At the Hula Hoop Festival

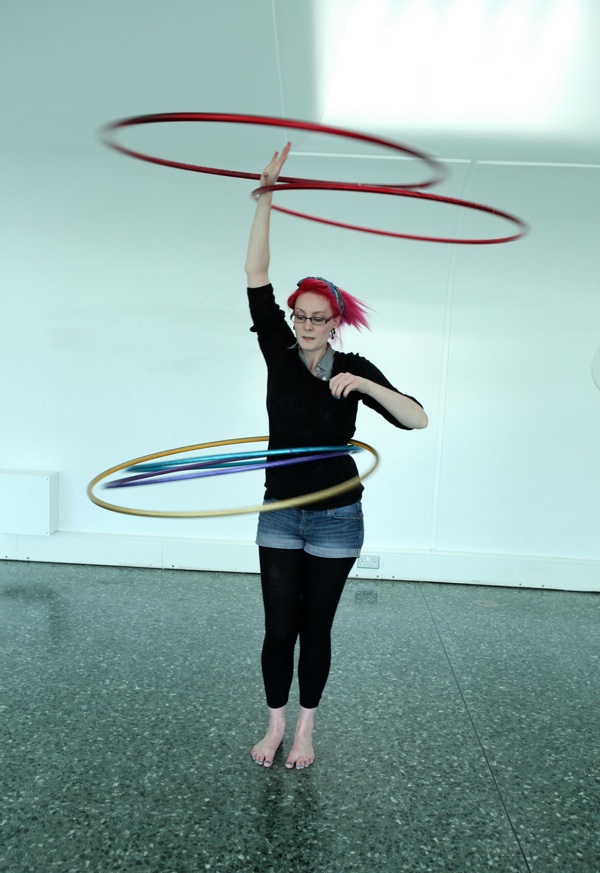

Lyndsay Hooper

When I heard that London’s top Hula Hoop Artists were gathering at the Mile End Pavilion for their annual Hoopfest, I could not resist going along with Contributing Photographer Colin O’Brien to join the hoopla. I can think of no more exuberant expression of the joy of being alive than the art of Hula Hooping, and we were exhilarated to be surrounded by so many talented Hula Hoopers demonstrating a wider range of techniques and styles with the humble hoop than I ever imagined possible.

The festival is the inspiration of Anna the Hulagan & Rowan Bad-timing-Boy Byrne, a former boxer. “When you are boxing you don’t want your elbows to drop because that’s your guard, so I learnt to Hula Hoop to help with my defensive technique, “ Rowan, one of the lone males at the festival, admitted to me with a blush. “I was at a party in Shoreditch and Rowan asked to borrow my Hula Hoop to have a try,” explained Anna, continuing the story and revealing how she met Rowan and found love through Hula Hooping, “So then I started teaching him and we began dating, and now we are getting married.”

An intoxicating atmosphere of jubilation prevailed at the festival and many of the participants confided to me that Hula Hooping made them happy, as well as advocating the health benefits, the social possibilities and the limitless potential for fun. If you did not know it already, there is a Hula Hoop revival sweeping the globe – and it made my heart leap to encounter it here in the East End this week.

Anna the Hulagan & Rowan Bad-timing-Boy Byrne found love through the Hula Hoop.

Silvia Pavone

Jennifer Farnell – “If I’m in a bad mood, I do bit of Hula Hooping and I immediately feel better.”

Helen Whitcher – “I wrote some music for a Hula Hooper and she gave me a hoop, so then I got interested. I find it really relaxing after a hard day at the office.”

Scarlett San Martin – “I always dance alone in my room, but I got a large room, so a Hula Hoop helped me to fill the space.”

Tina Johnson – “Hula Hooping has taught me patience, because if you become frustrated you get nowhere – so it makes you calm.”

Tracey Chin

Chloe Hannah Lloyd

See Ying Yip – “It’s addictive, I used to be ten stone but now I am seven stone and I just love dancing where I never used to dance before.”

Lyndsay Hooper – “Hooper by name, hooper by nature.”

