Gustave Doré’s East End

I have been thinking about Gustave Doré lately, as the freezing miasma of winter descends upon the city and I struggle to negotiate the excited crowds thronging in the busy streets. Gazing upon the teeming masses in the flickering half-light outside Liverpool St Station, I see his world where deep shadows recede into infinite gloom and I succumb to its terrible beauty.

Doré signed a contract to spend three months in London each year for five years and the completed book of one hundred and eighty engravings with text by Blanchard Jerrold was published in 1872, entitled London – A Pilgrimage. Although he illustrated life in the West End and as well as in the East End, it is Doré’s images of the East End that have always drawn the most attention with their overwhelming sense of diabolic horror and epic drama, in which his figures drift like spectres coalesced from the ether.

In Bishopsgate

In Wentworth St, Spitalfields

Riverside St

In Bluegate Fields

A City Thoroughfare

Inside the Docks

In Houndsditch

Turn Him Out, Ratcliff

Warehousing in the City

Billingsgate Early Morning

Off Billingsgate

Refuge – Applying For Admittance

Brewer’s Men

Hay Boats On The Thames

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

Wapping Stairs

Wapping Old Stairs

I need to keep reminding myself of the river. Rarely a week goes by without some purpose to go down there but, if no such reason occurs, I often take a walk simply to pay my respects to the Thames. Even as you descend from the Highway into Wapping, you sense a change of atmosphere when you enter the former marshlands that remain susceptible to fog and mist on winter mornings. Yet the river does not declare itself at first, on account of the long wall of old warehouses that line the shore, blocking the view of the water from Wapping High St.

The feeling here is like being offstage in a great theatre and walking in the shadowy wing space while the bright lights and main events take place nearby. Fortunately, there are alleys leading between the tall warehouses which deliver you to the waterfront staircases where you may gaze upon the vast spectacle of the Thames, like an interloper in the backstage peeping round the scenery at the action. There is a compelling magnetism drawing you down these dark passages, without ever knowing precisely what you will find, since the water level rises and falls by seven metres every day – you may equally discover waves lapping at the foot of the stairs or you may descend onto an expansive beach.

These were once Watermen’s Stairs, where passengers might get picked up or dropped off, seeking transport across or along the Thames. Just as taxi drivers of contemporary London learn the Knowledge, Watermen once knew the all the names and order of the hundreds of stairs that lined the banks of the Thames, of which only a handful survive today.

Arriving in Wapping by crossing the bridge in Old Gravel Lane, I come first to the Prospect of Whitby where a narrow passage to the right leads to Pelican Stairs. Centuries ago, the Prospect was known as the Pelican, giving its name to the stairs which have retained their name irrespective of the changing identity of the pub. These worn stone steps connect to a slippery wooden stair leading to wide beach at low tide where you may enjoy impressive views towards the Isle of Dogs.

West of here is New Crane Stairs and then, at the side of Wapping Station, another passage leads you to Wapping Dock Stairs. Further down the High St, opposite the entrance to Brewhouse Lane, is a passageway leading to a fiercely-guarded pier, known as King Henry’s Stairs – though John Roque’s map of 1746 labels this as the notorious Execution Dock Stairs. Continue west and round the side of the river police station, you discover Wapping Police Stairs in a strategic state of disrepair and beyond, in the park, is Wapping New Stairs.

It is a curious pilgrimage, but when you visit each of these stairs you are visiting another time – when these were the main entry and exit points into Wapping. The highlight is undoubtedly Wapping Old Stairs with its magnificently weathered stone staircase abutting the Town of Ramsgate and offering magnificent views to Tower Bridge from the beach. If you are walking further towards the Tower, Aldermans’ Stairs is worth venturing at low tide when a fragment of ancient stone causeway is revealed, permitting passengers to embark and disembark from vessels without wading through Thames mud.

Pelican Stairs

Pelican Stairs at night

View into the Prospect of Whitby from Pelican Stairs

New Crane Stairs

Wapping Dock Stairs

Execution Dock Stairs, now known as King Henry’s Stairs

Entrance to Wapping Police Stairs

Wapping Police Stairs

Metropolitan Police Service Warning: These stairs are unsafe!

