Paul Gardner’s Collection

You will recall that I have written about Paul Gardner, the fourth generation paper bag seller, quite a few times in these pages. Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen is the longest established family business in Spitalfields, trading in the same building for one hundred and forty years, and acquiring a unique assembly of heirlooms.

So I visited Paul’s shop at 149 Commercial St to photograph this collection of artefacts which have accumulated there since his great-grandfather James Gardner first opened in 1870, trading as scalemakers. We took down some things from the walls and photographed them on the floor, we arranged other items on the worn counter-top and I stood upon Paul’s chair to take my pictures. Both Paul and his customers were extremely gracious, continuing their transactions and buying their bags as usual, politely disregarding the mayhem.

Paul told me that if he were a paper bag, he would be a brown paper bag because they are his bestsellers – multi-purpose bags, and the ones he has made most money out of over the years. So it is entirely appropriate that when Spitalfields Life Contributing Artist Lucinda Rogers drew her portrait of Paul in his shop a few years back, she drew it on brown paper. Now it hangs in pride of place high up on the wall behind the counter.

Coming upon the artefacts pictured below in a museum would be intriguing but not surprising. In a museum they would be removed from life and arranged. But the only arrangement you see below was created for these photos. Discovering these items still remaining in the working place where they belong is enthralling in a different way. In Paul’s shop they retain their full functional quality as objects that were once in use here (the coin tray and Oxo tin are still in use), acquiring dditional meaning as mementos of the three antecedents who pursued the same trade in this place where Paul works today. Quite simply, these are the things that James, Bertie and Roy left behind, and their presence lingers in these everyday possessions as evidence of their working lives and evocations of the world they knew. Today, Paul is his predecessors’ representative and the custodian of their stuff. Yet I do not think Paul thinks twice about his wooden coin tray that is worn by four generations of use, unless someone points it out to him.

Paul has a fine collection of greengrocer’s labels specifying varieties of apples and pears – Comice, Ripe Williams, Dunn’s Seedlings, Choice Worcesters and Ellison’s Orange, names as lyrical as a Betjeman verse. Equally, there is a powerful magic to the simple phrase ‘morning gathered’ evoking images of dawn in the orchards, though I do wonder what kind of customer could be enticed by the pale allure of ‘Worthing grown.’

Most fascinating to me is the Day Book begun by James Gardner on 1st January 1892 with bold calligraphic flourishes. James used this sturdy book with fine marbled endpapers to record all the different East End greengrocers where he serviced the scales on a regular basis. James’ elegant italic hand can readily be deciphered to read many familiar addresses in Spitalfields. It is remarkable that he could maintain such poised handwriting when you consider how many customers James visited in a single day, though as business increased through the life of this ledger, his handwriting becomes hastier and more excited.

There was so much more – including the family bible ‘Won by the Bugler James Gardner of the 1st Tower Hamlets rifle Brigade for shooting. Presented by Lady Jane Taylor, December 21st 1882,’ with the entire family tree over five generations (revealing James’ year of birth as 1847 and his origin as Thaxted in Essex), the catalogues of scales, the insurance certificates, various family military cards from the different wars, and the modern receipt books with their blue carbon pages that end in 1968 on the day Paul’s father Roy Gardner died – all the pamphlets and pieces of paper that add up to four generations of trading for Gardners.

I do not want to see Paul Gardner’s collection in a museum, I want to see it stay where it belongs in his shop, scattered among all the different stacks of coloured paper bags, and hidden among the tapes and tags, to be discovered on shelves and racks, behind the modest green facade of the most celebrated business in Commercial St.

Roy Gardner stands outside Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen in the nineteen forties – note the sales tickets on display inside the shop.

Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen, 149 Commercial St, London E1 6BJ (6:30am – 2:30pm, Monday to Friday)

You may like to read these other stories about Gardners Market Sundriesmen

Paul Gardner, Paper Bag Seller

At Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen

Joan Rose at Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen

At The Clerkenwell Sessions House

Anyone who knows Clerkenwell knows the old sessions house which dominates the western side of the green, yet few have ever been inside. Built around 1780, it is mostly remembered as the location of Charles Dickens’ early employment as a cub reporter, reporting on court cases. Subsequently, he wove the location into his novels and this where Oliver Twist was tried after being caught stealing a pocket watch on Clerkenwell Green.

