At The Blind Beggar In Whitechapel

David Dobson, Landlord of the Blind Beggar

Henry VIII at the gaming machine – a rare image of this infamous monarch not recorded by Holbein yet a familiar sight in Whitechapel, where David Dobson landlord of The Blind Beggar delights to dress up in velvet robes and swan around like the ghost of the old king come back to haunt us.

The particular blind beggar in question is Henry de Montfort who lost his sight at the Battle of Evesham in 1265 and became the subject of a Tudor ballad recounting the myth of his salvation by a young woman of Bethnal Green – where he ended his years begging at the crossroads, cared for by his only daughter. Subsequently, the image of the beggar and his daughter became the seal of the Metropolitan Borough of Bethnal Green in 1900 and adorns the inn sign of The Blind Beggar in Whitechapel today.

Paradoxically, The Blind Beggar has become a site of pilgrimage for the devout, seeking the location of the founding of the Salvation Army by William Booth, who started his independent mission by preaching outside in 1865. Converted to housing now, the former Albion Brewery stands next door towering over the pub that served as its tap room, until it closed in 1979. In 1808, it was the enterprising landlord of The Blind Beggar who bought the small brewery next door and named it the Albion Brewery, which grew to be the third largest in Britain by 1880 and, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the first Brown Ale was brewed here by Thomas Wells Thorpe.

In 1904, ‘Bulldog’ Wallace, a member of The Blind Beggar Gang of pickpockets who frequented the pub, stabbed another man in the eye with an umbrella – initiating the notoriety that coloured the reputation of the pub in the twentieth century, which reached its nadir with the shooting of Georgie Cornell by Ronnie Kray in March 1966, as recounted to me by Billy Frost, the Kray Twins’ driver.

“We don’t glorify it, we want to be famous for other things,” admitted David Dobson when I joined him for a jar. “For example, I’ve got the finest collection of Japanese Carp in the East End,” he volunteered, as he led me into the garden and leaned over the vast tank full of fish, each as fat as my leg, so that his beloved charges might lift their heads from the water and permit him to stroke them affectionately under the chin.

“I enjoy the diversity of my clientele,” David confided, when I enquired about the rewards of his job, “Every day, I meet people from all over the world. We’ve had Jerry Springer here, and Brad Pitt’s popped in.”

Yet in spite of the glamour and the attention, David’s motive for acquiring the Blind Beggar is refreshingly simple. “I like drinking, so I bought the pub,” he confessed to me with an eager grin, raising a glass as he revealed a lifelong commitment to his pub, “It’s not a job for me, it’s way of life. I’m live here and I’m in every night – I’ll be leaving here in a box.”

The Blind Beggar, mid-nineteenth century – there has been a pub on this site since 1673

The current building was constructed in 1894

The Albion Brewery

The Watney Mann Brewery with The Blind Beggar attached

The Blind Beggar and the former Albion Brewery today

David Dobson, Publican & Proprietor

David and his Koi Carp

David pets his not-so-coy carp

“I wore it for a fancy dress party years ago, but now it’s just a habit.”

David and a local wag

David waits to welcome the Olympic Torch to Whitechapel in 2008

David Dobson – “I like drinking, so I bought the pub”

Colour photographs copyright © Estate of Colin O’Brien

The Blind Beggar, 337 Whitechapel Rd, London E1

You may also like to read about

The Disappearing Pubs of Marylebone

Sandra Esqulant, The Golden Heart

Phil Maxwell Returns To Sclater St Market

Markets are commonly assumed to be ephemeral, transitory phenomena compared to the buildings which surround them, yet very often the opposite is true. The Sclater St Market has persisted tenaciously through at least two centuries of architectural change. In spite of new blocks of flats in the generic modern London style looming overhead, Contributing Photographer Phil Maxwell found it as lively as ever with some of the same characters present from the eighties when he first began photographing markets in Spitalfields. ‘This market community is the last bastion of East Enders in the face of redevelopment,’ he informed me with pride and delight.

