These are just a few letters I found in the archive at the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in Spital Sq, confirming that my own modest involvement in the successful campaign to save the Marquis of Lansdowne has many noble precedents, as over the last one hundred and thirty years, many writers and artists have sought to use their influence in a similar vein. Celebrating National Explore Your Archive Week, it is my pleasure to publish these letters for the first time – click on any one of the images below to enlarge and read the text.

William Morris wrote to the Reverend H. West of the church at North Fordingham to express the Society’s disapproval about proposed building works and the letter encapsulates the founding principles of the SPAB in Morris’s own hand. They strongly objected to the Victorian passion for ‘restoring’ medieval buildings to an imagined state of antiquity. Believing this work to be pastiche and worse, Morris understood that it injured historic fabric as the guilty parties stripped and destroyed to achieve their own, largely inaccurate vision of what the building should have looked like. The word ‘restore’ is particularly significant as it implies putting back things that weren’t necessarily there in the first place. ‘Repair’ is still the Society’s operative word.

Reports of destructive activities came to the Society from many famous correspondents – here George Gilbert Scott ( Architect of St Pancras Station) writes of damage to the church at Mells in Somerset.

Edward Burne Jones write to Thackeray Turner (one of the earliest SPAB Secretaries) regarding problems at Worcester Cathedral on February 9th, 1897

William Holman Hunt wrote with great passion to Morris about his concerns over proposed ‘extensive repairs’ to the Great Mosque in Jerusalem. He writes with dismay that the gates have been painted “a vivid pea green that would disgrace a Whitechapel Shop front.”

Thanks to the concern of Charles Robert Ashbee, designer & founder of the School of Handicraft in Bow, the magnificent seventeenth century Trinity Almshouses still stand in Whitechapel today..

Octavia Hill, social reformer and one of the founders of the National Trust, wrote this grief struck letter about proposed alterations to the West Front of Peterborough Cathedral.

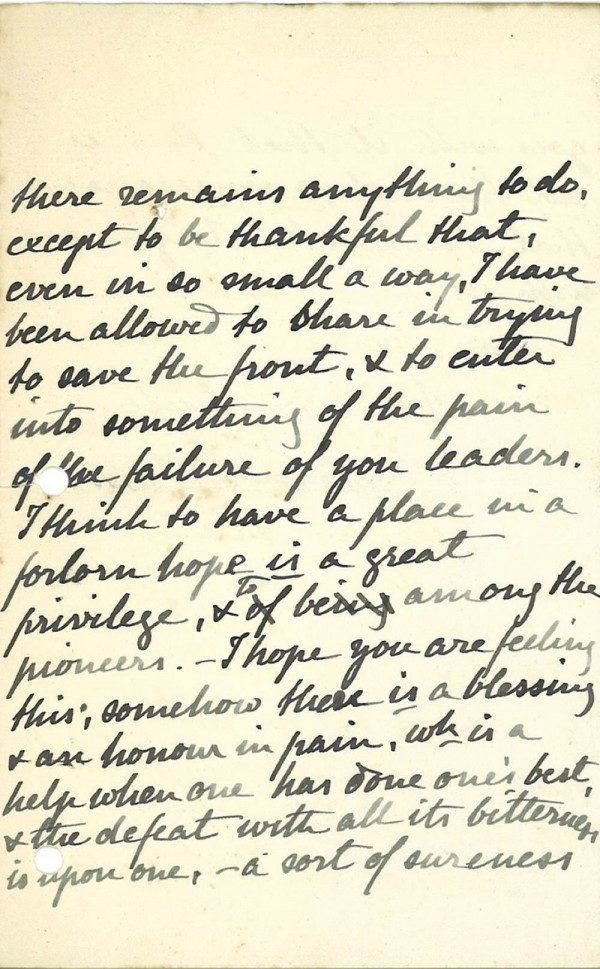

In his professional guise as an architectural surveyor, Thomas Hardy was a committed SPAB caseworker protecting churches in the West Country. In these hastily scribbled cards he writes in anguish over Puddletown Church which featured in Tess of the D’Urbevilles.