Amanda Long

Obie Campbell

Anna the Hulagan & Rowan Bad-timing-Boy Byrne

Photographs copyright © Colin O’Brien

David Robinson, Chairman of the Repton Boxing Club

David shows a bit of action with the punchbag at his stoneyard in Ezra St

“I’m nothing, I’m nobody, I’m David Nothing,” declared David Robinson, Chairman of the Repton Boxing Club in Cheshire St, by way of introducing himself, when Contributing Photographer Simon Mooney & I turned up to meet him last week. Tony Burns, Head Coach, chipped in too, suggesting to me helpfully, “You don’t have to say ‘David,’ say ‘Ignore it!'” Such high spirits were an indicator that the Repton has enjoyed another successful season and now, following the usual pattern of the year, the officers will retire on 30th May until they are re-elected in September – “Whether we like it or not!” chuckled David, rubbing his hands with glee.

“I’m an immigrant, I’m not an East Ender – but it took a boy from the West End to show them how to run a boxing club in the East End !” he continued, bragging to counteract his initial modesty and waving his hands around excitedly as we entered the Club, housed in a glorious former bath-house lined with boxing memorabilia, where David has been Chairman for the last quarter century.“We’ve been here forty years and we’ve got a thousand year lease which I personally negotiated myself,” he added with a swagger.

Once you are inside the Club, the humidity increases suddenly as you enter a space where dozens of figures are in motion, punching the air, or punchbags, or each other, with balletic grace and insistent rhythms. The energy and movement creates a volatile spectacle, illuminated by dramatic rays of sunlight from a glass lantern high in the roof and intensified by a cacophony of sound bouncing off the tiled walls pasted with old boxing posters.

Over the course of one practice session at the gym and a rainy afternoon next day at his stoneyard, David told me his story. It led me to understand something of his motives in nurturing the extended mutually-respecting family that exists at the Repton and which has been key to its ascendancy, becoming Britain’s most famous boxing Club.

“I’m not an East End boy, I was born in Old Compton St into a close Soho community composed of Irish, Italian, Cypriots, Maltese and English, and I went to St Patrick’s School in Soho Sq. Then we moved to Cleveland St, north of Oxford St, where I grew up. The house was derelict, it was bomb-damaged, no running water or power, and there was a tarpaulin in place of a roof.

I had no parents, my dad was an abusive alcoholic and my mum had left, so I had to take care of my younger brother Leon alone and protect him from my dad. I remember going down to the Kings’ Cross Coal Depot on a Saturday to get half a crown for helping out. The coal merchants would load up from the coal mountains at the rear of the station and then, as the trucks drove out, they’d pick the biggest boy from those waiting outside for a day’s work carrying sacks of coal. For half a crown, you could go to the pictures and out on a Saturday night, and have a few bob left for Sunday.

We made our own scooters from planks of wood and cut out a little groove for a ball-bearing at either end, they were the wheels. We used a tarry block from the street to secure the whole thing together and nailed beer bottle tops on the front – as identification to show which street you were from and which gang you were in, blue for this street or green for that one. Once you’d cleaned up the tarry blocks from the street, you could stand on a corner in Great Titchfield St, which was the nearest market, and sell them for a penny a bundle. We’d go down to Covent Garden Market with a sack at five in the morning and help ourselves to carrots, all the poor kids in the West End did that. It was what everyone did. You didn’t take strawberries, just vegetables. The drivers had driven through the night from Kent, and they just wanted to have a nap and drive back. You’d ask them, and they’d let you climb on top of the lorry and help yourself.

My wife Carol is from Bethnal Green and, when I met her in 1960, I was only a lad of fifteen and she was sixteen – and I had never been to the East End. I got out of the tube in Bethnal Green and I thought, ‘So this is the East End.’ We got married here in 1965 at Our Lady of the Assumption, opposite York Hall in Old Ford Rd. When I took her to the West End, she said, ‘This is fantastic, they’ve got more community spirit here than in the East End.’ It’s true. There’s twenty-two boys that I was at school with at St Patrick’s in Soho that I’m still in touch with. We meet in a cafe at the back of Holborn on the last Friday of every month, and have breakfast and a chat about life.

