Sights Of Wonderful London

It is my pleasure to publish these splendid pictures selected from the three volumes of Wonderful London edited by St John Adcock and produced by The Fleetway House in the nineteen-twenties. Not all the photographers were credited – though many were distinguished talents of the day, including East End photographer William Whiffin (1879-1957).

Roman galley discovered during the construction of County Hall in 1910

Liverpool St Station at nine o’clock six mornings a week

Bridge House in George Row, Bermondsey – constructed over a creek at Jacob’s Island

The Grapes at Limehouse

Wharves at London Bridge

Old houses in the Strand

The garden at the Bank of England that was lost in the reconstruction

In Huggin Lane between Victoria St and Lower Thames St by Andrew Paterson

Inigo Jones’ gate at Chiswick House at the time it was in use as a private mental hospital

Hoop & Grapes in Aldgate by Donald McLeish

Book stalls in the Farringdon Rd by Walter Benington

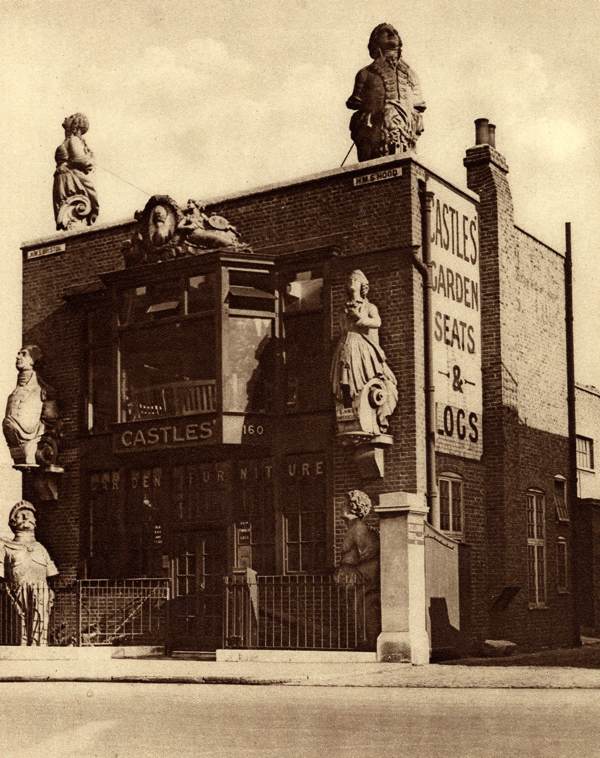

Figureheads of fighting ships in the Grosvenor Rd by William Whiffin

The London Stone by Donald McLeish

Dirty Dick’s in Bishopsgate

Poplar Almshouses by William Whiffin

Old signs in Lombard St by William Whiffin

Penny for the Guy!

Puddledock Blackfriars

Punch & Judy show at Putney

Eighteenth century houses at Borough Market by William Whiffin

A plane tree in Cheapside

Wapping Old Stairs by William Whiffin

Houndsditch Old Clothes Market by William Whiffin

Bunhill Fields

The Langbourne Club for women who work in the City of London

On the deck of a Thames Sailing Barge by Walter Benington

Piccadilly Circus in the eighteen-eighties

Leadenhall Poultry Market by Donald McLeish

London by Alfred Buckham, pioneer of aerial photography. Despite nine crashes he said, “If one’s right leg is tied to the seat with a scarf or a piece of rope, it is possible to work in perfect security.”

Photographs courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

This Is The Year Of Doreen Fletcher

Please make an entry in your 2019 diary to join us at the Private View of Doreen Fletcher’s RETROSPECTIVE at Nunnery Gallery, Bow Arts, on 24th January from 6pm. All are welcome.

This will be a big celebration for the East End and we are seeking a local brewer or distiller to sponsor the event by providing complimentary drinks. If you can help, please get in touch.

I am IN CONVERSATION WITH DOREEN FLETCHER on Wednesday 30th January 7pm at Nunnery Gallery, showing the paintings and telling the stories. Click here for tickets

Salmon Lane in the Rain, Bow, 1987

“It seemed to rain a lot in the eighties. I used to go to Salmon Lane most days since there was a range of shops including a post office, a baker, an off-licence, a butcher, a greengrocers, a dry-cleaner, a laundrette, fruit and veg stall, a pub and two Chinese restaurants – one of which was world famous.

