Roy Wild, Hop Picker

Next tickets available for my walking tour on Sunday 21st August

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

There is Roy standing on the right with his left hand stuck in his pocket – to indicate the appropriate air of nonchalance befitting a street-wise man of the world of around twelve years old – on a hopping expedition with his family from Hoxton.

Roy went hop picking each year with this relations until he reached the age of eighteen and, at this season, he always recalls his days in Kent. Still in touch with many of those who were there with him in the hop fields in the fifties, Roy was more than happy to get out his photographs and settle down with a cup of tea with a drop of whisky in it, and tell me all about it.

“I first went hopping with my family in 1948 when I was ten or eleven. We went to Selling near Faversham in Kent. The fields were owned by Alan Bruce Neame of Shepherd Neame, and he would employ people to pick the hops which he sold to breweries. We all lined up on the last day and he would pay each of us in person.

Some Londoners went by train from London Bridge St, all waiting on the station and carrying all their stuff with them. We were very fortunate, dad’s brother Ernie, he had an asphalt company and had an open backed lorry, for which he made a frame for a rain canopy, and we all went down to hopping together – our family, Ernie’s family, also Renee’s sister Mary and her family. Ernie would drive down to Hoxton and pick us up at Northport St, with all our bits and pieces, our bags and suitcases with bed linen and that type of thing, and away we’d all go down to Faversham. We’d go at the weekend, so we could spend a day unpacking and be ready to start picking on Monday.

There was us hop pickers from London but Neame would also employ ‘home-dwellers,’ these were Kentish people. The accommodation they lived in was far superior to what we were subjected to. We were given no more than Nissen huts, square huts made of corrugated iron with a door and that was about all, no windows. It was very, very primitive. We washed in a bowl of water and the toilet was a hole dug in a field. My mother would take old palliasses down with us from Hoxton and they would be stuffed with straw or hay from the barn, and that would our mattresses. The beds were made of planks, very basic and supported upon four logs to prop them up off the floor. You’d put the palliasses on top of the planks and the blankets on top of that. The huts were always running alive with creepy-crawlies, so anyone that had a phobia of that wasn’t really suited to hop picking.

There was another room next to it which was half the size, this was our kitchen. My dad would take down an old primus stove for cooking. It was fuelled by paraffin and the more you pumped it up the fiercer the flame, the quicker the cooking. It was only a small thing that sat on a box. The alternative to that was cooking outside. The farmer would provide bundles of twigs known as ‘faggots,’ to fuel the fire and we would rig up a few bricks with a grill where we’d put the kettle and a frying pan. They’d literally get pot-black in the smoke.

We usually went from three weeks to a month hop picking, sometimes the whole of September, and you could stay on for fruit picking. When we first started, we picked into a big long troughs of sacking hanging down inside a wooden frame. They were replaced by six bushel baskets. The tally man would come round with a cart to collect the six bushel baskets and mark your card with how much you had picked, before carrying the hops away to the oasthouses for drying.

At the time, we were paid one shilling and sixpence a bushel. You’d pick into a bushel basket while you were sitting with it between your legs and when it was full, you’d walk over to the six bushel basket and tip it in. My dad was a fast picker, he’d say ‘Come on Roy, do it a bit quicker!’ All your fingers got stained black by the the hops, we called it ‘hoppy hands.’

If you had children with you, they would mess about. Their parents would be rebuking them and telling them to get picking because the more you picked, the more you earned. Some people could get hold of a bine, pull the leaves off and, in one sweep, take all the hops off into the basket. Other people, to bulk up their baskets would put all kinds of things in there. they would put the bines at the bottom of the six bushel basket and nobody would know, but if you got caught then you was in trouble. My dad showed me how to fill a six bushel basket up to the five bushel level and then put your arms down inside to lift up the hops to the top just before the tally man came round.

The adults were dedicated pickers because you had to buy food all the time and being there could cost more money than you made. There was a little store near us called ‘Clinges’ and further up, just past the graveyard, was another store which was more modern called ‘Blythes’, and next door to that was a pub called the ‘White Swan’ and that was the release for all the hop pickers. They all used to go there on Saturday and Sunday nights and there’d be sing-songs and dancing, before going back to work on Monday morning. It was the only enjoyment you had down there, except – if you didn’t go up to the pub – you’d get all the familes sitting round of a weekend and reminiscing and singing songs, round a big open fire made up of the faggots

We worked from nine o’clock until about four, Monday to Friday. The owner of the hop fields employed guys to work for him who were called ‘Pole Pullers,’ they had big long poles with a sharp knife on the end and when you pulled a bine, if it didn’t come down, you’d call out for a pole puller and with his big long pole he’d cut the top of it and the rest if it would fall down. When it was nearing four o’clock, they’d call out ‘Pull no more bines!’ which was what all the kids were waiting for because by this time they’d all had just about enough. A hop field can be one muddy place and if you’re in among all that with wellingtons on it can get pretty sticky. If it was ready to rain, the pole pullers would also go round and call ‘Pull no more bines.’ Nobody was expected to work outside in the rain. We dreaded the rain but we welcomed the pole pullers when they called out, because that was the day’s work done until the following morning.

