The Doors Of Old London

The door to Parliament

Look at all the doors where the dead people walked in and out. These are the doors of old London. Some are inviting you in and some are shutting you out. Doors that lead to power and doors that lead to prison. Doors that lead to the parlour, doors that lead to the palace, and doors that lead to prayer. These are the doors that I found among hundreds of glass slides once used for magic lantern shows by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society, many more than a century old, and housed today at the Bishopsgate Institute.

Looking at life through a doorway, we are all either on the way in or on the way out. Like the door to your childhood home that got sold long ago, each one pictured here is evidence of the transient nature of existence, reminding you that you cannot go back through the portal of time.

Yet there is a powerful enigma conjured by these murky pictures of old doors, most of which will never open again. Like the pauper or the lost soul condemned to wander the streets, we cannot enter to learn what lies behind these doors of old London. But a closed door is an invitation to the imagination and we can wonder and dream, entering those hidden spaces in our fancy.

London has always been a city of doors, inviting both the curiosity and the suspicion of the passerby. In each street, there is a constant anticipation of people popping out, regurgitated onto the street by the building, and the glimpse to be snatched of the interior before the door closes again.

I cannot resist the notion that every door contains a mystery and all I need is a skeleton key. Then we can set out to explore as we please, going in one door and out another, until we have passed through all the doors of old London.

The entrance to the Carpenters’ Hall

The doors of Lambeth Palace

Door in the cloisters in Westminster Abbey

The door to the chamber of Little Ease at the Tower of London.

In St Benet’s Church, Paul’s Wharf.

Back door of 33 Mark Lane

Back door to Lancaster House.

In Crutched Friars.

14 Cavendish Sq.

The door to 10 Downing St

39a Devonshire St.

The door to the House of Lords

Wren doorway, Kensington Palace.

The door to Westminster Abbey

St Dunstan’s in the West

The entrance to Christ Church, Greyfriars.

The door to St Bartholomew’s, Smithfield

Temple Church

The Watchhouse, St Sepulcre’s, Smithfield.

Door by Inigo Jones at St Helen’s Bishopsgate.

Prior Bolton’s Door at St Bartholomew the Great.

At the Tower of London

Glass slides courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

East End Women In Colour

These portraits were all taken by Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie for Spitalfields Life over the past eight years. You can see them in Sarah’s exhibition WOMEN OF THE EAST END AT WORK which runs at the Brady Centre in Hanbury St until 30th March as part of Women’s History Month.

Sue Venning, Proprietor, G Kelly Pie & Mash, Roman Rd

Elfet, Garage Mechanic, Three Colts Lane

Anjum Ishtaq, Heba Women’s Project, Brick Lane

Mrs Mustapha, Nazal Dry Cleaners, Hackney Rd

Sandra Esqulant, Publican at The Golden Heart, Spitalfields, and Molly

Shakala, Customer Assistant at Favorite Fried Chicken

Fatima Chowdury, Jumara Noor Eli and Sumsun Nahar Shirna at Mahir Sarees in Bethnal Green

Arful Nessa, Home Machinist, Spitalfields

Laura Porter, Powerlifter, Bethnal Green

Carol Burns, Manager, C.E. Burns Waste Paper Merchants, Spitalfields

Chloe Robertson, Electroplater at Margolis Silver, London Fields

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to take a look at

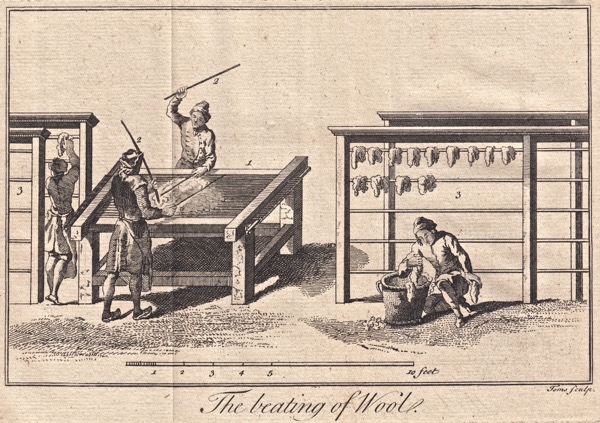

The Principal Operations Of Weaving

These copperplate engravings illustrate The Principal Operations of Weaving reproduced from a book of 1748 in the collection at Dennis Severs House. Many of these activities would have been a familiar sight in Spitalfields three centuries ago.

