Three Events To Delight You Next Week

On Monday 2nd November at 9am, The Gentle Author’s CRIES OF LONDON exhibition opens at Bishopsgate Institute and runs during the Institute’s opening hours until January 29th, 2016

On Tuesday 3rd November at 7:30pm, Phil Maxwell gives a MAGIC LANTERN SHOW at Bishopsgate Institute – showing his photography of BRICK LANE since 1981 and tracing the changing nature of the street from a place of work to a place of recreation. Click here to book

On Thursday 5th November at 6:30pm, Charles Pertwee & The Gentle Author are at Waterstones, Trafalgar Sq, talking about Baddeley Brothers and the history of printing in London over the last two hundred years, and signing copies of BADDELEY BROTHERS. Admission is free but booking essential, ring 020 7839 4411 or email trafalgarsq@waterstones.com

[youtube 1zSCLVcUTqE nolink]

If there is any problem viewing the film please click this link

(Please note the BILLINGSGATE MARKET CHIT-CHAT at Bishopsgate Institute on Wednesday 4th November is completely sold out)

The Dead Man In Clerkenwell

At Halloween, it suits my mood to contemplate the dead man in the crypt in Clerkenwell

This is the face of the dead man in Clerkenwell. He does not look perturbed by the change in the weather. Once Winters wore him out, but now he rests beneath the streets of the modern city he will never see, oblivious both to the weather and the wonders of our age, entirely oblivious to everything in fact.

Let me admit, although some might consider it poor company, I consider death to be my friend – because without mortality our time upon this earth would be worthless. So I do not fear death, but rather I hope I shall have enough life first. My fear is that death might come too soon or unexpectedly in some pernicious form. In this respect, I envy my father who always took a nap on the sofa each Sunday after gardening and one day at the age of seventy nine – when he had completed trimming the privet hedge – he never woke up again.

It was many years ago that I first made the acquaintance of the dead man in Clerkenwell, when I had an office in the Close where I used to go each day and write. I was fascinated to discover a twelfth century crypt in the heart of London, the oldest remnant of the medieval priory of the Knights of St John that once stood in Clerkenwell until it was destroyed by Henry VIII, and it was this memento mori, a sixteenth century stone figure of an emaciated corpse, which embodied the spirit of the place for me.

Thanks to Pamela Willis, curator at the Museum of the Order of St John, I went back to look up my old friend after all these years. She lent me her key and, leaving the bright October sunshine behind me, I let myself into the crypt, switching on the lights and walking to the furthest underground recess of the building where the dead man was waiting. I walked up to the tomb where he lay and cast my eyes upon him, recumbent with his shroud gathered across his groin to protect a modesty that was no longer required. He did not remonstrate with me for letting twenty years go by. He did not even look surprised. He did not appear to recognise me at all. Yet he looked different than before, because I had changed, and it was the transformative events of the intervening years that had awakened my curiosity to return.

There is a veracity in this sculpture which I could not recognise upon my previous visit, when – in my innocence – I had never seen a dead person. Standing over the figure this time, as if at a bedside, I observed the distended limbs, the sunken eyes and the tilt of the head that are distinctive to the dead. When my mother lost her mental and then her physical faculties too, I continued to feed her until she could no longer even swallow liquid, becoming as emaciated as the stone figure before me. It was at dusk on the 31st December that I came into her room and discovered her inanimate, recognising that through some inexplicable prescience the life had gone from her at the ending of the year. I understood the literal meaning of “remains,” because everything distinctive of the living person had departed to leave mere skin and bone. And I know now that the sculptor who made this effigy had seen that too, because his observation of the dead is apparent in his work, even if the bizarre number of ribs in his figure bears no relation to human anatomy.

There is a polished area on the brow, upon which I instinctively placed my hand, where my predecessors over the past five centuries had worn it smooth. This gesture, which you make as if to check his temperature, is an unconscious blessing in recognition of the commonality we share with the dead who have gone before us and whose ranks we shall all join eventually. The paradox of this sculpture is that because it is a man-made artifact it has emotional presence, whereas the actual dead have only absence. It is the tender details – the hair carefully pulled back behind the ears, and the protective arms with their workmanlike repairs – that endear me to this soulful relic.

