The Flowers Of 2025

Anemones and paperwhites, 9th February

Each Sunday, if I can afford it and have the time, I visit Columbia Rd Market to buy a bunch of flowers, seeking what is in season and avoiding repeats, mostly. Here is the story of last year told in flowers. Looking back, I am reminded how much joy they brought me. Which are your favourites?

Hyacinths, 23rd February

Tulips, 2nd March

Parrot tulips, 31st March

Solomon’s seal, 4th May

Lilies of the valley, 11th May

Delphiniums, 1st June

Peonies and jasmine, 8th June

Achillea, eryngium and asters, 21st July

Dahlias, 17th August

Spiky dahlias, 31st August

Artichokes and chrysanthemums, 21st September

Dahlias, 26th October

Ranunculus, 9th November

Small chrysanthemums, 23rd November

Paperwhites, 11th December

The framed papercut is by Marion Elliot

You may also like to take a look at

So Long, Schrodinger

My beloved cat Schrodinger died suddenly on the night of Saturday 6th December. One moment he was happy and prancing, and the next he was gone. That evening he stretched out in front of the fire to warm himself, as was his custom, and then sat beside me on the sofa in companionship after dinner. When I went out for a walk around the neighbourhood before bed, Schrodinger followed me out of the house into the alley as he always did, settling there in the dark until my return.

When I came back, he was in the same place but slumped over and, as I approached, I could see his body was limp below the shoulders. He lifted his head and there was a brief moment of mutual recognition as I bent down, placing my hands upon him as I saw him choking and gasping for breath. Then his head twisted to one side and the life went out of him in a single exhalation. I ran my hand along his warm fur and supported the weight of his head, now that his neck was limp. The light was gone from his eyes. He was dead.

I wondered if I could had saved him if I had returned earlier, whether he had been holding out for my return. I was grateful that he did not die alone, that I did not return to discover him dead on the pavement.

I laid his head down gently and went into the house to fetch a blanket and carried him inside where I laid him on the carpet in disbelief at what had happened. I could detect no heartbeat or breath. His mouth leaked phlegm, although his body was uncorrupted, and I was expecting him to leap up into life again, but he did not. There was no curing him.

It should not have happened when he was so strong and full of life. Yet I recalled he had a seizure the day before when he threw up a large amount of phlegm. He recovered immediately, so I cleared it up and thought no more of it.

Last summer, the vet told me that Schrodinger had tooth decay and needed dental treatment but, since he had a weak heart, she would need to do further tests to see if it was possible for him to be anaesthetised and recover.

Yet there was never any diminution, Schrodinger was a bright spirit who always bounded at full strength. Maybe he slept more over the past year and there was a day recently when he slept from breakfast until dinner without awakening. I had assumed he had been out all night. But perhaps he grew old and got tired, and I had not noticed.

Schrodinger was a self-reliant creature who kept himself apart and carried the implacable mystery of his unknown origin. He was with me here in Spitalfields for seven years and lived two years before that at Shoreditch Church, where they had estimated he was two years old when he arrived from nowhere. By this reckoning he was eleven years old, though maybe he was older than anyone knew.

After making a phone call, I lifted his soft warm body into the large basket used to carry vegetables and cycled him over from Spitalfields to the veterinary surgery in Hoxton Square. It was late on Saturday night now and the streets were full with crowds celebrating loudly which jarred with Schrodinger’s final journey, gliding silently through the streets of Shoreditch and past the church where he came from.

When I told the duty vet about Schrodinger’s seizure the previous day and his weak heart, she explained that a build-up of phlegm on the lungs could be associated with a heart condition, so we concluded that he had died of heart failure. I left him there and cycled back to Spitalfields.

I thought of my father who fell asleep on the sofa after a day’s gardening at the age of seventy-nine, twenty-five years ago, and never woke up. I have known people suffer, dying slowly, and it has taught me that it is better to leave this life quickly as Schrodinger did.