Photographs copyright © Phil Maxwell

You may also like to take a look at

Richard Lee of Sclater St Market

Robert Green of Sclater St Market

Phil Maxwell in Bethnal Green Rd

Phil Maxwell in Bethnal Green Rd

Phil Maxwell’s Kids On The Street

Phil Maxwell’s East End Cyclists

Phil Maxwell & Sandra Esqulant

The Nippers At The William Morris Gallery

On Thursday 19th January, I shall be giving an illustrated lecture about Horace Warner’s SPITALFIELDS NIPPERS and telling the stories behind his breathtaking photographs at the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow. It is a singularly appropriate venue because Horace Warner was connected to William Morris through the Warner family wallpaper business of Jeffrey & Co who printed the wallpaper for Morris & Co. Click here for booking information

[youtube WOJlJ0qfFrs nolink]

Click here to order a copy of SPITALFIELDS NIPPERS by Horace Warner

You may also like to read about

Andrew Baker At Hiller Bros

Photographer Andrew Baker went along to capture the last days of Hiller Bros Market Barrow Makers in Bethnal Green after reading about the closure of the workshop last November on Spitalfields Life and here are a selection of his pictures

“As a kid I would see Market barrows all the time, wooden-wheeled with steel tyres, usually painted with lead paint in green and red, when I was out with me mother and grandmother (or Nan as I called her) during our regular visits to the High Street, Walthamstow Market or during occasional trips to Romford and the much heralded ‘The Roman’ – Roman Road Market. Now I only see three original barrows: one at Chrisp Street Market, pictured below, another on Bethnal Green Road, and one at Queens Market.

So when Hiller Brothers’ workshop was being cleared out I went to take a look. They were moving to new premises, after seventy-odd years. A familiar smell of damp wood and oxidised steel added to the cold November morning. There were a couple of blokes inside. Joe was the first I spoke to, after he finished talking to a woman, who seemed to be the guvnor. It was left to me to decide, after the other nodded and gestured ‘It’s him you need to speak to,’ when I asked to take a few photographs. ‘Quick’ the women said to me, ‘it,s all going, going forever!’ with a hint of excitement, pleased with a trophy she had just acquired .

What I found most surprising was the industry behind these barrows. To this day. the barrows are rented out and maintained by Hillers, with their leaf spring suspension, wooden wheels with steel tyres, made by a wheelwright – another artisan trade of the past – and crafted handles. These are heavy carts and cannot be maintained by just anyone.

The skill and craftsmanship that Hillers maintain to this day is remarkable. The name ‘Hiller Bros’ is always carved, free hand, by one of the Hillers, ‘Wouldn’t even be marked out with a pencil’ Mick told me.

I asked Mick how long he had worked with Market barrows and he replied, ‘Well I don’t know, but my daughter was conceived on one and she’s forty-seven!'”

– Andrew Baker

Hiller Bros barrow in use in Chrisp St Market

Photographs copyright © Andrew Baker

You may also like to might to read my original story

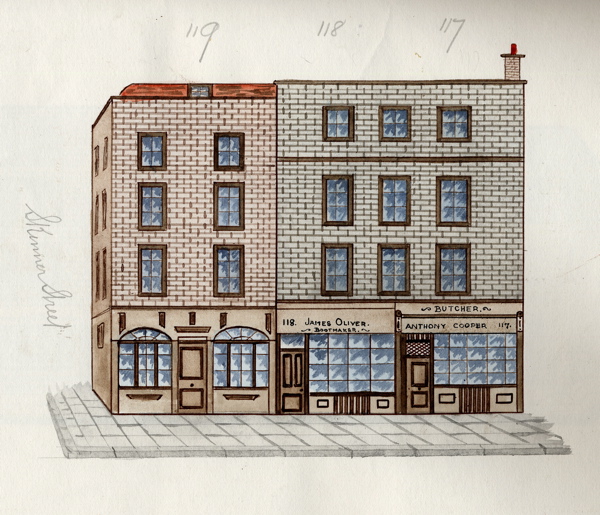

Tallis’ Street Views Of Bishopsgate 1838

Site of Bishopsgate Institute

The same location today

Before anyone ever dreamed of Google Street Views, there were Tallis’s London Street Views of the eighteen-thirties “to assist strangers visiting the Metropolis through all its mazes without a guide.” John Tallis created the precedent of a map which included pictures of all the buildings as a visual aid, commissioning the unfortunately-named artist Charles Bigot to do the drawings and writer William Gaspey to create the accompanying text. Tallis had his imitators, evidenced by this beautiful set of anonymous watercolours of every single facade in Bishopsgate, Spitalfields, dated to 1838 and preserved at the Bishopsgate Institute.

There is an obsessive quality to these paintings which drew my attention when I first came upon them, displaying an amateurism in the brushwork and lettering that recalls folk or outsider art. I cannot deny the appeal of recording every facet of the world in this way because there is a strange reassurance to be gained from looking at these neat little pictures. They are reminiscent of the visualisations created for buildings that are yet to be built, in which less salubrious elements are excluded in images designed to endear us to the proposals of architects and developers.

