Doreen Fletcher’s East End

Hairdresser, Ben Jonson Rd, 2001

It is my pleasure to publish this selection of the remarkable paintings and drawings created by Doreen Fletcher in the East End between 1983 and 2003, seen publicly for the very first time.

“I was discouraged by the lack of interest,” admitted Doreen to me plainly, explaining why she gave up after twenty years of doing this work. For the past decade, all these pictures have sat in Doreen’s attic until I persuaded her to take them out yesterday and let me photograph them for publication here.

Doreen came to the East End in 1983 from West London. “My marriage broke up and I met someone new who lived in Clemence St, E14,” she revealed, “it was like another world in those days.” Yet Doreen immediately warmed to her new home and felt inspired to paint. “I loved the light, it seemed so sharp and clear in the East End, and it reminded me of the working class streets in the Midlands where I grew up,” she confided to me, “It disturbed me to see these shops and pubs closing and being boarded up, so I thought, ‘I must make a record of this,’ and it gave me a purpose.”

For twenty years, Doreen conscientiously sent off transparencies of her pictures to galleries, magazines and competitions, only to receive universal rejection. As a consequence, she forsook her artwork entirely in 2003 and took a managerial job, and did no painting for the next ten years. But eventually, Doreen had enough of this too and has recently rediscovered her exceptional forgotten talent.

Many of Doreen’s pictures exist as the only record of places that have long gone and I publish her work today in the hope that she will now receive the recognition she deserves, not just for outstanding quality of her painting but also for her brave perseverance in pursuing her clear-eyed vision of the East End in spite of the lack of any interest or support.

Bartlett Park, 1990

Terminus Restaurant, 1984

Bus Stop, Mile End, 1983

Terrace in Commercial Rd under snow, 2003

Shops in Commercial Rd, 2003

Snow in Mile End Park, 1986

Laundrette, Ben Jonson Rd, 2001

The Lino Shop, 2001

Caird & Rayner Building, Commercial Rd, 2001

Rene’s Cafe, 1986

SS Robin, 1996

Benji’s Mile End, 1992

Railway Bridge, 1990

St Matthias Church, 1990

The Albion Pub, 1992

Turner’s Rd, 1998

The Condemned House, 1983

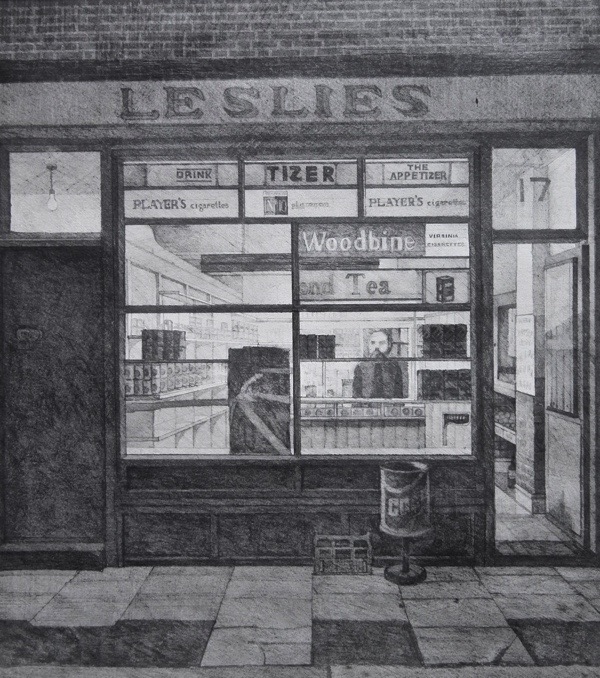

Leslie’s Grocer, Turner’s Rd, 1983 (Pencil Drawing)

Newsagents, Canning Town, 1991 (Coloured Crayon Drawing)

Bridge Wharf, 1984 (Pencil Drawing)

Pubali Cafe, Commercial Rd, 1990 (Coloured Crayon Drawing)