I got an apprenticeship as a plumber and, after Carol & I got married, we ended up living in one room in Southgate Rd where we had our first baby Terrence. We were moved by Greater London Council to Camberwell which I didn’t like but we had a bathroom with hot water and a room for my boy – so you took what you were given. We lived there five and a half years, and that’s where I started my company Rominar, Stone Restoration. It took us two years to save the deposit on a house, by then I had two more children, Jamie and my daughter Karen, and we moved to Wanstead, where I’ve remained ever since. I moved my business to Ezra St, Bethnal Green, from Camberwell where I’d been working out of a garage.

My second son, Jamie, was a bit of a boisterous lad. He got in scuffles in the playground and became generally unruly, so I took him along to the Repton Boys’ Boxing Club one Saturday. The coach Billy Taylor said, ‘He’s fat,’ I said, ‘He’s just not getting enough exercise.’ He went every Saturday and he worked his way up from the juniors to the seniors, and won the National Schoolboy Championship twice. The Repton boys have won seven National Schoolboy titles in a day – twice – in 1980 and 1983. We are the only Club to have ever done that!

Jamie went pro in the mid-eighties. I was fully involved, I was not a boxing trainer but I was very strict with the boys. I took seven boys to Liverpool once and they all lost, they gave up. I said to them, ‘What’s the matter with you? You’ve got no guts and no glory.’ I couldn’t say anything to them on the bus coming back and I didn’t speak to them for three months after.

In 1988, Bill Cox from the Amateur Boxing Association asked me to join the committee. He said, ‘I need to see you, I’ve got lung cancer and I’ve got six months to live. I want to you to come in as Vice-Chairman and when I die I want you to take over.’ I was very sad to see him go and I was at his bedside on the day he died. I put in place ways to make the club financially stable – boys need medical examinations, we have to pay for trips, accommodation for the boxers and the trainers. When I took over there was fifteen hundred pounds in the bank but we are on a much stronger basis now, and my West End contacts have proved a great support to the Club.

I say to the lads, I’ve always worked since I was fourteen because I had no mum or dad. But it’s hard for lads to get work nowadays because there’s all this paperwork, even to get a job on a building site. Once I got my apprenticeship, I could go to any site and get a job.

I’m the spokesman, I explain to people what the Repton is all about. I love it, it’s my life. I’m sixty-seven and I’m sure I’ll be here until I’m seventy . Some of these lads, I know their background and if they weren’t in the Club, they’d be out on the street, doing drugs and getting involved in crime. All we ask is, we expect respect.”

David contemplates the photo of his brother Leon, now deceased.

David sees off his brother Leon on the train to Cornwall from Paddington, 1962. “I sent him to stay with our mother, he was better off being with her than with us. I was trying to protect him from being beaten up by our drunken abusive father.”

David with Carol, his wife-to-be, on their first holiday together, Falmouth 1964. “We saved up a lot of money and took a coach from London, it seemed like a hundred hours to get there. Carol said to me, ‘It’s nice but I prefer the West End of London.'”

“When Carol met my mother Constance,” Falmouth 1964

David with his son Terry, Southgate Rd, 1966

David, Terry & Carol.

David with his sons, Jamie and Terry , and brother-in-law Johnny in Camberwell, 1970

“Me and my brother Ronnie, when we had a stoneyard up the Holloway Rd.”

David with his son Jamie who won the National Schoolboy Championships twice.

“My West End pals” David with David and John Grosvenor , childhood friends who grew up in Bedfordbury, Covent Garden.

David with Sugar Ray Leonard and one of the trainers.

David welcomes Prince Philip and the Mayor of Bethnlal Green to the Repton Boxing Club, 2004

David with some of the Repton Boys at the Dockers’ Club, Belfast 2003

David contemplates Amir Khan’s signature upon the wall of fame at the Repton.

David scrutinizes the boxers at practice.

David with head coach Tony Burns.

David at his stoneyard in Ezra St, Bethnal Green. “This is where it all happens – where you get the swearing in the morning and then swearing in the afternoon.”

“I prefer doing jobs in the West End, then I can drop in and see my pals.”

