Colin O’Brien’s Pellicci Portraits (Part 5)

Celebrating the re-opening today, after the holidays, of E. Pellicci, 332 Bethnal Green Rd, it is my delight to publish Part Five of Colin O’Brien‘s Pellicci Portraits recording the regular customers at London’s best-loved family run cafe – in business since 1900 and still going strong. Newcomers are advised to try to memorise these faces, because you may be sat in front of one of them next week, and remember to ask, “Do you you come here often?”

Tommy Peel – “I’ve been coming to Pellicci’s every day since I was a little boy, more than sixty-nine years.”

Melanie Morroll – “I’ve been coming to Pellicci’s regularly for a few years now.”

Sam Way, Supermodel – “I first came to Pellicci’s last January and now I come every week.”

Alison Clare – “I’ve been coming to Pellicci’s once or twice a week for a few years.”

“The Handsome Glaswegian” George Rankin – “I’ve been coming to Pellicci’s for the last fifty-seven years, since I came down frae Glasgow in 1956.”

Sally Knight – “I’m an East Ender and I’ve been coming to Pellicci’s for fifteen years. I come for the fry-ups but I also come for the special benefits.”

Photographer Goswin Schwendinger – “I used to come daily when I first moved here because I knew no-one and this was my family.”

Jenni Johnston – “I am a student of English literature at Queen Mary College and this is my last day at Pelliccis because I’m going back to California tomorrow – but I like it better here!”

Ian Puddick – “I go for training at the Repton Boxing Club each Wednesday and I’ve been coming into Pelliccis with the guys every week for seven months.”

Anna Maybanks – “I’ve been coming regularly for maybe two and a half years. I used to work down the road, but now I am here to visit my friend – which is a good opportunity to come in to Pellicci’s because I miss it so much.”

“BBC Bob” Williams – “My mother brought me into Pellicci’s when I was five and now I’m sixty-five. Nevio used to sit on my lap when he was a little baby, and I remember when Maria first came here from Tuscany.”

Terry Martin – “I came to Pellicci’s for the first time thirty years ago and I’ve been a regular for the past twenty-five years.”

Jill Schweitzer – “My first time at Pelliccis, from San Francisco.”

Brian Kasserer – “I used to come to Pellicci’s quite frequently twenty years ago!”

Fozia Khalig – “I’ve been coming to Pellicci’s once a week since 2007, I’m an addict for Italian food.”

Photographs copyright © Colin O’Brien

You may like to take a look at

Colin O’Brien’s Pellicci Portraits ( Part One)

Colin O’Brien’s Pellicci Portraits (Part Two)

Colin O’Brien’s Pellicci Portraits (Part Three)

Colin O’Brien’s Pellicci Portraits (Part Four)

and read these other Pellicci stories

Maria Pellicci, The Meatball Queen of Bethnal Green

and see these other Colin O’Brien stories

Colin O’Brien’s Clerkenwell Car Crashes

Colin O’Brien’s Kids on the Street

Travellers’ Children in London Fields

Colin O’Brien’s Brick Lane Market

Vigil at Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen

“The in-between days are always quiet but I can’t seem to keep from the shop…”

Yesterday, I ventured from the house into the wet streets for the first time since Christmas Eve and, even at ten in the morning, the pavements were empty with many shops closed and few customers in those that were open. Yet I knew that Paul Gardner, the lone paper bag seller, would reliably be discovered sitting behind the counter at Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen at this time of year, opening for business at six-thirty as usual while the rest of the world slept.

As the fourth generation in Spitalfields’ oldest family business, Paul cannot keep away from his shop which has operated from the Peabody Building in Commercial St since his great-grandfather James Gardner, the Scalemaker, opened up as one of the first tenants in 1870. Once upon a time, James peered through his window to the Royal Cambridge Theatre opposite – a vast music hall with a capacity of three thousand which filled the entire block, and where some claim Charles Chaplin made his stage debut – replaced in the nineteen thirties by Godfrey & Phillips Cigarette factory that stands today in the same location.

Through all these years, a Mr Gardner has sustained a routine of shop-keeping that, over more than a century has surpassed all others in the neighbourhood for its longevity. Thus, Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen has become the place where time has been measured out in scales and parcelled out in paper bags in Spitalfields.

