Receipts From London’s Oldest Ironmonger

As any accountant will tell you – you must always keep your receipts. It was a dictum adopted religiously by the staff at London oldest ironmongers R. M. Presland & Sons in the Hackney Rd from 1797-2013, where this cache of receipts from the eighteen-eighties and nineties was discovered. All these years later, they may no longer be of interest to the tax man, but they serve to illustrate the utilitarian beauty of nineteenth-century typographic design and tell us a lot about the diverse interrelated trades which once filled this particular corner of the East End.

You may also like to read about

Clive Murphy, Phillumenist

I am celebrating my friend, the late Clive Murphy, by publishing his matchbox label collection

Clive Murphy, Phillumenist

Nothing about this youthful photo of the novelist, oral historian and writer of ribald rhymes, Clive Murphy – resplendent here in a well-pressed tweed suit and with his hair neatly brushed – would suggest that he was a Phillumenist. Even people who had known him since he came to live in Spitalfields in 1973 never had an inkling. In fact, evidence of his Phillumeny only came to light when Clive donated his literary archive to the Bishopsgate Institute and a non-descript blue album was uncovered among his papers, dating from the era of this picture and with the price ten shillings and sixpence still written in pencil in the front.

I was astonished when I saw the beautiful album and so I asked Clive to tell me the story behind it. “I was a Phillumenist,” he admitted to me in a whisper, “But I broke all the rules in taking the labels off the matchboxes and cutting the backs off matchbooks. A true Phillumenist would have a thousand fits to see my collection.” It was the first time Clive had examined his album of matchbox labels and matchbook covers since 1951 when, at the age of thirteen, he forsook Phillumeny – a diversion that had occupied him through boarding school in Dublin from 1944 onwards.

“A memory is coming back to me of a wooden box that I made in carpentry class which I used to keep them in, until I put them in this album,” said Clive, getting lost in thought, “I wonder where it is?” We surveyed page after page of brightly-coloured labels from all over the world pasted in neat rows and organised by their country of origin, inscribed by Clive with blue ink in a careful italic hand at the top of each leaf. “I have no memory of doing this.” he confided to me as he scanned his handiwork in wonder,“Why is the memory so selective?”

“I was ill-advised and I do feel sorry in retrospect that they are not as a professional collector would wish,” he concluded with a sigh, “But I do like them for all kinds of other reasons, I admire my method and my eye for a pattern, and I like the fact that I occupied myself – I’m glad I had a hobby.”

We enjoyed a quiet half hour, turning the pages and admiring the designs, chuckling over anachronisms and reflecting on how national identities have changed since these labels were produced. Mostly, we delighted at the intricacy of thought and ingenuity of the decoration once applied to something as inconsequential as matches.

“There was this boy called Spring-Rice whose mother lived in New York and every week she sent him a letter with a matchbox label in the envelope for me.” Clive recalled with pleasure, “We had breaks twice each morning at school, when the letters were given out, and how I used to long for him to get a letter, to see if there was another label for my collection.” The extraordinary global range of the labels in Clive’s album reflects the widely scattered locations of the parents of the pupils at his boarding school in Dublin, and the collection was a cunning ploy that permitted the schoolboy Clive to feel at the centre of the world.

“You don’t realise you’re doing something interesting, you’re just doing it because you like pasting labels in an album and having them sent to you from all over the world.” said Clive with characteristic self-deprecation, yet it was apparent to me that Phillumeny prefigured his wider appreciation of what is otherwise ill-considered in existence. It was a sensibility that found full expression in Clive’s exemplary work as an oral historian, recording the lives of ordinary people with scrupulous attention to detail, and editing and publishing them with such panache.

Clive Murphy, Phillumenist

Images courtesy of the Clive Murphy Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read

Clive Murphy’s Snaps

I am celebrating my friend, the late Clive Murphy, by publishing his snaps

Pauline, Animal Lover, 77 Brick Lane, 16 July 1988

When it comes to photography, Clive Murphy – the novelist, oral historian and writer of ribald rhymes – modestly described himself as a snapper. Yet although he used the term to indicate that his taking pictures was merely a casual preoccupation, I prefer to interpret Clive’s appellation as meaning “a snapper up of unconsidered trifles” – one who cherishes what others disregard.

“I carried it around in my shoulder bag and if something interested me, I would pull out my camera and snap it,” Clive informed me plainly, “I am a snapper because I work instinctively and I rely entirely upon my eye for the picture.”

In thousands of snapshots, every one labelled on the reverse in his spidery handwriting and organised into many shelves of numbered volumes, Clive chronicled the changing life of Spitalfields, of those around him and of those he knew, since he came to live above the Aladin Restaurant on Brick Lane in 1973. These pictures are not those of a documentary photographer on assignment but the intimate snaps of a member of the community, and it is this personal quality which makes them so compelling and immediate, drawing the viewer into Clive’s particular vivid universe in Spitalfields.

One day, we pulled out a few albums and leafed through the pages together, selecting a few snaps to show you, and Clive told me some of the stories that go with them.

