Just Another Day With John Claridge

Cobb St, Spitalfields 1966

One morning in 1966, photographer John Claridge met these four men working in Cobb St, Spitalfields. “They were bloody silly,” recalled John fondly half a century later, “and there’s not enough of that in this world.” It was John’s way of introducing this set of pictures to me, published here for the first time, which he entitles“Just Another Day.”

“They were good people – full of fun – and this picture was nice to take, it has a warmth to it.” he added, upon contemplation of the image. And, if there is a common quality among these pictures, it is an open-hearted delight in the quotidian, or as John puts it –“The daily things that people do, going to work, stopping at the corner, visiting the shops.”

Where others might find only the mundane, John sees the poetry of the human condition. There may be endless sleet in Spitalfields, freezing fog in Victoria Park, and the passengers are eternally falling asleep on the early train out of Upton Park, yet John always reveals the joy and the humanity of his subjects. A generous spirit informs his photographs.

“Some of these pictures are of life drifting by,” John informed me, “because there are gentler ways of seeing the world than the obvious.”

Cup of tea, Spitalfields 1966.

Kosher butchers, Bethnal Green 1962 – “It wasn’t very big and it did have a certain smell to it.”

The cap, Spitalfields 1982 – “I love the things you don’t know as well as the things that are explained.”

Four men, Spitalfields 1982 – “You could create your own story with that.”

The baker at Rinkoffs, Vallance Rd, Bethnal Green 1967 – “Having a cup of tea and enjoying a breath of fresh air as the light’s coming up.”

Rinkoffs, Bethnal Green 1967

Breaker’s yard, E16 1975 – “I was talking to her dad and she just wandered off and got in the car.”

Feeding the birds in Victoria Park, E3 1962 – “there was ice on the lake.”

Passing the graveyard, 1970s

Bridge repair, E3 1960s

The crane, E16 1975 – “I printed this photo for the first time last week.”

SOS motors, Spitalfields 1982

Sewer Bank, Plaistow 1960s – “Where the kids used to go on their bikes and I’d take my scrambler. The craters were fantastic, it was a different kind of playground.”

In Plaistow, 1961 – “Just down the road from where I lived. It certainly has a lot of charm to it, look at how little traffic there is. That could be my dad on the bike, coming back from the docks.”

Station stairs, Upton Park 1963 – “Sometimes I met my mum here after school, when she was coming back from Bow where she worked as machinist making shirts.”

Station entrance, Upton Park 1963 – “I like stations, it’s that feeling you get of arriving on a film set.”

Leaving Plaistow early morning in winter, E13 1963 – “I had a motorbike but I liked going on the tube if the traffic was bad.”

The shed, Plaistow 1969 – “This was at the top of the street where I lived. He used to go round with that barrow and pick things up, and sell bits and pieces in that shed. A very nice man and a gentleman.”

End of the day, Spitalfields 1963.

Photographs copyright © John Claridge

You may also like to take a look at

Along the Thames with John Claridge

At the Salvation Army with John Claridge

A Few Diversions by John Claridge

Signs, Posters, Typography & Graphics

Views from a Dinghy by John Claridge

In Another World with John Claridge

A Few Pints with John Claridge

Some East End Portraits by John Claridge

When Rupert Blanchard Met Bruno Besagni

Rupert Blanchard & Bruno Besagni

Ten years ago, Rupert Blanchard found a beautiful plaster horse in the Coppermill Market in Cheshire St one Sunday morning. At once, the quality of the design and the expertise of the painting caught his eye. Rupert was further intrigued by the initials BB upon the reverse which he had seen before upon other plaster casts for sale in markets back in Swindon where he grew up. The seller of the horse was an old man who had received it new as a wedding present more than forty years ago and now he was divesting himself of his possessions.

It was the first of these horses that Rupert acquired and, in the intervening years, he collected more and more at the car boot sales and fairs where he finds the things that inspire his own work as a furniture maker and designer. So fond of these horses was Rupert that he displayed them proudly alongside his own work at exhibitions.

Imagine his surprise when he read my profile of Italian reproduction artist Bruno Besagni in these pages recently and recognised these plaster horses in their unpainted state in a photo of Bruno at his factory at Stratford, where he made casts in the sixties and seventies. Once I learnt of this discovery, I realised that it was my duty to introduce Rupert and Bruno, the young talent and the old master.

