Marc Gooderham, Painter

Later Afternoon, Fournier St, Spitalfields

There are so many art galleries in my neck of the woods that I have adopted the Jean-Luc Godard approach to visiting them. In other words, I take it at a run just as Anna Karina, Sami Rey and Claude Brasseur sprinted through the Louvre in “Band à Part.” Yet very occasionally – as I am nipping in and out of every gallery in Redchurch St on the first Thursday of the month – something will stop me in my tracks and cause me to linger. Such was the case when I first came upon the visionary paintings of Marc Gooderham.

Here was the world – the very streets – that I knew, but subtly transformed as if by memory or dream. Marc chooses places that exist in the periphery of vision and recreates them in his mind’s eye, revealing the otherness of the familiar with understated surrealism.

It was this shock of recognition that first halted me in front of his pictures, pausing to establish the locations and then becoming seduced by the brooding melancholy of these deserted streets, absent of pedestrians yet haunted by the presence of all those who have come through. With some of these places, I thought only I had spotted their unlikely appeal – because, like Marc, I am drawn to the shabby poetry of these disreputable and neglected corners, sites that characterise the distinctive identity of London more truthfully than the homogeneous sheen of all the gleaming corporate palaces.

“This project started from exploring the city and wandering the streets, so I know it will be an endless undertaking because there’s always something new to discover around every corner,” Marc admitted to me with a helpless smile, as we trudged the empty streets around Petticoat Lane one morning recently. “What makes this such a fascinating place is the proximity of the City of London to these old terraces – and the contrast of the street art makes it even more interesting.” he continued, raising his eyes to the boarded up, tumbledown buildings. “I try to avoid catching the bus,” he confessed as we crossed Commercial St, “so I get the chance to walk and discover the next site for a painting. Once I find the site, I take lots of photographs and make sketches, looking for the best time of day.”

Starting with a pencil sketch to establish the perspective, Marc builds up his paintings in washes of acrylic upon canvas. At first he paints the sky, then the architecture and finally the accretions upon the surface of the buildings. He calls these, the three key elements to a painting – elements that combine in a moment circumscribed by the fleeting light. It is a moment set against the age of the buildings and the ephemeral street art which can change overnight.

When Marc and I visited some of his locations, I was fascinated to discover he had rearranged them in his pictures, removing lampposts and reconfiguring the proportions to create his desired effect. Just as these sites do not draw attention to themselves, Marc’s paintings are quiet works that withhold their painterly and conceptual sophistication behind a superficial veil of heightened realism.

A softly-spoken man with gentle intense eyes, Marc works three days of every week at a job to pay the bills and spends the rest of his time devoted to his paintings which each take six weeks from conception to completion. For the last two years, Marc has been working on this epic series of paintings of lonely corners, assembling a set that he plans eventually to show as a gazetteer of his personal vision of London. Or, as Marc put it plainly, “Two years ago, I devoted my life to painting.”

Inspired by L.S. Lowry and Edward Hopper, Marc Gooderham’s cityscapes beneath a Northern sky possess a soulfulness and mystery that hint at undisclosed life behind those doors and windows. They are well-worn settings for the enigmatic human drama of the city, comprising more stories than you can ever know.

Together Again, Redchurch St.

Vallance Rd, Whitechapel

Fallen, Hanbury St.

Rio Cinema, Dalston.

The Tyger, Great Eastern St.

Corner of The Street, Redchurch St.

The Lonely Stretch, Coronet St.

Back To The Old House, Princelet St.

Marc Gooderham

Paintings copyright © Marc Gooderham

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana II

Already – I am reliably informed – the police are clearing homeless people from the Whitechapel Rd in advance of 2012 when this route will be transformed into the Olympic Mile. Meanwhile, the imminent opening of a new shopping centre made of sea containers, selling lifestyle brands to young professionals at the junction of Bethnal Green Rd and Norton Folgate, presages a rough time for the fly-pitchers who gather at this spot each Sunday morning to trade a few possessions on the pavement in the hope of earning a little spare cash.