Wapping New Stairs with Rotherithe Church in the distance

Light in Wapping High St

Wapping Pier Head

Entrance to Wapping Old Stairs

Wapping Old Stairs

Passageway to Wapping Old Stairs at night

Aldermans’ Stairs, St Katharine’s Way

You may also like to read about

Madge Darby, Historian of Wapping

Whistler in Wapping & Limehouse

Upon The Subject Of Horace Warner’s Spitalfields Nippers

Today it is my pleasure to publish the text of my introduction to the definitive collection of Horace Warner’s photographs of the Spitalfields Nippers that we launched in November

There is a rare clarity of vision in the photography of Horace Warner that brings us startlingly close to the Londoners of the turn of the nineteenth century and permits us to look them in the eye, as if for the very first time.

Geographically, his Nippers were creatures of the byways, alleys and yards that laced Spitalfields. Imaginatively, theirs was a discrete society independent of adults in which they were resourceful and sufficient, doing washing, chopping wood, nursing babies and making money by selling news- papers and hawking flowers, or bunching parsley for market.

A few swaggered for the camera, but most were preoccupied in their own all- consuming world, and look askance at us without assuming the playful, clownish faces that adults expect of children today. These Nippers were not trained to fawn by innumerable snaps, and consequently many have a presence and authority beyond our expectation of their years.

Horace came to Spitalfields at the end of the nineteenth century as superintendent of the Sunday School at the Bedford Institute, one of nine Quaker Missions that operated in the East End of London. Years later, in 1913, the Institute paid two pounds, fifteen shillings and sixpence for around twenty photographs he had taken of the children, for use in their fund-raising activities, reproducing them in handbills and upon collecting boxes.

These pictures were selected from a significantly larger body of photography that Horace created at that time and gathered into two albums, which passed from the hands of his wife Florence into the possession of his elder daughter Gwen after his death and, subsequently, to his grandson Ian Warner McGilvray. For more than a century, this collection of images was hardly been seen by anyone outside his family until the current publication, in which they are reunited with those pictures purchased by the Bedford Institute – permitting a full assessment of Horace’s photographic achievement.

Although his subjects were some of the poorest people in London, Horace’s compassionate portraits exist in sharp contrast to the familiar stereotypical images created by some social campaigners of his era, who commonly portrayed children solely as victims of their economic circumstance and sometimes degraded them further by the act of photography itself. Characteristically, Horace granted his subjects the dignity of self-possession and, as a consequence, they present themselves to his lens on their own terms, whether overtly playing to the camera or retaining a composed equanimity.

Born into a family of Quakers – members of the Religious Society of Friends, almost since the inception of the movement – Horace and his brother Marcus worked in the family business of Jeffrey & Co run by their father Metford Warner (1843–1930), which operated from a factory in the Essex Rd just a short walk from the family home at Aberdeen Park in Highbury. Horace’s father invented a means to print wallpaper without the use of arsenic and was committed to representing artists’ designs more accurately than had been done before. He was an idealist and his collaborations with William Morris, William Burges and Walter Crane, and other leading designers, made Jeffrey & Co one of the top manufacturers in Britain, winning national and international awards. Most famously, William Morris’ wallpaper designs were printed at the factory in Islington from 1864 until 1940, and Metford continued to direct the company with Horace and Marcus until 1930, when Jeffery & Co was taken over by Arthur Sanderson.

A few miles down the road in Spitalfields, the Bedford Institute owed its origin to a revival of Quakerism encouraged by Peter Bedford (1780–1864), a philanthropist silk merchant who devoted himself to alleviating poor social conditions. Rebuilt in 1893, the handsome red brick Bedford House that stands today upon the corner of Quaker St would have been familiar to Horace and the urban landscape he knew is still recognisable, even if the dwellings of the courtyards and narrow streets where he took his photographs are long gone.

When the Eastern Counties Railway came through in the eighteen-thirties, hundreds of families were pushed from their homes, filling the surrounding streets. The overcrowded area to the north became known as the Nichol, notorious for criminality, while the tragedy of a soldier’s widow living in one room with her nine children in Poole’s Place, south of Quaker St, was selected in 1844 by Frederick Engels in ‘The Condition of The Working Class in England’ as indicative of the suffering in London.

