So Long, Mr Pussy

Mr Pussy 2001-2017

The other night, I woke in the small hours to the sound of a clock ticking and I walked through the dark rooms, mystified at the origin of this strange rhythmic beat in my house which has no mechanical timepieces. Then I returned to my bedroom and I discovered the source of the sound. In the manner of Captain Hook’s crocodile, the ticking was coming from inside my old cat Mr Pussy. I squatted down to touch him where he lay, stretched out in the wing chair, and I discovered to my alarm that his breathing had become a harsh muscular spasm convulsing his body.

Next morning, his breathing softened and he lay stretched out in weary endurance upon the wooden floor. Occasionally, he would stand and change position. He would not eat but, if I held a dish out to him, he could lap up water and swallow it. I stroked his head and he purred at my touch. Overcoming his lethargy, Mr Pussy walked to the window and took up his usual position, peering over the sill with pleasure at the wonder of sunlight upon leaves and the infinite minutiae of the living world.

It is more than six months since I have had an unbroken night’s sleep. Consistently Mr Pussy has woken me with his cries and overcome my resistance to wake and pay attention to him. As I arose, he would run from the bedroom, expecting me to follow, and either make his way to the kitchen or the front door. If it was the front door, I opened it even though he had his own cat door. Secure in the knowledge of my oversight, Mr Pussy would take a wary look outside and, if all was clear, he would wander off into the night. If he led me to the kitchen, he would sit by his dish and look up at me in overstated expectancy, even if there was food already upon his plate. Often, after I fed him, he would follow me back to the bedroom and cry again. This charade might be repeated several times through the night until I could find some novelty to appease him – by running water in the bath for him to lap up or discovering some forgotten chicken liver in the fridge.

Sometimes, Mr Pussy would just sit and cry at me. I could not understand his night terrors. How I wished for words in those moments. As a last resort, I took him to bed and cuddled him against my chest – as I had done when he was a small kitten – until he quietened.

Only once, I lost patience and shut the door to him, foolishly hoping that he could be silenced and I might get some sleep. His cries were vigorous enough to wake the entire street and, unwilling to risk complaints from my neighbours, I had no choice but to let him in again and resume our pitiful nocturnal ritual. In the morning, Mr Pussy would be peaceful and climb onto the bed to slumber. When I could, I slept late or took afternoon naps to recover. I was disappointed at myself that I could find no comfortable resolution, though I feared that a resolution would come of its own accord before too long. Mr Pussy had been afflicted with anaemia for a while, although the precise cause of this was never diagnosed and medications proved to be of limited effect against the inevitable.

Denying he might not recover, I still had hope when I took him to the veterinary surgery that there might be a way to restore his breathing. Meanwhile, peering from the taxi window, Mr Pussy was overwhelmed with surprise at the vast spectacle of the city and its streets, a new vision of another universe revealed beyond his domestic existence.

Nothing could be done that would extend Mr Pussy’s life, improve his breathing or restore his being, and I gave my consent to end his days. The vet fitted a tube to Mr Pussy’s leg and I sat on a chair next to the table where he stood to face his death while still gasping for life. His body was strong but his internal organs had failed him. Mr Pussy looked at me and I stroked his head as the vet administered a lethal dose of anaesthetic. I expected Mr Pussy to grow weary and fade out, but he crumpled immediately like a punctured balloon and the life was gone from him in an instant. His furry carcass was dead at once upon the table.

Mr Pussy possessed a strength of spirit and presence of mind that never ceased to fascinate and inspire me. Equally, he spent every day of his life among humans and he studied them with his quick intelligence as a source of never-ending interest. It was a relationship of mutual curiosity.

How grateful I am that his deep golden eyes were undimmed until the end and the extraordinary softness of his black fur was never corrupted. Whenever I picked him up, I was always astonished by the miracle of his small lithe body, quivering alive. How I loved the honey-sweet fragrance of the short fur between his ears.

For sixteen years, through the travails of my life, my cat Mr Pussy was with me. When my mother died, he consoled me. When I sold my childhood home and left, he travelled with me. When I walked all night through the streets of London on Christmas Eve, he waited for my return. When I broke my arm and lay alone in bed shivering, he was beside me. Writing is a solitary activity but, as I sat working each day, through the long hours and the years, he was always at my side as a calm and patient presence. I could never be lonely while he was here.

I realise now that he was always in the periphery of my vision and, even now that he is gone, he remains in the margin of my sight. It will be a while before he fades from my familiar expectation. I hear sounds in the house and attribute them to him without thinking. Thanks to the reflex of my unconscious recognition, any deep shadow or dark shape I spy transforms itself into him. Even now, I expect him to enter the room or to come upon him in any of his familiar spots. Yet he is not here any more and his favourite places are vacant. Returning last night, I could not rest at home and left to wander the streets for an hour instead to calm my troubled spirits. The house had never felt so empty.