George Bernard Shaw wrote to the Society on 15th July 1929, enquiring over the wisdom of restoration at the church in Ayot St Lawrence.

John Betjeman wrote to ask for SPAB’s advice on the Unitarian Chapel, Newbury, which was built in 1697. Three months previously, it was sold to the YWCA who were raising funds to ‘repair’ it.

As a SPAB council member, John Betjeman wrote this comic note signed pseudonymously – indicative of the humour that prevailed.

Letters courtesy of Society for Protection of Ancient Buildings

You may also like to read about

Romilly Saumarez Smith & Lucie Gledhill, Jewellery Makers

Romilly Saumarez Smith & Lucie Gledhill

Sequestered in a cavernous old house in Stepney, two women work together to make jewellery under the name of Savage & Chong, combining their mothers’ maiden names to create a new identity for themselves. “We chose the names because they sound good together and it’s a bit of both of us.” revealed Lucie modestly, yet I discovered that the nature of their work reflects their different life histories in complex and unexpected ways.

“I used to make jewellery but I was no longer able to do it when I became paralysed,” confided Romilly with startling candour, “Yet, after a four or five year break, I was persuaded I should try to find someone I could work with closely and make jewellery again.”

We were sitting in an eighteenth century panelled room, painted in tones of red sandstone, as the Winter sunlight streamed in at a low angle and I realised I had entered a private world in which these two women pursued their activities with a quiet intensity, forged from a unique working relationship.

“We met two years ago,” continued Lucie helpfully, explaining how she began by remaking pieces of jewellery that Romilly had made as a way to advance their shared understanding.“What was exciting was that when Lucie made something and showed it to me, it felt like I had made it,” interposed Romilly, widening her eyes in wonder at this revelation. “We do things in the same way,” admitted Lucie simply, confirming the intimate rapport they discovered as jewellery makers and, consequently, as human beings.

“I still go through the process of making it in my head,” outlined Romilly, justifying her title as a jewellery maker,“Because I’ve done it myself, I understand a lot of techniques – but Lucie has refined my work and made it better.”

Lucie trained as a jewellery maker and graduated from the Royal College of Art in 2009, whereas, for Romilly, the journey was more circuitous. “I never trained as a jeweller, I spent most of my life as a bookbinder, so I didn’t have any formal idea of how things should be done, I made it up,” Romilly confessed to me, “I was bookbinder for twenty-five years, then I started using metal as bosses and clasps, and I really enjoyed it. I learnt to solder and made a pair of copper earrings, and I was so excited, I decided to take a sabbatical from bookbinding – but once I started making jewellery, I didn’t want to go back.”

“We’ve set ourselves rules,” announced Lucie, introducing the jewellery they have created as Savage & Chong, “everything we do is handmade and everything we do is made here. Everything is silver or gold and it is not plated or cast.”

There is a subtle undemonstrative beauty to this work, which plays upon varied tones of silver and gold enhanced by oxidising or heat-treatment – while the forms evoke both the natural world, of seedpods and shells, and the paraphernalia of textiles, threads, buttons and lace bobbins. Rather than jewellery for display, these are pieces designed to give enduring pleasure to the wearer, discreet keepsakes to cherish.

Neither Lucie or Romilly would have made this work alone, it is the outcome of their combined sensibilities, abilities, judgement and experience. “I felt a great determination not to give up my life which I loved, and I still do,” Romilly assured me. Yet, in winning back her art, she has boldly ventured into a new creative territory with Lucie and it gives their work a distinctive quality that is unique and compelling.