Joseph Merceron, the corrupt magistrate and gangster, known as the Boss of Bethnal Green once held court here, sentencing those who displeased him to Cold Bath Sq prison, a mile to the north.

Yet the sessions house was closed for judicial use nearly a century ago and has been the headquarters of a scalemaker and a masonic hall, permitting only few visitors and thus – all this time – it has stood in Clerkenwell as an enigma that could not be explored. For at least thirty years, I have walked past and wondered about what might lie inside before I entered through the front door last week to encounter its spectacular interior, with a dome modelled after the Pantheon, reborn in its full glory following a comprehensive four-year renovation.

At the centre of the sessions house is a magnificent hall containing a staircase ascending to the first floor with a vast opalescent glass screen and a gallery that enfolds the space, beneath the dome towering overhead. The building is oriented upon an east-west axis and you discover yourself inside a huge light box, with rays of sunlight refracting, bouncing and playing upon all the surfaces. Removal of twentieth and late nineteenth century architectural interventions have reinstated the austere classicism of this interior with thrilling results.

From here, I set out to explore the side rooms by means of the myriad hidden staircases that lead to the upper and lower floors. Whereas the central hall has been repainted in its original stone and old-white tones, the secondary spaces retain the attractive patina of ages prior to any redecoration that future tenants may enact. Despite the logic of the central hall, these staircases create the feeling of a warren, linking unexpected spaces – so that you may equally discover yourself in the magistrates dining room or the holding cells. While the atmosphere of institutionalised violence enacted in the name of the judiciary by Joseph Merceron and others has been dispelled from the public spaces, it is inescapable in the basement where the arrangement of cells is apparent and the nature of confinement is palpable. It will be a sobering thought for the customers of the bars and wine vaults that are planned for these spaces.

Quite soon, the Clerkenwell Sessions House will be filled with people again and restored to life as a place for meetings and transactions both business and social. Yet at this moment, as the restoration draws to completion and the grand rooms sit empty, it enjoys a short-lived adjournment inhabited only by the ghosts of former days.

The dome modelled after the Pantheon

The opalescent screen

Staircase for magistrates

Staircase for service

Staircase for prisoners ascending to the dock

Passageway between the former cells in the basement

The basement

Spire of St James Clerkenwell and the dome of the Session House

Looking west along Clerkenwell Rd

Looking north up Farringdon Lane

The door onto Clerkenwell Rd

The sessions house drawn by Augustus Pugin and Thomas Rowlandson, 1806

Visit THE OLD SESSIONS HOUSE on Clerkenwell Green

You may also like to take a look at

William Henry Knapp’s Memoir

Jeanette Crawley sent me her transcript of ten pages of a memoir written in 1935 by her great-grandfather William Henry Knapp (1872-1952), describing his early life working in the City of London for a Provisions Merchant at the end of the nineteenth century, of which it is my pleasure to publish these extracts today.

You might assume that the work of a City delivery boy was mundane, yet William delivered breakfasts to condemned prisoners at Newgate, tangled with Secret Service agents and attended executions. ‘Every day was of interest,’ he concluded retrospectively.

William Henry Knapp

I first saw the light on the 27th July 1872 at 73 Carter Lane, London EC2, formerly Shoemakers Row. My father was employed at the above address for forty-five years in the manufacture of tobacco etc and was resident for thirty-two years past, at the place where I grew and noted the ever-changing aspect of the City proper.

At that time, cabs plied for hire and buses made their regular call at such places as the Mansion House and other notable buildings. I also well remember the extra horse ridden by a boy to help pull the bus up Ludgate Hill – what a contrast to the present day.

I attended the local infant school and rose by gradual stages until it was time for lessons on a higher plane and I graduated to St Thomas Charterhouse, a school of sound teaching and hard and fast rules. I see today in my mind’s eye – fifty-four years after – the urbane and full-bearded headmaster, Mr Smith, who in turn was well supported by most efficient class masters Mr Wallace, Mr Cose etc. who were there to teach and no nonsense. I also well remember that a cane was provided but never shared. In my day, recreation consisted of just the bank holiday and two weeks in the summer – what a contrast. As regards the education then and now – well, I will not give it a voice but just think it.

Home life was very regimented and, as I see things today, distinctly correct and helpful to shaping of the lives, creating and fitting us as men and women for the life to be. Parents were eminent and ruled as parents should.

