Truman’s London Keeper 1880 Export Stout

Ben Ott, Head Brewer at the New Truman’s Brewery

It was my privilege and delight to pop over to the new brewery at Hackney Wick last week and share a bottle of Truman’s London Keeper 1880 Double Export Stout wth Ben Ott, the Head Brewer. Unfortunately, he had almost emptied his glass by the time I came to take a picture, but I think Ben’s beatific smile gives an eloquent illustration of his pride and joy in this exciting new brew.

When Ben commenced brewing at Truman’s Brewery in Hackney Wick back in September, picking up from where the Brick Lane Brewery had left off twenty-four years ago, he realised that the first brew had to be special. For the first use of the original Truman’s yeast, that had been cryogenically preserved at the National Yeast Bank in Norwich, Ben adapted a recipe from a nineteenth century brewer’s record to create Truman’s London Keeper, brewing just two thousand bottles as trophies in celebration of this auspicious moment in East End brewing history

“It’s overwhelming when you go the archive, there’s quite a lot of really old Gyle books recording the brewing at Truman’s day by day,” Ben admitted to me, growing wide-eyed in wonder, “I looked for one that was one hundred years before my birth date but that turned out to be a Sunday, so then I looked at ninety-nine years before I was born – 19th April 1880 – and I found they were brewing a double export stout. I kept to the original gravity of 10/80 and I saw that there was so much pale malt, so much brown and so much black.” From this starting point, Ben researched the varieties of hops which were used at the time, seeking out modern strains with comparable qualities to compose his own recipe that would work for a contemporary taste.

If history was going to go into a bottle and be cherished, Ben decided champagne bottles should be employed, sealed with wax, and Baddeley Brothers – die-stampers and engravers who have been operating at the edge of the City of London since 1859 – were commissioned to print the labels. And James Morgan, the man responsible for the rebirth of Truman’s, signed every label alongside Ben as Head Brewer.

Truman’s London Keeper is a delicious brew for winter, warm and dark and tangy. If you love beer and the East End, then one of these bottles is the ideal keepsake – but maybe you will not be able to resist opening it for too long?

Each of the limited edition of two thousand bottles is signed by James Morgan, re-founder of Truman’s Beer and Ben Ott, Head Brewer

The Truman’s Gyle Book 0f 19th April 1880 that inspired Ben Ott to create Truman’s Keeper

Jack Hibberd of Truman’s Beer with Charles Pertwee of Baddeley Brothers

Printing the labels on the Original Heidelberg at Baddeley Brothers in Hackney

The last Truman’s Beer brewed in Brick Lane

Head Brewer, Ben Ott, with the first Truman’s Beer brewed at the new brewery in Hackney Wick

Baddeley Brothers photographs copyright © Colin O’Brien

Click here to get your bottle of Truman’s London Keeper 1880!

You may also like to read about

First Brew at the New Truman’s Brewery

Tony Jack, Chauffeur at Truman’s Brewery

Happy Birthday East End Trades Guild!

Celebrating the first Anniversary of the launch of the East End Trades Guild this week, Chairman Shanaz Khan (Proprietor of Chaat Bangladeshi Tea House), gives the Annual Report and James Brown has produced a print that you can buy to support the work of the Guild.

[youtube dg8TvQpkEng nolink]

This commemorative linocut print by James Brown, sold in support of The East End Trades Guild is available online from James Brown, Here Today Here Tomorrow and The Herrick Gallery.

Martin Usborne’s portrait of the founding of the Guild at Christ Church Spitalfields, a year ago.

You may also like to read about

The Rise Of The East End Trades Guild

The Founding of the East End Trades Guild

Irene Stride Remembers Spitalfields

Irene Stride

Irene Stride and her husband, Rev Eddy Stride, expected to be missionaries in Africa – but fate intervened. “At that time, all the Christian missionaries were being thrown out of China by the Communists and they were going to Africa, so the Missionary Society told us to ‘Seek home ministry!’ and we ended up in Spitalfields instead,” Irene recalled fondly and without regret, when I visited her recently in her home on the Isle of Dogs.

“It was a very poor area and people said to us, ‘What are you doing taking children to a place like that?’ because it was grim, but my husband said he couldn’t live with himself if we didn’t take what was offered,” she admitted to me, “We felt there was a need in those days. We went there in 1970 and stayed until 1989, when we retired.”