But how I miss him. I miss him in the morning when I always gave him a dish of fresh water as the start to every day. I miss him waiting for me when I return to the house. I miss him jumping onto my lap whenever I sit down to write. I miss him in so many ways.

I missed him all through December. I missed him today and I shall miss him tomorrow. I shall miss him next year.

How I miss Schrodinger.

You may like to read my stories about Schrodinger

Schrodinger, Shoreditch Church Cat

Schrodinger’s First Winter in Spitalfields

Schrodinger’s First Year in Spitalfields

The Consolation of Schrodinger

The Gentle Author’s Writing Weekend

HOW TO WRITE A BLOG THAT PEOPLE WILL WANT TO READ – 7th & 8th FEBRUARY

Spend a weekend with me in an eighteenth century weaver’s house in Fournier St, enjoy delicious lunches, savour freshly baked cakes from historic recipes, discover the secrets of Spitalfields Life and learn how to write your own blog.

This course is suitable for writers of all levels of experience – from complete beginners to those who already have a blog and want to advance.

This course will examine the essential questions which need to be addressed if you wish to write a blog that people will want to read.

“Like those writers in fourteenth century Florence who discovered the sonnet but did not quite know what to do with it, we are presented with the new literary medium of the blog – which has quickly become omnipresent, with many millions writing online. For my own part, I respect this nascent literary form by seeking to explore its own unique qualities and potential.” – The Gentle Author

COURSE STRUCTURE

1. How to find a voice – When you write, who are you writing to and what is your relationship with the reader?

2. How to find a subject – Why is it necessary to write and what do you have to tell?

3. How to find the form – What is the ideal manifestation of your material and how can a good structure give you momentum?

4. The relationship of pictures and words – Which comes first, the pictures or the words? Creating a dynamic relationship between your text and images.

5. How to write a pen portrait – Drawing on The Gentle Author’s experience, different strategies in transforming a conversation into an effective written evocation of a personality.

6. What a blog can do – A consideration of how telling stories on the internet can affect the temporal world including publishing books, writing articles, creating guided walks, curating exhibitions and leading community campaigns.

SALIENT DETAILS

The course will be held at 5 Fournier St, Spitalfields on 7th & 8th February. The course runs from 10am-5pm on Saturday and 11am-5pm on Sunday.

Tea, coffee & cakes baked from eighteenth century recipes by the Townhouse, and lunches are included within the course fee of £350.

Email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com to book a place on the course.

Comments by students from courses tutored by The Gentle Author

“I highly recommend this creative, challenging and most inspiring course. The Gentle Author gave me the confidence to find my voice and just go for it!”

“Do join The Gentle Author on this Blogging Course in Spitalfields. It’s as much about learning/ appreciating Storytelling as Blogging. About developing how to write or talk to your readers in your own unique way. It’s also an opportunity to “test” your ideas in an encouraging and inspirational environment. Go and enjoy – I’d happily do it all again!”

“The Gentle Author’s writing course strikes the right balance between addressing the creative act of blogging and the practical tips needed to turn a concept into reality. During the course the participants are encouraged to share and develop their ideas in a safe yet stimulating environment. A great course for those who need that final (gentle) push!”

“I haven’t enjoyed a weekend so much for a long time. The disparate participants with different experiences and aspirations rapidly became a coherent group under The Gentle Author’s direction in a gorgeous house in Spitalfields. There was lots of encouragement, constructive criticism, laughter and very good lunches. With not a computer in sight, I found it really enjoyable to draft pieces of written work using pen and paper. Having gone with a very vague idea about what I might do I came away with a clear plan which I think will be achievable and worthwhile.”

“The Gentle Author is a master blogger and, happily for us, prepared to pass on skills. This “How to write a blog” course goes well beyond offering information about how to start blogging – it helps you to see the world in a different light, and inspires you to blog about it. You won’t find a better way to spend your time or money if you’re considering starting a blog.”

“I gladly traveled from the States to Spitalfields for the How to Write a Blog Course. The unique setting and quality of the Gentle Author’s own writing persuaded me and I was not disappointed. The weekend provided ample inspiration, like-minded fellowship, and practical steps to immediately launch a blog that one could be proud of. I’m so thankful to have attended.”