Woven Ring

Lucie Gledhill

Buttoned-up ring

Cluster pendant

Tattoo Ring

Romilly Saumarez Smith

Portraits copyright © Lucinda Douglas Menzies

The East End Preservation Society

Paul Pindar’s House in Bishopsgate, demolished 1890

Old buildings have been going down like nine pins in the East End recently. They are the latest sad additions to a catalogue of loss that stretches back over more than a century, inducing sufficient grief among the populace to fill the Thames with tears. Yet it is not our nature to be defeated and, upon each occasion, there have been those who have stood up and objected. Many of the most-loved old buildings that survive today owe their existence to such brave souls.

Until now, small groups of people have come together to save a particular building – but the accelerating sequence of losses in recent years, combined with some monstrous developments looming in the immediate future and the failure of the public consultation process, calls for collective action.

Thus I write today to conjure into existence The East End Preservation Society as a means to bring together everyone that cares about the East End and is concerned about the future of its built environment. If we can work collectively in large numbers, we can have a stronger influence upon the culture of development that threatens old buildings and be more powerful in our individual campaigns to save them.

Less than a month ago, Mayor of London, Boris Johnson gave his approval to a plan that reduces the venerable structure of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital for Children in Hackney, which represents a noble history of philanthropic service, to a mere facade upon an overblown commercial housing development of questionable quality. A year ago, the Mayor of London overruled a unanimous vote by the elected members of Tower Hamlets Council to save the Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange, and gave developers licence to replace the building with an office block and shopping mall of generic design, upon which the stone facade of the current building will sit as a painful reminder of the distinctive edifice that once stood there.

In this climate, where democratic decision-making is being undermined and public consultation reduced to a cynical public relations exercise, the rescue of The Marquis of Lansdowne from intended demolition by the Geffrye Museum was a joyful exception to the rule, proving that strength of public feeling can still be successful in saving an old building.

So I ask you to come to the Main Hall at the Bishopsgate Institute on Wednesday 27th November at 6:30pm for the launch of The East End Preservation Society.

Spitalfields resident, writer and campaigner, Dan Cruickshank has been invited to address the assembly. We will be showing images of notable buildings that have been lost and buildings that have been saved in the past. Will Palin, ex-secretary of Save Britain’s Heritage, will be assessing the recent history of destruction and introduce reports upon current developments at the Bishopsgate Goodsyard and in Whitechapel that threaten the East End.

Most importantly, we shall be suggesting ways that you can get involved and proposing how we can become organised to make an effective response to the current crisis. If the future of the East End is important to you, you need to be there.

Spital Sq – Within living memory, this was one of London’s most beautiful squares but it was sacrificed to road widening and commercial developments at the end of the last century, and only one eighteenth century house survives today.

The Jewish Maternity Hospital in Underwood Rd was designed by John Myers in 1911. This Arts & Crafts style cottage with its elegant crow-stepped gables was reminiscent of a streetscape by Vermeer and, athough it had lost its diamond-paned leaded windows, it retained its original doors and ironwork.

In January 2012, this is what became of the nursing home where Alma Cogan, Lionel Bart, Arnold Wesker and many thousands of Jewish East Enders were born.

Next year, this stone facade is all that will remain of Sydney Perk’s 1927 Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange when the new office block and shopping mall are constructed behind it.

Magnificent staircases at the Fruit & Wool Exchange will be trashed in the forthcoming demolition.

Only the facade of the Queen Elizabeth Children’s Hospital on the Hackney Rd will survive if the current plan goes ahead.

The oldest part of the Queen Elizabeth Children’s Hospital in Goldsmith’s Row is slated for demolition.

After Hackney Council refused permission for demolition in response to a public campaign, The Marquis of Lansdowne is to be restored as an integral part of the Geffrye Museum’s proposed new extension.

Launch of The East End Preservation Society in the Main Hall at the Bishopsgate Institute, Wednesday 27th November 6:30pm

Follow The East End Preservation Society on twitter @EastEndPSociety

You may also like to read about

Remembering The Queen Elizabeth Children’s Hospital

The Pub That Was Saved By Irony

So Long, Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange

Antony Cairns’ East End Pubs

When – in the midst of my photographic odyssey around East End watering holes – I discovered Antony Cairns‘ series of pub portraits, I realised I had found a kindred spirit. His soulful photographs manage to record the death and evoke the life of these lost hostelries simultaneously.

