Real Life For Children, 1819

Tickets are available for my walking tour next week

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Long before the internet and before photography, the first means of cheap mass-distribution of images was woodcuts. These appealing examples, enlarged from originals no larger than a thumbnail, are selected from a set of chapbooks, Pictures Of Real Life For Children, Printed & Sold by R.Harrild, Great Eastcheap, London. Believed to date from around 1819, the series included some Cries Of London and, in spite of the occasionally pious text, these are sympathetic and characterful portrayals of working people.

While some are intended as illustrations of professional types, such as Mr Prescription the physician, others are clearly portraits, such as the Rhubarb Seller who was also included in William Marshall Craig’s Itinerant Traders of 1804. Although we shall never know who they all were, the expressive nature of each of these lively cuts – achieved with such economy of means – leads me to suspect that many were based upon specific individuals who were recognisable to readers in London at that time.

Man with his Dancing Bear. This curious sight is frequently seen about the streets of this great city, and is far from being the most contemptible.

Mary Fairlop was always industrious, she rises with the lark to pursue her labour.

Mr Prescription, the physician, is taking the round among his patients. He is pleased to see Master Goodchild so well. By taking his physic as he ought, he is just recovered from a dangerous illness.

This is Mr Ridewell, the smart little groom, who is noted for keeping himself, his stable, and his master’s horse clean.

The Farmer.

The Milkmaid.

Hair Brooms.

Clothes Props. “Buy a Prop, a prop for your clothes.”

“Pickled Salmon, Newcastle Salmon.” Here comes Johnny Rollins, known for selling Newcastle salmon.

“Fine Yorkshire Cakes, Muffins and Crumpets.” In addition to his vocal abilities, this man has lately introduced a bell, by which means the streets are saluted every morning and afternoon with vocal and instrumental music.

“Rhubarb! Rhubarb!” This is a well-known character in our metropolis. He is a Turk as his habit bespeaks him. With his box before him, he offers his rhubarb to every passerby.

“Live Cod, dainty fresh Cod.” Much praise is due to the Fishman for his honest endeavours to obtain a livelihood. At break of day, he is seen at Billingsgate buying fish, and before noon he has been heard in most parts of the metropolis.

“Old Clothes, any shoes, hats or old Clothes.”

This is John Honeysuckle, the industrious gardener, with a myrtle in his hand, the produce of his garden. He is justly celebrated for his beautiful bowpots and nosegays all round the country.

The Nut Woman.

“Beer!” This is the publican with the nice white apron. I like this man’s beer, he keeps the Coach & Horses and his pots always look so clean.

This porter, for his industry and obliging disposition, is respected.

The Cooper is just now with adze in hand. hooping a large wine cask, which is part of a large order he has received from a merchant who trades to the East and West Indies.

The Pedlar.

The Organ Grinder.

The Watchman.

You may also like to take a look at these other sets of the Cries of London

Geoffrey Fletcher’s Pavement Pounders

William Craig Marshall’s Itinerant Traders

H.W.Petherick’s London Characters

John Thomson’s Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London

More John Player’s Cries of London

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana II

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana III

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

More of Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

Chris Georgiou, Tailor

Tickets are available for my walking tour next week

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

“I’ve worked seven days a week for forty-five years – each morning I come in about half eight and stay until seven o’clock,” tailor Chris Georgiou assured me, “If I didn’t like it, I wouldn’t do it.”

I was standing in his tiny tailoring shop situated in one of the last quiet stretches of the Kings Cross Rd. “You don’t want to retire,” Chris advised us, thinking out loud and wielding his enormous shears enthusiastically, “The bank manager round the corner retired and he’s had three heart attacks in three years and he now he takes thirty-five pills a day. He came to see me. ‘Chris, never retire!’ he said. A friend of mine, a tailor who worked from home, he retired but after a couple of years he came to see me, ‘Chris,’ he said, ‘Can I come and help you for a couple of days each week? I don’t want any money, I just need a reason to walk down the road.'”

Chris shook his head at the foolishness of the world as he resumed cutting the cloth and thus I was assured of the unlikelihood of Chris ever retiring. And why should when he has so many devoted long-term customers who appreciate his work? As I discovered, when a distinguished-looking gentleman came in clutching an armful of striped shirts that matched the one he was wearing and readily admitted I was a customer of fourteen years standing. Thus it was only a brief interview that Chris was able to grant me but, like all his work, it was perfectly tailored.