Rupert brought along the original horse that he found in Cheshire St which he keeps as a talisman. He carried it swathed in cloth and clutched it close like a baby, as we walked through the crowded streets of the Angel towards the terrace in the quiet Georgian square where Bruno has lived with his wife Olive for more than fifty years.

“Yes, it’s definitely one of mine!” declared Bruno, breaking into a radiant smile of recognition, as Rupert unwrapped the horse upon the living room carpet, “I painted this one.” A self-confessed Italian Cockney, Bruno trained as a painter at the Giovanni Pagliai factory in Great Sutton St in the nineteen forties, when Clerkenwell was still the centre of the Italian community and known as Little Italy. Pagliai came from Lucca, the centre of religious statuary making in Italy, and the training that Bruno received educated him in this age-old tradition. For centuries, plaster cast sellers from Lucca had plied their trade upon the streets of London selling ornaments in popular designs for the mass market.

Yet Bruno’s passion for his art let him down in business because he could never sell his works for a price that justified the time he spent perfecting them – while rivals produced cruder versions that sold equally well, sometimes pirating Bruno’s own designs. “I was doing all these lovely jobs,” said Bruno gesturing affectionately to his horse, “and I never made any money.”

Such was Bruno’s talent that he made the replica of the statue of St Mary of Mount Carmel that is carried in the Italian Parade in Clerkenwell each year and he has done all the repairs to the statues of saints in the Italian church over the years, replacing their fingers when they got broken off and keeping them all in good order. Today, plaster casts are no longer made as ornaments, resin has replaced plaster, which is now only used for internal architectural mouldings – making Bruno one of the very last to carry the particular skills of making and painting plaster figures.

The popularity of Bruno’s horses and his other designs allowed him set up his own factory in Stratford, only to come up against the very end of the culture. Crudely produced fairground imitations degraded the notion of cast ornamental sculpture. “It went down the tubes, I couldn’t sell one article once they went out of fashion,” confessed Bruno, “It was my dream, but one day we couldn’t sell horses any more.”

“I packed up the statues and went and did artistic work, ornamental plasterwork in hotels,” he recalled, looking back in regret,“but my love was in the statues.” Apart from a lamp in the corner of his sitting room and a mould for the bust of Shakespeare in the shed, Bruno forgot about his statues until last week when Rupert Blanchard appeared with the horse.

It was an extraordinary moment of mutual recognition. Rupert, a designer at the beginning of his career, was full of wonder to meet the legendary “BB” whose initials he had seen on innumerable plaster casts. Equally, Bruno was amazed in his eighty-seventh year to learn that someone with an informed eye had picked out his work from so long ago and understood the quality of it. It was evidence that Bruno was an artist in his chosen medium and the horse was a testament to his achievement in this devalued area of design.

“I didn’t do bad work did I?” said Bruno, thinking out loud as we made our farewells, “It was lovely to see that again, I’m so pleased I found someone who appreciates my work.”

The first lamp of Bruno’s that Rupert found ten years ago in Cheshire St.

Bruno’s factory in Stratford where he made the casts.

Two horses by Bruno from Rupert’s collection.

Two horses by Bruno from Rupert’s collection.

Polly Benford restores the paintwork on one of Bruno’s horses.

A Bruno Besagni horse lamp displayed alongside Rupert Blanchard’s furniture at Midcentury Modern.

London street seller of plaster casts from Lucca drawn by John Thomas Smith in 1816.

Studio photographs copyright © Rupert Blanchard

John Thomas Smith image courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to read my original profiles

Bruno Besagni, Reproduction Artist

and his wife

Olive Besagni, Assistant Film Editor

and

So Long, General Woodwork Supplies

Today, the proprietors of General Woodwork Supplies in Stoke Newington High St hand over the keys of the premises where they have been trading since 1946 to the new owner of the building, and thereby ends the story of a family business that began in Curtain Rd in Shoreditch with General Furniture Trade Supplies in 1896. Already, the handymen of the East End are grieving the loss of this celebrated hardware shop and builders’ merchant that stocked everything, where they cut timber to size, and where you could always get advice and even instructions on how to do it yourself.

General Woodwork Supplies was one of London’s great hardware shops, a temple to the art of do-it-yourself, with innumerable drawers stretching up to the ceiling that contained every possible fixture and fitting. The organisation of the interior had evolved over more than half a century through function and requirement, with two long counters facing you as you walked in the door and a capacious wood store leading off to the right. Every surface and corner was encrusted with a display of household paraphernalia and there were a myriad useful things hanging from above. And, like barmen in a Wild West saloon, the staff welcomed everyone with an understated swagger at General Woodwork Supplies, leaning forward across the counter to engage in banter.

