Luke Clennell’s Dance of Death

Twenty years have passed since my father died at this time of year and thoughts of mortality always enter my mind as the nights begin to draw in, as I prepare to face the spiritual challenge of another long dark winter ahead. So Luke Clennell’s splendid DANCE OF DEATH engravings inspired by Hans Holbein suit my mordant sensibility at this season.

First published in 1825 as the work of ‘Mr Bewick’, they have recently been identified for me as the work of Thomas Bewick’s apprentice Luke Clennell by historian Dr Ruth Richardson.

The Desolation

The Queen

The Pope

The Pope

The Cardinal

The Elector

The Canon

The Canoness

The Priest

The Mendicant Friar

The Councillor or Magistrate

The Councillor or Magistrate

The Astrologer

The Physician

The Merchant

The Wreck

The Swiss Soldier

The Charioteer or Waggoner

The Porter

The Porter

The Fool

The Miser

The Miser

The Gamesters

The Gamesters

The Drunkards

The Beggar

The Thief

The Newly Married Pair

The Husband

The Wife

The Child

The Old Man

The Old Woman

You may also like to take a look at

Geraldine Beskin, Witch

Geraldine Beskin presides as serenely as the Mona Lisa from behind her desk at the Atlantis Bookshop in Museum St, Bloomsbury – the oldest occult bookshop in the world, one of London’s unchanging landmarks and the pre-eminent supplier of esoteric literature to the great and the good, the sinister and the silly, since 1922. “My father came into the shop one day and Michael Houghton, a poet and a magician, who founded it and knew everyone from W.B.Yeats to Aleister Crowley, took a good look at him and said, ‘You’ll own this place one day,'” Geraldine told me, with a gentle smile that indicated a relaxed acceptance of this happy outcome as indicative of the natural order of things.

“I started working here when I was nineteen, and I’ve read a tremendous amount and I’ve done some of it – because you have to be a reader to be a good bookseller,” she said, casting her eyes around with proprietary affection at the sage green shelves lined with diverse and colourful books old and new, organised in alphabetical categories from angels and fairies, by way of magic and paganism, to werewolves and vampires.“This place was set up by magicians for magicians and that’s a tradition we continue today,” boasted Geraldine, who guards this treasure trove with her daughter Bali, the third generation in the book trade and a fourth generation occultist.

Yet in spite of the exoticism of her subject matter, Geraldine recognises the necessity for a certain rigour of approach.“There are New Age shops that sell dangly things and crystals, but we don’t, we’re a quality bookshop” she said, laying her cards boldly yet politely upon the table,”We are not faddist, we have an awareness of the contents of the books.” Working at her desk, sustained by copious amounts of tea, Geraldine is an enthusiastic custodian of a wide range of esoteric discourse upon matters spiritual. “The esoteric is an endless source of fascination,” she assured me, her eyes sparkling to speak of a lifetime’s passion,“There are so many facets to the esoteric that you need never run out of things to be amazed by.”

I am ashamed to confess that even though I pass it every time I walk to the West End, I never visited the Atlantis Bookshop before because – such is the nature of my credulity – I was too scared. But thanks to Simon Costin of the Museum of British Folklore who arranged my introduction to Geraldine, I made it across the threshold eventually, and once I was in conversation with Geraldine who admits to being a witch and practising witchcraft, although she prefers the term “occultist,” I discovered my fears were rootless. However, my ears pricked up at the innocent phrase, “I’ve done some of it,” which Geraldine dropped into the middle of her sentence quite naturally and so I enquired further, curious to learn more about the nature of “it.”

“My grandmother, me and my daughter all do it. My dad did it.” she declared, as if “it” was the most common thing in the world, “I come from a family of esoterics. I was born into it, so I think it would be immoral to own a shop like this and not appreciate what people are doing. Loosely it could be called witchcraft, but in reality it is a certain perception or background intuition.”