When John Thomas Smith published his Vagabondiana in 1815, he included “remarkable beggars and itinerant traders and others persons of notoriety” and even two centuries later it appears that all manner of street people are treated with equal contempt. Yet there is an irony to Smith’s title because, in his unsentimental portraits, the street hawkers retain their self possession and dignity, revealed as resourceful individuals striving with brave tenacity to forge a modest living.

It was a year ago I first discovered John Thomas Smith’s etchings of vagabonds in the Bishopsgate Archive and yesterday I was excited to come across a further collection from which I publish these examples. Revisiting Smith’s work, I like it even more for the sharp eye and humane sensibility employed to such magnificent effect in these finely drawn images.

Living in Spitalfields, I am constantly aware of the drama of the street traders, arriving early to set up their wares, standing all day in the cold and wearily packing away their heavy goods when everyone else has gone home. Daily, this arduous ritual continues, yet these same traders are tireless in maintaining the buoyant good spirits that are essential in market life. Even so, they are not guaranteed of an income, their livelihoods are at the mercy of the weather, the whims of the passing crowd, or – in the case of the Bethnal Green Rd fly-pitchers – the loutish market inspectors moving them on.

If there is no job and you have no money, then selling things on the street can be a way to survive and achieve self -respect too, asserting your identity as a participant in the drama of urban life. This is why I find these drawings by John Thomas Smith so touching – because he witnesses the quiet heroism of the outcast poor who recreated themselves as street sellers. Equally, it fills me with regret to see their contemporary counterparts treated so poorly. Because this lamentable state of affairs – in which the most vulnerable are exposed to the most harassment – suggests that we have not progressed very far in two hundred years.

Images from Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to see the original post

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

and read about

The Fly-Pitchers of Spitalfields

Di England, Stitches in Time

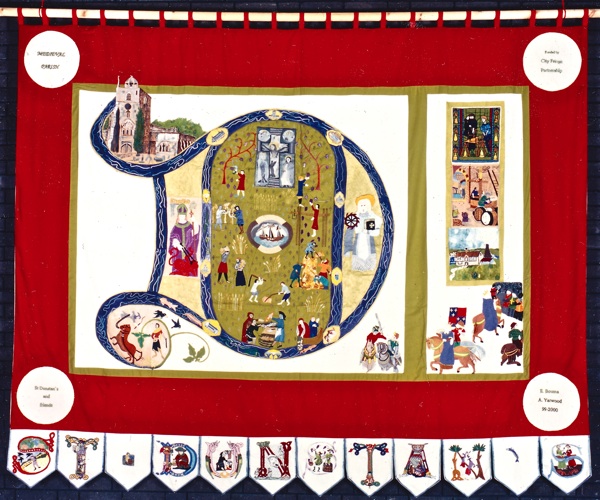

This is Di England of Stitches in Time with a tapestry based on the Roque Map of East London, 1746 – just one of hundreds of elaborate textile pieces, created collaboratively and involving over three thousand people, that she has supervised in recent years. As a consequence, the former Assembly Room of Limehouse Town Hall – in the shadow of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s St Anne’s, Limehouse – has been turned into a kind of giant sewing box where a million reels of thread and scraps of fabric are neatly organised in containers. There you can find everything you could need for the embroidery, appliqué, batik, printing, painting and weaving that is involved in the creation of these textile masterpieces which tell the story of the East End through stitching. In these works, intricate details reveal the contribution of individuals while the overall conceptions are a devised collectively, requiring critical decisions about the nature of the social pictures that result.

Inspired by the trade union banners that were once housed here when the building was a museum of Labour history, Stitches in Time has been involved with all kinds of groups across the East End to create pictorial histories of communities, devised as endeavours that serve to bring people together in the practise of making. Existing today as a social enterprise run along co-operative lines, Stitches in Time runs outreach groups alongside the business of tapestry-making. Especially important is “English for Sewing,” providing a social focus for isolated women who do not speak English, in fulfilment of the remit of Stitches in Time to bring cultures closer by getting people from different backgrounds sewing side by side. In effect, using sewing as a means of developing social cohesion, literally stitching communities together.