This area to the south of the Bishopsgate Goodsyard had been built up in the eighteenth century when the silk industry thrived in Spitalfields and before the decline of the native trade, through competition from imported goods, that led to the neglect of these buildings which were subdivided and rented out at one family per room.

When Charles Booth made his assessment in 1889 for the ‘Descriptive Map of London Poverty,’ he coloured a few of the wider streets as pink, meaning “Fairly comfortable. Good ordinary earning.” Most of the habitations in the yards behind those streets were coloured pale or dark blue, meaning “Poor. 18s. to 21s. a week for moderate family.” or “Very poor, casual. Chronic want.” But the narrow streets and alleys at the core of this crowded neighbourhood were coloured black, indicative to Booth of the presence of the “Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal.”

It was these people, living in the shadow of the Bishopsgate Goodsyard and almost upon the doorstep of the Bedford Institute, that Horace befriended and photographed. At the core of this district was a narrow triangle of shabby dwellings circumscribed by roads and huge buildings upon three sides, but no more than five hundred yards across. It was bordered to the east by Truman’s Brewery and to the west by Commercial St, cut through in the eighteen-fifties to carry traffic from the London Docks to the Eastern Counties Railway Terminus in Bishopsgate. To the south lay the Spitalfields Fruit and Vegetable Market and, in between, the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties, with a capacity of two thousand, where Charlie Chaplin performed at ten years old as one of the Eight Lancashire Lads in 1899 and,also at ten years old, Bud Flanagan became a call boy in 1906, delivering fish and chips to the performers from his father’s shop in Hanbury St.

The dramatic tension in many of the photographs in the Spitalfields albums stems from the clear-eyed tenderness with which Horace portrayed the children, combined with an equally unflinching record of their poor living conditions. There is sometimes a disquieting irony in these gleefully unselfconscious images of children in rags with skinny limbs and dirty feet and hands, when they appear unaware of their own poverty and inhabit their existence as the only life they know. In this way, the open demonstrations of joy and pride in these photographs subvert the common historical assumption that residents of the East End in the nineteenth century led lives of unqualified degradation.

Yet Horace’s daughter Gwen testified that it was his dismay at the squalor in the East End which prompted him to take pictures witnessing the lives of people there and, although Horace was foremost a portraitist, the detail of his photography reveals plenty about the precise nature of the culture and society his subjects inhabited.

The variety and individuality of clothing and textiles in these photographs belong to an age before the industrialised mass- production of clothes we know today. These garments went through many owners, handed down through the family, altered, patched and refashioned until they fell apart. For centuries, Spitalfields had been the centre of London’s textile industry and occasionally, such as in the three fine matching dresses worn by the Ellis sisters, children may have clothes that were designed and made by their mothers who were skilled workers in the garment trade. The ancient Houndsditch Rag Fair existed just a mile to the south, until it was closed permanently to prevent the spread of smallpox, and this may explain the presence of so many elaborately- detailed dresses in antique designs of the earlier nineteenth century, which could have been acquired cheaply in the market and cut down to size.

Although children commonly played outdoors in summer in bare feet, many of the Nippers lack footwear of any kind or have only worn-out boots with holes. The Bedford Institute collected old boots to distribute to the children and some of these pictures may record the arrival of these cherished acquisitions. Horace’s younger daughter, Ruth, recalled her father’s picture captioned “Little Adelaide’s Only Boots” upon the living room wall in her childhood alongside portraits of the Nippers, as a reminder of those less fortunate than she and her sister Gwen. Ruth accompanied Horace on trips to deliver Christmas presents to children in Quaker St in the nineteen twenties, and her memories of the time Horace spent arranging she and her sister in family photographs may reveal a hint of his photographic method.

In the background of several photos, costermongers’ barrows with elaborate carved lettering, indicating the makers who leased them, speak of the proximity of the Spitalfields Market, and the culture of hawking and street trading in the East End. In early summer, parsley season offered piecework – as illustrated in a sequence of pictures featuring the large baskets in which loose parsley arrived and children gathering round to bunch it up for sale.