“Our subject has become very fashionable and young academics don’t have a bloody clue, which is very frustrating for us.” she continued, rolling her eyes at the inanity of humanity,“We try to disabuse people of the myths about witches, they are good kind people on the whole. Most witches are as mortgage-bound and dog-walking as everyone else. Most witches do healing, and buy toilet paper. And there is this side of trying to commune with nature and be aware of the cycle of change. It’s a very rich and rewarding way of life. I practise a bit of magic – there’s so much you can’t learn from books and you have to do it yourself.”

With her waist-length grey hair, deep eyes, and amusingly authoritative rhetorical style, Geraldine is an engaging woman of magnanimous spirit. And I cannot deny a certain vicarious excitement on my part, brightening an overcast morning to discover myself seated in this elegant empty bookshop in Bloomsbury in conversation with a genuine witch. Yet I was still curious about the nature of “it.” So I asked again.

“Witchcraft is a very benign religion, where you work around the seasons of the year,” explained Geraldine patiently, in a pleasant measured tone, “You start off in darkness, and, in Mid-Summer, the Holly King and the Corn King have a fight and the Holly King wins and then the light begins to decline. At Yule, they fight again and the Corn King wins and the light begins to come back to the world. In agrarian societies, people got up at dawn and worked until dusk, and they adjusted how they lived by the seasons. It was the Christians who gave us the devil and we don’t know what to do with him. We have a horned god who is the god of positive male energy – not a devil at all, but the poor soul has been demonized over the years.”

Geraldine convinced me that esoteric cultures from the ancient world remain vibrant, by reminding me that witches were always “green,” ahead of their time in ecological awareness, and – although she could not disclose names – by revealing that top celebrities, from princes to pop-stars, have always frequented the Atlantis Bookshop. “We make a play of only giving out the names of our famous dead customers,” she confided to me with a tantalising smirk. “Most of our customers are practitioners – witchcraft has become the default teenage rebellion religion today,” she added with an ambivalent grin, confirming that, in spite of everything, the future looks bright for witches.

The British Museum awaits at the end of the street

Geraldine and her sister Tish outside the bookshop in the nineteen-seventies – “Those were the days when the Rolling Stones and the Beatles used to come in.”

You may also like to read about

Upon The Nature Of Gothic Horror

I believe I was born with a medieval imagination. It is the only way I can explain the explicit gothic terrors of my childhood. Even lying in my cradle, I recall observing the monstrous face that emerged from the ceiling lampshade once the light was turned out. This all-seeing creature, peering at me from above, grew more pervasive as years passed, occupying the shadows at the edges of my vision and assuming more concrete manifestations. An unexpected sound in my dark room revealed its presence, causing me to lie still and hold my breath, as if through my petrified silence I could avert the attention of the devil leaning over my bedside.

When I first became aware of gargoyles carved upon churches and illustrated in manuscripts, I recognised these creatures from my own imagination and I made my own paintings of these scaled, clawed, horned, winged beasts, which were as familiar as animals in the natural world. I interpreted any indeterminate sound or movement from the dark as indicating their physical presence in my temporal existence. Consequently, darkness, shadow and gloom were an inescapable source of fear to me on account of the nameless threat they harboured, always lurking there just waiting to pounce. At this time of year, when the dusk glimmers earlier in the day, their power grew as if these creatures of the shades might overrun the earth.

Nothing could have persuaded me to walk into a dark house alone. One teenage summer, I looked after an old cottage while the residents were on their holiday and, returning after work at night, I had to walk a long road that led through a deep wood without street lighting. As I wheeled my bicycle up the steep hill among the trees in dread, it seemed to me they were alive with monsters and any movement of the branches confirmed their teeming presence.

