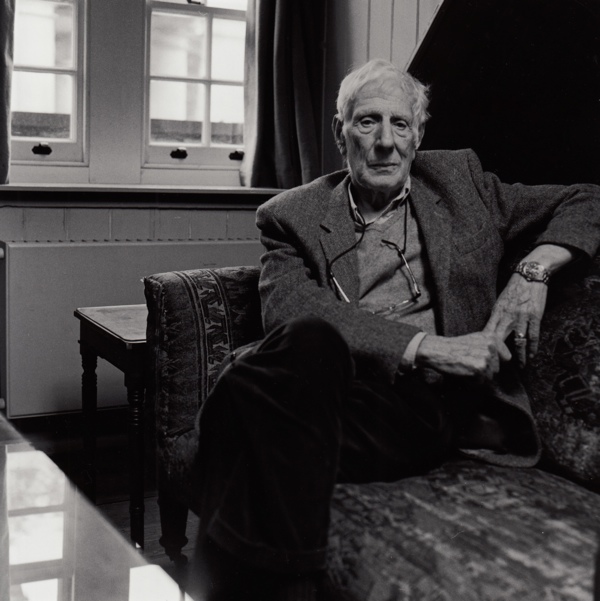

Jonathan Miller in Fournier St

Jonathan Miller, comedian, polymath and celebrated intellectual, visited 5 Fournier St last week, to see the house where his grandfather Abram lived and brought up his family more than a hundred years ago. Abram came to London from Lithuania in 1865 and worked as furrier in the attic workshop, the same room where Lucinda Douglas Menzies took this portrait of Jonathan.

Jonathan does not know when Abram acquired the surname Miller. His grandfather arrived in the Port of London as an adolescent and found work as a machinist in the sweatshops of Whitechapel, where he met Rebecca Fingelstein, a buttonhole hand, whom he married in 1871. Somehow Abram worked his way up to become his own boss during the next ten years, running his own business from premises at 5 Fournier St by the time his son (Jonathan’s father) Emanuel was born in 1892, as the youngest of nine siblings. Emanuel’s sister Clara remembered how the children fell asleep listening to the whirr of sewing machines overhead.

As a supplier of fur hats to Queen Victoria and bearskins to the Grenadiers, Abram aspired to be an English gentleman with a pony and trap. Yet, at 5 Fournier St, the horse had to be kept in the back yard which meant leading it through the front hall, blindfolded in case it reared up at the chandelier.

Jonathan’s aunt Janie wrote her own account of her childhood there – “We lived in a large Queen Anne House in Spitalfields and part of the house was taken over by my father’s business who was a furrier. Needless to say, we all had coats trimmed with fur… My earliest recollection was my first day at the infant school in Old Castle St, and I remember the summer holidays we spent in Ramsgate for two weeks, year after year.”

Janies’s younger brother Emanuel looms large in her narrative – “We moved to Hackney when he was eight and he went to Parminter’s School, and from there got a scholarship to the City of London School and then another scholarship to St John’s College, Cambridge. I remember spending a really lovely week in Cambridge for May Week, attending the concerts etc and meeting all Emanuel’s friends. After leaving Cambridge, he went to the London Hospital in Whitechapel where he qualified as a doctor and served in the 1914 war as a Captain RAMC, and helped to cure the shell-shocked soldiers.” It was a long journey that Emanuel travelled from his father’s beginnings in Whitechapel and, as Janie records, he rejected the family trade in favour of the medical profession, “Emanuel refused to go into the business, as he had been to Cambridge and wanted to be a doctor, and he won the day.”

Jonathan Miller does not recall Emanuel speaking about the East End. “I never talked to my father very much because I was always in bed by the time he was back from his work, so I was completely out of it” he admitted to me, “I am only a Jew for anti-Semites. I say ‘I am not a Jew, I’m Jew-ish!'”

