At The Bishopsgate Bathhouse

Click here to book for my tours through July, August and September

Click here to buy tour gift vouchers for your family and friends

This extravagant domed orientalist edifice topped by the crescent moon is what you see above ground in the churchyard of St Botolph’s Bishopsgate, but it is the mere portal to a secret subterranean world beneath your feet.

These Turkish baths were built in 1895 by Henry & James Forde Nevill to a design by architect G Harold Elphick, and clad with interlocking ceramic tiles worthy of the Alhambra, designed by the architect and manufactured at Craven Dunnill in Shropshire. As you descend the spiral staircase to the larger, cavernous space below, note the ceramic motif of the hand of Fatima raised in blessing.

Yet the current edifice is simply the most recent in a series of bathhouses on this site dating back to 1817. In 1847, it was recorded that a certain Dr Culverwell was offering medicinal baths here. Around 1883, the baths were sold to Jones & Co who named them Argyll Baths and reconstructed them entirely, only for their work to be demolished ten years later and replaced by the building we see today.

In 1963, when Geoffrey Fletcher the author of ‘The London Nobody Knows’ passed by, the brass plate with the words Nevill’s Turkish Baths was still here even though it was merely in use as storage space by then. “Still eloquent of the vanished days when a corpulent company director would while a way an afternoon and a little avoirdupois in these exotic surroundings before taking himself to his green and pleasant villa in Denmark Hill”, he wrote.

In recent years, the grade II listed bathhouse has enjoyed a successful existence as a popular events venue but now it is imperilled by a redevelopment that would see a twenty-four storey office tower cantilevered above and underpinning below. The proposed tower over the Great Eastern Hotel nearby in Liverpool St potentially sets an alarming precedent for the possibility of constructing developments on top of listed buildings.

Readers are encouraged to write and object to this planning application which threatens to overwhelm the grade II listed bathhouse. Be sure to label your comment clearly as an ‘objection.’

Click here to visit the City of London planning website and make your objection

Developers’ proposal for a cantilevered tower that will overwhelm the historic bathhouse

Price list, c. 1885

c.1908

Drawing by Geoffrey Fletcher, 1963

The Boom Boom Club at the bathhouse

Click here to book an event at the Bishopsgate bathhouse

You may also like to read about

The East End In The Afternoon

Click here to book for my tours through July, August and September

Click here to buy tour gift vouchers for your family and friends

Yesterday I visited Clapton for a celebration of the life of Libby Hall (1941-2023) at her house in Ickburgh Rd where she had lived since 1967 with her husband Tony Hall (1936-2008). Today I publish this selection of Tony’s photographs.

There is little traffic on the road, children are at play, housewives linger in doorways, old men doze outside the library and, in the distance, a rag and bone man’s cart clatters down the street. This is the East End in the afternoon, as photographed by newspaper artist Tony Hall in the nineteen sixties while wandering with his camera in the quiet hours between shifts on The Evening News in Fleet St.

“Tony cared very much about the sense of community here.” Libby Hall, Tony’s wife, recalled, “He loved the warmth of the East End. And when he photographed buildings it was always for the human element, not just the aesthetic.”

Contemplating Tony’s clear-eyed photos – half a century after they were taken – raises questions about the changes enacted upon the East End in the intervening years. Most obviously, the loss of the pubs and corner shops which Tony portrayed with such affection in pictures that remind us of the importance of these meeting places, drawing people into a close relationship with their immediate environment.

“He photographed the pubs and little shops that he knew were on the edge of disappearing,” Libby Hall confirmed for me, ‘He loved the history of the East End, the Victorian overlap, and the sense that it was the last of Dickens’ London.”

In 1972, Tony Hall left the Evening News and with his new job came a new shift pattern which did not grant him afternoons off – thus drawing his East End photographic odyssey to a close. Yet for one who did not consider himself a photographer, Tony Hall’s opus comprises a tender vision of breathtaking clarity, constructed with purpose and insight as a social record. Speaking of her husband, Libby Hall emphasised the prescience that lay behind Tony’s wanderings with his camera in the afternoon. “He knew what he was photographing and he recognised the significance of it.” she admitted.

These beautiful streetscapes are from the legacy of approximately one thousand photographs by Tony Hall held in the archive at the Bishopsgate Institute.