From my own experience, I can vouch this was an invaluable place because they did not expect you to be an expert, showing indulgence while you explained what you needed to do in your own words. And invariably, they always supplied what you needed to do it where other shops failed.

Recognising that an endeavour of such admirable longevity and popular repute must not be allowed to slip un-noticed into history, I went up to Stoke Newington in the final days of General Woodwork Supplies and spoke with Jeff Bentley who has been running the business alongside his two brother-in-laws Michael and David Cohen in recent decades. Meanwhile, photographer Simon Mooney slipped in behind the counter to create his own elegy in pictures.

“My father-in-law Harry started General Woodwork Supplies in 1946. His father Mark Cohen was a master carpenter, he had a business in Curtain Rd – General Furniture Trade Supplies – which the old man established in 1896, supplying the furniture trade in Shoreditch. By the twenties, they were making cinema seats and supplying all the metalwork and brassware to go with them. But in World War II they took a direct hit, all they could do was salvage the stock and put it in storage. And Mark retired then. My father-in-law was in the fire service and since he had a lot of spare time, he used to make toys during the day. Then, after the war, Harry had a workshop with his brother Morry, doing distressed furniture and making it look antique for the Americans. Yet Harry wanted to open a shop, he was in this late twenties and his old man was in his sixties, and meanwhile Morry went off the work as a cabinet maker, he was more skilled.

Harry started off at 120 Stoke Newington Rd for a short time, selling ironwork and brassware, until the building was compulsorily purchased by the council to build flats. He and his wife Dora had three little children by then – David born in 1937, Rita born in 1941 and Michael born in 1946 – and they started off with very small beginnings. He managed to obtain a licence from the Board of Trade to deal in timber, and because of his connections in the business he was able to obtain hardwood, but it was a struggle and they really worked hard.

He rented 78 Stoke Newington High St and he sold some of the salvaged stock from Curtain Rd, he did whatever he could to earn a crust. He made things. He would make box pelmets to order and go into people’s homes to fit them, and that was the mainstay of his trade. His son David went into the airforce for a couple of years before joining the family business. Then, David had an accident and cut a finger off, so young Michael got a dispensation to leave school and work with him at fourteen years old. They employed people and grew the business, and the shop next door became available and they expanded into it. In 1947, they bought the freehold in number 78 and then the freehold of 80 became available too and later 76, and they bought both. During this time, Harry had the foresight to take any job. He said, ‘I can do it,’ knowing he did not have the equipment, but over the years he expanded and bought machinery. It was the cart before the horse.

People started to do work themselves in the mid-fifties. Labour was still cheap but in sixties when it became expensive everyone began to turn their hands to doing things themselves. And, by the late sixties and early seventies, everything went ‘contemporary’ with clean lines and people wanting to get rid of mouldings and features. Rather than replacing panelled doors, we would cut a piece of hardboard to size and they would pin it onto the door and create a modern flush door. They would cut off newel posts and box in banisters to hide the spindles, and this continued throughout the seventies. We got a good reputation for quality things people wanted, we could produce the pieces of wood to size and they could do it themselves. Harry was into specialist hardwoods and we could make skirting and mouldings to order. We started a mail order business and sold timber all over the world. The machines were working all hours of the day!

After property in Islington got too expensive, we got the overflow down here. They were gentrifying, and what we found was that these large houses, which after the war had been converted into flats, were being returned to single houses and we started making the mouldings to fit back to restore them to what it was previously.

I joined the business in 1968. I was a television engineer and I worked in retail selling televisions, and I had been doing that for ten years. When I got married, I was invited to join the family firm. There wasn’t actually a gun put to my head, but it seemed the thing to do and they were welcoming. I had no formal woodwork training apart from what I learnt at school and the rest I picked up as I went along. My father-in-law was the boss and, as he got older, Harry decided that his youngest, Michael, was most adept at business and asked him to handle the day-to-day running, while David leaned towards machinery and he took care of that side of things. I fitted in doing what I was told, most of my time was spent with customers. But everybody knew everything, so we could all cover for each other.

Harry died in February 1991, and he came into the shop regularly until January of that year. All this time, his wife Dora – who is now ninety-nine years old – was in charge of the book-keeping side of the business. My wife gave up her work as a legal secretary when our first child was born, but when our second was two or three, she decided to go and help her mum do the book work. Then Michael got married and, after their little girl was born, his wife joined the other two women doing the books between the three of them, and that’s how things were done.