“I took part in The Gentle Author’s blogging course for a variety of reasons: I’ve followed Spitalfields Life for a long time now, and find it one of the most engaging blogs that I know; I also wanted to develop my own personal blog in a way that people will actually read, and that genuinely represents my own voice. The course was wonderful. Challenging, certainly, but I came away with new confidence that I can write in an engaging way, and to a self-imposed schedule. The setting in Fournier St was both lovely and sympathetic to the purpose of the course. A further unexpected pleasure was the variety of other bloggers who attended: each one had a very personal take on where they wanted their blogs to go, and brought with them an amazing range and depth of personal experience. “

“I found this bloggers course was a true revelation as it helped me find my own voice and gave me the courage to express my thoughts without restriction. As a result I launched my professional blog and improved my photography blog. I would highly recommend it.”

“An excellent and enjoyable weekend: informative, encouraging and challenging. The Gentle Author was generous throughout in sharing knowledge, ideas and experience and sensitively ensured we each felt equipped to start out. Thanks again for the weekend. I keep quoting you to myself.”

“My immediate impression was that I wasn’t going to feel intimidated – always a good sign on these occasions. The Gentle Author worked hard to help us to find our true voice, and the contributions from other students were useful too. Importantly, it didn’t feel like a ‘workshop’ and I left looking forward to writing my blog.”

“The Spitafields writing course was a wonderful experience all round. A truly creative teacher as informed and interesting as the blogs would suggest. An added bonus was the eclectic mix of eager students from all walks of life willing to share their passion and life stories. Bloomin’ marvellous grub too boot.”

“An entertaining and creative approach that reduces fears and expands thought”

“The weekend I spent taking your course in Spitalfields was a springboard one for me. I had identified writing a blog as something I could probably do – but actually doing it was something different! Your teaching methods were fascinating, and I learnt a lot about myself as well as gaining very constructive advice on how to write a blog. I lucked into a group of extremely interesting people in our workshop, and to be cocooned in the beautiful old Spitalfields house for a whole weekend, and plied with delicious food at lunchtime made for a weekend as enjoyable as it was satisfying. Your course made the difference between thinking about writing a blog, and actually writing it.”

“After blogging for three years, I attended The Gentle Author’s Blogging Course. What changed was my focus on specific topics, more pictures, more frequency, more fun. In the summer I wrote more than forty blogs, almost daily from my Tuscan villa on village life and I had brilliant feedback from my readers. And it was a fantastic weekend with a bunch of great people and yummy food.”

“An inspirational weekend, digging deep with lots of laughter and emotion, alongside practical insights and learning from across the group – and of course overall a delightfully gentle weekend.”

“The course was great fun and very informative, digging into the nuts and bolts of writing a blog. There was an encouraging and nurturing atmosphere that made me think that I too could learn to write a blog that people might want to read. – There’s a blurb, but of course what I really want to say is that my blog changed my life, without sounding like an idiot. The people that I met in the course were all interesting people, including yourself. So thanks for everything.”

“This is a very person-centred course. By the end of the weekend, everyone had developed their own ideas through a mix of exercises, conversation and one-to-one feedback. The beautiful Hugenot house and high-calibre food contributed to what was an inspiring and memorable weekend.”

“It was very intimate writing course that was based on the skills of writing. The Gentle Author was a superb teacher.”

“It was a surprising course that challenged and provoked the group in a beautiful supportive intimate way and I am so thankful for coming on it.”

“I did not enrol on the course because I had a blog in mind, but because I had bought TGA’s book, “Spitalfields Life”, very much admired the writing style and wanted to find out more and improve my own writing style. By the end of the course, I had a blog in mind, which was an unexpected bonus.”

“This course was what inspired me to dare to blog. Two years on, and blogging has changed the way I look at London.”

