Working Lads Of Whitechapel

These portraits were taken around 1900 at the Working Lads Institute, known today as the Whitechapel Mission. Founded in 1876, the Institute offered a home to young men who had been involved in petty criminal activity, rehabilitating them through working at the Mission which tended to the poor and needy in Whitechapel. Once a lad had proved himself, he was able to seek independent employment with the support and recommendation of the Institute.

The Working Lads Institute was the first of its kind in London to admit black people and Rev Thomas Jackson, the founder, is pictured here with five soldiers at the time of World War I

Stained glass window with a figure embodying ‘Industry’ as an inspiration to the lads

In the dormitory

Rev Thomas Jackson & the lads collect for the Red Cross outside the Mission

Click here to learn more about The Whitechapel Mission

You may also like to take a look at

‘No Enemy But Winter & Rough Weather…’

‘No enemy but winter and rough weather…’

Every year at this low ebb of the seasons, I go to Columbia Rd Market to buy potted bulbs and winter-flowering plants which I replant into my collection of old pots from the market and arrange upon the oak dresser, to observe their growth at close quarters and thereby gain solace and inspiration until my garden shows convincing signs of new life.

Each morning, I drag myself from bed – coughing and wheezing from winter chills – and stumble to the dresser in my pyjamas like one in a holy order paying due reverence to an altar. When the grey gloom of morning feels unremitting, the musky scent of hyacinth or the delicate fragrance of the cyclamen is a tonic to my system, tangible evidence that the season of green leaves and abundant flowers will return. When plant life is scarce, my flowers in pots that I bought for just a few pounds each at Columbia Rd acquire a magical allure for me, an enchanted quality confirmed by the speed of their growth in the warmth of the house, and I delight to have this collection of diverse varieties in dishes to wonder at, as if each one were a unique specimen from an exotic land.

And once they have flowered, I place these plants in a cold corner of the house until I can replant them in the garden. As a consequence, my clumps of Hellebores and Snowdrops are expanding every year and thus I get to enjoy my plants at least twice over – at first on the dresser and in subsequent years growing in my garden.

Staffordshire figure of Orlando from As You Like It

Kevin O’Brien, Retired Road Sweeper

Kevin O’Brien at Tyers Gate in Bermondsey St with Gardners’ Chocolate Factory behind

On a bright cold morning recently, I walked down to Bermondsey St to meet Kevin O’Brien and enjoy a tour of the vicinity in his illuminating company, since he has passed most of his life in the close proximity of this former industrial neighbourhood. Nobody knows these streets better than Kevin, who first roamed them while playing truant from school and later worked here as a road sweeper. Recent decades have seen the old factories and warehouses cleaned up and converted into fashionable lofts and offices, yet Kevin is a custodian of tales of an earlier, shabbier Bermondsey, flavoured with chocolate and vinegar, and fragranced by the pungent smell of leather tanning.

“I was born and bred in Bermondsey, born in St Giles Hospital, and I’ve always lived in Bermondsey St or by the Surrey Docks. My dad, John O’Brien was a docker and a labourer, while my mum, Betsy was a stay-at-home housewife. He didn’t believe in mothers going to work. He was a staunch Irishman, a Catholic but my mum she was a Protestant. I’ve got six brothers and two sisters, half of us were christened and half ain’t.

I grew up in Tyers Gate, a three bedroom flat in a council estate for nine children and mum and dad, eleven people. It was quite hard, we topped and tailed in the bedrooms. From there, we went into a house with three bedrooms in Lindsey St off Southwark Park Rd. It had no bath or inside toilet, so it was quite hard work living there for my mum. Bermondsey was always an interesting place because I had my brothers and my sisters all around me, and I had lots of good friends. Our neighbours were good. We helped one another out and everybody mucked in. Those were hard times when I was a kid after the war.