We looked forward to going hop picking because it was the chance of an adventure in the country. It was just after the war and we’d had it rough in Hoxton. I was born in 1937 and I’d grown up through the war, and we still had ration books for a long time afterwards. I was a young man in the fabulous fifties and the swinging sixties. In the fifties, we had American music and Elvis Presley, and in the sixties the Beatles and British music. Hop picking was being mechanised, they had invented machines that could do it. So we grew away from it, and young men and young women had better things to do with their time.”

Roy stands in the centre of this family group

Renee Wild and Rosie Wild

Picking into a six bushel basket

Roy’s father Andy Wild rides in the cart with his brother Ernie

Roy’s grandfather Andrew Wild is on the far left of this photo

Roy is on the far right of this group

Roy sits in the left in the front of this picture

Rosie, Mary & Renee

Roy’s father Andy Wild with Roy’s mother Rosie at the washing up and Pearl

Roy’s mother, Rosie Wild

Renee, Mary & Pearl

Roy’s father Andy stands on the left and his Uncle Ernie on the right

Roy

Roy (with Trixie) and Tony sit beside their mother Rosie

Roy’s mother and father with his younger brother Tony

Roy stands on the right of this group of his pals

You may also like to read about

Hopping Portraits

Next tickets available for my walking tour are on Sunday 21st August

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

When Tower Hamlets Community Housing staged a Hop Picking Festival down in Cable St, affording the hop pickers of yesteryear a chance to gather and share their tales of past adventures down in Kent, Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I went along to join the party.

Connie Aedo – “I’m from Shovel Alley, Twine Court, at the Tower Bridge end of Cable St. I was very little when I first went hop picking. At weekends, when we worked half-days, my mum would let me go fishing. Even after I left school, I still went hop picking. Friends had cars and we drove down for the weekend, as you can see in the photo. Do you see the mirrors on the outside of the sheds? That’s because men can’t shave in the dark!”

Derek Protheroe, Terry Line, Charlie Protheroe, Connie Aedo and Terry Gardiner outside the huts at Jack Thompsett’s Farm, Fowle Hall, near Paddock Wood, 1967

Maggie Gardiner – “My mum took us all down to Kent for fruit picking and hop picking. Once, parachutes came down in the hop gardens and we didn’t know if they were ours or not, but they were Germans. So my mum told me and the others to go back to the hut and put the stew on. On the way back, a German aeroplane flew over and machine gunned us and we hid in a ditch until the man in the pub came to get us out. My mum used to say, ‘If you can fill an umbrella with hops, I’ll get you a bike,’ but I’m still waiting for it. We had some good times though and some laughs.”

Alifie Rains (centre) and Johnny Raines (right) from Parnham St, Limehouse, in the hop gardens at Jack Thompsett’s Farm, Fowle Hall, Kent

Vera Galley – “I was first taken hop picking as a baby. My mum, my nan and my brothers and sisters, we all went hop picking together. I never liked the smell of hops when I was working in the hop gardens because I had to put up with it, but now I love it because it brings back memories. ”

Mr & Mrs Gallagher with Kitty Adams and Jackie Gallgher froom Westport St, Stepney, in the hop gardens at Pembles Farm, Five Oak Green, Kent in 1950

Harry Mayhead – “I went hop picking when I was nine years old in 1935 and it was easy for kids. It was like going on holiday, getting a break from the city for a month. Where I lived in a block of flats and the only outlook was another block of flats, you never saw any green grass.”

Mr & Mrs Gallagher with their grandchildren at Pembles Farm, 1958

Lilian Penfold – ” I first went hop picking as a baby. I was born in August and by September I was down there in the hop garden. M daughter Julie, she was born in July and I took her down her down in September too. We were hopping until ten years ago when then brought in the machines and they didn’t need us any more. My aunt had grey hair but it turned green from the hops!”

The Liddiard family from Stepney in Kent, 1930

Dolly Frost – ” I was a babe in arms when they took me down to the hop gardens and I went picking for years and years until I was a teenager. I loved it while was I was growing up. My mother used to say, ‘Make sure you pick enough so you can have a coat and hat,’ and I got a red coat and matching red velour hat. As you can see, I like red.”