Yet I discovered a love of ghost stories and collected anthologies of tales of the supernatural, which I accepted as real because they extended and explained the uncanny notions of my own imagination. In an attempt to normalise my fears, I made a study of mythical beasts and learnt to distinguish between a griffin and a wyvern. When I discovered the paintings of Hieronymous Bosch and Pieter Breughel, I grew fascinated and strangely reassured that they had seen the apocalyptic visions which haunted the recesses of my own mind.

I made the mistake of going to see Ridley Scott’s The Alien alone and experienced ninety minutes transfixed with terror, unable to move, because – unlike the characters in the drama – I was already familiar with this beast who had been pursuing me my whole life. In retrospect, I recognise the equivocal nature of this experience, because I also sought a screening of The Exorcist with similar results. Perhaps I sought consolation in having my worst fears realised, even if I regretted it too?

Once, walking through a side street at night, I peered into the window of an empty printshop and leapt six feet back when a dark figure rose up from among the machines to confront my face in the glass. My companions found this reaction to my own shadow highly amusing and it was a troubling reminder of the degree to which I was at the mercy of these irrational fears even as an adult.

I woke in the night sometimes, shaking with fear and convinced there were venomous snakes in the foot of my bed. The only solution was to unmake the bed and remake it again before I could climb back in. Imagine my surprise when I visited the aquarium in Berlin and decided to explore the upper floor where I was confronted with glass cases of live tropical snakes. Even as I sprinted away down the street, I felt the need to keep a distance from cars in case a serpent might be lurking underneath. This particular terror reached its nadir when I was walking in the Pyrenees, and stood to bathe beneath a waterfall and cool myself on a hot day. A green snake of several feet in length fell wriggling from above, hit me, bounced off into the pool and swam away, leaving me frozen in shock.

Somewhere all these fears dissolved. I do not know where or when exactly. I no longer read ghost stories or watch horror films and equally I do not seek out dark places or reptile houses. None of these things have purchase upon my psyche or even hold any interest anymore. Those scaly beasts have retreated from the world. For me, the shadows are not inhabited by the spectral and the unfathomable darkness is empty.

Bereavement entered my life and it dispelled these fears which haunted me for so long. My mother and father who used to turn out the light and leave me to sleep in my childhood room at the mercy of medieval phantasms are gone, and I have to live in the knowledge that they can no longer protect me. Once I witnessed the moment of death with my own eyes, it held no mystery for me. The demons became redundant and fled. Now they have lost their power over me, I miss them – or rather, perhaps, I miss the person I used to be – yet I am happy to live a life without supernatural agency.

Fourteenth century carvings from St Katherine’s Chapel, Limehouse

You might also like to read about

The Wallpaper Of Spitalfields

One house in Fournier St has wallpapers dating from 1690 until 1960. This oldest piece of wallpaper was already thirty years old when it was pasted onto the walls of the new house built by joiner William Taylor in 1721, providing evidence – as if it were ever needed – that people have always prized beautiful old things.

John Nicolson, the current owner of the house, keeps his treasured collection of wallpaper preserved between layers of tissue in chronological order, revealing both the history and tastes of his predecessors. First, there were the wealthy Huguenot silk weavers who lived in the house until they left for Scotland in the nineteenth century, when it was subdivided as rented dwellings for Jewish people fleeing the pogroms in Eastern Europe. Yet, as well as illustrating the precise social history of this location in Spitalfields, the wider significance of the collection is that it tells the story of English wallpaper – through examples from a single house.

When John Nicolson bought it in 1995, the house had been uninhabited since the nineteen thirties, becoming a Jewish tailoring workshop and then an Asian sweatshop before reaching the low point of dereliction, repossessed and rotting. John undertook a ten year renovation programme, moving into the attic and then colonising the rooms as they became habitable, one by one. Behind layers of cladding applied to the walls, the original fabric of the house was uncovered and John ensured that no materials left the building, removing nothing that predated 1970. A leaky roof had destroyed the plaster which came off the walls as he uncovered them, but John painstakingly salvaged all the fragments of wallpaper and all the curios lost by the previous inhabitants between the floorboards too.