An East Ender who studied photography at the London College of Printing in the nineties, Antony printed these intriguing pictures using the Van Dyke Brown process which was commonly used at the end of the nineteenth century when these pubs were in their prime.

The Albion, Bow Common – (1881-2005)

The Railway Arms, Sutton St – (1881-2001)

The Conqueror, Austin St/Boundary St – (1899-2001)

The Rose, Woolwich

The Flying Scud, Hackney Rd – (1874-1994)

The Crown & Cushion, Market Hill, Woolwich – (1840-2008)

The Victoria, Woolwich Rd, Charlton – (1881-?)

The Tidal Basin, Canning Town – (1862-1997)

The Marquis of Lansdowne – (1838- 2000 & now to be restored)

Photographs copyright © Antony Cairns

You may also like to take a look at

Alex Pink’s East End Pubs, Then & Now

Martin White, Textile Consultant

Today it is my pleasure to publish the story of Martin White, one half of the charismatic partnership with Philip Pittack that is Crescent Trading, operators of Spitalfields’ last cloth warehouse.

Martin White, aged two in 1933

“That’s the difference between Philip & me,” explained Martin White, articulating the precise distinction between himself and his business partner Philip Pittack, “He’s a Rag Merchant, whereas I am a Textile Consultant. I understand textiles, I know about suitings and have been dealing in them since 1946. Our different specialities complement each other.”

Famous for his monocle and pearl tiepin, as well as his unrivalled knowledge, Martin White is one half of the duo known as Crescent Trading, possessing more than one hundred and twenty years of experience in the business between them. While their continuous comedy repartee has won them a reputation as the Mike & Bernie Winters of the textile trade.

In particular, Martin is known for his ability to make an offer on a parcel of textiles on sight. “Very few people know how to do it,” he admitted to me. “These days, Philip & I go on a buying trip twice a year, but in the past I used to go buying every day.” Martin’s story reveals how he acquired his remarkable knowledge of textiles, developing an expertise that permits him obtain the quality fabrics for which Crescent Trading is renowned.

“My father, William White, was a leather merchant but he also had some boot repair shops and, because he was a bit of mechanic, he rebuilt boot repairing machines. And that’s what he wanted me to go into. We lived in a very nice house in Shepherd’s Hill, Highgate, but unfortunately my father was diabetic who didn’t believe in conventional medicine. He was a herbalist and he became very ill in his forties and died at forty-six.

I started work at fourteen for my two uncles, Joe Barnet & Mark Bass (known as Johnny,) at their shop in Noel St off Berwick St in 1946. I was a little boy who didn’t know anything and in those days fabric was rationed and very hard to come by. Joe used to go up north and he had contacts in Manchester who used to get him stuff from the mills. It was a tiny shop and everything we got we sold immediately. They were making thousands every week and I was getting two pounds a week for carrying the fabric in and out. I used to like touching the fabric and that’s how I learnt about it.

While I was there, my father died and another of my uncles, David Bass, came to see my mother and he said he would take me to work for him and give me a wage, so she wouldn’t have to worry about me. But when the two uncles I was already working for heard this, Joe Barnet sent his wife Zelda to my mother to say that, if I worked for David, I would take all their customers from Noel St and it would ruin their business. So Joe Barnet told my mother he would look after me. He had just formed an association with a government supply business in Bethnal Green and he asked me to go down there and watch because he didn’t trust them, and that was my job.