The Good Friends often had Rolls Royces parked outside. I am told Sean Connery, Barbara Streisand and Groucho Marx dined there. Known as The Local Friends, the other Chinese – run by the same family, the Cheungs – was a take-away and it is in my painting. This was excellent so I was never tempted to go to the restaurant, which was not only expensive but the interior was too austere for my taste.”

Corner Shop, Canning Town, 1994

“One Saturday afternoon in June 1991, I visiting an unrewarding jumble sale on the Aberfeldy estate in Poplar. So I decided to explore Canning Town on the other side of the River Lea, ‘the child of the Victoria Docks’ as Dickens termed it.

I followed a black and white collie down him down a street that had been cleared, awaiting redevelopment. The dog turned a corner and had vanished by the time I caught up but I assume he went into the newsagents’ open door. Smelling of firelighters and paraffin, it recalled the corner shops of my childhood in the Potteries,.

This image stayed in my mind so I returned in autumn to buy some sweets in order to view the interior and make some quick sketches, but I was already too late. It was boarded up and I never found out if the dog had gone into the shop.”

Doreen has produced a limited edition print of the Corner Shop available here

Laundrette, Ben Jonson Rd, 2003

“Between 1983 and 1990, when I bought a washing machine, I made the fortnightly trek to the launderette in Salmon Lane. I never had time to sit down and wait for the cycle to run through, so I sometimes paid for the luxury of a service wash. Usually this was when I visited my parents in Stoke.

Two ladies worked in the laundrette. One was more meticulous in her folding technique and I learned to go when she was on duty. Every time I dashed in and out, there was constant chit-chat and the air was blue with the mix of cigarette smoke and steam from the machines. Lil, the good folder, always had a ciggie dangling from the corner of her mouth although I never found any ash on my clothes.

For years I thought about doing a painting, but by the time I got round to it the launderette in Salmon Lane had a face-lift and lost its character. The ladies had retired and the smoky atmosphere had evaporated thanks to red ‘No Smoking’ signs. Then, on a Sunday morning foray to Ben Jonson Road to buy rolls from Wall’s bakery, I spied a couple of legs sticking out from a launderette situated in a parade of shops. I had my subject at last!”

Commercial Rd in the Snow, Limehouse, 2003

“Snow is rare in London and you need to be quick to capture the magic before it turns to slush. When snow fell in late February one year, I was out of the door by eight to survey the crisp, clean landscape. I wandered down the canal until I reached Limehouse Basin but nothing caught my attention. I decided to circle back through the empty streets and I came across this scene at the top of Rotherhithe Tunnel Approach. The sky was a brilliant blue and the snow had transformed the sooty drabness of the Georgian terraced houses to their former elegance.”

Fishmongers, Commercial Rd, Limehouse, 2003

“One clear autumn afternoon, as I was leaving Limehouse Station, I was struck by the sight of the derelict shops in Commercial Rd. I realised this was the site of one of my paintings from thirteen years earlier. I was astonished to find the same parade of shops still standing almost as they were when I depicted them. Back when I painted Brothers the Fishmongers, their sign was still visible and although the building next door was boarded up, the parade of shops was more or less intact. Over several years, squatters moved in and set up a community, making use of the empty space.

I recall painting ‘Fishmongers, Commercial Road’ very clearly because I completed it before I packed away my paints in 2003. I had been teaching part-time for twelve years on special needs and vocational art & design courses. By then, my paintings were no longer shown and, in the prevailing trend, it was difficult to get exposure for my work. When I was offered a full-time post, I decided to accept since I am good at organisation and I enjoyed working with others after so many years alone in my studio.

Two new paintings resulted from my return to Commercial Rd after thirteen years. Both contain the same intense blue sky as ‘Fishmongers,’ a mixture of cerulean and cobalt that you see occasionally in the East End on a fine day. Last year, the squatters were evicted, the parade of buildings was demolished and the site is now a heap of rubble.”