Three Colts Lane

Gunthorpe St

Ridley Rd Market

Stepney Green

Photographs copyright © Libby Hall

Images Courtesy of the Tony Hall Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute

Libby Hall & I would be delighted if any readers can assist in identifying the locations and subjects of Tony Hall’s photographs.

You may also like to read

Tony Hall’s East End Panoramas

Jack London’s Photography

Click here to book for my tours through July, August and September

Click here to buy tour gift vouchers for your family and friends

Jack London took photographs alongside his work as a writer throughout his life, creating a distinguished body of photography that stands upon its own merits beside his literary achievements. In 1903, the first edition of his account of life in the East End, The People of the Abyss, was illustrated with over a hundred photographs complementing the text which were omitted in later reprints.

Homeless people in Itchy Park, Spitalfields

“In the shadow of Christ Church, Spitalfields, I saw a sight …

… I never wish to see again”

“Tottery old men and women were searching in the garbage thrown in the mud”

Drunken women fighting on a rooftop

Frying Pan Alley, Spitalfields

Before Whitechapel Workhouse in Vallance Rd

Casual ward of Whitechapel Workhouse

“Only to be seen were the policemen, flashing their dark lanterns into doorways and alleys”

Homeless sleepers under Tower Bridge

“For an hour we stood quietly in this packed courtyard” – Salvation Army Shelter

London Hospital, Whitechapel

In Bethnal Green

Working men’s homes, Wentworth St

A small doss-house

An East End interior

You may also like to read about

Letters From The SPAB Archive

Click here to book for my tours through July, August and September

Click here to buy tour gift vouchers for your family and friends

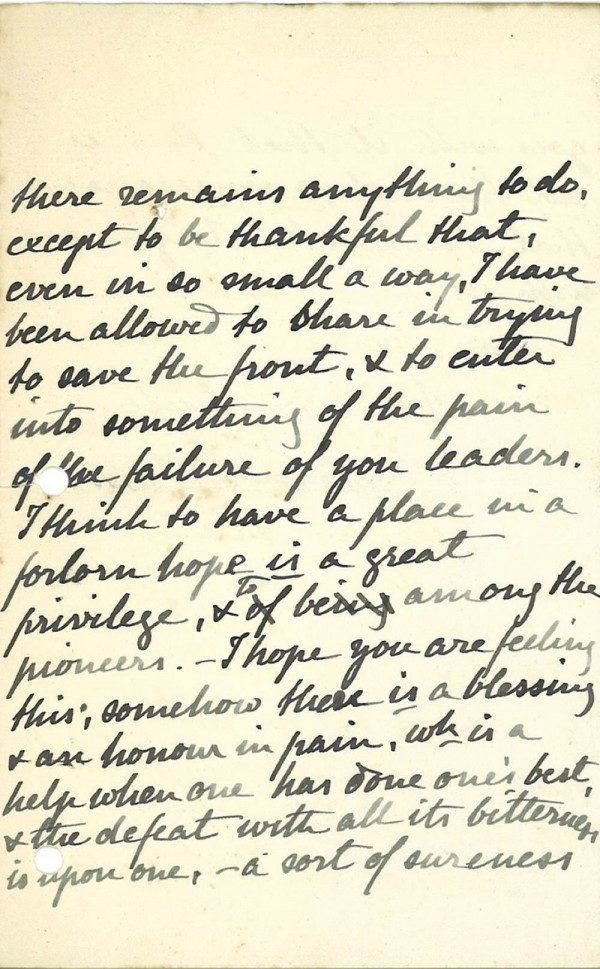

These are letters I found in the archive at the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in Spital Sq, confirming that my own modest involvement in campaigning has many noble precedents – as over the last one hundred and forty years, many writers and artists have sought to use their influence in a similar vein. Click on any of the images below to enlarge and read the text.

William Morris wrote to the Reverend H. West of the church at North Fordingham to express the Society’s disapproval about proposed building works and the letter encapsulates the founding principles of the SPAB in Morris’s own hand. They strongly objected to the Victorian passion for ‘restoring’ medieval buildings to an imagined state of antiquity. Believing this work to be pastiche and worse, Morris understood that it injured historic fabric as the guilty parties stripped and destroyed to achieve their own, largely inaccurate vision of what the building should have looked like. The word ‘restore’ is particularly significant as it implies putting back things that weren’t necessarily there in the first place. ‘Repair’ is still the Society’s operative word.