At this season, when the clocks wind down before the momentum regains its pace in the New Year, Paul waits behind his counter in the empty shop, maintaining a conscientious vigil by choosing to be present lest a customer should come along. A seasoned professional at waiting, Paul sits ever-hopeful of custom and, in the normal run of things, his expectation is always fulfilled. Yet, at this time of year, he accepts that the vigil maybe without result, and so I went along to keep him company in the shop for the last hours of business at the end of the hundred and forty-second year of Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen.

“The in-between days are always quiet but I can’t seem to keep from the shop,” he admitted to me, “This week, it’s been a labour of love though, because I must confess I don’t like waiting. But then, it’s nice to come in and have a relaxed time. Last week, I didn’t even have a moment to write up my diary each morning.”

“I got up at four forty-five and left home to come here at five-thirty today.” he continued with a yawn, “I was delivering bags to the Beigel Bakery in Brick Lane at six-fifteen, they were pleased to see me but I suppose I’ve only had four or five customers since then.”

Until I arrived, Paul had spent the morning studying his copy of Classic Rock magazine with one eye upon his Ford Fiesta parked directly across the road. Whereas in the week before Christmas, there had been a line of people preventing me getting in the door, now I was able to settle down upon a pile of paperbags to pass the time quietly with Paul while we awaited the sole customer he was expecting – someone from the gift shop at the Tower of London was coming to collect an order of paper bags.

The novelty of the season was a pile of shapeless pieces of knitwear in assorted random colours beside the counter which provided us with a source of innocent amusement. “My mother broke her wrist and decided she was going to make herself useful by knitting coats for dogs,” Paul explained, flourishing one proudly, “All the dogs in Frinton already have them.”

“Thursday was a complete waste of time,” he announced in good-humoured frustration, returning to the theme of the moment as the silence of the season gathered around us again and we were brought back to waiting, “I don’t mind coming to work but I think I took ten pounds, I should have taken an extra day off. For once, I closed early and then this guy rang up to ask where I was!”

The telephone rang, shattering the calm of the empty shop. Could it be a customer on the hot-line demanding a vast bulk order of paper bags? “Bishopsgate 518” answered Paul expectantly, his constant mantra on lifting the phone, as the call was revealed to be Mr Sammy from the Beigel Bakery ringing to send his New Year Greetings. And then a skinny young Portuguese man with barely a word of English arrived with a trolley from the Tower of London giftshop. We stacked it up with the blue candy-striped bags that suit souvenirs from the Tower of London, and the Portuguese fellow found the language to explain that he was a Tottenham supporter before he wheeled off his barrow of bags through the falling rain.

It was past two now and with the last packet of bags despatched to the Tower, the working day ended at Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen. We had overseen the passage of time. We shook hands, exchanging New Year Greetings and I left Paul to lock up and close the door on Spitalfields for another year. “I’m going to go to bed for an hour when I get home,” he informed me, suddenly energised with a gleam of mischeivous anticipation in his eye, “We’ve got some members of the Havering Youth Orchestra coming round. My son Robert plays the euphonium in it. And I’m going to be crashing the pots and pans at midnight, because I’m the leader of the pack.”

“Even at ten in the morning, the pavements were empty with many shops closed…”

“I ventured from the house into the wet streets for the first time since Christmas Eve…”

“All the dogs in Frinton have them already…” A new line for 2013 at Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen, dog coats knitted by Paul Gardner’s mother.

Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen reopens at 6:30am on 2nd January 2013, 149 Commercial St, London E1 6BJ (6:30am – 2:30pm, Monday to Friday)

You may also like to read about

Paul Gardner, Paper Bag Seller

At Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen

The Tombs of Old London

Monument to Lady Elizabeth Nightingale, Westminster Abbey, c.1910

What could be more uplifting in this festive season than a virtual tour of the Tombs of Old London, courtesy of these glass slides once used by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society for magic lantern shows at the Bishopsgate Institute? We can admire the aesthetic wonders of statuary and architecture in these magnificent designs, and receive an education in the history and achievements of our illustrious forbears as a bonus.

In my childhood, no Christmas was complete without a family visit to some ancient abbey or cathedral. Yet while – ostensibly – we went to admire the tree and the crib, our interest was always drawn by the stone tombs and ancient monuments which consistently offered more extravagant rewards for our attention than the seasonal fripperies. Thus it was that my fascination with mortality became intertwined with Christmas, even before my nearest and dearest began to slip away from me into their graves – until today I have no other members of my family left alive.