The Gallagher family from Stepney outside their huts at Pembles Farm, 1952

Charles Brownlow – “I started hop picking when I was seven. It was a working holiday to make some money. This was during the bombing, you woke up and the street had gone overnight, so to get to the country was an escape. You wouldn’t believe how many people crammed into those tiny huts. You took a jug of tea to work with you and at first it was hot but then it went cold but you carried on drinking it because you were hot. You could taste the hops in your sandwiches because it was all over your hands. There was a lot of camaraderie, people had nothing but it didn’t matter.”

Mr & Mrs Gallagher from Stepney at Pembles Farm

Margie Locke – “I’m eighty-eight and I went hop picking and fruit picking from the age of four months, and I only packed up last year because the farm I where went hop picking has been sold for development and they are building houses on it.”

At Highwood’s Farm, Collier St, Kent

Michael Tyrell – “I was first taken hop picking in the sixties when I was five months old, and I carried on until 1981 when hops was replaced by rapeseed which was subsidised by the European Community. In the past, one family was put in a single hut, eleven feet by eleven feet, but we had three joined together – with a bedroom, a kitchen with a cooker run off a calor gas bottle and even a television run off a car battery. There was still no running water and we had to use oil lamps. My family went to Thompsett’s Farm about three miles from Paddock Wood from the First World War onwards. I have a place there now, about a mile from where my grandad went hop picking. The huts are still there and we scattered my uncle’s ashes there.”

Annie & Bill Thomas near Cranbrook, Kent

Lilian Peat (also known as ‘Splinter’) – “My mum and dad and seven brothers and three sisters, we all went hop picking from Bethnal Green every year. I loved it, it was freedom and fresh air but we had to work. My mum used to get the tail end of the bine and, if we didn’t pick enough, she whipped us with it. My brothers used to go rabbiting with ferrets. The ferrets stayed in the hut with us and they stank. And every day we had rabbit stew, and I’ve never been able to eat rabbit since. We were high as kites all the time because the hop is related to the cannabis plant, that’s why we remember the happy times.”

John Doree, Alice Thomas, Celia Doree and Mavis Doree, near Cranbrook, Kent

Mary Flanagan – “I’m the hop queen. I twine the bines. I first went hop picking in 1940. My dad sent us down to Plog’s Hall Farm on the Isle of Grain. We went in April or May and my mum did the twining. Then we did fruit picking, then hop picking, then the cherries and bramleys until October. We had a Mission Hall down there, run by Miss Whitby, a church lady who showed us films of Jesus projected onto a sheet but, if the planes flew overhead, we ran back to our mothers. We used to hide from the school inspector, who caught us eventually and put us in Capel School when I was eight or ten – that’s why I’m such a dunce!”

Annie & Bill Thomas with Roy & Alf Baker, near Cranbrook, Kent

Portraits copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Archive photographs courtesy of Tower Hamlets Community Housing

You may also like to take a look at

Hopping Photographs

Next tickets available for my walking tour are on Sunday 21st August

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

This selection of hop picking photographs is from the archive of Tower Hamlets Community Housing. Traditionally, this was the time when East Enders headed down to the Hop Farms of Kent & Sussex, embracing the opportunity of a breath of country air and earning a few bob too.

Bill Brownlow, Margie Brownlow, Terry Brownlow & Kate Milchard, with Keith Brownlow & Kevin Locke in front, at Guinness’ Northland’s Farm at Bodiam, Sussex, in 1958. Guinness bought land at Bodiam in 1905 and eight hundred acres were devoted to hop growing at its peak.

Julie Mason, Ted Hart, Edward Hart & friends at Hoathleys Farm, Hook Green, near Lamberhurst, Kent

Lou Osbourn, Derek Protheroe & Kate Day at Goudhurst Farm

Margie Brownlow & Charlie Brownlow with Keith Brownlow, Kate Milchard & Terry Brownlow in front at Guinness’ Northland’s Farm at Bodiam, Sussex, in 1950

Mr & Mrs Gallagher with Kitty Adams & Jackie Gallagher from Westport St, Stepney, in the hop gardens at Pembles Farm, Five Oak Green, Kent in 1959

Jackie Harrop, Joan Day & George Rogers at Whitbread’s Farm, Beltring, Kent in 1949

Mag Day (on the left at the back) in the hop gardens with others at Highwood’s Farm, Collier St, in 1938

Pop Harrop at Whitbread’s Farm, Beltring, Kent in 1949

Sarah Watt, Mrs Hopkins, Steven Allen, Ann Allen, Tom, Albert Allen & Sally Watt in the hop gardens at Jack Thompsett’s Den Farm, Collier St, Kent in 1943

