The Gates Of Old London

Today I present these handsome Players Cigarette Cards from the Celebrated Gateways series published in 1907.

You may also like to take a look at these other sets of cigarette cards

At Clive Murphy’s Flat

As a follow-up to Saturday’s tribute to Clive Murphy who died last week at eighty-five, here is my account of his now legendary flat in Brick Lane.

Clive Murphy at his desk

Writer Clive Murphy lived in his two room flat above the Aladin Curry House on Brick Lane from 1974 and filled it with an ever-growing collection of books, papers and memorabilia. Once I heard he was going to tidy up, I realised I must record Clive’s glorious disarray lest his environment lose any of its charisma in the process of getting organised.

When Clive saw the card in the window and rented his flat, it was above a draper’s, but that went long ago as the Bengali shops and curry houses filled the street. Then, in more recent years, the nightlife arrived, with clubbers and party animals coming to throng Brick Lane at all hours. Yet, throughout this time, Clive lived quietly on the first floor, looking down upon the seething hordes of visitors and inhabiting a private world that was largely unchanged, save the accumulation of books and leaks in the ceiling.

Walking up the narrow staircase from the street, you came first to Clive’s kitchen looking back towards Hanbury St and Roa’s crane. At the front was a larger room looking onto Brick Lane which served as Clive’s bedroom and study, lined with fine furniture barely visible under the tide of paper and sitting beneath a water-stained ceiling that resembled a map of the world.

“I’ve had so may leaks and serious floods,” Clive recalled philosophically, “I have been sitting in the kitchen and water has come from the ceiling like from a tap. The landlord wanted to get me out because he could get seven times the rent, but when when the inspectors came round to assess the rent, I said, ‘Do you want to see my bathroom, it’s above the wardrobe?’ That brought my rent down.” And Clive raised his eyes to the tin bath on top of the wardrobe, chuckling in triumph.

Before he came to Spitalfields, Clive had already gained a reputation as a writer, with two novels and two volumes of oral history published. “When I first started writing, I’d write a short story and it’d be accepted, but then the pace slows down …” he confessed to me, casting his eyes over to the shelf dedicated to the volumes that comprise his life’s work and then gazing around at the piles of notebooks, files and packets of his books, mixed up with the contents of his library scattered higgedly-piggedly around the room.

“You see that suitcase,” he indicated, casually gesturing back to the tin bath which I now realised contained a battered case with a tag, “it has a novel in it.” I enquired about a stack of thirty old exercise books which caught my eye. “They are for the continuation of one of my novels, eventually I might read the whole lot and write a book” Clive assured me, turning to point out a selection of bibles on the shelf next to his bed. “My mother became a bit holy in old age, but that was because her friend seduced her into religion,” he informed me wearily, just in case I might assume they were his, “I think if people convert to Christianity in later life it’s a symptom they have lost their minds or need an emotional crutch to lean on.”

On the floor next to the bed was a wallpaper pattern book with newspaper cuttings pasted in it, the most recent of twenty-seven volumes that Clive had filled. “I collect all the things and people that interest me, either because they attract me or because I dislike them,” he explained, “I also keep all correspondence and note all phone calls.”

Visiting Clive’s flat was like entering his crowded mind, containing all the books he had read, all his own work and all the minutiae of life he had sought to preserve. It was the outcome of Clive’s infinite curiosity about life. “I used to walk all night and have lots of promiscuous encounters,” he confided to me, “I was an immigrant and I had to make friends. They say, ‘Don’t talk to strangers,’ but I think that’s very stupid advice because if I didn’t talk to strangers I’d have known nobody. I’m a very gregarious person, hence by talking to people at great length I got to know them.”

It was Friday afternoon and Clive was bracing himself for the approaching weekend and the ceaseless nocturnal crowds beneath his window. “It does keep you alert and alive and interested,” he admitted to me with characteristic good grace, “I don’t know anywhere else now and I have grown to love my little world. I like being in the hub of things.”

Clive never did tidy up, in the end he always had better things to do.

In Clive’s kitchen.

Note the wallpaper pattern books which Clive uses as scrap books for his press cuttings.