We used to play in the bombed-out church in Horselydown. That was our playing field and we crawled around inside the ruins. There were feral cats and it was filthy. We’d come home filthy and my mother would give us a good hiding. My brother, Michael loved animals and he used to bring cats home with him but my mother would take them back again. He was terrible, he wanted every animal, he would fetch home pigeons – the whole lot.

We were playing once and I fell in the ‘sheep dip’ – one of the vats used for tanning leather. We were exploring and we climbed down these stairs but I fell through a missing stair and into this ‘dip.’ It sucks you under. It stinks. It’s absolutely filthy. It’s slime. They had to drag me out by my arms. I went home and my mum made me take all my clothes off outside the front door on the balcony before scrubbing me down with carbolic soap and a scrubbing brush. All of me was red raw and I never went back in there again. It taught me a lesson. My mum was hard but fair.

In those days, the industries in Bermondsey were leather, plastic, woodwork and there was a chocolate factory. Nearly everybody in Bermondsey St worked in Gardners’ Chocolate Factory at some point. My first job was there, I worked the button machine, turning out hundred and thousands of chocolate buttons every day.

I hated school. I never liked it. I really hated it. I used to run out of school and they had trouble getting me back. I roamed the streets. The School Board man was always round our house, not just for me but for my brothers as well – although they went to school and actually managed to learn to read and write. Me, I hated it because I didn’t want to learn. I left when I was fifteen and went to work in the chocolate factory, I started as a labourer and worked my way up to being a machine operator. It was better than the apprenticeship I was offered as a painter and decorator at three pounds a week. At Gardners’ Chocolate Factory I was offered nine pounds and ten shillings a week. I was still living at home and my brothers couldn’t understand how I could put half of my earnings in a savings book. They couldn’t save but I didn’t drink. I didn’t like the taste of it. I didn’t start drinking until I was twenty-one or twenty-two. I was a late starter but I’m making up for it now.

I was always in the West End. I loved Soho and I liked being in the West End because I was free and I could do what I wanted. As a gay man in Bermondsey, it was hard. So all my friends and the people I got to know were in the West End. There were loads of gay places, little dive bars in Wardour St, as small as living rooms. The Catacombs was one I went to, in Earls Court. That was a brilliant place. When I was thirteen, I got into The Boltons pub. It was hard work, getting into pubs but you got to know other people who were gay. You could get arrested for being gay and that was part of the excitement. There was fear but you got to meet people.

I was about fifteen when I told my mum I was gay. Her first words were, ‘What’s your dad going to say?’ That was hard, because my dad didn’t speak to me for nearly a year. He wouldn’t even sit in the same room as me. He was such hard work. If I was going out anywhere, my brothers and sisters would say ‘He’s going out to meet his boyfriends!’ But they all loved me and I loved my family. I could always stick up for myself. If someone said something to me, I’d say something back. I was one of those that didn’t worry what people thought.

I got the sack from the chocolate factory because I didn’t like one of the managers and I threatened to put him in one of the hoppers. I chased him round the machines with a great big palette knife and he sacked me, so I walked straight out of that job, walked round to Sarsons’ Vinegar in Tower Bridge Rd and got another job the same day for more money. It was a two minute walk. Within a matter of two or three weeks, I became a brewer. It was a good job but many people did away with themselves there. They climbed onto the vats of vinegar until they got high on the fumes and fell into it. People were depressed, they had come back from the war to nothing and they couldn’t rebuild their lives.

After the vinegar factory, I got a job with Southwark Council as a road sweeper in Tower Bridge Rd. I couldn’t read or write but I used to memorise all the streets on the list that I had to sweep. Even though I’d walked down many of these streets all my life, I didn’t know their names until I learned to read the signs. It was an interesting job because you got to meet a lot of people on the street and I got chatted up as well. I got to know all the pubs and delivered them bin bags, so I could rely on getting myself a cup of tea and a sandwich. There was always a little fiddle somewhere along the line.