Ice Crean Van, 1990 (Coloured Crayon Drawing)

Images copyright © Doreen Fletcher

You may also like to take a look at

Ancient Graffiti At The Tower Of London

Now that tourists are scarce and the leaves begin to fall, it suits me to visit the Tower of London and study the graffiti. The austere stone structures of this ancient fortress by the river reassert their grim dignity in Autumn when the crowd-borne hubbub subsides, and quiet consideration of the sombre texts graven there becomes possible. Some are bold and graceful, others are spidery and maladroit, yet every one represents an attempt by their creators to renegotiate the nature of their existence. Many are by those who would otherwise be forgotten if they had not possessed a powerful need to record their being, unwilling to let themselves slide irrevocably into obscurity and be lost forever. For those faced with interminable days, painstaking carving in stone served to mark time, and to assert identity and belief. Every mark here is a testimony to the power of human will, and they speak across the ages as tokens of brave defiance and the refusal to be cowed by tyranny.

“The more affliction we endure for Christ in this world, the more glory we shall get with Christ in the world to come.” This inscription in Latin was carved above the chimney breast in the Beauchamp Tower by Philip Howard, Earl of Arundel in 1587. His father was executed in 1572 for treason and, in 1585, Howard was arrested and charged with being a Catholic, spending the rest of his life at the Tower where he died in 1595.

Sent to the Tower in 1560, Hew Draper was a Bristol innkeeper accused of sorcery. He pleaded not guilty yet set about carving this mysterious chart upon the wall of his cell in the Salt Tower with the inscription HEW DRAPER OF BRISTOW (Bristol) MADE THIS SPEER THE 30 DAYE OF MAYE, 1561. It is a zodiac wheel, with a plan of the days of the week and hours of the day to the right. Yet time was running out for Hew even as he carved this defiant piece of cosmology upon the wall of his cell, because he was noted as “verie sick” and it is low upon the wall, as if done by a man sitting on the floor.

The rebus of Thomas Abel. Chaplain to Katherine of Aragon, Abel took the Queen’s side against Henry VIII and refused to change his position when Henry married Anne Boleyn. Imprisoned in 1533, he wrote to Thomas Cromwell in 1537, “I have now been in close prison three years and a quarter come Easter,” and begged “to lie in some house upon the Green.”After five and half years imprisoned at the Tower, Abel was hung, drawn and quartered at Smithfield in 1540.

Both inscriptions, above and below, have been ascribed to Lady Jane Grey, yet it is more likely that she was not committed to a cell but confined within domestic quarters at the Tower, on account of her rank. These may be the result of nineteenth century whimsy.

JOHN DUDLE – YOU THAT THESE BEASTS DO WEL BEHOLD AND SE, MAY DEME WITH EASE WHEREFORE HERE MADE THEY BE, WITH BORDERS EKE WHEREIN (THERE MAY BE FOUND) 4 BROTHERS NAMES WHO LIST TO SERCHE THE GROUNDE. The flowers around the Dudley family arms represent the names of the four brothers who were imprisoned in the Tower between 1553-4 , as result of the attempt by their father to put Lady Jane Grey upon the throne. The roses are for Ambrose, carnations (known as gillyflowers) for Guildford, oak leaves for Robert – from robur, Latin for oak – and honeysuckle for Henry. All four were condemned as traitors in 1553, but after the execution of Guildford they were pardoned and released. John died ten days after release and Henry was killed at the seige of San Quentin in 1557 while Ambrose became Queen Elizabeth’s Master of the Ordinance and Robert became her favourite, granted the title of Earl of Leicester.

Edward Smalley was the servant of a Member of Parliament who was imprisoned for one month for non-payment of a fine for assault in 1576. Thomas Rooper, 1570, may have been a member of the Roper family into which Thomas More’s daughter married, believed to be enemies of Queen Elizabeth. Edward Cuffyn faced trial in 1568 accused of conspiracy against Elizabeth and passed out his days at the Tower.