I cast my mind back through time. Exactly half a century has passed since I acquired my first cat, a grey female tabby whom I named simply ‘Pussy.’ For my birthday, I was given the right to choose a kitten for myself from a litter that were born in the next street, in recognition of my progress in life, shortly before I commenced preparatory school.

How curious, fifty years later, to be confronted with my former self, a lonely child delighted by a tiny kitten, and to appreciate – for the first time – my mother’s motives in giving me a cat. Although she never expressed it overtly to me, I realise now that she saw a pet as the solution to ameliorate the loneliness of her only child. She encouraged me to read books and to write stories of my own too.

All these summers later, I sit here now alone after the death of my old cat and I am grateful for this recognition of her insight and kindness, newly granted. Writing has filled my life and I understand how this moment today is the outcome of that earlier moment a lifetime ago, when the world was a different place and I was a different person too. It was the first moment when a cat came along to guide me, leading me on the long journey, through all that time to the point of writing these words.

Mr Pussy was a fine creature and he lived a fine life.

Mr Pussy was my cat.

How I miss him now I mourn him.

READ ABOUT THE LIFE & TIMES OF MR PUSSY

James McNeill Whistler In The East End

Writing my new book EAST END VERNACULAR, Artists who painted London’s East End streets in the 20th century to be published by Spitalfields Life Books in October, has brought me to a new appreciation of the work of James McNeill Whistler.

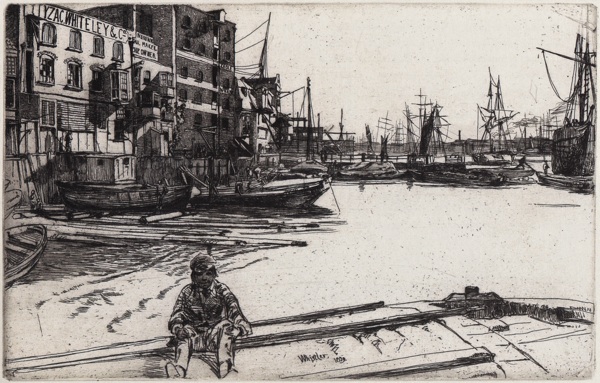

In the mid-nineteenth century, Whistler was the first artist to appreciate the utilitarian environment of the East End on its own terms, seeing the beauty in it and recognising the intimate relationship of the working people to the urban landscape they had constructed. Many other artists became fascinated by Whistler’s vision and were inspired to follow in his footsteps, some embracing his medium of etching, like Joseph Pennell, while others like Frank Brangwyn and C R W Nevinson – and more recently, John Minton, Roland Collins and Jock McFadyen – were attracted by the spectacle of the docks and the life of the river.

Click here to preorder your copy of EAST END VERNACULAR

William Jones, Limeburner, Wapping High St

American-born artist, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, was only twenty-five when he arrived in London from Paris in the summer of 1859 and, rejecting the opportunity of staying with his half-sister in Sloane St, he took up lodgings in Wapping instead. Influenced by Charles Baudelaire to pursue subjects from modern life and seek beauty among the working people of the teeming city, Whistler lived among the longshoremen, dockers, watermen and lightermen who inhabited the riverside, frequenting the pubs where they ate and drank.

The revelatory etchings that he created at this time, capturing an entire lost world of ramshackle wooden wharfs, jetties, warehouses, docks and yards. Rowing back and forth, the young artist spent weeks in August and September of 1859 upon the Thames capturing the minutiae of the riverside scene within expansive compositions, often featuring distinctive portraits of the men who worked there in the foreground.

The print of the Limeburner’s yard above frames a deep perspective looking from Wapping High St to the Thames, through a sequence of sheds and lean-tos with a light-filled yard between. A man in a cap and waistcoat with lapels stands in the pool of sunshine beside a large sieve while another figure sits in shadow beyond, outlined by the light upon the river. Such an intriguing combination of characters within an authentically-rendered dramatic environment evokes the writing of Charles Dickens, Whistler’s contemporary who shared an equal fascination with this riverside world east of the Tower.

Whistler was to make London his home, living for many years beside the Thames in Chelsea, and the river proved to be an enduring source of inspiration throughout a long career of aesthetic experimentation in painting and print-making. Yet these copper-plate etchings executed during his first months in the city remain my favourites among all his works. Each time I have returned to them over the years, they startle me with their clarity of vision, breathtaking quality of line and keen attention to modest detail.

