Nick Garrett At The George

Nick Garrett signwriting upon The George

Behold the mighty George Tavern standing majestic in Stepney, as it has for centuries, presiding regally over the traffic along the main road to and from the City of London. From the medieval era, this ancient watering hole was known as the Halfway House and stood upon White Horse Lane that once ran along the back of the property but since 1802-6, when Commercial Rd was cut through on the other side of the building by the East India Company, it acquired the stucco frontage you see today and was renamed The George after George III, the monarch of the time.

For the past eleven years, the building has been undergoing renovation under the fond stewardship of Pauline Forster who has devoted herself to the care of this beloved East End landmark and, on Sunday, I went down to witness signwriter Nick Garrett apply the gold leaf upon the fascia as one of the finishing touches, completing the refurbishment of the exterior. The winter sunlight bathed The George in a warm glow as if to celebrate the restoration, illuminating the words ‘George Tavern’ in newly-applied gold leaf for the benefit of anyone travelling eastward down the Commercial Rd who might need a gentle reminder of this ideal spot for refreshment en route.

Yet when I arrived around three o’clock, the sunlight was already glimmering and the dark clouds gathering and Nick Garret had his work cut out to finish the job before daylight faded. “Every second counts in this job,” he reminded me, peering over his shoulder anxiously towards the setting sun, as I climbed upon the scaffolding to join him. With the confidence of a master, Nick was painting ‘Cask Ales’ freehand in size prior to applying the gold leaf and, in his absorption, he confided to me that it was a job which inevitably brought to mind his signwriting predecessor whose work he was replacing.

“For ten years, when I started as a signwriter, all I did was gilding pubs for Watneys and Taylor Walker. I remember the guy who did this lettering, the last time it was painted, about 1978. His lettering was eccentric, he was from the old school. We were being expected to paint commercial fonts then but he struggled with it, because his hands wanted to go another way, yet his lettering was really nice and his ‘S’s were distinctive – that’s what I recognise here.

My grandfather was my mentor, Francis Baker born in 1901. He was a lettercutter, the fourth generation of Francis Bakers of Fulham. They worked for Thorneycrofts, who made most of the statuary in central London, and they cut the lettering on the plinth of Boudicea on Westminster Bridge. He was a very old man when he used to come to my studio and he’d say, ‘Nick, that’s marvellous!’

I was so lucky with the Taylor Walker brewery because I just made a phone call one day and the chief surveyor answered. He said, ‘Come over and show me what you can do.’ So I went over there in my little minivan and came out with about ten years worth of work. In the eighties, we got hit by the wave of vinyl signs and I lost half my business, so I went into wood-graining and french-polishing just to make a living. But now designers are demanding signwriting and there’s a huge resurgence in the trade.

I live in Italy and come over for a couple of weeks at a time to get all the jobs done, and I teach youngsters who come to me to learn signwriting at workshops in Sydenham. It’s an interesting time now because there’s so many people wanting to learn the skills. There’s so much work – any job I can’t do, I pass to my students.”

By this point, Nick was pressing the squares of Italian gold leaf onto the newly-painted size that had just reached the necessary degree of tackiness, and the sun was setting in the sky and his freshly-gilded lettering was catching the first gleam of the street lights as they flickered on in Commercial St.

The stucco detail of ropework, egg and dart, and floral border has been recast from fragments

Nick Garrett paints freehand in size upon the fascia prior to application of the gold leaf

The George Tavern upon Commercial Rd in the early nineteenth century

You may like to read more about the history

Winter Light In Spitalfields

We are back in December again and the inexorable descent into the winter darkness has begun, even if just three weeks from now we shall reach the equinox and days will start to lengthen. At this season, I am more aware of light than at any other – especially when the city languishes under an unremitting blanket of low cloud, filtering the daylight into a grey haze that casts no shadow.

Yet on recent mornings I have woken to sunlight and it lifts my spirits to walk out through the streets under a clear sky. On such days, the low-angled sunshine and its attendant deep shadow conjures an exhilarating drama.

In these particular conditions of light, walking from Brick Lane down Fournier St is like advancing through a cave towards the light, refracting around the vast sombre block of Christ Church that guards the entrance. The street runs from east to west and, as the sun declines, its rays enter through the churchyard gates next to Rectory illuminating the houses opposite and simultaneously passing between the pillars at the front of the church to deliver light at the western end where it meets Commercial St.