BY TORTURE STRANGE MY TROUTH WAS TRIED YET OF MY LIBERTIE DENIED THEREFORE RESON HATH ME PERSWADYD PASYENS MUST BE YMB RASYD THOGH HARD FORTUN CHASYTH ME WYTH SMART YET PASEYNS SHALL PREVAIL – this anonymous incsription in the Bell Tower is one of several attributed to Thomas Miagh, an Irishman who was committed to the Tower in 1581 for leading rebellion against Elizabeth in his homeland.

This inscription signed Thomas Miagh 1581 is in the Beauchamp Tower. THOMAS MIAGH – WHICH LETH HERE THAT FAYNE WOLD FROM HENS BE GON BY TORTURE STRAUNGE MI TROUTH WAS TRYED YET OF MY LIBERTY DENIED. Never brought to trail, he was imprisoned until 1583, yet allowed “the liberty of the Tower” which meant he could move freely within the precincts.

Subjected to the manacles fourteen times in 1594, Jesuit priest Henry Walpole incised his name in the wall of the Beauchamp Tower and beneath he carved the names of St Peter and St Paul, along with Jerome, Ambrose, Augustine and Gregory – the four great doctors of the Eastern church.

JAMES TYPPING. STAND (OR BE WEL CONTENT) BEAR THY CROSS, FOR THOU ART (SWEET GOOD) CATHOLIC BUT NO WORSE AND FOR THAT CAUSE, THIS 3 YEAR SPACE, THOW HAS CONTINUED IN GREAT DISGRACE, YET WHAT HAPP WILL IT? I CANNOT TELL BUT BE DEATH. Arrested in 1586 as part of the Babington Conpiracy, Typping was tortured, yet later released in 1590 on agreeing to conform his religion. This inscription is in the Beauchamp Tower.

T. Salmon, 1622. Above his coat of arms, he scrawled, CLOSE PRISONER 32 WEEKS, 224 DAYS, 5376 HOURS. He is believed to have died in custody.

A second graffito by Giovanni Battista Castiglione, imprisoned in 1556 by Elizabeth’s sister, Mary, for plotting against her and later released.

Nothing is known of William Rame whose name is at the base of this inscription. BETTER IT IS TO BE IN THE HOUSE OF MOURNING THAN IN THE HOUSE OF BANQUETING. THE HEART OF THE WISE IS IN THE MOURNING HOUSE. IT IS MUCH BETTER TO HAVE SOME CHASTENING THAN TO HAVE OVERMUCH LIBERTY. THERE IS A TIME FOR ALL THINGS, A TIME TO BE BORN AND A TIME TO DIE, AND THE DAY OF DEATH IS BETTER THAN THE DAY OF BIRTH. THERE IS AN END TO ALL THINGS AND THE END OF A THING IS BETTER THAN THE BEGINNING, BE WISE AND PATIENT IN TROUBLE FOR WISDOM DEFENDETH AS WELL AS MONEY. USE WELL THE TIME OF PROSPERITY AND REMBER THE TIME OF MISFORTUNE – 25 APRIL 1559.

Ambrose Rookwood was one of the Gunpowder Plotters. He was arrested on 8th November 1606 and taken from the Tower on 27th January 1607 to Westminster Hall where he pleaded guilty. On 30th January, he was tied to a hurdle and dragged by horse from the Tower to Westminster before being hung, drawn and quartered with his fellow conspirators.

Photographs copyright © Historic Royal Palaces

You may also like to read about

At Maison Dellys, Columbia Rd

Farid Djebrouni

Maison Dellys is a small cafe in an old terrace beside the triangle of trees where Columbia Rd meets the Hackney Rd. In this quiet spot, you may rely upon a peaceful cup of tea and a snack at an affordable price – a commodity that grows increasingly scarce in this part of the East End. Farid Djebrouni opened his cafe eleven years ago and has worked hard to build up a significant clientele and reputation, but next week on Friday 30th October Maison Dellys will be closing forever in the face of a rent increase from £11,000 to £27,000 a year.