So the first Friday came and he gave me five pounds, that was my wages. The following week, I found a parcel of cloth for sale in Brick Lane and I bought three thousand yards at a shilling a yard and I sold it for three shillings and sixpence a yard. The next Friday, Joe gave me fifteen pounds but I realised I had no chance of furthering myself with him, so I left and started working with another boy of my own age, Daniel Secunda. We were fifteen years old. We had no premises. We used to stand by the post at the corner of Berwick St, and people came to us with samples and goods to sell. We took the samples and sold them, and we made a good living between the two of us. We were young and we were carefree.All the money we earned, we spent it. We were happy. We went out every night. And that lasted for about three years, before the business got hard when rationing ended.

Then I met a guy who wanted to go into business properly with us, Pip Kingsley. He took premises in Berwick St and formed P. Kingsley & Co. After a while, it became apparent that while Danny was a very good-looking and likeable fellow, I was the worker out of the two of us. So Kingsley got rid of Danny and rehired an old job buyer who had retired, Myer King, and we started working together. He was an Eastern European, a very big man who couldn’t read or write. He had the knack of job buying ‘by the look.’ He’d go into a factory and make an offer for everything on the spot. This method of buying was different to anything I had ever seen but it worked. By working with him, I learnt what to do and what not do. And that knowledge was the basis of how I did business from then on.

I was happy working with Kingsley & Myer, but then I met my wife to be, Sheila, and I decided that I wanted my share of the money that my father had left in trust for my younger brother Adrian and me when we were twenty-one. I wanted to get married, and Sheila had been married before and she had a little boy. She was very beautiful. She’s eighty-five and she’s still beautiful.

My brother Adrian was known as Eddie and, at the age of eleven while my father was dying, he contracted sugar diabetes, so they were both in hospital. In the next bed to him was George Hackenschmidt, a boxer who had done body-building and my brother became interested in this. It was a very sad thing, my dad died when they were both in hospital and an uncle said to Eddie, ‘When you get out, I’ll buy you anything you want,’ to make him feel better. So Eddie said, ‘I want a set of weights.’

It was back in 1945, Eddie was twelve and he got one hundred pounds worth of weights and equipped a gym in our garage, and he started doing these workouts in the American magazines that George Hackenschmidt had given him. Eventually, he became Charles Atlas’ body. They would take the head of Charles Atlas and put it on a photo of my brother in the adverts for body-building.

When we broke my father’s trust fund, Eddie was twenty-one and we each received eight hundred pounds. My brother only lifted weights and sat in the sun, so I said to him, ‘What are you going to do with this? Give it to me and we’ll be partners, and I’ll do all the work and you can sit in the sun.’

Now, I wanted to get married to Sheila and her father was a textile merchant but her family didn’t like who I was. One of them was A. Kramer who happened to be Dave Bass’ solicitor and he phoned me up to warn me off her. So I told him what he could do, and Sheila and I got married in a registry office in 1955. Sheila’s little boy was four and her father, Lou Mason, didn’t want him to suffer, so he came to see me at my business and I showed him what I was buying.

Then he approached me one day and asked if I was interested in looking at a parcel of goods he had found in Wardour St at a lingerie company called Row G. So I went to see the parcel and made an offer of seven hundred pounds on sight. Lou said, ‘We don’t do business that way,’ and I said, ‘I’ll do it how I want to do it.’

The owner said, ‘No,’ but two weeks later I went back. He took the seven hundred pounds and it was all sold within two weeks for eighteen hundred pounds. My father-in-law said, ‘I’ve never seen anything like this. It’s wonderful, why don’t you come and work with me?’ I couldn’t say, ‘No,’ to my father-in-law. There was no option. I said to my brother, ‘We’ll have to part company and I’ll give you your money back.’ He never forgave me.

The very first deal that came along was Cooper & Keyward, they had a lot of rolls of suiting and it came to two thousand pounds. But when I asked my father-in-law for the money to buy it, he said, ‘I’m a bit short this week.’ I just about had the two thousand pounds so I laid out the money myself and took the goods, and my father-in-law was able to sell it to his customers. On Friday, I said to him, ‘I need forty pounds to take my wife out,’ and he said, ‘We don’t spend money that way!’ So I fell out with my father-in-law. It turned out, he didn’t have the money to pay me because his business was going bankrupt.