“I wanted it to look like a three hundred year old house that had been lovingly cared for and aged gracefully over three centuries,” said John, outlining his ambition for the endeavour, “- but it had been trashed, so the challenge was to avoid either the falsification of history or a slavish recreation of one particular era.” The house had undergone two earlier renovations, to update the style of the panelling in the seventeen-eighties and to add a shopfront in the eighteen-twenties. John chose to restore the facade as a domestic frontage, but elsewhere his work has been that of careful repair to create a home that retains its modest domesticity and humane proportions, appreciating the qualities that make these Spitalfields houses distinctive.

The ancient wallpaper fragments are as delicate as butterfly wings now, but each one was once a backdrop to life as it was played out through the ages in this tottering old house. I can envisage the seventeenth century wallpaper with its golden lozenges framing dog roses would have gleamed by candlelight and brightened a dark drawing room through the winter months with its images of summer flowers, and I can also imagine the warm glow of the brown-hued Victorian designs under gaslight in the tiny rented rooms, a century later within the same house. When I think of the countless hours I have spent staring at the wallpaper in my time, I can only wonder at the number of day dreams that were once projected upon these three centuries of wallpaper.

Flowers and foliage are the constant motifs throughout all these papers, confirming that the popular fashion for floral designs on the wall has extended for over three hundred years already. Sometimes the flowers are sparser, sometimes more stylised but, in general, I think we may surmise that, when it comes to choosing wallpaper, people like to surround themselves with flowers. Wallpaper offers an opportunity to inhabit an everlasting bower, a garden that never fades or requires maintenance. And maybe a pattern of flowers is more forgiving than a geometric design? When it comes to concealing the damp patches, or where the baby vomited, or where the mistress threw the wine glass at the wall, floral is the perfect English compromise of the bucolic and the practical.

Two surprises in this collection of wallpaper contradict the assumed history of Spitalfields. One is a specimen from 1895 that has been traced through the Victoria & Albert Museum archive and discovered to be very expensive – sixpence a yard, equivalent to week’s salary – entirely at odds with the assumption that these rented rooms were inhabited exclusively by the poor at that time. It seems that then, as now, there were those prepared to scrimp for the sake of enjoying exorbitant wallpaper. The other surprise is a modernist Scandinavian design by Eliel Saarinen from the nineteen twenties – we shall never know how this got there. John Nicolson likes to think that people who appreciate good design have always recognised the beauty of these exemplary old houses in Fournier St, which would account for the presence of both the expensive 1895 paper and the Saarinen pattern from 1920, and I see no reason to discount this theory.

I leave you to take a look at this selection of fragments from John’s archive and imagine for yourself the human dramas witnessed by these humble wallpapers of Fournier St.

Fragments from the seventeen-twenties

Hand-painted wallpaper from the seventeen-eighties

Printed wallpaper from the seventeen-eighties

Eighteen-twenties

Eighteen-forties

Mid-nineteenth century fake wood panelling wallpaper, as papered over real wooden panelling

Wallpaper by William Morris, 1880

Expensive wallpaper at sixpence a yard from 1885

1895

Late nineteenth century, in a lugubrious Arts & Crafts style

A frieze dating from 1900

In an Art Nouveau style c. 1900

Modernist design by Finnish designer Eliel Saarinen from the nineteen-twenties

Nineteen-sixties floral

Vinyl wallpaper from the nineteen-sixties

Items that John Nicolson found under the floorboards of his eighteenth-century house in Fournier St, including a wedding ring, pipes, buttons, coins, cotton reels, spinning tops, marbles, broken china and children’s toys. Note the child’s leather boot, the pair of jacks found under the front step, and the blue bottle of poison complete with syringe discovered in a sealed-up medicine cupboard which had been papered over. Horseshoes were found hidden throughout the fabric of the house to bring good luck, and the jacks and child’s shoe may also have been placed there for similar reasons.