Rather than this event go unacknowledged, Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I went round for a chat with Farid this week to offer him our moral support and thank him for the invaluable service he has provided to the community over the last decade in creating a friendly focus for those who live and work locally.

“When I came here eleven years ago, I liked the look of this cafe with the big glass window and the trees outside. I was a nurse before I opened Maison Dellys. My father died when I was a child and I spent a lot of time around hospitals, so when I grew up I chose to become a nurse myself and take care of people. But after three years, I realised I wasn’t cut out for it and I had another love which was cooking so I decided to do this.

I was born in Nigeria and my wife and I used to live in Hackney, but then we moved to Barking because it was the closest we could afford to buy a place. My wife works for an investment bank in the City, she makes the money for them.

I get up each morning at five-fifteen. You get used to it but you have to be disciplined and go to bed early, which is difficult for me because I like to stay up late. I open every weekday from seven until four and I have one employee who works with me. I cook pasta and lasagna every day, one vegetarian and one meat. I make the sauces and bake the pastries first thing every day when I arrive. Sometimes, I have a line outside when I open at seven and its very busy between midday and two, but you don’t see anyone after three.

I like it very much although sometimes it can be a bit stressful when people are demanding. I look upon it as a challenge, to provide good food for people with nice service and make them comfortable. I recognise all my customers and know everyone by name, it’s like a small club. People feel at home. We get a wide range of customers who work nearby, from drug dealers to famous artists and architects, and they all mix together.

My landlord owns a shop round the corner too and their rent has gone up, so they increased mine from £11,000 to £27,000 a year. We tried to negotiate a new five year lease and they offered to come down to £25,000 a year. Nobody can afford to pay so much. Under my license, I only have limited hours and I can’t open at evenings or weekends.

In eleven years, I’ve seen the area change. When I came here there weren’t any coffee shops and Shoreditch High St was empty. The big boys are coming in now who will throw away £200,000 just have a presence in this area, and a lot of my customers who are designers and artists are moving out because they can’t afford the rent either.

I want to take a bit of time off until the of the year to clear my head and then I’ll look for a cafe further east in January. Otherwise, I’ll give up and try to get a job and become a Monday to Friday person. What I will miss will be the people I’ve met here. I’ve been fortunate, London is a great city but the people in the East End have the biggest heart.

I heard about the riot on Brick Lane and I don’t believe in violence but I understand why people are angry. So many are going out of business round here but the Mayor isn’t doing anything about it. It’s a bit scary.

I don’t try to be the best coffee shop in the world but it’s honest food at prices people can afford.”

A tall man with a sympathetic modest demeanour, Farid has become a widely-respected personality in this corner of Shoreditch in recent years. You have until next Friday 30th October to pay him a call and give Maison Dellys a bumper last week in business. There will be also be a party on Thursday 29th October from 5:30pm for regulars and well-wishers.

“I heard about the riot on Brick Lane and I don’t believe in violence but I understand why people are angry”

Jana Dushaj works alongside Farid at Maison Dellys

Farid Djebrouni – “I will miss the people I’ve met here”

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Visit MAISON DELLYS, 10 Columbia Rd, E2 7NN, until 30th October, 7am-4pm weekdays

You may also like to read about

So Long, Baldacci’s of Petticoat Lane

Charlie Caisey Of Billingsgate Market

You can hear my pal Charlie Caisey speak at the Billingsgate Market CHIT-CHAT on Wednesday 4th November as part of the CRIES OF LONDON season I have devised for Bishopsgate Insititute. Tickets are free but numbers are limited – click here to sign up

Eighty-five year old fishmonger Charlie Caisey retired more than twenty years ago yet he cannot keep away from the fish market for long, so I was delighted to give him an excuse for a nocturnal visit – showing me around and introducing me to his pals. These days, Charlie maintains his relationship with the fish business through involvement with the school at Billingsgate, where he teaches young people training as fishmongers and welcomes school parties visiting to learn about fish.