Night City By W S Graham

A few tickets left for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS on January 1st: CLICK HERE TO BOOK

Inspired by W S Graham’s poem, I took a walk through the nocturnal city, following in the poet’s footsteps with my camera to create this photoessay as an homage to Harold Burdekin

The Night City

Unmet at Euston in a dream

Of London under Turner’s steam

Misting the iron gantries, I

Found myself running away

From Scotland into the golden city.

I ran down Gray’s Inn Road and ran

Till I was under a black bridge.

This was me at nineteen

Late at night arriving between

The buildings of the City of London.

And then I (O I have fallen down)

Fell in my dream beside the Bank

Of England’s wall to bed, me

With my money belt of Northern ice.

I found Eliot and he said yes

And sprang into a Holmes cab.

Boswell passed me in the fog

Going to visit Whistler

Who was with John Donne who had just seen

Paul Potts shouting on Soho Green.

Midnight. I hear the moon

Light chiming on St. Paul’s.

The City is empty. Night

Watchmen are drinking their tea.

The Fire had burnt out.

The Plague’s pits had closed

And gone into literature.

Between the big buildings

I sat like a flea crouched

In the stopped works of a watch.

Unmet at Euston in a dream…

St Pancras Church

I ran down Gray’s Inn Road…

High Holborn

and ran till I was under a black bridge…

Boswell passed me in the fog…

Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese

I hear the moonlight chiming on St. Paul’s…

Fell in my dream beside the Bank of England’s wall to bed…

Whalebone Court

…just seen Paul Potts shouting on Soho Green…

Poem copyright © The Estate of W S Graham

You may also like to take a look at

Some Christmas Baubles

Simply add discount code ‘FIFTY’ at checkout

I do not know when my grandmother bought this glass decoration and I cannot ask her because she died more than twenty years ago. All I can do is hang it on my tree and admire it gleaming amongst the deep green boughs, along with all the others that were once hers, or were bought by my parents, or that I have acquired myself, which together form the collection I bring out each year – accepting that not knowing or no longer remembering their origin is part of their charm.

Although I have many that are more elaborate, I especially admire this golden one for its simplicity of form and I like to think its ridged profile derives from the nineteen thirties when my mother was a child, because my grandmother took the art of Christmas decoration very seriously. She would be standing beech leaves in water laced with glycerine in October, pressing them under the carpet in November and then in December arranging the preserved leaves in copper jugs with teazles sprayed gold and branches of larch, as one of many contrivances that she pursued each year to celebrate the season in fastidious style.

Given the fragility of these glass ornaments, it is extraordinary that this particular decoration has survived, since every year there are a few casualties resulting in silvery shards among the needles under the tree. Recognising that a Christmas tree is a tremendous source of amusement for a cat – making great sport out of knocking the baubles to the ground and kicking them around like footballs – I hang the most cherished decorations upon the higher branches. Yet since it is in the natural course of things that some get broken every year and, as I should not wish to inhibit the curiosity of children wishing to handle them, I always buy a couple more each Christmas to preserve the equilibrium of my collection.

Everlasting baubles are available – they do not smash, they bounce – but this shatterproof technological advance entirely lacks the poetry of these fragile beauties that can survive for generations as vessels of emotional memory and then be lost in a moment. In widespread recognition of this essential frailty of existence, there has been a welcome revival of glass ornaments in recent years.

They owe their origins to the glassblowers of the Thuringian Forest on the border of Germany and the Czech Republic where, in Lauscha, glass beads, drinking glasses, flasks, bowls and even glass eyes were manufactured since the twelfth century. The town is favoured to lie in a wooded river valley, providing both the sand and timber required for making glass and in 1847 Hans Greiner – a descendant of his namesake Hans Greiner who set up the glassworks in 1597 with Christoph Muller – began producing ornaments by blowing glass into wooden moulds. The inside of these ornaments was at first coloured to appear silvery with mercury or lead and then later by using a compound of silver nitrate and sugar water. In 1863, when a gas supply became available to the town, glass could be blown thinner without bursting and by the eighteen seventies the factory at Lauscha was exporting tree ornaments throughout Europe and America, signing a deal with F.W.Woolworth in the eighteen eighties, after he discovered them on a trip to Germany.