In The Charnel House

I wonder if those who work in the corporate financial industries in Bishop’s Sq today ever cast their eyes down to the cavernous medieval Charnel House of c. 1320 beneath their feet, once used to store the dis-articulated bones of many thousands of those who died here of the Great Famine in the fourteenth century.

Inspector of Ancient Monuments, Jane Siddell, believes starving people flooded into London from Essex seeking food after successive crop failures and reached the Priory of St Mary Spital where they died of hunger and were buried here. It was a dark vision of apocalyptic proportions on such a bright day, yet I held it in in mind as we descended beneath the contemporary building to the stone chapel below.

At first, you notice the knapped flints set into the wall as a decorative device, like those at Southwark Cathedral and St Bartholomew the Great. London does not have its own stone and Jane pointed out the different varieties within the masonry and their origins, indicating that this building was a sophisticated and expensive piece of construction subsidised by wealthy benefactors. A line of small windows admitted light and air to the Charnel House below, and low walls that contain them survive which would once have extended up to the full height of the chapel.

When you stand down in the cool of the Charnel House, several metres below modern ground level, and survey the neatly-faced stone walls and the finely-carved buttresses, it is not difficult to complete the vault over your head and imagine the chapel above. Behind you are the footings of the steps that led down and there is an immediate sense of familiarity conveyed by the human proportion and architectural detailing, as if you had just descended the staircase into it.

This entire space would once have been packed with bones, in particular skulls and leg bones – which we recognise in the symbol of the skull & crossbones – the essential parts to be preserved so that the dead might be able to walk and talk when they were resurrected on Judgement Day. Yet they were rudely expelled and disposed of piecemeal at the Reformation when the Priory of St Mary Spital was dissolved in 1540.

Brick work and the remains of a beaten earth floor indicate that the Charnel House may have become a storeroom and basement kitchen for a dwelling above in the sixteenth century. Later, it was filled with rubble from the Fire of London and levelled-off as houses were built across Spitalfields in the eighteenth century. Thus the Charnel House lay forgotten and undisturbed as a rare survival of fourteenth century architecture, until 1999 when it was unexpectedly discovered by the builders constructing the current office block. Yet it might have been lost then if the developers had not – showing unexpected grace – reconfigured their building in order to let it stand.

Around the site lie stray pieces of masonry individually marked by the masons – essential if they were to receive the correct payment from their labours. Thus our oldest building bears witness to the human paradox of economic reality, which has always co-existed uneasily with a belief in the spiritual world, since it was a yearning for redemption in the afterlife that inspired the benefactors who paid for this chapel in Spitalfields more than seven centuries ago

The exterior walls are decorated with knapped flints, faced in Kentish Ragstone upon a base of Caen Stone with use of green Reigate Stone for corner stones

Window bricked up in the sixteenth century

Inside the Charnel House once packed with bones

Twelfth century denticulated Romanesque buttress brought from an earlier building and installed in the Charnel House c.1320 – traces of red and black paint were discovered upon this.

Fine facing stonework within the Charnel House

Fourteenth century masons’ marks

The Charnel House is to be seen in the foreground of this illustration from the fifteen-fifties

The Charnel House during excavations

You may also like to read about

Terry Smith, Envelope Cutter

Today we celebrate Terry Smith who cut the beautiful handmade envelopes donated by Baddeley Brothers for our Spitalfields Life 2022 calendar in support of Spitalfields City Farm

CLICK HERE TO ORDER YOUR SPITALFIELDS CITY FARM CALENDAR FOR £10

There is not much that Terry Smith does not know about envelopes. He has been cutting them for sixty years at Baddeley Brothers, the longest-established family firm of fine stationery manufacturers in London. “When I tell people I make envelopes, sometimes they look at you and ask, ‘What does it take to make envelopes?’ Terry revealed to me with a knowing smile, “So I tell them to get hold of a piece of paper and a knife and a ruler, and try to cut out the shape – because that is the trade of envelope making.”