Limehouse and The Grapes – the curved river frontage can be recognised today

The Pool of London

Eagle Wharf, Wapping

Billingsgate Market

Longshore Men

Thames Police, Wapping

Black Lion Wharf, Wapping

Looking towards Wapping from the Angel Inn, Bermondsey

You may also like to read about

Dickens in Shadwell & Limehouse

Madge Darby, Historian of Wapping

Views from a Dinghy by John Claridge

Click here to preorder a copy of EAST END VERNACULAR for £25

At Empress Coaches

Peter Stanton

One of the corners of the East End that intrigues me most is at the boundary of Bethnal Green and Hackney, where a narrow path bordered by crumbling old brick walls leads up from the Hackney Rd to the junction of Mare St and the Regent’s canal. Cutting through at an angle to the grid of streets, it has the air of a field track that was there before the roads and the railway. Looming overhead against the skyline is a tall ruinous structure with the square proportions of a medieval castle, London’s last unreconstructed bomb site, left to decay since an incendiary hit in World War II. Beyond this, you pass under the glistening railway arches to arrive at the canal where, to your left, a vista opens up with majestic gasometers reaching up the sky and a quaint old building with bay-fronted windows entirely overgrown with ivy, cowering beneath. This is the headquarters of Empress Coaches.

Here I received a generous welcome from Peter Stanton, third generation of the Stanton family at the coach yard and still operating from the extravagantly derelict premises purchased by his grandfather.

Edward Thomas Stanton was an enterprising bus driver who bought his bus in 1923 and created a fleet operating from a yard in Shrubland Rd, London Fields, whence he initiated several familiar bus routes – including the No 8 pictured above on the office wall – journeys that became part of the perception of the city for generations of Londoners. In 1927, he bought the property here in Corbridge Crescent but when the buses were nationalised in 1933, he made £35,000 from the sale of the fleet, permitting him to retire and hand over to his son Edward George Stanton, changing the business from buses to coaches at the same time. “It was a bloody fortune then!” declared Peter, his grandson still presiding with jocularity over the vestiges of this empire today. Outside the fleet of coaches in their immaculate cream paintwork, adorned with understated traditional signwriting sat dignified and perfect as swans amidst the oily filth of the garage, ready to glide out over the cobbles and onto the East End streets.“A coach yard within two miles of the City of London, it will never happen again,” declared Peter in wonder at the arcane beauty of his inheritance.

“My father came here at sixteen with his sister Ivy who did all the accounts,” he explained, sitting proudly among framed black and white photographs that trace the evolving design of coaches through the last century. At first, the bodies of the vehicles were removed in the winter to convert to flat trucks out of season and these early examples resemble extended horsedrawn coaches but, as the century wore on, heroically streamlined vehicles took over. And the story of Empress Coaches itself became interwoven with the history of the twentieth century when they were requisitioned during World War II to drive personnel around airfields in Norfolk, while the staff that remained in London took refuge in the repair pit in the coach yard as a bomb shelter during the blitz.

“My father didn’t encourage me to come into the business,” admitted Peter, who joined in 1960, “But after being brought up around coaches and coming up here every Saturday morning with your dad, it gets into your blood and I could think of nothing else but going into it. I started off at the bottom, I was crawling under the coaches greasing them up. I was a mechanic for twenty-two years but then me and my brother Trevor bought out the company from the rest of the family, and the two of us took it over.”

“In those days, people didn’t go on holidays, they had a day out to the sea on a coach. And they had what they called “beanos,” pub and work excursions going to Margate or Southend and stopping at a pub on the way back and arriving back around midnight. Those pubs used to lose their local trade because people didn’t want to go into a bar filled with a lot of drunken East Enders. They were very rowdy and the girls were as bad as the boys.” revealed Peter, able to take amusement now at this safe distance and pulling a face to indicate that there is little he has not seen on the buses. “Put it like this, I used to say that when you took a coachload of girls out on a beano and their boyfriends and husbands came to pick them up at one o’clock – if they knew what I knew these girls had been up to they wouldn’t be so welcoming. In other words, they were not so innocent in those days as people thought they were. But the police were the worst, they went bloody barmy and they did things they would nick anybody else for doing!”

“When I first started there were six beanos every Saturday in the Summer but in the whole of the last year we only did two.” he admitted with a private twinge of disappointment. As the beanos decreased in the sixties, Empress Coaches were called upon by the military for troop movements. “We used to do the Trooping of the Colour, we drove the troops from Caterham Barracks with a police escort. It was the time of the IRA and they had to check all the bins along the way and have a guy with a jammer sitting in the front of the bus, so if there was a remote-controlled bomb it wouldn’t go off. They told us, ‘Whatever you do, drive on. Even if you hit someone.’ There’d be twenty of our coaches full of soldiers plus an escort.”

