From Viscountess Boudica’s Album

A tender scene from the childhood of Viscountess Boudica

For years, Viscountess Boudica wrote an autobiography – absurd, bawdy and magical by turns – in daily installments. Entitled There’s More to Life than Heaven & Earth (sadly now discontinued), it was like nothing else on the internet. One day, the Viscountess and I met for a chat to take stock of her brave endeavour and select a few key excerpts.

“The blog is like justice in a way,” she confided to me. Ascribing her storytelling instincts to her Celtic roots, Viscountess Boudica is a latter-day Mother Goose, intertwining poignant tales of lost love with unexplained visionary encounters and broad comic stories to weave a mythological universe that is entirely her creation.

With an unerring instinct for the ironies of existence, Boudica reconciles herself to the painful contradictions of life by taking fearless narrative delight in personal humiliations others might choose to forget. Viscountess Boudica understands she can advance herself in actuality through becoming the author of her own story.

My clothes designing started down on the farm at five years old, when I was taking care of the pigs, Paul & Keith. When the cats were expecting, I used to hide them in the barn so my uncle wouldn’t drown them. They were all feral and interbred. I used to make clothes for the kittens and they lay in a pram which I used to wheel around the village. I tried to dress the pigs too, but it didn’t quite work out because they ripped them off and rolled in the mud.

Paul O’R, when I first met him, I asked if he was an Aries. So the second time I met him I took him a chocolate biscuit and – you know what – he said, “You look lovely,” and he bowed his head and I stroked his hair.

The Monks of Moreton. The engine of my car stopped and I saw all these monks crossing the road to the abbey. Apparently, it’s a well-known local sight.

Whatever happened to the old English sayings? They just don’t say, “What ho!” anymore, except in period films.

Paul B. said, do I fancy going to a barbecue and off we went to the wilds of Colchester. He was barbecuing sausages and there were four on the grill at one pound each. The one in the middle looked under-done and I am sure it winked at me. So I grabbed it to put some mustard on it and as I pulled it Paul’s eyes were watering.

Paul S., a white South-African, I met him in 1995 at Tesco in Tollerton. He’d had a row with his boyfriend and said, “Could you put me up for a couple of days?” As a present, he got me some flours as a joke when I expected flowers. Eventually, his boyfriend came to pick him up but they didn’t think it was so funny when I poured the flours over them.

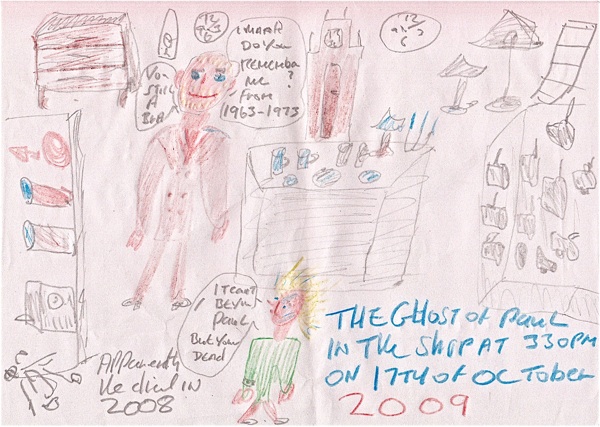

I went into Des & Lorraine’s Shop in Bacon St and it was full of people. Then as I looked where Des was standing, I thought I’d seen this bloke somewhere before. It was quarter past three and my watch stopped and everything stopped and the man said to me, “Do you remember who I am? Do you remember that day in 1965 when you got banned from the farm?” It was Farmer Paul and recalled I used to sit on his lap as a child and I could feel something hard, and he used to put his hand on my chest and say, “It’s getting bigger.” He said to me, “Something’s going to happen, you’ll find out.” I ran out through the shop and my watch dropped on the pavement. He followed me and said, “I will come for you when you die.” So then I went home and rang Chris from Southend, and when he said his mother died at 3:15pm, I realised I had experienced some kind of vision.

One time, I went to Braintree Freeport to sell some photos and this sexy bearded train driver walked past the carriage.

There was this brickie called Eric in Braintree and he told me about this cottage on the A12, and I imagined a cottage with a thatched roof and roses round the door. But when I asked if I could come, he said, “It’s strictly for boys and we have prayer meetings.” So when I passed my driving test, I went to find this mystery building, but it wasn’t until years later that I discovered it was a public toilet.

My friend Ted in Braintree worked for the BBC and had a love of Islington, so he moved back to Finsbury Park and then Bounders Green. Four years later, after I moved to London on Halloween 1994, he was dead. Then, five years ago, I got on a train at Cambridge Heath and this guy got on at Seven Sisters and sat opposite me and smiled. He pulled out an old square mobile phone with an aerial and he kept looking at me. At Bruce Grove, he was gone, so I ran down the stairs and he was there. He said, “You remember who I was? There’s more to LIfe than Heaven & Earth.”

For thirteen years, I visited Keith at Lordship Cookers and held his hand outside the shop. That went on for years and I bought all these dodgy makes that never worked.