Harry Watt, Tom Shuffle, Mary Shuffle, Sally Watt, Julie Callagher, Ada Watt & Sarah Watt in the hop gardens at Jack Thompsett’s Den Farm, Collier St, Kent in the fifties

Harry Watt, Sally Watt, Sarah Watt holding Terry Ellames in the hop gardens at Jack Thompsett’s Den Farm, Collier St, Kent in 1957

Harry Ayres, a pole puller, in the hop gardens at Diamond Place Farm, Nettlestead, Kent

Emmie Rist, Theresa Webber, Kit Webber & Eileen Ayres in the hop gardens at Diamond Place Farm, Nettlestead, Kent

Kit Webber with her Aunt Mary, her Dad Sam Webber and her Mum, Emmie Ris,t in the hop gardens at Diamond Place Farm, Nettlestead, Kent

Harry Ayres with his wife Kit Webber in the hop gardens at Diamond Place Farm, Nettlestead, Kent.

Richard Pyburn, Mag Day, Patty Seach and Kitty Gray from Kirks Place, Limehouse, in the hop gardens at Highwoods Farm, Collier St, Kent

The Gorst and Webber families at Jack Thompsett’s Farm, Fowle Hall, Kent in the forties

Kitty Waters with sons Terry & John outside the huts at Pembles Farm, Five Oak Green, Kent in 1952

Mr & Mrs Gallagher from Westport St, Stepney, with their grandchildren in the hop gardens at Pembles Farm, Five Oak Green, Kent in 1958

Sybil Ogden, Doris Cossey, Danny Tyrrell & Sally Hawes near Yalding, Kent

John Doree, Alice Thomas, Celia Doree & Mavis Doree in the hop gardens near Cranbrook, Kent

Bill Thomas & his wife Annie, in the hop gardens near Cranbrook, Kent

The Castleman Family from Poplar hop picking in the twenties

Terry & Margie Brownlow at Guinness’ Northland’s Farm at Bodiam in Sussex in 1949

Alfie Raines, Johnny Raines, Charlie Cushway, Les Benjamin & Tommy Webber in the Hop Gardens at Jack Thompsett’s Farm at Fowl Hall near Paddock Wood in Kent

Lal Outram, Wag Outram & Mary Day on the common at Jack Thompsett’s Farm at Fowl Hall near Paddock Wood in Kent in 1955

Taken in September 1958 at Moat Farm, Five Oak Green, Kent. Sitting on the bin is Miss Whitby with Patrick Mahoney, young John Mahoney and Sheila Tarling (now Mahoney) – Sheila & Patrick were picking to save up for their engagement party in October

Maryann Lowry’s Nan, Maggie ,on the left with her Great-Grandmother, Maryann, in the check shirt in the hop gardens, c.1910

Having a rest in hop gardens at Whitbread’s Farm, Beltring, Kent in 1966. In the back row are Mary Brownlow, Sean Locke, Linda Locke, Kate Milchard, Chris Locke & Margie Brownlow with Kevin Locke and Terry Locke in front.

Margie Brownlow & her Mum Kate Milchard at Whitbreads Farm in Beltring, Kent in 1967. These huts were two stories high. The children playing outside are – Timmy Kaylor, Chrissy Locke, Terry Locke, Sean Locke, Linda Locke & Kevin Locke.

Chris Locke, Sally Brownlow, Linda Brownlow, Kate Milchard, Margie Brownlow, Terry Locke & Mary Brownlow at Whitbread’s Farm, Beltring, Kent in 1962

Johnno Mahoney, Superintendant of the Caretakers on the Bancroft Estate in Stepney, driving the “Mahoney Special” at Five Oak Green in 1947

The Clarkson family in the hop gardens in Staplehurst. Gladys Clarkson , Edith Clarkson, William Clarkson, Rose Clarkson & Henry Norris.

John Moore, Ross, Janet Ambler, Maureen Irish & Dennis Mortimer in 1950 at Luck’s Farm, East Peckham, Kent

Kate Fairclough, Mrs Callaghan, Mary Fairclough & Iris Fairclough at Moat Farm, Five Oak Green, Kent in 1972

A gang of Hoppers from Wapping outside the brick huts at Stilstead Farm, Tonbridge, Kent with Jim Tuck & John James in the back. In the middle row the first person on the left is unknown, but the others are Rose Tuck, holding Terry Tuck, Rose Tuck, Danny Tuck & Nell Jenkins. In the front are Alan Jenkins, Brian Tuck, Pat Tuck, Jean Tuck, Terry Taylor & Brian Taylor.