Brick Lane, May 1988

Komor Uddin, Taj Stores, 7 December 1990

Columbia Rd Market, 13 November 1988

Jasinghe Ranamukadewasa Fernando (known as Vijay Singh), Holy Man with acolyte, Brick Lane, March 1988 – “Many people in Brick Lane thought he was the new Messiah and the press came down in droves. He was regarded as a very holy man, he held court in the Nazrul Restaurant and people took his potions and remedies. When he died, I joined the crowd to see his body at the Co-op Funeral Parlour in Chrisp St.”

Clive Murphy’s cat Pushkin, 132 Brick Lane, July 1988 – “Pushkin followed me down Brick Lane from Fournier St one night and, when I opened my hall door, he came in with me. So he adopted me, when he was only a kitten and could hardly jump up a step. And I had him for twenty years.”

Neighbour’s doves hoping to be fed, 16 March 1991 – “The Nazrul Restaurant used to keep doves and, when they disappeared, Pushkin was blamed but I assure you he had nothing to do with it.”

Kyriacos Kleovoulou, Barber, Puma Court, 23 February 1990 – “I’ve had a few haircuts there in the past.”

Waiter, Nazrul Restaurant, Brick Lane, 29 May 1988

Harry Fishman, 97 Brick Lane, 19 September 1987 – “He was a godsend to everybody because he cashed any cheque on the spot. I think he was used to being robbed, so he wanted to get rid of the cash. Harry Fishman was the most-loved man on Brick Lane in the seventies, his shop was always full of people wanting to be around him, and I often delivered papers to The Golden Heart for him.”

Harry Fishman’s shop, corner of Quaker St, 19 September 1987

Window Cleaning, Woodseer St, March 1988 – “This man used to run an orchestra and, at all dances and Bengali events, they would play.”

Sunday use of Weinbergs (sold), November 1987 – “It was a printers and when it closed it became a fruit stall. Mr Weinberg was a very jolly fat man, slightly balding, who ordered his staff about. He would say things like, ‘Left, right, left, right, do it properly!’ I dined at his house and I didn’t like the cover of my first novel, so I asked him to redesign it for me. He had a nephew who had never been with a woman and he asked me to find him an escort agency. We all dined in a restaurant behind the Astoria Theatre in the Charing Cross Rd, and then I let them use my front room. But after an hour she came out and said, ‘It’s no use, I give up!’ but we still had to pay, and his nephew never became a man.”

Christ Church Night Tea Stall, October 1987 – “I always went out as the last thing I did before I went to bed, to have a snack.”

Clive’s landlord, Toimus Ali, at The Aladin Restaurant, 6 March 1991 – “He was very taciturn.”

Fournier St, 7 February 1991 – “I used to come here and have lunch with all the taxi-drivers who loved it so much.”

Retired street cleaner, Brick Lane, March 1988

Tramp, Brick Lane, 29 May 1988

Pushkin unwell, Jan 4 1991 – “I was told it would be quite alright to feed my cat on frozen whitebait, but I didn’t thaw it properly and it killed my Pushkin.”

Harry Fishman’s shop after closure, 97 Brick Lane, 27 September 1987

Clive at his desk, 132 Brick Lane, 31 December 1989

Photographs courtesy of the Clive Murphy Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to read my other stories about Clive Murphy

Simon Pettet’s Tiles At Dennis Severs’ House

I am delighted to announcement Dennis Severs’ House reopens on 29th July. Click here to book

Anyone who has ever visited Dennis Severs’ House will recognise this spectacular chimneypiece in the bedroom with its idiosyncratic pediment designed to emulate the facade of Christ Church, Spitalfields.

The fireplace itself is lined with an exquisite array of delft tiles which you may have admired, but very few people today know that these tiles were made by craftsman Simon Pettet in 1985, when he was twenty years old and living in the house with Dennis Severs. Simon was a gifted ceramicist who mastered the technique of tile-making with such expertise that he could create new delft tiles in the authentic manner which were almost indistinguishable from those manufactured in the seventeenth century.

In his tiles for this fireplace, Simon made a witty leap of the imagination, using them to create a satirical gallery of familiar Spitalfields personalities from the nineteen eighties. Today his splendid fireplace of tiles exists as a portrait of the neighbourhood at that time, though so discreetly done that unless someone pointed it out to you, it is unlikely you would ever notice amongst all the other beguiling details of Dennis Severs’ House.

Simon Pettet died of AIDS in 1993, eight years after completing the fireplace and just before his twenty-eighth birthday, and today his ceramics, especially this fireplace in Dennis Severs’ House, comprise an intriguing and poignant memorial to remind us of a short but extremely productive life. Simon’s death imparts an additional resonance to the humour of his work now, which is touching in the skill he expended to conceal his ingenious achievement. As with so much in these beautiful old buildings, we admire the workmanship without ever knowing the names of the craftsmen who were responsible and Simon aspired to this worthy tradition of anonymous artisans in Spitalfields.