Now I’ve let go of the past, I’ve destroyed my diaries and got rid of my cookers but I’ll always have my memories. Since I changed my kitchen I got one of those ranges, because I’ve accepted that the Tricity 643 will never come.

The last time I saw Paul O’R from Sclater St was in 2009 on 21st December, and I went home and put his present under the tree but he never came to get it. Maybe this year?

Viscountess Boudica with the Christmas present she has kept awaiting its recipient for the past three years. Like the spirit of Christmas Present, Boudica always travels with a fully decorated tree in the festive season.

You my also like to read my other stories about Viscountess Boudica

Viscountess Boudica’s Domestic Appliances

From Henrietta Keeper’s Album

Henrietta Keeper, Singer

Henrietta Keeper (widely known as “Joan”), the vivacious octogenarian ballad singer who used to perform at E.Pellicci in the Bethnal Green Rd on Fridays, once invited me to round to her tiny flat to show me her remarkable collection of photographs and meet her daughter Lesley, custodian of the family album.

These pictures show Henrietta’s life as it existed within a small corner of the East End on the boundary of Spitalfields and Bethnal Green in the nineteen fifties. On one side of Vallance Rd was Cranberry St where Henrietta’s mother-in-law Selina lived and took care of her daughters while the family waited for a house of their own. On the other side of Vallance Rd was Selby St where Henrietta’s husband Joe and his brother Jim ran Keeper & Co, making coal deliveries. And at the end of Vallance Rd was New Rd where Henrietta worked as a machinist at Bartman & Co making coats and jackets.

Having grown up in Bethnal Green during the war and brought her own family up though the austerity that followed, Henrietta was a woman of indefatigable spirit. Most remarkable of all, she sang throughout her life, winning innumerable singing competitions and giving free concerts.

Henrietta with fellow machinist Izzie. “When I was nineteen I started here and I became the top machinist,” she explained, “I think my hair looks a bit like Barbara Windsor’s in this picture.”

Henrietta with Mr Bartman at Bartman & Co.

“This is Selina Keeper, my mother-in-law at her house in Cranberry St. She was real Victorian lady. She used to whip the cup of tea off the table before you had finished it!” said Henrietta. And Lesley added, “She had a best front room that she kept under lock and key, and only once – when she unlocked it – did I go in, but she said ‘Get out!’ You couldn’t touch anything. It had to be kept perfect.”

“My husband Joe took this picture of his two best friends George Bastick and Leslie Herbert in Nelson Gardens next to St Peter’s Church, Bethnal Green. What a pity he isn’t in it?”

Coronation Day, 1953, celebrated at Hemming St, Bethnal Green. Lesley is in the blazer on the right hand side of the front row and Henrietta can be distinguished by her blonde hair beneath the Union Jack, peering round the lady in front of her.

“This is Jim Keeper, my brother-in-law, with his horse Trigger. My husband, Joe, worked with him and he had the biggest coal round in the East End – Keeper & Co. Joe was so strong he could carry a two hundredweight sack of coal on his back up the stairs of the buildings with ease. The brothers used to go home to lunch with their mum in Cranberry St and take Trigger with them. She always collected the horse manure for her roses while they were there and when the Queen Mother visited the East End, she leaned over the fence and said ‘This one should win best garden.'”

“Taken in 1947 at Southend, when I was twenty, this is Cathy Tyler, my sister Marie and me – I was known as Minxie at the time and we all sang together like the Andrews sisters. I was a bit shocked when I saw it because you can see I am pregnant. I thought, ‘Is that me?'”

Henrietta (far right) photographed with her workmates by a street photographer around Brick Lane during a lunch break in the fifties.

This is Henrietta’s daughter Lesley visiting Petticoat Lane with her grandfather James Keeper in 1953. “He was a delivery man with a horse and cart, they called it a ‘carman,'” Henrietta remembered, “he was also a cabinet-maker and he brought me beautiful polished wooden boxes that he made.”

Henrietta and her husband Joe with their daughter Lesley on a trip to Columbia Rd.

The two children on the right are Lesley and Linda Keeper playing at Cowboys and Indians with their friends in the nineteen fifties in Cranberry St while they lived with their grandmother. Lesley remembers Mrs Dexter across the road who called out “Play nicely on the debris!” to the children and you can see the bomb site where they played in the back of the photograph. Today Cranberry St no longer exists, just the stub of road beside Rinkoff’s bakery in Vallance Rd indicates where it once was.

Henrietta singing at a Holiday Camp at Selsey Bill in the nineteen sixties.

Henrietta singing at Pelliccis

You may like to read my original portrait

From Clive Murphy’s Album

I am celebrating my friend, the late Clive Murphy, by publishing his snaps

Pauline, Animal Lover, 77 Brick Lane, 16 July 1988

When it cames to photography, Clive Murphy – the novelist, oral historian and writer of ribald rhymes – modestly described himself as a snapper. Yet although he used the term to indicate that his taking pictures was merely a casual preoccupation, I prefer to interpret Clive’s appellation as meaning “a snapper up of unconsidered trifles” – one who cherishes what others disregard.