“I started out to be tailor at twelve years old, to learn this job you have to start early and you need a lot of patience to hold a needle. My mother was a very good dressmaker and she made shirts, that’s where I got it from. In Cyprus, when you finish school at twelve years old, you must choose a trade. I always liked to dress smart, so I said, ‘I’m going to be a tailor.’ I came from a poor family and I couldn’t have gone to college.

So learnt from a tailor in our village of Zodia. First, I learnt to make trousers and then I learnt to make a jacket, and then it was time to change. After that, I went to another place and said, ‘I know how to make jackets.’ I told lies and I got the job, and I started to learn the art of tailoring. Then I came here in 1968, under contract to a maker of leather wear in Farringdon Rd but, after a year, I told my boss I was going off to do tailoring. And I went to several tailors to see how they do it in England and I bought this shop from one of them in 1969, just a year after I arrived. At first, I used to get jobs from other tailors doing alterations and then I acquired my own customers. 95% of them are barristers and I have never advertised, all my customers have come through recommendations.

When I make a suit, it’s not for the customer, it’s for the people who see the suit. That’s my secret. They wear their suits in chambers and the others ask them where they get their suits. My customers come from the City. It pleases me when you do something good, satisfy your customer and they leave happy. You can’t get rich by tailoring but you can make a good living. I’ve made a lot of suits for famous people whom I’m not at liberty to mention but I can tell you I made a dinner suit for Roger Daltrey, when he got an award for charity work from George Bush, and I made a suit for Lord Mayhew. He brought two security guards who stood outside the shop. I made suits for both his sons and he asked them where they got their suits. He used to go to Savile Row but now he comes here.

I don’t go out for lunch, I eat food prepared by my wife that I bring with each day from East Finchley. She doesn’t see too much of me, that must be why my marriage has lasted forty years.”

“When I make a suit, it’s not for the customer, it’s for the people who see the suit”

“To learn this job you have to start early and you need a lot of patience to hold a needle”

“It pleases me when you do something good, satisfy your customer and they leave happy”

Photographs copyright © Estate of Colin O’Brien

Chris Georgiou, 120 Kings Cross Rd, Wc1X 9DS

You may also like to read about

The Alteration Tailors Of The East End

A Couple Of Pints With John Claridge

Tickets are available for my walking tour next week

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

THE DRINK, E14 1964

John Claridge claims he is not a drinker, but I was not entirely convinced once I saw this magnificent set of beer-soaked pictures that he lined up on the bar, exploring aspects of the culture of drinking and pubs in the East End. “I used to go along with my mum and dad, and sit outside with a cream soda and an arrowroot biscuit,” John assured me, recalling his first childhood trips to the pub,“…but they might let you have a drop of brown ale.”

Within living memory, the East End was filled with breweries and there were pubs on almost every corner. These beloved palaces of intoxication were vibrant centres for community life, tiled on the outside and panelled on the inside, and offering plentiful opportunities for refreshment and socialising. Consequently, the brewing industry thrived here for centuries, inspiring extremes of joy and grief among its customers. While Thomas Buxton of Truman, Hanbury & Buxton in Spitalfields used the proceeds of brewing to become a prime mover in the abolition of slavery, conversely William Booth was motivated by the evils of alcohol to form the Salvation Army in Whitechapel to further the cause of temperance.

“When I was fifteen, we’d go around the back and the largest one in the group would go up to the bar and get the beers,” John remembered fondly, “We used to go out every weekend, Friday, Saturday and Sunday. We’d all have our suits on and go down to the Puddings or the Beggars, the Deuragon, the Punchbowl, the Aberdeen, the Iron Bridge Tavern or the Bridge House.” Looking at these pictures makes me wish I had been there too.

Yet the culture of drinking thrives in the East End today, with hordes of young people coming every weekend from far and wide to pack the bars of Brick Lane and Shoreditch, in one non-stop extended party that lasts from Friday evening until Sunday night, and stretches from the former Truman Brewery up as far as Dalston.

Thanks to John’s sobriety, we can enjoy a photographic pub crawl through the alcoholic haze of the East End in the last century – when the entertainment was homegrown, the customers were local, smoking and dogs were permitted, and all ages mixed together for a night out. Cheers, everybody!

A SMOKE, E1 1982. – “There was a relaxed atmosphere where you could walk in and talk to anybody.”

THE CONVERSATION, E1 1982. – “Who is he speaking to?”

DARTBOARD, E17 1982. -“I used to be a darts player, just average not particularly good.”

SINGING, E1 1962. -“She’d just come out of the pub…”

THE MEETING, E14, 1982. -“You don’t know what’s going on. There’s a big flash car parked there. Are they doing a piece of business?”