Once I learnt the story, I wanted to go over to Folgate St and take a look for myself. And when I squatted down to peer into the fireplace, I could not help smiling at once to recognise Gilbert & George on the very first tile I saw. Simon had created instantly recognisable likenesses that also recalled Tenniel’s illustrations of Tweedledum & Tweedledee. Most importantly, the spontaneity, colour, texture and sense of line were all exactly as you would expect of a delft tile. Taking my camera and tripod in hand, I spent a couple of happy hours with my head in the fireplace before emerging sooty and triumphant with this selection of photographs of Simon’s tiles for you to enjoy. Reputedly, there is a portrait of Dan Cruickshank, but it must be hidden behind the fire irons because I could not find it that day.

When I had almost finished photographing all the tiles, I noticed one placed at the top right-hand side that was entirely hidden from the viewer by the wooden surround on the front of the fireplace. It was almost completely covered in soot too, but I used a kitchen scourer to remove the grime and discovered this most-discreetly placed tile was a portrait of Simon himself at work making tiles. The modesty of the man was such that only someone who climbed into the fireplace, as I did, would ever find Simon’s own signature tile.

Gilbert & George

Raphael Samuel, foremost historian of the East End

Ricardo Cinalli, artist

Jim Howett, furniture maker, whom Dennis Severs saw as the fly on the wall in Spitalfields

Ben Langlands & Nikki Bell, two artists who made money on the side as housepainters

Simon De Courcy Wheeler, photographer

Julian Humphreys, who renovated his bathroom regularly, “Tomorrow is another day”

Scotsman, Paul Duncan, who worked for the Spitalfields Trust

Douglas Blain, director of the Spitalfields Trust, who was devoted to Hawksmoor

The individuals portrayed in this notorious incident in Folgate St cannot be named for legal reasons

Keith and Jane Bowler of Wilkes St

Her Majesty the Cat, known as “Madge,” watching “Come Dancing”

Marianna Kennedy and Ian Harper, who were both students at the Slade

Rodney Archer with his mother Phyllis, of Fournier St

Anna Skrine, secretary of the Spitalfields Trust

Simon’s discreetly place self-portrait

The fireplace Simon Pettet made for Martin Lane’s house in Elder St, with the order of service for Simon’s funeral tucked behind

Simon Pettet, designer and craftsman (1965-93)

Tom & Jerry’s Life In London

This frontispiece was intended to illustrate the varieties of “Life in London,” from the king on his throne at the top of the column to the lowest members of society at the base. At the centre are the protagonists of the tale, Tom, Jerry & Logic, three men about town. Authored by Pierce Egan, their adventures proved best sellers in serial form and were collected into a book in 1820, remaining in print for the rest of the century, spawning no less than five stage versions, and delineating a social landscape that was to prove the territory for both the fictions of Charles Dickens and the commentaries of Henry Mayhew.

Accounts of the urban poor and of life in the East of London are scarce before the nineteenth century, and what makes “Life in London” unique is that it portrays and contrasts the society of the rich and the poor in the metropolis at this time. And, although fictional in form, there is enough detail throughout to encourage the belief that this is an authentic social picture.

The characters of Tom, Jerry & Logic were loosely based upon the brothers who collaborated upon the illustrations, Isaac Richard & George Cruickshank, and the writer Pierce Egan, all relishing this opportunity to dramatise their own escapades for popular effect. Isaac Richard & George’s father had enjoyed a successful career as a political cartoonist in the seventeen-nineties and it was his sons’ work upon “Life in London” that brought the family name back into prominence in the nineteenth century, leading to George Cruikshank’s long term collaboration with Charles Dickens.

Jerry Hawthorn comes up from the country to enjoy a career of pleasure and fashion with Corinthian Tom, yet as well as savouring the conventional masquerades, exhibitions and society events, they visit boxing matches, cockpits, prisons and bars where the poor entertain themselves, with the intention to “see a ‘bit of life.” It is when they grow weary of fashionable society, that the idea arises to see a “bit of Life” at the East End of the Town.” And at “All Max,” an East End boozer, they discover a diverse crowd, or as Egan describes it, “every cove that put in an appearance was quite welcome, colour or country considered no obstacle… The group was motley indeed – Lascars, blacks, jack-tars, coal-heavers, dustmen, women of colour, old and young, and a sprinkling of the remnants of once fine girls, and all jigging together.” In the Cruikshanks’ picture, Logic has Black Sall on one knee and Flashy Nance upon the other while Jerry pours gin into the fiddler and Tom carouses with Mrs Mace, the hostess, all revealing an unexpectedly casual multiracial society in which those of different social classes can apparently mix with ease.

Situated somewhere between the romps of Fielding, Smollet and Sterne and prefiguring Dickens’ catalogue of comic grotesques in “Pickwick Papers,” the humour of “Life in London,” spoke vividly to its time, yet appears merely curious two centuries later. By the end of the nineteenth century, the comedy had gone out of date, as Thackeray admitted even as he confessed a lingering affection for the work. “As to the literary contents of the book, they have passed clean away…” he wrote, reserving his enthusiasm for the illustrations by the Cruikshank brothers – which you see below – declaring,“But the pictures! Oh! The pictures are noble still!”