In a rare moment of repose, I was able to sit down with Di in a quiet corner of the Assembly Room – surrounded by piles of textiles and sewing paraphernalia – while she spoke to me of her own background and how it all started.

“I was an ordinary girl from St Albans. I had signed up for Social Anthropology because I was interested in people and instead I discovered it was all about statistics. But when I went to St Albans Arts College, I rang up my mother and said, “I found the right thing, first time.” Yet although I wanted to be an artist, I couldn’t think of a way to relate it to everyday life. We were from Yorkshire originally, but my father died when I was very young and my mother came South to earn a living. She was a primary school teacher, an educationalist with a passionate belief in the expressive arts.

I trained in painting & sculpture at the Bristol & West of England Academy and at Chelsea College of Art. At Chelsea, the textiles department was next door and I responded to that. My grandmother was a seamstress and two of my aunts were dressmakers who rode motor bikes in the nineteen thirties. Even as a child, I would collect leaves to make dyes and I gathered boxes of textiles.

I worked as a teacher at Newham in the early seventies before I joined Freeform Arts, a community arts organisation in Dalston and I found it refreshing because it was all to do with making, putting art where it wasn’t removed from everyday life. The question we asked ourselves was how could you create things that had relevance for people in their daily lives. At first, the Arts Council said, “We will fund the roses but not the dandelions.” though gradually they accepted the idea that art could be created where people lived, in the workplace and in schools, and they started a community arts panel.

Stitches in Time had its origin in 1993, I was doing a project at Beatrice Tate School in Bethnal Green, designing a mosaic, looking at the legacy of the Huguenots in the area. And I thought, “What were they doing here?” I had just finished designing a mural in Carnaby St in Soho which also had Huguenots, and I realised that both locations were gates to the city. It made me appreciate what refugees have contributed. I thought, “What can I do that everyone can participate in?”

At that time, I was setting up a print workshop in the Spitalfields Market and we made tapestries there that were a cultural history of the East End told by its people. We hung them up in the market and discovered there was huge demand for tapestries as community projects. By 1999, we received funding to create this organisation, Stitches in Time, with a special emphasis on local history. We moved into Limehouse Town Hall in 2001 and the next year we became a registered charity.

Bonnard, Chagall and Ingres were my inspirations, when I was a painter, but I have found a different way to make paintings in textiles now.”

For the millenium, Stitches in Time oversaw the creation of more than fifty tapestries that mapped out the history and culture of the East End and were exhibited in six exhibitions throughout the territory. Now Di England is looking for a sponsor for the next major project, “Tales of Trade told through Textiles” which will involve seven weeks of intensive work with different groups at ten venues and then exhibiting sixty-four textile pieces. If you can help contact Di England mail@stitchesintime.org.uk

The Tower of London by Bluegate Fields Infants School & Mothers’ Group.

St Dunstan’s by Members of St Dunstan’s Parish, Stepney.

Life Cycle of the Silk Worm by Shapla Primary School & Mothers’ Group.

The Jacquard Loom by Bancroft Women’s Group.

Jewish Wedding by Kobi Nazrul Centre.

Petticoat Lane by Heba Women’s Project.

You may also like to read these other stories about textiles

At Stephen Walters & Sons, Silkweavers

Paul Bommer & Christopher Smart & His Cat Jeoffry

Whenever I walk along Old St, I always think of the brilliant eighteenth century poet Christopher Smart, who once lived here in the St Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics with only his cat Jeoffry for solace, on the spot where the Co-operative and Argos are today. So when artist Paul Bommer asked me to suggest a subject for an illustrated print, I had no hesitation in proposing Christopher Smart’s eulogy to his cat Jeoffry, the best description of the character of a cat that I know. And, to my amazement and delight, Paul has illustrated all eighty-nine lines, each one with an apposite feline image.