Time has not been kind to this figure, which originally lay upon the elaborate tomb of Sir William Weston inside the old church of St James Clerkenwell, until the edifice was demolished and the current church was built in the eighteenth century, when the effigy was resigned to this crypt like an old pram slung in the cellar. Today a modern facade reveals no hint of what lies below ground. Sir William Weston, the last Prior, died in April 1540 on the day that Henry VIII issued the instruction to dissolve the Order, and the nature of his death was unrecorded. Thus, my friend the dead man is loss incarnate – the damaged relic of the tomb of the last Prior of the monastery destroyed five hundred years ago – yet he still has his human dignity and he speaks to me.

Walking back from Clerkenwell, through the teeming city to Spitalfields on this bright afternoon in late October, I recognised a similar instinct as I did after my mother’s death. I cooked myself a meal because I craved the familiar task and the event of the day renewed my desire to live more life.

At Tjaden’s Electrical Service Shop

Contributing Writer Rosie Dastgir celebrates a favourite electrical repair shop in Chatsworth Rd

Keith Tjaden

It is easy to miss Tjaden’s Electrical Service Shop, sandwiched between a chic restaurant and the Star Discount Store on Chatsworth Rd in Clapton, but I am on a mission. These days it is hard to find anyone trained in the art and craft of lamp repair and restoration, so I was delighted to discover such a place existed. Keith Tjaden’s shop, like an infirmary for injured lamps, a safe haven for ones like mine that have suffered rough times abroad, was just what I had been seeking.

One evening last summer, I lugged in a batch of battered lamps that had travelled back and forth across the Atlantic with me, and were in need of conversion back to English ways and English voltage. Were they beyond hope of repair?

I return to collect them in early autumn. The radio chunters away in the background as I gingerly push open the shop door. Mr Tjaden himself emerges from the back of the shop with an air of quiet triumph. My pair of skittle shaped lamps, sky blue and pale cream, were damaged on the sea crossing to America and consequently left standing unused in a basement for seven years, half converted, half broken, with the wrong plugs and flimsy cardboard fittings. Designated PIA. by the shop technicians – Previous Inexperienced Attention – they had cut a tatty and sorry sight. Restored to gleaming perfection, Mr Tjaden’s fine workmanship is evident in their transformation. Even so, he is swift to credit the original design and craftsmanship of the lamps, Made in England, for Heal’s – they benefit from good bones, at least, in spite of suffering from PIA.

“The finish is so perfect,” he says, “that all I had to do was run the wax polish over the surface; they’ve not been sanded.” Apparently, it is all about the quality of the molding. The bases are made with powder-loaded resin, using an adhesive mixed with blue powder to get a solid base that won’t chip like a painted version.

Mr Tjaden brings out my beloved pair of thirties lamps that he has restored for me: stacked up glass baubles on chrome cigarette tray bases that I found in a vintage shop in New York’s East Village. The glass baubles are cast, and therefore display no joint lines whatsoever, not something that I’d clocked till he points it out to me. Polished and sparkling, they are even prettier than when I first acquired them. The smart new flex is black. “We use it on almost everything because it matches everything – brass, wood, ceramics.” I learn that electrical flex has a dogged memory, so it retains its kinks and curves. Which is why cable coiling is such an art, flex refuses to repress its memories without a struggle. “Make sure the wire comes out from the inverted cigarette tray, so it doesn’t tip over,” Mr Tjaden tells me.

Meticulous in his work, both aesthetically and technically, Mr Tjaden is very safety conscious and it dawns on me that I am lucky to have escaped with my life after seven years surrounded by such ill-converted lamp and light fittings while I lived in New York.

“Despite the life they’ve had and the travelling they’ve done, they’ve been restored to new,” he says. He shows me the safety label he’s stuck to the newly refurbished base. I feel a glow of pleasure and relief.