Although these views of Bishopsgate advertise their veracity by recording every single brick, I do not believe it actually looked like this because the buildings are uniformly clean and well maintained. In contrast to the chaotic nature of Google Street Views that record our contemporary cityscapes, there is a comic flatness in these drawings. They are more reminiscent of street scenes in toy theatres and those houses you find on model railway layouts, tempting me to paste them onto matchboxes and create my own personal Bishopsgate. Neat, tidy and eminently respectable, the early nineteenth century society envisioned by these innocuous facades is that of Adam Smith’s “nation of shopkeepers.”

While Bishopsgate itself is unrecognisably altered from the time of these drawings, the proportion of the buildings, providing a shop on the ground floor, with family accommodation and sometimes workshops above, is still familiar in Spitalfields today. The two stocks of brick used, red brick and the London yellow brick remain the predominant colours over one hundred and fifty years later. Sir Paul Pindar’s House, illustrated in the penultimate plate, was the lone survivor from the time before the Fire of London when Spitalfields was a suburb where aristocrats had their country residences. Today the frontage of Sir Paul Pindar’s House can be viewed at the Victoria & Albert Museum where it was moved in 1890.

Named Ermine St by the Romans, for centuries Bishopsgate was the major approach to the City of London from the north leading straight down to London Bridge, and the saddler and harness makers, and coach builders who set up business in the street reflected the nature of this location as a point of arrival and departure. There are some age-old trades recorded in these pictures which survived in Spitalfields until recent times, upholsterers, umbrella makers and leatherworkers, while the straw hat makers, cutlers, dyers, tallow sellers and corn dealers went long ago. Yet we still have plenty of hair dressers today. Let me admit, my favourite business here is Mr Waterworth, the Plumber – who could become a credible addition to a set of Happy Families, along with all his little squirts.

Corner of Houndsditch

Corner of Houndsditch

Corner of Union St, now Brushfield St

Corner of Brushfield St today

Corner of Primrose St

Corner of Primrose St

This space is now occupied by Liverpool St Station and the frontage of Sir Paul Pindar’s House is in the Victoria & Albert Museum

Archive images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

The Romance of Old Bishopsgate

Margaret Rope’s Haggerston Windows

A familiar East End scene of 1933 – children playing cricket in the street and Nipper the dog joining in – yet it is transformed by the lyrical vision of the forgotten stained glass artist Margaret Rope, who created a whole sequence of these sublime works – now dispersed – depicting both saints of legend and residents of Haggerston with an equal religious intensity.

This panel is surmounted by a portrayal of St Leonard, the sixth century French saint, outside a recognisable St Leonard’s church, Shoreditch, with a red number six London bus going past. Margaret Rope’s extraordinary work mixes the temporal and the spiritual, rendering scenes from religious iconography as literal action and transforming everyday life into revelations – describing a universe simultaneously magical and human.

Between 1931 and 1947, the artist known simply to her family as ‘”Tor,” designed a series of eight windows depicting “East End Everyday Saints” for St Augustine’s church off the Hackney Rd, portraying miracles enacted within a recognisable East End environment. For many years these were a popular attraction, until St Augustine’s was closed and Margaret Rope’s windows removed in the nineteen-eighties, with two transferred across the road to St Saviour’s Priory in the Queensbridge Rd and the remaining six taken out of the East End to be installed in the crypt of St Mary Magdalene, Munster Sq. Intrigued by the attractive idea of Margaret Rope’s transcendent vision of the East End, I set out to find them for myself.

At St Saviour’s Priory, Sister Elizabeth was eager to show me their cherished windows of St Paul and St Margaret, both glowing with lustrous colour and crammed with intricate detail. St Paul, the patron saint of London, is depicted at the moment of his transformative vision, beneath St Paul’s Cathedral – as if it were happening not on the road to Damascus but in Ludgate Circus. The other window, portraying St Margaret, has particular meaning for the sisters at St Saviours, because they are members of the Society of St Margaret, whose predecessors first came from Sussex to Spitalfields in 1866 to tend to the victims of cholera. In Margaret Rope’s window, St Margaret resolutely faces out a dragon while Christ hands a tiny version of the red brick priory to John Mason Neale, the priest who founded the order. Both windows are engaging exercises in magical thinking and the warmth of the colours, especially turquoise greens and soft pinks, delights the eye with its glimmering life.