These are now the twilight years at Empress Coaches, after the family sold the business and are simply employed to keep it ticking over, which explains why little maintenance is undertaken. Yet the textures of more than eighty years of use recall the presence of all those who passed through and imbue the place with a rare charmed atmosphere. I was not the first to recognise the appeal of its patina, as I discovered when Peter reeled off the list of film crews that had been there, most notably “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy” who wallpapered his office with the gold wallpaper you see in the top picture. “We’ve had Michael Caine here,” he boasted, “Gary Oldman, Ray Winstone and Dennis Waterman too.”

“After I spent fifty-two years of my life here, I’ve got be here.” Peter assured to me, biting into a sandwich and chewing thoughfully,“It’s more than likely this place will be redeveloped before too long and that will be the end of it, but in the meantime – I’m just trying to keep this show on the road!”

Edward Thomas Stanton, the enterprising bus driver who invented the number eight bus route.

Edward George Stanton in his leather bus driver’s coat.

Brothers Peter and Trevor Stanton.

Mark Stanton, Trevor’s son.

Jason Stanton, Peter’s son.

Between the coaches.

A forgotten corner of the yard.

Empress Coaches, the office entrance.

Corbridge Crescent, with the canal to the right.

London’s last unreconstructed bomb site.

You may also like to read about two nearby industries

Summer At Arnold Circus

At this time of year, the canopy of trees over-arching Arnold Circus is an awe inspiring sight to behold, as if a forest clearing had been magically transported and placed at the centre of a maze of city streets. From within the tiny park you see the towering red brick mansion blocks framed by trees, imparting an atmosphere of lyrical romance entirely in tune with the Arts & Crafts ethos of Britain’s first Council Estate.

Yet, if you wander further within the Estate, you come upon satellite gardens contrived by the residents using old baths, canes and twigs as a means to create temporary vegetable plots among the yards between the buildings. The idiosyncratic forms of these curious contraptions hung with glinting things offer a sympathetic complement to the regularity of the architecture and it makes your heart leap to see cherished home grown vegetables nurtured so tenderly in unexpected circumstances.

You might also like to take a look at

At David Kira Ltd

To anyone that knows Spitalfields, David Kira Ltd is a familiar landmark at 1 Fournier St next to The Ten Bells. Here, at the premises of the market’s foremost banana merchant – even though the business left more than a quarter of a century ago – the name of David Kira is still in place upon the fascia to commemorate the family endeavour which operated on this site for over half a century.

By a fluke of history, the shop that trades here now has retained the interior with minimum intervention, which meant that when David’s son Stuart Kira returned recently he found it had not been repainted since he left in 1991 and his former office, where he worked for almost thirty years – and even his old chair – was still there, existing today as part of a showroom for shoes and workwear.

This is a story of bananas and it began with Sam Kira in Southend, a Jewish immigrant from Poland who became naturalized in 1929 and started a company called “El Dorado Bananas.” Ten years later, his son opened up in Fournier St as a wholesaler, taking a lease from Lady Fox but having to leave the business almost at once when the war came, bringing conscription and wiping out the banana trade. Yet after the war, he built up the name of David Kira, creating a reputation that is still remembered fondly in Spitalfields and, since the shop remains, it feels as if the banana merchants only just left.

“When I first came to the market as a child of seven, we lived in Stoke Newington and took the 647 trolley bus to Bishopsgate and walked down Brushfield St. Every opportunity, I came down to enjoy the action and the atmosphere, and the biggest thrill was getting up early in the morning – I always remember being sent round to the Market Cafe to get mugs of tea for all the staff. When I joined my father David in 1962, aged sixteen, my grandfather Sam had died many years earlier. There was me and my father, John Neil (who had been with my father his entire working life), Ted Witt our cashier, two porters, Alf Lee and Billy Alloway (known as Billy the thief) and we had an empty boy. Our customers were High St greengrocers and market fruit traders, and we prided ourselves on only selling the best quality produce. Perhaps this was why we had a lot of customers. It was hard work and long working hours, getting up at half past four every morning to be at the market by five thirty. I used to sleep for a couple of hours in the afternoon when I got home, until about six, then I’d get up and return to bed at eleven until four thirty – I did that six days a week.