James McBarron who grew up in Hoxton in the thirties explained to me the practice of wood-chopping for pennies illustrated in Spitalfields Nippers. “We kids chopped firewood to make money. The boys and girls used to go around collecting tea-chests and packing-boxes from the back of furniture factories, and say ‘Can we take it away, Mister?’ We chopped it up into sticks and made bundles, and we’d sell them for a penny or a ha-penny. We used to go to Spitalfields Market too and ask for ‘Any spunks?’ or ‘Spunky oranges and apples?’ and they’d chuck the fruit that was going bad to us.” This culture of foraging among the left-overs and spoilt produce in Spitalfields persisted until the wholesale fruit and vegetable market moved out in 1991 and it may explain the origin of the trophy cabbage that a boy clutches so proudly in one portrait photograph.

Children swarm in the streets in these pictures and in such large families, with both parents working long hours, it fell upon older children to take care of younger siblings and undertake household chores, as shown in the images of baby-minding, sweeping, window-cleaning and boiling-up laundry over fires in yards.

Similarly, children were left to devise their own entertainment, inventing games and pastimes by contriving swings and make- shift carts, drawing on walls and flagstones, playing dice and holding imaginary tea parties upon the pavement, and filling the yards with singing games such as ‘Sally Go Round the Moon,’ photographed by Horace and – according to Dan Jones the rhyme collector – still played in East End playgrounds today. Pets figure in these photographs too, cats, kittens, dogs and rabbits, and there is an un expected image of a boy tending his garden. This modest vernacular East End tradition of horticulture is commonly ascribed to the Huguenots, introducing flower-fancying and pigeon-fancying to Spitalfields in the seventeenth century. In Horace’s compelling portrait of the girl with a bird on her head, the pigeon is a fancy variety. These creatures were bred and housed in sheds in backyards and brought out each summer for racing and competitions, as they are still in some locations in Bethnal Green.

It is the photographs of the newspaper seller and the boys holding up news placards from June 1902, announcing the end of the Second Boer War, that give us the only precise date we have for any of these pictures. Elsewhere, there are round tin badges worn by a couple of children, with photographs of King Edward and Queen Alexandra at the centre, celebrating their Coronation in August 1902.

Horace’s daughter Gwen believed that some of his Spitalfields pictures were taken in the eighteen-nineties and a note in the front of of his albums suggests they were complete by 1905. Later, Horace wrote accompanying texts for a couple of his photographs, when they were published by the Bedford Institute in fund-raising leaflets in 1912, but the time lapse suggests this was their adopted use rather than his first intent in taking the pictures.Assuming the fictional alter-ego of the fairy ‘Silverwing’ as a whimsical device to engage his young middle-class readers, nevertheless he was insistent to assure them of the veracity of his personal observation. “The incidents here recounted are actual facts from the lives of some of the children living around the Bedford Institute, Quaker St, Spitalfields,” he wrote.

“The night was getting late and Silverwing must be back before dawn, but he flew along the road and alighted at the Spitalfields Market. All was still within, but outside in the gutter were a few cases of rotten oranges, and around those were gathered several children with their arms plunged elbow deep in the rotting fruit, feeling for an orange here and there that might be less rotten than the bulk within those cases. Other children were hunting amidst the market garbage for anything that might be of use at home.

Nigh by, another squalid street was guarded top and bottom by the public houses, and a passage way leading into it was likewise guarded by another, so that no-one could enter into the street without passing one, and halfway down the same stood another, with its temptation of warmth and light. A little court entrance, bearing no name over it, tempted Silverwing to go still further, so up the alley-way he went. This too, had its one gas lamp, beneath which a number of big boys were gambling round an inverted barrel, losing and gaining their hard-earned pence.

Still another staircase in the corner of the court tempted the fairy to go. The stairs were dark and irregular, and seemed to twist and turn until the first little landing was reached. A child was leaving a darkened room and Silverwing slipped in. Within sat a lad of ten nursing a baby until his mother had returned with the father from hawking toys in the gutter to help pay the night’s rent, and there were also two smaller brothers on the mattress behind the door. The grate lacked any fire, and the light again only from that of the chance gleam from the court gas lamp.”

In 1975, the photographs acquired the title ‘Spitalfields Nippers’ when the Bedford Institute published the pictures they bought in 1913 in a pamphlet to accompany a small exhibition that was subsequently displayed in the entrance to the Whitechapel Gallery. This was when Horace’s pictures were first seen by a wider audience that appreciated them for their photographic quality as well as for their social reportage.