For a spell, the shadows of the stone balls upon the pillars at the churchyard gate fall upon the houses on the other side of the street and then the rectangle of light, admitted between the church and the Rectory, narrows from the width of a house to single line before it fades out. At the junction with Commercial St, the low-angled sun directed through the pillars in the portico of Christ Church casts tall parallel bars of light and shade that travel down Fournier St from the Ten Bells as far as number seven, reflecting off the window panes to to create a fleeting pattern like stars within the gloom of the old church wall.

As you can see from these photographs, I captured these transient effects of light with my camera to share with you as a keepsake of winter sunshine, for consolation when those clouds descend again.

The last ray

The shadow of the cornice of Christ Church upon the Rectory

The shadow of the pillars of Christ Church upon Fournier St

Windows in Fournier St reflecting upon the church wall

In Princelet St

You may also like to read about

Towers Over The Goodsyard

Spitalfields Life Contributing Photographer Simon Mooney presents his completed film

[youtube wBbckajC91Q nolink]

Click here to read the East End Preservation Society’s guide to how to object effectively

You may also like to read about

Kitty Jennings, New Era Estate

No doubt you have read in the national press of the plight of the New Era Estate in Hoxton which has recently been acquired by an American property company that seeks to increase the rents to market value, disregarding the circumstances of the residents many of whom live upon modest incomes.

Today I publish my interview with long-term occupant, Kitty Jennings – drawing my readers attention to the petition, which already has over a quarter of a million signatories, and the public demonstration which gathers outside the offices of Westbrook Partners in Berkeley Sq at 12:30pm on Monday and marches to Downing St to present the petition, demanding justice for the tenants of the New Era Estate. Kitty is not as mobile as she once was, but she hopes some Spitalfields Life readers might be able to attend on her behalf.

Kitty, Amelia (Doll Doll), Jimmy, Gracie & Patricia Jennings, Gifford St, Hoxton c.1930

One Sunday afternoon last summer, I walked over to Columbia Rd Market to get a bunch of flowers for Kathleen – widely known as Kitty – Jennings, who has lived in Hoxton since 1924. I found her in her immaculately tidy flat in the New Era Estate near the canal where for many years she lived with her beloved sister Doll Doll, whose ashes now occupy pride of place in a corner of the sitting room.

Once Barbara Jezewska, who grew up in Spitalfields and was Kitty’s neighbour in this building for seventeen years, had made the introductions, we settled down in the afternoon sun to enjoy beigels with salmon and cream cheese while Kitty regaled us with her memories of old Hoxton.

“Thank God we were lucky, we had a father who had a good job, so we always had a good table. There was not a lot of work when I was a kid, but we always got by. We were lucky that we always had good clothes and never got knocked about.

My father, Jim, he was a Fish Porter at Billingsgate Market and he had to work seven days. He was born in the Vinegar Grounds in Hoxton, where they only had one shared tap in the garden for all the cottages, and he was a friendly man who would help anyone. He left for work at four in the morning each day and came back in the early afternoon. We lived on fish. I’m a fish-mullah, I like plaice, jellied eels, Dover sole and middle skate. My poor old mum used to fry fish night and day, she was always at the gas stove.

I was born in Gifford St, Hoxton. There were five of us, four girls and one boy, and we lived in a little three bedroom house. My mother Grace, her life was cooking, washing and housework. She didn’t know anything else.

When my sister Amelia was born, she was so small they laid her in a drawer and we called her ‘Doll Doll.’ They put her in the Queen Elizabeth Children’s Hospital when she had rheumatic fever and she didn’t go to school because of that. She was happy-go-lucky, she was my Doll Doll.

One day, when she was at school, there was an air raid and all the children hid under the tables. They saw a man’s legs walk in and Doll Doll cried out, ‘That’s my dad!’ and her friend asked, ‘How do you recognise him?’ and Doll Doll said, ‘Because he has such shiny shoes.’ He took Doll Doll and said to the teacher, ‘My daughter’s not coming to school any more.’

I was dressmaking from when I left school at fourteen. My first job was at C&A in Shepherdess Walk but I didn’t like it, so I told my mum and left. I left school at Easter and the war came in August. After that, I didn’t go to work at all for five years. Then I went to work in Bishopsgate sewing soldiers’ trousers, I didn’t like that much either so I stayed at home.