Commercial Rd, 2017

Condemned Shops, 2017

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY OF DOREEN FLETCHER’S BOOK FOR £20

The Last Days Of Shoe Repair

Dave opening up at 7am for the last time at Liverpool St

Just a couple of years ago, there were five places to get your shoes repaired at Liverpool St Station. I barely noticed when the first three disappeared because I always took my shoes to Dave Williams at his booth in Liverpool St. When Dave told me he was quitting on the Friday before Christmas prior to the redevelopment of the terrace, I learned that he would leave only his brother-in-law Gary Parsons at Shoe Key Services – round the corner in the Liverpool St Arcade – as the last man standing. Yet he has also been given notice because his booth is being redeveloped in a year’s time. These are truly the last days of Shoe Repair at Liverpool St Station.

‘I asked about coming back but they don’t want me back, they told me it’s going to be high end only,’ Dave admitted with a frown of disappointment as he swept the pavement outside his shop. For the past twenty years, he has been repairing shoes from seven until six for five days a week at Liverpool St, supplying a vital service with astonishing resilience.

In the week before Christmas, I accompanied Dave through his last days, arriving when he was opening up and sitting in the corner of the booth to observe the rhythm of the day as dawn broke and dusk fell again, as the rush hour ebbed and flowed, as customers brought worn shoes and collected them repaired.

With feverish expertise, Dave worked constantly, repairing several pairs at once – as many as fifty in a day – hammering, sanding, gluing, cutting, spraying and polishing. While waiting for the glue to dry on one pair, he would be tearing the old sole off another and then trimming the new sole once it adhered. Keeping his head down and his eyes on the task, Dave was absorbed in his activity yet maintained a constant stream of banter, thinking out loud. Three generations of skill and craft, and over a century of hard work, culminated in this degree of accomplishment which met its end last week.

In Dave’s stream of thought, those who had gone remained present. ‘My brother-in-law John Holding worked with me here for many years and never had a day off sick but then he went home one day, had a heart attack and died at forty-one,’ Dave confessed in sadness. I sat in the yellow glow of the booth as the afternoon light faded to blue outside where the taxis lined up. ‘They should switch their engines off but they all keep them running ,’ Dave commented over his shoulder, ‘It’s amazing I am still breathing, with the air quality in this booth.’

Dave was constantly interrupted, ceasing work in an instant and emerging from behind the counter to greet each customer and hear their request. There was an intimacy to these conversations, admissions of human failing and fallibility expressed in terms of shoes. Reliably and with magnanimity, Dave delivered his panacea to the worn-out soles of City workers, returning their shoes shining like new. I learned there are many who share the sense of consolation I draw from getting my shoes repaired. In the anonymous City where thousands pass by, the repair booth is an unlikely haven of kindness.

Consequently there were gasps of alarm and disbelief when Dave told his longterm customers of his imminent departure. An accumulating stream of gifts passed over the counter as the week passed away. ‘So many bottles, I could open a bar,’ quipped Dave as he stacked them at the back of the shop.

Dave’s emotions were equivocal. He was angry at the loss of his business, being pushed out by landlords with the insult of replacing his necessary trade by ‘high end’ retail. A community of long-standing small traders in this terrace at Liverpool St, including a jeweller, a barber and a lawyer is no more. Yet after decades of early mornings and long days, Dave is relieved to take a break too. I witnessed these conflicting feelings tempered with visible delight at the appreciation shown by his many long-standing customers. It was a poignant spectacle.

As people came and went, Dave revealed his family history in the business and his plans for the immediate future.

‘My grandfather Henry Alexander Williams was a saddler from Limerick who served in the British army in the First World War. His son Norman, my dad, was born in Ireland and trained as a saddler too but he settled here in the forties. Saddlers and shoe repairers work with the same tools, so he set up as a shoe repairer in Watney St Market and I am the only one of the grandsons who continued with it. Watney St Market was a different place thirty-five years ago, it was a lovely place to grow up.

I had a shop of my own in White Horse Lane and some other places around Stepney Green, but they demolished all the buildings and I could not make it pay. So I have been here since 1998 in Liverpool St, I have worked continuously and I have always made a living.