It’s all office work and computers in Bermondsey St now, but I’m here because this is my home. This is where I want to be, all my family are here. There’s loads of locals like me. There’s still plenty of Bermondsey people. I’ve got friends here. We grew up together. It’s where I belong, so I am very lucky. We’ve got a lot here. I walk around, and I go to museums, and I look at buildings. I go to Brighton sometimes just for fish and chips, that’s a very expensive fish and chips!”

“There’s still plenty of Bermondsey people”

Kevin O’Brien at the former Sarsons’ Vinegar Factory in Tower Bridge Rd where he once worked

You may also like to read about

The Toy Theatres Of Old St & Hoxton

William Webb, 49 Old St, 1857

William Webb, 49 Old St, 1857

These days the vicinity of Old St is renowned for its digital industries but, for over a hundred years, this area was celebrated as the centre of toy theatre manufacture in London. For centuries, these narrow streets within walking distance of the City of London were home to highly skilled artisans who could turn their talents to the engraving, printing, jewellery, clock, gun and instrument-making trades which operated here – and it was in this environment that the culture of toy theatres flourished.

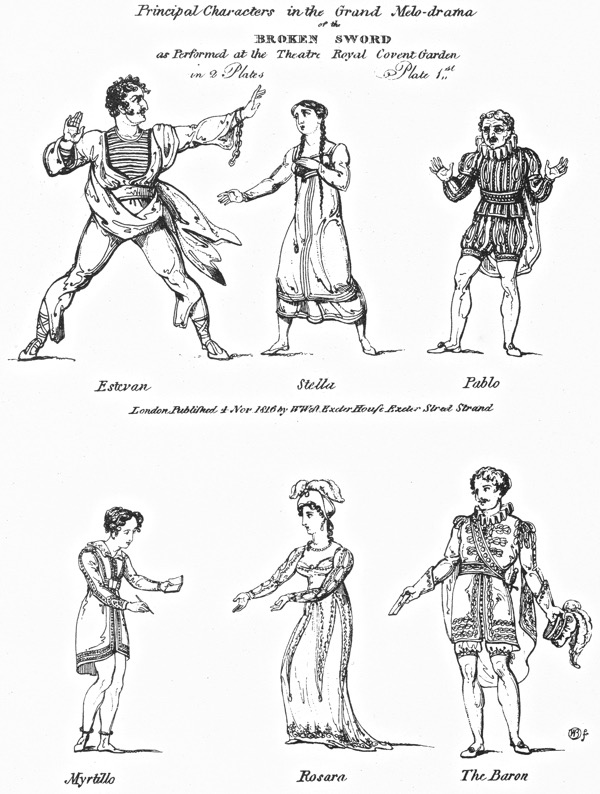

Between 1830 and 1945, at a handful of addresses within a half mile of the junction of Old St and City Rd, the modest art of publishing engraved plates of characters and scenery for Juvenile Dramas achieved its metier. The names of the major protagonists were William Webb and Benjamin Pollock. The overture was the opening of Archibald Park’s shop at 6 Old St Rd in 1830, and the drama was brought to the public eye by Robert Louis Stevenson in his essay A Penny Plain and Twopence Coloured in 1884, before meeting an ignominious end with the bombing of Benjamin Pollock’s shop in Hoxton St in 1945.

Responsibility for the origin of this genre of publishing belongs both to John Kilby Green of Lambeth and William West of Wych St in the Strand, with the earliest surviving sheets dated at 1811. Green was just an apprentice when he had the notion to produce sheets of theatrical characters but it was West who took the idea further, publishing plates of popular contemporary dramas. From the beginning, the engraved plates became currency in their own right and many of Green’s vast output were later acquired by Redington of Hoxton and eventually published there as Pollock’s. West is chiefly remembered for commissioning artists of acknowledged eminence to design plates, including the Cruickshank brothers, Henry Flaxman, Robert Dighton and – most notably – William Blake.