During my school days many great events happened. The Tay Bridge disaster, the Nile expedition, Boer War and later the African War, etc. etc. All very terrible in their way and I well remember seeing the return of some of the guards who fought in their regimentals in those days and were bespattered with blood and dust. In spite of leaving, still the war game goes on.

Now I get along to the age of fourteen years, the usual time for launching out to get one’s own living. I well remember, after a domestic episode in which my father and myself were the chief factors, he giving his dictum that I must find work inside two days or go back to school and, as I preferred the former, I got going and obtained a situation in a house which I served truly and well for over five years.

I can visualise the employer – my ideal of a real man – questioning me as to my own ability for work. Among the questions put was how much can you carry? So, sticking out my chest, I answered ‘Three quarters of a hundredweight, Sir,’ and from that day onward, during my junior capacity, I was well loaded each time I went delivering.

I would point out that we had no trollies, trucks or tricycles, but just a tray containing goods on which I carried the weight of which often totalled a hundredweight and had to be delivered in rotation to the numerous customers. The title of the firm was Sherwood & Vesper Provision Merchants, 45 Ludgate Hill, London EC2, that was controlled by George Beach Newman and to him I owe my knowledge of the Provision Trade.

My start in life was eight shillings per week for thirteen hours a day, and I recall my father’s question, ‘Where are your wages?’ I proudly placed same in front of him. He then decided that I would hand four shillings to my mother, place two shillings and sixpence in the bank and retain one shilling and sixpence for myself and buy my own clothes – what a proposition for a youth of today.

One of the duties, during my first years, was to take in the last breakfast of the condemned in Newgate Prison. That came about by the fact that we served the celebrated firm of Ring Brymer, the City Caterers, and through them it became my duty to deliver such necessaries.

During the five years with my first firm, many incidents occurred that have been imprinted on my mind, such men as Alderman Treelawn, Sir John Bennett and local characters like W. Straken, the Ludgate Hill Stationers, the sons of the latter were in everyday touch with me and his daughters had a smile for me. For, behold, I was by that time junior clerk and cashier and, as such, received the esteem of the above.

Leading up to those years was the memory of the Phoenix Park Murders and, after the trial, the chief culprit Brady and others were executed at Newgate. Carey the informer was acquitted, receiving a free pardon and I believe a solatium from the British government and free passage to Australia. A destination he failed to reach because he was followed on board the vessel and shot by a man named O’Donnell who was brought back to England and executed at Newgate. As a small boy at that time, I remember among the crowd outside was brother of O’Donnell who, when the black flag went up, excitedly shouted, ‘My brother died bravely’ and, but for the police protection, would have been roughly handled.

Ireland was a mass of trouble in those days and their next actions to voice their demand for Home Rule was the deputing of members of their secret Clan to blow up many important and Public buildings in and about London with dynamite. I well remember many members of the Clan were captured in a house in Nelson Sq, Blackfriars Rd, but, from that time and onwards, there was a reign of terrorism which put the authorities at their wits end.

And, while touching on this subject, I now come to the time when I, in the capacity of junior clerk at Ludgate Hill, was the unconscious messenger and bearer of news of great portent as between the celebrated Secret Service agent Major Le Caron and the British government. The Major was the chief of the Fenian organisation on the American side and his good work between the two countries helped in a large degree to stamp out the Fenian menace. But, from the time of his leaving America for England, he went in daily fear of his life and was guarded wherever he went, and what he could not openly do, I did through my employer Mr Newman.

The connection of the aforesaid was – as under my employ – my employer’s name was George Beach Newman, Le Caron’s real name was William Beach and they in turn were the cousins of the celebrated Jam Manufacturers T.W.Beach. So you see, by their aid, Le Baron was able to distribute his knowledge and not forced to be his own messenger.

His career as Secret Service man was very valuable and I had grown into manhood when next I saw him, by chance, seated in a carriage on his way to Hastings which also was my destination. I did hear, just a few years afterwards, of his death and, as his age was somewhere in his fifties, he died comparatively a young man.

My first working years were very interesting as well as being hard-working and, as a man today beyond the sixty mark, I can think of the romance attached to my first job necessitating my calling at some of the most important buildings, firms and institutions in the City. Some are demolished or out of date but just a few remain and I can recount from memory a few of the places and firms.