In an age when only aristocrats with private incomes were able to be poets, Christopher Smart was a superlative talent who struggled to make his path through the world, and his emotional behaviour became increasingly volatile as result. With small means, he fell into debt whilst a student at Cambridge and even though his literary talent was acknowledged with awards and scholarships, his delight in high jinks and theatrical performances did not find favour with the University. Once he married Anna Maria Canaan, Smart was unable to remain at Cambridge and came to London, seeking to make ends meet in the precarious realm of Grub St. His prolific literary career turned to pamphleteering and satire, publishing hundreds of works in a desperate attempt to keep his wife and two little daughters, Marianne and Elizabeth Ann.

Eventually, he signed a contract to write a weekly magazine, The Universal Visitor, and the strain of producing this caused Smart to have a fit, sometimes ascribed as the origin of his madness. Yet there are divergent opinions as to whether he was mad at all, or whether his consignment was in some way political on the part of John Newbery, the man who was both Smart’s publisher and father-in-law. However, Smart made a religious conversion at this time, and there is an account of him approaching strangers in St James’ Park and inviting them to pray with him.

In Smart’s day, Old St was the edge of the built up city with market gardens and smallholdings beyond. The maps of St Luke’s Hospital show gardens behind and it was possible that like John Clare in the Northamptonshire Lunatic Asylum, Smart was simply left alone to tend the garden and get on with his writing. Consigned at first on 6th May 1757 as a “curable” patient, Smart was designated “incurable” whilst there and subsequently transferred to Mr Potter’s asylum in Bethnal Green as a cheaper option. Meanwhile his wife Anna Maria took their two daughters to Ireland and he never saw them again. In 1763, Smart was released through intervention of friends and lived eight another years, imprisoned for debt in King’s Bench Walk Prison in April 1770, he died there in May 1771.

“For I Will Consider My Cat Jeoffry” was never printed in Smart’s day, it was first published in 1939 after being discovered in manuscript amongst Smart’s papers, and subsequently W.H. Auden gave a copy to Benjamin Britten who wrote a famous setting as part of a choral work entitled “Rejoice in the Lamb” in 1942.

The irony is that the “madness” of Christopher Smart, which was his unravelling as a writer in his own time, signified the creation of him as a poet who spoke beyond his age. Smart is sometimes idenitified as one of the Augustan poets, notable for their formality of style and content, but the idiosyncratic language, fresh observation and fluid form of “For I Will Consider My Cat Jeoffry” break through the poetic convention of his period and allow the poem to speak across the centuries.

It is the tender observation present in these lines that touches me most, speaking of the fascination of a cat as a source of joy for one with nothing else in the world. In fact, Smart was often known as Kit or Kitty and I wonder if he saw an image of himself in Jeoffry and it liberated him from the tyranny of his circumstance. Simply by following his nature, Jeoffry becomes holy in Christopher Smart’s eyes, exemplifying the the wonder of all creation.

It was a triumphant observation for a man who was losing his life, yet it is all the more remarkable that it is solely through this playful masterpiece he is remembered today. He did not know that, at the moment of disintegration, his words were gaining immortality thanks to the presence of his cat Jeoffry. And this is why, whenever I walk along Old St with my face turned to the wind, I cannot help thinking of poor Christopher Smart.

Christopher Smart (1722-71)

Paul Bommer at St Luke’s, Old St.

The St Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics in Old St where Christopher Smart lived with his cat Jeoffry on a site now occupied by Argos and The Co-operative.

St Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics, Old St, in the nineteenth century.

Paul Bommer in the rose garden on the site of the former St Luke’s Hospital garden where Christopher Smart’s cat Jeoffry once roamed.

Paul Bommer’s print of Christopher Smart’s “For I will consider my cat Jeoffry.”

The Gentle Author’s cat Mr Pussy.

Paul Bommer’s delft tile portrait of Mr Pussy.

Copies of Paul Bommer’s limited edition print of Christopher Smart’s “For I will consider my cat Jeoffry” are available from the Spitalfields Life online shop.

Artwork copyright © Paul Bommer

Archive image from Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

Robert Boyd-Bowman, Alexander Boyd

With the dress-sense of Cary Grant and the swagger of Captain Hook, Robert Boyd-Bowman – known universally as “Boyd” – is a familiar figure in Spitalfields. A gentleman for whom the word “dapper” might have been invented, he is also a celebrated raconteur. When you engage Boyd in conversation, you never know where it may lead, because he has lived so many lifetimes that stories simply come tumbling out of him.