Lowest life in London – Tom, Jerry & Logic amongst the unsophisticated sons & daughters of nature in the East.

The Royal Exchange – Tom pointing out to Jerry a few of the primest features of life in London.

A Whistling Shop – Tom & Jerry visiting Logic “on board the fleet.”

Tom, Jerry & Logic “tasting” wine in the wood at the London Dock.

White Horse Cellar, Picadilly – Tom & Logic bidding Jerry “Good bye.”

Jerry “beat to a standstill” Dr Please’ems’ prescription.

Tom & Jerry “masquerading it” among the cadgers in the back slums.

“A shilling well laid out” – Tom & Jerry at the exhibition of pictures at the Royal Academy.

Tom, Jerry & Logic backing Tommy, the ‘sweep at the Royal Cockpit.

Tom, Jerry & Logic in characters at the Grand Carnival.

Symptoms of the finish of “some sorts of life” – Tom, Jerry & Logic in the Press Yard at Newgate.

Life in London – Peep ‘o day boys, a street row. the author losing his “reader.” Tom & Jerry showing fight and Logic floored.

The “ne plus ultra” of Life in London – Kate, Sue, Tom, Jerry & Logic viewing the throne room at Carlton Palace.

Tom & Jerry catching Kate & Sue on the sly, having their fortunes told.

Jerry’s admiration of Tom in an “assault” with Mr O’Shannessy at the rooms in St James’ St.

Tom introducing Jerry & Logic to the champion of England.

The art of self-defence – Tom & Jerry receiving instruction from Mr Jackson.

Tom & Jerry larking at a masquerade supper at the Opera House.

Tom & Jerry in trouble after a spree.

Jerry in training for a “swell.”

Tom & Jerry taking blue ruin after the spell is broke up.

Life in the East. At the Half Moon Tap – Tom, Jerry & Logic called to the bar by the Benchers. The John Bull Fighter exhibiting his cups and ‘the uncommonly big Gentleman’ highly amused by the originality of the surrounding group.

The Mistakes of a Night. The Hotel in an Uproar. Tom, sword in hand backed by a Petticoat – “False Alarm!” but no Ghost.

Logic’s slippery state of Affairs. A Random Hit! and the Upper Works of Old Thatchpate not insured. And the fat Knight enjoying the Scene laughing, like Fun, at Logic’s disaster.

Hawthorn Hall. Jerry at Home: the Enjoyments of a comfortable fireside. Logic all Happiness. Corinthian Tom at his Ease. The Old Folks in their Glory, and the ‘uncommonly big Gentleman’ taking forty winks.

The Hounds at a Standstill. Jerry enticed by the pretty Gipsy Girl to have his fortune told.

Logic’s Upper Storey but no Premises. Jerry’s Return to the Metropolis.

Strong Symptoms of Water on the Brain in the Floating Capital.

The Duchess of Do-Good’s Screen, an attractive subject to Tom & Jerry

How to Finish a Night, to be Up and dressed in the Morning. Tom awake, Jerry caught napping and Logic on the go.

Splendid Jem, once a dashing Hero in the Metropolis, recognised by Tom amongst the Convicts in the Dockyard at Chatham.

Logic visiting his old Acquaintances on board the Fleet, accompanied by Tom & Jerry to play a Match at Rackets with Sir John Blubber.

Jerry up, but not dressed! A miserable Brothel, his Pal bolted with the Togs. One of those unfortunate Dilemmas connected with Life in London, arising from the Effects of Inebriety.

The Burning Shame! Tom & Jerry laughing at the Turn-up between the ‘uncommonly big Gentleman’ and the Hero of the Roundyken under suspicious Circumstances.

The Money Lender. The ‘High-Bred One’ trying it on, to get the best of the Old Screw, to raise the Needful towards Life in London, accompanied by Tom, Jerry & Logic.

Popular Gardens. Tom, Jerry & Logic laughing at the Bustle and Alarm occasioned amongst the Visitors by the Escape of a Kangaroo.

Life on the Water. Symptoms of a Drop too much for the ‘uncommonly big Gentleman.’

Melancholy End of Corinthian Kate! One of those lamentable Examples of a dissipated Life in London.

The Death of Corinthian Tom

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Insitute

You may like to look at these other sets of pictures by George Cruikshank

Jack Sheppard, Thief, Highwayman & Escapologist

Charles Skilton’s London Life, 1950

Now that the summer is here, I thought I would send you this fine set of postcards published by Charles Skilton, including my special favourites the escapologist and the pavement artist.

Looking at these monochrome images of the threadbare postwar years, you might easily imagine the photographs were earlier – but Margaret Rutherford in ‘Ring Round the Moon’ at The Globe in Shaftesbury Ave in number nine dates them to 1950. Celebrated in his day as publisher of the Billy Bunter stories, Charles Skilton won posthumous notoriety for his underground pornographic publishing empire, Luxor Press.