Bauble is a byword for the inconsequential, so I do not quite know why these small glass decorations inspire so much passion in me, keeping their romance even as other illusions have dissolved. Maybe it is because I collect images that resonate personally? As well as Father Christmas and Snowmen, I have the Sun, Moon and Stars, Clocks and even a Demon to create a shining poem about time, mortality and joy upon my Christmas tree. I cannot resist the allure of these exquisite glass sculptures in old-fashioned designs glinting at dusk amongst the dark needles of fir, because they still retain the power to evoke the rich unassailable magic of Christmas for me.

This pierrot dates from the nineteen eighties

Three of my grandmother’s decorations. The basket on the left has a piece of florists’ wire that she placed there in the nineteen fifties

This snowman is one of the oldest of my grandmother’s collection

Bought in the nineteen eighties, but from a much older mould

Baubles enhanced with painted stripes and glitter

The moon, sun and stars were acquired from a shop in Greenwich Avenue on my first visit to New York in 1990, amazingly they survived the flight home intact

These two from my grandmother’s collection make a fine contrast of colour

Even Christmas has its dark side, this demon usually hangs at the back of the tree

It is always going to be nine o’clock on Christmas Eve

Three new decorations purchased at Columbia Rd

A stash of glittering beauties, stored like rare eggs in cardboard trays

Russian cosmonauts from the sixties that I bought in Spitalfields Market

My first bicycle, that I found under the tree one Christmas and still keep in my attic

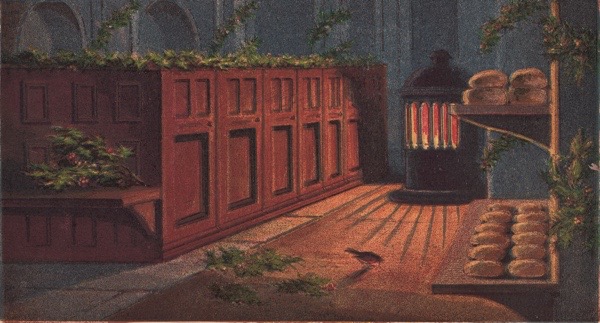

The Robin’s Christmas

Simply add discount code ‘FIFTY’ at checkout

This extract is from ‘Aunt Louisa’s Keepsake’ published by Frederick Warne which was given to me by Libby Hall. The copy is inscribed ‘Christmas 1896’ inside the front cover.

‘Twas Christmas-time, a dreary night,

The snow fell thick and fast,

And o’er the country swept the wind,

A keen and wintry blast.

The Robin early went to bed,

Puffed up just like a ball,

He slept all night on one small leg,

Yet managed not to fall.

No food had touched his beak,

And not a chance had he

Of ever touching food again,

As far as he could see.

The stove had not burnt very low,

But still was warm and bright,

And round the spot whereon it stood,

Threw forth a cheerful light.

Now Robin from a corner hopped,

Within the fire’s light.

Shivering and cold, it was to him

A most enchanting sight.

But he is almost starved, poor bird!

Food he must have, or die,

Unless it seems, alas! for that

Within these walls to try.

Perhaps ‘t is thought by those who read

To doubtful to be true,

That just when they were wanted so

Some hand should bread crumbs strew.

But this is how it came to pass,

An ancient dame had said,

Her legacy unto the poor

Should all be spent on bread.

Enough there was for quite a feast,

Robin was glad to find.

The hungry fellow ate them all,

Nor left one crumb behind.

You may also like to take a look at

The Ghosts Of Old London

Simply add discount code ‘FIFTY’ at checkout

Click to enlarge this photograph

To dispel my disappointment that I cannot rent that Room to Let in Old Aldgate, I find myself returning to scrutinise the collection of pictures taken by the Society for Photographing the Relics of Old London held in the archive at the Bishopsgate Institute. It gives me great pleasure to look closely and see the loaves of bread in the window and read the playbills on the wall in this photograph of a shop in Macclesfield St in 1883. The slow exposures of these photographs included fine detail of inanimate objects, just as they also tended to exclude people who were at work and on the move but, in spite of this, the more I examine these pictures the more inhabited they become.