Ribbon Weaving

Dennis Severs House, 18 Folgate House, Spitalfields, E1

You make also like to read about

Peta Bridle’s Latest Drypoint Etchings

Again, almost a year since has passed since we heard from Peta Bridle, but yesterday she sent me her new drypoint etchings of urban subjects to add to her growing portfolio of people and places in London

The Still & Star, Aldgate – “The pub was opened in 1820 and is the only remaining slum pub in the City of London, converted from a private dwelling. Last year, it was granted Asset of Community Value status but when I returned to give the landlord a print of his pub last autumn I discovered it had closed down. I am not sure what the pub’s fate will be.”

Two Roman Towers, London Wall, City of London –“Next to the Museum of London stands Bastion 14, a surviving section of the London Wall. The ancient Roman and Medieval stones contrast starkly with the new glass towers looming behind. I wonder which tower will still be standing in another thousand years?”

The Late Rodney Archer’s House, Fournier St – “I only had the pleasure to meet Rodney once at his home when I bought a textile print from him.”

The Late Rodney Archer’s Spitalfields Garden

Newham Books – “Run by Vivian Archer, this is a proper bookshop, crammed with books from floor to ceiling. They have been open for forty years this year – Congratulations!”

Bookartbookshop, Pitfield St, Hoxton – “This tiny corner shop sells artists’ books and small press publications”

Richard Lee, Sclater St – “Very obligingly, Richard let me take his photo whilst he was mending a puncture. His stall was originally set up on this pitch by his grandfather, Henry William Lee in the eighteen-eighties. Henry William passed the business on to his son Henry George Lee and now his grandson Richard runs the stall every Sunday in Sclater St Market on the same spot.”

Culpeper’s Herbs – “Here is a selection used by Herbalist Nicholas Culpeper who lived near Puma Court off Commercial St in Spitalfields. Here he ran his clinic and grew herbs to tend the sick in the seventeenth century. From left to right: Dandelion, Campion, Ox-eye Daisy, Buttercup & Ragwort.”

De Walvisch, Wapping – “I first saw this boat when I visited Hermitage Moorings last September over the Open House weekend. Then I contacted the owners and they kindly allowed me to draw their home. De Walvisch means ‘The Whale’ and she is a Dutch sailing Klipper boat from 1896. The boat has retained its original roef (deckhouse) and riveted iron hull. The owners told me that De Walvisch used to deliver eels to London along the Thames.”

Paul Gardner, Gardners Market Sundriesmen, Commercial St – “Here is my new picture of Paul Gardner. He patiently allowed me to draw him again after my last plate of him wore out. When you enter Paul’s shop you can barely move, so only about four people at a time can squeeze in! The shelves bow with the weight of bags and heaped in front of the counter are more bags and balls of string. Paul is a fourth generation Market Sundriesman and his great-grandfather James Gardner opened his shop here in the 1870.”

Waterloo Station – “This is a station I use frequently, and the clock and streams of people caught my eye.”

Waterloo Station – “This is a station I use frequently, and the clock and streams of people caught my eye.”

Crescent Trading, Quaker St – “The last remaining cloth warehouse in Spitalfields. where you can buy fine wool cloths, silks, damasks and cottons, Crescent Trading is run by two dapper gentlemen, Philip Pittack & Martin White. Whenever I visit, they are always beautifully attired in smart suits and ties.”

Shad Thames, Bermondsey – “A riverside street lined with converted warehouses, in Victorian times, these were used to house tea, coffee and spice. When I first moved to London in the nineties you could walk along here and still smell the aroma of spices trapped in the brickwork.”

Gas Holders, Bethnal Green – “Viewed from Mare St, along Corbridge Crescent past Empress Coaches, you see a fine pair of nineteenth century gas holders. English Heritage have decided not to list them and instead granted the owners a Certificate of Immunity against listing, permitting the gas holders to be destroyed and the site redeveloped.”

Blossom St, Norton Folgate – “Running the length of Blossom St are a row of Victorian warehouses built in 1868. Once the headquarters of Nicholls & Clarke they now stand empty, awaiting their fate. This is such a beautiful atmospheric street with its black brickwork and cobbles, I find it inconceivable that a tower block could one day loom in its place.”