We received our shipments direct from Jamaica through the London Docks – bananas in their green state on long stalks – they arrived packed in straw on a lorry and it was very important that they be unloaded as soon as they arrived, whatever time of day or night the ship docked, because the enemy of the banana is the cold. They were passed by hand through a hatch in the floor to the ripening rooms downstairs – it took five days from arrival until they were saleable. Since the bananas came from the tropics, it was not so much the heat you had to recreate as the humidity. We had a single gas flame in the corner of each ripening room, the green bananas hung close together on hooks from the ceiling and, when the flame was turned down, a little ethylene gas was released before the door was sealed. Once they were ripened, they had to be boxed. You stood with a stalk of bananas held between your legs and struck off each bunch with a knife, placing it in a special box, three foot by one foot – a twenty-eight pound banana box.

During the sixties, dates were only sold at Christmas but in the seventies when the Bangladeshi people arrived, we started getting requests for dates during Ramadan. I contacted one of the dates suppliers and I asked him to send me thirty cases, and they were sold to Bengali greengrocers in Brick Lane before they even touched the floor. Subsequently, we sold as many dates as we could get hold of, more even than at Christmas. During this period, we also saw the decline of the High St greengrocers due to the supermarkets, however we found we were able to compensate for the loss of trade by fulfilling the requirements of the Asian community.

Eventually, they started importing pre-boxed bananas in the eighties, so our working practices changed and the banana ripening rooms became obsolete. My late father would be turning in his grave if he knew that bananas are now placed in cold storage, which means they will quickly turn black once they get home.

In 1991, when the market moved, we were offered a place in the new market hall but trading hours became a free-for-all and, although we started opening at three am, we were among the last to open. By then I was married and had children, and without the help of my father and John Neil who had both retired, I found it very difficult to cope. It was detrimental to my health – so, after a year, I sold the company as a going concern. I didn’t know what I wanted to do, but by chance I bumped into a colleague who worked in insurance and he introduced me to his manager. I realised in that type of business I could continue to be self-employed, so I trained and qualified and I have done that for the past twenty years. When I think back to the market, I only got two weeks a year holiday and I felt guilty even to put that pressure on my father and John Neil when I was away.”

Proud of his father’s achievement as a banana merchant, Stuart delighted to tell me of Ethel, the rat-catching cat – named after the ethylene gas – who loved to sleep in the warmth of the banana ripening rooms and of Billy Alloway’s tip of sixpence that he nailed to the wall in derision, which stayed there as his memorial even after he died. Stuart cherishes his memory of his time in the market, recognising it as a world with a culture of its own as much as it was a place of commerce. Today, the banana trade has gone from Spitalfields where once it was a way of life, now only the name of David Kira – heroic banana merchant – survives to remind us.

Sam Kira (far right) dealing in bananas in London and Southend.

Sam Kira’s naturalization papers.

David Kira at the Spitalfields Fruit Exchange – he is centre right in the fifth row, wearing glasses and speaking with his colleague.

The banana trade ceased during World War II.

The banana trade ceased during World War II.

David Kira as a young banana merchant.

David Kira (left) with his son Stuart and business partner John Neil.

David Kira and staff.

Stuart Kira stands in the doorway of his former office of twenty years, where his father and grandfather traded for over fifty years, now part of a hairdressing salon.

David Kira Ltd, 1991

First and last pictures copyright © Mark Jackson & Huw Davies

You may also like to read about

Jimmy Huddart, Spitalfields Market Porter

Peter Thomas, Fruit & Vegetable Supplier

Ivor Robins, Fruit & Vegetable Purveyor

John Olney, Donovan Brothers Ltd

Jim Heppel, New Spitalfields Market

Blackie, the Last Spitalfields Market Cat

and take a look at these galleries of pictures

Hopping Photography

This selection of favourite Hop Pickers’ photographs is from the archive of Tower Hamlets Community Housing. Traditionally, this was the time when East Enders headed down to the Hop Farms, embracing the opportunity of a breath of country air and earning a few bob too.

Bill Brownlow, Margie Brownlow, Terry Brownlow & Kate Milchard, with Keith Brownlow & Kevin Locke in front, at Guinness’ Northland’s Farm at Bodiam, Sussex, in 1958. Guinness bought land at Bodiam in 1905 and eight hundred acres were devoted to hop growing at its peak.