I went round to get my goods which were in the basement of a shop in Berwick St and my mother-in-law was in the shop. A cousin came out and said, ‘You’re going to kill her, can’t we meet at the weekend and sort this out?’ At the meeting, my father-in-law accused me of being a liar but my wife’s aunt, Joyce, knew him and said to me, ‘I believe you.’ I never was a liar. She said to me, ‘If I lend you a thousand pounds, can you make a living?’

In Berwick St, Johnny Bass was trying to sell his stock at the shop where I had started work. The Noel St shop was full of fabric and he’d offered it to several people but no-one could assess what was there. He wanted four thousand pounds yet, because of my knowledge, I was able to cut a deal for two thousand four hundred pounds. It was Friday night and he said, ‘Give me some money.’ He’d just come of out of the bookmakers and he was penniless. I had a hundred pounds on me, so I gave him that and I had to find the rest of the money.

I went to get it from Joyce but she was in hospital. So I visited her and she said, ‘My husband Bert will get the money for you,’ and on the Monday he came with me to pay Johnny. Joyce had a property in Mansell St and I filled it up with the fabric and started selling it every day from there. Joyce was coming over to collect money from me in her handbag. She was charging me one hundred pounds a week rent plus interest, so I realised she thought I was working for her now but it wasn’t a partnership in my eyes and I wouldn’t go along with it.

I told her I wanted premises in Great Portland St and I needed money for that. It was agreed and that’s what we did. It was called the Robert Martin Company – Sheila’s son was called Robert. I got Daniel Secunda back to work with me. It was 1956, I had my own shop at last. And that’s how I became a textile merchant.”

Aged two, 1933

Aged three, 1934

Aged five in 1936

At school in Highgate, 1936

At a family wedding in September 1939. On the left are William & Muriel White, Martin’s parents. Beside them is Joe Barnet, Martin’s first employer, and his wife Zelda.

Martin’s brother Adrian (known as Eddie) who became the body of Charles Atlas

Martin’s brother Adrian (known as Eddie) who became the body of Charles Atlas

Martin White & Danny Secunda, his first working partner in 1956

Martin White & Philip Pittack, Crescent Trading Winter 2010

Crescent Trading, Quaker Court/Pindoria Mews, Quaker St, E1 6SN. Open Sunday-Friday.

You may also like to read about

The Return of Crescent Trading

Bob Paice, Warden Of The Jewel House & Pearly Pride

Bob Paice, in his livery as Warden of the Jewel House at the Tower of London

Bob Paice, in his suit as a Pearly Pride

On Friday, Bob Paice’s last day as Warden of the Jewel House at the Tower of London after seventeen years, Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I went down to witness Bob’s transformation as he swapped the livery of his former employment for the attire of his new identity as a Pearly Pride. Yet, although the metamorphosis was seemingly accomplished by the simple matter of a change of clothing, we discovered that this was actually the culmination of an evolutionary process which began years ago.

Overseeing Bob’s emergence as a Pearly were Larry & Doreen Golding. “We’re his mentoress and his mentor,” explained Doreen proudly, “We’re the Pearly King & Queen of Bow Bells and we’re Freemen of the City of London.” Larry & Doreen revealed that ,throughout his years at the Tower, Bob organised social events for the residents – discos, barbecues and Christmas parties – raising hundreds of thousands for St Joseph’s Hospice and so, when the Pearlies came to collect the cheques as patrons of the hospice, they recognised Bob’s potential.

“People ask us why do you dress up like this?” Doreen queried rhetorically, “The reason is, ‘We’re charity workers.'” Originating in the nineteenth century as a self-help organisation for deprived families of costermongers, these days the Pearlies devote themselves to fundraising for a wide range of charities.