Nanny Barnes, Harriet Hefflin, “Minie” Mahoney & Patsy Mahoney at Ploggs Hall Farm

In the Hop Gardens at Jack Thompsett’s Farm at Fowl Hall, near Paddock Wood in Kent in the late forties. Alfie Raines, Edie Cooper, Margie Gorst & Lizzie Raines

The Day family from Kirks Place, Limehouse, at Highwoods Farm in Collier St, Kent in the fifties

Annie Smith, Bill Daniels, Pearl Brown & Nell Daniels waiting for the measurer in the Hop Garden at Hoathley’s Farm, Hook Green, Kent

On the common outside the huts at at Hoathley’s Farm, Hook Green, Kent – you can see the oasthouses in the distance. Rita Daniels, Colleen Brown, Maureen Brown, Marie Brown, Billy Daniels, Gerald Brown & Teddy Hart , with Sylvie Mason & Pearlie Brown standing.

The Outram family from Arbour Sq outside their huts at Hubbles Farm, Hunton, Kent. Unusually these were detached huts but, like all the others, they made of corrugated tin and all had one small window – simply basic rooms, roughly eleven feet square

Janis Randall being held by her mother Joyce Lee andalongside her is her father, Alfred Lee in a hop garden, near Faversham in September 1950

David & Vivian Lee sitting on a log on the common outside Nissen huts used to house hop pickers

Gerald Brown, Billy Daniels & Dennis Woodham in the hop gardens at Gatehouse Farm near Brenchley, Kent, in the fifties

Nelly Jones from St Paul’s Way with Eileen Mahoney, and in the background is Eileen’s mum, “Minie” Mahoney. Taken in the fifties in the Hop Gardens at Ploggs Hall Farm, between Paddock Wood and Five Oak Green.

At Jack Thompsett’s Farm at Fowl Hall, near Paddock Wood in Kent

Ploggs Hall Farm Ladies Football Team. Back Row – Fred Archer, Lil Callaghan, Harriet Jones, Unknown, Unknown, Nanny Barnes, Liz Weeks, Harriet Hefflin, Johnno Mahoney. Front Row – Doris Hurst Eileen Mahoney & Nellie Jones

John Moore, Ross, Janet Ambler, Maureen Irish & Dennis Mortimer in 1950 at Luck’s Farm, East Peckham, Kent

The Outram and Pyburn families outside a Kent pub in 1957, showing clockwise Kitty Tyrrell, Mary Pyburn, Charlie Protheroe, Rene Protheroe, Wag Outram, Derek Protheroe in the pram, Annie Lazel, Tom Pyburn, Bill Dignum & Nancy Wright.

Sally Watt’s Hop Picker’s account book from Jack Thompsett’s Den Farm, Collier St, Kent in the fifties

Tony Hall, Photographer

Next tickets available for my walking tour are on Sunday 21st August

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Bonner St, Bethnal Green

Tony Hall (1936-2008) would not have described himself as a photographer – his life’s work was that of a graphic designer, political cartoonist and illustrator. Yet, on the basis of the legacy of around a thousand photographs that he took, he was unquestionably a photographer, blessed with a natural empathy for his subjects and possessing a bold aesthetic sensibility too.

Tony’s wife Libby Hall, known as a collector of dog photography, revisited her husband’s photographs before giving them to the Bishopsgate Institute where they are held in the archive permanently. “It was an extraordinary experience because there were many that I had never seen before and I wanted to ask him about them.” Libby confessed to me, “I noticed Tony reflected in the glass of J.Barker, the butcher’s shop, and then to my surprise I saw myself standing next to him.”

“I was often with him but, from the mid-sixties to the early seventies, he worked shifts and wandered around taking photographs on weekday afternoons,” she reflected, “He loved roaming in the East End and photographing it.”

Born in Ealing, Tony Hall studied painting at the Royal College of Art under Ruskin Spear. But although he quickly acquired a reputation as a talented portrait painter, he chose to reject the medium, deciding that he did not want to create pictures which could only be afforded by the wealthy, turning his abilities instead towards graphic works that could be mass-produced for a wider audience.

Originally from New York, Libby met Tony when she went to work at a printers in Cowcross St, Clerkenwell, where he was employed as a graphic artist. “The boss was member of the Communist Party yet he resented it when we tried to start a union and he was always running out of money to pay our wages, giving us ‘subs’ bit by bit.” she recalled with fond indignation, “I was supposed to manage the office and type things, but the place was such a mess that the typewriter was on top of a filing cabinet and they expected me to type standing up. There were twelve of us working there and we did mail order catalogues. Tony and the others used to compete to see who could get the most appalling designs into the catalogues.”