Now, David is seventy-five, I am seventy-three and Michael is sixty-seven, and the thought of the business going into other hands without us is something we would not want. I have a house that’s been neglected for fifteen years and needs some tender loving care, and I shall try to do it myself. “

Michael Cohen

David Cohen

Jeff Bentley

“Stokey will bloody miss you, it will go down hill!” – “What will we do without you?”

“Good Luck to the three of U” – “Worst news I heard all month! No it can’t be true” – “Thankyou for the help” – “So sad” – ” You will be missed!”

Photographs copyright © Simon Mooney

You might also like to read about these other hardware stores which remain open

London Calling

Click to enlarge Bob & Roberta Smith’s painting

Running in the gallery at Eleven Spitalfields until 26th October, London Calling is a joint exhibition by two artists who are husband and wife, Jessica Voorsanger and the artist known as Bob & Roberta Smith. Both have lived in the East End for the past twenty-two years, since they were married, but they came very different paths to get here and the contrast between their work in this exhibition reveals their complementary relationships to London.

New Yorker, Jessica Voorsanger, first came to London when she was five and ate banana ice cream every day, but what she remembers most vividly was going to Madame Tussauds and talking to an old lady on a bench who turned out to be a waxwork. This same mixture of affection for London landmarks, coloured with a fascination for celebrity and underscored by surrealism, informs her intricate collages. Taking pages from an old tourist souvenir book entitled ‘This is London,’ Jessica has superimposed the faces of famous people upon familiar scenes, creating a bizarre effect worthy of Max Ernst. In Jessica’s work, the mythic landscapes of Central London become the location of collective dreaming, alluring and mysterious.

Bob & Roberta Smith‘s painting above is also inspired by a personal memory of London, that of coming to the East End for an Anti-Nazi march in the late seventies, and of his father recalling the Battle of Cable St. “The East End is the most vibrant, fought-over piece of London with people always coming and going. I grew up in Wandsworth and there was none of that life in West London. I find it very exciting here.” Bob admitted to me, tipping his cap to express his enthusiasm. For the last seventeen years, Bob has taught at the Cass School of Art in Aldgate, cycling along the Bow Rd from Leytonstone where he and Jessica live. And it is this experience which informs his desire to bring back the trams, a pipe dream turned ultimatum graven in his trademark skew-whiff lettering, lovingly painted with ‘One Shot’ signwriting enamel in exuberant colours upon some scruffy old boards picked up in a skip.

“I want to re-invent Whitechapel by bringing back the trams. The tram is such a great piece of design and it was green, and the Bow Rd is living hell. My dream would be to see it lined predominantly with windmills, lavender for the bees, poplar trees and cycle tracks, and there’s no reason why it can’t happen.” Bob assured me, exchanging a complicit smile with Jessica. And I was persuaded.

Rebuild the Bow Rd tram.

British Museum

Imagine the Mile End of the future.

Guildhall.

The replacement for the Routemaster bus.

Belgrave Sq.

The re-opening of the Whitechapel Gallery.

Westminster.

Piccadilly Circus.

Paintings copyright © Bob & Roberta Smith

Collages copyright © Jessica Voorsanger

LONDON CALLING runs until 26th October, more information from Eleven Spitalfields.

MAKE YOUR OWN DAMN ART, a film about Bob & Roberta Smith is being shown at the Curzon Soho this Saturday 22nd September.

Jessica Voorsanger is contributing the imagery for Chapter 22 in MOBY DICK – THE BIG READ, an online audio version of Moby Dick.

Jessica Voorsanger and Bob & Roberta Smith will be leading a walking tour from Eleven Spitalfields on Sunday 14th October.

Neville Turner of Elder St

This is Neville Turner sitting on the step of number seven Elder St, just as he used to when he was growing up in this house in the nineteen forties and fifties.

When Neville lived here, the landlords did no maintenance and the building was dilapidated. But Neville’s Uncle Arthur wallpapered the living room with attractive wisteria wallpaper, which became the background to the happy family life they all enjoyed, in the midst of the close-knit community in Elder St during the war and afterwards. Subsequently, the same wisteria wallpaper appeared as a symbol of decay, hanging off the wall, in photographs taken to illustrate the dereliction of Elder St when members of the Spitalfields Trust squatted it to save the eighteenth century houses from demolition.