Julie Mason, Ted Hart, Edward Hart & friends at Hoathleys Farm, Hook Green, near Lamberhurst, Kent

Lou Osbourn, Derek Protheroe & Kate Day at Goudhurst Farm

Margie Brownlow & Charlie Brownlow with Keith Brownlow, Kate Milchard & Terry Brownlow in front at Guinness’ Northland’s Farm at Bodiam, Sussex, in 1950

Mr & Mrs Gallagher with Kitty Adams & Jackie Gallagher from Westport St, Stepney, in the hop gardens at Pembles Farm, Five Oak Green, Kent in 1959

Jackie Harrop, Joan Day & George Rogers at Whitbread’s Farm, Beltring, Kent in 1949

Mag Day (on the left at the back) in the hop gardens with others at Highwood’s Farm, Collier St, in 1938

Pop Harrop at Whitbread’s Farm, Beltring, Kent in 1949

Sarah Watt, Mrs Hopkins, Steven Allen, Ann Allen, Tom, Albert Allen & Sally Watt in the hop gardens at Jack Thompsett’s Den Farm, Collier St, Kent in 1943

Harry Watt, Tom Shuffle, Mary Shuffle, Sally Watt, Julie Callagher, Ada Watt & Sarah Watt in the hop gardens at Jack Thompsett’s Den Farm, Collier St, Kent in the fifties

Harry Watt, Sally Watt, Sarah Watt holding Terry Ellames in the hop gardens at Jack Thompsett’s Den Farm, Collier St, Kent in 1957

Harry Ayres, a pole puller, in the hop gardens at Diamond Place Farm, Nettlestead, Kent

Emmie Rist, Theresa Webber, Kit Webber & Eileen Ayres in the hop gardens at Diamond Place Farm, Nettlestead, Kent

Kit Webber with her Aunt Mary, her Dad Sam Webber and her Mum, Emmie Ris,t in the hop gardens at Diamond Place Farm, Nettlestead, Kent

Harry Ayres with his wife Kit Webber in the hop gardens at Diamond Place Farm, Nettlestead, Kent.

Richard Pyburn, Mag Day, Patty Seach and Kitty Gray from Kirks Place, Limehouse, in the hop gardens at Highwoods Farm, Collier St, Kent

The Gorst and Webber families at Jack Thompsett’s Farm, Fowle Hall, Kent in the forties

Kitty Waters with sons Terry & John outside the huts at Pembles Farm, Five Oak Green, Kent in 1952

Mr & Mrs Gallagher from Westport St, Stepney, with their grandchildren in the hop gardens at Pembles Farm, Five Oak Green, Kent in 1958

Sybil Ogden, Doris Cossey, Danny Tyrrell & Sally Hawes near Yalding, Kent

John Doree, Alice Thomas, Celia Doree & Mavis Doree in the hop gardens near Cranbrook, Kent

Bill Thomas & his wife Annie, in the hop gardens near Cranbrook, Kent

The Castleman Family from Poplar hop picking in the twenties

Terry & Margie Brownlow at Guinness’ Northland’s Farm at Bodiam in Sussex in 1949

Alfie Raines, Johnny Raines, Charlie Cushway, Les Benjamin & Tommy Webber in the Hop Gardens at Jack Thompsett’s Farm at Fowl Hall near Paddock Wood in Kent

Lal Outram, Wag Outram & Mary Day on the common at Jack Thompsett’s Farm at Fowl Hall near Paddock Wood in Kent in 1955

Taken in September 1958 at Moat Farm, Five Oak Green, Kent. Sitting on the bin is Miss Whitby with Patrick Mahoney, young John Mahoney and Sheila Tarling (now Mahoney) – Sheila & Patrick were picking to save up for their engagement party in October

Maryann Lowry’s Nan, Maggie ,on the left with her Great-Grandmother, Maryann, in the check shirt in the hop gardens, c.1910

Having a rest in hop gardens at Whitbread’s Farm, Beltring, Kent in 1966. In the back row are Mary Brownlow, Sean Locke, Linda Locke, Kate Milchard, Chris Locke & Margie Brownlow with Kevin Locke and Terry Locke in front.

Margie Brownlow & her Mum Kate Milchard at Whitbreads Farm in Beltring, Kent in 1967. These huts were two stories high. The children playing outside are – Timmy Kaylor, Chrissy Locke, Terry Locke, Sean Locke, Linda Locke & Kevin Locke.

Chris Locke, Sally Brownlow, Linda Brownlow, Kate Milchard, Margie Brownlow, Terry Locke & Mary Brownlow at Whitbread’s Farm, Beltring, Kent in 1962

Johnno Mahoney, Superintendant of the Caretakers on the Bancroft Estate in Stepney, driving the “Mahoney Special” at Five Oak Green in 1947

The Clarkson family in the hop gardens in Staplehurst. Gladys Clarkson , Edith Clarkson, William Clarkson, Rose Clarkson & Henry Norris.