Clive at his desk overlooking Brick Lane.

“When the inspectors came round to assess the rent, I said, ‘Do you want to see my bathroom, it’s above the wardrobe?’ That brought my rent down.”

You may also like to read

At Sutton House

I love to visit dark old houses on bright summer days. There is something delicious about stepping from the heat of the day into the cool of the interior, almost as if the transition from one temperature to another was that of time travel, from the present into another era.

I wonder if this notion is a residue of my childhood, when my parents took me on summer trips to visit stately homes, so that now I associate these charismatically crumbling old piles of architecture with warm English afternoons.

Such were my feelings when visiting Sutton House, the oldest house in the East End, recently. It made me think of the country mansions of city burghers that once filled Spitalfields before the streets were laid out and the terraces built up.

Built between 1534-5 by Ralph Sadleir, an associate of Thomas Cromwell, Sutton House employed oak beams from the royal forest of Enfield given to Cromwell by Henry VIII. In 1550, Sadleir sold his house to John Machell who became Sheriff Of London, acquiring wealth as a City merchant. Overreaching himself in debt, the house was repossessed by Sir James Deane, a money-lender.

By 1627, it was in the ownership of Captain John Milward, a silk merchant and member of the East India Company, who furnished it with oriental carpets and commissioned elaborate strapwork murals upon the staircase that survive in fragments to this day.

Sarah Freeman leased the house in 1657 for a girls’ school which ran for nearly a century until it was divided into two dwellings in the mid-eighteenth century, Ivy House and Milford House. Only at the end of the nineteenth century were the two halves reunited when Canon Evelyn Gardner created St John’s Institute as a recreational club for ‘men of all classes.’ Within ten years the building was condemned as unsafe, but thanks to a public appeal which raised £3000 it was extensively renovated with additions in the Arts & Crafts style.

After the Institute left, a failed attempt was made to buy Sutton House for the nation before the National Trust stepped in to save it in 1938. For decades, rooms were let as offices to voluntary organisations until squatters occupied the house in the eighties. Then developers were prevented from converting it into luxury flats by a successful local campaign to Save Sutton House which eventually opened to the public in 1991.

Thus history passed through Sutton House like a whirlwind yet, despite all the changes, the atmosphere of past ages still lingers, especially in the shadowy panelled rooms that enfold the overwhelming mystery of numberless untold stories.

Tudor door and Georgian fanlight

Original transom window dating from the Tudor era

In the Linenfold Parlour

Looking downstairs from the Great Chamber

Looking from the Little Chamber into the Great Chamber

The Great Chamber

Cabinet in the Little Chamber

Tudor kitchen

Cellar stairs

Looking through the courtyard

Looking up from the courtyard

Known as the ‘Armada Window,’ this is the oldest window in the East End

Sutton House can be visited as part of a guided tour. Tickets go on sale every Friday for tours on the following Wednesday, Friday & Sunday.

You may also like to read about

Tea With David Bowie

I am delighted to publish this memoir by Cherry Gilchrist

Cherry in 1965

“It was 1965, and my schoolfriend Helen and I, aged sixteen, were spending a weekend in London. This was something we had to beg and plan for, getting our parents on side and making all sorts of promises as to what we would not do in regard to men, drink, and sleazy music clubs.

Our mothers only consented to this dangerous undertaking provided we stayed at the respectable YWCA girls’ hostel in Marylebone. Little did they know that even there we would have to fend off the amorous advances of African students who were keen to get to know English girls – they were staying the equivalent men’s hostel down the road. We made sure we kept our interaction to playing table tennis and talking urgently about the Queen when things threatened to get out of hand. Actually, we had our sights set on visiting Carnaby St and Soho anyway, and were not keen to get entangled on the wrong side of Oxford St.

Recently, Helen and I compared notes on our shared adventures during our teenage years. We revived our memories of that lively weekend. What did we actually get up to in Soho? I thought my diaries might help.