Green had briefly collaborated to open Green & Slee’s Theatrical Print Warehouse at 5 Artillery Lane, Spitalfields, in 1805 to produce ‘The Tiger’s Horde’ but the first major publishers of toy theatres in the East End were Archibald Park and his family, rising to prosperity with premises in Old St and then 47 Leonard St between 1830 until 1870.

Park’s apprentice from 1835-42, William Webb, set up on his own with shops in Cloth Fair and Bermondsey before eventually opening a quarter a mile from his master at 49 (renumbered as 146) Old St in 1857. Webb traded here until his death in 1898 when his son moved to 124 Old St where he was in business until 1931. Contrary to popular belief, it was William Webb who inspired Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous essay upon the subject of toy theatres. Yet a disagreement between the two men led to Stevenson approaching Webb’s rival Benjamin Pollock in Hoxton St, who became the subject of the story instead and whose name became the byword for toy theatres.

In 1876, at twenty-one years old, Benjamin Pollock had the good fortune to acquire by marriage the shop opened by his late father-in-law, John Redington in Hoxton in 1851. Redington had all the theatrical plates engraved JK Green and, in time, Benjamin Pollock altered these plates, erasing the name of ‘Redington’ and replacing it with his own just as Redington had once erased the name ‘Green’ before him. Although it was an unpromising business at the end of the nineteenth century, Pollock harnessed himself to the work, demonstrating flair and aptitude by producing high quality reproductions from the old plates, removing ‘modern’ lettering applied by Redington and commissioning new designs from the naive artist James Tofts.

In 1931, the writer AE Wilson had the forethought to visit Webb’s shop in Old St and Pollock’s in Hoxton St, talking to William Webb’s son Harry and to Benjamin Pollock, the last representatives of the two surviving dynasties in the arcane world of Juvenile Dramas. “In his heyday, his business was very flourishing,” admitted Harry Webb speaking of his father,” Why, I remember we employed four families to do the colouring. There must have been at least fifteen people engaged in the work. I could tell their work apart, no two of them coloured alike. Some of the work was beautifully done.”

Harry recalled visits by Robert Louis Stevenson and Charles Dickens to his father’s premises. “Up to the time of the quarrel, Stevenson was a frequent visitor to the shop, he was very fond of my father’s plays. Indeed it was my father who supplied the shop in Edinburgh from which he bought his prints as a boy,” he told Wilson.

Benjamin Pollock was seventy-five years old when Wilson met him and ‘spoke in strains not unmingled with melancholy.’ “Toy theatres are too slow for the modern boy and girl,” he confessed to Wilson, “even my own grandchildren aren’t interested. One Christmas, I didn’t sell a single stage.” Yet Pollock spoke passionately recalling visits by Ellen Terry and Charlie Chaplin to purchase theatres. “I still get a few elderly customers,” Pollock revealed, “Only the other day, a City gentleman drove up here in a car and bought a selection of plays. He said he had collected them as a boy. Practically all the stock has been here fifty years or so. There’s enough to last out my time, I reckon.”

Shortly after AE Wilson’s visit to Old St & Hoxton, Webb’s shop was demolished while Benjamin Pollock struggled to earn even the rent for his tiny premises until his death in 1937. Harry Webb lived on in Caslon St – named after the famous letter founder who set up there two centuries earlier – opposite the site of his father’s Old St shop until his death in 1962.

Robert Louis Stevenson visited 73 Hoxton St in 1884. “If you love art, folly or the bright eyes of children speed to Pollock’s” he wrote fondly afterwards. Stevenson was an only child who played with toy theatres to amuse himself in the frequent absences from school due to sickness when he was growing up in Edinburgh. I too was an only child enchanted by the magic of toy theatres, especially at Christmas, but I cannot quite put my finger on what still draws me to the romance of them.