Yet, as early as 1905, there had been an occasion when the pictures were shown to an influential group of people who recognised the power of Horace’s photography. Attached inside the cover of Horace’s first Spitalfields album is a piece of notepaper from the Warden’s Lodge at Toynbee Hall, dated June 21st 1905. The Hall had been established in 1884 by Samuel and Henrietta Barnett, as the first university settlement in the East End, in the hope that educational and social projects undertaken by students from Oxford and Cambridge encouraged a social conscience among future generations of political leaders.

“These photographs were taken by an Associate of Toynbee Hall who has lent them to Mrs Barnett for the use of Lord Crewe,” reads the text of the letter inscribed in a careful italic hand with an annotation at the top in red ink, “Returned with thanks, Crewe, 27th July.”Henrietta Barnett was committed to reforming the brutal regimes of Poor Law Schools and in 1896 she established the State Children’s Association “to obtain individual treatment for children under the Guardianship of the State.” Lord Crewe was one of several powerful aristocrats who chaired the SCA and it appears Horace’s Spitalfields albums were used as evidential material in their political campaign to secure social reforms for vulnerable children.

True to his belief in the social value of culture, Samuel Barnett also founded the Whitechapel Gallery round the corner from Toynbee Hall, that opened its doors in 1901, with a mixed show of contemporary work including a selection of pictures by Sir Edward Burne-Jones which Horace took the Nippers to see, leading them on an excursion beyond their familiar territory and photographing their first encounters with fine art.

Working in the family wallpaper business, Horace had the income and aesthetic training to explore photography in his spare time and produce images of the highest quality. As superintendent and trustee of the charitable Bedford Institute, he was brought into close contact over many years with the families who lived nearby in the yards and courts south of Quaker St, winning their trust and affection. As a Quaker, he believed in social equality and that the divine was in everyone, and he was disturbed by the suffering he encountered in the East End. In the Spitalfields Nippers, all these things came together for Horace as the result of a unique set of circumstances, allowing him the opportunity to create exceptional, humane images which gave dignity to his subjects and producing great photography that is without parallel in his era.

Horace took a self-portrait when he was around thirty years old, at the time he was photographing the Nippers, the pictures that establish his posthumous reputation as a photographer. If you look closely you can just see the bulb in his left hand to control the shutter, permitting him to capture this image of himself. With his pale moon-like face, straggly moustache and shiny locks, he looks younger than his years and yet there is an intensity in his concentration matched by the poised energy of his right arm. “There isn’t a great deal we know about Horace,” his grandson, Ian Warner McGilvray, admitted to me plainly, “and, in any case, I imagine he would probably have been quite content to have it that way.”

We know Horace through his photography, the record of his response to the Nippers and their response to him – permitting us to see them through his eyes. His Spitalfields Nippers are a unique set of photographs, that witness a particular time, a precise location, a specific society, and an entire lost world. Today there is nothing left of it but Horace’s photographs, yet – since he annotated many of them with the names of his subjects – we have been able to discover more about the lives of the Nippers in public records and publish the biographies that we have collated in the book.In Spitalfields at this time, one in five children did not survive until adulthood but our researches reveal that among the poorest families which Horace photographed, the mortality rate was closer to a third.

Shamefully, more than a century later, the London Borough of Tower Hamlets that contains the locations of the Spitalfields Nippers, has the highest rate of child poverty in Britain.

Thus Horace Warner’s photographs confront us with the nature of social progress, reminding us of the human value of the reforms enacted in the twentieth century that lifted up the lives of all in this country and emphasising the necessity of the struggle for a modern compassionate society which can protect its most vulnerable members.

Horace Warner (1871-1939)

Click here to order a copy of SPITALFIELDS NIPPERS by Horace Warner

You may also like to read about

Lizzie Flynn & Dollie Green by Horace Warner

Annie & Nellie Lyons by Horace Warner

Wakefield Sisters by Horace Warner

Graham Marshall, Spitalfields Crypt Trust

Graham Marshall

The name ‘Spitalfields’ refers to the Priory of St Mary Spital, situated on Bishopsgate where Spital Sq is today, that offered shelter to the dispossessed and homeless from 1197 until it was dissolved by Henry VIII in 1539. Yet the identity of Spitalfields as a place of refuge had been established and, to this day, this vital work goes on at the Spitalfields Crypt Trust. Originating as a shelter under the church, opened by Rector Dennis Downham in 1965, the endeavour acquired its own dedicated building in the corner of Shoreditch churchyard when Spitalfields was being renovated in the nineties .