I do not know what I am going to do after this. My children are grown up, my mortgage is paid off and I have no debts. I have booked a couple of holidays, Jamaica in January, Marrakesh in February and then a wedding in Las Vegas. I will have a few months off. I will be glad of a rest. I would not have done more than another five or ten years if I had been given a choice.

Now it is coming to an end, I think ‘How tedious!’ How could I have been doing the same thing all this time? Yet I have really quite enjoyed it.’

‘You’ve just got to keep picking them up and putting them down’

‘I wouldn’t like to guess how many shoes I’ve done over the years’

‘How can I repay you? You saved my week!’

You may like to read my original story

Charles Goss’ Vanishing City

33 Lime St

A man gazed from the second floor window of 33 Lime St in the City of London on February 10th 1911 at an unknown photographer on the pavement below. He did not know the skinny man with the camera and wispy moustache was Charles Goss, archivist at the Bishopsgate Institute, who made it part of his work to record the transient city which surrounded him.

Around fifty albumen silver prints exist in the archive – from which these pictures are selected – each annotated in Goss’ meticulous handwriting upon the reverse and most including the phrase “now demolished.” Two words that resonate through time like the tolling of a knell.

It was Charles Goss who laid the foundation of the London collection at the Institute, spending his days searching street markets, bookshops and sale rooms to acquire documentation of all kinds – from Cries of London prints to chapbooks, from street maps to tavern tokens – each manifesting different aspects of the history of the great city.

Such was his passion that more than once he was reprimanded by the governors for exceeding his acquisition budget and, such was his generosity, he gathered a private collection in parallel to the one at the library and bequeathed it to the Institute on his death. Collecting the city became Goss’ life and his modest script is to be discovered everywhere in the archive he created, just as his guiding intelligence is apparent in the selection of material that he chose to collect.

It is a logical progression from collecting documents to taking photographs as a means to record aspects of the changing world and maybe Goss was inspired by the Society for Photographing the Relics of Old London in the eighteen-eighties, who set out to photograph historic buildings that were soon to be destroyed. Yet Goss’ choice of subject is intriguing, including as many shabby alleys and old yards as major thoroughfares with overtly significant edifices – and almost everything he photographed is gone now.

It is a curious side-effect of becoming immersed in the study of the past that the present day itself grows more transient and ephemeral once set against the perspective of history. In Goss’ mind, he was never merely taking photographs, he was capturing images as fleeting as ghosts, of subjects that were about to vanish from the world. The people in his pictures are not party to his internal drama yet their presence is even more fleeting than the buildings he was recording – like that unknown man gazing from that second floor window in Lime St on 10th February 1911.

To judge what of the present day might be of interest or importance to our successors is a subject of perennial fascination, and these subtle and melancholic photographs illustrate Charles Goss’ answer to that question.

14 Cullum St, 10th February 1910

3, 4 & 5 Fenchurch Buildings, Aldgate, 28th October 1911

71-75 Gracechurch St, 1910

Botolph’s Alley showing 7 Love Lane, 16th December 1911

6 Catherine Court looking east, 8th October 1911

Bury St looking east, 3rd July 1911

Corporation Chambers, Church Passage, Cripplegate, 31st January 1911 – now demolished

Fresh Wharf. Lower Thames St, 28th January 1912

Gravel Lane, looking south-west, 11th October 1910

1 Muscovy Court, 5th June 1911

3 New London St, 28th January 1912

4 Devonshire Sq

52 Gresham St, 17th September 1911

9-11 Honey Lane Market, Cheapside, 16th October 1910

Crutched Friars looking east from 37, 11th February 1911

Crutched Friars looking east, 28th October 1911

35 & 36 Crutched Friars, 28th January 1912

Yard of 36 Crutched Friars looking north, 11th February 1912

Yard of 36 Crutched Friars looking south, February 11th 1912

Old Broad St looking south, 24th July 1911

Charles Goss (1864-1946)

Photographs courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

and see more of Goss’ photography

Name The Landmarks Of Jewish Spitalfields

Following the success of his Map of Huguenot Spitalfields a couple of years ago, Cartographer Extraodinaire Adam Dant is currently at work on a MAP OF JEWISH SPITALFIELDS and we need your help to compile it.

