen months later, in 1976, my mum and dad asked me and my husband to go into running a pub with them. It was The Alexandra Hotel in Southend, known as the “Top Alex” because there were two and ours was at the top of the hill.

Three months after we moved in, my dad died of cancer – so they gave it to my mum on a year’s widow’s lease but they said that if me and my husband proved we could run it, we could keep it. And we stayed until 1985. Then we had a murder and an attempted murder in which a man got stabbed, and my husband said, ‘It’s about time we moved.’ And that’s when we moved to our current pub, The Windmill at Hoo, near Rochester, twenty-eight years ago. We had a brass bell hanging behind the counter at The Primrose that came off a train in Liverpool St Station which we used to call time and we’ve taken it with us – all these years – but though we don’t call time any more, we still use it to ring in the New Year.

I’ve only ever had two Christmases not in a pub in my life, when you’re born to it you don’t know anything else.”

Vivian told me that she often gets customers from the East End in The Windmill and they always recognise her by her voice. “They say, ‘We know where you come from!'” she confided to me proudly.

The Primrose, 229 Bishopsgate, as Vivian knew it.

Toto sits on the heater in the panelled barroom at The Primrose.

Vivian at Canon Barnet School in Commercial St.

Bill and Vi Betts

“My first Freemason’s Lodge night when I was twelve or thirteen in 1965. My brother Michael with his wife Valerie on the right.”

Vivian stands outside The Primrose in this picture, looking east across Bishopsgate towards Spital Sq with Spitalfields market in the distance.

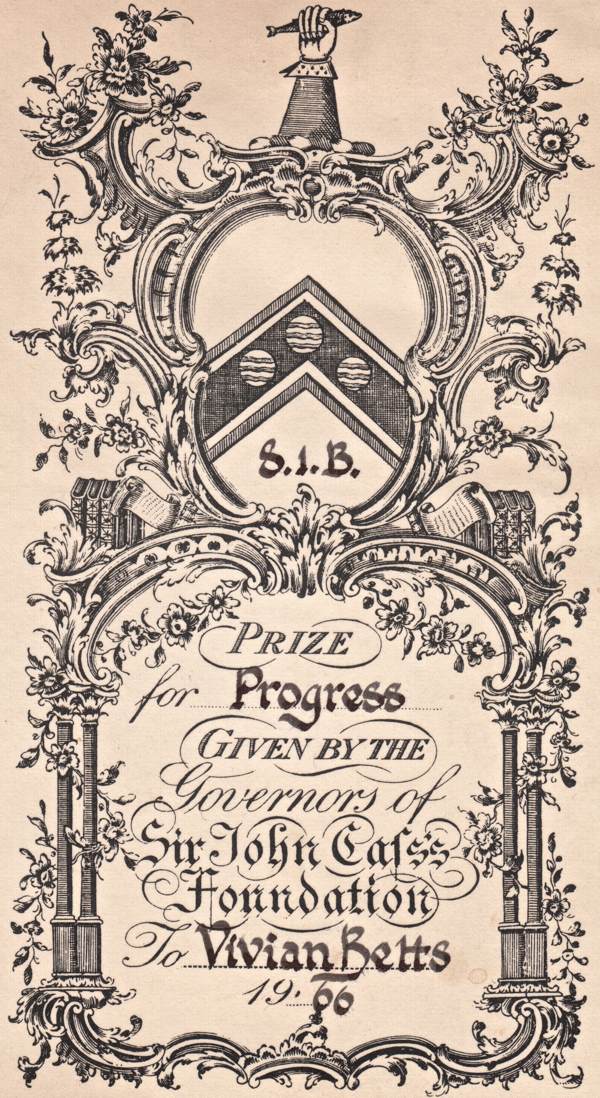

Vivian was awarded this certificate while a student at Sir John Cass School, Houndsditch.

Vivian on the railway bridge, looking west towards Finsbury Sq.

Vivian outside the door which served as the door to the pub and her own front door.

Vivian’s friends skylarking in Bishopsgate – “They always wanted to come over to my place because I lived above a pub!”

“When I was eight, we went abroad on holiday for the first time to Italy, we bought the tickets at the travel agents across the road and, after that, twelve or fourteen couples would come with us – my parents’ friends – and I was always the youngest there.”

Vivian prints out a policy at the Royal London Mutual Insurance Co. in Finsbury Sq.

“And what do you do?” – Vivian meets Prince Charles on a visit to Lloyd Register of Shipping in Fenchurch St.

“Harry the greengrocer and Tom the horse, they used to get their fruit & vegetables in the Spitalfields Market. My husband Dennis worked for this man when he was about twelve years of age, driving around the Isle of Dogs. He loved horses, and we’ve got a piece of land with our pub now and we’ve kept horses since 1980.”

Bill & Vi Betts in later years.

Vivian Betts at St Botolph’s Bishopsgate where she married her husband Dennis Campbell in 1974.

The Primrose in a former incarnation, photographed in 1912.

Bishopsgate with The Primrose halfway down on the right, photographed in 1912 by Charles Goss.

Bishopsgate today.

Archive photographs courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You might also like to take a look at these other Bishopsgate Stories

The Romance of Old Bishopsgate