Reports of destructive activities came to the Society from many famous correspondents – here George Gilbert Scott ( Architect of St Pancras Station) writes of damage to the church at Mells in Somerset.

Edward Burne Jones write to Thackeray Turner (one of the earliest SPAB Secretaries) regarding problems at Worcester Cathedral on February 9th, 1897

William Holman Hunt wrote with great passion to Morris about his concerns over proposed ‘extensive repairs’ to the Great Mosque in Jerusalem. He writes with dismay that the gates have been painted “a vivid pea green that would disgrace a Whitechapel Shop front.”

Thanks to the concern of Charles Robert Ashbee, designer & founder of the School of Handicraft in Bow, the magnificent seventeenth century Trinity Almshouses still stand in Whitechapel today..

Octavia Hill, social reformer and one of the founders of the National Trust, wrote this grief struck letter about proposed alterations to the West Front of Peterborough Cathedral.

In his professional guise as an architectural surveyor, Thomas Hardy was a committed SPAB caseworker protecting churches in the West Country. In these hastily scribbled cards he writes in anguish over Puddletown Church which featured in Tess of the D’Urbevilles.

George Bernard Shaw wrote to the Society on 15th July 1929, enquiring over the wisdom of restoration at the church in Ayot St Lawrence.

John Betjeman wrote to ask for SPAB’s advice on the Unitarian Chapel, Newbury, which was built in 1697. Three months previously, it was sold to the YWCA who were raising funds to ‘repair’ it.

As a SPAB council member, John Betjeman wrote this comic note signed pseudonymously – indicative of the humour that prevailed.

Letters courtesy of Society for Protection of Ancient Buildings

You may also like to read about

Sandle Brothers, Manufacturing Stationers

Click here to book for my tours through July, August and September

Click here to buy tour gift vouchers for your family and friends

Today there is not even one stationer left but, not so long ago, there were a multitude of long-established manufacturing stationers in and around the City of London. Sandle Brothers opened in one small shop in Paternoster Row on November 1st 1893, yet soon expanded and began acquiring other companies (including Dobbs, Kidd & Co, founded in 1793) until they filled the entire street with their premises – and become heroic stationers, presiding over long-lost temples of envelopes, pens and notepads, recorded in this brochure from the Bishopsgate Institute.

The Envelope Factory

Stationery Department – Couriers’ Counter

A Corner of the Notepad & Writing Pad Showroom

Gallery for Pens in the Stationers’ Sundries Department

Account Books etc in the Stationers’ Sundries Department

Japanese Department

Picture Postcard & Fancy Jewellery Department

One of the Packing Departments

Leather & Fancy Goods Department

Books & Games Department

Christmas Card, Birthday Card & Calendar Department

A Corner of the Export Department

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

Swan Upping Season

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Since before records began, Swan Upping has taken place on the River Thames in the third week of July – chosen as the ideal moment to make a census of the swans, while the cob (as the male swan is known) is moulting and flightless, and before the cygnets of Spring take flight at the end of Summer. This ancient custom stems from a world when the ownership and husbandry of swans was a matter of consequence, and they were prized as roasting birds for special occasions.

Rights to the swans were granted as privileges by the sovereign and the annual Swan Upping was the opportunity to mark the bills of cygnets with a pattern of lines that indicated their provenance. It is a rare practice from medieval times that has survived into the modern era and I have always been keen to see it for myself – as a vision of an earlier world when the inter-relationship of man and beast was central to society and the handling of our fellow creatures was a important skill.

So it was my good fortune to join the Swan Uppers of the Worshipful Company of Vintners’ for a day on the river from Cookham to Marlow, just one leg of their seventy-nine mile course from Sunbury to Abingdon over five days. The Vintners Company were granted their charter in 1363 and a document of 1509 records the payment of four shillings to James the under-swanherd “for upping the Master’s swans” at the time of the “great frost” – which means the Vintners have been Swan Upping for at least five hundred years.

Swan Upping would have once been a familiar sight in London itself, but the embankment of the Thames makes it an unsympathetic place for breeding swans these days and so the Swan Uppers have moved upriver. Apart from the Crown, today only the Dyers’ and Vintners’ Companies retain the ownership of swans on the Thames and each year they both send a team of Swan Uppers to join Her Majesty’s Swan Keeper for a week in pursuit of their quarry.