Even Stevenson admitted “The purchase and the first half hour at home, that was the summit.” As a child, I think the making of them was the greater part of the pleasure, cutting out the figures and glueing it all together. “I cannot deny the joy that attended the illumination, nor can I quite forget that child, who forgoing pleasure, stoops to tuppence coloured,” Stevenson concluded wryly. I cannot imagine what he would have made of Old St’s ‘Silicon Roundabout’ today.

Drawings for toy theatre characters by William Blake for William West

The sheet as published by William West, November 4th 1816 – note Blake’s iniitals, bottom right

Another sheet engraved after drawings by William Blake, 1814

Another sheet engraved after drawings by William Blake, 1814

124 Old St, 1931

73 Hoxton St (formerly 208 Hoxton Old Town) 1931

Benjamin Pollock at his shop on Hoxton St in 1931

You may also like to read about

At The Whitechapel Mission At Christmas

Today I recall a visit to the Whitechapel Mission with my friend the late photographer Colin O’Brien

Before dawn one Christmas Eve, Photographer Colin O’Brien & I ventured out in a rainstorm to visit our friends down at the Whitechapel Mission – established in 1876, which opens every day of the year to offer breakfasts, showers, clothes and access to mail and telephones, for those who are homeless or in need.

Many of those who go there are too scared to sleep rough but walk or ride public transport all night, arriving in Whitechapel at six in the morning when the Mission opens. We found the atmosphere subdued on Christmas Eve on account of the rain and the season. People were weary and shaken up by the traumatic experience of the night, and overcome with relief to be safe in the warm and dry. Feeling the soothing effect of a hot shower and breakfast, they sat immobile and withdrawn. For those shut out from family and social events which are the focus of festivities for the rest of us, and facing the onset of winter temperatures, this is the toughest time of the year.

Unlike most other hostels and day centres, Whitechapel Mission does not shut during Christmas. Tony Miller, who has run the Mission and lived and brought up his family in this building over the last thirty-five years, had summoned his three grown-up children out of bed at five that morning to cover in the kitchen when the day’s volunteers failed to show. Although his staff take a break over Christmas which means he and his wife Sue and their family have to pick up the slack, it is a moment in the year that Tony relishes. “40% of our successful reconnections happen at Christmas,” he explained enthusiastically, passionate to seize the opportunity to get people off the street, “If I can persuade someone to make the Christmas phone call home …”

Tony estimates there are around three thousand people living rough in London, whom he accounts as follows – approximately 15% Eastern Europeans, 15% Africans and 5% from the rest of the world, another 15% are ex-army while 30%, the largest proportion, are people who grew up in care and have never been able to establish a secure life for themselves.

Among those I spoke with on Christmas Eve were those who had homes but were dispossessed in other ways. There were several vulnerable people who lived alone and had no family, and were grateful for a place where they could come for breakfast and speak with others. Here in the Mission, I recognised a collective sense of refuge from the challenges of existence and the rigours of the weather outside, and it engendered a tacit human solidarity. “This is going to be the best Christmas of my life,” Andrew, an energetic skinny guy who I met for the first time that morning, assured me, “because it’s my first one free of drugs.” We shook hands and agreed this was something to celebrate.

Tony took Colin & me upstairs to show us the pile of non-perishable food donations that the Mission had received and explained that on Christmas Day each visitor would be given a gift of a pair of socks, a woollen hat, a scarf and pair of gloves, with a bar of chocolate wrapped inside. Tony told me that on Christmas Day he and his family always have a meal together, but his wife Sue also invites a dozen waifs and strays – so I asked him how he felt about the lack of privacy. “My kids were born here,” he replied with a shrug and a smile and an astonishing generosity of spirit, “after thirty years, I don’t have a problem with it.”