Universally respected for his personal integrity and generosity of spirit, Charlie turned out to be the ideal guide to the fish market. Thanks to him, I had the opportunity to shake the hand and take the portraits of many of Billingsgate’s most celebrated characters, and now that he can look back with impunity upon his sixty years of experience in the business, Charlie told me his story candidly. He did not always enjoy the high regard that he enjoys today, Charlie forged his reputation in an arena fraught with moral challenges.

“In 1950, when I joined Macfisheries and started in a shop at Ilford, I was told, “You’ll never make a fishmonger,” and they moved me to another shop in Leytonstone. I was honest and in those days fishmongers always added coppers to the scale but I wouldn’t do that. Later, when I ran my shop, it was always sixteen ounces to the pound.

In Leytonstone, it was an open-fronted shop with sawdust on the floor. You had a blocksman who did the fishmongering, a frontsman who served the customers and a boy who ran around. At twenty-one, I was a boy fishmonger and then the frontsman decided to leave, so I moved up when he left. And I found I had an uncanny ability at arranging fish in shows! I made quite a little progress there, even though I was never taught – just three weeks at Macfisheries’ school.

I got my first management of a fish shop within three years, I was sent out to a poor LCC estate at Hainault. It was a fabulous shop but it was losing money, this was where I learnt to run a business and I worked up a bit of a storm there, working eighty hours a week and accounting the stock to a farthing. As a consequence, I was offered a first hand job in a shop behind Selfridges where all the customers were lords and ladies, but I refused because, if I was manager in my own shop, it would have been a step down. So then they sent me to run a shop in Bayswater. It was a lovely shop, when I arrived I had never seen many of the fish that were on display there, and I became wrapped up in it. We had a great cosmopolitan public including ladies of the oldest profession in the world.

Within a couple of years, Macfisheries moved me to Notting Hill Gate at the top of Holland Park Avenue – absolutely fabulous. I served most of the embassies and the early stars of television. The likes of Max Wall, Dickie Henderson and the scriptwriter of The Good Life were customers of mine. I built up quite a reputation and I was the first London manager to earn £1000 a year. From there I went to Knightsbridge running the largest fish shop in London, opposite Harrods. In 1965, I had thirty-five staff working under me and I worked fourteen hours a day.

My dream was to go into business on my own but I had no money. When I started my own shop, the sad part was how poor it was. It had holes in the floor, no proper drainage and no refrigeration. I’d never been to Billingsgate Market in my thirteen years at Macfisheries and when I went with my small orders, it was a different ball game. The dealers treated me like an idiot, the odd shilling was going on the prices and I was given short measures. Yet I never took it personally and I started to earn their respect because I always paid my bills every week. And, in twenty years, my turnover went from twelve thousand pounds to over half a million a year.

Most of my experience and knowledge has come from the customers. My experience of life came from the other side of the counter. They showed me that if you go out and look, there is a better life. When I think of Stratford while I was growing up, it was a stinky place because of the smell from the soap factories. My family were all railway people, my father was an uneducated labourer and what that man used to do for such a small amount of money and bad working conditions. We were poor because my marvellous parents were underpaid for their labours. I didn’t leave London during the war and I witnessed all the horrors. I missed lots of school because I was in the East End all through the bombing, so I’ve always been conscious of my poor education. Basically, I’m a shy man and I’m always amazed that I can stand up in front of people and speak, but I can do it because it comes from the heart.

Don’t ever do what I did. I went eighteen years without a holiday. It was a little crazy, I was forty before I had time to learn to drive.”

Dawn came up as Charlie told me his story and we walked out to the back of the fish market where the dealers throw fish to the seals from the wharf. Through his tenacity, Charlie proved his virtue as a human being and won respect as a fishmonger too. Yet although he may regret the inordinate struggle and hard work that kept him away from his family growing up, Charlie is still in thrall to his lifelong passion for this age-old endeavour of distributing and selling the strange harvest of the deep.

Clearing away after a night’s trading at Billingsgate, 7:40am.