You had better keep up, because Boyd is equally likely to be popping off to New York or out for a nice lunch, or taking a trip down to his tailoring workshop in Bow, or his shirt factory in Chatham, or flying to Rome to show his new tie collection. A fearless entrepreneur with impeccable manners, Boyd – the proprietor of Alexander Boyd – possesses an ebullience that has carried him through a string of professional disasters during a rollercoaster career in business. A lesser soul might have descended into cynicism, yet for Boyd these events have had the opposite effect – sharpened his resolve to discover what has true meaning for him. And the unlikely outcome is that Boyd has become a champion for the cause of making things in England, seeking ways to keep traditional skills alive in this country.

“I opened my first office in Duke St, St James at the age of nineteen, I heard that Fortnum & Mason did the best squeezed orange juice in the morning so I thought it would ideal to have an office just around the corner.

I only had one job in my life – my father and godfather got together and decided “The boy’s not very bright, so we’d better get him a job in the City.” At seventeen and a half, I was an insurance claims broker at Lloyds but after four months my line manager told me, “We don’t work like that here.” I was working too hard, but my had father told me when I started the job, “You be on time, you work as hard as you can and you leave when they let you.” It was unbelievable! At that point, I realised you can’t make money working for other people.

I grew up in Kensington in a lovely house in Warwick Gardens with a big garden, and even though we’re talking about the nineteen forties, I felt I was brought up in the Victorian era. As an only child, I had to entertain myself, so I started off with golf balls. I always broke the basement window and it was taken out of my pocket money which meant I went off to prep school with nothing each term. I needed a few quid, so I bought bits and pieces from boys that were leaving and sold them to those that were arriving. I did a bit of trading. My father got concerned because he couldn’t figure how I always had money, so he asked the headmaster to keep an eye on me, in case I was becoming a thief.

After I left the City, I found a job selling dry powder fire extinguishers. You sold on the road. I just knocked on doors. I knew I could sell anything. I was part of a team – a supervisor and five salesmen.The supervisor bought the extinguishers and sold them to the salesmen, the more you bought, the cheaper they were and the greater the commission you earned. The aim of the exercise was to get to be a supervisor, so you were taking a commission off everybody. We were selling a lot of these extinguishers, they were ideal for cars and no-one had thought of that before. It was up to the moment, until the Ministry of Defence decided to sell off a lot of these things after the war. Nobody knew if they worked until it came to use them and unfortunately these had set solid – no longer dry powder but cement! There were tragic news stories, and that was the end of the industry. You could never sell another one on the road.

Next we sold water heaters, it was a bloody brilliant idea – in the sixties there were a lot of homes that didn’t have hot water. This heater had electrodes and all you had to do was attach it to the pipe somewhere near the tap and plug it in. They sold well and the Financial Times did a fantastic article. However, the copper electrodes were expensive and the people up in Birmingham who were manufacturing them substituted something else, and they blew up. We should have been selling the fire extinguishers after the water heaters, not the other way around!

Then I went into the textile business, with a man who was a leather maker – a Frenchman. We had this factory in Rampart St in the East End and we started selling suede and leather clothing. Within a year, we had a whole building in Bond St with showrooms, offices and a cutting room on the top floor. We were doing very well and we opened another factory in the East End in Arbour Sq, and I went to Spain to buy more production – and when I came back my partner had disappeared with all the money. He was a big gambler and he lost a lot.

We had to close the place down and sell the stock, and there was this man who came in to buy it all. So I said to him, “I can sell but I don’t have any money and you have a lot of merchandise.” He agreed to let me sell it and I filled up suitcases with stuff in his warehouse in West Kensington. I didn’t have a car, so I put an advert in the evening newspaper for a chauffeur at twenty pounds a week plus expenses and I had lots of replies. They had to be in livery and have a decent car.