Food donations

Photographs copyright © Estate of Colin O’Brien

Click here to donate to the work of the Whitechapel Mission

You may also like to read about

The Disappearing Pubs Of Marylebone

In the spring of 2014, I enjoyed a memorable afternoon undertaking a crawl around historic pubs in Marylebone but since then I have been receiving reports of an alarming number of closures in this attractive backwater. So yesterday I set out on a melancholy pilgrimage at the year’s end to say farewell to the disappearing pubs of Marylebone – needless to say I returned footsore and thirsty.

The Beehive in Homer St, opened before 1848 (photographed in 2014)

The Beehive is now being redeveloped

Two regulars at The Harcourt Arms, in Harcourt St since 1869 (photographed in 2014)

The Harcourt Arms is no longer a pub but now The Harcourt, a restaurant

The Windsor Castle in Crawford Place since 1856 closed in August for redevelopment into luxury flats

It is rumoured The Lord Wargrave built in 1866 in Crawford Place may be closing soon

The Victory in Brendon St since 1829 became a restaurant this year

The Duke of York in Harrowby St since 1827 shut last summer but an application for a new licence has been submitted

The Duke of Wellington built in 1812 in Crawford St recently closed

The Beehive in Crawford St was first licenced in 1793, was rebuilt in 1884 and is currently derelict after a recent fire

The Beehive, Crawford St

The Tudor Rose in Blandford St opened in 1841 as ‘Le Fevre’s Coffee House,’ becoming ‘The Lincoln Hotel’ by 1852, then rebuilt as ‘The William Wallace’ in 1936 and renamed ‘The Tudor Rose’ in 2000 but shut this year with a recent planning application to alter the exterior

Interior of The Tudor Rose in 2014

Interior of The Tudor Rose today

Stained glass at The Tudor Rose

The Dover Castle, Weymouth Mews since 1807 shut for redevelopment in September (photographed in 2014)

The Dover Castle in 2014

The Dover Castle today

The Pontefract Castle opened in 1869 in Wigmore St but is now only the facade of a new development

The George in Great Portland St opened before 1839 but has now shut

Approximately ten pubs are closing for good in London each week at present

You may also like to take a look at

Doris Halsall, Civil Servant & Despatch Rider

Doris Halsall, Despatch Rider, 1944

One Saturday afternoon recently, I took the train over to Chigwell to visit Doris Halsall – still vital and independent in her ninety-sixth year – who recounted for me the story of her circuitous journey through the twentieth century and away from the East End. Blessed with keen intelligence and an adventurous nature, Doris embraced the possibilities for advancement that came her way – especially riding a motor bicycle – with enthusiasm and fearless determination, boldly constructing a life for herself that transcended her modest beginnings.

“I was born in 3 Venner Rd in Bow in 1920. My mother, Rosina & father, Alfred White lived in the downstairs with my sister, Rose and I. But later, when my mother’s sister died leaving a little boy of ten days old, Jack, my father said ‘Let us adopt him,’ even though my mother had eight or nine sisters.

Mrs Blewdon, who owned the house, lived upstairs and she came down every morning with her bucket and jug to empty them in the outside toilet and fill them again in the scullery. She stayed the whole day in her room and, each evening, she left us a note on the stairs, ‘I’m in for the night, Mrs White, Good Night.’ I always laughed because I used to love that little note on the stairs.

My father was in the army in the 1914-18 War and I’ve got a certificate to say that in 1916 he was unfit for service. There was no reason given but my mother always insisted that he was gassed and he was ill because of it, although his death certificate said ‘tuberculosis.’ When he came out of the army he did all sorts of jobs. I remember one day he was hoping it would snow, so he could go and do some snow shovelling. Eventually he joined the GPO and he would always bring newspapers to show me the events of the day. He died when I was ten years old in 1930. We were all there at the very last when he was dying. We didn’t think it was terrible, we just accepted it. In the family, there were others that died of tuberculosis.