Although intrigued to visit the house where his father was born and where his grandfather worked, Jonathan was unwilling to acknowledge any personal response. “I’m not interested in my ancestry,” he joked, “I’m descended from chimpanzees but I am not interested in them either.” Like many immigrant families that passed through Spitalfields, in Jonathan’s family there was a severance – the generation that moved out and rose to the professional classes chose not to look back. And for Jonathan it was a gap – in culture and in time – that could no longer be bridged, even as we sat in the attic where his grandfather’s workshop had been a century earlier. “I know nothing about their life here,” he confessed to me, gesturing extravagantly around the tiny room and wrinkling that famously-furrowed brow.

As one who has constructed his own identity, Jonathan rejects distinctions of religion and ethnicity in favour of a broader notion of humanity to which he allies himself. Yet he was proud to tell me that his father came back and founded the East London Child Guidance Clinic in 1927, acknowledging where he had come from by bringing his scholarship to serve the people that he had grown up among. “He was interested in juvenile dilinquents and he was really the founder of child psychiatry in this country,” Jonathan explained me, and the work that his father began continues to this day – with the Child & Adolescent Mental Health Services on the Isle of Dogs housed in the Emanuel Miller Centre.

So I found a curious irony in the fact that the son of a leading figure in the understanding of child development in this country should admit to no relationship to his father, and therefore none to his family’s past either. When 5 Fournier St was renovated, the gaps between the floor boards were found to be crammed with clippings of fur and every inch of this old house bears the marks of its three hundred years of use. Constantly, people come back to Spitalfields to search for their own past in the locations familiar to their antecedents, yet often the past they seek is already within them in their cultural inheritance and family traits – if they could only recognise it.

Clearly, Jonathan Miller’s choice to study medicine was not unconnected to his father’s career. When Jonathan reminded me of the familar Jewish joke about asking the way to get to Carnegie Hall and receiving the reply, ‘Practice, practice!’, he suggested that the pursuit of fame as musicians and as comedians had proved to be an important means of advancement for Jewish people. And I could not but think of Jonathan Miller’s own distinguished work in opera and his early success with ‘Beyond the Fringe.’ It set me wondering whether ancestry had influenced him more than he realised, or was entirely willing to admit.

Eighteenth century roof joists, exposed during renovations, still with their original joiner’s numbers which reveal that the roof was made elsewhere and then assembled on site.

Weatherboarding revealed between 3 and 5 Fournier St during renovations, indicating that until the mid-eighteenth century number 5 was the end of the street, before number 3 was built.

Abram Miller arrived from Lithuania in 1865 and is recorded at 5 Fournier St in the census of 1890 .

Wallpaper at 5 Fournier St from the era of Abram Miller.

Watercolour of Fournier St, 1912 – the cart stands outside number 5.

Emanuel Miller was born at 5 Fournier St in 1892.

“I remember the summer holidays we spent in Ramsgate for two weeks year after year.” Emanuel is on the far right of this photograph.

Fournier St in the early twentieth century, number 5 is the third house.

5 Fournier St today, now the premises of the Townhouse.

The hallway where the blindfolded horse was led through.

Emanuel Miller as an old man.

Jonathan Miller

Portraits of Jonathan Miller © Lucinda Douglas Menzies

Barnett Freedman, Artist

I was delighted to invite David Buckman, author of the authoritative book about the East London Group From Bow to Biennale, to write this feature about Barnett Freedman (1901–1958) who was born in Stepney. An equally talented yet less-well-known contemporary of Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious, his work deserves to be enjoyed by a wider audience.

Barnett raises his hat in Kensington Gardens to celebrate designing the Jubilee stamp for George V

Odds were heavily stacked against Barnett Freedman becoming a professional artist. Born in 1901 to a poor Jewish couple, living at 79 Lower Chapman St, Stepney, who had emigrated to the East End of London from Russia, Barnett’s childhood was scarred by ill-health and he was confined to bed between the ages of nine and thirteen. Yet he educated himself, learning to read, write, play music, draw and paint, all within a hospital ward. His nephew, Norman, recalled that “He played the violin for the king,” but that “When he acquired a bicycle his mother cut off the tyres as she considered it too dangerous for her son to ride.”

By sixteen, Barnett was earning his living as a draughtsman to a monumental mason for a few shillings a week. He made the best of this unexciting work in the day, spending his evenings at St Martin’s School of Art for five years from 1917. Eventually, he moved to an architect’s office, working up his employer’s rough sketches and, during a surge of war memorial work, honing his skills as a lettering artist.