We packed the car with suitcases of clothes on Monday but I didn’t know if I’d be able to pay the guy on Friday – I let him put the petrol in the car. So either I had to do a runner or be able to pay him, but at the end of the first day I’d cleared enough to pay him and his petrol, and I still had four days left to run. In those days, buyers in each department of big stores bought their own stock on the shop floor and at the end of the first week I’d cleared a hundred quid, which in 1965 was equivalent to three grand today. I was back on track, although the driver turned out to be a gambler. All these people were gamblers. At the end of five years, I went back to my supplier and said I want a piece of the action, but his partner didn’t want it so that’s when I headed off on my own.

I bought an interest in a diamond manufacturer in Antwerp and became a dealer on the diamond bourse. I found it was difficult to sell anything in Europe at that time, there was the first oil crisis and the Bader Meinhoff gang. So I moved to Hong Kong which was a diamond centre but, even though it was a free port, you had to deal with states that were military juntas. I got involved in the Philippines with a client who wouldn’t pay and I had to underwrite the debt personally, and it wiped me out.

I came back to England and the only business I knew was the job stock business and fortunately I had an aunt who left me a couple of grand, and I took the money and invested in the stock market and made many thousands more. I bought dead stock in bulk from East End clothing factories and resold it. Being out in the Far East, I realised that China was going to be admitted to the World Trade Organisation and I could see that we were going to be swamped by cheap imports. A lot of clothing that had been produced in the United Kingdom was going to made offshore in future. It was already happening in the seventies.

I could see it would leave some smaller players who wanted to carry on making in England, and this was when I started getting involved with manufacturing in England to cater for retailers who I knew wanted this. The “Made in England” label has always imparted a certain gravity and I thought it would be a shame to see it go completely, as if it never happened. I realised I had to get involved in the top end of the market, because you can’t compete with China and the Far East for price. They can reproduce things, but they can’t make English shirts since ours are made by hand whereas theirs are made by machine. A shirt that is made by hand requires particular skills and it will look completely different.

Now, we’re doing better than we’ve ever done before, because the world wants products that are “Made in England.” It is an international signal of good taste. You never ask an Englishman about his tailor, his shirtmaker or where he gets his shoes made, but the rest of the world wants a label. And England is pre-eminent in the world for the quality of tailoring. The worst thing for us is that people don’t recommend us because they want to keep it a secret. Everybody else puts the label where you can see it when you open the jacket, but we sew ours inside the pocket where no-one can see it. A brand tells one story, but the clothes we make tell their own stories. In the end, you start to do things for enjoyment rather than monetary gain, it becomes about making people happy, making something for people that appreciate it.

I admit I am a gambler. If the odds are in my favour, I will always take a punt. Anyone that tells you they have never made a mistake is lying – without mistakes, there’s no life.”

“the dress-sense of Cary Grant and the swagger of Captain Hook..”

Robert Boyd-Bowman outside his tailoring shop in Artillery Passage

You may also like to read about

At the Magicians’ Convention

Jason England – gambling, cheating and cardshark demonstrations

A few days ago, I joined a discreet gathering in the basement of the St Bride’s Printing Library just off Fleet St. The exterior door was shut and there was no sign outside to advertise that several hundred people were crammed together in the hidden auditorium created from a former swimming pool beneath this lofty Victorian Institute. Even if you had seen the participants come and go, you would have no reason to suppose that anything special was going on. Even if the casual passerby were to consider the crowds teeming excitedly into the narrow streets behind Ludgate Circus, they might assume these were chartered surveyors or procurement managers, or representatives of some other familiar occupation. To the untrained eye, there was nothing to reveal that some of the world’s greatest magician were gathered there to swap tricks.

The occasion was the Fortieth International Magic Convention – an event started by magician Ron MacMillan (known as “The Man with the Golden Hands”) in 1972 and continued today by his children, Martin & Georgia MacMillan of the International Magic Shop in the Clerkenwell Rd. And, thanks to them, photographer Mike Tsang and I were granted the privilege to go behind the scenes and meet some living legends of prestidigitation.