The common thread through recent decades has been the benign presence of Graham Marshall, a modest man who began as a volunteer in the seventies and discovered his life’s work in the crypt, serving those who walked through the door. The policy was never just to offer shelter but to assist in finding the path to recovery. When Graham started, half of the residents were Scottish and half Irish, and the prevailing affliction was alcohol dependency, whereas these days the racial mix is more diverse and drug use is the major problem.

“It’s handholding all the way, because if you let go people will get lost,” Graham admitted to me, speaking from thirty years of experience, “It’s about getting them on to the next stage and sticking with them.”After thirty-seven years, Graham is now Director of the Trust, overseeing the running of the organisation yet still directly involved with everyone that comes through the door and aware of each individual’s needs and challenges.

The Trust runs four open sessions each week, either at St Leonard’s Church or the Tabernacle Centre, at which anyone in need can come for food and tea. Acorn House, at the corner of Calvert Avenue and Shoreditch High St replaces the crypt, provides accommodation for sixteen residents for up to a year, while the New Hanbury Project on the ground floor of this building offers educational activities, from literacy courses to basic IT skills and woodwork. “It’s about ‘What am I going to with myself?’,” Graham said simply, ‘It’s a place where people can start to make progress.” Beyond this, there are three long-term hostels where people can stay for three to four years, as they learn to live independently, and the Trust runs Paper & Cup Coffee Shop in Calvert Avenue and another in Bow, where residents can learn the skills of working with people and gain experience that will give them a chance of finding a job.

An individual of self-effacing temperament and single-minded determination, Graham has kept the Spitalfields Crypt Trust small with minimal bureaucracy, so that it can remain a flexible organisation focussed on its purpose, and financially independent, so that it can work in its own way without being subject to the whims of local authority funding. Above all, he has personally kept the project alive so that the quietly dignified work can continue, enabling hundreds of people to find a new existence away from the streets and free from the dependencies that blighted their lives.

“I volunteered for a year at the Spitalfields crypt in 1977 and stayed ever since. My first job was working at the front desk, giving people their sandwiches and clothing. They came down into a place in the crypt where they could take a shower and we would change their clothes.

I come from Folkestone. Like many young people, I experimented with drugs and got into trouble, and spent a few nights on the streets of London as a seventeen year old, but fortunately had a home to go back to. A couple of years later, I met a girl who was a Christian and I became a Christian, and then I went into rehab in Greenwich for a year. I did a lot of voluntary youth work and tried to get into YMCA college but failed, so then I went back to work in Spitalfields again as a volunteer.

From the start, I worked on the front desk and I loved it. After a year, they asked if I could stay on permanently, but I said, ‘I need to find a way to make some money.’ They said, ‘We are going to advertise for someone to do your job.’ So I thought, ‘Oh wow, I’d love to do that!’ and I got the job and the rest is history.

I love my work. I love every day, I don’t ever have a bad one. I see positive change. Some people think it’s depressing and it’s about failure and degradation, but it’s not – it’s about people coming off dependency and recovering their sobriety, and learning to love themselves.”

At the entrance to the crypt at Christ Church in the seventies

Domitory in the crypt

Dining room in the crypt

Recreation in the crypt

New Hanbury Project in Calvert Avenue

The yard between New Hanbury Project and St Leonard’s Churchyard

Portrait of Graham Marshall copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

Irene Stride Remembers Spitalfields

Wapping Tavern Tokens

I would dearly loved to have accompanied you on a pub crawl along the river and through the alehouses and stews of seventeenth century Wapping, but instead we must content ourselves with these few humble tavern tokens as the imaginative means to evoke an entire long-lost world.

King’s Head Taverne

… At The Hermitage

The Ship Taverne

… Wapping Wall, 1650, John Saunders

Bunch of Grapes, John Goddin, King’s …

… Streete At Wapping

Queen’s Head, New Crane Wharf ….