I found the other six windows in the crypt of St Mary Magdalene near Regents Park, now used as a seniors’ day centre, where they are illuminated from the reverse by fluorescent tubes. The first window you see as you walk in the door is St Anne, which contains an intimate scene of a mother and her two children, complete with a teddy bear lying on the floor and a tortoiseshell cat sleeping by the range.

Next comes St George, who looks like a young athlete straight out of the Repton Boxing Club, followed by St Leonard, St Michael, then St Augustine and St Joseph. All share the same affectionate quality in their observation of human detail that sets them above mere decorative windows. These are poems in stained glass manifesting the resilient spirit of the East End which endured World War II. Another window by Margaret Rope in St Peters in the London Docks, completed in 1940, showed parishioners celebrating Midnight Mass at Christmas in a bomb shelter.

Margaret Edith Aldrich Rope was born in 1891 into a farming family on the Suffolk coast at Leiston. Her uncle George was a Royal Academician, and she was able to study at Chelsea College of Art and Central School of Arts & Crafts, where she specialised in stained glass. Unmarried, she pursued a long and prolific working life, creating over one hundred windows in her fifty year career, taking time out to join the Women’s Land Army in World War I and to care for evacuees at a hospital in North Wales during World War II, before returning to her native Suffolk at the age of eighty-seven in 1978.

Her nickname “Tor” was short for tortoise and she signed all her works with a tortoise discreetly woven into the design. Upon close examination, every window reveals hidden texts inscribed in the richly coloured shadows. So much thought and imagination is evident in these modest works executed in the magical realist style. They transcend their period as neglected yet enduring masterpieces of stained glass and I recommend you make your own acquaintance with the stylish work of Margaret Rope, celebrating the miraculous quality of the everyday.

St Leonard is portrayed in a moment of revelation outside St Leonard’s Church, Shoreditch, with Arnold Circus in the background and a London bus passing in the foreground

The lower panel of the St George window

A domestic East End scene from the lower panel of the St Anne’s window

This tortoise-shell cat is a detail from the panel above

The lower panel from the St Michael window

Mother Kate, Prioress of St Saviour’s and Father Burrows with his dog, Nipper, standing outside St Augustine’s in York St, now Yorkton St. In the right hand corner you can see the tortoise motif that Margaret Rope used to sign all her works.

Sisters of St Saviour’s Priory, portrayed in the lower panel of the St Margaret window, 1932

Margaret Rope’s St Paul and St Margaret, now in the entrance of Saviour’s Priory, Queensbridge Rd

Stained glass artist, Margaret Edith Aldrich Rope known as “Tor” (1891-1988)

You may also like to read about

So Long, Alfred Daniels

I feel privileged to have visited Alfred Daniels – known as the ‘Lowry of the East End’ – a handful of times in his final years. So, upon learning only this week of his death in 2015 in his ninety-second year, I could not let it pass unacknowledged. As Alfred might have said, ‘Better late than never.’

“I’m not really an East Ender, I’m more of a Bow boy,” asserted Alfred Daniels with characteristic precision of thought, when I enquired of his origin. “My parents left the East End, because they were scared of the doodlebugs and bought this house in 1945,” he explained, as he welcomed me to his generous suburban residence in Chiswick. Greeting me while dressed in pyjamas and dressing gown in the afternoon, no-one could have been more at home than Alfred in his studio occupying the former living room of his parents’ house. I found him snug in the central heating and just putting the finishing touches to a commission that his dealer was coming to collect at six.

I met Alfred at the point in life where copyright payments on the resale of works from his sixty-year painting career meant he no longer has to struggle. “I’ve done hundreds of things to make a living,” he confessed, rolling his eyes in amusement,”Although my father was a brilliant tailor, he was a dreadful business man so we were on the breadline for most of the nineteen thirties – which was a good thing because we never got fat …”

Smiling at his own bravado, Alfred continued painting as he spoke, adding depth to the shadows with a fine brush. “This is the way to make a living,” he declared with a flourish as he placed the brush back in the pot with finality, completing the day’s work and placing the painting to one side, ready to go. “The past is history, the future is a mystery but the present is a gift,” he informed me, as we climbed the stairs to the upstairs kitchen over-looking the garden, to seek a cup of tea.

Alfred had spent the morning making copious notes on his personal history, just it to get it straight for me. “This has been fun,” he admitted, rustling through the handwritten pages.