In recent years, several of my relatives died at this season – imbuing festivities since then with an inescapable grave resonance. First, my grandmother expired one Boxing Day and, ten years later, my mother died on 31st December just as the daylight was fading. Then, a few years ago, my oldest friend collapsed unexpectedly on Christmas Eve. Consequently, while others delight to whoop it up over the holidays, I prefer to seek peace. Let me confide, my enduring image of New Year’s Eve will always be that of the undertakers carrying my mother’s body from the house out into the darkness.

It is a human impulse to challenge the ephemeral nature of existence by striving to create monuments, even if the paradox is that these attempts to render tenderness in granite will always be poignant failures, reminding us of death rather than life. Yet there is soulful beauty in these overwrought confections and a certain liberating consolation to be drawn, setting our modest personal grief against the wider perspective of history.

Tomb of Sir Francis Vere, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Monument to William Wilberforce, Westminster Abbey, c.1910

Memorial to Admiral Sir Peter Warren, Westminster Abbey, c.1910

Monument to William Wordsworth in Baptistery, Westminster Abbey, c.1910

St Benedict’s Chapel, Westminster Abbey, c.1910

Chapel of St Edmund, Westminster Abbey, c.1910

Tombstone of Laurence Sterne, St George’s Hanover Sq, c.1910 – Buried, grave-robbed and reburied in 1768, subsequently removed to Coxwold in 1969 due to redevelopment of the churchyard.

Hogarth’s tomb, St Nicholas’ Churchyard, Chiswick, c.1910

Sir Hans Sloane and Miller Monuments in Old Chelsea Churchyard, c. 1910

Stanley’s Monument in Chelsea Church, c. 1910

Sanctuary at All Saint’s Church, Chelsea, c. 1910

Shakespeare’s memorial, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Colville Monument in All Saint’s Church, Chelsea, c. 1910

Tomb of Daniel Defoe at Bunhill Fields Burial Ground, c. 1910

At the gates of Bunhill Fields, c. 1910

Tomb of John Bunyan, Bunhill Fields Burial Ground, c. 1910

North Transept of Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

North Ambulatory, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Ambulatory, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Monument to John Milton, St Giles, Cripplegate, c. 1910

Offley Monument, St Andrew Undershaft, c. 1910

Pickering Monument, St Helen’s Bishopsgate, c. 1920

Plaque, Christ Church, Newgate, 1921

Tombs in Temple churchyard, c. 1910

King Sebert’s Tomb, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Monument to Historian John Stow in St.Andrew Undershaft, c. 1910

Tomb of Edward III, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Queen Elizabeth I’s Tomb, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Tomb of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Monument to Charles James Fox, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Poets’ Corner with David Garrick’s Memorial, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Memorial to George Frederick Handel, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Monument to Francis Holles, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Tombstone of the Kidney family, c. 1910

Cradle monument to Sophia, Daughter of James I, Henry VII’s Lady Chapel, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Tomb of Sir Francis Vere, Chapel of St John the Evangelist, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Tomb of John Dryden, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Wellington’s Funeral Carriage, St Paul’s Cathedral,c. 1910

Robert Preston’s grave stone, St Magnus, c. 1910

Tomb of Henry VII, Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Glass slides copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

The High Days & Holidays of Old London

The Lost Squares Of Stepney

William Palin evokes the lost glories of two of the East End’s forgotten architectural wonders, Wellclose Sq and Swedenborg Sq.

In Wellclose Sq – “This unfortunate and ignored locality”

“The devastation of the square was pitiful to see. I only saw one man all the time I paced the square, and he had one foot in the grave. The April evening was chill and the sky overcast, but a blackbird warbled in the plane trees, introducing impromptu variations and evidently trying to keep his courage up. The half dozen Georgian terraced houses left on the north side looked indescribably weary and exhausted, their bricks crumbling and their stucco returning to sand. Grass was coming up on the pavement.”

When Geoffrey Fletcher ventured off Cable St into Wellclose Sq in the spring of 1968, he stumbled upon an eerie scene. Earmarked for redevelopment and languishing under a Compulsory Purchase Order, the entire square – the oldest and most historically important in East London – was about to disappear. Its destruction, together with Swedenborg (originally Princes) Sq, a smaller neighbour to the east, erased two and a half centuries of history and ripped the heart out of this remarkable enclave of forgotten London.

The growth of the eastern suburb of London during the seventeenth century was a phenomenon. Even before the development boom which followed the Great Fire, busy hamlets had grown up outside the City’s eastern boundary and along the northern banks of the Thames where thriving communities serviced, and profited from, growing river trade.