In spite of their reservations, Irene and her family quickly found themselves at home in Spitalfields. “After a few weeks, my family really loved it there, because they found they could go cycling everywhere, around the City and up to the West End,” Irene told me, growing enthusiastic in recollection.“When we came, the Jewish people and the Cockneys were moving out and the Bengalis were moving in,” she added, “now the Bengalis are moving out and people from the West End are moving in.”

“The church was shut up and was dangerous inside, so we used the hall in Hanbury St for services and the crypt was a shelter for alcoholics,” Irene explained, outlining the challenges she and her husband faced, “Dennis Downham was there before us, he had cleared out the crypt and put in a dormitory and a day room. It was run by a warden and men came into the crypt if he thought they had a chance of getting off alcoholism and some did, and some didn’t. My boys used to play snooker with the men, but they got upset when they saw them next day lying passed out in the street. The men used to come and knock on the Rectory door if they thought I would give them something – a cup of tea or a sandwich – so we did get to know them quite well.”

Spitalfields became the location that defined her husband’s ministry and, even today, it is the place for which Irene holds the strongest connection. “When I was twenty-three, Eddy and I were planning to be missionaries in Algeria, because Eddy had been there for three years during the war and he felt that he should go back as a missionary,” she confided to me, “So I went to the Mount Herman Missionary Training College in Ealing while he studied Theology in Bristol. His sister was one of my best friends and I knew him before he went to Africa. Then, while he was an engineer in Algeria, his sister kept talking about him. When Eddy came home, we clicked and it went from there.”

“After college in Bristol, we went to Christ Church, West Croydon, from there we moved to West Thurrock, South Purfleet and to St Mary’s Dagenham, and we were there for eight and a half years. That was where Eddy got his instruction to go to Spitalfields and off we went. I’m very glad I went there and my two boys met wonderful wives there. It was a very interesting place with all these characters and some real gems. My son Derek thinks it is the centre of the world for him!”

“Afterwards, we retired to Lincolnshire where we had friends and the family came for weekends but, once Eddy went to be with the Lord, I thought I had better move to be with the family, so I came back to London. I came here to the Isle of Dogs and I’m very happy here. I’ve got Stephen round the corner and Derek in Spitalfields, he takes me to Rainham Marshes and we go birdwatching every Monday.”

Irene Stride outside the Rectory, 2 Fournier St, summer 1975

The Stride family in the Rectory garden

Eddy Stride outside Christ Church, Spitalfields

Collecting the children at the school gates, Christ Church School, Brick Lane

From the Christ Church Crypt brochure of 1972 – “Outside a man is faced with vast impersonal hostels, sleeping rough, or seeking the shelter of the crypt”

Sandys Row, 1972

Brick Lane, 1972

Davenant House, the ‘new’ Spitalfields, 1972

The crypt passageway

A corner of the crypt

The sleeping area

Relaxing in the crypt, the snooker table

The crypt – sitting area

The crypt – kitchen

The crypt – dining room

The crypt – staff room

A resident of the crypt

Irene’s Daily Mirror cutting tells the story of a family who took refuge in the crypt during World War II

You may also like to read about

A View of Christ Church, Spitalfields

The Secrets of Christ Church, Spitalfields

James Parkinson, Physician of Hoxton

James Parkinson delivers an alehouse sermon (Image courtesy of Wellcome Library)

Eighteenth century maps show Hoxton – like Tottenham Court – as a small village surrounded by fields. To the south, only a few houses stood between it and Moor Fields, while open fields lay north and west, and to the east beyond Shoreditch, all the way to Bethnal Green.

James Parkinson, the man who would describe the disease which was posthumously given his name, was born in this hamlet in 1755. He grew up in Hoxton and, like his father before him, worked there as a Surgeon and Apothecary. Subsequently, Parkinson was followed in the same calling by his son and grandson.

He practised as a General Practitioner from his family home on the south-west corner of Hoxton Sq, which survived until the early twentieth century. Its successor on the same corner bears a plaque commemorating the Square’s most famous inhabitant. Occupied by a busy restaurant today, 1 Hoxton Sq, the site of his surgery and the house where he and his wife Mary had their six children, is no longer recognisable.

Parkinson lived all his life in Hoxton but he was far from parochial. He trained at the London Hospital and became an early member of the Medical Society of London, then housed near Fleet St – an important forum which spanned disciplinary boundaries, with members drawn from the fields of surgery, physic and pharmacy. He was also an early member of the Humane Society, devoted to the resuscitation of people injured in accidents and drownings, and a founder member of the Geological Society.