SLEEP, E1 1976. – “They used to club together and get a bottle of VP wine from the off-licence, and mix it with methylated spirits.”

BEERS, E1 1964. – “This is Dickensian. You wonder who’s going to step from that door. Is it the beginning of a story?”

ROUND THE BACK, E3 1963.

DOG, E1 1963. -“Just sitting there while his master went to get another pint of beer.”

EX-ALCHOHOLIC, E1 1982. – “He lived in Booth House and seemed very content that he had pulled himself out of it.”

LIVE MUSIC, E16 1982. -“It was a cold winter’s day and raining, but I had to get this picture. Live music and dancing in a vast expanse of nothing?”

THE BEEHIVE, E14 1964. – “She never stopped giggling and laughing.”

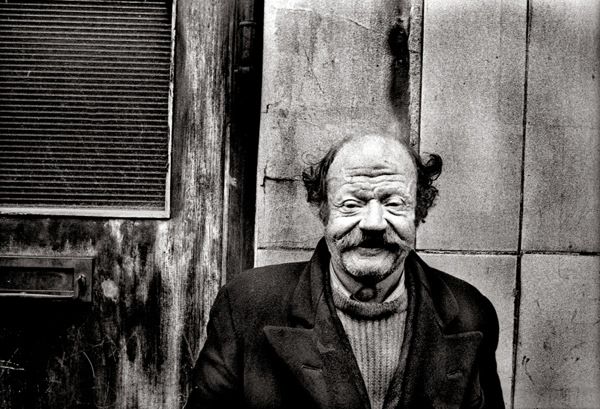

THE SMILE, E2 1962. -“He said, ‘Would you like me to smile?’ He was probably not long for this world, but he was very happy.”

IN THE BAR, E14 1964. -“I’d just got engaged to my first wife and she was one of my ex-mother-in-law’s friends. Full of life!”

THROUGH THE GLASS, E1 1982. -“I think the guy was standing at the cigarette machine.”

THE CALL, E16 1982. -“Terry Lawless’ boxing gym was above this pub. It looks as if everything is collapsing and cracking, and the shadows look like blood pouring from above.”

WHITE SWAN, E14 1982

LIGHT ALE, 1976 -“Four cans of light ale and he was completely out of it.”

CLOSED DOWN, Brick Lane 1982.

Photographs copyright © John Claridge

You may also like to take a look at

The Return Of The Gentle Author’s Writing Course

So many people have asked if I will be teaching another writing course that I have chosen to acquiesce to popular demand …

HOW TO WRITE A BLOG THAT PEOPLE WILL WANT TO READ: 12th-13th November 2022

Spend a weekend in an eighteenth century weaver’s house in Spitalfields and learn how to write a blog with The Gentle Author.

This course is suitable for writers of all levels of experience – from complete beginners to those who already have a blog and want to advance.

We will examine the essential questions which need to be addressed if you wish to write a blog that people will want to read.

“Like those writers in fourteenth century Florence who discovered the sonnet but did not quite know what to do with it, we are presented with the new literary medium of the blog – which has quickly become omnipresent, with many millions writing online. For my own part, I respect this nascent literary form by seeking to explore its own unique qualities and potential.” – The Gentle Author

COURSE STRUCTURE

1. How to find a voice – When you write, who are you writing to and what is your relationship with the reader?

2. How to find a subject – Why is it necessary to write and what do you have to tell?

3. How to find the form – What is the ideal manifestation of your material and how can a good structure give you momentum?

4. The relationship of pictures and words – Which comes first, the pictures or the words? Creating a dynamic relationship between your text and images.

5. How to write a pen portrait – Drawing on The Gentle Author’s experience, different strategies in transforming a conversation into an effective written evocation of a personality.

6. What a blog can do – A consideration of how telling stories on the internet can affect the temporal world.

SALIENT DETAILS

Courses will be held at 5 Fournier St, Spitalfields on 12th-13th November, running from 10am-5pm on Saturday and 11am-5pm on Sunday.

Lunch will be catered by Harry Thomas and tea, coffee & cakes by the Townhouse are included within the course fee of £300.

Email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com to book a place on a course.

Comments by students from courses tutored by The Gentle Author

“I highly recommend this creative, challenging and most inspiring course. The Gentle Author gave me the confidence to find my voice and just go for it!”

“Do join The Gentle Author on this Blogging Course in Spitalfields. It’s as much about learning/ appreciating Storytelling as Blogging. About developing how to write or talk to your readers in your own unique way. It’s also an opportunity to “test” your ideas in an encouraging and inspirational environment. Go and enjoy – I’d happily do it all again!”