Fruit & Wool Exchange, Spitalfields – “Viewed from the top of Spitalfields Market, the dignified Wool and Fruit Exchange stood in Brushfield St since 1927, yet today only a part of the facade remains.”

Phoenix Wharf, Wapping High St – “This beautiful old wharf caught my eye when I was out on a walk. It was built around 1830 and is the oldest wharf in Wapping. Luckily the building itself is not under threat, but the view we have of it now will change forever as the car park opposite is due for redevelopment along with Swan Wharf next door. The developers plan to reduce the Stepney lamppost, the oldest gas lamp left in London, to a stump.”

Oxgate Farm, Cricklewood – “One could easily walk past this without realising what a beautiful building lies behind the scaffolding. Yet once inside it is peaceful and quiet, and modern London is shut off completely. Oxgate Farm has stood here since 1465 and was once part of a thousand acre Manor of Oxgate owned by St. Paul’s Cathedral but now it is reduced to just the farm and back garden. Although Oxgate Farm has managed to survive the centuries, now it badly needs repairs to stop it falling down.”

Archaeological finds from the Bishopsgate Goodsyard – From the left to right – Bone spoon, bone button (top), ceramic wig curler (beneath), green glass phial(top), green glass bottle (beneath), white ceramic spoon (top), pair of ceramic marbles and a child’s bone whistle. (Courtesy of Museum of London Archaeology).

Tiles from the Bishopsgate Goodsyard – “Eighteenth century tin-glazed delftware wall tiles, as used in the fire surrounds of upper and middle class households. On the top left, I like the grumpy expression on the fisherman’s face – probably because he had tangled his line around his companions legs – also, the expressive posture of the couple talking in the meadow below appeals to me, she with her hand on her hip and clutching her bag.” (Courtesy of Museum of London Archaeology)

Gary Arber, W F Arber & Co Ltd – In 2014, Gary closed the print shop opened by his grandfather Walter in 1897 – “Gary is stood next to a Golding Jobber which he told me was used to print handbills for the suffragettes. On his right stands a Supermatic machine and, behind him in the corner, is a Heidelberg which he filled with paper to show me how it worked. The whole room was a confusion of boxes and paper with the odd tin toy thrown in, and lots of string hanging from the ceiling. I feel privileged to have been invited downstairs to make this record of his print shop.”

Spoons by Barn The Spoon – “From left to right: A cooking spoon. A spoon of medieval design. A spoon based on a Roma Gypsy design. The small spoon in the centre is a sugar spoon. A shovel. The large spoon on the right is a Roman ladle spoon. Barn told me the word ‘Spon’ which is carved on the handle is an old Norse word which means ‘chip of wood.’”

Leila’s Shop, Calvert Avenue “- I love visiting Leila’s Shop throughout the year to discover the fresh vegetables of every season, straight from the field and piled up in mouth-watering displays.”

Donovan Bros, Crispin St – “Although it is not a shop anymore I believe Donovan Bros are still producing packaging. I like the muted colours the shop front has been painted and wonder what the shop would have looked like inside?”

Borough Market, London Bridge – “This is the view overlooking Borough Market, looking from the top of Southwark Cathedral tower. The views of London from up there are beautiful but I don’t like the height too much!”

Wapping Old Stairs – “To reach the stairs you have a to go along a tiny passage to the side of the Town of Ramsgate. Originally, the stairs were a ferry point for people wishing to catch a boat along the river. I think they are quite beautiful and I like to see the marks of the masons’ tools, still left on the stones after all this time.”

The Widow’s Son, Bow (now closed for redevelopment) – “The landlady stands holding a hot cross bun in front of a large glass Victorian mirror with the pub name etched onto it. Every Good Friday, they have a custom where a sailor adds a new bun in a net hanging over the bar to celebrate the widow who once lived here, who made her drowned sailor son a hot cross bun each Easter in remembrance.”

E.Pellicci, Bethnal Green Rd – “Nevio Pellicci kindly allowed me to make a couple of visits to take pictures as reference to create this etching. It was at Christmas time and after they closed for the afternoon. Daisy my daughter is sitting in the corner.”

Tanya Peixoto at bookartbookshop, Pitfield St. “I am friends with Tanya who runs this shop and she has stocked my homemade books in the past.”