“Then Tony went to work for the Evening News as a newspaper artist on Fleet St and I joined the Morning Star as a press photographer.” Libby continued,” I remember he refused to draw a graphic of a black man as a mugger and, when the High Wizard of the Klu Klux Klan came to London, Tony draw a little ice cream badge onto his uniform on the photograph and it was published!” After the Evening News, Tony worked at The Sun until the move to Wapping, using this opportunity of short shifts to develop his career as a graphic artist by drawing weekly cartoons for the Labour Herald.

This was the moment when Tony also had the time to pursue his photography, recording an affectionate chronicle of the daily life of the East End where he lived from 1960 until the end of his life – first in Barbauld Rd, Stoke Newington, then in Nevill Rd above a butchers shop, before making a home with Libby in 1967 at Ickburgh Rd, Clapton. “It is the England I first loved …” Libby confided, surveying Tony’s pictures that record his tender personal vision for perpetuity,”… the smell of tobacco, wet tweed and coal fires.”

“He’d say to me sometimes, ‘I must do something with those photographs,'” Libby told me, which makes it a special delight to publish Tony Hall’s pictures.

Children with their bonfire for Guy Fawkes

In the Hackney Rd

“I love the way these women are looking at Tony in this picture, they’re looking at him with such trust – it’s the way he’s made them feel. He would have been in his early thirties then.”

On the Regent’s Canal near Grove Rd

On Globe Rd

In Old Montague St

In Old Montague St

In Club Row Market

On the Roman Rd

In Ridley Rd Market

In Ridley Rd Market

In Artillery Lane, Spitalfields

Tony & Libby Hall in Cheshire St

Tony & Libby Hall in Cheshire St

Photographs copyright © Libby Hall

Images Courtesy of the Tony Hall Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute

Libby Hall & I would be delighted if any readers can assist in identifying the locations and subjects of Tony Hall’s photographs.

You may also like to read

Whistler In The East End

Next tickets available for my walking tour are on Sunday 21st August

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

William Jones, Limeburner, Wapping High St

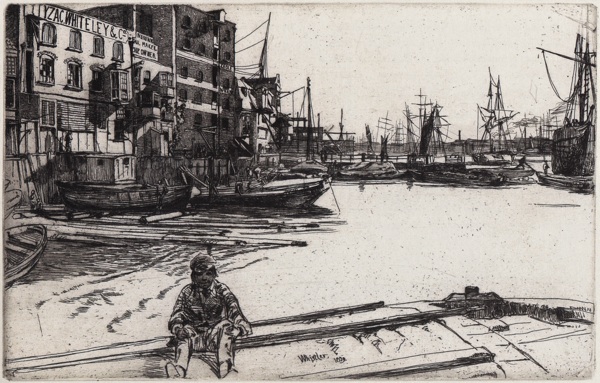

American-born artist, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, was the first artist to appreciate the utilitarian environment of the East End on its own terms, seeing the beauty in it and recognising the intimate relationship of the working people to the urban landscape they had constructed.

He was only twenty-five when he arrived in London from Paris in the summer of 1859 and, rejecting the opportunity of staying with his half-sister in Sloane St, he took up lodgings in Wapping instead. Influenced by Charles Baudelaire to pursue subjects from modern life and seek beauty among the working people of the teeming city, Whistler lived among the longshoremen, dockers, watermen and lightermen who inhabited the riverside, frequenting the pubs where they ate and drank.

The revelatory etchings that he created at this time, capturing an entire lost world of ramshackle wooden wharfs, jetties, warehouses, docks and yards. Rowing back and forth, the young artist spent weeks in August and September of 1859 upon the Thames capturing the minutiae of the riverside scene within expansive compositions, often featuring distinctive portraits of the men who worked there in the foreground.

The print of the Limeburner’s yard above frames a deep perspective looking from Wapping High St to the Thames, through a sequence of sheds and lean-tos with a light-filled yard between. A man in a cap and waistcoat with lapels stands in the pool of sunshine beside a large sieve while another figure sits in shadow beyond, outlined by the light upon the river. Such an intriguing combination of characters within an authentically-rendered dramatic environment evokes the writing of Charles Dickens, Whistler’s contemporary who shared an equal fascination with this riverside world east of the Tower.

Whistler was to make London his home, living for many years beside the Thames in Chelsea, and the river proved to be an enduring source of inspiration throughout a long career of aesthetic experimentation in painting and print-making. Yet these copper-plate etchings executed during his first months in the city remain my favourites among all his works. Each time I have returned to them over the years, they startle me with their clarity of vision, breathtaking quality of line and keen attention to modest detail.