“The Gentle Author’s writing course strikes the right balance between addressing the creative act of blogging and the practical tips needed to turn a concept into reality. During the course the participants are encouraged to share and develop their ideas in a safe yet stimulating environment. A great course for those who need that final (gentle) push!”

“I haven’t enjoyed a weekend so much for a long time. The disparate participants with different experiences and aspirations rapidly became a coherent group under The Gentle Author’s direction in a gorgeous house in Spitalfields. There was lots of encouragement, constructive criticism, laughter and very good lunches. With not a computer in sight, I found it really enjoyable to draft pieces of written work using pen and paper.Having gone with a very vague idea about what I might do I came away with a clear plan which I think will be achievable and worthwhile.”

“The Gentle Author is a master blogger and, happily for us, prepared to pass on skills. This “How to write a blog” course goes well beyond offering information about how to start blogging – it helps you to see the world in a different light, and inspires you to blog about it. You won’t find a better way to spend your time or money if you’re considering starting a blog.”

“I gladly traveled from the States to Spitalfields for the How to Write a Blog Course. The unique setting and quality of the Gentle Author’s own writing persuaded me and I was not disappointed. The weekend provided ample inspiration, like-minded fellowship, and practical steps to immediately launch a blog that one could be proud of. I’m so thankful to have attended.”

“I took part in The Gentle Author’s blogging course for a variety of reasons: I’ve followed Spitalfields Life for a long time now, and find it one of the most engaging blogs that I know; I also wanted to develop my own personal blog in a way that people will actually read, and that genuinely represents my own voice. The course was wonderful. Challenging, certainly, but I came away with new confidence that I can write in an engaging way, and to a self-imposed schedule. The setting in Fournier St was both lovely and sympathetic to the purpose of the course. A further unexpected pleasure was the variety of other bloggers who attended: each one had a very personal take on where they wanted their blogs to go, and brought with them an amazing range and depth of personal experience. “

“I found this bloggers course was a true revelation as it helped me find my own voice and gave me the courage to express my thoughts without restriction. As a result I launched my professional blog and improved my photography blog. I would highly recommend it.”

“An excellent and enjoyable weekend: informative, encouraging and challenging. The Gentle Author was generous throughout in sharing knowledge, ideas and experience and sensitively ensured we each felt equipped to start out. Thanks again for the weekend. I keep quoting you to myself.”

“My immediate impression was that I wasn’t going to feel intimidated – always a good sign on these occasions. The Gentle Author worked hard to help us to find our true voice, and the contributions from other students were useful too. Importantly, it didn’t feel like a ‘workshop’ and I left looking forward to writing my blog.”

“The Spitafields writing course was a wonderful experience all round. A truly creative teacher as informed and interesting as the blogs would suggest. An added bonus was the eclectic mix of eager students from all walks of life willing to share their passion and life stories. Bloomin’ marvellous grub too boot.”

“An entertaining and creative approach that reduces fears and expands thought”

“The weekend I spent taking your course in Spitalfields was a springboard one for me. I had identified writing a blog as something I could probably do – but actually doing it was something different! Your teaching methods were fascinating, and I learnt a lot about myself as well as gaining very constructive advice on how to write a blog. I lucked into a group of extremely interesting people in our workshop, and to be cocooned in the beautiful old Spitalfields house for a whole weekend, and plied with delicious food at lunchtime made for a weekend as enjoyable as it was satisfying. Your course made the difference between thinking about writing a blog, and actually writing it.”

“After blogging for three years, I attended The Gentle Author’s Blogging Course. What changed was my focus on specific topics, more pictures, more frequency, more fun. In the summer I wrote more than forty blogs, almost daily from my Tuscan villa on village life and I had brilliant feedback from my readers. And it was a fantastic weekend with a bunch of great people and yummy food.”

“An inspirational weekend, digging deep with lots of laughter and emotion, alongside practical insights and learning from across the group – and of course overall a delightfully gentle weekend.”

“The course was great fun and very informative, digging into the nuts and bolts of writing a blog. There was an encouraging and nurturing atmosphere that made me think that I too could learn to write a blog that people might want to read. – There’s a blurb, but of course what I really want to say is that my blog changed my life, without sounding like an idiot. The people that I met in the course were all interesting people, including yourself. So thanks for everything.”

“This is a very person-centred course. By the end of the weekend, everyone had developed their own ideas through a mix of exercises, conversation and one-to-one feedback. The beautiful Hugenot house and high-calibre food contributed to what was an inspiring and memorable weekend.”

“It was very intimate writing course that was based on the skills of writing. The Gentle Author was a superb teacher.”