Tom Burchell, forty-nine years in the fish business.

Alan Cook, lobster specialist for fifty-two years.

Simon Chilcott, twenty-four years at Bard Shellfish.

Mick Jenn, fifty-four years in eels – “Me dad was an empty boy and I started off in an eel factory.”

Terry Howard, sixty-three years in shellfish – “I played football in the 1960 Olympics.”

Anwar Kureeman, twelve years at Billingsgate – “I am a newcomer.”

Paul Webber, seventeen years at J.Bennett, Billingsgate’s largest salmon dealers.

Andres Slips came from Lithuania eleven years ago – “I couldn’t speak English when I arrived, now my mother would blush to hear my language.”

Geoff Steadman, fourth generation fish dealer, thirty-three years at Chamberlain & Thelwell.

Charlie in his first suit at fifteen –“From Willoughbys, I paid for it myself at half a crown a week.”

Charlie at the Macfisheries School of Fishmongery (He is third from right in back row).

Charlie in his fish shop in the seventies.

Charlie Caisey – the little fish that became a big fish.

You may recall I met Charlie Caisey at The Fish Harvest Festival

You may also like to take a look at

Boiling the Eels at Barney’s Seafood

Charles Booth’s East End Revisited

Photographer Keith Greenough has taken this series of pictures entitled LIFTING THE CURTAIN, complemented with texts by Charles Booth from his Life & Labour of the People 1889, as a means to explore the presence of the past in the East End. You can see the complete series of photographs in an exhibition at Townhouse, Fournier St, Spitalfields until Sunday 25th October.

Andrews Rd – “Neighbourhood of the gasworks accounts for what roughness there is … pistol-gangs of boys aged fourteen – seventeen. A girl was wounded and the sentences passed very heavy. Since then there has been no trouble.”

Bethnal Green Rd – “The workers of the district are cabinet makers who drink – glass blowers who drink – and costers who drink – They make good enough money but none of them spend it well!”

Bow Rd – “the ‘factory girl’ generally earns from seven shillings to eleven shillings – rarely more … Sunday afternoons she will be found promenading up and down the Bow Rd, arm in arm with two or three other girls”

Cremer St – “he complained of the great pressure put upon the police by publicans, also of pressure by the police on the police not to give up a source of revenue. Very little beer is now given … money has taken its place.”

Hanbury St – “And this living and working in one room intensifies the evil … here it is overcrowding day and night – no ventilation to the room, no change to the worker.”

Isle of Dogs – “Poplar, a huge district that includes the Isle of Dogs – transformed now into an Isle of Docks. In all it is a vast township, built on low marshy land, bounded by a great bend in the Thames.”

Jerome St – “Our attention is arrested by the fact that all work in the trade is carried on in factories. Women cigar makers get from fifteen to forty per cent less wages than men … some of them, however, when very quick with their fingers get as much as one pound a week.”

Leman St – “In the inner ring, nearly all available space is used for building and almost every house is filled up with families. The building of large blocks only substitutes one sort of crowding for another.”

Pitfield St – “The East End theatregoer even finds his way westwards and in the sixpenny seats of the little house in Pitfield St I have heard a discussion on Irving’s representation of Faust at the Lyceum.”

Tower Hamlets Mission – “the Great Assembly Hall Mission, Mile End Rd, is carrying on extensive work and draws several thousands of people to its religious services.”

Wentworth St – “… strange sights, strange sounds and strange smells. Streets crowded so as to be thoroughfares no longer … Petticoat Lane is the exchange of the Jew but the lounge of the Christian.”

Whitechapel High St – “clearances and rebuilding cause a far greater disturbance of population. The model blocks do not provide for the actual displaced population, so much as for an equivalent number of others, sometimes of a different class.”