You may also like to take a look at

The Secrets Of Christ Church

There is a such a pleasing geometry to the architecture of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Christ Church, Spitalfields, completed in 1729, that when you glance upon the satisfying order of the facade you might assume that the internal structure is equally apparent. Yet it is a labyrinth inside. Like a theatre, the building presents a harmonious picture from the centre of the stalls, yet possesses innumerable unseen passages and rooms, backstage.

Beyond the bellringers’ loft, a narrow staircase spirals further into the thickness of the stone spire. As you ascend the worn stone steps within the thickness of the wall, the walls get blacker and the stairs get narrower and the ceiling gets lower. By the time you reach the top, you are stooping as you climb and the giddiness of walking in circles permits the illusion that, as much as you are ascending into the sky, you might equally be descending into the earth. There is a sense that you are beyond the compass of your experience, entering indeterminate space.

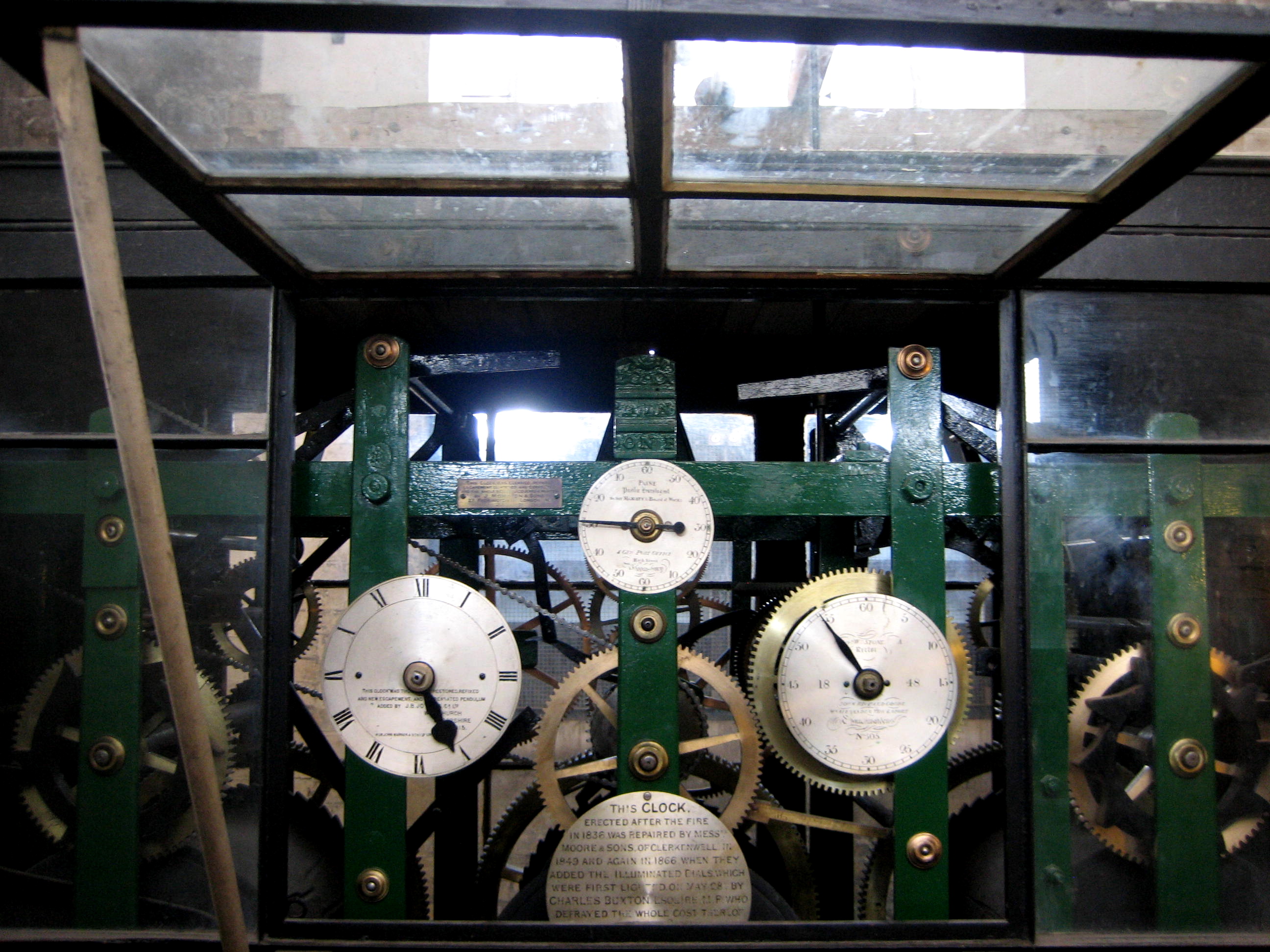

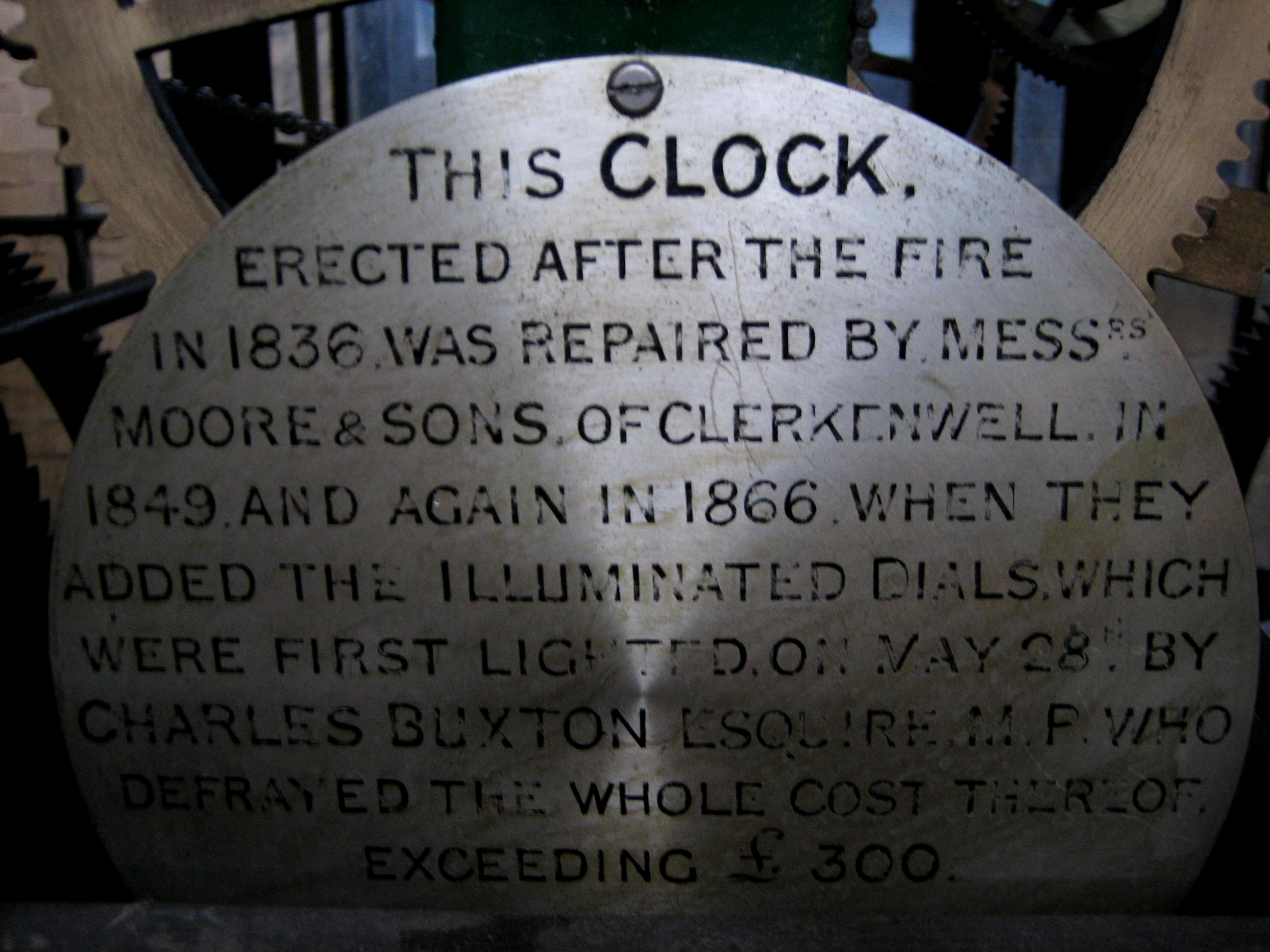

No-one has much cause to come up here and, when we reached the door at the top of the stairs, the verger was unsure of his keys. As I recovered my breath from the climb, while he tried each key in turn upon the ring until he was successful, I listened to the dignified tick coming from the other side of the door. When he opened the door, I discovered it was the sound of the lonely clock that has measured out time in Spitalfields since 1836 from the square room with an octagonal roof beneath the pinnacle of the spire. Lit only by diffuse daylight from the four clock faces, the renovations that have brightened up the rest of the church do not register here.

Once we were inside, the verger opened the glazed case containing the gleaming brass wheels of the mechanism, turning with inscrutable purpose within their green-painted steel cage, driving another mechanism in a box up above that rotates the axles, turning the hands upon each of the clock faces. Not a place for human occupation, it was a room dedicated to time and, as intervention is required only rarely here, we left the clock to run its course in splendid indifference.

By contrast, a walk along the ridge of the roof of Christ Church, Spitalfields, presented a chaotic and exhilarating symphony of sensations, buffered by gusts of wind beneath a fast-moving sky that delivered effects of light changing every moment. It was like walking in the sky. On the one hand, Fashion St and on the other Fournier St, where the roofs of the ighteenth century houses topped off with weavers’ lofts create an extravagant roofscape of old tiles and chimney pots at odd angles. Liberated by the experience, I waved across the chasm of the street to residents of Fournier St in their rooftop gardens opposite, just like waving to people from a train.