Doll Doll and I, we used to love going to Hoxton Hall for concerts every Saturday. It cost threepence a ticket and there was a man called Harry Walker who’d sling you out if you didn’t behave. Afterwards, we’d go to a stall outside run by my uncle and he’d give us sixpence, and we’d go and buy pie and mash and go home afterwards – and that was our Saturday night. We used to go there in the week too and do gym and see plays.

On Friday nights, we’d go to the mission at Coster’s Hall and they’d give you a jug of cocoa and a biscuit, and the next week you’d get a jug of soup. It didn’t cost anything. We used to go there when we were hungry. In the school holidays, we went down to Tower Hill Beach and we’d cut through the market and see my dad, and he’d give us a few bob to buy ice cream.

Me and Doll Doll, we stayed at home with my mum and dad. The other three got married but I didn’t want to. I couldn’t find anybody that I liked, so I stayed at home with mummy and daddy, and I was quite happy with them. When they got old we cared for them at home, without any extra help, until they died. We had understanding guvnors and, Doll Doll and I took alternate weeks off work to care for them.

Doll Doll and I moved into the New Era Estate more than thirty years ago. In those days, it was only women and once, when my neighbour thought her boiler was going to explode, we called the fire brigade. Doll Doll leaned over the balcony and called, ‘Coo-ee, young man! Up here!’

We never went outside Hoxton much when we were young, but – when we grew up – Doll Doll and I went to Florida and Las Vegas. I finally settled down and I didn’t wander no more. I worked as a dressmaker at Blaines in Petticoat Lane for thirty-five years, until it closed forty years ago and I was made redundant.”

Doll Doll, Kitty and their mother Grace

Kitty in her flat in Hoxton

Kitty places fresh flowers next to Doll Doll’s ashes each week

Kitty at a holiday chalet in Guernsey, 1960

Kitty Jennings with her friend and neighbour of sixteen years, Barbara Jezewska

You may also like to read about

Remembering AS Jasper’s ‘A Hoxton Childhood’

Happy Birthday East End Preservation Society!

It was a year ago this week that several hundred people gathered in the Great Hall at the Bishopsgate Institute to found The East End Preservation Society, as a means to unite everyone who cares about the future of the East End and its built environment. The creation of the Society was inspired by the saving of the Marquis of Lansdowne from demolition and in response to the looming prospect of a slew of large-scale development proposals threatening to blight the East End for generations to come.

Early on, the Society won a victory in Whitechapel when a characterful nineteenth century terrace, which had been condemned, was revealed to be the last fragment of the Pavilion Theatre complex and was subsequently rescued from destruction. Yet the last year has also witnessed the tragic demolition of the Queen Elizabeth Children’s Hospital soon to be followed by the Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange. Meanwhile, in the last few days, a brave initiative by Open Dalston failed to prevent Hackney Council proceeding to demolish the Georgian terrace in Dalston Lane as part of a “Conservation-led” scheme.

To address these challenges at the first opportunity, a team of Conservation specialists have come together who now meet monthly to consider all relevant planning applications and devise the most effective letters of response on behalf of The East End Preservation Society. In parallel to this, there is a popular programme of public talks upon pertinent subjects – such as Community Planning and The History of the Bishopsgate Goodsyard – and tickets for all these events always sell out in advance. A lively facebook page highlights campaigns arising in the East End and permits anyone to bring new cases to the attention of the Society.

At this moment the Society faces the largest battle it is ever likely to face, in the form of the monstrous proposals for the Bishopsgate Goodsyard, described recently as “the biggest thing to hit Shoreditch since the plague” and “degeneration not regeneration” by two eloquent critics. The Society has created a clear guide that explains how to object, outlining the salient points which carry weight with planning committees.

Next year, the Society hopes to raise the level of debate upon the current planning crisis in London with the Inaugural CR Ashbee Memorial Lecture in the Great Hall at the Bishopsgate Institute. We choose to remember CR Ashbee (1863-1942) as founder of the Guild of Handicrafts in the East End, as a pioneer of the Conservation Movement, and a Progressive Architect and Designer whose influence was seminal upon Frank Lloyd Wright among many others. The intention of this endeavour is to invite high-profile speakers to address the most pressing questions for the future of London and its built environment, stimulating a debate that can redress the contemporary situation.