It was a heart-stopping moment when I saw the Swan Uppers for the first time, coming round the bend in the river, pulling swiftly upon their oars and with coloured flags flying, as their wooden skiffs slid across the surface of the water toward me. Attended by a flotilla of vessels and with a great backdrop of willow framing the dark water surrounding them, it was as if they had materialized from a dream. Yet as soon as I shook hands with the Swan Uppers at The Ferry in Cookham, I discovered they were men of this world, hardy, practical and experienced on the water. All but one made their living by working on the Thames as captains of pleasure boats and barges – and the one exception was a trader at the Billingsgate Fish Market.

There were seven in each of the teams, consisting of six rowers spread over two boats, and a Swan Marker. Some had begun on the water at seven or eight years old as coxswain, most had distinguished careers as competitive rowers as high as Olympic level, and all had won their Doggett’s coat and badge, earning the right to call themselves Watermen. But I would call them Rivermen, and they were the first of this proud breed that I had met, with weathered skin and eager brightly-coloured eyes, men who had spent their lives on the Thames and were experts in the culture and the nature of the river.

They were a tight knit crew – almost a family – with two pairs of brothers and a pair of cousins among them, but they welcomed me to their lunch table where, in between hungry mouthfuls, Bobby Prentice, the foreman of the uppers, told me tales of his attempts to row the Atlantic Ocean, which succeeded on the third try. “I felt I had to go back and do it,” he confessed to me, shaking his head in determination, “But, the third time, I couldn’t even tell my wife until I was on my way.” Bobby’s brother Paul told me he was apprenticed to his father, as a lighterman on the Thames at fifteen, and Roger Spencer revealed that after a night’s trading at Billingsgate, there was nothing he liked so much as to snatch an hour’s rowing on the river before going home for an hour’s nap. After such admissions, I realised that rowing up the river to count swans was a modest recreation for these noble gentlemen.

There is a certain strategy that is adopted when swans with cygnets are spotted by the uppers. The pattern of the “swan voyage” is well established, of rowing until the cry of “Aaall up!” is given by the first to spot a family of swans, instructing the crews to lift their oars and halt the boats. They move in to surround the swans and then, with expert swiftness, the birds are caught and their feet are tethered. Where once the bills were marked, now the cygnets are ringed. Then they are weighed and their health is checked, and any that need treatment are removed to a swan sanctuary. Today, the purpose of the operation is conservation, to ensure well being of the birds and keep close eye upon their numbers – which have been increasing on the Thames since the lead fishing weights that were lethal to swans were banned, rising from just seven pairs between London and Henley in 1985 to twenty-eight pairs upon this stretch today.

Swan Upping is a popular spectator sport as, all along the route, local people turn out to line the banks. In these river communities of the upper Thames, it has been witnessed for generations, marking the climax of Summer when children are allowed out of school in their last week before the holidays to watch the annual ritual.

Travelling up river from Cookham, between banks heavy with deep green foliage and fields of tall golden corn, it was a sublime way to pass a Summer’s afternoon. Yet before long, we passed through the lock to arrive in Marlow where the Mayor welcomed us by distributing tickets that we could redeem for pints of beer at the Two Brewers. It was timely gesture because – as you can imagine – after a day’s rowing up the Thames, the Swan Uppers had a mighty thirst.

Martin Spencer, Swan Marker

Foreman of the Uppers, Bobby Prentice

The Swan Uppers of the Worshipful Company of Vintners, 2011

The Swan Uppers of 1900

The Swan Uppers of the nineteen twenties.

In the nineteen thirties.

The Swan Uppers of the nineteen forties.

In the nineteen fifties.

Archive photographs copyright © Vintners’ Company

You may also like to read about

Charles Skilton’s London Life

Click here to book for my tours through July, August and September

Now that the summer visitors are here and thronging in the capital’s streets and transport systems, I thought I would send you this fine set of postcards published by Charles Skilton, including my special favourites the escapologist and the pavement artist.

Looking at these monochrome images of the threadbare postwar years, you might easily imagine the photographs were earlier – but Margaret Rutherford in ‘Ring Round the Moon’ at The Globe in Shaftesbury Ave in number nine dates them to 1950. Celebrated in his day as publisher of the Billy Bunter stories, Charles Skilton won posthumous notoriety for his underground pornographic publishing empire, Luxor Press.

You may also like to take a look at