John Moore, Ross, Janet Ambler, Maureen Irish & Dennis Mortimer in 1950 at Luck’s Farm, East Peckham, Kent

Kate Fairclough, Mrs Callaghan, Mary Fairclough & Iris Fairclough at Moat Farm, Five Oak Green, Kent in 1972

A gang of Hoppers from Wapping outside the brick huts at Stilstead Farm, Tonbridge, Kent with Jim Tuck & John James in the back. In the middle row the first person on the left is unknown, but the others are Rose Tuck, holding Terry Tuck, Rose Tuck, Danny Tuck & Nell Jenkins. In the front are Alan Jenkins, Brian Tuck, Pat Tuck, Jean Tuck, Terry Taylor & Brian Taylor.

Nanny Barnes, Harriet Hefflin, “Minie” Mahoney & Patsy Mahoney at Ploggs Hall Farm

In the Hop Gardens at Jack Thompsett’s Farm at Fowl Hall, near Paddock Wood in Kent in the late forties. Alfie Raines, Edie Cooper, Margie Gorst & Lizzie Raines

The Day family from Kirks Place, Limehouse, at Highwoods Farm in Collier St, Kent in the fifties

Annie Smith, Bill Daniels, Pearl Brown & Nell Daniels waiting for the measurer in the Hop Garden at Hoathley’s Farm, Hook Green, Kent

On the common outside the huts at at Hoathley’s Farm, Hook Green, Kent – you can see the oasthouses in the distance. Rita Daniels, Colleen Brown, Maureen Brown, Marie Brown, Billy Daniels, Gerald Brown & Teddy Hart , with Sylvie Mason & Pearlie Brown standing.

The Outram family from Arbour Sq outside their huts at Hubbles Farm, Hunton, Kent. Unusually these were detached huts but, like all the others, they made of corrugated tin and all had one small window – simply basic rooms, roughly eleven feet square

Janis Randall being held by her mother Joyce Lee andalongside her is her father, Alfred Lee in a hop garden, near Faversham in September 1950

David & Vivian Lee sitting on a log on the common outside Nissen huts used to house hop pickers

Gerald Brown, Billy Daniels & Dennis Woodham in the hop gardens at Gatehouse Farm near Brenchley, Kent, in the fifties

Nelly Jones from St Paul’s Way with Eileen Mahoney, and in the background is Eileen’s mum, “Minie” Mahoney. Taken in the fifties in the Hop Gardens at Ploggs Hall Farm, between Paddock Wood and Five Oak Green.

At Jack Thompsett’s Farm at Fowl Hall, near Paddock Wood in Kent

Ploggs Hall Farm Ladies Football Team. Back Row – Fred Archer, Lil Callaghan, Harriet Jones, Unknown, Unknown, Nanny Barnes, Liz Weeks, Harriet Hefflin, Johnno Mahoney. Front Row – Doris Hurst Eileen Mahoney & Nellie Jones

John Moore, Ross, Janet Ambler, Maureen Irish & Dennis Mortimer in 1950 at Luck’s Farm, East Peckham, Kent

The Outram and Pyburn families outside a Kent pub in 1957, showing clockwise Kitty Tyrrell, Mary Pyburn, Charlie Protheroe, Rene Protheroe, Wag Outram, Derek Protheroe in the pram, Annie Lazel, Tom Pyburn, Bill Dignum & Nancy Wright.

Sally Watt’s Hop Picker’s account book from Jack Thompsett’s Den Farm, Collier St, Kent in the fifties

You may also like to take a look at

At William Gee Ltd

Speaking as a lifelong connoisseur of quality haberdashery, let me say that if you are in need of a button or a reel of thread, there is no finer place to go than William Gee Ltd at 520 Kingsland Rd. For the haberdashery lover, even the windows at William Gee set the pulse racing with their ingenious displays of words contrived from zips – yet it was my privilege recently to explore behind the scenes at this glamorous theatre of smallwares, trimmings, threads, buttons and zippers, visiting the mysterious warren of storerooms at the rear of the shop, where I met the self-respecting guardians of this beloved Dalston institution that styles itself as “trimmings for all trades.”

My guide was Jeffrey Graham, maestro of the proud company boasting London’s largest selection of zip fasteners. He led me up an old brown lino-covered staircase between walls panelled in wood-effect formica to the locked, dusty upper room lined with happy photos of works’ outings and jamborees of long ago. Here Jeffrey brought the title deed to the property dating from the sixteenth century when this was Henry VIII’s land – Henry was the king that the Kingsland Rd refers to – and he had stables here for hunting when there was still forest, recalled today only in the name of Forest Rd. Then, once we had established this greater chronological perspective, Jeffrey brought out the tiny sepia photograph of William Goldstein that illustrates where the haberdashery business began.