After doing national service in the RAF, working on navigational instruments, Mr Tjaden started the business in 1958 with his colleague and senior partner, Mervin, who had a background in TV and radio engineering. They took over the premises on Chatsworth Rd in 1990, moving here from Leystonstone High Rd, when the street was a still a bustling mix of greengrocers and washing machine repair shops, locksmiths and pet shops, carpet dealers and newsagents. Jim’s Café opposite has closed down now, after Dave the proprietor died. The place was a favourite lunch spot serving home made meat pies to all manner of people from the area. Road workers, who parked their barrows outside, sat beside men in suits and teachers who nipped out for a much needed break from Rushmore School up the road.

When families and young people started moving back into Clapton in the nineties, many of the old Victorian and Georgian houses had not been touched since the fifties. ‘They were literally in the dark ages,’ Mr Tjaden recalls, ‘requiring a huge amount of work rewiring from top to bottom. Of course, everyone wanted to be modernized in the fifties and sixties and seventies, but nowadays people want to hold onto their old light bulbs from the past.”

Part of the shop’s appeal and longevity lies in Mr Tjaden’s ability to fuse the old and the new – he enthusiastically embraces change and modern technology, yet clearly retains an affection for antiques and vintage pieces. There is a pre-Weimar lamp being restored for a young barrister couple. A leather box from the twenties, a family piece, used for storing white wing collars, is on display. An old British microphone from the thirtie’s stands in the shadows in the back of the shop, waiting to be hired for a film or photo shoot.

I spot a small gizmo I do not recognize sitting in a glass display cabinet. It is a 1945 radio valve, found inside old radios and radiograms, TVs and amplifiers. It has a heater that warms up the cathode which produces the electrons and comes out on the plate as a rectified signal. The radio valve, like the light bulb, is an endangered species.

Nowadays all lamps repaired in the shop are fitted with the latest incarnation of LED bulb, lighting semi-conducted diode devices. “Filament bulbs or incandescent bulbs are strictly speaking off the market,” says Mr Tjaden, “unless they are extra long life or decorative. They waste energy and don’t produce much light.” I cannot argue with that, though I feel a pang of nostalgia. A typical LED bulb of a mere 4 watts, or 470 lumens, to use the newfangled measure, is rated to last 15,000 hours and provides ample light. The old bulbs are scorching to the touch, and burn out their fixtures. Their days are numbered, and not just because of European Union directives.

There are some happy endings to the demise of the old bulbs. An elderly couple, barely able to discern the dimly-lit surroundings of their living room, were delighted when Mr Tjaden came to the rescue with a dazzling new LED bulb. A single pendant of 1,500 lumens. It did the trick. They will never have to mount a rickety chair to change a bulb again.

“A god send,” Mr Tjaden says. And for a brief flicker, I picture the old couple, instant converts to the new illumination, gathered in the bright circle of light thrown by their thoroughly modern bulb.

Photographs copyright © Colin O’Brien

TJADEN RETRO & VINTAGE ELECTRICAL REPAIRS, 62A Chatsworth Rd, E5 0LS. Vintage, Retro Electrical Light Fitting & Repairs

You may also like to read about

Tony Hawkins & The Cries Of London

I worked through last night to send my CRIES OF LONDON book to the printer today and I am proud to announce it will be published on 26th November. Here I present a film by Contributing Filmmaker Sebastian Sharples on the subject of the Cries, alongside my interview with Tony Hawkins – the retired pedlar who inspired me to study the history and politics of street trading.

[youtube 5z-4zNyHfA0 nolink]

Tony Hawkins testified to me that he sold peanuts and roasted chestnuts in the West End streets for ten years but – after getting arrested and roughed up by the police eighty-seven times – his health failed and he retired.

Whereas Tony used to visit Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen in Commercial Street, Spitalfields, regularly to buy thousands of bags for his thriving business, after retirement he came simply to pass the time of day with his old friend Paul Gardner. And it was Paul who effected my introduction to Tony, a man with a defiant strength of character, frail physically yet energised by moral courage. Brandishing the dog-eared stack of paperwork from his eighty-seven court cases, he was immensely proud that he won every one and it was proven he never broke the law once.

Tony’s pitiful catalogue of his wrangles with Westminster Council – who went to extreme lengths just to prevent him peddling nuts in Piccadilly – reveal that the age-old ambivalence and prejudice against those who seek to make a modest living by trading in the street persists to the present day.