Limehouse and The Grapes – the curved river frontage can be recognised today

The Pool of London

Eagle Wharf, Wapping

Billingsgate Market

Longshore Men

Thames Police, Wapping

Black Lion Wharf, Wapping

Looking towards Wapping from the Angel Inn, Bermondsey

You may also like to read about

Dickens in Shadwell & Limehouse

Madge Darby, Historian of Wapping

Ricardo Cinalli, Artist

Tickets are available for my walking tour now

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Portrait by Lucinda Douglas Menzies

When artist Ricardo Cinalli graduated from the University of Rosario in Argentina, a mentor offered to introduce him to Salvador Dali, if Ricardo was prepared to travel to London. In 1973, travelling by boat across the Atlantic to Barcelona in anticipation of encountering his hero, Ricardo was unfortunately delayed by two whole weeks and when he arrived in London, Dali was gone – but instead he discovered a whole new life.

At a party, Ricardo met Eric Elstob who was buying a house in Fournier St, opening the door to a surreal world of an entirely different nature. “We came to Spitalfields on a very depressing day. My God, it was a dump! I said to Eric, ‘Are you crazy?’ It was overwhelming – the market, the rats, the prostitutes and the meths drinkers outside the house. And the minute he opened the door I could see the place was in a horrible condition. But Eric explained to me to the history of the Huguenots, and the bells in the church rang and suddenly I understood the magic. He said to me, ‘You are invited to join my life’s project to restore this house.’ I had nothing to lose, so I said ‘Yes.’ He was a brave man to want to come and live here when no-one was interested. We had no money, we did all the work ourselves.”

Sitting comfortably in a green leather chair rescued from the Market Cafe, Ricardo spoke lyrically about his memorable introduction to Spitalfields, now these Herculean labours are safely in the past. It was an era when an imaginative few first recognised the beauty in the neglected houses and set about restoring them by their own labours, as Ricardo and Eric did at 14 Fournier St, taking seven years to bring it to conclusion.“It was a very exciting time, but for a person like myself it was very difficult, because I wasn’t used to this kind of dereliction, I was brought up in a house with ceilings and floors. We restored these houses with our own hands. Gilbert & George next door, they restored the panels one by one personally. To me it was unthinkable that I could do that, I was a painter, an artist. I came from a petit bourgeois background where you get someone else to do it. Yet I really had a fantastic time – it was horrible sometimes but there were moments of great joy too. And in the process I learnt something of the history of old London.”

After pausing to collect his thoughts silently,“I did that,” said Ricardo philosophically, gesturing towards Fournier St,” and then I did this,” he continued, referring to the house in Puma Court where he lives today. “And then I said, ‘Enough is enough!'”, he added, adopting the understated heroic tone of a Roman emperor reflecting on past victories, a role that suits his gracious nature and venerable Latin features perfectly.

Until this week, I only knew Ricardo Cinalli from his portrait on one of Simon Pettet’s tiles at Dennis Severs’ House, so I was exhilarated to walk into his five metre by five metre cube studio, dug into the ground beneath his narrow old house in Puma Court, complete with a glass pyramid ceiling looking up towards the lofty spire of Christ Church, Spitalfields. With supreme politesse, Ricardo opened the panel set into the floor of the studio to show me all the proud artefacts he found in the construction of his studio, which are preserved there.

As he dug down, Ricardo realised he was excavating a rubbish dump, with broken ceramics stretching from the sixteenth to the nineteeth century, innumerable oyster shells and clay pipes, rollers used by men in the eighteenth century to curl their wigs and even a pot of perfume with an address in Paris – once belonging to one of those Huguenot weavers that Eric Elstob first told Ricardo about, so many years before.

Working in his Spitalfields studio, Ricardo creates spirited and passionate paintings that are Baroque in their emotionalism and Surrealist in their imaginative extravagance. Over a career spanning more than forty years, he has become internationally renowned for his works on canvas, his huge pastel drawings, his theatre designs and his murals which include a vast fresco in a cathedral in Umbria and now his magnum opus – more than five years in the making – a giant fresco covering all the walls of a custom-built edifice in Punta del Este in Uruguay. An Argentinian of Italian descent, with his modest manners and ambitious paintings, Ricardo convincingly incarnates the spirit of his Renaissance predecessors in the art of fresco.

Ricardo led me from his minimalist studio into the tiny old house balanced on top of it. We ascended a narrow staircase with trompe l’oeil panelling into a living room lined with wooden panelling rescued from the former synagogue in Fournier St. Each floor comprises just one room and on the next storey is Ricardo’s bedroom and bathroom, all in one space, with every surface painted with classical designs. Finally, we reached the kitchen under the eaves with windows on both sides – like the foc’sle of a ship – allowing us exciting views in both directions over the roofscape of Spitalfields.