I still have all the schoolgirl diaries that I wrote which cover nearly every year from eleven to eighteen. I keep planning to destroy them because they are so cringe-making, but somehow it does not happen. I read out less-embarrassing-but-still-amusing parts if we have a schoolfriends’ reunion. And they are invaluable for reconstructing what I did and when. Even now they provide me with insights which change my perspective on past events. So I thumbed through 1965, looking for the right entry. And there it was – what two schoolgirls from Birmingham got up to in the heady streets of Soho, in Swinging London.

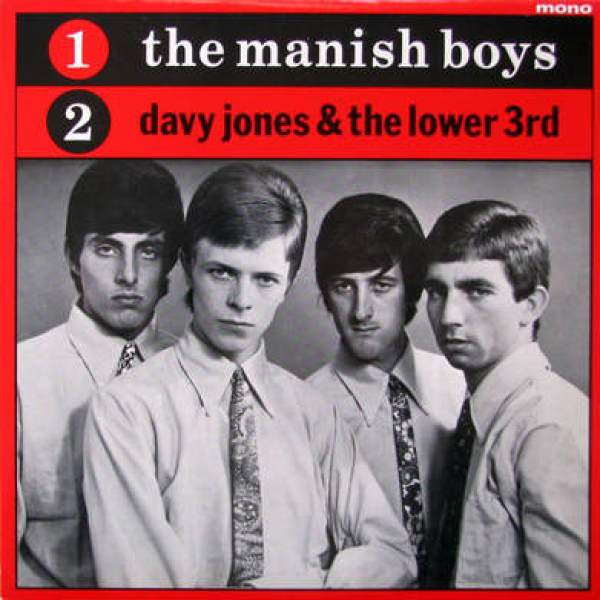

‘Went to Carnaby St but didn’t see anyone interesting. All the boys walking up and down were trying to look famous. The shops were displaying horrible floral ties and swimming trunks. Ugh. Walked to Denmark St (known as ‘Tin Pan Alley’ and the heart of the record industry) …where we met two boys from a supposedly up and coming group called Davy Jones and the Lower Third. One was called Teacup. Bought them cups of tea as they were impoverished. Went back to Carnaby St after lunch and looked in disgust at more floral ties.’

The next day we returned to Soho. It was not that we did not have anything else to do. In fact, we had enjoyed a rather too exciting night. We had neglected to tell our mothers that the YWCA could not have us for the middle night of our visit, and that we had fixed to stay in a flat near Dulwich normally occupied by Diz Disley, a well-known folk and jazz musician. I was deeply into folk music at the time. He had invited us to crash there while he was away. It was a large house with many comings and goings. More specifically, there were some unexpected arrivals in our bedroom during the night, which meant fending off more unwelcome advances. But these particular adventures take up two A4 pages of my diary and I will save them for another time.

Next day, we wandered into Trafalgar Sq where ‘We asked two American beats if they would like to climb up the lions to have their photo taken but they said they did not do that any more. One of them took the camera, pointed it at our stomachs and took a photograph. Then we went to Denmark St again. No sign of the elusive Davy Jones or any of the Lower Third. Had lunch in the café there, two boys called ‘The Ants’ sat at our table. They were quite sweet. One was good-looking and they were chuffed ‘cos they’d made a demo disc.’

So we had met a few young hopefuls, a couple of would-be pop groups. I typed out the account and emailed it off to Helen. She vaguely remembered another of the boys, but he was just one among so many now lost without trace. I agreed, it was doubtful that he had even made a passing wave in recording history. Nevertheless, I thought I would check the ‘elusive’ Davy Jones?

To my astonishment, I found that Davy Jones and the Lower Third had actually released a record shortly afterwards. So they had begun to climb the ladder.

The real surprise was when I read that Davy Jones changed his name to David Bowie. Was he already stepping into the role of the trickster? It is interesting that I had described him as ‘elusive’ in my diary. He was just eighteen and could not have foreseen the meteoric rise to stardom which awaited him.

So this is the story of how I once bought David Bowie a cup of tea in Soho, because he could not afford to pay for his own.”

