William Blake’s Songs of Innocence

In anticipation of the birthday tomorrow of the beloved William Blake – the greatest poet of London – it is my delight to publish his Songs of Innocence of 1789 today. When Blake was developing his copper plate printing technique that would enable him to become his own publisher and be free of the restrictions of others, he wrote, “I must Create a System, or be enslav’d by another Man’s.” So I think we may assume that if Blake were writing now he would embrace the opportunity of publishing his work freely upon the internet.

You may also like to read about

Jock McFadyen, Landscape Painter

Aldgate East by Jock McFadyen

Hidden behind an old terrace facing London Fields is a back street with a scrapyard and a car repair garage, and a row of anonymous industrial units where painter Jock McFadyen has his studio. You enter through a narrow alley round the back to discover Jock in his lair, a scrawny Scotsman with freckles, tufts of ginger hair, and beady eyes that look right through you. Yet such is the modesty of his demeanour, he acted more like the caretaker than the owner – concentrating on the coffee and biscuits, and leaving me to gasp at his vast canvasses of landscapes on a scale uncommon in our age.

With plain titles such as “Dagenham,” “Looking West,” “Pink Flats,” and “Popular Enclosure,” Jock McFadyen evokes the terrain where East London unravels into Essex beneath apocalyptic northern skies, encompassed by an horizon that extends beyond your field of vision when you stand in front of these pictures. The works of man appear insubstantial, either dwarfed by the scale of the landscape or partly obscured by meteorological effects.

Originating from Paisley, Jock has lived and worked in the East End since 1978, with studios in Butler’s Wharf, Bow and the Truman Brewery before arriving in London Fields fifteen years ago. Although he has painted a whole series of epic landscapes of the East End, Jock remains ambivalent about its impact upon his work. “It’s difficult to say how much a place affects you because my real influences are other painters like Lowry and Sickert,” he admitted to me with a shrug, “You’re never just painting what’s in front of your nose, you’re aware of the history of painting.”

“When I was a student at Chelsea in the seventies, the previous generation were the pop artists and my work was quite stark and self-referential.” he confessed with a chuckle, breaking into a shy grin, “But when I became Artist in Residence at the National Gallery in 1981, I realised I couldn’t spend my life just making art about art, so I started painting what I saw in the street – What could be less fashionable?”

“Then in 1991, I got commissioned to design a set for the Royal Ballet. They thought, ‘It’s urban despair, let’s get Jock McFadyen!'” he continued, sipping his coffee with relish, “There were no figures in my design, because the dancers were the figures. And that’s when I realised I had been a landscape painter all along – I’d been painting people in places.”

Once we had reached this point and he had told the story of his self-liberation as an artist, Jock leaned back on his couch and cast his eyes in pleasurable appreciation up to a rusty bicycle frame hanging from the roof. He wanted to talk about his love for Lowry and Sickert. “Lowry was the most committed painter because he had nothing else in his life. I think he spent every day outdoors in his raincoat, knocking out paintings. You believe him, it’s authentic.” Jock assured me fondly. Yet it was Sickert who has provided the inspiration for the current exhibition entitled “After Walter” at Eleven Spitalfields in which, after two decades of landscapes, Jock returns to painting figures. “They’re the first full-blown figures I’ve done,” he declared with a significant nod, “They’re not actual people though, they’re dirty old man fantasies.”

So there we left our conversation, as I set off to the gallery in Princelet St to discover the substance of Jock’s libidinous imagination. But before I departed his studio, I paused to admire a huge canvas of magnificent old rotting warehouses on the River Lea. It occurred to me that Jock came from Glasgow – a decayed port city with a vibrant working class culture – and felt at home in the East End, a location with a similar identity. I saw Jock looking at me and I realised he knew what I was thinking. “If you are a landscape painter you can only paint one place at a time,” he said, anticipating my words “So the question is ‘Are you an East End painter or are you just a landscape painter that happens to live here?'”