Envelopes, especially of the brown manila variety, are mostly mundane objects that people prefer not to think about too much. But, at Baddeley Brothers, they make the envelopes of luxury and the envelopes of pleasure, envelopes with gilt crests embossed upon the flap, envelopes with enticing windows to peer through and envelopes lined with deep-coloured tissue – envelopes to lose yourself in. This is envelope-making as an art form, and Terry Smith is the supreme master of it.

Did you know there are only four types of envelope in the world? Thanks to Terry, the morning post will never be the same as I shall be categorising my mail according to styles of envelope. Firstly, there is the Diamond Shape, made from a diamond-shaped template and in which all four points meet in the middle – once this is opened, it cannot be resealed. Secondly, there is the “T” Style, which is the same as the Diamond Shape, only the lower flap ends in a straight edge rather than a point – permitting the top flap to be tucked underneath, which means the envelope can be reused. Thirdly, there is the Wallet, which is a rectangular envelope that opens on the long side. And lastly, the Pocket – which is a rectangular envelope that opens upon the short side.

“The skill of it is to make all the points meet in the middle,” confided Terry, speaking of the Diamond Shape, and I nodded in unthinking agreement – because by then I was already enraptured by the intriguing world of bespoke envelope-making.

“I was born in Shoreditch, and my mother and father were both born in Hackney. My dad was a telephone operator until the war and then he became a chauffeur afterwards. My first job, after I left school at fifteen, was at a carton maker but I was only there for three or four weeks when a friend came along and said to me, would I like to work in a ladies clothing warehouse? And I did that for a year until it got a bit iffy. The Employment Exchange sent me along to Baddeley Brothers and I joined when I was seventeen, and stayed ever since.

The company was in Tabernacle St then and I worked in the warehouse alongside the envelope cutters. It was a good thing because as somebody left another one joined and I worked with them, and I picked stuff up. Eventually when one left, they said to me, ‘Do you think you can do it?’ And I said, ‘Oh yes, give me a try.’ At first, I did the easy ones, punching out envelopes, and then I started to learn how to make the patterns and got into bespoke envelopes.

It is something that I should like to pass on myself, but I have not found anyone that can handle the paper. Once you have got the paper under the guillotine, it can be hard to get just the shape you want. And it can be quite difficult, because if the stack shifts beneath the pattern it can be very tricky to get it straight again. After you have trimmed the paper in the guillotine, then you put it in the adjustable press, and set up your pattern to cut through the paper and give you the exact shape of the envelope. I design all the patterns and, if we need a new knife, I design the shape and make the pattern myself. All of this can be done on a computer – the trade is dying, but this firm is thriving because we do bespoke. If a customer comes to us, I will always make a sample and nine times out of ten we get the job. You won’t find many people like me, because there’s not many left who know how to make bespoke envelopes.

I retired at sixty-five after I trained somebody up, but two months later I got the phone call saying, ‘Will you please come back?’ That was two years ago nearly and I was pleased to come back because I was getting a bit bored. It’s a great pleasure producing envelopes, because I can do work that others would struggle with. There’s a lot of pressure put upon you, you’ve got a couple of machines waiting and a few ladies making up the finished envelopes.

I was brought up with sport and I ran for London, I am a good all-rounder. I am a swimming instructor with disabled people at Ironmonger’s Row Baths. Every morning, I do press ups and sit ups to keep in shape – a good hour’s work out. I know that when I come into work, I’m ready to go. I’m probably fitter than most of the people here.

They’ve asked me how long can I go on making envelopes and I answer, ‘As long as I am able and as long as I am needed.'”