My old firm was on Ludgate Hill, next St Martin’s Court, which is bordered on one side by the well known City Stationers, W. Straken. While I have him in mind, I must tell you that his first start in life was sitting in a small window in the left hand corner of St Paul’s Church and printing visiting cards at so much per hundred while you wait. In his case, one can quote the old adage, ‘nothing succeeds like success.’ What a character he was, good features, curly grey hair, immaculately dressed. If he ever wore a hat, it was of the sombrero type worn at a rakish angle, with a silk coat, plush waistcoat and very pronounced black and white check trousers. In his spare time, on bright days, he would parade the pavement near or about his premises and people naturally asked, ‘Who’s that?’ He was a city character once seen could never be forgotten.

At the extreme end of St Martin’s Court stood what we boys called the old London Wall – a mass about forty feet by ten and possibly the position of the ancient Lud Gate, one of the many gates protecting the City. I well remember with the tools of those days it took considerable time to demolish it.

Harking back to my birthplace, the room above the factory in which I was born, stood on the old site of Blackfriars Priory and close handy was also the Church of St Anne’s Blackfriars, destroyed in the Great Fire of London but never rebuilt, where is a grand playhouse to this day and, upon that site, stood Shakespeare’s Blackfriars Theatre. All that remains today of that particular site is the Old Apothecaries Hall, where I have seen the giant spit support a whole Bullock.

My early work took me to the halls of all the great City companies and I was always impressed by their stately grandeur, and many a tasty morsel has come the way of yours truly – for my work took me right into the kitchens to see his highness the Chef, who reigned supreme in all matters pertaining to food.

When the factory buildings adjacent were demolished, the workers came across the old foundations of the priory and many interesting finds were made including some thousands of arm and leg bones and skulls. I think it was conjectured at the time that there were remains of old Friars or a collection of remains from the Great Fire.

We now retrace to Ludgate Circus where stands the King Lud public house, very famous in its day. On the opposite side, Q.Dells the Phrenologist who placated his windows with leaflets on his knowledge of the human brain and was also another of the City’s characters.

My firm found every public house of note to Temple Bar and – possibly the best house of all still remains – The Old Cheddar Cheese, in those days run by another notability, Beauford Moore. I had the honour of delivering the real Cheshire Cheese that stood on the public house bar for all and Sundry to taste.

In Cornhill stood the firm of Ring & Brymer, the most noted of all City Caterers, where Turtle Soup was made from real turtles. I have seen them myself delivered by the vanload and no other firm at that time knew better how to serve up and prepare a banquet than they. When I review those days bygone – what an account – one regular order alone was forty pounds of Harris’s bladders of lard and, during the year, an order for two hundred and fifty York Hams and always ten special hams for the Lord Mayor’s Banquet.

Their weekly order averaged about fifty pounds, payable every Friday morning. This would make the mouths water of tradesmen today. At that time, the Mansion House used to have its own kitchen and staff. The chef was supreme, his name sounded to us like ‘Shrubshole.’ The housekeeper on many occasions handed me some titbit with a kindly, ‘Would you like this, sonny?’ and sonny did, you bet!

There is one more episode of my early days on Ludgate Hill and that was the coming to my old firm – just before Christmas time – of fine grand elderly gentlemen who were the principals of Courage’s, the Brewers which at that time was termed ‘Tomkins, Courage Cracknel & Co.’ Those five gents used to select and taste from two hundred and fifty to three hundred Stilton Cheeses to give away as Christmas presents. Each and every one of them had to be packed there and then, under their watchful eye, and labelled to Mr or Mr so-and-so. There they sat around an improvised table, tasting cheese, drinking some celebrated Courage’s Stout and munching Bath Water Biscuits. A sight for the Gods, and I doubt if it will ever occur again in the Provision Trade. These reminiscences are as good as a tonic to me. In spite of hard work and long hours, every day was of interest.

Photographs of Ludgate Hill courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute

Charles Jones, Photographer

Garden scene with photographer’s cloth backdrop c.1900

These beautiful photographs are all that exist to speak of the life of Charles Jones. Very little is known of the events and tenor of his existence, and even the survival of these pictures was left to chance, but now they ensure him posthumous status as one of the great plant photographers. When he died in Lincolnshire in 1959, aged 92, without claiming his pension for many years and in a house without running water or electricity, almost no-one was aware that he was a photographer. And he would be completely forgotten now, if not for the fortuitous discovery made twenty-two years later at Bermondsey Market, of a box of hundreds of his golden-toned gelatin silver prints made from glass plate negatives.