My mother worked at home and we all helped her. I could cover you an umbrella now! She used to go up to the City and came back with the cloth and the umbrella frames, and we would fit the covers, the three of us – my mother, my sister & I – preventing, tying-in and tipping. Then next day, my mother would take the bundle back on the tram. It was hard for her schlepping up to the City everyday. I still have one of her tram tickets which I use as a bookmark. Later on, she used to knit angora berets and I sewed them up. She was always afraid we’d go into the workhouse, Bromley by Bow Workhouse was nearby.

After my father died, we were no more or less poor than we were when he was alive. My mother had a ten shillings a week pension, five shillings for my sister and three shillings for me – nothing for my cousin. We never saw ourselves as poor. We just accepted life. I was quite a happy child but my sister wasn’t, she was always unhappy and I don’t know why – I think it’s the way you are born. So I was never unhappy, but our circumstances were dreadfully poor. The coalman came round to our road but we couldn’t afford to have a sack of coal, it was half a crown for a hundredweight.

In Burdett Rd nearby, there was a little row of shops including a sweet shop with these different kinds of sweets in sections. All I ever wanted was to buy a quarter of pear drops for tuppence and I thought, ‘When I grow up, I’ll buy them.’ There were fruit stalls with oranges that came in fine crates made of wood which the stallholders would just throw down and the council would come and collect them, but we could go along and pick up the wood and take it home and put it on the fire. So why did you need to buy a hundredweight of coal for half a crown?

My sister & I played all the time in the street with my brother-come-cousin sat in the pushchair outside the house. We had all our friends on the street, our neighbour Mrs Franklin had nine children, and there was always entertainment on the street. The barrel organ would come along with these men dressed as women. We didn’t know anything abut transvestites, but they sang and danced and someone turned the barrel organ. The milk cart came along with a big churn and we would take a jug out. We’d buy jam at the little corner shop. We took a cup along and they’d weigh the cup and then they’d fill it with two penny worth of jam from a big jar.

When I was about twelve, I remember walking up to a shop in the City next to the Aldgate Pump to buy a postcard of Leonardo Da Vinci that I had learnt about from a very good art teacher at my school. The question was, ‘How to get tuppence?’ so there was no question of taking the tram or bus, I walked there. I can’t remember if I ever went to the West End but my mother used to take us to Southend for the day by train. I remember looking over the bridge from Bromley by Bow station at the workhouse. All the women used to sit along the wall in their blue and white dresses and, on the other side, sat all the men in their blue and white shirts, separated.

I remember Mosley’s blackshirts when they came down as far as Canal Bridge and I remember going down to see them. I was sixteen and I didn’t think too much about it. They were marching and they’d strayed over as far as Canal Rd. They’d been pushed back and after the Battle of Cable St and they were milling about trying to find a way home.

Opposite Stepney Green station, there was a Methodist Mission and there was this couple, Mr & Mrs Mackie and they took a group of girls under their wing. They took us on holiday for a week and we paid them ten shillings. They were very good to us. They ran a competition for ‘Recitation’ but I called it ‘Elocution.’ I went to a school where they always impressed on us that, if you come from the East End, it doesn’t mean you have to speak like someone from the East End. My cousins made fun of me because I spoke differently, mimicking me, but I didn’t care. I won the District and then the All-London Competition and I got invited stay to tea. That was a real treat. I still have my medal. My recitation began ‘No strong drink for this champion..’ and I had to sign the Temperance pledge. Conveniently, my memory is clouded about when I broke that.

I went to a very good school and I won a Junior County Scholarship with a grant of twelve pounds a year and, when I was fourteen, another grant of twenty-one pounds a year. It was very sad really. Most of the parents wanted their children to leave school and go to work. You were brought up to go and work when you were fourteen. My sister had left at fourteen and was already working and my mother wanted me to leave, but when I did she had to give me money for fares to London and for lunches so she wasn’t much better off.