It was only when an artist appeared – one Sunday morning in Neville’s childhood – sketching the pair of weaver’s houses at number five and seven, that Neville became aware that he was growing up in a dwelling of historic importance. Yet to this day, Neville protests he carries no sentiment about old houses. “This affection for the Dickensian past is no substitute for hot and cold running water,” he admitted to me frankly, explaining that the family had to go the bathhouse in Goulston St each week when he lived in Elder St.

However, in spite of his declaration, it soon became apparent that this building retains a deep personal significance for Neville on account of the emotional history it contains, as he revealed to me when he returned to Spitalfields this week.

“My parents moved from Lambeth into number seven Elder St in 1931 and lived there until they were rehoused in 1974. The roof leaked and the landlords let these houses fall into disrepair, I think they wanted the plots for redevelopment. But then, after my parents were rehoused in Bethnal Green, the Spitalfields Trust took them over in 1977.

I was born in 1939 just before the war began and my mother called me Neville after Neville Chamberlain, who she saw as the bringer of peace. I got a lot of stick for that at school. I had two elder brothers, Terry born in 1932 and Douglas born in 1936. My father was a firefighter and consequently we saw a lot of him. I felt quite well off, I never felt deprived. In the house, there was a total of six rooms plus a basement and an outside basement, and we lived in four rooms on the ground floor and on the first floor, and there was a docker and his wife who lived up on the top floor.

My earliest memory is of the basements of Elder St being reinforced as air raid shelters in case the buildings collapsed – and of going down there when the sirens sounded. Even people passing in the street took shelter there. Pedlars and knife-grinders, they would bang on the door and come on down to the basement. That was normal, we were all part and parcel of the same lot. I recall the searchlights, I found it interesting and I wondered what all the excitement was about. War seemed quite mad to me and, when it ended, I remember the street party with bonfires at each end of the street and everybody overjoyed, but I couldn’t understand why they were all so happy. None of the houses in Elder St were damaged.

We used to play out in the street, games like Hopscotch and Tin Can Copper. All the houses had a door where you could go up onto the roof and it was normal for people in the terrace to walk along the roof, visiting each other. You’d be sitting in your living room and there’d be a knock on the window from above, and it was your neighbours coming down the stairs. As children, we used to go wandering in the City of London, and I remember seeing typists typing and thinking that they did not actually make anything and wondering, ‘Who makes the cornflakes?’ Across Commercial St, it was all manufacturing, clothing, leather and some shoemaking – quite a contrast.

After the war, my father worked as a bookie’s runner in the Spitalfields Market, where the porters and traders were keen gamblers, and he operated from the Starting Price Office in Brushfield St. He never got up before ten but he worked late. They were not allowed to function legally and the police would often take them in for a charge – the betting slips had to be hidden if the police came round. At some parts of the year, we were well off but other parts were call the ‘Kipper Season’ which was when the horse-racing stopped and the show-jumping began, then we had very little. I knew this because my pocket money vanished.

I joined the Vallance Youth Club in Chicksand St run by Mickey Davis. He was only four foot tall but he was quite a strong character. He was attacked a few times in the street on account of being short and a few of us used to call up to his flat above the Fruit & Wool Exchange, so that he could walk with us to the club, but then he got ill and died. Tom Darby and Ashel Collis took over running the club, one was a silversmith and the other was a passer in the tailoring trade. We did boxing, table tennis and football, and they took us camping to Abridge in Essex. We got a bus all the way there and it only cost sixpence.

I moved on to the Brady Club in Hanbury St – it changed my outlook on life. They had a music society, a chess society, a drama society and we used to go to stay at Skeate House in Surrey at weekends. If you signed up to pay five shillings a week, you could go on a trip to Switzerland for £15. Yogi Mayer was the club captain. He called me in and said, ‘This is a private chat. We are asking every boy – If you can’t manage the £15, we will make up the shortfall. But this is between you and I, nobody else will know. I believe that everybody in the East End should be able to have an overseas holiday each year.’ It endeared him to me and made a big impression. When I woke in Switzerland, the sight of the lakes and the mountains was such a contrast to Elder St, and when we came back from our fortnight away I got very down – depressed, you would say now. I was the only non-Jewish person in the Brady Club, only I didn’t realise it. On one of the weekends at Skeate House, I did the washing up and dried it with the yellow towel on a Saturday. But Yogi Mayer said, ‘I won’t tell anyone.’