Jock McFadyen in London Fields

Looking West

Bud

From Beckton Alp

Goodfellas

Showcase Cinemas

Tate Moss

Pink Flats

Jock & Horseshoe Jake in front of Popular Enclosure

Dagenham

Roman Rd

Jock McFadyen

Black & white portraits copyright © Lucinda Douglas Menzies

Jock McFadyen’s exhibition AFTER WALTER runs at Eleven Spitalfields in Princelet St until 23rd December.

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Six)

Photographer and Ex-Boxer John Claridge has been making regular trips to the East End to take on members of London Ex-Boxers Association. John distinguished himself with some fine shots in Round One, proved a class act with a bravura display of his singular talent in Round Two, commanded the ring in Round Three, showed himself as a potential champion in Round Four, continued his astonishing performance in Round Five and now excels himself in Round Six.

Eddie Lazar (Boxed in the fifties, his name was shortened from Lazarus because at his first fight there was not enough space on the poster.)

John Powell (First fight 1964 – First fight 1969)

Colin Lake (First fight 1961 – Last fight 1970)

Mick Pye (First fight 1956 – Last fight 1966)

Vic Moore (First fight 1965 – Last fight 1969)

Ted Cheeseman (First fight 2007 and still boxing)

Mark Lazarus (Brother of Eddie Lazar, Amateur Boxer & Professional Footballer who scored final goal in 1967 Cup Final))

Johnny Shannon (First fight 1946 – Last fight 1955)

Chas Taylor, LEBA Welfare Officer (First fight 1956 – Last fight 1958)

Dennis Hinson (First fight 1948 – Last fight 1960)

John Docker (First fight 1946 – Last fight 1962)

Photographs copyright © John Claridge

Take a look at

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round One)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Two)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Three)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Four)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Five)

and these other pictures by John Claridge

Along the Thames with John Claridge

At the Salvation Army with John Claridge

A Few Diversions by John Claridge

Signs, Posters, Typography & Graphics

Views from a Dinghy by John Claridge

In Another World with John Claridge

A Few Pints with John Claridge

Some East End Portraits by John Claridge

Sunday Morning Stroll with John Claridge

Tony Hawkins, Retired Pedlar

Tony Hawkins & Paul Gardner

Tony Hawkins was a pedlar selling peanuts and roasted chestnuts in the West End streets for ten years, but after getting arrested and roughed up by the police eighty-seven times his health failed and he retired.

Whereas Tony used to visit Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen in Commercial St regularly to buy thousands of bags for his thriving business, now he just comes to pass the time of day with his old friend Paul Gardner. And it was Paul who effected my introduction to Tony – a man with a defiant strength of character – frail physically yet energised by moral courage and brandishing the dog-eared stack of paperwork from his eighty-seven court cases, immensely proud that he won every one and it was proven he never broke the law once.

Over the centuries, street vendors have always been regarded with suspicion by the authorities while Londoners have cherished these characters for their resilience and wit, celebrating them in popular prints of the Cries of London. Remarkably, Tony’s pitiful catalogue of his wrangles with Westminster Council – who went to extreme lengths just to prevent him peddling nuts in Piccadilly – shows that this age-old ambivalence and prejudice against those who seek to make a modest living by trading in the street persists to the present day.

“I was unemployed as a labourer in Manchester, so I started off as a pedlar. I sold socks, balloons – anything really. A pedlar trades as he travels, and the will to support myself and the bright lights brought me to London. I was peddling around the West End selling peanuts mostly but also chestnuts. I sold flags at football matches too, Chelsea and Arsenal.