I wanted to go into the Civil Service which most of my friends were doing but you couldn’t take the exam until you were eighteen. I worked in an office and went to night school, after I left school at sixteen, and finished my education that way. This lady in the office, who seemed ever so much older than me, said ‘Don’t stay here.’ Fortunately, I passed the Civil Service exam and went to work at the Ministry of Agriculture office in Leonard St in Shoreditch and it was all very nice until the War came along.

I was evacuated up to Lytham St Anne’s. We were put into seaside boarding houses and every morning we could smell our rations going past our doors! It was all girls, eight or nine of us, and Mrs Brooks did us well. We had a great time. We borrowed each other’s clothes and went out to the Tower Ballrooms. It was lovely. I was promoted in the Ministry of Agriculture and sent to Bournemouth. We were importing agricultural machinery from America and my job was to look after the shipments as they came in.

My mother stayed in the East End of London all through the war, even though she had a bomb drop next door and had to move out for a while, but she went to work in munitions and became quite well off. She had the Anderson shelter in the garden and she wasn’t a worrier. Yet all the bomb debris in the East End was horrible and cousin of mine was killed in her house with her two little children.

During the war, I wanted to go into the forces but I was considered too useful so I wasn’t allowed to be released from my job. I tried to get into the airforce, in the Meteorological section. I was attracted to the challenge but I wasn’t allowed to do this. Then an offer came along to be a Despatch Rider for the Home Office. My friend Claire & I signed up for that right away, and we went to Hendon Police for week and learnt to ride a motorbike. It was great.

At that time, we were quite sure there was going to be an invasion. In preparation for this, we had to drive around to Police Stations and hand in ‘despatches’ but we never knew what they were – probably a blank sheet. It was just practice and quite soon we knew exactly how to get to the various police stations.

Claire & I often got caught up in the American convoys with all the GIs sitting out on the tailboards while we were on our bikes. They would shout ‘Gee, they’re dames!’ and they wouldn’t let us overtake them – so we had a high time, until they turned left. I had various boyfriends. All the girls in the office had boyfriends or fiances and ever so many of them were killed. I had some boyfriends that weren’t English who went off and I never knew what happened to them.

When the invasion was expected, I was brought back from Bournemouth to London and I went back to live with my mother and she made a great fuss of me. My mother had married again, to Jim Mason, a crane driver in Ilford and they had moved out to Seven Kings. He was a nice man and I liked him ever so much. My mother was glad to leave the East End.

I was married in 1947. I met my husband, Harold Halsall at holiday camp on the East Coast. I had a travelling job then for the Ministry of Agriculture and I visited regional offices examining the accounts. Leaving London by train, I remember once I realised I had left some papers at the office, so I left my case on the platform and went back to the office and, when I returned, it was still there.

After we married we bought a house and lived in Ilford and had two little girls, Pauline & Julia. Rationing continued after the war but there were ways and means of getting hold of what you needed. When I was travelling I visited all the farming towns, so I had eggs and bacon and cheese and milk – and I stayed in hotels, there was no rationing in hotels. It was lovely. I was very fortunate. I have had such a great time. I don’t miss the East End because I wanted to have something better. It was hard, a tough existence and this was a much nicer life.”

Doris in the forties

Doris & her friend Claire, Despatch Riders in 1944

Doris’ mother Rosina and father Alfred, and his sister Emily, photographed at Southend in 1919

Doris with her mother, Rosina, in the twenties

Doris’ family in 1940 – Doris, her sister Rose and their mother Rosina in front.

Doris at the Ministry of Agriculture, Baker St Office, 21st May 1940

Youth Hostelling – Doris’ sister Rose, Doris, Doris’ friend Claire

Acrobatics by ‘Daredevil Doris,’ Corton, 1948

Doris in her new beach-robe, Howstrakes, June 1947

Doris with Harold Halsall on Oulton Broad, July 1947 – the year of their marriage

The first house which Doris and Harold bought on Kirkland Avenue in Ilford – note Doris’ motorbike

Doris, 1949

Doris Halsall, Chigwell 2016

You may also like to read about