David and his son Jamie work together in the family business.

new photographs copyright © Simon Mooney

You may also like to read these other boxing stories

Ron Cooper, Lightweight Champion Boxer

Sammy McCarthy, Flyweight Champion

Sylvester Mittee, Welterweight Champion

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round One)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Two)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Three)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Four)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Five)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Six)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Seven)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Eight)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Nine)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Ten)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Eleven)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Twelve)

Hazuan Hashim’s Whitechapel Skies

For many years, Hazuan Hashim has lived on the eleventh floor of a tower block in Whitechapel – looking to the west, he can see the financial towers of the City of London and looking to the east, he sees the new Royal London Hospital. “I love living up high in London,” he admitted to me, “the first thing I do when I wake up is to go to the window and take a picture. Then I come back for lunch and take a couple more shots, but the most exciting time is between five and eight o’clock when the light is changing every ten minutes.”

7:57pm, 27th April

8:22pm, 27th April

7:46pm, 29th April

2:43pm, 8th May

6:56pm, 8th May

10:02am, 11th May

4:30pm, 11th May

4:31pm, 11th May

4:32pm, 11th May

4:35pm, 11th May

4:42pm, 11th May

6:00pm, 11th May

6:01pm, 11th May

6:32pm, 11th May

6:42pm, 11th May

7:11pm, 11th May

8:46am, 13th May

6:10pm, 13th May

6:22pm, 13th May

6:37pm, 13th May

photographs copyright © Hazuan Hashim

In a Well in Spitalfields

Twenty years ago, eighteen wooden plates and bowls were recovered from a silted-up well in Spitalfields. One of the largest discoveries of medieval wooden vessels ever made in this country, they are believed to be dishes belonging to the inmates of the long-gone Hospital of St Mary Spital, which gave its name to this place. After seven hundred years lying in mud at the bottom of the well, the thirteenth century plates were transferred to the Museum of London store in Hoxton where I went to visit them yesterday as a guest of Roy Stephenson, Head of Archaeological Collections.

Almost no trace remains above ground of the ancient Hospital of St Mary yet, in Spital Sq, the roads still follow the ground plan laid laid out by Walter Brune in 1197, with the current entrance from Bishopsgate coinciding to the gate of the Priory and Folgate St following the line of the northern perimeter wall. Stand in the middle of Spital Sq today, and you are surrounded by glass and steel corporate architecture, but seven hundred years ago this space was enclosed by the church of St Mary and then you would be standing in the centre of the aisle where the transepts crossed beneath the soaring vault with the lantern of the tower looming overhead. Stand in the middle of Spital Sq today, and the Hospital of St Mary is lost in time.

In his storehouse, Roy Stephenson has eleven miles of rolling shelves that contain all the finds excavated from old London in recent decades. He opened one box containing bricks in a plastic bag that originated from Pudding Lane and were caked with charcoal dust from the Fire of London. I leant in close and a faint cloud of soot rose in the air, with an unmistakable burnt smell persisting after four centuries. “I can open these at random,” said Roy, gesturing towards the infinitely receding shelves lined with boxes in every direction, “and every one will have a story inside.”

Removing the wooden plates and bowls from their boxes, Roy laid them upon the table for me to see. Finely turned and delicate, they still displayed ridges from the lathe, seven centuries after manufacture. Even distorted by water and pressure over time, it was apparent that, even if they were for the lowly inhabitants of the hospital, these were not crudely produced items. At hospitals, new arrivals were commonly issued with a plate or bowl, and drinking cup and a spoon. Ceramics and metalware survive but rarely wood, so Roy is especially proud of these humble platters. “They are a reminder that pottery is a small part of the kitchen assemblage and people ate off wood and also off bread which leaves no trace.” he explained. Turning over a plate, Roy showed me a cross upon the base made of two branded lines burnt into the wood. “Somebody wanted to eat off the same plate each day and made it their own,” he informed me, as each of the bowls and plates were revealed to have different symbols and simple marks upon them to distinguish their owners – crosses, squares and stars.

Contemporary with the plates, there are a number of ceramic jugs and flagons which Roy produced from boxes in another corner of his store. While the utilitarian quality of the dishes did not speak of any precise period, the rich glazes and flamboyant embossed designs, with studs and rosettes applied, possessed a distinctive aesthetic that placed them in another age. Some had protuberances created with the imprints of fingers around the base that permitted the jar to sit upon a hot surface and heat the liquid inside without cracking from direct contact with the source of heat, and these pots were still blackened from the fire.