Detail of John Rocque’s Map of London (1746) showing Wellclose Sq and Princes Sq.

One speculator who recognised the potential for profit east of the City was the notorious Nicholas Barbon who is said to have laid out a staggering £200,000 in building in London after the Great Fire. In 1682, Barbon leased the Liberty of Wellclose (or Well Close) – a parcel of land north of Wapping – from the Crown. Barbon intended his new development on the Wellclose to appeal to the well-to-do members of the East End’s maritime community. Following the Great Fire, the riverside neighbourhoods had been swelled by the influx of new immigrants profiting from the rebuilding of the city.

The huge demand for timber created a lucrative trade for the Scandinavians, and the Norwegians (Danish subjects until 1814) were said to have “warmed them selves comfortably by the Fire of London.” Anglo-Danish connections had been strengthened by the marriage in 1683 of Princess Anne (later Queen Anne) to Prince Georg of Denmark and it was Georg’s father, King Christian V, who supplied the most of the funds for the construction of the new Danish Church at Wellclose Sq.

Danish-Norwegian Church in Wellclose Sq engraved by Johannes Kip in 1796.

The architect was the Danish sculptor Caius Gabriel Cibber. Cibber (the son of the King of Denmark’s cabinet-maker) had trained in Italy and had worked for Wren at St Paul’s. He is perhaps best known for his figures of ‘Raving’ and ‘Melancholy Madness’ made for the entrance to Bethlehem Hospital. Cibber’s new Danish Church at Wellclose Sq was completed in 1696. It was baroque in style, in the manner of Wren’s City churches and, its interior was distinguished by a vaulted ceiling with a distinctive circular central boss fringed with ornament.

The Old Court House, Wellclose Sq (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

A number of the original seventeenth-century houses on the south side of the square survived until the nineteen sixties and photographs show them to be of good quality, with well-proportioned panelled rooms, and staircases with twisted balusters. Yet, other than the church, the most important and beautiful building in the square was the Old Court House, on the corner of Neptune St, built after 1687 as the seat of Justice for the four Tower Liberties. Its fine staircase and rooms of bolection panelling, identify it as part of Barbon’s first development. One of the prison cells from the building was later re-assembled and is now on display at the Museum of London.

The former Danish Embassy, c.1930. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Other buildings of note in the square included Nos 20 & 21 on the west side which once housed the Danish Embassy. The two charming sculpted reliefs featuring putti practising the arts and sciences were removed to the Norwegian Embassy in Belgravia in the nineteen sixties. Also on the west side, stood two extraordinary relics of eighteenth-century maritime London. At the corner of Stable Yard was No.26, a timber framed weather-boarded house, complete with Venetian window, and, in the yard behind, there was a five-bay boarded house which in appearance recalled a North American East Coast colonial mansion.

At the corner of Stable Yard, Wellclose Sq. (London & Middlesex Archaeological Society, Bishopsgate Institute)

By the early nineteenth-century, the square was losing its respectability as a consequence of its proximity to the docks and the gradual industrialisation of the East End. The enclosure of the docks meant that seamen could leave ship during the unloading and loading of cargo. “Houses of ill-fame are swarming,” complained a contemporary Wesleyan missionary, “the neighbourhood teems with lazy, idle, drunken lustful men, and degraded, brutalised hell-branded women, some alas! girls in their early teens.”

As the numbers of lodging houses, pawn shops, pubs, and music halls multiplied, so did the sugar refineries. These refineries (or ‘bakeries’) had first appeared in the area in the seventeen-sixties. Manned mainly by poor German immigrants and belching sickly fumes into air, they did not help to improve the desirability of the neighbourhood. By the eighteen-fifties, there were at least five refineries operating around the square.

In 1816, the church was handed to trustees for charitable uses in aid of Danish and Norwegian seamen in London and, in 1856, the church became a mission under the control of St George-in-the-East only to be demolished and replaced by the new St Paul’s School in 1870.

The early success of Wellclose Sq inspired another Scandinavian community to undertake a similar development. Princes Sq (renamed Swedenborg Sq in 1938 after Emmanuel Swedenborg, who was interred there in 1772) was laid out in the seventeen-twenties by the Swedish community. It featured a plainer version of the Danish church, also positioned at the centre of the square inside a railed burial enclosure with high gates.