“It was a surprising course that challenged and provoked the group in a beautiful supportive intimate way and I am so thankful for coming on it.”

“I did not enrol on the course because I had a blog in mind, but because I had bought TGA’s book, “Spitalfields Life”, very much admired the writing style and wanted to find out more and improve my own writing style. By the end of the course, I had a blog in mind, which was an unexpected bonus.”

“This course was what inspired me to dare to blog. Two years on, and blogging has changed the way I look at London.”

My Tenterground

“In the flesh, The Gentle Author is an even better storyteller, a magician of social history, who not only brings the past alive but reanimates the present.” Thank you to Patrick Barkham for his wonderful review of my tour in the August issue of The Oldie.

Tickets are available for my walking tour now

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

We visit TENTERGROUND as part of the tour

Ikey Jacobs in 1959

Norman Jacobs sent me this unpublished memoir written by his father Isaac (known as ‘Ikey’) Jacobs, entitled Fleish or no Fleish? Below I publish extracts from his extraordinarily detailed manuscript, comprising a tender personal testimony of a Spitalfields childhood in the years following World War I.

My Tenterground consisted of six streets in the form of a ladder, the two uprights being Shepherd St and Tenter St, and going across like four rungs. Starting at the Commercial St end were Butler St, Freeman St, Palmer St and Tilley St – and this complex was encapsulated by White’s Row, Bell Lane, Wentworth St and finally Commercial St.

Our family lived in Palmer St which had about ten houses each side. They were terraced with three floors, ground, first and top. Each floor had two rooms, the front room overlooking the street and the back room overlooking the yard. By today’s standard the rooms were small. The WC and water tap were in the yard, and there was no inside toilet or running water.

The house we lived in contained three families. On the ground floor was a tailor who used his two rooms as a workshop. He was a foreigner, or – to us – a Pullock. All foreign Jews were called Pullocks by English Jews, no matter which part of Europe they came from. It was a corruption of Pollack. Should my mother be having a few words with a Pullock, she would tell them to go back to Russia – Geography not being her strong point. Incidentally, if we had words with an English family they would tell us to go back to Palestine. So it evened itself out. Our family, with roots of settled residence in England traceable back to the seventeen-nineties, spoke no Hebrew or Yiddish worth mentioning, and I’m ashamed to say paid but only lip service to Jewish holidays.

Jack Lipschitz was the tailor’s name. He threatened me with dire consequences for mispronouncing his name – his surname of course. He had a sewing machine in his front room where his wife and daughter, Hetty, worked and a sewing machine and long bench for ironing in the back. He did all the ironing whilst his brother, Lippy – also part of the menage – worked the back room machine. In the summer, Jack did all the pressing in the yard where there was a brick fire for the irons. How these four people lived and slept there too, I don’t know.

Up one flight of stairs to a small landing saw the door to Solly Norton’s rooms, which he shared with his wife, Polly, and son, Ascher, who was about my age. They had the first gramophone I ever saw, the type with the big horn. I would often go down and play with Ascher to hear it. The Nortons kept a fruit stall in the Lane.

Up another flight, along another very small landing, the door to our front room faced you. We moved to Palmer St from Litchfield Rd in Bow where we had lived in my Aunt Betsy’s house. She was one of my mother’s elder sisters, so I assume my parents must have rented a room or two off her.

I came into the world as the second child on December 21st 1915, my sister Julia having joined the human race on on April 30th 1914. The move to Palmer St must have taken place in late 1916 or early 1917. Once there, the family increased at a steady pace – Davy 1917, Woolfy 1919, Abie 1921, Joe 1923 and Manny 1924. We were named alternatively, one on Dad’s side of the family and one on Mum’s, Julia being the name of Dad’s mum and Isaac the name of Mum’s dad.

Rebecca & John Jacobs

My father was by trade a French polisher. When there wasn’t much in that line – which was often enough – he would turn his hand to other things. He was a very good lino-layer and, as he knew quite a few furniture shops along the Whitechapel and Mile End roads, he would get the occasional job doing that. From time to time, he would act as a waiter at the Netherlands Club in Bell Lane (note the connection with the Dutch Tenterground). He did this with a tall elderly man called Phillip, and I would often boast to my friends that my father was Head Waiter at the Bell Lane Club, which is what we called it.

My mother worked as a Cigar Maker, when she was single, in a firm she referred to as Toff Levy. Like many other cigar and cigarette firms of that time, it was situated in Aldgate. It was all handwork and girls were cheap labour. Working in the same firm was a certain Sarah Jacobs, and a friendship sprang up between her and Mum. This friendship sealed my destiny for – although as yet I was unborn – Fate had decreed that I was to be a Jacobs.