The intimacy of objects that have seen so much use conjures the presence of the people who ate and drank with them. Many will have ended up in the graveyard attached to the hospital and then were exhumed in the nineties. It was the largest cemetery ever excavated and their remains were stored in the tall brick rotunda where London Wall meets Goswell Rd outside the Museum of London. This curious architectural feature that serves as a roundabout is in fact a mausoleum for long dead Londoners and, of the seventeen thousand souls whose bones are there, twelve thousand came from Spitalfields.

The Priory of St Mary Spital stood for over four hundred years until it was dissolved by Henry VIII who turned its precincts into an artillery ground in 1539. Very little detail is recorded of the history though we do know that many thousands died in the great famine of 1258, which makes the survival of these dishes at the bottom of a well especially plangent.

Returning to Spitalfields, I walked again through Spital Sq. Yet, in spite of the prevailing synthetic quality of the architecture, the place had changed for me after I had seen and touched the bowls that once belonged to those who called this place home seven centuries ago – and thus the Hospital of St Mary Spital was no longer lost in time.

Sixteenth century drawing of St Mary Spital as Shakespeare may have known it, with gabled wooden houses lining Bishopsgate.

“Nere and within the citie of London be iij hospitalls or spytells, commonly called Seynt Maryes Spytell, Seynt Bartholomewes Spytell and Seynt Thomas Spytell, and the new abby of Tower Hyll, founded of good devocion by auncient ffaders, and endowed with great possessions and rents onley for the releffe, comfort, and helyng of the poore and impotent people not beyng able to help themselffes, and not to the mayntennance of chanins, preestes, and monks to lyve in pleasure, nothyng regardyng the miserable people liying in every strete, offendyng every clene person passyng by the way with theyre fylthy and nasty savours.” Sir Richard Gresham in a letter to Thomas Cromwell, August 1538

Finely turned ash bowl.

Fragment of a wooden plate

Turned wooden plate marked with a square on the base to indicate its owner.

Copper glazed white ware jug from St Mary Spital

Redware glazed flagon, used to heat liquid and still blackened from the fire seven hundred years later.

White ware flagon, decorated in the northern French style.

A pair of thirteenth century boots found at the bottom of the cesspit in Spital Sq.

The gatehouse of St Mary Spital coincides with the entrance to Spital Sq today and Folgate St follows the boundary of the northern perimeter .

Bruyne:

- My vowes fly up to heaven, that I would make

- Some pious work in the brass book of Fame

- That might till Doomesday lengthen out my name.

- Near Norton Folgate therefore have I bought

- Ground to erect His house, which I will call

- And dedicate St Marie’s Hospitall,

- And when ’tis finished, o’ r the gates shall stand

- In capitall letters, these words fairly graven

- For I have given the worke and house to heaven,

- And cal’d it, Domus Dei, God’s House,

- For in my zealous faith I now full well,

- Where goode deeds are, there heaven itself doth dwell.

(Walter Brune founding St Mary Spital from ‘A New Wonder, A Woman Never Vexed’ by William Rowley, 1623)

You may also like to read about

New Delivery System

A new delivery system for subscribers is now in place and we beg your indulgence for any teething problems, strange deliveries or other curious anomalies that may occur while we get it working smoothly.

The Tower of Old London

A contemplative moment at the Tower

Rummaging through the thousands of glass slides from the collection of the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society, used for magic lantern slides a century ago at the Bishopsgate Institute, I came upon these enchanting pictures of the Tower of London.

The Tower is the oldest building in London, yet paradoxically it looks even older in these old photographs than it does today. Is it something to do with the straggly beards upon the yeoman warders? Some inhabit worn-out uniforms as if they themselves are ancient relics that have been tottering around the venerable ruins for centuries, swathed in cobwebs. Nowadays, yeoman warders are photographed on average four hundred times a day and they have learnt how to work the camera with professional ease, but their predecessors of a century ago froze like effigies before the lens displaying an uneasy mixture of bemusement and imperiousness. Their shabby dignity is further undermined in some of these plates by the whimsical tinter who coloured their uniforms in clownish tones of buttercup yellow and forget-me-not blue.