A friend of my brother’s worked in Savile Row and I thought it would be good for me too. I went to French & Stanley just behind Savile Row and they said they did need somebody but not just yet. So then I went to G.Ward & Co and asked if they wanted anybody, and there was this colonel type and he said, ‘Start tomorrow!’ I was fifteen and a bit, I had left school that Christmas-time. It lasted a couple of years and they were good to me. The cutter would give you the roll of work to be made up and say, ‘It’s for a friend of yours, Hugh Gaitskell.’ When I asked the manager what this meant, he said, ‘We’re Labour and they’re not.’

In 1964, I left Elder St for good, when I got married. I met my wife Margaret at work, she was the machinist and I was the cutter. She used to bring in Greek food and I liked it, and she said, ‘Would you like to come and have it where I live? You’ll have no excuse for forgetting the address because it’s Neville Rd!’

When I started in tailoring, the rateable value of the houses in Elder St was low because of the sitting tenants and low rents, and nobody ever moved. We thought it was good, it was a kind of security. The money people had they spent on decorating and, in my memory, it was always warm and brightly decorated. There was a good sense of well-being, that did seem generally to be the case. We were offered to buy both the houses, five and seven Elder St, for eighteen hundred quid but my father refused because we didn’t want them both.”

Neville with his grandmother.

Neville’s mother Ada Sims.

Neville’s father Charles Turner was in the fire service during the war (fourth from left in back row).

Neville as a schoolboy.

Neville’s ration book.

Coker’s Dairy in Fleur de Lis St used to take care of their regular customers – “If you were loyal to them, they’d give you an extra piece of cheese under the counter.”

Neville aged eleven in 1951, photographed by Griffiths of Bethnal Green.

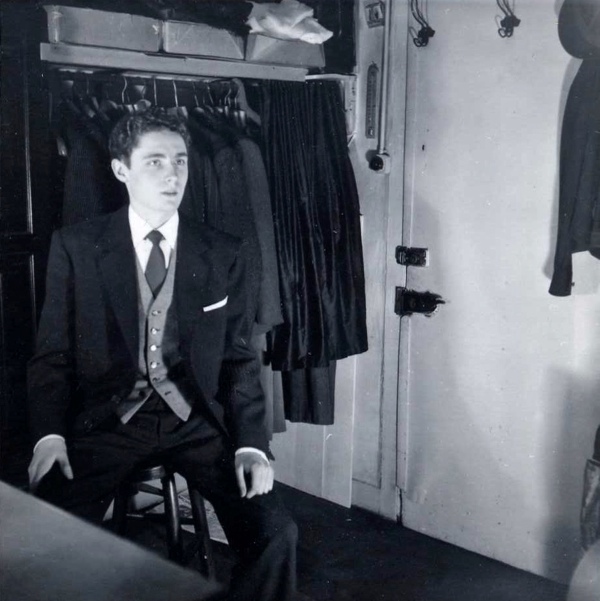

Neville at Saville Row when he began his career as a pattern cutter at sixteen.

Neville’s friend Aubrey Silkoff, photographed when they hitched to Amsterdam in 1961.

Neville’s father Charles owned the only car in Elder St – “We had a car in Elder St when nobody had a car in Elder St, but it vanished when we had no money.”

Neville as a young man.

A family Christmas in Elder St, 1968 – Neville sits next to his father at the dinner table.

Neville’s father, Charles.

Neville and Margaret.

Margaret and Minas.

Neville, Margaret and their son Minas.

Neville’s Uncle Arthur who hung the wisteria wallpaper.

Minas and Terry.

The living room of number seven photographed by the Spitalfields Trust in 1977 with Uncle Arthur’s wisteria wallpaper hanging off the walls.

Dan Cruickshank and others staged a sit-in at number seven to save the house from demolition in 1977.

Neville Turner outside number seven Elder St where he grew up.

You may also like to read about Neville’s childhood friend

The Dogs Of Old London

Click to enlarge

Sometimes in London, I think I hear a lone dog barking in the distance and I wonder if it is an echo from another street or a yard. Sometimes in London, I wake late in the night and hear a dog calling out to me on the wind, in the dark silent city of my dreaming. What is this yelp I believe I hear in London, dis-embodied and far away? Is it the sound of the dogs of old London – the guard dogs, the lap dogs, the stray dogs, the police dogs, the performing dogs, the dogs of the blind, the dogs of the ratcatchers, the dogs of the watermen, the cadaver dogs, the mutts, the mongrels, the curs, the hounds and the puppies?