The Swedish Lutheran Church in Swedenborg Sq in December 1908. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

The Swedish congregation abandoned the building in 1911, moving west to Harcourt St in Marylebone, and the church, stripped and empty, deteriorated quickly. Photographs from 1919 show the windows broken and the railings torn down. Finally, in 1923, the site was purchased by the council, cleared, and replaced by a children’s playground. The east, west and south sides of the square had gone up in the seventeen-twenties and the north side a century later. Like Wellclose Sq, the south side contained some larger houses and most of these survived until the nineteen sixties.

South side of Swedenborg Sq, 1945. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

The seventeen-twenties terrace on the west side of the square was particularly fine, with handsome Doric doorcases and high basements. After World War II, the square was surveyed by the borough architect who concluded that the houses were in good order “excepting for want of attention due to the war” and “worthy of preservation on architectural grounds.” Subsequent repair work was carried out and a comparison of the photographs taken in 1945 with those of the late fifties and early sixties show that many of the buildings have been carefully rehabilitated.

Houses on the west side of Swedenborg Sq in 1945. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Houses in Swenborg Sq after Post-War repair in 1961. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

This revival was short-lived however. In March 1959, a chilling memo from the LCC Valuer recorded that seventeen Grade II and twelve Grade III buildings in the square have been declared a “SLUM.” This change in the way the buildings were perceived must be seen against a background of political change and pressure for removal of the older London neighbourhoods in favour of modern, planned estates. A Compulsory Purchase Order (CPO) is set in motion and, at an inquiry in 1961, the Inspector concluded that the buildings were not capable of preservation.

Within a decade Swedenborg Sq had disappeared completely beneath the Swedenborg Gardens and St Georges Housing Estate – the area was simply erased from history. At Wellclose Sq, the houses came down too but the street pattern was retained, creating a strange non-place. Forty years on, the south side of the square remains empty and, on the site of the Old Court House, a sad wasteland stretches down to the busy Highway beyond.

Visiting in 1966, with the squares on their last legs, the historian and journalist Ian Nairn, who wrote so perceptively about the “soft-spoken this-is-good-for-you castration of the East End,” summed up the terrible plight of these two architectural jewels.

“Embedded in it (Cable St) are the hopeless fragments of two once splendid squares, Wellclose and Swedenborg, built for the shipmasters of Wapping when London began to move east. Those who could care about the buildings don’t care about the people, those who care about the people regard the decrepit buildings rather as John Knox regarded women: unforgivable blindness. Nobody cares enough, and the whole place will soon be a memory.”

Danish and Norwegian Church in Wellclose Sq, c.1845, by unknown artist.

Liberties of the Tower 1720, including Marine Sq, Spittle Fields and Little Minories.

Interior of the Danish-Norwegian church engraved by Kip in 1796.

Geoffrey Fletcher’s drawing of Wellclose Sq, 1968.

Wellclose Sq looking east from the steps of No.5 (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Wellclose Sq, south side, 1961. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Old Court House, view to first floor landing showing the fine Barbon staircase, 1911 (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Watch House, Wellclose Sq, 1935. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Interior of Swedish church, 1908. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Swedish church, 1919. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Swedenborg Sq, south side looking east, 1921 (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

You may slso like to read about

In the Debtors’ Cell, Wellclose Sq

David Mason, Wilton’s Music Hall

John Claridge’s Darker Side

Photographer John Claridge sent me this set of pictures entitled “East London, A Darker Side And Objects of Affection,” yet when I asked him which of the images referred to darkness and which to veneration, he became evasive. Justly celebrated for his subtle appreciation of tonal contrast in photography, John sees darkness and light as inextricable from each other in life too.

For John, these images are tokens of the East End that he knew and of the East End that made him. They are plates from an unwritten autobiography. When, at fifteen years old, John went up west to work in advertising at McCann Erickson, the college graduates would not speak to him at first, dismissing him as being from the “wrong side of the tracks.” But John refused to apologise for his origins and quickly discovered that he was accepted by creative figures at the agency such as the designer Robert Brownjohn who recognised his nascent talent.

Many of the objects in these pictures are still in John’s possession today, carried all these years as talismans of his youthful emotional universe in the fifties and sixties. Yet they also speak of the violence of that society, a violence which John witnessed and knew personally, but does not sentimentalise. “It’s a world I flirted with, but film delivered me to another life,” John admitted, choosing his words carefully and looking back with a clear-eyed gaze. It was his and our good fortune that – out of the variety of implements portrayed here – for John the camera proved to be the most eloquent means of self-expression.