As the location of so many significant events in our history, the Tower carries an awe-inspiring charge for me. And these photographs, glorying in the magnificently craggy old walls and bulbous misshapen towers, capture its battered grim monumentalism perfectly. Today, the Tower focuses upon telling the stories of prisoners of conscience that were held captive there rather than displaying the medieval prison guignol, yet an ambivalence persists for me between the colourful pageantry and the inescapable dark history. In spite of the tourist hordes that overrun it today, the old Tower remains unassailable by the modern world.

The Ceremony of the Keys, c.1900

Salt Tower, c. 1910

Byward Tower, c.1910

Bloody Tower, c. 1910

The Tower seen from St Katharine’s Dock, c.1910

Tower Green, c.1910

View from Tower Hill, c, 1900

Upon the battlements, c. 1900

View from the Thames, c. 1910

Bell Tower, c.1900

Bloody Tower, c. 1910

Courtyard at the Tower, c.1910

Byward Tower, c 1910

Yeoman warders at the entrance to Bloody Tower, c. 1910

Vegetable plot in the former moat adjoining the Byward Tower, c.1910

Byward Tower, c. 1900

Water Lane, c 1910

Rampart, c 1900

Yeoman Gaoler – “displaying an uneasy mixture of bemusement and imperiousness.”

Middle Tower, c. 1900

Steps leading from Traitors’ Gate, c. 1900

Steps inside the Wakefield Tower, c. 1900

The White Tower, c. 1910

Royal Armoury, c. 1910

Beating the Bounds, c. 1920

Cannons at the Tower of London, c. 1910

Queen’s House, c. 1900

Elizabeth’s Walk, Beauchamp Tower, c. 1900

Yeoman Warder, c. 1910

Tower seen from St Katharine’s Dock, c. 1910

Images copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

Residents of Spitalfields and any of the Tower Hamlets may gain admission to the Tower of London for one pound upon production of an Idea Store card. Visit the new exhibition which opens tomorrow Coins and Kings: The Royal Mint at the Tower

You may like to take a look at these other Tower of London stories

Chris Skaife, Raven Keeper & Merlin the Raven

Alan Kingshott, Yeoman Gaoler at the Tower of London

Graffiti at the Tower of London

Beating the Bounds at the Tower of London

Ceremony of the Lilies & Roses at the Tower of London

Bloody Romance of the Tower with pictures by George Cruickshank

John Keohane, Chief Yeoman Warder at the Tower of London

Constables Dues at the Tower of London

The Oldest Ceremony in the World

A Day in the Life of the Chief Yeoman Warder at the Tower of London

Joanna Moore at the Tower of London

and these other glass slides of Old London

The High Days & Holidays of Old London

The Fogs & Smogs of Old London

The Forgotten Corners of Old London

The Statues & Effigies of Old London

Michelle Attfield, Pointe Shoe Fitter

There is one woman, above all others, whom the world’s greatest ballerinas rely upon when it comes to fitting their shoes perfectly, Michelle Attfield of Freed of London. With generous spirit, self-effacing nature and fierce professionalism, Michelle is the queen of the pointe shoe and a legend in ballet circles.

In her half century at Freed, she has fitted ten-year-olds at the Royal Ballet School and accompanied them throughout the course of their careers, subtly modulating the design of their pointe shoes to accommodate both their physical change and the needs of their repertoire. “Sometimes I discover I know more than I think I do, when I look around for an expert and then realise that I have been around longer than anyone.” she admitted to me with a laugh of self-deprecation. In the volatile world of show business, Michelle is one of those rare figures whom dancers can always count upon for unwavering loyalty, appreciation and practical advice.

An ex-dancer and former customer of Freed, who was trained to fit shoes by Mrs Freed herself, Michelle embodies the spirit of the company that she has served all these years and which she delights to speak of. Yet she is the model of discretion, drawing a tactful curtain over the details of her intimate relationships with the great divas, and preferring to enthuse about show-business customers such as her beloved Patrick Swayze who visited Michelle at the shop after hours for extra fittings. “Supine with admiration,” is her verdict upon Mr Swayze.

“I’ve worked for Freed of London for forty-nine years, I’ve given my life to this company. I trained as a dancer but I wasn’t quite good enough to be a ballerina, so I qualified as a teacher and, since Freed’s shop in St Martin’s Lane were always advertising for staff in The Stage, I went along.