Born in 1866 in Wolverhampton, Jones was an exceptionally gifted professional gardener who worked upon several private estates, most notably Ote Hall near Burgess Hill in Sussex, where his talent received the attention of The Gardener’s Chronicle of 20th September 1905.

“The present gardener, Charles Jones, has had a large share in the modelling of the gardens as they now appear, for on all sides can be seen evidence of his work in the making of flowerbeds and borders and in the planting of fruit trees. Mr Jones is quite an enthusiastic fruit grower and his delight in his well-trained trees was readily apparent…. The lack of extensive glasshouses is no deterrent to Mr Jones in producing supplies of choice fruit and flowers… By the help of wind screens, he has converted warm nooks into suitable places for the growing of tender subjects and with the aid of a few unheated frames produces a goodly supply. Thus is the resourcefulness of the ingenious gardener who has not an unlimited supply of the best appurtenances seen.”

The mystery is how Jones produced such a huge body of photography and developed his distinctive aesthetic in complete isolation. The quality of the prints and notation suggests that he regarded himself as a serious photographer although there is no evidence that he ever published or exhibited his work. A sole advert in Popular Gardening exists offering to photograph people’s gardens for half a crown, suggesting wider ambitions, yet whether anyone took him up on the offer we do not know. Jones’ grandchildren recall that, in old age, he used his own glass plates as cloches to protect his seedlings against frost – which may explain why no negatives have survived.

There is a spare quality and an uncluttered aesthetic in Jones’ images that permits them to appear contemporary a hundred years after they were taken, while the intense focus upon the minutiae of these specimens reveals both Jones’ close knowledge of his own produce and his pride as a gardener in recording his creations. Charles Jones’ sensibility, delighting in the bounty of nature and the beauty of plant forms, and fascinated with variance in growth, is one that any gardener or cook will appreciate.

Swede Green Top

Bean Runner

Stokesia Cyanea

Turnip Green Globe

Bean Longpod

Potato Midlothian Early

Pea Rival

Onion Brown Globe

Cucumber Ridge

Mangold Yellow Globe

Bean (Dwarf) Ne Plus Ultra

Mangold Red Tankard

Seedpods on the head of a Standard Rose

Ornamental Gourd

Bean Runner

Apple Gateshead Codlin

Captain Hayward

Larry’s Perfection

Pear Beurré Diel

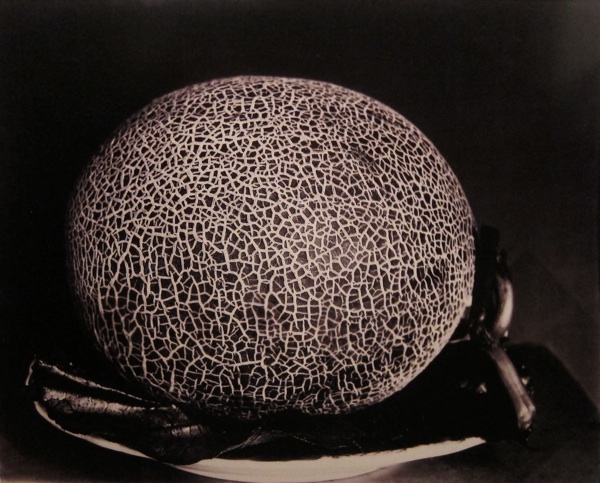

Melon Sutton’s Superlative

Mangold Green Top

Charles Harry Jones (1866-1959) c. 1904

The Plant Kingdoms of Charles Jones by Sean Sexton & Robert Flynn Johnson is published by Thames & Hudson

You might also like to read about

The Secret Gardens of Spitalfields

Thomas Fairchild, Gardener of Hoxton

Buying Vegetables for Leila’s Shop

High Days & Holidays Of Old London

With another Bank Holiday imminent, it is time for us to consider high days & holidays of old London

Boys lining up at The Oval, c.1930

School is out. Work is out. All of London is on the lam. Everyone is on the streets. Everyone is in the parks. What is going on? Is it a jamboree? Is it a wingding? Is it a shindig? Is it a bevy? Is it a bash?

These are the high days and holidays of old London, as recorded on glass slides by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society and once used for magic lantern shows at the Bishopsgate Institute.