For three successive years, Barnett failed to win a London County Council Senior Scholarship in Art that would enable him to study full time at the Royal College of Art under the direction of William Rothenstein. Finally, Barnett presented a portfolio of work to Rothenstein in person. Impressed, he put Barnett’s case to the London County Council Chief Inspector himself and a stipend of £120 a year was made, enabling Barnett to begin his studies in 1922. Under the direction of Rothenstein, Barnett’s talent flourished, taught by such fine draughtsmen as Randolph Schwabe and stimulated by fellow students Edward Bawden, Raymond Coxon, Henry Moore, Vivian Pitchforth and John Tunnard. Eight years after his entry, Rothenstein took Barnett onto the staff.

Although he could be prickly and even alarming on occasion, Barnett was revered by his former students. My late friends Leonard Appelbee and his wife Frances Macdonald, both artists, never stopped talking of his kindness. Burly Leonard used to help lift Barnett’s heavy lithographic stones when they were too much for the artist to manage alone, and when once Leonard and Frances considered moving to Hampstead, Barnett retorted – “You don’t want to go there. It’s an ‘orrible place!” According to Professor Rogerson, “He was a volatile character who did not respect authority and was always at war with the civil servants … yet I know people who were taught by him who say he was a very careful and punctilious teacher who paid a lot of attention to his students – though he could fire off if he was angry. At heart, I think he pretended to be a harsh kind of person but he was very good to a lot of people.”

After leaving the Royal College in 1925, Barnett had his share of problems. He painted prolifically but sold little – with his work only gradually being bought by collectors, although the Victoria and Albert Museum and Contemporary Art Society eventually bought drawings. In 1929, ill-health prevented him from working for a year. In 1930, he married Claudia Guercio whom he had met at art school, born in Lancashire of Sicilian ancestry. She also became a fine illustrator. Their son Vincent recalls that the home they created “was a warm place, vibrant with sound and brilliant colours, excitement darting from the music at night, the pictures on the walls, and the constant talking.”

Barnett enjoyed a long association with Faber and Faber, and his colour lithography and black-and-white illustrations for Siegfried Sassoon’s ‘Memoirs of an Infantry Officer,’ published in 1931, are outstanding. Works by the Brontë sisters, Walter de la Mare, Charles Dickens, Edith Sitwell, William Shakespeare and Leo Tolstoy benefited from his inspired illustration. Barnett believed that “the art of book illustration is native to this country … for the British are a literary nation.” He argued that “however good a descriptive text might be, illustrations which go with the writings add reality and significance to our understanding of the scene, for all becomes more vivid to us, and we can, with ease, conjure up the exact environment – it all stands clearly before us.”

He was also an outstanding commercial designer, producing a huge output of work for clients including Ealing Films, the General Post Office, Curwen Press, Shell-Mex and British Petroleum, Josiah Wedgwood and London Transport. The series of forty lithographs by notable artists for Lyons’ teashops was supervised by Barnett, including his famous and beautiful auto-lithographs ‘People’ and ‘The Window Box.’ Barnett wrote and broadcast on lithography and other aspects of art, with surviving scripts showing him to have been a natural talent at the microphone. When artists were being chosen for the series ‘English Masters of Black-and-White’ just after the Second World War, the editor, Graham Reynolds included Barnett among an illustrious band alongside George Cruikshank, Sir John Tenniel and Rex Whistler.

Barnett joined that select group who served as Official War Artists. Along with Edward Ardizzone and Edward Bawden, he accompanied the expeditionary force in the spring of 1940, before the retreat at Dunkirk, yet Barnett did not shed his iconoclasm and outspokenness when he donned khaki. Asked if he would paint a portrait of the legendary General Gort, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Barnett’s response was, “I am not interested in uniform … Oh well, perhaps I might if he’s got a good head?” On his return, Barnett continued to produce vivid, powerful pictures for the War Office and the Admiralty, gaining a CBE in 1946. But despite hobnobbing with military luminaries, Barnett never became posh, retaining his East End manner of speaking. Vincent Freeman recalls how Barnett once hailed a taxi-cab, “‘to the Athenaeum Club’, to which the incredulous driver retorted – ‘What, YOU?'”