My mother was christened Rebecca (but known ever after as Becky), and she was the eighth child of Isaac and Clara Levy, born in the heart of the Lane at 214 Wentworth Dwellings on November 22nd 1888, just a few months after Jack the Ripper was supposed to have written the cryptic message “The Juwes are the men who will not be blamed for nothing” on one of its walls. My Nan, who had produced this heavenly babe, was herself a midwife. But alas for poor Isaac Levy, whose forename I proudly bear, he died at the turn of the century in company with Queen Victoria. My mother had told me that she left Castle St School at thirteen years of age, which seems to coincide with the death of her Dad, who had been a lifelong cripple and had to wear, as my mother put it, a high boot.

My dad, John, first saw the light of day on March 7th 1892 at 23 Bell Lane as the first child to bless the union of David and Julia Jacobs. His arrival was followed in quick succession by that of a brother Woolf and sister Sarah, the eventual link between John and Becky when she too worked for Toff Levy.

Upon our arrival in Palmer St, a stone’s throw as the crow flies from both Wentworth Dwellings and Bell Lane, we were a family of four, but we steadily increased to nine. Living on the top floor with this ever-expanding family had its problems – getting the pushchair up and down stairs, the occasional tumble down the stairs by one of the little ones, carrying up all the water and then the disposal of the dirty water again. Sharing one WC between three families didn’t help either.

On entering our front room, on the far right wall was a small coal-fired range, grate and oven. To its right, in a sort of recess, was a bed which was occupied by Mum and Dad, and generally the latest arrival. To the left of the fireplace, was a dresser which held the plates, cups and saucers and jam jars. Cups had a high mortality rate amongst us kids, so stone jam jars were pressed into service. Most of the cups were handleless. Some of the plates were of the willow pattern design and Mum would often tell us the story they depicted – “Two little boys going to Dover” etc.

We slept in the back room. We never had pyjamas, I don’t think we’d ever heard of them. So going to bed was quite a simple procedure – jersey, trousers, boots and socks off and into bed in our shirts. I can’t remember Julie’s night attire, she slept with the younger ones. We older boys slept like sardines, heads top and bottom, with all our legs meeting in the middle.

Ikey Jacob’s Map of Dutch Tenterground

On reflection, I suppose we were a very poor family. Dad did not seem to have regular work and the burden of feeding our ever increasing family fell heavily on the shoulders of mother. In the main, we lived on fillers like bread, potatoes and rice, but it wasn’t all doom and gloom. When Dad was working we did have good meals, but memory tells me there may have been more lean times than fat ones.

Bread and marge was the usual diet for breakfast and tea. Rice boiled with shredded cabbage or currants was served for dinner many a day. Potatoes, with a knob of marge, or as chips did service another day. Fried ox heart or sausages sometimes accompanied the potatoes. Fried herrings and sprats were issued when they were plentiful and cheap. There were times we would have a tomato herring and a couple of slices of bread, William Bruce was the name on the tin of these delicacies, still a favourite of mine today.

It was a common practice in our house to buy stale bread. One of us would be sent to Funnel’s with a pillow case and sixpence to make the purchase. Early morning was the best time to go as many other families did the same thing. We were not always lucky but when we were the lady would put four or five loaves in the pillow case, various shapes and sizes, for our tanner. When we got them home mum would sort out the fresher, or shall I say the least stale, for eating, and the remainder would then be soaked down for a bread pudding. Delicious.

We would also buy cakes that way too from Ostwind’s in the Lane. Six penn’orth of stale pastries was our order to the shop assistant and she would fill a paper bag up with them, probably glad to get rid of them. When in funds, large cakes were also bought on the stale system and I would often be sent to Silver’s, high class baker in Middlesex St, to purchase a sixpenny stale bola, a large posh-looking cake.

Itchy Park was the only park in the area. Not very large, it contained the usual gravestones, seats, trees and a few swings. As boys we were not always welcomed by our elders, who would probably be trying to have a kip. I used to like picking the caterpillars, little yellow ones, off the trees and putting them in matchboxes. Someone had told me they would eventually grow into butterflies but, after watching them carefully for a few days and finding nothing had happened, I would discard them – box and all.

The park was contained by a small wall from which sprouted high railings. Along this wall, sat the homeless and down and outs. It was said the park got its name from these people rubbing their backs against the railings because they were lousy. A drinking fountain, was set in between the railings with a big, heavy metal cup secured by a heavier chain. It was operated by pressing a large metal button, and the water emerging from a round hole below it.