No doubt these lectures had an educational purpose, elucidating the remote origins of London’s quaint old ceremonies. No doubt they had a patriotic purpose to encourage wonder and sentiment at the marvel of royal pageantry. Yet the simple truth is that Londoners – in common with the rest of humanity – are always eager for novelty, entertainment and spectacle, always seeking any excuse to have fun. And London is a city ripe with all kinds of opportunities for amusement, as illustrated by these magnificent photographs of its citizens at play.

Are you ready? Are you togged up? Did you brush your hair? Did you polish your shoes? There is no time to lose. We need the make the most of our high days and holidays. And we need to get there before the parade passes by.

At Hampstead Heath, c.1910.

Walls Ice Cream vendor, c.1920.

At Hampstead Heath, c.1910.

At Hampstead Heath, c.1910.

Balloon ascent at Crystal Palace, Sydenham, c.1930.

At the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens, 1896.

Christ’s Hospital Procession across bridge on St Matthews Day, 1936.

A cycle excursion to The Spotted Dog in West Ham, 1930.

Pancake Greaze at Westminster School on Shrove Tuesday, c.1910.

Variety at the Shepherds Bush Empire, c.1920.

Dignitaries visit the Chelsea Royal Hospital, c.1920.

Games at the Foundling Hospital, Bloomsbury, c.1920.

Riders in Rotten Row, Hyde Park, c.1910.

Physiotherapy at a Sanatorium, 1916.

Vintners’ Company, Master’s Installation procession, City of London, c.1920.

Boating on the lake in Battersea Park, c.1920.

The King’s Coach, c.1911.

Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession, 1897.

Lord Mayor’s Procession passing St Paul’s, 1933.

Policemen gives directions to ladies at the coronation of Edward VII, 1902.

After the procession for the coronation of George V, c.1911.

Observance of the feast of Charles I at Church of St. Andrew-by-the-Wardrobe, 1932.

Chief Yeoman Warder oversees the Beating of the Bounds at the Tower of London, 1920.

Schoolchildren Beating the Bounds at the Tower of London, 1920.

A cycle excursion to Chingford Old Church, c.1910.

Litterbugs at Hampstead Heath, c.1930.

The Foundling Hospital Anti-Litter Band, c.1930.

Distribution of sixpences to widows at St Bartholomew the Great on Good Friday, c.1920.

Visiting the Cast Court to see Trajan’s Column at the Victoria & Albert Museum, c.1920.

A trip from Chelsea Pier, c.1910.

Doggett’s Coat & Badge Race, c.1920.

Feeding pigeons outside St Paul’s, c.1910.

Building the Great Wheel, Earls Court, c.1910.

Glass slides copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

The Map Of Industrious Shoreditch

Each Saturday, we shall be featuring one of Adam Dant’s MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND from the forthcoming book of his extraordinary cartography to be published by Spitalfields Life Books & Batsford on June 7th.

Please support this ambitious venture by pre-ordering a copy, which will be signed by Adam Dant with an individual drawing on the flyleaf and sent to you on publication. CLICK TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY OF MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND BY ADAM DANT

Click to enlarge and study the details of Industrious Shoreditch

A century before the New Industries that define Shoreditch today, there were once the Old Industries. Then, small manufacturers and their suppliers occupied every building, and the neighbourhood teemed with skilled workers and craftsmen who made things with their hands. Cartographer extraordinaire Adam Dant celebrates this culture with his Map of Industrious Shoreditch, 1912.

“I chose 1912 because it precedes the First World War, when everything changed. It encapsulates Industrious Shoreditch,” explained Adam, “I started off with the major landmarks serving the industries of the time. For the main thoroughfares, I listed the concentrations of manufacturers, using lists of companies from the Post Office Directories. These are complemented by vignettes of people making things, and I filled the border with machines used for wood and metalwork.”

After the First World War, many of the industries moved to larger factories outside London and the twentieth century saw the decline of manufacturing in Shoreditch, with the hardware shops and suppliers of raw materials being the last to go, holding on even into recent decades. Now that Shoreditch is booming again with new technology companies occupying many of the old buildings once used for manufacturing, Adam Dant’s map offers us a poignant opportunity to explore that lost world of industriousness.

You will discover mattress makers, french polishers, feather dyers, hatters, bootmakers, chandlers, over-mantle manufacturers, cabinet makers, coach builders, wood turners, corset makers, and more…

Adam Dant goes in search of Industrious Shoreditch

CLICK TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY OF MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND BY ADAM DANT

Adam Dant’s MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND is a mighty monograph collecting together all your favourite works by Spitalfields Life‘s cartographer extraordinaire in a beautiful big hardback book.