As we drank our tea quietly, gazing up from the kitchen window to the spire that overshadows the house, Ricardo told me the story of how his cat “Dolce” went missing when he was living in Fournier St, while the church was being renovated. One still moonlit night, Ricardo heard a distant “miaow” coming from on high. Cats will always climb upwards, and Dolce was found at last, stuck at the top of the spire.

“Spitalfields has some magic element, don’t you think?” Ricardo proposed delicately with a sympathetic smile, casting his deep brown eyes contemplatively upwards to Hawksmoor’s bizarre edifice looming over us. Seeing it through Ricardo’s eyes, from his sunlit painted kitchen, at the top of this narrow house, perched above his extraordinary cube studio with the pyramid on the roof, it was only natural to agree.

Ricardo Cinalli never met Salvador Dali but he found his own magic instead, here in Spitalfields.

In Ricardo Cinalli’s giant mural-in-progress in Uruguay, entitled “Humanistic Homage to the Millennium,” the figures are eight metres high. Click on this image to enlarge.

The glass pyramid on the roof of Ricardo Cinalli’s Spitalfields studio.

Banana boxes that are souvenirs of the seven years Ricardo spent restoring 14 Fournier St.

Finds discovered while digging the hole for the studio. Note the eighteenth century clay curlers for men’s wigs and the Huguenot perfume pot from Paris.

Looking towards Fournier St from the rear of Puma Court.

Watermen’s Stairs

Tickets are available for my tour from next Saturday

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Wapping Old Stairs

I need to keep reminding myself of the river. Rarely a week goes by without some purpose to go down there but, if no such reason occurs, I often take a walk simply to pay my respects to the Thames. Even as you descend from the Highway into Wapping, you sense a change of atmosphere when you enter the former marshlands that remain susceptible to fog and mist on winter mornings. Yet the river does not declare itself at first, on account of the long wall of old warehouses that line the shore, blocking the view of the water from Wapping High St.

The feeling here is like being offstage in a great theatre and walking in the shadowy wing space while the bright lights and main events take place nearby. Fortunately, there are alleys leading between the tall warehouses which deliver you to the waterfront staircases where you may gaze upon the vast spectacle of the Thames, like an interloper in the backstage peeping round the scenery at the action. There is a compelling magnetism drawing you down these dark passages, without ever knowing precisely what you will find, since the water level rises and falls by seven metres every day – you may equally discover waves lapping at the foot of the stairs or you may descend onto an expansive beach.

These were once Watermen’s Stairs, where passengers might get picked up or dropped off, seeking transport across or along the Thames. Just as taxi drivers of contemporary London learn the Knowledge, Watermen once knew the all the names and order of the hundreds of stairs that lined the banks of the Thames, of which only a handful survive today.

Arriving in Wapping by crossing the bridge in Old Gravel Lane, I come first to the Prospect of Whitby where a narrow passage to the right leads to Pelican Stairs. Centuries ago, the Prospect was known as the Pelican, giving its name to the stairs which have retained their name irrespective of the changing identity of the pub. These worn stone steps connect to a slippery wooden stair leading to wide beach at low tide where you may enjoy impressive views towards the Isle of Dogs.

West of here is New Crane Stairs and then, at the side of Wapping Station, another passage leads you to Wapping Dock Stairs. Further down the High St, opposite the entrance to Brewhouse Lane, is a passageway leading to a fiercely-guarded pier, known as King Henry’s Stairs – though John Roque’s map of 1746 labels this as the notorious Execution Dock Stairs. Continue west and round the side of the river police station, you discover Wapping Police Stairs in a strategic state of disrepair and beyond, in the park, is Wapping New Stairs.

It is a curious pilgrimage, but when you visit each of these stairs you are visiting another time – when these were the main entry and exit points into Wapping. The highlight is undoubtedly Wapping Old Stairs with its magnificently weathered stone staircase abutting the Town of Ramsgate and offering magnificent views to Tower Bridge from the beach. If you are walking further towards the Tower, Aldermans’ Stairs is worth venturing at low tide when a fragment of ancient stone causeway is revealed, permitting passengers to embark and disembark from vessels without wading through Thames mud.

Pelican Stairs

Pelican Stairs at night

View into the Prospect of Whitby from Pelican Stairs

New Crane Stairs

Wapping Dock Stairs

Execution Dock Stairs, now known as King Henry’s Stairs

Entrance to Wapping Police Stairs

Wapping Police Stairs

Metropolitan Police Service Warning: These stairs are unsafe!

Wapping New Stairs with Rotherithe Church in the distance

Light in Wapping High St

Wapping Pier Head

Entrance to Wapping Old Stairs

Wapping Old Stairs

Passageway to Wapping Old Stairs at night

Aldermans’ Stairs, St Katharine’s Way

You may also like to read about

Madge Darby, Historian of Wapping