After hostilities, Barnett remained busy with many commissions until in 1958, when he died peacefully in his chair at his Cornwall Gardens studio, near Gloucester Rd, aged only fifty-seven. Vincent recalls his final memory of his father, “discussing a pleasant lunch he had enjoyed with the family’s oldest friend [the artist] Anne Spalding.” Barnett was widely obituarized and his work was given an Arts Council memorial exhibition and tour. Subsequently, exhibitions such as that at Manchester Polytechnic Library in 1990 and new books have periodically enhanced his reputation.

Barnett Freedman is among my top candidates for a blue plaque, as one of the most distinguished British artists to emerge from the East End. There was a 2006 campaign to get him one in at 25 Stanhope St, off the Euston Rd, where he lived early in his career, but English Heritage rejected him, along with four others as of “insufficient stature or historical significance” – an unjust decision exposed by the Camden New Journal. The artist and Camden resident David Gentleman was one among many who supported the plaque, writing “He was a very good and original artist whose work deserves to be remembered. He influenced me in the sense of his meticulous workmanship. He was a real master of it.”

Professor Ian Rogerson, author of ‘The Graphic Work of Barnett Freedman’, considers Barnett “the world’s best auto-lithographer … A lot of people who do not seem to have contributed as much to the arts have managed to get blue plaques. Freedman’s work is being increasingly collected – and he is being recognised more and more as a major contributor to British art.” Of Barnett’s remarkable output, his son Vincent says – “A huge optimism and compassion shows itself to me in all his work and life. Humanity was his central driving force.”

Freedman family portrait with Barnett standing far left.

Barnett painting on the roof top as a war artist

Barnett shows his wife Claudia a mural he painted as the official Royal Marines artist.

Recording the BBC ‘Sight & Sound’ programme ‘Artists v Poets’ in February 1939, Sir Kenneth Clark master of ceremonies with scorer. Artists from left: Duncan Grant, Brynhild Parker, Barnett Freedman, Nicolas Bentley, and poets – W. J. Turner, Stephen Spender, Winifred Holmes and George Barker.

Barnett enjoys a successful afternoon fishing at Thame, Buckinghamshire, in the thirties.

Designs for the ‘London Ballet.’ (courtesy Fleece Press)

The Window Box, lithograph.

Advertisement for London Transport from the nineteen thirties.

Advertisement for the General Post Office rom the nineteen-forties.

Advertisement for Shell at the time of the Festival of Britain, 1951.

Design for Ealing Studios.

Cover for ‘Memoirs of a an Infantry Officer,’ Faber and Faber.

Cover for Walter de la Mare’s 75th Birthday Tribute, Faber and Faber.

Barnett Freedman’s ‘Claudia’ typeface.

Design for Dartington Hall, Devon.

Lithographs for ‘Oliver Twist,’ published by the Heritage Press in New York, 1939.

Barnett Freedman works courtesy Special Collections, Manchester Metropolitan University

You may also like to read David Buckman’s other features

From Bow to Biennale: Artists of the East London Group by David Buckman can be ordered direct from the publisher Francis Boutle and copies are on sale in bookshops including Brick Lane Bookshop, Broadway Books, Newham Bookshop, Stoke Newington Bookshop, London Review Bookshop, Town House, Daunt Books, Foyles, Hatchards and Tate Bookshop.

Simon Mooney at the Repton Boxing Club

Contributing Photographer Simon Mooney sent this dynamic photoessay of the life of the Repton Boxing Club in Cheshire St, taken at a recent training session when we went along to interview Club Chairman David Robinson.