Queen’s Head, New Crane Wharf ….

Coffee, chocolat, tea, sherbet .… Can anyone decipher the rest?

At The White Bear

… At Wapping Wall

Edward Fish At …

… The Sunn In Wapin…

Roger Price At The…

… Black Boy In Wapin

At The Man In The …

.. Moun In Waping, 1652

.. Andrew Coleman At, His Halfpenny

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

The Gentle Author’s Wapping Pub Crawl

and these other tokens

At The Boar’s Head Parade

Contributing Photographer Colin O’Brien & I were greeted by Neil Hunt, Beadle of The Worshipful Company of Butchers, when we arrived at their Hall in St Bartholomew’s Close, Smithfield, yesterday to join a small crowd eagerly awaiting the annual appearance of the celebrated Boar’s Head in the first week of Advent, marking the beginning on the Christmas season in London.

This year sees the sixtieth anniversary of the revival of this arcane tradition which has its origin in 1343 when the Lord Mayor, John Hamond, granted the Butchers of the City of London use of a piece of land by the Fleet River, where they could slaughter and clean their beasts, for the token yearly payment of a Boar’s Head at Christmas.

To pass the time in the drizzle, the Beadle showed us his magnificent staff of office dating from 1716, upon which may be discerned a Boar’s Head. “Years ago, they had a robbery and this was the only thing that wasn’t stolen,” he confided to me helpfully, ” – it had a cover and the thieves mistook it for a mop.”

Before another word was spoken, a posse of members of the Butcher’s Company emerged triumphant from the Hall in blue robes and velvet hats, with a livid red Boar’s Head carried aloft at shoulder height, to the delighted applause of those waiting in the street. Behind us, drummers of the Royal Logistics Corps in red uniforms gathered and City of London Police motorcyclists in fluorescent garb lined up to receive instructions from Ian Kelly, the Master of the Company.

Everyone assembled to pose for official photographs with the perky red ears of the Boar sticking up above the crowd, providing the opportunity for a closer examination of this gloss-painted paper mache creation, sitting upon a base of Covent Garden grass and surrounded by plastic fruit. As recently as 1968, a real Boar’s Head was paraded but these days Health & Safety concerns about hygiene require the use of this colourful replica for ceremonial purposes.

The drummers set a brisk pace and before we knew it, the parade was off down Little Britain, preceded by the police motorcyclists halting the traffic. For a couple of minutes, the City stopped – astonished passengers leaned out of buses and taxis, and office workers reached for their phones to capture the moment. It made a fine spectacle advancing down Cheapside, past St Mary Le Bow, with the sound of drums echoing and reverberating off the tall buildings.

The rhythmic clamour accompanying the procession of men in their dark robes, with the Boar’s Head bobbing above, evoked the ancient drama of the City of London and, as they paraded through the gathering dusk towards the Mansion House looming in the east on that occluded December afternoon, I could not resist the feeling that they were marching through time as well as space.