“I was unemployed as a labourer in Manchester, so I started off as a pedlar. I sold socks, balloons – anything really. A pedlar trades as he travels, and the will to support myself and the bright lights brought me to London. I was peddling around the West End selling peanuts mostly but also chestnuts. I sold flags at football matches too, Chelsea and Arsenal.

“In the nineteen-eighties, a sergeant took me to Bow Street Magistrates Court for selling peanuts in Piccadilly. So I went along, it was no big deal. I admitted I was trading and I was a licenced pedlar.

“In Court, they were amazed because thay hadn’t seen many pedlars, there were only half a dozen in the West End. I won the case and I went to shake the sergeant’s hand afterwards, but he pushed me away and said it wasn’t the end of it. He told me he’d do everything in his power to make sure I never worked again and he hounded me after that. He said, “If you’re going to do it again, we will arrest you again,” and I’ve been arrested more than eighty times and spent nights in cells. I’ve been roughed up so many times by policemen and council enforcement officers that I had to get a hidden camera because I feared for my safety.

“They confiscated my stock and equipment from me every time I was charged with the offence of street trading without a licence, when I had a Pedlar’s Licence issued in accordance with the Pedlar’s Act of 1871. The original Act was passed in the eighteenth century so that veteran soldiers could trade in fish, fruit, vegetables and victuals, and be distinguished from vagabonds. Anyone over the age of seventeen can get a pedlar’s licence as long as you have no criminal record. According to the Bill of Rights and the Magna Carta, every person in this country has the right to trade.

“I went to the High Court once when they found against me and the judge overturned it in my favour. But then in 2000 they brought in the Westminster Act because of people like myself. Westminster Council juggled the words so that it states that pedlars are only allowed to go door-to-door.

“Prior to that Act, we were allowed to peddle lawfully anywhere in the United Kingdom but now the Act is also being used to stop pedlars in Newcastle, Liverpool, Manchester, Warrington and Balham. Yet Acts and Statutes are not laws, they are rules for the governance, accepted only by consent of the populace.

“Once, I went to get my stuff back from Westminster Council and I met the Manager of Licencing & Street Enforcement. I asked him, “Why do you continue to waste the money of the council tax payers with so many cases against me when you haven’t won a single one?”

“Your lawyer, Mr Barca, I’m sick of him,” he said, “He only represents the lower end of the market like you, and pimps and prostitutes.” Later, he denied it and said he had a witness too, but I had recorded him and he had to pay four thousand pounds in damages to Mr Barca.

“After being hounded by the council and the police so many times, I’ve become narked and with good reason. Over the years, it has cost me a fortune to pay the legal costs. I had to work to earn all the money to pay for it. I regard myself as downtrodden because I was never allowed to benefit from my hard work, but if I had been allowed to continue trading, I could have owned a house by now and have some money in the bank.”

People say to me,“Why have you done it?” I have done it because I believe in the right to trade freely as a human right.”

Tony is now retired, living comfortably in sheltered housing, and has become a self-taught yet highly articulate expert in the law regarding pedlars and street trading, and he is involved with the Pedlars Information & Resource Centre.

Despite losing his health and his livelihood, Tony has acquired moral stature, passionate to support others suffering similar harassment because they exercise their right to sell in the street. With exceptional perseverance, acting out of a love of liberty and a refusal to be intimidated by authority, Tony Hawkins is an unacknowledged hero of the London streets.

Sarah Ainslie’s Wardrobe Portraits

Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie has been taking portraits of people in their wardrobes since 2002 and she has done over fifty. Today I publish a selection and you can see the whole set on exhibition at 7 Ezra St, E2 7RH for the next two Sundays – October 1st & 8th from 11am until 5pm