I am proud to announce that Oliver Wainwright, Architecture & Design Critic of The Guardian, has accepted the invitation to deliver The East End Preservation Society’s Inaugural CR Ashbee Memorial Lecture in April 2015, which will be entitled “The Seven Dark Arts of Developers.”

But before we get to that, British Land who demolished the best part of the Georgian houses in Elder St in the nineteen-seventies before they were halted by the opposition of Dan Cruickshank, John Betjeman and others, have returned with a new scheme to redevelop Norton Folgate. In the next few days, they are staging a public exhibition of their final proposals prior to submitting the planning application in December. Readers are encouraged to visit and record their responses in writing at this event.

The Marquis of Lansdowne to be restored by the Geffrye Museum as part of its development plans

Whitechapel’s Theatrical terrace saved from demolition (Photo by Alex Pink)

The Queen Elizabeth Children’s Hospital has been demolished this year

The Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange will be demolished next year

The Georgian terrace in Dalston Lane will be demolished next year (Photo by Simon Mooney)

The proposed development for the Bishopsgate Goodyard

‘A new Society is needed to promote an urban vision which is not governed by short term and personal profit, but which evokes and embraces the communal aims which enshrine the spirit and character of east London.’ – Dan Cruickshank, at the launch of The East End Preservation Society, November 2013

British Land’s invitation to the exhibition of their final plans for Norton Folgate

Follow the East End Preservation Society

Facebook/eastendpsociety

Twitter/eastendpsociety

Click here to join the East End Preservation Society

You may also like to read about

The East End Preservation Society

The Launch of The East End Preservation Society

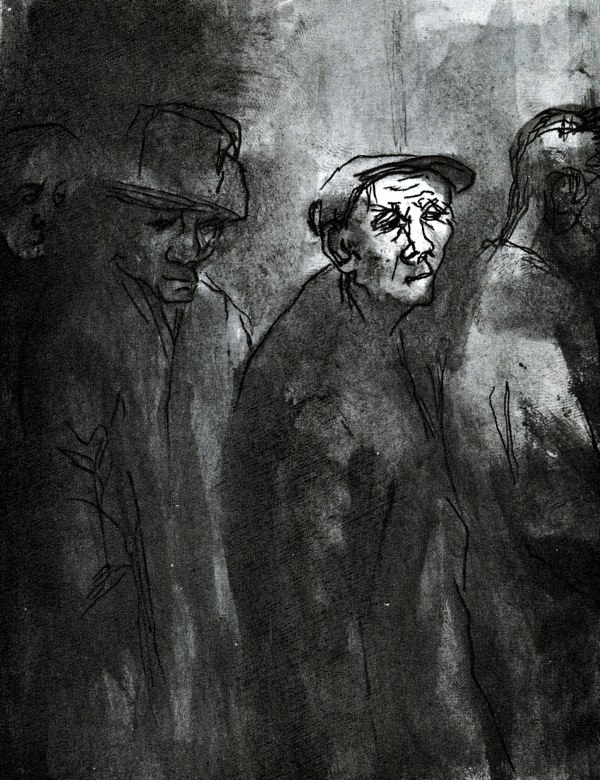

Eva Frankfurther, Artist

There is an unmistakeable melancholic beauty which characterises Eva Frankfurther‘s East End drawings made during her brief working career in the nineteen-fifties. Born into a cultured Jewish family in Berlin in 1930, she escaped to London with her parents in 1939 and studied at St Martin’s School of Art between 1946 and 1952, where she was a contemporary of Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach.

Yet Eva turned her back on the art school scene and moved to Whitechapel, taking menial jobs at Lyons Corner House and then at a sugar refinery, immersing herself in the community she found there. Taking inspiration from Rembrandt, Käthe Kollwitz and Picasso, Eva set out to portray the lives of working people with compassion and dignity.

In 1958, afflicted with depression, Eva took her own life aged just twenty-eight, but despite the brevity of her career she revealed a significant talent and a perceptive eye for the soulful quality of her fellow East Enders.

“West Indian, Irish, Cypriot and Pakistani immigrants, English whom the Welfare State had passed by, these were the people amongst whom I lived and made some of my best friends. My colleagues and teachers were painters concerned with form and colour, while to me these were only means to an end, the understanding of and commenting on people.” – Eva Frankfurther

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also wish to take a look at