“I’d walked past and seen the sign, and I knew the popular history,” admitted Simon, “but what makes it for me are the people who are there. They are all serious athletes, from the young ones in training to the old timers coaching them, who were once great boxers. And what you are looking to capture are their moments of interaction, because that is what it is about – the teaching.”

photographs copyright © Simon Mooney

You may also like to read these other boxing stories

David Robinson, Chairman of the Repton Boxing Club

Tony Burns, Coach at the Repton Boxing Club

Ron Cooper, Lightweight Champion Boxer

Sammy McCarthy, Flyweight Champion

Sylvester Mittee, Welterweight Champion

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round One)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Two)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Three)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Four)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Five)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Six)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Seven)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Eight)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Nine)

John Claridge’s Boxers (Round Ten)

J.W.Stutter Ltd, Cutlers

Bryan Stutter brandishes his Stutter scissors

Bryan Stutter and his wife Sue have amassed a handsome collection of old cutlery, all incised with the name of J.W.Stutter – the company founded by Brian’s great-great-great-grandfather Joel at the boundary of the City of London in the eighteen twenties. Cutlers were one of the myriad small trades that thrived here for centuries, selling their wares for domestic use and also providing tools to other manufacturers based in the vicinity, yet today the only evidence of their presence is in the name of Cutler St, a narrow thoroughfare leading off Houndsditch.

In an idle moment, seven years ago, Bryan was searching for the name of his forebear upon the internet when he found a J.W.Stutter cabbage knife for sale on an auction site. Bryan bought it on impulse and began searching for more items with the J.W.Stutter name, and thus his magnificent collection was born – reversing the trend of time, by bringing back together as many of the items manufactured and sold by J.W. Stutter as possible.

Bryan’s grandfather was the last in the family business and Bryan remembers coming up from Palmers Green as a child to Bishopsgate with his father to visit the shop in 1955 and seeing the famous 365 blade pen knife that was displayed in the window. “He offered sixpence to anyone that could open and shut every blade without cutting themselves,” Bryan recalled fondly. Originally, the company were manufacturing cutlers employing a sheet metal worker, a carpenter, an ivory carver and a silversmith, but by the sixties they could no longer compete with imported cutlery and the business was sold, moving to Hackney, only to close finally in 1982.

“As you get older, you start remembering things and you become interested in history, but by then the people you could have asked have died,” admitted Bryan, who had all but forgotten the former family business until he found some of the company papers with his father’s will. “I just thought, ‘this is my family history,'” he continued, gesturing to his proud assemblage of cutlery that includes the set of dessert knives he and Sue received as their wedding present, “If my daughter or nephew wants it, I can pass it in to them, and if nobody wants it, it can all go back on sale on the internet…”

J.W Stutter in Bishopsgate in the mid-twentieth century, with the 365 blade penknife on display.

365 blade penknife produced as an apprentice piece and shown at the Great Exhibition. Bryan remembers this in his grandfather’s shop.

J.W.Stutter at 133 Bishopsgate in 1911.

J.W.Stutter (third shop on the left) at 184 Shoreditch High St.

The nineteenth century cabbage knife that started Bryan’s collection.

Detail of the cabbage knife.

Hip flask by J.W.Stutter

Detail of the hip flask.

J.W.Stutter Corn knife c. 1840

Herb Chopper

Victorian pewter teapot

Detail of the pewter teapot

Sewing scissors, c. 1890

Nineteenth century razors in a presentation case.

Cobblers’ tool.

Detail of the cobblers’ tool

Victorian tackle retriever.

Set of dessert knives, mid-twentieth century.

Detail of the dessert knives.

Bryan & Sue Stutter with items from their Stutter collection.

Jack Corbett, London’s Oldest Fireman

Jack Corbett, born 1910

“I like the life of a fireman,” boasted Jack Corbett, who is London’s oldest surviving fireman at one hundred and two years old. Based at Clerkenwell Fire Station for the duration of World War II, Jack and his team were fortunate enough to endure the onslaught of the London Blitz without any fatalities. “It was all coincidental because I happened to live within a mile of the station,” he announced dismissively, as if he just fell into it. Yet the same tenacious spirit that sustained him through the bombing has also endowed him with exceptional longevity. “You want to go on living,” was what Jack told himself in the midst of the chaos.

“It’s not easy remembering what you did and didn’t do.” he confessed to me vaguely, casting his mind back over more than a century of personal experiences, “It all seems so bitty trying to put it all together, but it all went like clockwork. It was rather wonderful really.” Jack’s father was in the First World War and, after Jack witnessed the Second World War in London, he cannot escape disappointment now at the persistence of warfare. “It’s a shame after what we went through that people have learnt nothing,” he confided to me in regret. The threatened closure of Clerkenwell Fire Station, the oldest in Britain, meets with his disapproval too, “Modern life demands the police, fire service and ambulance yet, if you cut them, the longer it will take for these services to be applied – and that’s foolhardy.” he said, “Clerkenwell Fire Station is well-situated, in one direction is Kings Cross and in the other direction is the City of London.”

In wartime, as one of the firemen responsible for protecting St Paul’s Cathedral from falling bombs, Jack was given access to the entire structure and once he climbed up alone inside the gold cross upon the very top of the dome. Standing in that enclosed space so high over the city, with a single round glass panel to look out at either end of the cross-piece, was an experience of religious intensity for Jack. And now, at such a venerable age he is able to look back on his own life from an equally elevated perspective through time. “I don’t know what people think of me but I guess I’m a little on the starchy side. I try to be a man of principle but it’s not easy.” he admitted to me with a shy grin, “I don’t drink, I don’t smoke and I’ve always been a Christian.”

In 2000, Jack retired from London to live with his daughter Pamela in Maldon in an old house up above the river, surrounded by a luxuriant well-kept garden.”My parents were ordinary people but they produced a good commodity in me – my mother lived to ninety-three and my father to ninety-one.” he assured me in satisfaction, as we sat together admiring the herbaceous border from the comfort of his private sitting room. “Some people would have written their life, but I’m not that type. I’m not bothered,” Jack whispered, thinking out loud for my benefit – however, for the sake of the rest of us, I present this account of his story.

“When I left school at fourteen in Woking, I got a job as a guard boy. It was my first proper job, working for a gentleman. But in the thirties there was a financial crisis and quite a lot of people lost their property. So he said to me, ‘I’ll have to let you go.’ I didn’t realise it was the sack. Then, one wet day, I drove him to Woking Station and he said, ‘You probably realise I’ve got a business in London. Would you like to change your job?’ The business was a glass warehouse in Clerkenwell, Pugh Bros off St John St.

Isn’t it strange? I can’t remember the name of the man who gave me my job and brought me up from my lowly life in Woking to London, where I met my wife, and the story of my life proper began there.

I lived at 330 St John St, from my early twenties, when I first came to London and that’s where I met my wife Ivy. I was the lodger and she was the only daughter of the house, and we went to Sadlers’ Wells Theatre for our first date and we got married in 1935 in the Mission Church in Clerkenwell. She worked at a furrier and she was pregnant with our daughter Pamela when the war started. I was keen to get behind an ack-ack gun, but she reminded me I could get assigned anywhere and not to be so quick. My daughter was due in April 1939, not the best time to be born because of the situation with the war, but my baby, my wife and mother-in-law were evacuated to Woking where I had my original home, so that was alright. They couldn’t come back to London – they wanted to but I explained that bombs were dropping.

When I was enlisted, I joined the City of London Auxiliary Fire Service. They trained you up to a certain level but after the London Fire Brigade lost a lot of their men who were ex-army and ex-navy, when they were called back to the forces, they needed to replace them and I was accepted. So eventually I became a professional. We were always on duty, it was continuous duty during the Blitz, then they granted you four hours break, not every day but when circumstances allowed. Clerkenwell was one of eighty fire stations, so you can imagine the immensity of it. In London, there was a separate water system for the fire service but when that became broken, we had to pump water from the Thames.

I never thought about the danger – I just got on with it, like everybody else. You’d be a strange person if you didn’t know fear but in any situation, you go in and do your duty to the letter. Often, what I found exciting was that you didn’t know what kind of fire you were going to. The job consisted of extinguishing the fire and rescuing life, and rescuing life was the most important because a building can be rebuilt – your priority was saving lives.

We were being bombed in the docks where all the food storage was, so we had a job there and ,when we had to go further downstream to extinguish the oil depot, we had to go through the East End where there were lots of houses on fire, and they used to call us names. Once, we heard a group of five bombs approaching Clerkenwell and I thought one must surely be for us, but it hit the building next door. We couldn’t see inside the fire station for the dust and I really thought that one had my name on it.

When things were cooling off, you could take a weekend and I went down to Woking to see my family. Eventually when things quietened, my wife found a house in Finchley and that’s where we had our son and lived for the next sixty years and where my wife died twelve years ago. We’d been married sixty-seven years. We had a grand life if you come to think of it. I wonder what would have happened without the war – I would have continued working at the glassworks. I was moving up, after three years I was appointed manager of the guys who were going out making deliveries of glass.

After the war, I asked for a transfer nearer home, and they transferred me to Hornsey and I stayed in the fire service until 1965. The average person wanted to get back to ordinary life, but there’d been so much change it wasn’t that easy. You want to go on living and when you have two children, they want to have a life. Now I have eight great-grandchildren, it has all grown like a tree of life from Pamela’s mother.”

Jack Corbett – “I don’t know what people think of me but I guess I’m a little on the starchy side.”

Jack with Freda and Cousin Dot, 1923

Charles Corbett, Jack’s father

Charles and Ann Corbett, 1944

330 St John St where Jack lived when he came to London and met his wife Ivy. Ivy’s parents lived on the ground floor, and Jack and Ivy lived on the first floor after they married.

Jack aged twenty, 1930

Jack in his first car.

Jack and Ivy, 1934

Jack and Ivy’s marriage at Clerkenwell Mission Chapel, 18th May 1934

Jack (on the far left) joined the City of London Auxiliary Fire Service, 1939

Jack (with his back to the camera) pictured fighting a fire at St Bartholomew’s Hospital during the London Blitz.

High Jinks with the Metropolitan Fire Brigade, 1955

Jack returns to Clerkenwell Fire Station, January 2013

Jack with Green Watch at Clerkenwell Fire Station

Jack in his garden in Maldon, aged one hundred and two.

Jack and his daughter Pam

Clerkenwell Fire Station, Britain’s oldest working fire station.

Photograph of Clerkenwell Fire Station copyright © Colin O’Brien

You may also like to read about

More Crowden & Keeves’ Hardware

More magnificent hardware from the 1930 Crowden & Keeves catalogue in the possession of Richard Ince proprietor of James Ince & Sons, Britain’s oldest umbrella manufacturers, which Richard tells me has been knocking around his factory for as long as he could remember. Operating from premises in Calvert Avenue and Boundary St, Crowden & Keeves were one of the last great hardware suppliers in the East End, yet the quality of their products was such that items may still be discovered in use around the neighbourhood today.

You may also like to take a look at the first selection of

and these other hardware & ironmongery stories

Allen & Hanburys’ Surgical Appliances

At London’s Oldest Ironmongers

Robert Senecal of 37 Spital Sq

Claudia Hussain with a portrait of Robert Senecal, her great-great-grandfather, at 37 Spital Sq

37 Spital Sq is the last eighteenth-century house standing in what was once a fine square lined with similar buildings. Constructed upon the wealth of the silk industry that sustained Spitalfields for two centuries, it is an enigmatic reminder of that vanished world. Yet Claudia Hussain, the great-great-granddaughter of Robert Senecal, a silk manufacturer, came recently to 37 Spital Sq with photographs of her ancestors, revealing the faces of those who, more than a century ago, inhabited these panelled rooms which today house the offices of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.

“We always knew our ancestors were Weavers,” admitted Claudia, “but my Aunt Dot corrected me, saying they were Silk Manufacturers.” Although Claudia’s great aunt died years ago, she had drawn a family tree that began with Peter Senecal, a Huguenot Weaver who came to Spitalfields in 1747, and she had annotated the family album, and left a written account of her ancestry too. Imagine Claudia’s surprise when she returned to Spital Sq out of curiosity last year and discovered that her great-great-grandfather’s house was still standing.

Recently, Claudia brought three heavily-bound albums containing the portraits of the former inhabitants of 37 Spital Sq to show me and it was a poignant experience to contemplate their faces as we sat in the old house they had known so well. These are the pictures of the last generation to be involved in silk manufacturing, the trade that had occupied the family for centuries until Robert Senecal oversaw the demise of the industry in the eighteen-eighties and closed the business. There are four portraits of him – dated between 1882, when he was still a Silk Manufacturer employing forty hands (as recorded in the census of 1881), and 1895 when he died at fifty-six, after relinquishing the trade and moving to Stoke Newington.

Robert was a handsome man with bold features and a confident nose, yet his short-sighted gaze peers out anxiously from eyes that became increasingly lined as time and mortality overcame him in his last years, when he was forced to sell up, witnessing the death of an industry which had defined the identity of his family for as long as he knew. There was a residual youthful fullness to his visage, at forty-five years old in 1881, that faded out to be replaced by the features of an old man in the final picture. Only his favourite jacket with its braided binding remained constant, even if it grew a little worn and, perhaps, was replaced with another cut to fit a fuller figure.

Claudia’s great aunt was Robert Senecal’s grand-daughter and, according to her history, he took over the business from his father who was also called Robert – “Robert & Ann Senecal lived at 37 Spital Sq and when he died his son Robert & Rosabel came from Hanbury St to live there. I do not know if my grandparents met through visiting when silk weaving was carried on, but by then work was taken out and done by the weavers in their homes. Later, owing to ‘Free Trade,’ my grandfather sold the business. They [my grandparents] told me of their childhood when there were at least five hundred master weavers in Spital Sq and thousands of people in the surrounding neighbourhood thus employed. Quilt weavers trundled their quaint machines through the streets after the fashion of tinkers and their familiar cry brought weavers hurrying from their houses with work to be done on the spot.”

Old Bailey records reveal Robert’s father as a silk winder living in Nicholl St, Bethnal Green, in 1833, when he had two rabbits stolen by an eighteen-year-old who sold them to a pork butcher at 8 Brick Lane, for which the youth was imprisoned for three months. The previous year, Robert’s father was knocked down and robbed in Pelham St (now Woodseer St) of his gold watch – while returning from a night out at The White Horse, Bethnal Green – by a twenty-four-year-old who was sentenced to death with a plea of mercy on account of good character. On this occasion, Senecal described himself as a silk cane spreader of Sclater St. Evidently, he prospered in his trade in the following decades to ascend to the ownership of 37 Spital Sq, at the centre of Spitalfields silk industry.

One other Senecal has stepped from the shadows, that of Robert Senecal’s son Harry Lawrence, a commercial traveller employed in Commercial St, who was convicted in 1891 of “administering noxious drugs to May Robson with intent to procure an abortion.” He and May Robson had lived together as a couple in Brighton, but he professed he was unable to marry until his father died. The child was stillborn and Harry emigrated to America in 1893 (two years before his father died), where he married Mina Van Winkle from Iowa and lived in Denver until 1943. It is not unlikely that Harry’s behaviour added a few more lines to his father’s troubled brow.

So far, Claudia’s research has revealed only these sparse tantalising facts about her antecedents from 37 Spital Sq, yet visiting the house they inhabited was an experience of a different calibre. “Very exciting and slightly surreal” was Claudia’s verdict on the day.

This was the door where Robert Senecal once walked in.

The census of 1881 lists Robert Senecal of 37 Spital Sq, Silk Manufacturer employing forty hands, born in the Old Artillery Ground, Spitalfields (click image to enlarge)

Robert Senecal, Silk Manufacturer, 7th May 1838 – 7th April 1895

Rosabel Senecal, 16th January 1840 – 29th July 1908

Harry Lawrence Senecal, Commercial Traveller, born 17th January 1867 – emigrated to America, arrived at Ellis Island April 6th 1893, and died in Denver in 1943.

Rosabel Ann Senecal, born 1865 – married Joseph Daniels of Stamford Hill and bore fourteen children.

Robert John Senecal Jr, Builder’s Timekeeper. 20th June 19862 – 25th November 1928

The Senecals visited W.Wright for their portraits when they lived in Spital Sq..

Rosabel Senecal

Robert Senecal

Rosabel Senecal

The last portrait of Robert Senecal.

The last portrait of Rosabel Senecal.

The Senecals had their photographs taken by Augustus W. Wilson & Co when they moved to Stoke Newington.

Robert Senecal’s tomb in Abney Park Cemetery is on the far right.

The monument to Robert Senecal and his clan today – the urn has been replaced by a cross.

37 Spital Sq today

You may also like to read about