Viscountess Boudica of Bethnal Green

Emily Shepherd

Julie Begum

Hydar Dewachi

Madeleine Ruggi

Sara Sheppard

Luke Dixon

Lara Clifton

Shakila

Brand Thumim

Jo Ann Kaplan

Sid Dixon

Penny Woolcock

Prue Ainslie

Simon Hoare-Walter

Jenny Carlin

Lel McIntyre

Ryan-Rhiannon Styles

Ruhela

Francine Merry

Sabeha Miah

Kassandra & Dan Isaacson

Andrew Dawson

Shelagh Ainslie

“Wardrobes are private places where personal belongings are kept, not only clothes but also objects with special meanings and memories. Children see them as spaces where adults hide secrets and I always felt there were secrets in my parents’ wardrobes. As a child, my grandmother’s knicker drawer fascinated me, and we would search for sweeties that she kept in jars and beautiful evening dresses in her wardrobe that she let us touch. My father had a bespoke wardrobe with special racks for shoes and drawers for all his different garments, and my mother had a big walk-in wardrobe. I conceal letters and strange memorabilia, like casts of my teeth, in mine.” – Sarah Ainslie

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You might also like to take a look at

Charles Jones, Photographer & Gardener

In autumn, it is time to savour fruits of the orchard and the field, as photographed by Charles Jones

Garden scene with photographer’s cloth backdrop c.1900

These beautiful photographs are all that exist to speak of the life of Charles Jones. Very little is known of the events and tenor of his existence, and even the survival of these pictures was left to chance, but now they ensure him posthumous status as one of the great plant photographers. When he died in Lincolnshire in 1959, aged 92, without claiming his pension for many years and in a house without running water or electricity, almost no-one was aware that he was a photographer. And he would be completely forgotten now, if not for the fortuitous discovery made twenty-two years later at Bermondsey Market, of a box of hundreds of his golden-toned gelatin silver prints made from glass plate negatives.

Born in 1866 in Wolverhampton, Jones was an exceptionally gifted professional gardener who worked upon several private estates, most notably Ote Hall near Burgess Hill in Sussex, where his talent received the attention of The Gardener’s Chronicle of 20th September 1905.

“The present gardener, Charles Jones, has had a large share in the modelling of the gardens as they now appear, for on all sides can be seen evidence of his work in the making of flowerbeds and borders and in the planting of fruit trees. Mr Jones is quite an enthusiastic fruit grower and his delight in his well-trained trees was readily apparent…. The lack of extensive glasshouses is no deterrent to Mr Jones in producing supplies of choice fruit and flowers… By the help of wind screens, he has converted warm nooks into suitable places for the growing of tender subjects and with the aid of a few unheated frames produces a goodly supply. Thus is the resourcefulness of the ingenious gardener who has not an unlimited supply of the best appurtenances seen.”

The mystery is how Jones produced such a huge body of photography and developed his distinctive aesthetic in complete isolation. The quality of the prints and notation suggests that he regarded himself as a serious photographer although there is no evidence that he ever published or exhibited his work. A sole advert in Popular Gardening exists offering to photograph people’s gardens for half a crown, suggesting wider ambitions, yet whether anyone took him up on the offer we do not know. Jones’ grandchildren recall that, in old age, he used his own glass plates as cloches to protect his seedlings against frost – which may explain why no negatives have survived.

There is a spare quality and an uncluttered aesthetic in Jones’ images that permits them to appear contemporary a hundred years after they were taken, while the intense focus upon the minutiae of these specimens reveals both Jones’ close knowledge of his own produce and his pride as a gardener in recording his creations. Charles Jones’ sensibility, delighting in the bounty of nature and the beauty of plant forms, and fascinated with variance in growth, is one that any gardener or cook will appreciate.