In those days, a good doctor might be called far and wide. Parkinson’s professional catchment area had a wide radius, focused on Hoxton but perhaps extending as far west as Charterhouse, as far south as the City’s edge, and as far east as Whitechapel and the scattered farms and market gardens of Hackney and Mile End. His home patch probably included most of the neighbourhood of Shoreditch and Spitalfields, including the neighbourhood that would later become famous from Arthur Morrison’s novel as ‘The Jago’ – the great slum which once existed around New and Old Nichol Streets, now buried underneath the Boundary Estate.

Doctors see and learn a great deal about their patients’ predicaments as well as their illnesses. Like many in his profession, before and since, Parkinson was exercised by the politics of the day which favoured the rich and left the poor to suffer. Politically, he was a reformer and a member of the London Corresponding Society, an organisation which pressed for social improvement at a time when criticism of the government was a dangerous endeavour.

The British government was jittery for a generation after the French Revolution and their informers infiltrated every political meeting. Parkinson got caught up in the ‘Pop-Gun Plot’, a non-existent conspiracy to kill the King dreamed up by a spy to implicate a number of London Corresponding Society members. For a time, several of them were under threat of execution if convicted, but Parkinson gave evidence to the Privy Council and it became clear, during the legal process, that the spy had fabricated the story.

The inhabitants of streets like Shoreditch High St, Pitfield St, Elder St and Fournier St would have seen Parkinson’s familiar figure passing to and fro, visiting the sick in their homes. Historically, the area was clustered with City almshouses and madhouses, some of which Parkinson served. But of those people whose disease he described, and which bears his name, we know little other than they lived in the vicinity of his surgery at 1 Hoxton Sq.

Parkinson saw enormous changes in his lifetime. Before he died in 1824, he witnessed the disappearance of the fields surrounding Hoxton and the retreat of the open country northwards. Very little now survives of the Hoxton he knew. In present-day Old St, which has encroached upon the ancient road bearing the lovely name of St Agnes le Clare, it is difficult to visualise the rural nature of the area as it was then. But vestiges of his time do survive. One house still standing on the opposite side of Hoxton Sq was among those built when the square was laid out in the sixteen-eighties and the old parish pump still stands in St Leonard’s churchyard, while the eighteenth century girls’ school rebuilt in 1802 still boasts its presence on the facade of a building at the junction of Kingsland Rd and Old St.

Among the monuments in the lovely church of St Leonard’s Shoreditch, many commemorating those who were likely patients of Parkinson, is a modern stone commemorating his life. It was erected by nursing staff at the former St Leonard’s Hospital on the Kingsland Rd, which originated as the Shoreditch Workhouse where Parkinson once served as Parish Surgeon, Apothecary and Midwife. His tombstone in the churchyard has disappeared and the site of his grave is unknown, yet Parkinson was a Church Warden at St Leonard’s and he knew its stones well.

Hoxton of 1747 from John Roque’s Map

1 Hoxton Sq, today

1 Hoxton Sq, c. 1900 (courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London)

Parkinson’s memorial stone

St Leonard’s Shoreditch

Title page of James Parkinson’s ‘Villager’s Friend & Physician’ 1804 (courtesy of the Wellcome Library)