Including a map of London riots, the locations of early coffee houses and a colourful depiction of slang through the centuries, Adam Dant’s vision of city life and our prevailing obsessions with money, power and the pursuit of pleasure may genuinely be described as ‘Hogarthian.’

Unparalleled in his draughtsmanship and inventiveness, Adam Dant explores the byways of English cultural history in his ingenious drawings, annotated with erudite commentary and offering hours of fascination for the curious.

The book includes an extensive interview with Adam Dant by The Gentle Author.

Adam Dant’s limited edition prints are available to purchase through TAG Fine Arts

Readers are invited to visit the London Original Print Fair at the Royal Academy this weekend where some of Adam Dant’s prints are being displayed. Click here for two complimentary tickets.

The Little Yellow Watch Shop

John Lloyd, Watch Repairer

When you step into The Little Yellow Watch Shop in the Clerkenwell Rd, you discover yourself among an eager line of customers clutching their precious timepieces patiently and awaiting the moment they can hand them into the safe hands of John Lloyd, the watch repairer who has worked in Clerkenwell longer than any other. With his long snowy white locks, John looks like a magus, as if by merely peering down critically over his long nose at a broken watch and snapping his fingers, he could conjure it back into life.

While John works his charm, his wife Annie Lloyd fulfils the role of magician’s assistant with consummate grace, taking down all the necessary information from the owner and keeping everything moving with superlative efficiency. Together they preside over a hundred watches a week arriving for repair, and thereby maintain the tradition of clock-making and repair that has occupied Clerkenwell for centuries.

John has worked in the Clerkenwell Rd since 1956 and remembers when every shop between St John St and Goswell Rd was a watch repair or watch materials supply shop. Today, although his business is now one of just a tiny handful remaining in Clerkenwell, it is apparent that there is a healthy demand for his services to sustain him for as long as he pleases.

“I’m from Shepherd’s Bush originally and my stepfather had a watch repair stall in Romford Market,” John admitted to me, “I was only eleven when I started to work with him, but I quickly took to it.”

“I first came to Clerkenwell in the nineteen-forties, when I did a three year course in Instrument Making at the Northampton Polytechnic, now known as the City University. Then I joined A. Shoot & Sons in Whitechapel at seventeen years old, was conscripted for National Service at eighteen and returned to my job again in 1956. Shoot & Sons supplied watch materials from a tall thin building at 85 Whitechapel High St next to the Whitechapel Gallery, but in that year we moved to Whitworth Buildings in Clerkenwell and then to the corner of St John St & Clerkenwell Rd in 1959. At Shoot & Sons, I used to go to the manager Leslie Lawson at weekends and we stripped down antique watches together – not many people these days know the inside workings of a watch.”

In 1992, when Shoot & Sons Ltd closed after more than thirty years on the corner, John moved to the kiosk fifty yards away at 60 Clerkwenwell Rd which was even smaller than the current Little Watch Shop. He opened it in partnership with his colleague Barry Benjamin but, when Barry became ill after just three years, John continued the business alone until his wife Annie came in one day a week and then later joined him full time. What was once a miniscule kiosk has expanded into a tiny shop where John presides happily from behind the counter, surrounded by photos of old Clerkenwell and his step-father’s sign from Romford market where John started out in the nineteen-forties.

“People ask me when I ‘m going to retire,” John confided to me gleefully, “but I’m already past retirement age – I’m having too much fun here.”

John Lloyd – Clerkenwell’s longest-serving member of the watch business

John’s mother and stepfather in Brighton, 1954

At Shoot & Sons Ltd

Maurice Shoot, John’s boss from the early fifties until his retirement in 1989

Phil, John and Barry at Shoots

Shoot & Sons Ltd on the corner of St John St & Clerkenwell Rd in the eighties

The interior of the shop at Shoot & Sons Ltd

60 Clerkenwell Rd in 1900, note the watch and clock shops

Clerkenwell Rd in the sixties

Barry Benjamin outside the original Little Yellow Shop

Signs uncovered in the expansion of the Little Yellow Shop

John & Annie Lloyd

Portraits © Estate of Colin O’Brien

The Little Yellow Shop, watch service centre, 60 Clerkenwell Rd, EC1

You may like to read these other Clerkenwell stories

At Embassy Electrical Supplies