Swede Green Top

Bean Runner

Stokesia Cyanea

Turnip Green Globe

Bean Longpod

Potato Midlothian Early

Pea Rival

Onion Brown Globe

Cucumber Ridge

Mangold Yellow Globe

Bean (Dwarf) Ne Plus Ultra

Mangold Red Tankard

Seedpods on the head of a Standard Rose

Ornamental Gourd

Bean Runner

Apple Gateshead Codlin

Captain Hayward

Larry’s Perfection

Pear Beurré Diel

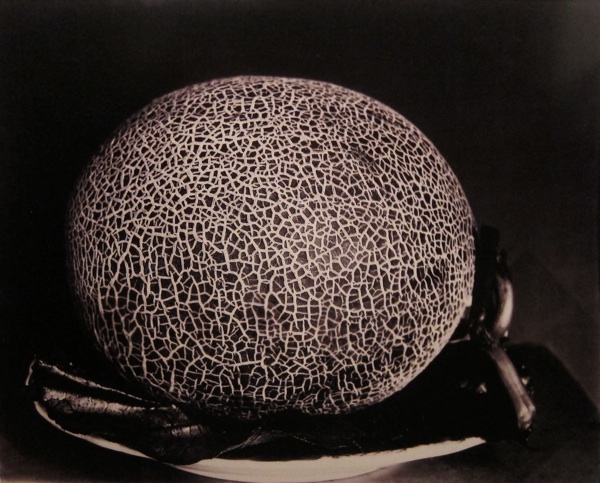

Melon Sutton’s Superlative

Mangold Green Top

Charles Harry Jones (1866-1959) c. 1904

The Plant Kingdoms of Charles Jones by Sean Sexton & Robert Flynn Johnson is published by Thames & Hudson

You might also like to read about

The Secret Gardens of Spitalfields

Thomas Fairchild, Gardener of Hoxton

Buying Vegetables for Leila’s Shop

Harold Burdekin’s London Night

Since the clocks went back an hour last night, the dusk will come more quickly each day now and I publish Harold Burdekin’s nocturnal photography of London as a celebration of darkness and the city

East End Riverside

As you will have realised by now, I am a night bird. In the mornings, I stumble around in a bleary-eyed stupor of incomprehension and in the afternoons I wince at the sun. But as darkness falls my brain begins to focus and, by the time others are heading to their beds, then I am growing alert and settling down to write.

Once I used to go on night rambles – to the railway stations to watch them loading the mail, to the markets to gawp at the hullabaloo and to Fleet St to see the newspaper trucks rolling out with the early editions. These days, such nocturnal excursions are rare unless for the sake of writing a story, yet I still feel the magnetic pull of the dark city streets beckoning, and so it was with a deep pleasure of recognition that I first gazed upon this magnificent series of inky photogravures of “London Night” by Harold Burdekin from 1934 in the Bishopsgate Library.

For many years, it was a subject of wonder for me – as I lay awake in the small hours – to puzzle over the notion of whether the colours which the eye perceives in the night might be rendered in paint. This mystery was resolved when I saw Rembrandt’s “Rest on the Flight into Egypt” in the National Gallery of Ireland, perhaps finest nightscape in Western art.

Almost from the beginning of the medium, night became a subject for photography with John Adams Whipple taking a daguerrotype of the moon through a telescope in 1839, but it was not until the invention of the dry plate negative process in the eighteen eighties that night photography really became possible. Alfred Stieglitz was the first to attempt this in New York in the eighteen nineties, producing atmospheric nocturnal scenes of the city streets under snow.

In Europe, night photography as an idiom in its own right begins with George Brassaï who depicted the sleazy after-hours life of the Paris streets, publishing “Paris de Nuit” in 1932. These pictures influenced British photographers Harold Burdekin and Bill Brandt, creating “London Night” in 1934 and “A Night in London” in 1938, respectively. Harold Burdekin’s work is almost unknown today, though his total eclipse by Bill Brandt may in part be explained by the fact that Burdekin was killed by a flying bomb in Reigate in 1944 and never survived to contribute to the post-war movement in photography.

More painterly and romantic than Brandt, Burdekin’s nightscapes propose an irresistibly soulful vision of the mythic city enfolded within an eternal indigo night. How I long to wander into the frame and lose myself in these ravishing blue nocturnes.

Black Raven Alley, Upper Thames St

Street Corner

Temple Gardens

London Docks

From Villiers St

General Post Office, King Edward St

Leicester Sq

Middle Temple Hall

Regent St

St Helen’s Place, Bishopsgate

George St, Strand

St Botolph’s and the City

St Bartholomew’s Hospital, Smithfield

Images courtesy © Bishopsgate Institute

You might like to read these other nocturnal stories

On Christmas Night in the City

Night at the Brick Lane Beigel Bakery

Night at The Spitalfields Market, 1991