“All the most brilliant minds in magic are here,” James Freedman, the pickpocket magician (known as “The Man of Steal”) promised me, as he led us through the throng, “If a bomb dropped today there wouldn’t be any conjuring in this country for the next fifty years.”

The first to loom out of the gloom in the darkened theatre was Max Maven, a mind reader from Hollywood. Dressed head to toe in black, he peered at me benignly through his pebble lenses while standing composed with arms crossed, explaining that he knew Ron MacMillan and had been attending annually since the nineteen seventies. “This is the place where the magicians you want to meet come,” he revealed delightedly, hinting at further mysteries enacted behind closed doors, “the social side is very important with all kinds of late night sessions at the hotel bar.”

At seven years old, Jason England saw a card trick on television at home in Knoxville and thirty years later he lives in Las Vegas, a practising magician who also operates as a gambling protection consultant, helping the casinos to spot card cheats. In spite of his open, easy-going personality Jason has a razor sharp mind. He specialises in gambling, cheating and cardshark demonstrations and, although appears to carry it off with alacrity, tossing cards here and there playfully, another conjurer whispered in my ear that he is – “one of the best in the world.”

John Archer and Alan Hudson were the first British magicians that I met and – in significant contrast to their American counterparts – they were also both comedians who pretended not to have clue what they were doing, concealing their expertise behind a facade of incompetence and confusion. Yet John, a gruff former policeman turned conjurer, admitted he was the first ever to fool Penn & Teller and has performed in more than forty-three countries.

New Yorker, Mark Setteducati, dressed head to foot in black satin and sporting a mop of curls, peered out from underneath his fringe with a sly smile. “Misdirection doesn’t change,” he confided to me, “Most good magic is as much about the presentation as it is about the secret – but you need a secret, because without the secret it’s not magic, it’s just theatre.” An inventor of toys as well as a magician, Mark was waving his pop-up magic book that plays tricks upon the reader and he opened his suitcase to show off his jigsaw puzzle that can be reassembled in an infinite number of ways to create any picture. But then – as if this were not sufficient wonder – he led me to meet the man he described in hushed tones as “Probably the greatest conjurer that ever lived.”

In a shabby dressing room, I was introduced to Lubor Fiedler, the mere mortal behind the Parabox, the Invisible Zone, the Krazy Keys, the Impossible Pen, the Antigravity Rock, the Phantom Clock, the Blue Crystal, the Gozinta Boxes, the Dental Dam trick, the Red Hot Wire and the Spooky Glasses. This is the one magicians worship for his invention of “principles,” not merely new presentations of old ideas – as most conceptions in the world of conjuring are – but creating an endless stream of new tricks that have filtered into the repertoire of every other practitioner in the world.

A mild, dignified gentleman in a sleeveless pullover, Lubor preferred the solace of an empty dressing room to the networking crowd outside. Maybe Lubor has nothing left to prove. Born in Brno in the Czech republic in 1933, as a child he picked up hot bullets from the pavement, fired by machine guns mounted on Nazi planes, before he saw Hitler arrive and speak in the town square. By the age of seventeen, Lubor achieved fame as a boy conjurer and then in 1962 he fled the Soviet Bloc – giving as many as eighteen hundred school magic shows a year to make a living at first, eventually establishing himself as a master on the international circuit and winning acclaim for his inventions.

It was touching to meet this quiet man who had experienced so much and found such an unlikely way to liberate himself through talent and imagination. Yet this was the common pattern amongst everyone I met at the magic convention, these were all people who had constructed out-of-the-ordinary lives for themselves through sheer inventiveness and nerve. Loners who travel the world and perform alone, they embody the true power of magic – transforming their own lives and elevating existence for everyone else in the process.

Max Maven, Mind Reader from Hollwood.

John Archer, Magic Circle Stage Magician of the Year.

Mark Setteducati, Magician and Toy Inventor from New York.

Alan Hudson, Comedy Magician from Hull.

Lubor Fiedler, Legendary Illusionist.