Terry at work making envelopes in 1990 in Boundary St

Terry sets a knife to cut the final shape of a stack of envelopes

Die cutting, 1990

Checking the quality of foiling, 1990

Alan Reeves and envelope machine, 1990

Die press proofing, 1990

Folding envelopes by hand, 1990

Proofing Press, 1990

Baddeley Brothers at Boundary St in the building that is now the Boundary Hotel, 1990

Colour photographs copyright © Estate of Colin O’Brien

Black & white photographs copyright © Baddeley Brothers

You may also like to read about

At Newmans Stationery

Today we celebrate the wonderful Newmans Stationery in Bethnal Green who printed our Spitalfields Life 2022 calendar in support of Spitalfields City Farm

CLICK HERE TO ORDER YOUR SPITALFIELDS CITY FARM CALENDAR FOR £10

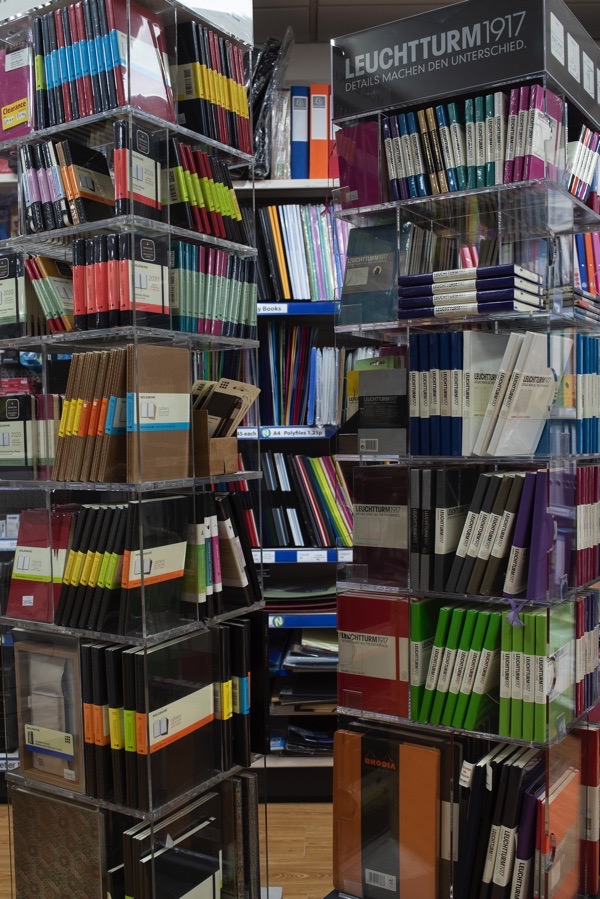

Qusai & Hafiz Jafferji

Barely a week passes without at least one visit to Newmans Stationery, a magnificent shop in Bethnal Green devoted to pristine displays of more pens, envelopes, folders and notebooks than you ever dreamed of. All writers love stationery and this place is an irresistible destination whenever I need to stock up on paper products. With more than five thousand items in stock, if you – like me – are a connoisseur of writing implements and all the attendant sundries then you can easily lose yourself in here. This is where I come for digital printing, permitting me the pleasure of browsing the aisles while the hi-tech copiers whirr and buzz as they fulfil their appointed tasks.

Swapping the murky January streets for the brightly-lit colourful universe of Newmans Stationers, Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I went along to meet the Jafferjis and learn more about their cherished family business – simply as an excuse to spend more time within the hallowed walls of this heartwarming East End institution.

We thought we would never leave when we were shown the mysterious and labyrinthine cellar beneath, which serves as the stock room, crammed with even more stationery than the shop above. Yet proprietor Hafiz Jafferji and his son Qusai managed to tempt us out of it with the offer of a cup of tea in the innermost sanctum, the tiny office at the rear of the shop which serves as the headquarters of their personal empire of paper, pens and printing. Here Hafiz regaled us with his epic story.