You may also like to take a look at

So Long, Clive Murphy

My friend and inspiration Clive Murphy died on Wednesday aged eighty-five

Above a curry house in Brick Lane lived Clive Murphy like a wise owl snug in the nest he constructed of books, and lined with pictures, photographs, postcards and cuttings over the nearly fifty years that he occupied his tiny flat. Originally from Dublin, Clive had not a shred of an Irish accent. Instead he revelled in a well-educated vocabulary, a spectacular gift for rhetoric and a dry taste for savouring life’s ironies. He possessed a certain delicious arcane tone that you would recognise if you have heard his fellow-countryman Francis Bacon talking. In fact, Clive was a raconteur of the highest order and I was a willing audience, happy merely to sit at his feet and chuckle appreciatively at his colourful and sometimes raucous observations.

I was especially thrilled to meet Clive because he was a writer after my own heart who made it his business to seek out people and record their stories. At first in Pimlico and then here in Spitalfields through the sixties and seventies, Clive worked as a “modern Mayhew, publishing the lives of ordinary people who had lived through the extraordinary upheavals and social changes of the first three-quarters of the century before they left the stage.” He led me to a bookshelf in his front room and showed me a line of nine books of oral history that he edited, entitled Ordinary Lives, as well as his three novels and six volumes of ribald verse. I was astonished to be confronted with the achievements of this self-effacing man living there in two rooms in such beautiful extravagant chaos.

Naturally, I was immediately curious of Clive’s books of oral history. Each volume is an autobiography of one person recorded and edited by Clive, “ordinary” people whose lives are revealed in the telling to be compelling and extraordinary. They are A Funny Old Quist, memoirs of a gamekeeper, Oiky, memoirs of a pigman, The Good Deeds of a Good Woman, memoirs of an East End hostel dweller, A Stranger in Gloucester, memoirs of an Austrian refugee, Endsleigh, memoirs of a riverkeeper, At the Dog in Dulwich, memoirs of a struggling poet, Four Acres and a Donkey, memoirs of a lavatory attendant, Love, Dears! memoirs of a chorus girl and Born to Sing, memoirs of a Jewish East End mantle presser. The variety of subjects is intriguing and bizarre, and Clive explained his personal vision of creating a social panorama, “to begin with the humblest lavatory attendant and then work my way up in the world until I got to Princess Margaret.”

Much to Clive’s frustration, the project foundered when he got to the middle classes, and he coloured visibly as he explained, “I found the middle classes had an image of themselves they wanted to project and they asked to correct what they had said, afterwards, or they told downright lies, whereas the common people didn’t have an image of themselves and they had a natural gift of language.” I was curious to understand the origin of Clive’s curiosity, and learn how and why he came to edit all these books. And when he told me the story, I discovered the reasons were part of what brought Clive to England in the first place.

“I lived a sheltered life in Dublin in a suburb and qualified as a solicitor before I came to England in 1958. My mother wanted me to be solicitor to Trinity College where her father was Vice-Provost but I had been on two holidays to London and I’d fallen in love with the bright lights. I wanted to see a wider variety of people. So as soon as I qualified I left Dublin, where I had been offered a job as a solicitor at £4 and ten shillings a week, and came to London, where I got a job at once as a liftman at a Lyons Corner House for £8 a week and I have lived here ever since.

I was staying in Pimlico and there was a retired lavatory attendant and his wife who lived down below, and they invited me down for supper. He had such a natural gift for language and a quaint way of expressing himself, so I said ‘Let’s do a book!’ and that was Four Acres and a Donkey. Then I was living in another house and by complete chance there was another retired lavatory attendant, a woman who had once been a chorus girl, so I did another book with her, too, that was Love Dears!

At that time there was an organisation called Space which let out abandoned schools and warehouses to artists. In 1973, I answered their letter in The Times and they found me an empty building, it was the Old St Patrick’s School in Buxton St. I lived in the former headmaster’s study and that’s where I recorded my first East End book. I had nothing but a tea chest, a camp bed and a hurricane lamp. There was no electricity but there was running cold water. Meths drinkers used to sit on the doorstep night and day, and at night they would hammer on the door trying to get in. I was a bit frightened because I had never met meths drinkers before and I was all alone but gradually three artists came to live in the school with me.

Then I had to leave the school house because I was flooded out and, after a stint on Quaker St, I saw an ad in Harry’s Confectioners and moved here to Brick Lane in 1974. The building was owned by a Jewish lady who let the rooms to me and a professor from Rochester University who only came to use his place in vacations, so it was wonderfully quiet. There was a cloth warehouse on the ground floor then which is now the Aladin Restaurant. Every shopfront was a different trade, we had an ironmonger, an electrician and a wine merchant with a sign that said ‘purveyors to the diplomatic service.’ The wine merchant also had a concoction she sold exclusively to the meths drinkers but that wasn’t advertised.

I thought when I came here to Spitalfields I was going to be solely a writer, I had taught at a primary school in Islington but very soon I became a teacher of children with special needs here. Occasionally, I used to go in the middle of the night to buy food from a stall outside Christ Church, Spitalfields called ‘The Silver Gloves.’ I had no money hardly and I used to live off the fruit and veg thrown out by the market onto Brushfield St. But I found it exciting to be here because I found lots of people to interview. I had already written two novels and I was busy recording Alexander Hartog and Beatrice Ali, and I was happy to be learning about them, because I did lead a very restrictive life before I came to England.”

Clive was a poet at heart and there is an unsentimental appreciation of the human condition that runs through all his work. He chose his subjects because he saw the poetry in them when no-one else did and the books, recording the unexpected eloquence of these “ordinary” people telling their stories, bear witness to his compassionate insight.

As a writer writing my own pen portraits, I was curious to ask Clive what he had learnt from all his interviews with such a variety of people. “The gamekeeper said to me, ‘You mean you don’t know how to skin a mole?'” Clive recalled with relish, evoking the gamekeeper in question vividly, before returning to his own voice to explain himself, “I am amazed that we are all stuck in our little worlds – he really thought everyone would know that. It wasn’t just the knowledge that I learnt from people, it was their outlooks and personalities.”

Clive gave me copies of his two East End books and, as we sliced open a box I was delighted to discover “new” copies of books from 1975, beautifully printed in letterpress with fresh unfaded covers and some with a vinyl record inside to allow the reader to hear the voice of the protagonist. I could not wait to go home and read them, and listen.

I will never be able to walk down Brick Lane without thinking of Clive Murphy, who once lived above the Aladin Restaurant, as a beacon of inspiration to me while I am running around Spitalfields pursuing my interviews.

Clive Murphy in his kitchen

You may also like to read

On Missing Mr Pussy

In these dreamy days of high summer, I often think of my old cat Mr Pussy

While Londoners luxuriate in the warmth of summer, I miss Mr Pussy who endured the hindrance of a fur coat, spending his languorous days stretched out upon the floor in a heat-induced stupor.

As the sun reached its zenith, his activity declined and he sought the deep shadow, the cooling breeze and the bare wooden floor to stretch out and fall into a deep trance that could transport him far away to the loss of his physical being. Mr Pussy’s refined nature was such that even these testing conditions provided an opportunity for him to show grace, transcending dreamy resignation to explore an area of meditation of which he was the supreme proponent.

In the early morning and late afternoon, you would see him on the first floor window sill here in Spitalfields, taking advantage of the draught of air through the house. With his aristocratic attitude, Mr Pussy took amusement in watching the passersby from his high vantage point on the street frontage and enjoyed lapping water from his dish on the kitchen window sill at the back of the house, where in the evenings he also liked to look down upon the foxes gambolling in the yard.

Whereas in winter it was Mr Pussy’s custom to curl up in a ball to exclude drafts, in these balmy days he preferred to stretch out to maximize the air flow around his body. There was a familiar sequence to his actions, as particular as stages in yoga. Finding a sympathetic location with the advantage of cross currents and shade from direct light, at first Mr Pussy sat to consider the suitability of the circumstance before rolling onto his side and releasing the muscles in his limbs, revealing that he was irrevocably set upon the path of total relaxation.

Delighting in the sensuous moment, Mr Pussy stretched out to his maximum length of over three feet long, curling his spine and splaying his legs at angles, creating an impression of the frozen moment of a leap, just like those wooden horses on fairground rides. Extending every muscle and toe, his glinting claws unsheathed and his eyes widened gleaming gold, until the stretch reached it full extent and subsided in the manner of a wave upon the ocean, as Mr Pussy slackened his limbs to lie peacefully with heavy lids descending.

In this position that resembled a carcass on the floor, Mr Pussy could undertake his journey into dreams, apparent by his twitching eyelids and limbs as he ran through the dark forest of his feline unconscious where prey were to be found in abundance. Vulnerable as an infant, sometimes Mr Pussy cried to himself in his dream, an internal murmur of indeterminate emotion, evoking a mysterious fantasy that I could never be party to. It was somewhere beyond thought or language. I could only wonder if his arcadia was like that in Paolo Uccello’s “Hunt in the Forest” or whether Mr Pussy’s dreamscape resembled the watermeadows of the River Exe, the location of his youthful safaris.

There was another stage, beyond dreams, signalled when Mr Pussy rolled onto his back with his front paws distended like a child in the womb, almost in prayer. His back legs splayed to either side, his head tilted back, his jaw loosened and his mouth opened a little, just sufficient to release his shallow breath – and Mr Pussy was gone. Silent and inanimate, he looked like a baby and yet very old at the same time. The heat relaxed Mr Pussy’s connection to the world and he fell, he let himself go far away on a spiritual odyssey. It was somewhere deep and somewhere cool, he was out of his body, released from the fur coat at last.

Startled upon awakening from his trance, like a deep-sea diver ascending too quickly, Mr Pussy squinted at me as he recovered recognition, giving his brains a good shake, once the heat of the day had subsided. Lolloping down the stairs, still loose-limbed, he strolled out of the house into the garden and took a dust bath under a tree, spending the next hour washing it out and thereby cleansing the sticky perspiration from his fur.

Regrettably the climatic conditions that subdued Mr Pussy by day, also enlivened him by night. At first light, when the dawn chorus commenced, he stood on the floor at my bedside, scratched a little and called to me. I woke to discover two golden eyes filling my field of vision. I rolled over at my peril, because this provoked Mr Pussy to walk to the end of the bed and scratch my toes sticking out under the sheet, causing me to wake again with a cry of pain. I miss having no choice but to rise, accepting his forceful invitation to appreciate the manifold joys of early morning in summer in Spitalfields, because it was not an entirely unwelcome obligation.

You may also like to read

Mr Pussy Gives his First Interview

Click here to order a copy for £10

Nicholas Borden’s Lockdown Paintings Exhibition

I am delighted to announce that, following the tremendous response to Nicholas Borden’s recent paintings on Spitalfields Life, these will now be exhibited in a one man show entitled, WISHFUL THINKING, Nicholas Borden’s Lockdown Paintings at Townhouse Spitalfields, opening this Saturday 19th June and running until Sunday 4th July. (Paintings will also be for sale from the website from 19th June.)

Nicholas & I met up for a celebratory chat recently and he talked more about some of his paintings.

“I prefer to work outside but it is something I have only done in recent years, before that decision I think I was lost creatively. I like to observe things and be able to respond spontaneously. I tend to work quickly and not be premeditated.

For me, there is no substitute for working from life even if you have to deal with a lot of curious onlookers, that is why I try to work as early as I can in the day. On the street, you are painting in challenging circumstances and anything can happen but mostly people are encouraging. In future, I would like to simplify my compositions to create visions. Alfred Wallis was a great artist who was able to do that.

I felt cut off in Lockdown, so I listened to the radio a lot. I got by the best I could by being as busy as I could with my painting. I had a structure and a routine, and I worked on several paintings at a time. There were less people about, especially in Central London. I had never seen anything like it, almost apocalyptic. I hope we never live through anything like that again.

Painting helped me get through it and I am very lucky that I experienced no illness. Painting gave me strength and independence, and a new way of looking. During Lockdown, painting became the expression of my emotions. I think it made me a better painter.”