Click to enlarge Adam Dant’s work-in-progress

Spitalfields was once known as ‘Little Jerusalem’ but today only fragmentary evidence remains of the thriving Jewish community who moved out in the twentieth century. Yet Jewish Spitalfields still exists in living memory and we need you, the readers, to nominate the public landmarks – the synagogues, schools, theatres, cinemas, pubs, shops, restaurants, markets, clubs, housing and more – that defined this lost world, so they can be included on the map.

Please list your suggestions as comments below or you can write to Adam Dant directly at atelierdant@gmail.com . The deadline for submissions is 7th January 2019.

Adam’s Dant’s map takes the form of a mythical placemat from Bloom’s Restaurant in Whitechapel.

Photograph of Bloom’s in Whitechapel High St taken in the seventies by Ron McCormick

You may also like to read these stories

Adverts from the Jewish East End

CLICK TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY OF MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND BY ADAM DANT

Adam Dant’s MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND is a mighty monograph collecting together all your favourite works by Spitalfields Life‘s Contributing Cartographer in a beautiful big hardback book.

Including a map of London riots, the locations of early coffee houses and a colourful depiction of slang through the centuries, Adam Dant’s vision of city life and our prevailing obsessions with money, power and the pursuit of pleasure may genuinely be described as ‘Hogarthian.’

Unparalleled in his draughtsmanship and inventiveness, Adam Dant explores the byways of London’s cultural history in his ingenious drawings, annotated with erudite commentary and offering hours of fascination for the curious.

The book includes an extensive interview with Adam Dant by The Gentle Author.

Adam Dant’s limited edition prints are available to purchase through TAG Fine Arts

Chamberlain’s East End Churches

Click on this image to enlarge

Inspired by this plate of engravings of East End churches in Chamberlain’s History of London, 1770, that I found in the Bishopsgate Institute, I set out on a seasonal walk yesterday to enjoy the winter sunshine and visit these enduring sentinels of the East End. Yet I found myself disappointed upon my journey by the recent loss of characterful landmarks, even as I took consolation from those that survive.

St Anne’s Limehouse

Revelopment of Passmore Edwards Library, Commercial Rd

I wonder how long Callegari’s Restaurant will last?

Imminent facadism on White Horse Lane

The White Horse is gone from White Horse Lane

St Dunstan’s, Stepney

Old Mulberry Tree in St Dunstan’s Churchyard

Tower DIY in Commercial Rd is being redeveloped

St Paul’s the Seaman’s Church, Shadwell

The Old Rose is the last pub standing in the Ratcliff Highway

St George in the East, Wapping

St John’s, Wapping

Parish School 1780, Wapping

St Mathew’s, Bethnal Green

Archive images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

Fritz Wegner’s Christmas Plates

I discovered my delight in the work of illustrator Fritz Wegner (1924-2015) in primary school through his drawings for Fattypuffs & Thinifers by Andrew Maurois. Throughout my childhood, I cherished his book illustrations whenever I came across them and the love of his charismatically idiosyncratic sketchy line has stayed with me ever since.

Only recently have I learnt that Fritz Wegner was born into a Jewish family in Vienna and severely beaten by a Nazi-supporting teacher for a caricature he drew of Adolf Hitler at the age of thirteen. To escape, his family sent him alone to London in August 1938 where he was offered a scholarship at St Martin’s School of Art at fourteen years old, even though he could barely speak English.

A few years ago, I came across this set of small souvenir Christmas plates Fritz Wegner designed for Fleetwood of Wyoming between 1980 and 1983 in limited editions, which I acquired for almost nothing. They are crudely produced, not unlike those ceramics sold in copyshops with photographic transfers, yet this cheap mass-produced quality endears them to me and I set them out on the dresser every Christmas with fondness.

Journey to Bethlehem, 1983

The Shepherds, 1982

The Holy Child, 1981

The Magi, 1980

You may also like to take a look at