Neil Hunt, Beadle of The Worshipful Company of Butchers

The Beadle’s staff dates from 1716

Leaving St Bartholomew’s Close

Advancing through Little Britain

Entering Cheapside

Passing St Mary Le Bow

In Cheapside

Approaching the Mansion House

The Boar’s Head arrives at the Mansion House

Photographs copyright © Colin O’Brien

You may also like to read about

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries Of London

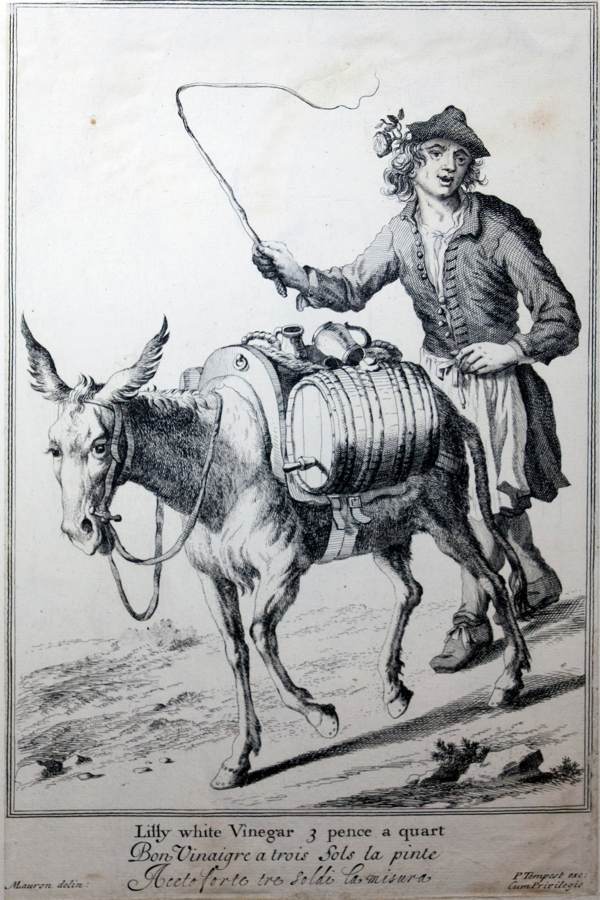

Today it is my pleasure to publish Marcellus Laroon’s vibrant series of engravings of the Cries of London reproduced from an original edition of 1687 in the collection at the Bishopsgate Institute

The death of Oliver Cromwell and the restoration of Charles II made the thoroughfares of London festive places once again, renewing the street life of the metropolis – and when the Great Fire of 1666 destroyed the shops and wiped out most of the markets, an unprecedented horde of hawkers flocked to the City from across the country to supply the needs of Londoners .

Samuel Pepys and Daniel Defoe both owned copies of Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London. Among the very first Cries to be credited to an individual artist, Laroon’s “Cryes of the City of London Drawne after the Life” were on a larger scale than had been attempted before, which allowed for more sophisticated use of composition and greater detail in costume. For the first time, hawkers were portrayed as individuals not merely representative stereotypes, each with a distinctive personality revealed through their movement, their attitudes, their postures, their gestures, their clothing and the special things they sold. Marcellus Laroon’s Cries possessed more life than any that had gone before, reflecting the dynamic renaissance of the City at the end of the seventeenth century.

Previous Cries had been published with figures arranged in a grid upon a single page, but Laroon gave each subject their own page, thereby elevating the status of the prints as worthy of seperate frames. And such was their success among the bibliophiles of London, that Laroon’s original set of forty designs – reproduced here – commissioned by the entrepreneurial bookseller Pierce Tempest in 1687 was quickly expanded to seventy-four and continued to be reprinted from the same plates until 1821. Living in Covent Garden from 1675, Laroon sketched his likenesses from life, drawing those he had come to know through his twelve years of residence there, and Pepys annotated eighteen of his copies of the prints with the names of those personalities of seventeenth century London street life that he recognised.

Laroon was a Dutchman employed as a costume painter in the London portrait studio of Sir Godfrey Kneller – “an exact Drafts-man, but he was chiefly famous for Drapery, wherein he exceeded most of his contemporaries,” according to Bainbrigge Buckeridge, England’s first art historian. Yet Laroon’s Cries of London, demonstrate a lively variety of pose and vigorous spontaneity of composition that is in sharp contrast to the highly formalised portraits upon which he was employed.

There is an appealing egalitarianism to Laroon’s work in which each individual is permitted their own space and dignity. With an unsentimental balance of stylisation and realism, all the figures are presented with grace and poise, even if they are wretched. Laroon’s designs were ink drawings produced under commission to the bookseller and consequently he achieved little personal reward or success from the exploitation of his creations, earning his living by painting the drapery for those more famous than he and then dying of consumption in Richmond at the age of forty-nine. But through widening the range of subjects of the Cries to include all social classes and well as preachers, beggars and performers, Marcellus Laroon left us us an exuberant and sympathetic vision of the range and multiplicity of human life that comprised the populace of London in his day.

Images photographed by Alex Pink & reproduced courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

Peruse these other sets of the Cries of London I have collected

More John Player’s Cries of London

More Samuel Pepys’ Cries of London

Geoffrey Fletcher’s Pavement Pounders

William Craig Marshall’s Itinerant Traders

H.W.Petherick’s London Characters

John Thomson’s Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana II

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana III

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders