Ben Hur’s Stepney

The Palaseum Cinema (also known as the Ben Hur) painted by Doreen Fletcher, 1985

Ian Ben Hur, grandson of Ben Hur who was both projectionist and proprietor at the Palaseum Cinema in White Horse Rd, Stepney from 1917, sent me this glorious film celebrating a party thrown by his grandfather for eight hundred children at the Jubilee of 1935. Ben placed a camera on the front of a car to take some of the shots and showed the completed film to audiences at his cinema. How much I would love to have been there to witness their reaction.

Too often, we think of the East End in the thirties as defined by social problems, the poverty and deprivation, and the rise of fascism, yet these images confront us with the vitality of that society. The delightful sequences of crowds arriving at the cinema remind me of the Lumiere Brothers’ film of workers leaving the factory, with spectators offering spontaneous greeting as they recognise the camera. Above all, the wonder of this film is the exuberance of the community which is conveyed and no viewer can fail to be touched by these joyful personalities presenting themselves to the lens with such confident self-possession.

Ben Hur was born Henry Ben Solomon, but changed his name by deed poll to Ben Hur after gaining fame by beating a market bully who was a bare-knuckle boxing champion after seventy-seven rounds. He made money with a stage act as The World Strongest Man and used it to buy businesses including the Palaseum. Renowned for his charitable endeavours including donations to the Royal London Hospital, Ben lived until in 1960.

The Ben Hur cinema which was also known as the Palaseum was converted to a bingo club in 1962 and then a snooker club in the eighties, closing in 2007 before the building was demolished in 2008.

[youtube hzZ5rPWAC_c nolink]

Celebrations in Challis Court by Rose Henriques (Courtesy of Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives)

The Pubs Of Old London

The Vine Tavern, Mile End

I cannot deny I enjoy a drink, especially if there is an old pub with its door wide open to the street inviting custom, like this one in Mile End. In such circumstances, it would be affront to civility if one were not to walk in and order a round. Naturally, my undying loyalty is to The Golden Heart in Commercial St, as the hub of our existence here in Spitalfields and the centre of the known universe. But I have been known to wander over to The Carpenters’ Arms in Cheshire St, The George Tavern in Commercial Rd and The Marksman in Hackney Rd when the fancy takes me.

So you can imagine my excitement to discover all these thirst-inspiring images of the pubs of old London among the thousands of glass slides – many dating from a century ago – left over from the days of the magic lantern shows given by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society at the Bishopsgate Institute. It did set me puzzling over the precise nature of these magic lantern lectures. How is it that among the worthy images of historic landmarks, of celebrated ruins, of interesting holes in the ground, of significant trenches and important church monuments in the City of London, there are so many pictures of public houses? I can only wonder how it came about that the members of the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society photographed such a lot of pubs, and why they should choose to include these images in their edifying public discourse.

Speaking for myself, I could not resist lingering over these loving portraits of the pubs of old London and I found myself intoxicated without even lifting a glass. Join me in the cosy barroom of The Vine Tavern that once stood in the middle of the Mile End Rd. You will recognise me because I shall be the one sitting in front of the empty bottle. Bring your children, bring your dog and enjoy a smoke with your drink, all are permitted in the pubs of old London – but no-one gets to go home until we have visited every one.

The Saracen’s Head, Aldgate

The Grapes, Limehouse

George & Vulture, City of London

The Green Dragon, Highgate

The Grenadier, Old Barrack Yard

The London Apprentice, Isleworth

Mitre Tavern, Hatton Garden

The Old Tabard, Borough High St

The Three Compasses, Hornsey

The White Hart, Lewisham

The famous buns hanging over the bar at The Widow’s Son, Bow

The World’s End, Chelsea, with the Salvation Army next door.

The Angel Inn, Highgate

The Archway Tavern, Highgate

The Bull, Highgate

The Castle, Battersea

The Old Cheshire Cheese, Fleet St

The Old Dick Whittington, Cloth Fair, Smithfield

Fox & Crowns, Highgate

The Fox, Shooter’s Hill

The Albion, Barnesbury

The Anchor, Bankside

The George, Borough High St

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

Sandra Esqulant, The Golden Heart

The Carpenter’s Arms, Gangster Pub

Philip Mernick’s Mortlake Jugs

Once, every household in London possessed an ale jug, in the days before it was safe to drink water or tea became widely affordable. These cheaply-produced salt-glazed stoneware items, that could be bought for a shilling or less, were prized for their sprigged decoration and often painstakingly repaired to extend their lives, and even prized for their visual appeal when broken and no longer of use.

All these jugs from the collection of Philip Mernick were produced in Mortlake, when potteries were being set up around London to supply the growing market for these household wares throughout the eighteenth century. The first of the Mortlake potteries was begun by John Sanders and taken over by his son William Sanders in 1745, while the second was opened by Benjamin Kishere who had worked for Sanders, and this was taken over by his son William Kishere in 1834.

These jugs appeal to me with their rich brown colouration that evokes the tones of crusty bread and their lively intricate decoration, mixing images of English country life with Classical motifs reminiscent of Wedgwood. Eighteenth-century Mortlake jugs are distinguished by the attenuated baluster shape that follows the form of ceramics in the medieval world yet is replaced in the early-nineteenth century by the more bulbous form of a jug which is still common today.

There is an attractive organic quality to these highly-wrought yet utilitarian artefacts, encrusted with decorative sprigs like barnacles upon a ship’s hull. They were once universally-familiar objects in homes and ale houses, and in daily use by Londoners of all classes.

1790s ale jug repaired with brass handle and engraved steel rim

A panel of “The Midnight Conversation” after a print by Hogarth

Classical motifs mixed with rural images

A panel of “Cupid’s Procession”

A woman on horseback portrayed on this jug

Agricultural implements and women riders

Toby Fillpot

Panel of Racehorses

Cupid’s procession with George III & Queen Charlotte and Prince of Wales & Caroline of Brunswick

Panel of “Cockerell on the Dungheap”

Panel of “The Two Boors”

Square- based jug of 1800/1810

Toby Fillpot

William Kishere, Pottery Mortlake, Surrey

You may also like to look at

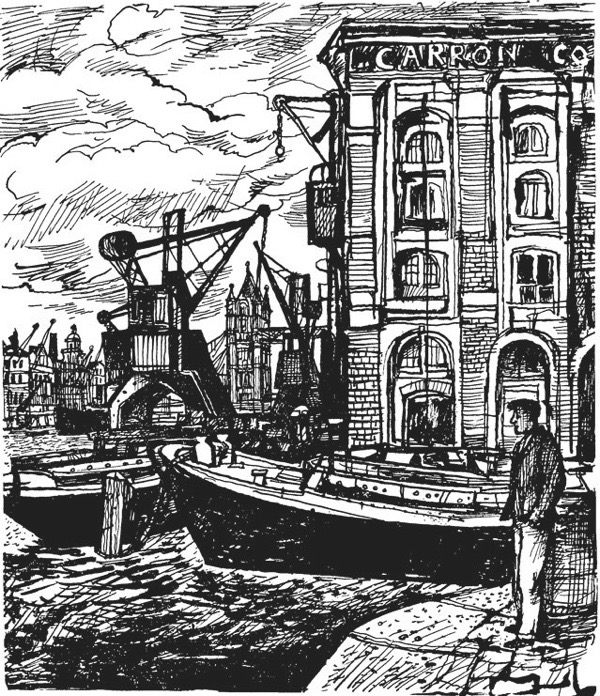

John Minton’s East End

Martin Salisbury author of The Snail that climbed the Eiffel Tower, a monograph of John Minton’s graphic work, explores Minton’s fascination with the East End.

Never quite accepted by the establishment during his brief, rather tragic life, artist John Minton (1917—1957) has divided opinion ever since. Brilliant illustrator, inspirational teacher, prodigious habitué of Soho and Fitzrovia drinking establishments, Minton was bound to enter the folklore of post-war London. Somehow, he embodied the mood of elegiac romanticism that pervaded the arts through the forties and into the early fifties before fizzling out to be replaced by a more forward-looking, assertive art in the form of American abstract expressionism and British ‘kitchen-sink’ realism.

His life, riddled as it was with contradictions, began on Christmas Day 1917 in a wooden house near Cambridge, of an architectural style that some have termed ‘Gingerbread,’ and ended just under forty years later in Chelsea. He had apparently taken his own life.

This year’s centenary of Minton’s birth bring recognition to an artist who has not previously enjoyed the attention that has come the way of those other mid-century greats, Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious and John Piper. An exhibition at Pallant House, Chichester this summer gathered many of his paintings that have received mixed responses over the years. Rooms were devoted to his portraits, his various epic narrative paintings and his neo-romantic landscapes. Alongside his ‘longing to be away’ paintings of Corsica, Jamaica and Spain, there were also many depictions of London. In particular, it was London’s dockland that he returned to repeatedly.

Arguably, John Minton was at his best as a graphic and commercial artist, perhaps best known for his sublime illustrations for publisher John Lehmann to Elizabeth David’s highly influential food writing and Alan Ross; Corsica travel journal, Time Was Away, a lavish anti-austerity production. Yet Minton’s urban romanticism found its way into many commercial commissions too. Wartime drawings of bombed-out buildings in Poplar still exhibited the samr overwrought theatricality that was a feature of his work while under the spell of friend and fellow artist, Michael Ayrton.

In the immediate post-war years, as Minton’s work drew more consistently on direct observation, his visual vocabulary matured and his frequent visits to the river resulted in a mass of drawings of the cranes and wharves of the Port of London and Bankside. Rotherhithe from Wapping was painted in 1946 and a three-colour lithograph of the same composition followed two years later, renamed Thames-side.

The flattened perspective in this pictures embraces barges in the foreground and the jumble of warehouses on the far bank in the background. Typically, this image includes a pair of male figures in intimate conversation. Minton’s sexuality was central to his work and these dockland images embody the frustration he felt as a gay man at a time when sex between men was illegal. The many hours that Minton spent haunting the riverside allowed him not only to draw but to enjoy the company of sailors and dockers. Time and again, his pictures feature solitary male figures or distant pairs, huddled together, walking at low tide or working on boats, dwarfed by the surrounding buildings and brooding clouds.

John Minton’s only commission for London Transport came from publicity officer, Harold F. Hutchison in the form of a ‘pair poster’ titled London’s River. This concept involved posters designed in adjoining pairs, with one side featuring a striking pictorial image and the other containing text. The familiar dockland images are reworked here in gouache, in similar manner to the series of paintings commissioned for Lilliput in July 1947, London River.

An unpublished rough cover design for The Leader magazine executed in 1948 features another of Minton’s favourite motifs, the elevated street view. In this instance, the foreground figure gazing from an upper window bears more than a passing resemblance to the artist himself. The composition takes us beyond the streets below to the Thames via the dome of St Paul’s. A similar view, this time of the author’s native Hackney, graces the dust jacket of Roland Camberton’s Rain on the Pavements, published in 1951 by John Lehmann. This was the second of Camberton’s two novels, both with dust jackets designed by Minton, and tells the story of David Hirsch’s early years growing up in Hackney Jewish society.

In his 2008 article Man in a MacIntosh, Iain Sinclair followed in the footsteps of a fellow Hackney writer, recognising, “Camberton, in choosing to set ‘Rain on the Pavements’ in Hackney, was composing his own obituary. Blackshirt demagogues, the spectre of Oswald Mosley’s legions, stalk Ridley Rd Market while the exiled author ransacks his memory for an affectionate and exasperated account of an orthodox community in its prewar lull.”

John Minton’s magnificent jacket design draws us into that world with effortless elegance.

Rain on the Pavements, 1951

Scamp, 1950

Wapping, 1941

Bomb-damaged buildings, Poplar, 1941

Rotherhithe from Wapping, 1946

London Bridge from Cannon Street Station, 1946

London’s River, Lilliput 1947

London’s River, Lilliput 1947

London’s River, Lilliput 1947

Illustrations from Flower of Cities, 1949

London’s River: Pool of London, London Transport, 1951

The Leader, 1948

Isle of Dogs from Greenwich, 1955

Illustrations copyright © Estate of John Minton

You may also like to read about Alfred Daniels & Terry Scales who were taught by John Minton

Maurice Evans, Self-Taught Pyrotechnician

On Bonfire Night, my thoughts turn to Maurice Evans, Britain’s Pyrotechnician Extraordinaire

Maurice Evans

Maurice Evans has been collecting fireworks since childhood and now over eighty years old, he has the most comprehensive collection in the country – so you can imagine both my excitement and my trepidation upon stepping through the threshold of his house in Shoreham. My concern about potential explosion was relieved when Maurice confirmed that he has removed the gunpowder from his fireworks, only to be reawakened when his wife Kit helpfully revealed that Catherine Wheels and Bangers were excepted because you cannot extract the gunpowder without ruining them.

This statement prompted Maurice to remember with visible pleasure that he still had a collection of Second World War shells in the cellar and, of course, the reinforced steel shed in the garden full of live fireworks. “Let’s just say, if there’s a big bang in the neighbourhood, the police always come here first to see if it’s me,” admitted Maurice with a playful smirk. “Which it often isn’t,” added Kit, backing Maurice up with a complicit demonstration of knowing innocence.

“It all started with my father who was in munitions in the First World War,” explained Maurice proudly, “He had a big trunk with little drawers, and in those drawers I found diagrams explaining how to work with explosives and it intrigued me. Then came World War II and the South Downs were used as a training ground and, as boys, we went where we shouldn’t and there were loads of shells lying around, so we used to let them off.”

Maurice’s radiant smile revealed to me the unassailable joy of his teenage years, running around the downs at Shoreham playing with bombs. “We used to set off detonators outside each other’s houses to announce we’d arrived!” he bragged, waving his left hand to reveal the missing index finger, blown off when the explosive in a slow fuse unexpectedly fired upon lighting. “That’s the worst thing that happened,” Maurice declared with a grimace of alacrity, “We were worldly wise with explosives!”

Even before his teens, the love of pyrotechnics had taken grip upon Maurice’s psyche. It was a passion born of denial. “I used to suffer from bronchitis and asthma as a child, so when November 5th came round, I had to stay indoors.” he confided with a frown, “Every shop had a club and you put your pennies and ha’pennies in to save for fireworks and that’s what I did, but then my father let them off and I had to watch through the window.”

After the war, Maurice teamed up with a pyrotechnician from London and they travelled the country giving displays which Maurice devised, achieving delights that transcended his childhood hunger for explosions. “In my mind, I could envisage the sequence of fireworks and colours, and that was what I used to enjoy. You’ve got all the colours to start with, smoke, smoke colours, ground explosions, aerial explosions – it’s endless the amount of different things you can do. The art of it is knowing how to choose.” explained Maurice, his face illuminated by the images flickering in his mind. Adding, “I used to be quite big in fireworks at one time.” with calculated understatement.

Yet all this personal history was the mere pre-amble before Maurice led me through his house, immaculately clean, lined with patterned carpets and papers and witty curios of every description. Then in the kitchen, overlooking the garden lined with old trees, he opened an unexpected cupboard door to reveal a narrow red staircase going down. We descended to enter the burrow where Maurice has his rifle range, his collections, model aeroplanes, bombs and fireworks – all sharing the properties of flight and explosiveness. Once they were within reach, Maurice could not restrain his delight in picking up the shells and mortars of his childhood, explaining their explosive qualities and functions.

But my eyes were drawn by all the fireworks that lined the walls and glass cases, and the deep blues, lemon yellows and scarlets of their wrappers and casings. Such evocative colours and intricate designs which in their distinctive style of type and motif, draw upon the excitement and anticipation of magic we all share as children, feelings that compose into a lifelong love of fireworks. Rockets, Roman Candles, Catherine Wheels, Bangers, and Sparklers – amounting to thousands in boxes and crates, Maurice’s extraordinary collection is the history of fireworks in this country.

“I wouldn’t say its made my life, but its certainly livened it up,” confided Maurice, seeing my wonder at his overwhelming display. Because no-one (except Maurice) keeps fireworks, there is something extraordinary in seeing so many old ones and it sets your imagination racing to envisage the potential spectacle that these small cardboard parcels propose.

Maurice outgrew the bronchitis and asthma to have a beautiful life filled with fireworks, to visit firework factories around Britain, in China, Australia, New Zealand and all over Europe, and to scour Britain for collections of old fireworks, accumulating his priceless collection. Now like an old dragon in a cave, surrounded by gold, Maurice guards his cellar hoard protectively and is concerned about the future. “It needs to be seen,” he said, contemplating it all and speaking his thoughts out loud, “I would like to put this whole collection into a museum. I don’t want any money. I want everyone to see what happened from pre-war times up until the present day in the progression of fireworks.”

“My father used to bring me the used ones to keep,” confessed Maurice quietly with an affectionate gleam in his eye, as he revealed the emotional origin of his collection, now that we were alone together in the cellar. With touching selflessness, having derived so much joy from collecting his fireworks, Maurice wants to share them with everybody else.

Maurice with his exploding fruit.

Maurice with his barrel of gunpowder

Maurice with his grenades.

Maurice with two favourite rockets.

Firework photographs copyright © Simon Costin

Read my story about Simon Costin, The Museum of British Folklore

So Long, Glenys Bristow

Linda Hayes wrote with the sad news that her mother Glenys Bristow died aged ninety-five last Sunday. Today we celebrate the life of a woman of astonishing resilience who lived and worked in Spitalfields during the Second World War.

Glenys with her dad Stanley Arnabaldi in their cafe at 100 Commercial St

When I met Glenys Bristow, she did not live in Spitalfields anymore but in a well-kept flat in a quiet corner of Bethnal Green. Glenys might never even have come to Spitalfields if the Germans had not dropped a bomb on her father’s cafe in Mansell St, down below Aldgate. In fact, Glenys would have preferred to stay in Westcliff-on-Sea and never come to London at all, if she had been given the choice. Yet circumstances prevailed to bring Glenys to Spitalfields. And, as you can see from this picture taken in 1943 – in the cafe she ran with her father opposite the market – Glenys embraced her life in Spitalfields wholeheartedly.

“I came to London from Westcliff-on-Sea when I was fifteen. I didn’t like London at all. At first we were in Limehouse, I walked over to Salmon Lane and there was Oswald Mosley making a speech to his blackshirts. The police told us to go home. I was sixteen and I missed Westcliff so, me and my friend, we took a job in a cafe there for the Summer. We were naive. We weren’t streetwise. We didn’t have confidence like kids do today.

The family moved to Mansell St where had a cafe – our first cafe – and we lived above it. My father’s name was Arnabaldi, I used to hate it when I was at school. My father always wanted to have a cafe of his own. His father had come over from Italy and ran a shop in Friern Barnet but died when my father was only eleven, and my father told me his mother died young of a broken heart.

In September 1940, we were bombed out of Mansell St. Luckily no-one was inside at the time because it was the weekend. It was a big shock. My mother, sister Rita and brother Raymond had gone to Wales to visit my grandparents in the Rhonda Valley. I’d left that afternoon with my husband Jack, who was my boyfriend then. We had something to eat at his sister’s then we went by bus to my future in laws at Old St, where we slept in an Anderson shelter. On Monday morning, we were walking back to Mansell St and these people asked, “Where are you going?” I said, “Home, I’m going to change before going to work.” “You’ll be lucky,” they said. When we got there we found the site roped off. It was all gone. Just a pile of rubble.”

Glenys got married at eighteen years old at Arbour Sq Registry Office when Jack was enlisted.”We didn’t know if we were going to be here from one day to the next,”she told me, describing her experience of living through the blitz, suffering the destruction of her home in the bombing and then finding herself alone with a baby while her husband was at war.

“In late 1942, my father got the cafe at 100 Commercial St, Spitalfields, and I was living in a little house in Vallance Rd and had my first baby John and he was just eleven months old. My father bought the cafe and he arranged for me to stay in the top floor flat next door at 102, Commercial St. We just had two rooms above some offices with a cooker on the landing and a toilet. When the air raid sirens went, I didn’t want to get out of bed so my dad fixed up a bell on a string from next door. I used to wrap my baby in an eiderdown and wait until the shrapnel had stopped flying before I went out of the door into the street to the cafe next door.

I did a bit of everything, cooking, serving behind the counter. People came in from the Godfrey & Phillips cigarette factory, the market and all the workshops. The fruit & vegetable market kept going all through the war but, because of the blackout, it started later in the night. We were lucky being close to the market, we were never short of anything.

At the end of the war, Jack came back and worked for my parents until, after a few years, the lease on the cafe ran out and we had to give it up. In 1956, we rented a little cafe in Hanbury St that belonged to the Truman Brewery, but we were only there three years before we had to move again because they had expansion plans. We bought the cafe opposite where Bud Flanagan had been born and called it Jack’s Cafe. And we were there from 1960 until 1971.

Because of the market, we had to have dinner ready to serve at nine in the morning, and again from twelve ’til two. Nothing was frozen, everything was cooked daily and Jack used to buy everything fresh from the market. They said we had the best and the cleanest cafe in the Spitalfields Market, and a lot of our customers became friends. My daughter met her husband there, he was a porter – his whole family were porters – and my son went to work as a porter, he was called an empty boy until he got his badge.

I just took it for granted. We used to open at half past four in the morning and I used to try and get cleaned up by half past six at night. It was very hard. Eventually, we sold it because I had back trouble and my husband bought a couple of lorries. In 1976, we moved from Commercial St to Chicksand St. I had four children altogether, only three that lived.

When it all changed, we went back – my daughter and I – to visit our old cafe. It had the same formica on the wall my husband had put up and I kept trying to look in the kitchen. I loved it when we worked for my mum and dad, and when we had our own place. I loved it and I miss it. They said I was the best pastry cook in Spitalfields.”