In front of this stood a horse trough, much needed then as most of the traffic serving Spitalfields Market was horse drawn. The Fruit & Vegetable Market was very busy, especially in the morning when Commercial St would be choked with its moving and parked traffic. All the produce would be laid out on sacks, in baskets or in boxes, and one of the sights of the market was to see porters carrying numerous round baskets of produce on their heads. For me, this was the best time of day to go looking for specks – these were bad oranges or apples thrown into a box. Selecting those with half or more salvageable, I would take them home where the bad parts were cut away and the remainder eaten.

Ikey Jacobs in 1938

There were times when Dad would have to pay the Relieving Officer a visit. I don’t know how the system worked, but if you could prove you were in need he would allocate certain items of foodstuffs, and, I suppose, a few bob. After all, the rent had to be paid. His establishment was popularly called the bun house. When Dad returned we all gathered round to inspect the contents of the pillow case as he placed them on the table. The favourite was always the jar of Hartley’s strawberry jam. Being a stone jar, when emptied, and that didn’t take long, it served as another cup. The least popular item was the cheese, suffice to say we called it ‘sweaty feet.’

Our main provider in the winter months was the soup kitchen in Butler St. It opened two or three nights a week and issued bread, marge, saveloys, sardines and of course soup. The size of the applicant’s family decided how many portions they were entitled to – the portions ran from one to four. When you first applied they issued you with a kettle, we called it a can. It had a number stamped on the side depicting how many portions you were to get. Ours had four.

When it opened for business we would all line up outside along Butler St. Once inside, six crash barriers had to be negotiated in a single line till the door leading to the serving area was reached. There would be two men doing the serving, both dressed in white and wearing tall chef’s hats. The first one would give me four loaves, always brick loaves, two packets of Van den Burgh’s Toma margarine and two tins of sardines. If I preferred saveloys to soup, he would give me eight of those. I was always told to get the soup, because we had saveloys once and they were 80% bread.

Having dealt with the grocery department, I moved along to the soup-giver. He was a great favourite of mine, known by our family as ‘the fat cook,’ a stout, domineering man with a fine beard. As I gave him the can, he would look me in the eyes and ask, “Fleish or no Fleish?” If you did not want any meat you’d say “No Fleish.” Although, as a rule, the meat was 50% fat, I was always instructed to get some. So I would look up into his eyes and reply in a loud voice “Fleish.” He would glare at me and go off to a large boiler to get it.

There was a long table with form seating down each side, set out between the boilers and the servers, where anybody, Jew or Gentile, could go in and sit down to a bowl of soup and a thick slice of bread. They did three different varieties of soup – rice, pea and barley alternatively, one variety per night. People who did not want the soup at all, but just the groceries, were given a metal disc with the portion number stamped on it. Funny, not wanting soup in a soup kitchen.

Every Passover, before they closed for the summer, we would be given four portions of groceries for the holiday. Four packets of tea and of coffee, (I loved the smell of that coffee, its aroma came right through the red packet with Hawkins printed on it) Toma marge and many other foodstuffs. But not matzos – these were obtainable from the synagogue. Dad would come back from Duke’s Place Shul with about six packets of these crunchy squares. The ones we disliked most were Latimer’s because they were hard, but generally he would bring Abrahams & Abrahams, a trifle better. But beggars can’t be choosers and I suppose we were beggars, now I come to think of it.

Eventually the time came when we were told we were to leave the Tenterground. It was going to be pulled down. All I felt was despair. I knew no other place or way of life. Those dirty streets and slum houses were part of me. Long after we left, I would dream I was back there only to wake up to the reality that the Tenterground had gone for ever. Well, not quite for ever, there is still a little boy who haunts those long vanished streets – Ikey Jacobs.

A page of Ikey Jacobs’ manuscript

You may also like to read about

At Waterbeach

“In the flesh, The Gentle Author is an even better storyteller, a magician of social history, who not only brings the past alive but reanimates the present.” Thank you to Patrick Barkham for his wonderful review of my tour in the August issue of The Oldie.

Tickets are available for my walking tour now

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

I set out to visit the intriguingly named Waterbeach and Landbeach in Cambridgeshire with the object of viewing Denny Abbey. Built in the twelfth century as an outpost of Ely Cathedral, it passed through the hands of the Benedictine Monks, the Knights Templar and a closed order of Franciscan nuns known as the ‘Poor Clares’ – all before being converted into a private home for the Countess of Pembroke in the fifteenth century. Viewed across the meadow filled with cattle, today the former abbey presents the appearance of an attractively ramshackle farmhouse.

A closer view reveals fragments of medieval stonework protruding from the walls, tell-tale signs of how this curious structure has been refashioned to suit the requirements of diverse owners through time. Yet the current mishmash delivers a charismatic architectural outcome, as a building rich in texture and idiosyncratic form. From every direction, it looks completely different and the sequence of internal spaces is as fascinating as the exterior.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the property came into the ownership of the Ministry of Works and archaeologists set to work deconstructing the structure to ascertain its history. Walking through Denny Abbey today is a vertiginous experience since the first floor spaces occupy the upper space of the nave with gothic arches thrusting towards the ceiling at unexpected angles. Most astonishing is to view successive phases of medieval remodelling, each cutting through the previous work without any of the reverence that we have for this architecture, centuries later.

An old walnut tree presides over the bleached lawn at the rear of the abbey, where lines of stone indicate the former extent of the building. A magnificent long refectory stands to the east, complete with its floor of ancient ceramic tiles. While the Farmland Museum occupies a sequence of handsome barns surrounding the abbey, boasting a fine collection of old agricultural machinery and a series of tableaux illustrating rural trades.

Nearby at Landbeach, I followed the path of a former Roman irrigation system that extends across this corner of the fen, arriving at the magnificent Tithe Barn. Stepping from the afternoon sunlight, the interior of the lofty barn appeared to recede into darkness. As my eyes adjusted, the substantial structure of purlins and rafters above became visible, arching over the worn brick threshing floor beneath. Standing in the cool shadow of a four hundred year old barn proved an ideal vantage point to view the meadow ablaze with sunlight in this exceptional summer.

Denny Abbey, Waterbeach

Mysterious stone head at Denny Abbey

The Farmland Museum, Waterbeach

Tithe Barn, Landbeach

You may also like to read my other story about Waterbeach

At The Caslon Letter Foundry

“In the flesh, The Gentle Author is an even better storyteller, a magician of social history, who not only brings the past alive but reanimates the present.” Thank you to Patrick Barkham for his wonderful review of my tour in the August issue of The Oldie.

Tickets are available for my walking tour now

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

22/23 Chiswell St with Caslon’s delivery van outside the foundry

For centuries, Caslon was the default typeface in the English language. William Caslon set up his type foundry in Chiswell St in 1737, where it operated without any significant change in the methods of production until 1937. These historic photographs taken in 1902, upon the occasion of the opening of the new Caslon factory in Hackney Wick, record both the final decades of the unchanged work of traditional type-founding, as well as the mechanisation of the process that would eventually lead to the industry being swept away by the end of the century.

The Directors’ Room with portraits of William Caslon and Elizabeth Caslon.

Sydney Caslon Smith in his office

Clerks’ office, 15th November 1902. A woman sits at her typewriter in the centre of the office.

Type store with fonts being made up in packets by women and boys working by candlelight.

Another view of the type store with women making up packets of fonts.

Another view of the type store.

Another part of the type store.

In the type store.

A boy makes up a packet of fonts in the type store.

Room of printers’ supplies including type cases, forme trolleys and electro cabinets.

Another view of the printers’ supplies store.

Printing office on an upper floor with pages of type specimens being set and printed on Albion and Imperial handpresses.

Packing department with crates labelled GER, GWR, LNWR, CALCUTTA, BOMBAY, and SYDNEY.

New Caslon Letter Foundry at Rothbury Rd, Hackney Wick, 1902.

Harold Arthur Caslon Smith at his rolltop desk in Hackney Wick with type specimens from 1780 on the wall, Friday 7th November, 1902.

Machine shop with plane, lathes and overhead belting.

Gas engines and man with oil can.

Lathes in the Machine Shop.

Hand forging in the Machine Shop.

Another view of lathes in the Machine Shop.

Type store with fonts being made up into packets.

Type matrix and mould store.

Metal store with boy hauling pigs upon a trolley.

Casting Shop, with women breaking off excess metal and rubbing the type at the window.

Another view of the Casting Shop.

Another view of the Casting Shop.

Founting Shop, with women breaking up the type and a man dressing the type.

Casting metal furniture.

Boys at work in the Brass Rule Shop.

Boys making packets of fonts in the Despatch Shop, with delivery van waiting outside the door.

Machine shop on the top floor with a fly-press in the bottom left.

Woodwork Shop.

Brass Rule Shop, hand-planing the rules.

Caretaker’s cottage with caretaker’s wife and the factory cat.

Photographs courtesy St Bride Printing Library

You may also like to read about

William Caslon, Letter Founder