Libby Hall, who has gathered possibly the largest collection of dog photography ever made by any single individual, took me down to the Kennel Club in Mayfair yesterday to show me her trove in the archive there. Libby was complicit with me in my quest. Surrounded by oil paintings of pooches in the heroic style by great masters such as Sir Edwin Landseer, we took Libby’s treasured photographs from their storage boxes, spread them out upon the polished table top and began to look.

We were seeking the dogs of old London in her collection. We pulled out those from London photographic studios and those labelled as London. Then, Libby also picked out those that she believes are London. And here you see the photographs we chose. How eager and yet how soulful are these metropolitan dogs of yesteryear. They were not camera shy.

The complete social range is present in this selection, from the dogs of the workplace to the dogs of the boudoir, although inevitably the majority are those whose owners had the disposable income for studio portraits. These pictures reveal that while human fashions change according to the era and the class, dogs exist in an eternal universal present. Even if they are the dogs of old London and even if in our own age we pay more attention to breeds, any of these dogs could have been photographed yesterday. And the quality of emotion these creatures drew from their owners is such that the people in the pictures are brought closer to us. They might otherwise withhold their feelings or retreat behind studio poses but, because of their relationships with their dogs, we can can recognise our common humanity more readily.

These pictures were once cherished by the owners after their dogs had died but now all the owners have died too, long ago. For the most part, we do not know the names of the subjects, either canine or human. All we are left with are these poignant records of tender emotion, intimate lost moments in the history of our city.

The dogs of old London no longer cock their legs at the trees, lamps and street corners of our ancient capital, no longer pull their owners along the pavement, no longer stretch out in front of the fire, no longer keep the neighbours awake barking all night, no longer doze in the sun, no longer sit up and beg, no longer bury bones, no longer fetch sticks, no longer gobble their dinners, no longer piss in the clean laundry, no longer play dead or jump for a treats. The dogs of old London are silent now.

Arthur Lee, Muswell Hill, inscribed “To Ruby with love from Crystal.”

Ellen Terry was renowned for her love of dogs as much as for her acting.

W.Pearce, 422 Lewisham High St.

This girl and her dog were photographed many times for cards and are believed to be the photographer’s daughter and her pet.

Emberson – Wimbledon, Surbiton & Tooting.

Edward VII’s dog Caesar that followed the funeral procession and became a national hero.

A prizewinner, surrounded by trophies and dripping with awards.

The Vicar of Leyton and his dog.

The first dog to be buried here was run over outside the gatekeeper’s lodge, setting a fashionable precedent, and within twenty-five years the gatekeeper’s garden was filled with over three hundred upper class pets.

Libby Hall, collector of dog photographs.

Photographs copyright © The Libby Hall Collection at the Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to read my original profile

Libby Hall, Collector of Dog Photography

You may also like to take a look at

At Gaby’s Deli

It is my pleasure to welcome this report from the West End by Jenny Linford accompanied with photographs by Simon Mooney. The only independent cafe around Leicester Sq, Gaby’s Deli is a London institution where you can dine for as little as five pounds and discover yourself rubbing shoulders with West End stars too. After a threat of closure by the landlord, a popular campaign won a reprieve but now Gaby is on a monthly lease which offers no security. So we thought it an opportune moment to celebrate the wonders of this cherished cafe and Gaby Elyahou himself, the man who brought falafels to London.

For as long as I can remember, Gaby’s Deli on Charing Cross Rd has been part of my London cityscape. Just down from the Wyndham Theatre, it is a familiar West End presence – a modest façade with Gaby’s trademark colourful salads proudly displayed in the window. Since last year, this modest, down-to-earth eaterie has been under threat, with Gaby given notice to quit by his landlords, Gascoyne Holdings.

“I’ve been here since 1964,” explains Gaby, a sprightly, dapper figure, with a shrewd face and wonderfully alert eyes. “It was a salt beef bar before I took it over. I added more dishes, bought an espresso machine, started to concentrate on the salads – we do thirty-seven, all home-made. The people who eat here, they know about salt beef. It’s a meal. You can see how much meat we put in the sandwich. I think it’s the best sandwich in the world. I mean it. What other sandwich can you have so much meat in?”

As we chat, Gaby insists on ordering me a plate of his falafel to sample. It arrives promptly – a generous serving of crisp, freshly-fried falafel on a bed of humous, topped with foul medames, then tahini, sprinkled with parsley, with two warm pitta bread on the side. Truly tasty food. Watching Gaby in action, teasing the old ladies sitting to our left, calling out a friendly greeting to a customer walking by, noticing that a customer needs sugar for his coffee, I realise, however, it is not simply the good, fresh food and the reasonable prices which bring people back here time and time again. This is a place with a human face to it. Gaby is one of a fast-vanishing breed of proper, old school proprietors – alert, democratic, experienced, proud of his business, relishing the face-to-face contact with all his customers, gloriously nosy and interested in everyone who comes in. As a result, in a world where clonetown franchises dominate, Gaby’s has that rare quality – personality.