You may also like to read about

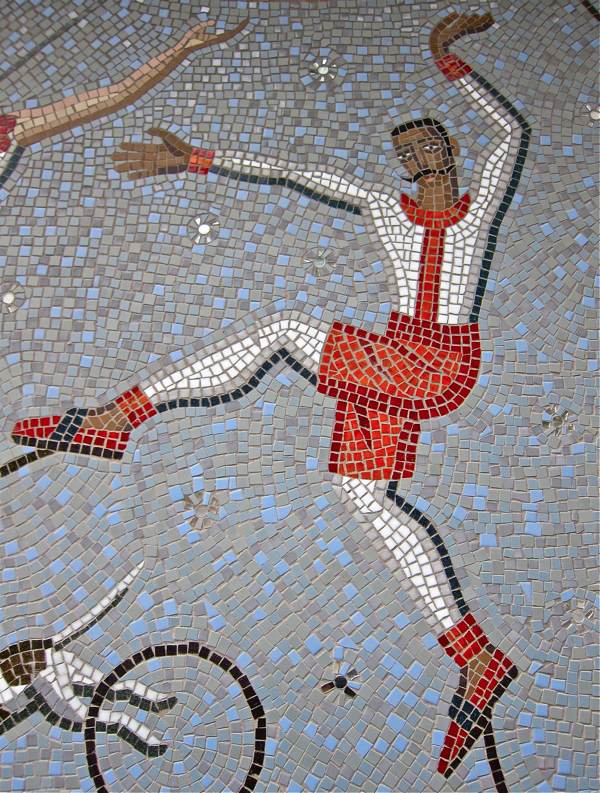

The Hoxton Varieties Mosaic

Walter Bernadin, master mosaic fixer & Tessa Hunkin, mosaic designer

The Mosaic Makers of Hoxton have been busy again and on Sunday I had the privilege to see their latest masterpiece unveiled upon the corner of Pitfield St and Old St. Celebrating the former Varieties Music Hall that opened nearby in 1870, the mural designed by Tessa Hunkin and realised by members of Hackney Mosaic Project, illustrates the glory days of live popular entertainment in Hoxton with colourful images of acrobats and performing dogs.

When I arrived, Walter Bernadin, a sprightly white-haired Italian, was up a ladder sponging off the excess grout to reveal Tessa’s lively design in its full glory for the first time. “I am a master mosaic fixing specialist, I’ve been doing it for fifty years,” he admitted to me when I brought him a cup of hot tea to warm his cold hands, “My father Giovanni was a mosaic fixing specialist before me, so I just took on from him. We come from Sequals in Italy, most of the mosiac fixers in London are from there.”

“My father was in espionage and he had been here as a prisoner of war in Mildenhall. Then, in the sixties, there was a lot of terrazzo going on in London, so he came over in 1964. He ran a mosaic gang of forty men and I helped them out on Saturdays from the age of twelve and that’s how I learnt my trade. They put it on bridges and underpasses to cover the concrete. I could take you all over London and show you work my father done.”

Building upon the success of the Shepherdess Walk Murals, the Hoxton Varieties Mosaic is another aesthetic triumph – installing joyful artwork in unloved corners of the neighbourhood and drawing everyone back to consider the meaning of the place. Even on a grim Sunday in November, a small crowd gathered in delighted excitement to admire the exuberance of the conception as a blank wall acquired a new life in Hoxton.

Walter Bernadin, Master Mosaic Fixing Specialist – “I could take you all over London and show you work my father done.”

Walter still carries his deed of apprenticeship with him in the van

Walter sponges off the surplus grouting to reveal Tessa’s finished design

Visit the Hoxton Varieties Mosaic at the corner of Pitfield St & Old St, N1.

You may also like to read about

The Loneliness Of Old London

Lost in Old London – Rose Alley, Southwark, c. 1910

When I first came to live in London, I had few friends, no job and little money, but I managed to rent a basement room in Portobello. For a year, I wandered the city on foot, exploring London without any bus fare. I think I never felt so alone as when I drifted aimlessly in the freezing fog in Hyde Park in 1983. As I walked, I used to puzzle how I could ever find my life in London. Then I went back and sat in my tiny room for countless hours and struggled to write, without success.

Today, I am often haunted by the spectre of my pitiful former self as I travel around London and, while examining the thousands of glass slides created by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society for educational lectures at the Bishopsgate Institute a century ago, I am struck by the lone figures isolated in the cityscape. The photographers may have included these solitary people to give a sense of human scale – but my response to these pictures is emotional, I cannot resist seeing them as a catalogue of the loneliness of old London.

In celebration of the publication of The Gentle Author’s London Album I am undertaking a peregrination around London performing my magic lantern show at diverse venues. This week’s stop is at Waterstones Bookshop in Covent Garden and I look forward to seeing you there on Thursday night.

THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S MAGIC LANTERN SHOW

Thursday 21st November 6:00pm at Waterstones, Garrick St, Covent Garden, WC2

I will be showing 100 pictures – including selected glass slides from a century ago, telling the stories and counterpointing them with favourite photographs of the unexpected wonders of London today.