In the nineteen eighties, a sergeant took me to Bow St Magistrates Court for selling peanuts in Piccadilly. So I went along, it was no big deal. I admitted I was trading and I was a licenced pedlar. In court, they were amazed because thay hadn’t seen many pedlars, there were only half a dozen in the West End. I won the case and I went to shake the sergeant’s hand afterwards, but he pushed me away and said it wasn’t the end of it. He told me he’d do everything in his power to make sure I never worked again and he hounded me after that. He said, “If you’re going to do it again, we will arrest you again,” and I’ve been arrested more than eighty times and spent nights in cells. I’ve been roughed up so many times by policemen and council enforcement officers that I had to get a hidden camera because I feared for my safety.

They confiscated the equipment from me every time I was charged with the offence of street trading without a licence, when I had a pedlar’s licence issued in accordance with the Pedlar’s Act of 1871. The original Act was passed in the eighteenth century so that veteran soldiers could trade in fish, fruit, vegetables and victuals, and be distinguished from vagabonds. Anyone over the age of seventeen can get a pedlar’s licence as long as you have no criminal record. According to the Bill of Rights and the Magna Carta, every person in this country has the right to trade.

I went to the High Court once when they found against me and the judge overturned it in my favour. But then in 2000 they brought in the Westminster Act because of people like myself. Westminster Council juggled the words so that it states that pedlars are only allowed to go door to door. Prior to that Act, we were allowed to pedle lawfully anywhere in the United Kingdom but now the Act is also being used to stop pedlars in Newcastle, Liverpool, Manchester, Warrington and Balham. Yet Acts and Statutes are not laws, they are rules for the governance, accepted only by consent of the populace.

Once I went to get my stuff back from Westminster Council and I met the Manager of Licencing & Street Enforcement. I asked him, “Why do you continue to waste the money of the council tax payers with so many cases against me when you haven’t won a single one?”

“Your lawyer, Mr Barca, I’m sick of him,” he said, “He only represents the lower end of the market like you, and pimps and prostitutes.” Later, he denied it and said he had a witness too, but I had recorded him and he had to pay four thousand pounds in damages to Mr Barca.

After being hounded by the council and the police so many times, I’ve become narked and with good reason. Over the years, it has cost me fortunes to pay the legal costs. I had to work to earn all the money to pay for it. I regard myself as downtrodden because I was never allowed to benefit from my hard work, but if I had been allowed to continue trading, I could have owned a house by now and have some money in the bank.

People say to me,“Why have you done it?” I have done it because I believe in the right to trade freely as a human right.”

Although Tony is now retired, living comfortably in sheltered housing, he has become a self-taught yet highly articulate expert in the law regarding pedlars and street trading, and is involved with the Pedlars Information & Resource Centre. Despite losing his health and his livelihood, Tony has acquired moral stature as a human being, passionate to support others suffering similar harassment simply because they choose to exercise their right to sell in the street. With exceptional perseverance, acting out of a love of liberty and a refusal to be intimidated by authority, Tony Hawkins is an unacknowledged hero of the London streets.

Any pedlar that wishes to contact Tony can do so at TonyTHawkins@aol.com

Tony shows his pedlar’s licence and the paperwork from his eighty-seven court cases.

Tony Hawkins at Gardners Market Sundriesmen.

Tony Hawkins, unacknowledged hero of the London streets.