Glenys Bristow was a woman of astonishing resilience, possessing quick wits and a bright intelligence. Random events delivered her to Spitalfields in wartime, where she found herself at the centre of a lively working community. Losing everything when the bomb fell on her father’s cafe, and living day-to-day in peril of her life, she summoned extraordinary strength of character, bringing up her family and working long hours too. Glenys had no idea that she would live into another century, and enjoy the advantage of living peacefully in Bethnal Green and be able to look back on it all with affection.

Glenys Bristow (1922-2017)

Glenys’ home in Mansell St after the bomb dropped in 1940.

At the cafe in Mansell St.

Glenys and her daughter Linda, 1950

Glenys and Linda visit the site of the former cafe in Mansell St, 1951.

Glenys with her children, John, Linda and Alan.

Glenys and her husband Jack with their first car.

Stan, Jack, Glenys and her mother Anne on a day trip to Broxbourne.

Glenys’ identity card with Commercial Rd mistakenly substituted for Commercial St.

Glenys with her granddaughter Sue Bristow.

You may also like to read about

How To Eat A Pomegranate

Now is the season for pomegranates. All over the East End, I have spotted them gleaming in enticing piles upon barrows and Leila’s Shop in Calvert Avenue has a particularly magnificent display. Only a few years ago, these fruit were unfamiliar in this country and I do remember the first time I bought a pomegranate and set it on a shelf, just to admire it.

My father used to tell me that you could eat a pomegranate with a pin, which was an entirely mysterious notion. Yet it was not of any consequence, because I did not intend to eat my pomegranate but simply enjoy its intriguing architectural form, reminiscent of a mosque or the onion dome of an orthodox church and topped with a crown as a flourish. This was an exotic fruit that evoked another world, ancient and far away.

As months passed, my pomegranate upon the shelf would dry out and wither, becoming hard and leathery as it shrank and shrivelled like the carcass of a dead creature. A couple of times, I even ventured eating one when my rations were getting low and I was hungry for novelty. It was always a disappointing experience, tearing at the skin haphazardly and struggling to separate the fruit from the pithy fibre. Eventually, I stopped buying pomegranates, content to admire them from afar and satiate my appetite for autumn fruit by munching my way through crates of apples.

Then, last year, Leila McAlister showed me the traditional method to cut and eat a pomegranate – and thus a shameful gap in my education was filled, bringing these alluring fruit to fore of my consciousness again. It is a simple yet ingenious technique of three steps. First, you cut a circle through the skin around the top of the fruit and lever it off. This reveals the lines that naturally divide the inner fruit into segments, like those of an orange. Secondly, you make between four and eight vertical cuts following these lines. Thirdly, you prise the fruit open, like some magic box or ornate medieval casket, to reveal the glistening trove of rubies inside, attached to segments radiating like the rays of a star.

Once this simple exercise is achieved, it is easy to remove the yellow pith and eat the tangy fruit that is appealingly sharp and sweet at the same time, with a compelling strong aftertaste. All these years, I admired the architecture of pomegranates without fully appreciating the beauty of the structure that is within. Looking at the pomegranate displayed thus, I can imagine how you might choose to eat it one jewel at a time with a pin. It made me wonder where my father should have acquired this curious idea about a fruit which was rare in this country in his time and then I recalled that he had spent World War II in the Middle East as a youthful recruit, sent there from Devon at the age of nineteen.

Looking at the fruit opened, I realised I was seeing something he had seen on his travels so many years ago and now, more than ten years after he died, I was seeing it for the first time. How magical this fruit must have seemed to him when he was so young and far away from home for the first time. They call the pomegranate ‘the fruit of the dead’ and, in Greek mythology, Persephone was condemned to the underworld because of the pomegranate seeds that she ate yet, paradoxically, it was the fabled pomegranate which brought my youthful father back to me when he had almost slipped from my mind.

Now, thanks to this elegant method, I can enjoy pomegranates each year at this time and think of him.

“its intriguing architectural form, reminiscent of a mosque or the onion dome of an orthodox church and topped with a crown as a flourish”

First slice off the top, by running a sharp knife around the fruit, cutting through the skin and then levering off the lid.

Secondly, make radiating vertical cuts through the skin following the divisions visible within the fruit – between four and eight cuts.

Thirdly, split open the pomegranate to create a shape like a flower and peel away the pith.

[youtube JLUCSi4jRew nolink]

Leila’s Shop, 15-17 Calvert Avenue, London E2 7JP

You may also like to read my other stories about Leila’s Shop

Vegetable Bags from Leila’s Shop

Barn the Spoon at Leila’s Shop