Photographs copyright © Keith Greenough

You might also like to take a look at

The Ravenous Appetite Of Mr Pussy

I have rarely had an uninterrupted night’s sleep recently. Although characteristically a mild and sedentary personality by day, my old cat – Mr Pussy – transforms at night into an insistent creature of voracious appetite, waking me from my slumber to demand I feed him with a nocturnal snack. I tried shutting the bedroom door but he screamed so long and so loud, he woke up the neighbours. I have no choice but to take the path of least resistance and fill up his dish, if I am to have any sleep at all.

Mr Pussy is fourteen years old and I did fear that there could be some sinister emerging affliction which might provoke this rapacious conduct. Old cats can be susceptible to thyroid problems, I read, and the symptoms including ravenous hunger and volatile behaviour. So – reluctantly – I took him to the veterinary surgeon last week for expensive blood tests which might discover any underlying problems, and came back with a test tube to collect a urine sample.

Just six months ago, Mr Pussy had serious dental work to remove several rotten teeth which led him to forsake the biscuits that, like an eighteenth century mariner, have been his staple diet until this year. Consequently, he has discovered a whole new appetite and has no scruple about asserting his right as a member of the household to participate in every meal, preferring human food to anything produced for cats. No longer able to hunt for prey, nowadays he eats kitchen scraps supplemented with raw meat and sardines.

When I returned home from the vet and released Mr Pussy from his basket, the challenge of obtaining a feline urine sample dawned. Dutifully I tipped the non-absorbent granules I had been supplied into a litter tray and locked the cat flap, on the principle that once Mr Pussy did his business, I could syringe it up into the test tube. Yet this was not be, instead he paced around with increasing anxiety, taking no interest in the litter tray and seeking a likely location as a last resort for when the pressure grew too much.

Tactfully, Mr Pussy chose the corner of the bedroom where the shoes are lined up as the smelliest spot in the house where his misdemeanour might be least noticed and, after enduring his vocal frustration for several hours, I was delighted when he squatted down beside my boots to relieve himself on the floor. “That’s very professional,” gasped the receptionist at the veterinary surgery when I delivered the test tube promptly, suggesting that I was perhaps not alone in my struggle with this particular task.

Once I had accommodated to the painful realisation that Mr Pussy’s recent nocturnal behaviour might signal the commencement of his terminal decline, I received the call from the vet to inform me that all the tests revealed he was in exceptionally good health for a cat of his age. He was a little underweight, I was told. The dry biscuits he had forsaken were high protein and Mr Pussy is a large cat, so he needs to eat a significantly higher volume of other food to compensate.

The explanation was unavoidably simple. Mr Pussy woke me in the night because he had a ravenous appetite and I fed him too little. Now I leave him a generous late supper before I take to my bed and, thankfully, nocturnal dramas have relented. We can all sleep peacefully in this corner of Spitalfields again.

You may also like to read

Nicholas Borden’s Solo Show

Nicholas’ first major solo show is at Millinery Works in Islington from today until November 15th

Princelet St

Ever since I came upon Nicholas Borden working at his easel in the snow on Vallance Rd in Bethnal Green a few years ago, I have been captivated by his painting. In a quietly subversive way, Nicholas has created his own distinctive way of viewing the city that entirely re-invents urban landscape painting. Sensitive to the spirit of place yet equally alive to the abstract and colourist potential of his subjects, his pictures possess a freshness of vision that is as unique as it is unexpected. Hardened by his years as a freshwater fisherman, he is curiously impervious to the English weather and you know that – like Joseph Mallord Turner or John Constable before him – each of these paintings is the outcome of a battle with the elements that Nicholas Borden won.

Fleur de Lys St

Middlesex St

Spitalfields from Petticoat Lane

Shoreditch High St

Durant St, Bethnal Green

Regents Canal

Wilton Way, Hackney

At the Royal Exchange

Queen Victoria St

Charing Cross Station

Charing Cross Rd

Shaftesbury Ave

In Cambridge Circus

Paintings copyright © Nicholas Borden

You may like to take a look at more of Nicholas Borden’s work

Nicholas Borden’s East End View

Nicholas Borden’s Winter Paintings