“I bought this business in October 1996, prior to that I worked in printing for fifteen years. It was well paid and I was quite happy, but my father and my family had been in business and that was my goal too. I am originally from Tanzania and I was born in Zanzibar where most of my relatives have small businesses selling hardware.

I began my career as a typesetter, working for a cousin of mine in Highgate, then I studied for a year at London College of Printing in Elephant & Castle. My father told me to start up a business running a Post Office in Cambridge in partnership with another cousin. They sold a little bit of stationery so I thought it was a good idea but my mind was always in printing. Every single day, I came back after working behind the counter in Cambridge to work at printing in Highgate, before returning to Cambridge at maybe one or two in the morning. I did that for almost two years, but then I said, ‘I’m not really enjoying this’ and decided to come back to London and work full time with my cousin in Highgate again.

I wondered, ‘Shall I go back to Tanzania where my dad is and start a business there or just carry on here?’ After I paid off my mortgage on my tiny flat, I left the print works and I was doing part time jobs and working a hotel but I thought, ‘Let’s try the army!’ Yet by the time I got to the third interview, I managed to find a job working for a printer in Crouch End. Then I had my mother pushing me to get married. ‘You’ve got a flat and you’ve got a job,’ she said but I could not even afford basic amenities in my house. If I wanted to eat something nice, I had to go to aunt’s house.

I realised I needed a decent job and I joined a printing firm in the Farringdon Rd as a colour planner, joining a team of four planners. Although I had learnt a lot from my previous jobs, I was not one of the most experienced workers there and I found that the others chaps would not teach me because I was the only Asian in the workforce. I used to do my work and watch the others with one eye, so I could pick up what they were doing and get better. I think I was a bit slow and so, for a long time, I would sign out and carry on working after hours to show that I was fulfilling my duties.

We did a lot of printing at short notice for the City and my boss always needed people to stay on and work late. Sometimes he would ring me at midnight and ask. ‘Hafiz, a plate has gone down, can you come in and redo it?’ I always used to do that, I never said ‘No.’

After five years, the boss asked me to become manager but I realised that I wasn’t happy because there were communication difficulties – people would not listen to me. My colleagues did not like the fact that I never said ‘No’ to any job. So I felt uncomfortable and had to refuse the promotion. When I decided to leave they offered me 50% pay rise.

Then a friend of mine who was an accountant told me about Newmans, he said was not doing very well but it was an opportunity. We looked at the figures and it did not make sense financially, compared to what I had been earning, yet me and wife decided to give it a go anyway. It took us seven years to re-establish the business.

I am still in touch with Mr & Mrs Newman who were here in Bethnal Green twelve years before we came along in 1996. Before that, they were in Hackney Rd, trading as ‘Newmans’ Business Machinery’ selling typewriters. I remember when we started there were stacks of typewriter ribbons everywhere! Digital was coming in and typewriters were disappearing so that business was as dead as a Dodo.

It was always in my mind to go into business. My idea was simply that I would be the boss and I would have people working for me taking the money. After working fourteen hours a day for six days a week, I thought it would be easy. Of course, it was not.

We refurbished the shop and increased the range of stock. We had a local actor who played Robin Hood when we re-opened. We wanted an elephant but we had to make do with a horse. We announced that a knight on horseback was coming to our shop.

We deal directly with manufacturers so we can get better discounts and sell at competitive prices. I concentrate on local needs, the demands of people within half a mile of my shop. I go to exhibitions in Frankfurt and Dubai looking for new products and new ideas, I have become so passionate about stationery…”

Nafisa Jafferji

Marlene Harrilal

‘We wanted an elephant but we had to make do with a horse’

The original Mr Newman left his Imperial typewriter behind in 1996

Hafiz Jafferji

Qusai Jafferji quit his job in the City to join the family business

Qusai Jafferji prints a t-shirt in the recesses of the cellar

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Newmans Stationery (Retail, Wholesale & Printing), 324 Bethnal Green Rd, E2 0AG

You may also like to read about