Returning to the body of the church, we explored a suite of hidden vestry rooms behind the altar, magnificently proportioned apartments to encourage lofty thoughts, with views into the well-kept rectory garden. From here, we descended into the crypt constructed of brick vaults to enter the cavernous spaces that until recent years were stacked with human remains. Today these are innocent, newly-renovated spaces without any tangible presence to recall the thousands who were laid to rest here until it was packed to capacity and closed for burial in 1812 by Rev William Stond MA, as confirmed by a finely lettered stone plaque.

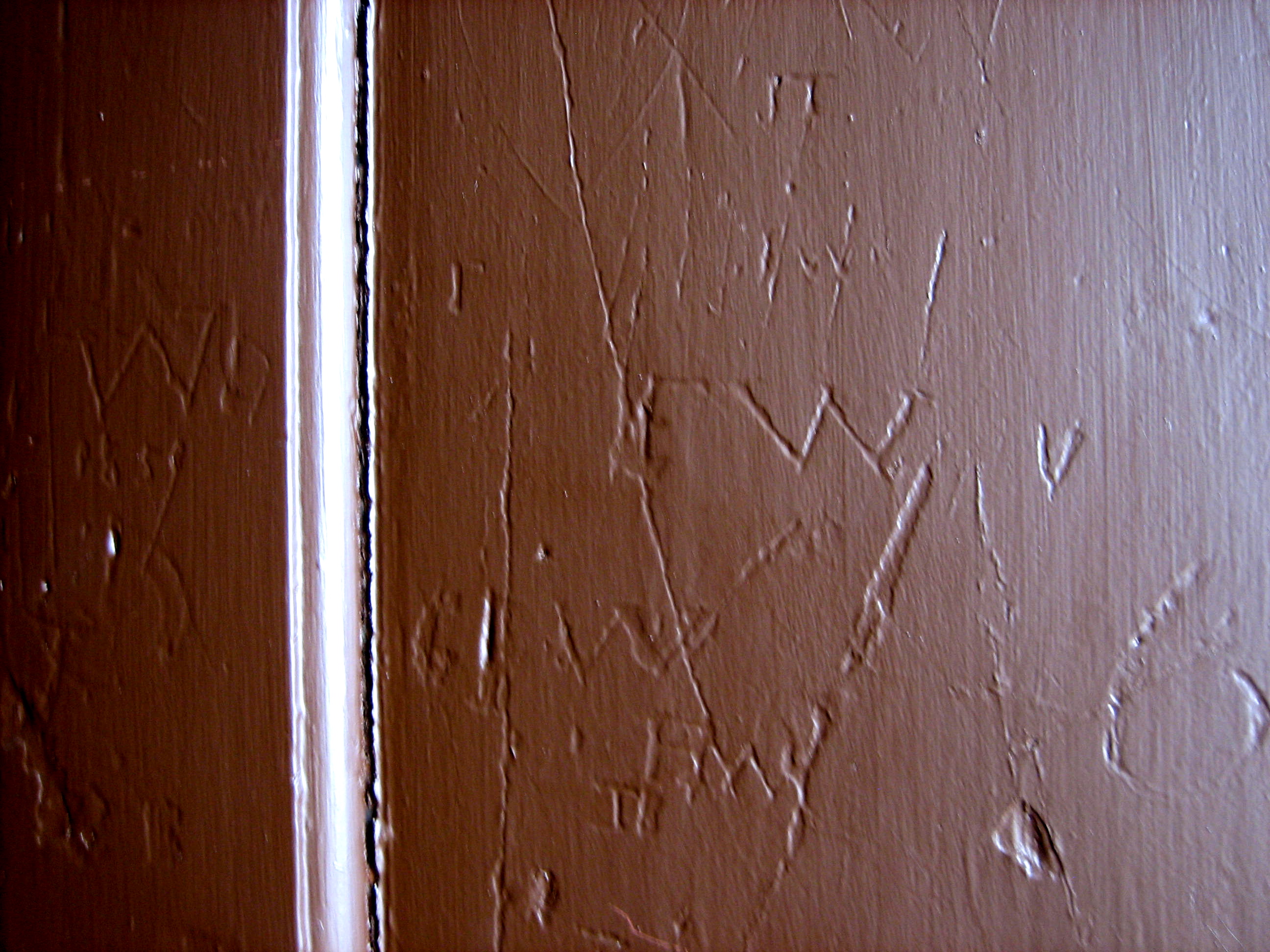

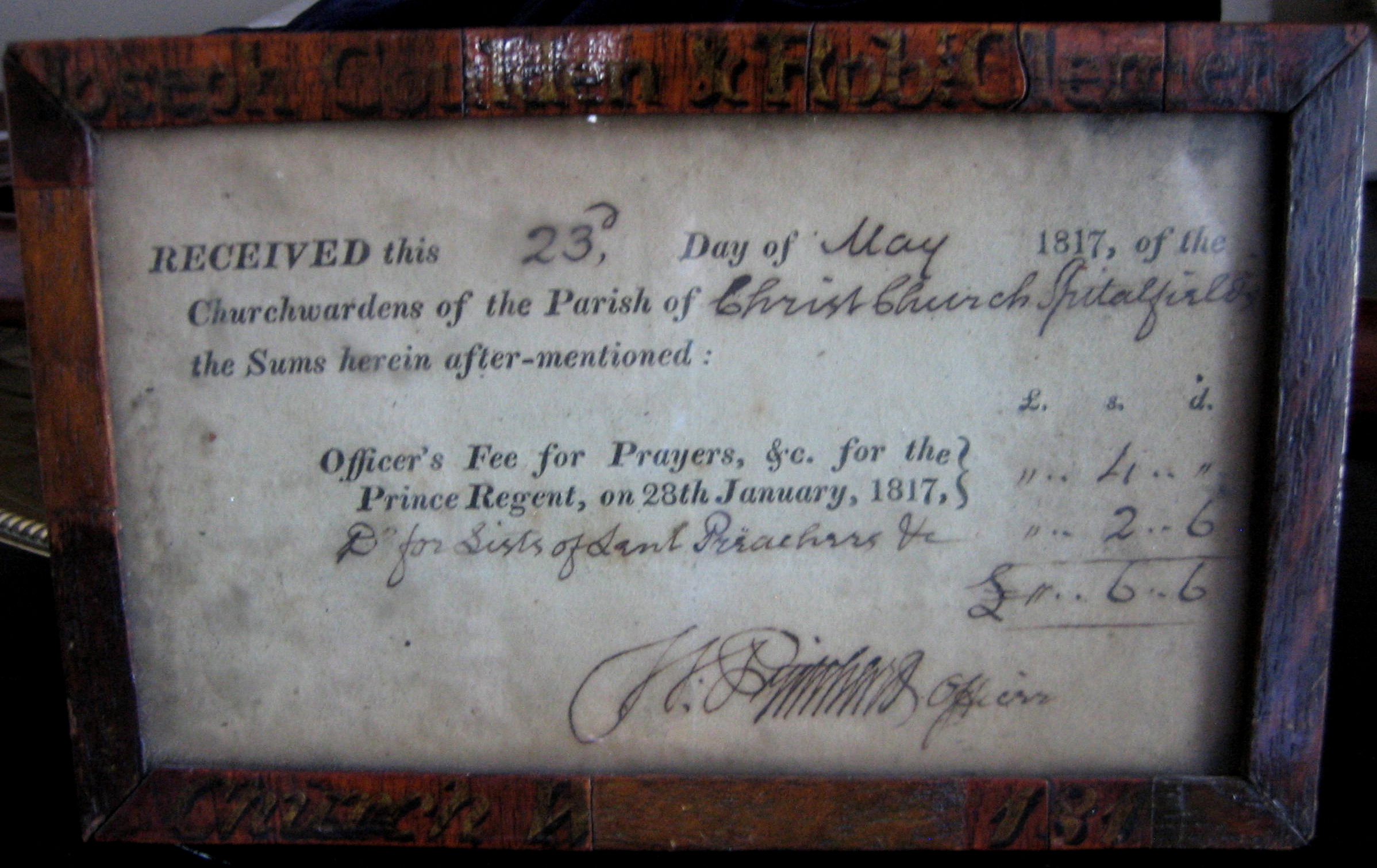

Passing through the building, up staircases, through passages and in each of the different spaces from top to bottom, there were so many of these plaques of different designs in wood and stone, recording those were buried here, those who were priests, vergers, benefactors, builders and those who rang the bells. In parallel with these demonstrative memorials, I noticed marks in hidden corners, modest handwritten initials, dates and scrawls, many too worn or indistinct to decipher. Everywhere I walked, so many people had been there before me, and the crypt and vaults were where they ended up.

My visit started at the top and I descended through the structure until I came, at the end of the afternoon, to the small private vaults constructed in two storeys beneath the porch, where my journey ended, as it did in a larger sense for the original occupants. These delicate brick vaults, barely three feet high and arranged in a crisscross design, were the private vaults of those who sought consolation in keeping the family together even after death. All cleaned out now, with modern cables and pipes running through, I crawled into the maze of tunnels and ran my hand upon the vault just above my head. This was the grave where no daylight or sunshine entered, and it was not a place to linger on a bright afternoon in May.

Christ Church gave me a journey through many emotions, and it fascinates me that this architecture can produce so many diverse spaces within one building and that these spaces can each reflect such varied aspects of the human experience, all within a classical structure that delights the senses through the harmonious unity of its form.

The mechanism of this clock runs so efficiently that it only has to be wound a couple of times each year

Looking up inside the spire

A model of the rectory in Fournier St

On the reverse of the door of the organ cupboard

In the vestry

For nearly three centuries, the shadow of the spire has travelled the length of Fournier St each afternoon

You may also like to read about