I was a Royal Academy of Dance student from the age of ten, so I had known Mrs Freed all that time. It was April and I had a teaching position starting in September, and when I told Mrs Freed she said ‘Why don’t you stay with us and stop all this nonsense?’ I said, ‘But I’ve got a job with the Royal Ballet.’ So I went to work at Freed permanently and never looked back. I tried to leave once when my daughter was born but, luckily for me, some of my customers refused to deal with anyone else. So they rang me and said, ‘You’ve got to come back.’

She was a monster. Mr Freed made shoes but Mrs Freed made the business. She was the dynamo. He was a shoemaker and a good one, she was a milliner. He did the making and she did the sewing. He invented the concept of making the shoe to fit the foot, prior to that they were very stylised, they propped you up but they didn’t let you dance. This development coincided with choreographers like Frederick Ashton and John Cranko wanting a little more and dancers who were willing to give a little more, and our shoes helped them to do it.

Mrs Freed visited the factory every day at seven-thirty and then she went and ran the shop all day – and she did that every day. I discovered the reason they always advertised in The Stage was because no-one could work for Mrs Freed. People exited from the shop very quickly, girls used to start in the morning and leave in the afternoon. I’d come back from lunch and ask ‘Where has she gone?’

Mr & Mrs Freed loved dancers but they didn’t want to go to the ballet. ‘No dear, you take the tickets and go to the ballet,’ they’d say to me, ‘we’ve had enough of that all day.’ You had to work uber-hard but I had been a dancer and dancers are used to hard work – class in the morning, rehearsal in the afternoon and performance in the evening. People either left at once or stayed forever, and it was the most wonderful place to work if you loved ballet – I fitted Margot Fonteyn!

I learnt to dance with one of the founder members of the Royal Academy of Dance and I learnt to fit shoes with Mrs Freed – the perfect foundation for this job. I try to be the bridge between the aspiration of the shoe and the reality of what can be achieved. Because Freed shoes are handmade, we can deliver exactly what an individual dancer needs and that’s why we have our reputation. A pointe shoe is a tool of the trade for a dancer, the shoe has to perform whatever she has to perform and, while a student may require longevity, a professional needs a show purposed for performance. The Freed pointe shoe is a chameleon because it will do anything for anyone.

I’ve fitted so many dancers that wherever I go in the world someone will come up and say, ‘Hello Michelle, I didn’t know you were going to be here.’ I’ve been all over to fit shoes, Japan, Australia, America, Milan, Verona, Paris – it goes on and on. But my greatest pleasure is what I regard as my ‘home companies,’ Royal Ballet, Birmingham Royal Ballet, English National Ballet, Scottish Ballet and Northern Ballet. I sit cross-legged on the floor and dancers come and stand in front of me, and I put shoes on them and decide which maker’s shoes would be best for them to wear. They chose the size but I choose the maker. It has to be a relationship of trust. I look at the whole dancer not just the feet. I say, ‘I know what you want and I’ll do it.’ You want the shoe to fit the dancer so well that you see the dancer not the shoe, you don’t want to see the shoe. And it’s a great feeling when you’ve got them where they want to be.

I think how lucky you are if you are involved with dance. Mine is a job that will never end because there will always be ballet. I used to take my daughter Sophie to the factory and she’d be crawling around on the floor getting dirty while I was picking up shoes. When she was eight, she stood in the wings when Nureyev was dancing, and she turned to me and asked ‘May I have a sandwich?’ She worked in the shop as a Saturday girl and Saturday in our shop is a baptism of fire. Then she went off to work in finance but after she got married, she asked to come back and now accompanies me when I do fittings. I’ve got to start handing over to her because I want to be like the Cheshire Cat, I want to disappear without people noticing me go.”

Michelle with Shevelle Dynott – “One of my darling boys…”

Michelle with Darcy Bussell.

Michelle with Agnes Oaks and Thomas Edur, joint directors of the Estonian National Ballet.

Michelle and fellow shoe fitters at the Freed shop in St Martin’s Lane in the eighties.

Frederick & Dora Freed in their shop.

Michelle in her dancing days.

Portrait of Michelle Attfield copyright © Patricia Niven

You may also like to read about