“William Goldstein started in 1906 with two pounds in the kitty selling buttons and trimmings, and he changed the company name to William Gee. This was across the road where Albert’s Cafe is now, but after several years he needed larger premises and moved into the current building. He had two sons, Alfred & Sidney, and I knew both of them. Alfred died in 1970 and Sidney worked until he was eighty-five, and died four or five years ago. They grew the business and made it one of the largest of its type in the country, at a time when there was a large textile industry in the East End – which was full of clothing factories until a few years ago.

In the middle of the last century, there were more than eighty people working here. I remember coming in as a child and there were twelve ladies who all had their own button-making machines for covering buttons and they’d all be sitting there jabbering away making buttons, and some had machines at home and even carried on making them there too. When I was twelve or fourteen, I did a holiday job helping out and going out on deliveries with the drivers, so I saw a lot of the places we delivered to. My impression was that everything was bustling, everyone was busy, no-one had any patience and everyone knew everyone.

My father, David Graham, had a similar business at 77 Commercial St. He served all the factories in the little streets around Spitalfields and my grandfather had a haberdashery shop before him, on Brick Lane, M.Courts – it was still there in name until very recently. In the early sixties, the two businesses merged and my father became managing director of William Gee and we were supplying manufacturing companies that made uniforms and corporatewear, brideswear companies, hospitals, sportswear companies, hatters in Luton, – anyone really.We were doing a wholesale business in bulk that was very competitive.

The heyday was in the sixties through into the eighties, before manufacturers began to have their clothes made by cheaper labour in Eastern Europe, North Africa, or the Far East where much of the clothing is made today. It closed many factories and suppliers, they could not compete. It was no accident that people talk about “sweatshops,” because there wasn’t legislation to control how they should be organised then, but after legislation was enforced employers could not compete with overseas competitors.

It became a thing that you were delivering to shippers rather than factories, and then the types of customers became smaller and more varied – from engineers and printers, to film and theatre companies like the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Royal Opera, and lots of designers including, Gareth Pugh, Alexander McQueen Matthew Williamson, Vivienne Westwood, Caroline Charles and Old Town. What has come instead is a cottage industry, where individual designers are setting up and making a business out of it, and one of the largest sources of sales in recent years have been the colleges for fashion, textiles and art departments. But there are so many of them now that I wonder what will all the students do afterwards?”

Leaving this question to resolve itself we set out to visit the departments. First the button department which fills the shop next door, where buttonmaker, Janet Vanderpeer, presides over neat shelves stacked with rare ancient buttons from companies that closed years ago. Here I found her secreted behind a curtain in a cosy den, placidly making fabric-covered buttons at a press. Did she like it? A nod to the affirmative. How long had she been doing it? “A good while.” And without missing a beat she kept the buttons coming.

From here, we passed behind the shop to the three storey warehouse where the comprehensive supply of zip fasteners are kept and tended by their own designated keeper “You might think a zip is just zip,” said Jeffrey, rolling his eyes and gesturing to the lines of shelves. Then we stepped out into Forest Close whence the works’ coach parties departed in the nineteen fifties and crossed the road to the large warehouse where Janet’s brother David Vanderpeer, despatch manager, who joined the company thirty years ago at the age of sixteen, inhabits his own cosy den complete with microwave and ceramic leopard.

All fourteen staff at William Gee today have been there at least ten years and there is a sense of quiet mutual understanding which enables everything to run smoothly. Jeffrey told me a man will come in to say that his grandmother sent him here to buy buttons as a child and then ten minutes later another senior gentleman will come in to say the same thing. Yet in this appealingly utilitarian shop, that appears sublimely unaffected by any modern intervention, whoever comes through the door to stand between the two long counters is met with respect and patience. Even the old lady who did a high kick to place her ankle on the counter, when I was there, in order to display the kind of elastic she required was met with unblinking courtesy. And when Jeffrey Graham informed me authoratively, “The styles of clothing may have changed but the basic components are the same whatever the fashion.” I could hardly disagree.

William Goldstein’s haberdashery shop in 1906, that became William Gee.

A leaving party for Ivy Brandon in the seventies, with David Graham on the far right and Sidney Gee on the far left.

Sidney Gee & David Graham celebrate the seventy-fifth anniversary in 1981

The warehouse round the corner in Forest Rd.

Princess Diana in a coat with lining supplied by William Gee, 1986.

Jeffrey Graham, Managing Director of William Gee.

Janet Vanderpeer, Buttonmaker.

David Vanderpeer, Despatch Manager.