“There are too many chains around here now,” says Gaby thoughtfully. “We serve home-made soup, really filling, moussaka, meatballs, goulash. We have a special every day,” he gestures towards the board. “Tell me – in the West End, where else can you sit and eat a meal for six or seven pounds? I don’t have tablecloths or a waiter with a white starched short, but all the food is freshly made. We get in at 8am – we have to prepare the food. It’s a lot of work. Eating a sandwich – that’s boring! There are too many sandwich shops. We get a lot of theatre people, always have done, always actors. They want something light before the show, so they have a salad.”

“People come back here. We have customers returning from America, Scandinavia, South Africa, from Timbuktu – they come from all over the world. I just had a customer tell me that his grandparents from South Africa always come here when they’re in London, so they told him to come.”

The announcement that Gaby’s was being closed down saw an extraordinary response from his customers, with their Campaign to Save Gaby’s launched on Facebook quickly attracting thousands of supporters. A series of Falafel Cabarets were launched, with Gaby’s thespian customers, such as the actors Henry Goodman and Simon Callow, generously performing to help spread the word.

Among the Save Gaby’s team is Steve Engelhard, who explains why he joined the campaign. “I’ve known Gaby’s for many years. I think it was my big brother who first alerted me to it. We’re a family with Jewish origins – so salt beef, falafel, salads are comfort food as far as I’m concerned. Gaby’s is affordable, it’s unpretentious, the quality is high and it’s very individual – there’s none of the blandness which goes with chains. When I heard that Gaby’s was threatened, I thought I’ve seen too many of my favourite places closing. I’m not a campaigner by habit but it pleases me no end that there’s such a community of people willing to make a stand about this. I think it’s a sense of maintaining a personal landscape, a personal identification with something that contributes to the quality of life and to the soul of London. Without individual places like Gaby’s, the West End could easily be as bland as any standard high street.”

The affection in which Gaby’s is held is almost palpable. Gaby’s customers, when they realise that I am writing about the Save Gaby’s campaign, are eager to tell me what Gaby’s means to them. A middle-aged man, who has been sitting together with his wife and young daughter eating a meal at a table next to me, stops unprompted to talk to me. “I first came here in my early twenties, so have been coming here for twenty-five years now. It would be a terrible shame if it went. It’s a disgrace that Westminster Council didn’t protect it. Walk to Leicester Sq – all you see are crappy pizza and pasta restaurants. They should be protecting this – tourists want London proper, not chain London. This is an iconic, one-off restaurant.” An elegantly-dressed, elderly gentleman pauses shyly on his way out to tell me “I’ve been coming here for decades. It’s desperately sad. So much of London is under threat. It seems wrong that someone who’s been here for so long can be kicked out when so many people care about it.”

Gaby himself is touched by the campaign, wryly amused at the fuss his customers are stirring up. “It was all from the customers. People came and said “We’re not going to let you go.” Boris Johnson, Ken Livingston, actors – they all come here to show support. The newspapers, TV they’ve all come here. I know a lot of people. Fifty years here, it’s not three months. I hope they don’t spoil the West End, but I think they will.” He pauses and shrugs expressively. A neatly printed notice sellotaped to the counter behind him reads: ‘Thank you to our customers who set up and signed up to Save Gabys Deli on Facebook. We are very touched by all your support. The management and team at Gaby’s.’

“The only hope,” explains Steve Engelhard from the Save Gaby’s campaign, “is to change the mind of Gascoyne Holdings and its directors, notably Lord Salisbury – because everything else has been tried. Westminster have granted the planning consent. The only remaining hope is to change the minds of the owners. We’ve had huge press coverage. The question is do these people want to minimise the bad publicity they’re getting? Do they want to be clever and get good publicity for doing the right thing in the end and saving a well-loved institution?” If affection and loyalty alone were enough to save Gaby’s deli, then its future would absolutely be assured.

Photographs copyright © Simon Mooney

Gaby’s Deli, 30 Charing Cross Road, London, WC2H 0DE

You may like to write direct to Lord Salisbury – The Marquess of Salisbury, Hatfield House, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, AL9 5NQ