“When Larry invited me to the Pearly Harvest Festival, I did the parade in my Jewel House Warden livery,” Bob recalled fondly, “After the service, we always have something to eat and drink at the pub, and I was having a cigarette outside when he said, ‘It’s about time you joined us.’ So I said, ‘Once I’ve finished this, I’ll be in,’ but he said, ‘No, I meant become a Pearly.’ That was about three years ago and then, at last year’s Pearly Parade, he said, ‘You’ve got no excuse because you’re retiring.’ I said, ‘Where do I get the buttons?'”

“People like the idea of dressing up as a Pearly , but you can be standing outside for hours in the cold and you can’t put on a coat, it’s not glamorous,” admitted Larry, speaking as the voice of experience at eighty-six years old, “You can’t clean the suit either and it can get quite sweaty and smelly in the summer. You have to sponge it down, dry it with a hair dryer and hang it out.”

“I bought this suit in Stratford for a hundred quid,” confessed Bob, “And it has four thousand, three hundred and fifty buttons. It took me six months to get this far and already it weighs eight pounds. I sewed them all on myself with a little bit of help.”

Yet, in spite of Bob’s eager anticipation of his new role, it was also a moment to look back. “I was born and bred in Stratford, and I’ve lived my whole life there,” he confided to me, “My first job at fifteen years old was at Clarnico Sweets in Waterden Rd. When you started you got free bags of sweets but then you got sick of them. I don’t have a sweet tooth. I remember my first pay packet, I got one pound and fifty pence a week. So I gave a pound to mum and had fifty pence spending money, but I always had to ask her for a sub on Wednesday to get me through ’til Friday. Then I worked for the Bass Brewery in Silvertown, I worked on the vat floor and I went out as a van boy until I was made redundant after sixteen years.

I applied for this job when I saw an advert in the evening paper. I remember the interview, there were five of them on one side of a long table and an empty chair on the other side with a glass of water, so I thought, ‘That’s where I’m sitting.’ I got the job and, over the last seventeen years, it has become a way of life – so this is a day of mixed feelings for me.”

By now, it was time to photograph Bob wearing his Jewel House Warden’s livery for the last time and then in his Pearly outfit. I could not avoid noticing a certain melancholy in Bob’s visage as he posed in his former working outfit, an emotion that was dispelled once he donned his new suit bespangled with buttons. Within moments, tourists were requesting pictures with Bob, Doreen & Larry. “There’s no retiring when you’re a Pearly King,” Larry whispered to Bob with a grin, offering good humoured reassurance as they posed for another photograph, “you don’t retire, you just die!”

Friday was Bob’s last day as Warden at the Jewel House

Bob relaxes with his Pearly pals

Bob with Doreen Golding, Pearly Queen of Bow Bells

Cap of Larry Golding, Pearly KIng of Bow Bells

Bob with Larry & Doreen Golding, Pearly King & Queen of Bow Bells

Larry, Doreen & Bob giving the Cockney salute outside the Tower

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

For I Will Consider My Cat Jeoffry

Bowing to popular demand, Paul Bommer has produced a new edition of his print inspired by Christopher Smart’s eulogy of his cat Jeoffry, coinciding with Paul’s return to Spitalfields from Norfolk bringing an exhibition of prints to the Townhouse Window in Fournier St. And today I republish my story of Christopher Smart & Jeoffry in Old St, telling the tale behind this celebrated verse.

Whenever I walk along Old St, I always think of the brilliant eighteenth century poet Christopher Smart who once resided here in St Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics, with only his cat Jeoffry for solace, on the spot where the Co-operative and Argos are today. So when artist Paul Bommer asked me to suggest a subject for an illustrated print, I had no hesitation in proposing Christopher Smart’s eulogy to his cat Jeoffry, the best description of the character of a cat that I know. And, to my amazement and delight, Paul has illustrated all eighty-nine lines, each one with an apposite feline image.