The Beginning -“My first serious camera when I was fifteen, bought by hire purchase. I still have it, but it’s resting now.”

Once Upon a Time in the East End – “A Magnum twelve gauge shotgun laid upon the grill in an East End St.”

Eldorado & The Dark Corner – “My first car was a V8 Ford Pilot, but an American car was the most desirable and I photographed a friend’s Eldorado Cadillac on a street off the Highway.”

Zip Gun – “At school, we used to get hold of toy guns and use them to create real guns. You use small ball bearings, pack it with gunpowder and it fires. It was what we did.”

The Starter – “I found a razor in the street once. There had been a fight and it was left behind. I remember seeing Teddy Boys in the market buying razors with mother of pearl handles, and they’d put them in their top pocket to see which matched their clothes best. Their opening line was, ‘Do you want to start something?'”

This is Not a Negative – “I used to carry a flick knife, it wasn’t a negative characteristic, it was my life. You learnt to survive.”

How Things Grow

The Unknown Boxer – “My father was a bare-knuckle fighter but he was also the gentlest man you could imagine.”

The Hammers – “The symbol for West Ham , the hammers refer to ship building. I used to compete in athletics for West Ham and I still have my badge.”

Rolling Thunder -“I crashed my bike and got smashed up really badly. I broke an arm, a leg, cracked three vertebrae, broke eight ribs, one rib punctured a lung and I was in a coma for a week. But when I got out of hospital, my mates put me on a bike and made me take the same bends again. It was the biggest adrenalin rush of my life. Motorbiking was an important part of growing up, and I still ride a Ducati 916 and a Harley.”

Stewed or Jellied – “Obviously, I adore eels, stewed or jellied. We’d go on holiday to Southend and eat fresh seafood, so I thought I’d send this postcard back to everyone.”

This is NOT the wrong side – “When I started at McCann Erickson at fifteen, the college graduates wouldn’t speak to me – I was told I was from the wrong side of the tracks.”

Photographs copyright © John Claridge

You may like to read these other stories of the darker side of the East End

Billy Frost, the Krays’ Driver

Sammy McCarthy, Flyweight Champion

or take a look at these other pictures by John Claridge

Along the Thames with John Claridge

At the Salvation Army with John Claridge

A Few Diversions by John Claridge

Signs, Posters, Typography & Graphics

Views from a Dinghy by John Claridge

In Another World with John Claridge

A Few Pints with John Claridge

Some East End Portraits by John Claridge

Sunday Morning Stroll with John Claridge

Just Another Day With John Claridge

At the Salvation Army in Eighties

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round One)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Two)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Three)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Four)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Five)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Six)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Seven)

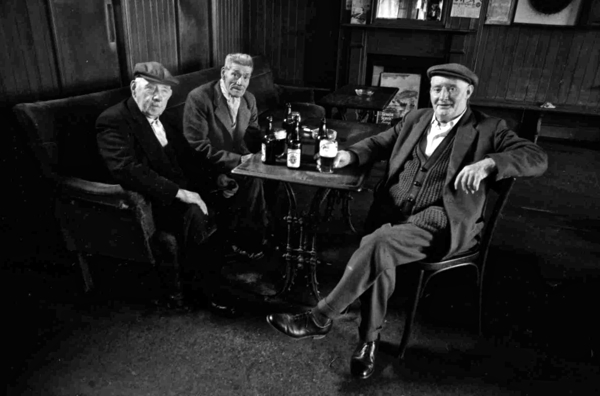

At The Pub With Tony Hall

Libby Hall remembers the first time she visited a pub with Tony Hall in the nineteen sixties – because it signalled the beginning of their relationship which lasted until his death in 2008. “We’d been working together at a printer in Cowcross St, Clerkenwell, but our romance began in the pub on the night I was leaving,” Libby confided to me, “It was my going-away drinks and I put my arms around Tony in the pub.”

During the late sixties, Tony Hall worked as a newspaper artist in Fleet St for The Evening News and then for The Sun, using his spare time to draw weekly cartoons for The Labour Herald. Yet although he did not see himself as a photographer, Tony took over a thousand photographs that survive as a distinctive testament to his personal vision of life in the East End.