You may also like to read about

The Streets of Old London

Piccadilly, c. 1900

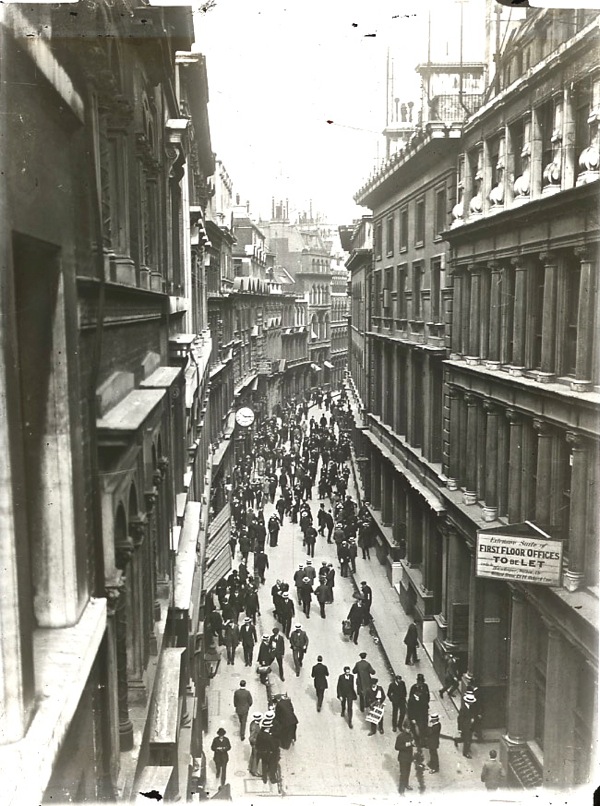

In my mind, I live in old London as much as I live in the contemporary London of here and now. Maybe I have spent too much time looking at photographs of old London – such as these glass slides once used for magic lantern shows by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society at the Bishopsgate Institute?

Old London exists to me through photography almost as vividly as if I had actual memory of a century ago. Consequently, when I walk through the streets of London today, I am especially aware of the locations that have changed little over this time. And, in my mind’s eye, these streets of old London are peopled by the inhabitants of the photographs.

Yet I am not haunted by the past, rather it is as if we Londoners in the insubstantial present are the fleeting spirits while – thanks to photography – those people of a century ago occupy these streets of old London eternally. The pictures have frozen their world forever and, walking in these same streets today, my experience can sometimes be akin to that of a visitor exploring the backlot of a film studio long after the actors have gone.

I recall my terror at the incomprehensible nature of London when I first visited the great metropolis from my small city in the provinces. But now I have lived here long enough to have lost that diabolic London I first encountered in which many of the great buildings were black, still coated with soot from the days of coal fires.

Reaching beyond my limited period of residence in the capital, these photographs of the streets of old London reveal a deeper perspective in time, setting my own experience in proportion and allowing me to feel part of the continuum of the ever-changing city.

Ludgate Hill, c. 1920

Holborn Viaduct, c. 1910

Woman selling fish from a barrel, c. 1910

Trinity Almshouses, Mile End Rd, c. 1920

Throgmorton St, c. 1920

Highgate Forge, Highgate High St, 1900

Bangor St, Kensington, c. 1900

Ludgate Hill, c. 1910

Walls Ice Cream Vendor, c. 1920

Ludgate Hill, c. 1910

Strand Yard, Highgate, 1900

Eyre St Hill, Little Italy, c. 1890

Eyre St Hill, Little Italy, c. 1890

Muffin man, c. 1910

Seven Dials, c. 19o0

Fetter Lane, c. 1910

Piccadilly Circus, c. 1900

St Clement Danes, c. 1910

Hoardings in Knightsbridge, c. 1935

Wych St, c.1890

Dustcart, c. 1910

At the foot of the Monument, c. 1900

Pageantmaster Court, Ludgate Hill, c. 1930

Pageantmaster Court, Ludgate Hill, c. 1930

Holborn Circus, 1910

Cheapside, 1890

Cheapside ,1892

Cheapside with St Mary Le Bow, 1910

Regent St, 1900

Glass slides copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

Two Announcements

At the Drapers’ Hall

The Drawing Room

As long ago as 1180, the Drapers in the City of London formed a Guild to protect their interests as small traders and help members who fell into distress. The full title of the company was, “The Master and Wardens and Brethren and Sisters of the Guild or Fraternity of the Blessed Mary the Virgin of the Mystery of the Drapers of the City of London.” More than eight hundred years later, it still exists to administer charitable trusts, inheriting headquarters that have been rebuilt over the centuries upon the site of Thomas Cromwell’s house – taken by Henry VIII after Cromwell’s execution at the Tower in 1540 and sold to the Drapers in 1543.