In an age when only aristocrats with private incomes were able to exist as poets, Christopher Smart was a superlative talent with small means who struggled to make his path through the world and his emotional behaviour became increasingly volatile as a result. He fell into debt whilst a student at Cambridge and, even though his literary talent was acknowledged with awards and scholarships, his delight in high jinks and theatrical performances did not find favour with the University. Once he married Anna Maria Canaan, Smart was unable to remain at Cambridge and came to London, seeking to make ends meet in the precarious realm of Grub St. His prolific literary career turned to pamphleteering and satire, publishing hundreds of works in a desperate attempt to keep his wife and two little daughters, Marianne and Elizabeth Ann.

Eventually, he signed a contract to write a weekly magazine, The Universal Visitor, and the strain of producing this caused Smart to have a fit, sometimes ascribed as the origin of his madness. Yet there are divergent opinions as to whether he was mad at all, or whether his consignment was in some way political on the part of John Newbery, the man who was both Smart’s publisher and father-in-law. However, Smart made a religious conversion at this time, and there is an account of him approaching strangers in St James’ Park and inviting them to pray with him.

In Smart’s day, Old St was the edge of the built up city with market gardens and smallholdings beyond. The maps of St Luke’s Hospital show gardens behind and it was possible that like John Clare in the Northamptonshire Lunatic Asylum, Smart was simply left alone to tend the garden and get on with his writing. Consigned at first on 6th May 1757 as a “curable” patient, Smart was designated “incurable” whilst there and subsequently transferred to Mr Potter’s asylum in Bethnal Green as a cheaper option – at a location known to this day as “Barmy Park.” Meanwhile, his wife Anna Maria took their two daughters to Ireland and he never saw them again. In 1763, Smart was released through intervention of friends and lived eight another years, imprisoned for debt in King’s Bench Walk Prison in April 1770, he died there in May 1771.

“For I Will Consider My Cat Jeoffry” was never printed in Smart’s day, it was first published in 1939 after being discovered in manuscript amongst Smart’s papers, and subsequently W.H. Auden gave a copy to Benjamin Britten who wrote a famous setting as part of a choral work entitled “Rejoice in the Lamb” in 1942.

The irony is that the “madness” of Christopher Smart, which was his unravelling as a writer in his own time, signified the creation of him as a poet who spoke beyond his age. Smart is sometimes idenitified as one of the Augustan poets, notable for their formality of style and content, but the idiosyncratic language, fresh observation and fluid form of “For I Will Consider My Cat Jeoffry” break through the poetic convention of his period and allow the poem to speak across the centuries.

It is the tender observation present in these lines that touches me most, speaking of the fascination of a cat as a source of joy for one with nothing else in the world. In fact, Smart was often known as Kit or Kitty and I wonder if he saw an image of himself in Jeoffry and it liberated him from the tyranny of his circumstance. Simply by following his nature, Jeoffry becomes holy in Christopher Smart’s eyes, exemplifying the the wonder of all creation.

It was a triumphant observation for a man who was losing his life, yet it is all the more remarkable that it is solely through this playful masterpiece he is remembered today. He did not know that – at the moment of disintegration – his words were gaining immortality thanks to the presence of his cat Jeoffry. And this is why, whenever I walk along Old St with my face turned to the wind, I cannot help thinking of poor Christopher Smart.

Christopher Smart (1722-71)

Paul Bommer at St Luke’s, Old St.

The St Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics in Old St where Christopher Smart lived with his cat Jeoffry on a site now occupied by Argos and The Co-operative.

St Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics, Old St, in the nineteenth century.

Paul Bommer in the rose garden on the site of the former St Luke’s Hospital garden where Christopher Smart’s cat Jeoffry once roamed.

Paul Bommer’s print of Christopher Smart’s “For I will consider my cat Jeoffry.”

The Gentle Author’s cat Mr Pussy.

Copies of Paul Bommer’s new edition of Christopher Smart’s “For I will consider my cat Jeoffry” are available from the Spitalfields Life online shop.

Artwork copyright © Paul Bommer

Archive image from Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about