On the right of this photograph, you see a woman and a boy standing on the step. She has adopted a sprightly pose of self-presentation with a jaunty hand upon the hip, while he looks hunched and ill at ease. But look again, another woman is partially visible, standing in the shop doorway. She has chosen not to be portrayed in the photograph, yet she is also present. Look a third time – click on the photograph above to enlarge it – and you will see a man’s face in the window. He has chosen not to be portrayed in the photograph either, instead he is looking out at the photograph being taken. He is looking at the photographer. He is looking at us, returning our gaze. Like the face at the window pane in “The Turn of the Screw,” he challenges us with his visage. Unlike the boy and the woman on the right, he has not presented himself to the photographer’s lens, he has retained his presence and his power. Although I shall never know who he is, or his relationship to the woman in the doorway, or the nature of their presumed conversation, yet I cannot look at this picture now without seeing him as the central focus of the photograph. He haunts me. He is one of the ghosts of old London.

It is the time of year when I think of ghosts, when shadows linger in old houses and a silent enchantment reigns over the empty streets. Let me be clear, I am not speaking of supernatural agency, I am speaking of the presence of those who are gone. At Christmas, I always remember those who are absent this year, and I put up all the cards previously sent by my mother and father, and other loved ones, in fond remembrance. Similarly, in the world around me, I recall the indicators of those who were here before me, the worn step at the entrance to the former night shelter in Crispin St and the eighteenth century graffiti at the entrance to St Paul’s Cathedral, to give but two examples. And these photographs also provide endless plangent details for contemplation, such as the broken windows and the shabby clothing strung up to dry at the Oxford Arms, both significant indicators of a certain way of life.

To me, these fascinating photographs are doubly haunted. The spaces are haunted by the people who created these environments in the course of their lives, culminating in buildings in which the very fabric evokes the presence of their inhabitants, because many are structures worn out with usage. And equally, the photographs are haunted by the anonymous Londoners who are visible in them, even if their images were incidental to the purpose of these photographs as an architectural record.

The pictures that capture people absorbed in the moment touch me most – like the porter resting his basket at the corner of Friday St – because there is a compelling poetry to these inconsequential glimpses of another age, preserved here for eternity, especially when the buildings themselves have been demolished over a century ago. These fleeting figures, many barely in focus, are the true ghosts of old London and if we can listen, and study the details of their world, they bear authentic witness to our past.

Two girls lurk in the yard behind this old house in the Palace Yard, Lambeth.

A woman turns the corner into Wych St.

A girl watches from a balcony at the Oxford Arms while boys stand in the shadow below.

At the Oxford Arms, 1875.

At the entrance to the Oxford Arms – the Society for Photographing the Relics of Old London was set up to save the Oxford Arms, yet it failed in the endeavour, preserving only this photographic record.

A relaxed gathering in Drury Lane.

A man turns to look back in Drury Lane, 1876.

At the back of St Bartholomew’s, Smithfield, 1877.

In Gray’s Inn Lane.

A man peers from the window of a chemists’ at the corner of Lower James St and Brewer St.

A lone policeman on duty in High Holborn, 1878.

A gentleman in Barnard’s Inn.

At White Hart Inn yard.

At Queen’s Inn yard.

A woman lingers in front of the butcher in Borough High St, Southwark.

In Aldgate.

A porter puts down his basket in the street at the corner of Cheapside and Friday St.

In Fleet St.

The Old Bell, Holborn

At the corner of Fore St and Milton St.

Doorways on Lawrence Pountney Hill.

A conversation at the entrance to Inner Temple, Fleet St.

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You can see more pictures from the Society for Photographing the Relics of Old London here In Search of Relics of Old London