Lubor Fiedler, Boy Magician in 1949

New portraits © Mike Tsang

1949 portraits copyright © Lubor Fiedler

You might also like to read about

Alex Guarneri, Cheesemonger

Alex Guarneri is the big cheese in Spitalfields. The man with the nose for fromage. And a very handsome Gallic proboscis it is, long and elegantly sculpted and extremely sensitive. Wisely, Alex has always followed his nose and it has led him in the direction of all things cheesy – with the result that today le fromage is his existence, his religion and his life. Both a connoisseur and an evangelist of cheese, Alex has lessons to impart. Alex loves to talk cheese. Alex wants to tell you that it is all about timing. Cheeses for all seasons. Alex ensures he gets the cheese direct from the maker when it is at its best and then he matures it in his cave until it is just right, not too ripe. Alex prefers you to be frugal. Be like the church mouse and buy a little piece of cheese. Alex does not want you to keep it until it goes stale. Alex wants you to eat it now.

As a proud Frenchman, Alex sees cheese as an egalitarian birthright. He has no truck with the snobby British notion of posh cheeses as luxury food. In fact, Alex refuses the sell large pieces of cheese or to supply cheeses early for Christmas. Alex suggests you bring him whatever you might afford to spend on cheese at the supermarket – however modest – and he will find you something much better for your money.

Descended from a venerable line of French grocers, Alex and his brother Leo grew up outside Paris where their mother ran a cookery school.“We never had sweets, we had bread, cheese and preserves after school,” he recalled wistfully, sipping his Coca Cola. Working at first as a cashier at Androuet – the pre-eminent chain of cheese shops in France – as a holiday job while he was a student in Paris, Alex graduated to become an affineur, the head of the cave. From there he came to London to the equivalent job at Paxton & Whitfield. “On my first day, they told me I had to deliver the cheese to Buckingham Palace and I thought they were kidding.” he confided to me with the absurd grin of a born republican, before adding,“It was fantastic working there, I met a lot of chefs while I was doing the deliveries to restaurants and in time I went out to meet all the producers too.”

Demonstrating a nose for business as well as for cheese, Alex capitalised upon his privileged knowledge of both British and French cheeses, brokering a deal between Androuet and Paxton & Whitfield that gave him the franchise to open the first Androuet shop in London.“We created a partnership, supplying French cheeses to Paxton & Whitfield and they supply us with English cheeses that we export and sell in France.” he revealed proudly. Starting from a single stall in 2009, Alex and his brother Leo have graduated to a cheese palace – their shop Androuet in the Spitalfields Market with an ever-changing stock of French and English cheese, and a small restaurant with a cheese-inflected menu created by chef Alessandro Granot.

One of a tiny handful in London who know the secrets of ageing cheese, Alex pays scrupulous attention to his precious charges. “The temperature of the room and the humidity are crucial,” he informed me, lifting his eyebrows for emphasis and raising a finger of instruction, before unfurling his hand to illustrate – “The way I touch them and clean off the flower.” (Alex never talks about mould.) “Every week, I remove the flower, so that the cheese creates a new rind, and this makes such a difference to the flavour.” he continued, affectionately cradling a wrinkly specimen and delicately brushing the bloom with his fingers, “I learnt all this in Paris. I was down in my cellar, it was big. You don’t have any people left that you can ask, so instead I tasted everything and that is how I developed my technique, through testing.”

“We only deal with seasonal cheeses in the shop. Every Friday, I ring my cheese producers in France and they tell me what is good now. They send the cheese to Paris and it is delivered here – every Wednesday, I get the cheese from France. We keep cheese for a minimum of a week and for as long as five or six months. You lose weight by keeping cheese and it is sold by weight, that’s why people don’t usually like to do it.”

Indulging in a little spéléologie, we descended deep below the Spitalfields Market to Alex’s magic cave where his cheeses sat ripening, awaiting their destiny in the gloom – acquiring character and personality over time, just as we all do in life. Some were cheeky, others were reserved, yet Alex was encouraging them all towards perfection.

Alex Guarneri is the cheesemonger of the moment.

Alex Guarneri – the man with the nose for fromage.

Photographs copyright © Patricia Niven