Shift work on Fleet St gave Tony free time in the afternoon that he spent in the pub which was when these photographs, published here for the first time, were taken. “Tony loved East End pubs,” Libby recalled fondly, “He loved the atmosphere. He loved the relationships with the regular customers. If a regular didn’t turn up one night, someone would go round to see if they were alright.”

Tony Hall’s pub pictures record a lost world of the public house as the centre of the community in the nineteen sixties. “On Christmas 1967, I was working as a photographer at the Morning Star and on Christmas Eve I bought an oven-ready turkey at Smithfield Market.” Libby remembered, “After work, Tony and I went into the Metropolitan Tavern, and my turkey was stolen – but before I knew it there had been a whip round and a bigger and better one arrived!”

The former “Laurel Tree” on Brick Lane

Photographs copyright © Libby Hall

Images Courtesy of the Tony Hall Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute

Libby Hall & I would be delighted if any readers can assist in identifying the locations and subjects of Tony Hall’s photographs.

You may also like to read

Libby Hall, Collector of Dog Photography

Sign the Petition to save The Marquis of Lansdowne here

At Pellicci’s Christmas Party

Rodney Archer gives his rendition of ‘Santa Claus is Coming to Town’…

A rain storm engulfed the East End early on the Saturday morning before Christmas, yet the foul weather did not discourage me from rolling out of my bed and along the Bethnal Green Rd to the celebrated E.Pellicci before nine in the morning with the hope of witnessing Rodney Archer perform “Santa Claus is Coming to Town.” The golden glow of the cafe interior shone like a beacon through the foul weather as I arrived to be greeted by the Christmas crib with the baby Jesus, angels and shepherds, all just visible through the steamed-up window. Once inside, I joined Rodney at the corner table where he was conscientiously studying the lyrics in advance of his big moment.

Even though the volume of custom was depleted on account of the filthy weather, Nevio Pellicci was not discouraged. He understood that what we lacked in numbers we gained in emotional solidarity as fellow refugees from the storm. And so, taking the initiative in the role of host that is his birthright and which he fulfils so superlatively, he handed out the carol sheets. Striking the metal chimney upon the boiler for the hot water with a spoon, Nevio drew the cafe to order, causing the two tables of families with children to look up with especial eagerness from their fried breakfasts – as he led the assembly in a spirited rendition of “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.”

Photographer Colin O’Brien arrived in the midst of the carol, an expression of wonderment spreading across his face as he stepped from the chilly street into the cafe. And then, it was Rodney Archer’s moment. He stood and sang all the verses of his chosen carol, articulating the lyrics with a practised eloquence, and the entire cafe joined in with “You’d better watch out, you’d better beware, because Santa Claus is coming to town…” Visibly relieved to sit down again during his applause, “I didn’t sleep all night,” he confessed to me wiping the perspiration from his brow, “And now it’s over.”

Yet the concert party was just about to change gear, as the members of the Tower Hamlets Environmental Services Team arrived at the same moment as members of the London Late-Starters Orchestra came in for for breakfast, as they always do when practising in the rehearsal room across the road. Gina Boreham stood up and gave a elegantly modulated performance of “When you’re young at heart,” which brought the cafe to a standstill and then followed it with a soulful version of “When the hangover strikes.”

By now, things were going with quite a swing which prompted Nevio Pellicci to bring out his wedding photos and Maria and her crew to emerge from the kitchen bedecked in tinsel. “When I was a kid, all the stallholders from the market used to come in for hot toddies at this time of year,” Nevio recalled fondly, thinking back to years past, “And I used to get lots of Christmas presents.” Colin O’Brien took the rare opportunity to capture all the Pellicci team in one picture which prompted Nevio to say, “That’s the Christmas card sorted for next year!”

By this time, the rain had relented and it was just growing light outside. There was time for a last collective rendition of “Silent Night” before all realised that – once we had exchanged seasonal greetings – it was the moment to disperse upon our respective Christmas errands, while the saner residents of the East End were yet to stir from their slumbers.

The renowned baritone voice of Nevio Pellicci led the carols.

Gina Boreham

Magda and Maria

“I didn’t sleep all night and now it’s over.”

Silva, Maria, Tony, Nevio, Kinga & Magda

Photographs copyright © Colin O’Brien

You may like to read these other Pellicci stories

Maria Pellicci, The Meatball Queen of Bethnal Green

Colin O’Brien’s Pellicci Portraits ( Part One)

Colin O’Brien’s Pellicci Portraits (Part Two)