“My grandfather came from Russia in the 1880s, he was called Donyon, and they said, ‘Sounds like Daniels.’ My grandfather on the other side came from Plotska in Poland in the 1880s, he didn’t have a surname so they said ‘Sounds like a good man’ and they called him Goodman. My parents, Sam and Rose, were both born in the 1890s and my mother lived to be ninety-two. I was born in Trellis St in Bow in 1924 and in the early thirties we moved to 145 Bow Rd, next to the railway station. I can still remember the sound of the goods wagons going by at night.

One good thing is, I gave up the Jewish religion and thank goodness for that. It was only when I was twelve and I read about the Hitler problem that I realised I was Jewish. Fortunately, we weren’t religious in my family and we didn’t go to the synagogue. But I went to prepare for my Bar Mitzvah and they tried to harm me with Hebrew. We were taught by these Russians and if you didn’t learn it they bashed you. That put me off religion there and then. Yet when we got outside the Black Shirts were waiting for us in the street, calling ‘Here look, it’s the Jew boys!’ and they wanted to bash me too. Fortunately, I could run fast in those days.

My mother used to do all the shopping in the Roman Rd market. She hated shopping, so she sent me to do it for her in Brick Lane. It was a penny on the tram, there and back. But they all spoke Yiddish and I couldn’t communicate, so I thought, ‘I’d better listen to my grandmother who spoke Yiddish.’ I learnt it from her and it is one of the funniest languages you can imagine.

Although my parents were poor, my Uncle Charlie was rich. He was a commercial artist and my father said to him, ‘The boy wants to learn a craft.’ So Charlie got me a place at Woolwich Polytechnic to learn signwriting but I spent all day trying to sharpen my pencil. Then he took me out of the school and got me a job as a lettering artist at the Lawrence Danes Studio in Chancery Lane. It was wonderful to come up to the city to work, and his nephew befriended me and we went to art shops together to look at art books. We drew out letters and filled them in with Indian Ink, mostly Gill Sans. Typesetters usually got the spacing wrong but if you did it by hand you could get it right. It was all squares, circles and triangles.

When Uncle Charlie started his own studio in Fetter Lane above the Vogue photo studio, he offered me a job at £1 a week. Nobody showed me how to do anything, I worked it out for myself. He got me to do illustrations and comic drawings and retouching of photographs. At night, we went down in the tube stations entertaining people sheltering from the blitz. I played my violin like Django Reinhardt and he played like Stefan Grappelli, and one day we were recorded and ended up on Workers’ Playtime.

I had been doing some still lifes but I wanted to paint the beautiful old shops in Campbell Rd, Bow, so I went to make some sketches and a policeman came up and asked to see my identity card. ‘You can’t do this because we’ve had complaints you’re a spy,’ he said. It was illegal to take photographs during the war, so I sat and absorbed into memory what I saw. And the result came out like a naive or primitive painting. When Herbert Buckley my tutor at Woolwich saw it, he said, ‘Would you like to be a painter? I’ll put you in for the Royal College of Art. To be honest, I should rather have done illustration or lettering. At the Royal College of Art, my tutors included Carel Weight – he said, ‘I’m not interested in art only in pictures.’ – Ruskin Spear – ‘always drunk because of the pain of polio’ – and John Minton – ‘ a lovely man, if only he hadn’t been so mixed up.'”

Alfred was keen to enlist, “I wanted to stop Hitler coming over and stringing me up !” – though he never saw active service, but the discovery of painting and of his signature style as the British Douanier Rousseau stayed with him for the rest of his life. After Alfred left the East End in 1945, he kept coming back to make sketchbooks and do paintings, often of the same subjects – as you see below, with two images of the Gramophone man in Wentworth St painted fifty years apart.

With natural generosity of spirit, Alfred Daniels told me, “Making a painting is like baking a cake, one slice is for you but the rest is for everyone else.”

The Gramophone Man in Wentworth St, 1950

Sketchbook pages – Cable St, April 1964

Sketchbook pages – Old Montague St, March 1964

Sketchbook pages – Hessel St, April 1964

Sketchbook pages – Old Montague St & Davenant St, March 1964

Sketchbook pages – Fruit Seller in Hessel St, March 1964

Leadenhall Market, drawing, 2008

Billingsgate Market

Tower Bridge, 2008

The Royl Exchange, 2008

Crossing London Bridge, 2008

In Alfred’s studio

The Gramophone Man, Wentworth St, 2012

Alfred Daniels, Artist

You may also like to read about