For years, I walked down Throgmorton Avenue and peered through the railings at the Mulberry trees growing there with out knowing that this tiny enclave of greenery in the heart of the city was the last remnant of Thomas Cromwell’s garden. Consequently, I was fascinated to visit the Drapers’ Hall this week and explore the chambers of the ancient livery company arranged around a hidden courtyard, following the ground plan of the great medieval hall that once stood upon this site. Until then, I had no idea that these palatial spaces existed, sequestered from the idle passerby.

Cromwell’s mansion was destroyed by the Great Fire of 1666, then rebuilt to designs by Edward Jarman in the sixteen seventies and later remodelled in each of the subsequent centuries to arrive at the rambling construction I encountered, which delivers some breathtaking architectural contrasts as you walk from one space to another. Offices occupy the ground floor that give no hint of the grandeur above, unless you step into the courtyard and raise your eyes to peer through the tall windows upon the first storey where the gleam of vast chandeliers reveals lofty painted ceilings. Standing there in the stone yard surrounded by an arcade embellished with heads of the prophets, you might be in Venice or Rome.

A magnificent eighteen nineties staircase by Thomas Graham Jackson, lavishly encrusted with alabaster and red emperor and green chipolina marble, and light by a five thousand piece chandelier, offers a suitable introduction to the wonders at the top, where the grand Dining Room awaits on your left and the even grander Drawing Room on your right. Overlooking the garden, the Dining Room is one of the oldest chambers at the Drapers’ Hall, dating from the seventeenth century yet heavily embellished with coats of arms in the mid-nineteenth century to create a shining firmament overhead, glistening in diffuse chandelier light.

Crossing the landing, you enter the Court Room where Nelson and Wellington face each other from full-length portraits at either end. Lit by tall windows overlooking the courtyard, even the grandeur of this space gives no indication of the vast Livery Hall beyond. In the sepulchral gloom, larger than life-size portraits of British monarchs line up around the walls of this cathedral-like space, where no sound of the city penetrates and the depth of silence hums in your ears. Incredibly, the embellishment in this ornate room was simplified in the eighteen nineties because the original decoration was so elaborate that it prevented the entry of light.

A narrow corridor leading from the hall and overlooking the courtyard holds the company’s succession of charters including Edward III’s Patent of 1364 followed by those granted by James I, Elizabeth I and our own Elizabeth II. Facing the Livery Hall across the courtyard is the Drawing Room, a chamber worthy of any of the royal palaces of Europe. Created by architect Herbert Williams and interior designer John G. Crace, it remains as they left it in 1868, – an exquisitely modulated symphony of gilt panelling and mirrors, glowing golden in the cool northern light.

Over-awed by the majesty of the building and distracted by the collection of old paintings worthy of any museum, I rubbed my bleary eyes when I found myself back in the dusty streets around Liverpool St Station in the grey dusk of a November’s afternoon, and it caused me to question whether my visit to the Drapers’ Hall had, in fact, been an apparition conjured by a daydream.

Bearded Persians by Henry Pegram flank the Throgmorton St entrance.

Staircase designed by Thomas Graham Jackson in the eighteen nineties.

A five thousand piece chandelier lights the staircase.

Jason and the Golden Fleece, portrayed upon the celiing of the Court Dining Room

Looking from the Drawing Room through to the Dining Room.

The Drawing Room by architect Herbert Williams and interior designer John G. Crace, 1868.

The Drawing Room c. 1920

The Shepherd Boy by Thorwaldsen, 1893.

The Livery Hall, c. 1920

The Livery Hall

The Livery Hall c.1920

The Livery Hall

The Livery Hall, c. 1890

This dial in the Livery Hall indicates the wind direction.

The Courtyard c. 1920

The last remnant of Thomas Cromwell’s garden.

The Garden, c. 1920

Glass slides courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You can visit the Draper’s Hall on 3rd December for the Wellbeing of Women Christmas Fair 11am-8pm.

You may also like to read about