Nicholas Borden

Arnold Circus, Boundary Estate

I could not go home to visit my family in Devon over Christmas because of the Lockdown and it was a pretty lonely experience, so I painted this winter view of Arnold Circus in Shoreditch. It is not grim, it is a beautiful place and there is a lot of colour. I am aware of the campaign to Save Arnold Circus from tearing up the old paving and redesigning it, so I was inspired to paint this. It is a spectacular circular park with the original bandstand dating from 1900.

Wishful Thinking, gardens near Victoria Park

This is a view near where I live. It was hard to finish this painting because people were concerned that I was looking into their back gardens, but it is not against the law is it?

View from St Augustine’s Tower, Hackney

I have to thank St John in Hackney for giving me permission to use St Augustine’s Tower. They gave me the key and I had it for several weeks last summer, but it was exhausting climbing up a hundred steps every day to the roof. This was the first painting I did there, looking north-west towards Upper Clapton. In the foreground is the pedestrianised Narrow Walk and in the left hand corner is part of Marks & Spencer. I found I can compose work better when I am looking from high up.

Getting a bit of fresh air, Church St, Stoke Newington

This is next to Abney Park Cemetery where General Booth who founded the Salvation Army is buried. It is a spectacular cemetery. I painted it in winter and I was attracted to this gothic subject. It was raining but I saw a lot of new mothers walking up and down with their babies, getting a bit of fresh air.

Regent’s Canal at Victoria Park

I used a lot of ochre and Prussian blue in this painting. It was a winter’s day just after Christmas and I remember being very cold. From Victoria Park, I had this view across Regent’s Canal into the back gardens and I liked the composition. You can see into people’s lives. It is all revealed in the busy detail of sheds, washing hanging up and an abandoned greenhouse.

Feeding the pigeons near Mare St

This alleyway with a green area is quite close to where I live and feeding the pigeons became a bit of an issue during Lockdown. There is a rogue character who feeds them obsessively which has drawn controversy locally. I do not have any beef with it, but people who live nearby object and this painting typifies that tension.

St John of Jerusalem, Hackney

Someone chucked some water over me while I was doing this painting, just a sprinkle. I told my neighbour and he said, ‘Let’s go and sort them out,’ but I think it was intended as a joke. I have walked past this church thousands of times but I have never been inside. I have a Samuel Palmeresque feeling about it. He used strong yellows and liked romantic trees. Me and my brother used to be in the choir at our village church and we had to listen to sermons and the priest was completely mad. Maybe that was in the back of my mind when I painted this?

The Lake, Victoria Park

This is a winter scene at the lake. I come from the country originally and I like going for walks, so I think that is why I am constantly drawn back to the park, seeking peace and tranquility in the city.

Well St Common, Hackney

This painting has a domestic quality for me, Well Street Common is just round the corner from my flat in Hackney. I do not have a garden, so during Lockdown I found it relaxing to go there to read books and I always see people out playing ball games. I wanted the gardens to form a backdrop and this was painted in the evening because I wanted the long shadows. I thought it had a timeless quality.

Regent’s Canal at Old Ford Rd

Regent’s Canal at Victoria Park

This painting was produced over several days just before spring arrived. I try to go first thing on consecutive mornings at the same time, when it is still quiet. There is so much activity in Victoria Park and it is a long-established park that has not changed in all these years. That is part of its appeal for me. People always enjoy being outside and this was especially important during Lockdown.

St James’s Park, Westminster

Christ Church, Spitalfields

Ever since I first saw Christ Church, I recognised this was a striking piece of architecture. It has been painted by many artists before me, including Leon Kossoff and John Piper. It is an especially challenging subject, structurally and proportionally.

I remember painting this very early last summer, I tried to work quickly and directly because the light changes. You only have a span of around two hours before the light is so different you can no longer work, especially if you have long shadows. For me, the summer plumage of the tree brings joy to this image.

River Lea at Clapton

This was painted from the Lea Bridge. I like John Constable and I was thinking of him and of British landscape painting, although I am aware of the need to find your own vision.

Paintings copyright © Nicholas Borden

You may also like to take a look at

Nicholas Borden’s Latest Paintings

Catching Up With Nicholas Borden

Nicholas Borden’s East End View

Nicholas Borden’s Winter Paintings

Nicholas Borden’s Spring Paintings