Des at Des & Lorraine’s Junk Shop, Bacon St – “An amazing place that I want to re-visit since I never got to look round it properly …”

Prints copyright © Peta Bridle

You may also like to take a look at

Geoffrey Fletcher Among The Meths Men

The work of Geoffrey Fletcher (1923–2004) is an inspiration to me, and today I am publishing these fascinating drawings he made in Spitalfields in the nineteen sixties accompanied by an excerpt from his 1967 book Down Among the Meths Men.

If you want to know who they are, the meths men of Skid Row, then I will introduce them as the alcoholic dependents of the East End. They are to be found primarily in an area of of a couple of square miles known as Skid Row. It is a Rotten Row and only beginning to attract the attention of the trend setters.

Skid Row was originally a place of fields. Bodies were tipped there in the plague, their remains turn up occasionally. The most architecturally interesting part of Skid Row are the streets built by the Huguenots, who settled there after the St Bartholomew massacre. A century and a half ago, the rest of the East End surrounded the Huguenot quarter and brought it low. Ultimately the area will be rebuilt. No plans have been made to preserve the houses of Queen Anne’s time, as far as I am informed. I should like to see the whole of Skid Row preserved intact, with its inhabitants, though I recognise this is not a conventional view.

It is necessary, therefore, to contemplate it before it disappears, street by street. Without a doubt, reformers will eventually overtake these suburbs of Hell. They will tear down the fine, rotten houses, build over the bombed site and cart off the wet rags, old mattresses, waste paper and vegetable refuse that makes the quarter so attractive. In that event, London will have lost one of its major advantages, for there is nothing to be gained from well swept streets and office blocks.

Stand in Artillery Lane, watch a meths man rubbing his itchy sores and then eye the stream of commuters pouring into Liverpool St Station intent on the suburbs. Now and again, a meths man will appear among them, a goblin in rags. In their haste for home and respectability, they have nothing to say to him. Nor he to them. He is the inarticulate voice crying from the wilderness of old bricks, bug-ridden rags, cinders and sickly grass. His bloated, alchohol-distorted face is something from an uneasy dream, he sways in front of you in tipsy despair, blurred, disgusting, shaking like an Autumn leaf, the apotheosis of the antihero, a Prophet without a message.

There is a curious camaraderie among the meths men, perhaps the only attractive quality a conventional observer would allow them. It is a ghostly solidarity, the fag end of what is called co-operation, citizenship, the team spirit or any other of those names used commonly to cover up the true nature of the forms of society.

When I got to the Synagogue, I found them on the steps, eight men and a woman. One of the school was in the cooler. A negro roadsweeper languished over his muck wagon at the corner and a few young prostitutes, on the job, hung about in Brick Lane. Brick Lane is marvellous, a melting pot of all the nationalities that grew from the loins of Adam, greasy, feverish Brick Lane, the Bond St for the people of the abyss. Fournier St was a perspective of houses, once the homes of silk merchants and Huguenot weavers, over-used and neglected till the very imposts of the carved doors had become faint and bent with dejection. From the over-tenanted houses, the signs of fruit merchants and Jewish tailors creaked in the wind. The rain had given way to the thin mist of a Winter day.

The Chicksand group sat in a row, staring at nothing. Absolutely nothing. It reminded me of the brass monkeys. I knew the woman. The Chicksand men called her Beth, referring to her native quarter of Bethnal Green. Beth showed signs of recognition, lifted up her weary red eye-lids and stretched out a hand for a fag. I distributed Woodbines. Meths women are heavy drinkers, and can get through three or four wine bottles full in a morning, but they tend to begin slowly and build up as the day wears on. Next to her was Liverpool Jack, an ex-merchant seaman whose nerves had gone West on the convoys, and a man called Pee. He had no other name, nor could any other have done him credit. He was the most abject of the meths men. He had made two or three attempts at suicide, and his last one nearly rang the bell. I thought, sometimes I overdo my relish for offbeat experiences.

In Itchy Park, beside Christ Church, Spitalfields

Meths woman, 1965

Meths men on the prowl in Artillery Passage, 1965

Meths people in Artillery Passage, 1966

Meths men gather round the fire outside the Spitalfields Market

Meths men waiting to move on the corner of Fournier St, 1965

The old meths site in Fieldgate St, Whitechapel

Spitalfields Market scavengers

Meths man asleep in Widegate St, 1965

You may also like to read

James Boswell At The Art Workers Guild

A rare exhibition of James Boswell’s Lithographs & Drawings opens today at the Art Workers Guild, 6 Queen Sq, WC1N 3AT and runs until next Saturday 10th March

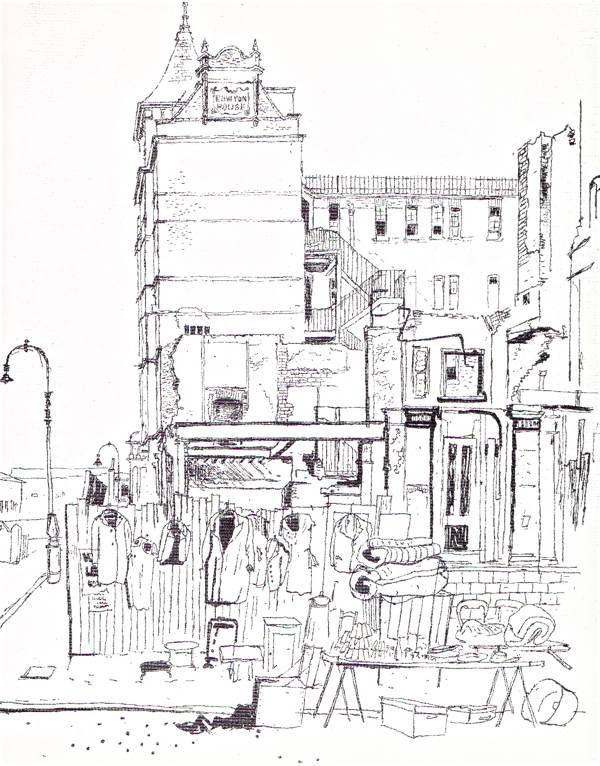

Petticoat Lane in the sixties (Courtesy of David Buckman)

When Ruth Abel met the artist James Boswell (1906-71) in the sixties, he introduced her to the East End. “We spent quite a bit of time going to Bloom’s in Whitechapel. We went regularly to visit the Whitechapel Gallery and then we took a walk afterwards,” she recalled fondly, “James had been going for years, and I was trying to make my way as a journalist and was looking at housing, so we just wandered around together. It was a treat to go the East End for a day.”

“He was in the Communist Party, that was what took him to the East End originally,” she continued, “and he liked the liveliness, the life and the look of the streets, and it inspired him.”

James came from New Zealand to study painting at the Royal College of Art in 1925 and was shocked by the squalor and poverty he found in London. Determined to do what he could to bring about change, he joined the Communist Party after he graduated in 1932 and became a graphic artist, believing that his talent could better serve his political beliefs through painting banners, designing leaflets, and drawing illustrations and cartoons.

Although these pictures of Cable Street and Petticoat Lane were created decades apart and are executed in different styles, they reveal a common delight in human detail, with the inhabitants of the street seeming so completely at home it is as if they and the cityscape are merged into one. Yet, “He did not draw them on the spot,” Ruth revealed to me, as I pored over James’ drawings trying to identify the locations, “he worked on them when he got back to his studio. He had a photographic memory, although he always carried a little black notebook and he would just make few scribbles in there for reference.”

In 1934, James married the artist Betty Soars and then, in 1936, he joined the publicity department of Shell as a means to support his wife and daughter Sal. During the Second World War, James served as a radiographer and continued to draw, documenting all aspects of the conflict as he encountered it in Iraq and then Malta and Sicily. His Communism prevented him from becoming an official War Artist yet his work was acquired by the War Artists’ Committee even though it was not exhibited until 2006. Subsequently, he renounced Communism but remained a Socialist to the end and his graphic works were integral to the successful Labour Party election campaigns of 1945 and 1964.

After the war, James became art editor of Lilliput, a popular literary magazine, where he encouraged many younger artists including Ronald Searle and Paul Hogarth. In 1951, James painted a huge mural for the Sea & Ships pavilion at the Festival of Britain. He was a polymath whose entire working life was occupied by diverse pursuits to make ends meet. In later years, these included editing Sainsbury’s in-house magazine, producing book jackets and illustrations, designing record covers and drawing cartoons for the weekly letters’ page for the Sunday Telegraph. All this was undertaken while filling sketchbooks with drawings done in the street and continuing to paint, exhibiting regularly with the London Group over thirty-five years. In 1966, he separated from his wife Betty and lived with Ruth thereafter

James devoted the last decade of his life to abstract painting. Yet he is chiefly remembered for his influential graphic representations of the East End for Ealing Pictures’ film posters such as It Always Rains on Sunday (1947), The Blue Lamp (1949) and Pool of London (1950), and through his book jackets and illustrations for A Kid for Two Farthings (1953) by Wolf Mankowitz, and A Hoxton Childhood (1969) by A.S. Jasper.

Cable St in the forties (Click image to enlarge)

Pennyfields

Rowton House

Old Montague St, Whitechapel

Gravel Lane, Wapping

Brushfield St, Spitalfields

Wentworth St, Spitalfields

Brick Lane

Fashion St, illustration by James Boswell from “A Kid for Two Farthings” by Wolf Mankowitz, 1953.

Russian Vapour Baths in Brick Lane from “A Kid for Two Farthings.”

James Boswell (1905-1971)

Leather Lane Market, 1937

Images copyright © Estate of James Boswell

CLICK HERE TO BUY A COPY OF A HOXTON CHILDHOOD BY A.S. JASPER ILLUSTRATED BY JAMES BOSWELL

So Long, Vittoria Wharf

Unusual concrete structure with glass block detailing embedded in the roof slab

By the time you read this – barring a miracle – Vittoria Wharf may already be gone. Contributing Architectural Photographer Morley Von Sternberg braved the frost to record these buildings when the builders permitted a final opportunity for access for the last week. He arrived just as they began to remove the roof, thereby exposing the structure as a palimpsest that tells the story of more than a century of manufacturing tradition on this site.

Thus ends one of the most mind-numbing and nonsensical East End planning controversies of recent years, as these well-used buildings are reduced to rubble for the sake of a superfluous new footbridge over the River Lea, linking Hackney Wick and the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, supplementing a pair of existing crossings each within less than two minutes walk.

When the Olympic Authority was created, planning control of the site of the games and surrounding areas was removed from local councils. Afterwards, Boris Johnson set up the Mayor of London’s London Legacy Development Corporation which inherited the power to decide what happened next to this publicly-owned land and property, without the requirement of any democratic accountability. Consequently, although 10,000 signed a petition, 1,300 wrote letters of objection and Mayor of Tower Hamlets John Biggs, Member of Parliament for Bethnal Green & Bow Rushanara Ali and five cross-party London Assembly Members challenged the demolition of Vittoria Wharf, it has gone ahead without any meaningful consultation.

Originally built in 1900 beside the River Lea in Hackney Wick by Vulcanite Roofing Felt, Vittoria Wharf acquired its popular identity when it was named after the mother of one of the proprietors of Byron & Byron Curtain Fixtures. They were the last to use premises for manufacturing before it was compulsorily purchased by the Olympic Authority as part of a large scale buy up of industrial premises.

The 1900 waterfront elevation of Vittoria Wharf with its wall of iron frame warehouse windows conceals extensively remodelling following bomb damage, undertaken in 1947 for Frank F Pershke Ltd, Manufacturers & Importers of Printing Machines. This was by architect Peter Caspari and engineer Felix Samuely, renowned for his work on the De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill. The 20th Century Society commended this work as a “pioneering collaboration” between Caspari and Samuely, whose ingenious reconstruction was at the cutting edge of new architecture as well as making good use of scarce materials.

In 2009, after the departure of Byron & Byron, the premises were converted to around seventy small workspaces and artists studios, along with a cafe and gallery known as Vittoria Wharf & Stour Space, with the following policy – ‘Our vision was to create a forward thinking space that could find new ways of sustaining creativity and innovative business with social value at its core.’ This endeavour was subsequently recognised as a model of grassroots development and granted Asset of Community Value as part of the Localism Act in 2011.

Yet they were evicted last year and an architecturally significant, publicly-owned building in use by a lot of people is being demolished for an unecessary new footbridge and undisclosed future development, in spite of unanimous public opposition. Now the roof is gone from Vittoria Wharf, the lid needs to be taken off the LLDC. Because the entire sorry debacle leaves innumerable pertinent questions unanswered, most obviously – What kind of Olympic Legacy is this?

Photographs copyright © Morley Von Sternberg

[youtube nGVb_q2cUFY nolink]

You may also like to read about