Alone outside Shepherd’s Bush Empire, c. 1920

Alone at the Chelsea Hospital, c. 1910

Alone at the Natural History Museum, c. 1890

Alone at the Tower of London, c. 1910

Alone at Leg of Mutton Pond, Hampstead, c. 1910

Alone in the Great Hall at Chelsea Hospital, c. 1920

Alone outside St Lawrence Jewry, 1908

Alone in Bunhill Fields, c. 1910

Alone in Hyde Park, c. 1910

Alone at the Guildhall, c. 1910

Alone at Brooke House, Hackney, 1920

Alone on Hampstead Heath, c. 1910

Alone in Thames St, 1920

Alone at the Orangery, Kensington Palace, c. 1910

Alone in the Deans Yard at Westminster Abbey, c. 1910

Alone at Hampton Court, c. 1910

Alone at the Houses of Parliament with the statue of Richard I, c. 1910

Alone in the tiltyard at Eltham Palace, c. 1910

Alone at Southwark Cathedral, c. 1910

Alone outside Carpenters’ Hall, c. 1920

Alone outside Jackson Provisions’ shop, Clothfair, c. 1910

Alone outside Blewcoat School, Caxton St, c. 1910

Alone on the Victoria Embankment, c. 1910

Alone outside All Saints Chelsea, c. 1910

Alone at the Albert Hall, c. 1910

Glass slides courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

Take a look at

The Lantern Slides of Old London

The High Days & Holidays of Old London

The Fogs & Smogs of Old London

The Forgotten Corners of Old London

The Statues & Effigies of Old London

Lewis Lupton In Spitalfields

In the spring of 1968, artist Lewis Frederick Lupton came to Spitalfields and submitted this illustrated report on his visit to the Christ Church Spitalfields Crypt Newsletter.

Interior of Christ Church, Spitalfields, 1968 – without galleries or floor

On Ash Wednesday 1968, I set off at eleven for Spitalfields to see the Rev. Dennis Downham about his work among alcoholic vagrants. Walking up the road from the Underground Station, I saw a man very poorly dressed, his face a pearly white, obviously ill. Then came a tramp, as lean, dirty, unkempt, bearded and ragged as any I have seen. This was a district where there was real poverty.

The Rectory was a substantial Georgian house such as one sees in many a country village. The study overlooked a small garden and the east end of the church, where plane trees grew among old tombstones.

After lunch, we went out to see something of the parish. The first person we encountered was a fine-looking young American in search of his ancestors, who asked for the parish registers. After directing him to County Hall, we crossed over into a narrow street between tall old brick houses with carved and moulded eighteenth century doorways. Out of one of these popped a little Jewish man with a white beard, black hat and coat.

Round the corner in Hanbury St, the Rector unlocked (“You have to be careful about locks here”) the door of a building in which the church now worships ( “Christ Church itself needs a lot spending in restoration before it can be used again”). The building now employed once belonged to a Huguenot church, of which there were seven in the parish, and still has the coat of arms granted by Elizabeth I carved above the communion table.

Thousands of French Protestants found a refuge from persecution in this parish. The large attic windows belonging to the rooms where they kept their looms may still be seen in many streets and the street names bear record of the exiles – Fournier St, Calvin St etc

Crossing Commercial St, we came across a charming seventeenth century shop in a good state of preservation. Its fresh paint made it stand out like a jewel from the surrounding drabness.

A stone’s throw further on, photographs pasted in a window advertised the attractions of one of the many night clubs in the area.

Opposite a kosher chicken shop, one of a the staff – a Jewish man with a beard, black hat and white coat was throwing pieces of bread to the pigeons.

Round the corner, we plunged into an offshoot of the famous Petticoat Lane which forms the western boundary of Spitalfields.

Turning eastwards, we tramped along the broken pavements of a narrow lane running through the heart of the district. It seemed to contain the undiluted essence of the parish in its fullest flavour, a mixture of food shops, warehouses, prison-like blocks of flats, derelict houses and bomb-sites. “There are twenty-five thousand people living in my parish. It is the only borough in central London which has residential life of its own,” revealed the Rector.

Christ Church stands out like a temple of light in the surrounding squalor. Designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, its scale is much larger than life and the newly-gilded weathervane is as high as the Monument. “I climbed up the ladders to the top last year when steeplejacks were at work upon it,” commented the Rector.

Christ Church stands out like a temple of light in the surrounding squalor. Designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, its scale is much larger than life and the newly-gilded weathervane is as high as the Monument. “I climbed up the ladders to the top last year when steeplejacks were at work upon it,” commented the Rector.

Were it not for the brave work which has been begun in the cellars, the building would only be a proud symbol of the Faith, no more.

Down the steps, to the left of the porch, there is a reception area with an office and a clothes store.

One sleeping fellow had a tough expression. “False nose,” said the Rector, “he had his real one bitten off in a fight.” The central area is devoted to the work for which the crypt was opened. Except for a billiard table, it is like a hospital ward, mainly taken up with beds on which the patients rest and sleep.

Yet, a crypt is crypt and the lack of daylight is a handicap but, with air-conditioning throughout, spotless cleanliness and a colour scheme of cream and turqoise blue, the cellars of Christ Church have been turned into a refuge which offers help and hope to those of the homeless alcoholics who have a desire to be rescued from their predicament. – L.F.L.

You may also like to read about