“I carried it around in my shoulder bag and if something interested me, I would pull out my camera and snap it,” Clive informed me plainly, “I am a snapper because I work instinctively and I rely entirely upon my eye for the picture.”

In thousands of snapshots, every one labelled on the reverse in his spidery handwriting and organised into many shelves of numbered volumes, Clive chronicled the changing life of Spitalfields, of those around him and of those he knew, since he came to live above the Aladin Restaurant on Brick Lane in 1973. These pictures are not those of a documentary photographer on assignment but the intimate snaps of a member of the community, and it is this personal quality which makes them so compelling and immediate, drawing the viewer into Clive’s particular vivid universe in Spitalfields.

One day, we pulled out a few albums and leafed through the pages together, selecting a few snaps to show you, and Clive told me some of the stories that go with them.

Brick Lane, May 1988

Komor Uddin, Taj Stores, 7 December 1990

Columbia Rd Market, 13 November 1988

Jasinghe Ranamukadewasa Fernando (known as Vijay Singh), Holy Man with acolyte, Brick Lane, March 1988 – “Many people in Brick Lane thought he was the new Messiah and the press came down in droves. He was regarded as a very holy man, he held court in the Nazrul Restaurant and people took his potions and remedies. When he died, I joined the crowd to see his body at the Co-op Funeral Parlour in Chrisp St.”

Clive Murphy’s cat Pushkin, 132 Brick Lane, July 1988 – “Pushkin followed me down Brick Lane from Fournier St one night and, when I opened my hall door, he came in with me. So he adopted me, when he was only a kitten and could hardly jump up a step. And I had him for twenty years.”

Neighbour’s doves hoping to be fed, 16 March 1991 – “The Nazrul Restaurant used to keep doves and, when they disappeared, Pushkin was blamed but I assure you he had nothing to do with it.”

Kyriacos Kleovoulou, Barber, Puma Court, 23 February 1990 – “I’ve had a few haircuts there in the past.”

Waiter, Nazrul Restaurant, Brick Lane, 29 May 1988

Harry Fishman, 97 Brick Lane, 19 September 1987 – “He was a godsend to everybody because he cashed any cheque on the spot. I think he was used to being robbed, so he wanted to get rid of the cash. Harry Fishman was the most-loved man on Brick Lane in the seventies, his shop was always full of people wanting to be around him, and I often delivered papers to The Golden Heart for him.”

Harry Fishman’s shop, corner of Quaker St, 19 September 1987

Window Cleaning, Woodseer St, March 1988 – “This man used to run an orchestra and, at all dances and Bengali events, they would play.”

Sunday use of Weinbergs (sold), November 1987 – “It was a printers and when it closed it became a fruit stall. Mr Weinberg was a very jolly fat man, slightly balding, who ordered his staff about. He would say things like, ‘Left, right, left, right, do it properly!’ I dined at his house and I didn’t like the cover of my first novel, so I asked him to redesign it for me. He had a nephew who had never been with a woman and he asked me to find him an escort agency. We all dined in a restaurant behind the Astoria Theatre in the Charing Cross Rd, and then I let them use my front room. But after an hour she came out and said, ‘It’s no use, I give up!’ but we still had to pay, and his nephew never became a man.”

Christ Church Night Tea Stall, October 1987 – “I always went out as the last thing I did before I went to bed, to have a snack.”

Clive’s landlord, Toimus Ali, at The Aladin Restaurant, 6 March 1991 – “He was very taciturn.”

Fournier St, 7 February 1991 – “I used to come here and have lunch with all the taxi-drivers who loved it so much.”

Retired street cleaner, Brick Lane, March 1988

Tramp, Brick Lane, 29 May 1988

Pushkin unwell, Jan 4 1991 – “I was told it would be quite alright to feed my cat on frozen whitebait, but I didn’t thaw it properly and it killed my Pushkin.”

Harry Fishman’s shop after closure, 97 Brick Lane, 27 September 1987

Clive at his desk, 132 Brick Lane, 31 December 1989

Photographs courtesy of the Clive Murphy Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to read my other stories about Clive Murphy

From Andy Stroman’s Album

Andy Strowman, poet of Stepney, sent me these photos and the stories which accompany them.

Uncle Dave

Uncle Dave came to visit us from time to time. Maybe my mum knew in advance, it was like having royalty come to see you.

One time he came over during his work lunchtime and my mum made him something to eat, like chicken soup. I told him I was going back his way, so we went together to Whitechapel Station. He was just about to get off at Aldgate East Station when I announced that I was going for a job interview.

“Shush!” he said,” Someone will get there before you!’

“Before you go in, take your raincoat off and fold it neatly draped over your arm.”

I got the job! It was only washing up, but Uncle Dave gave me the confidence.

Another time, when Uncle Dave and I had not long left the synagogue on the holiest night of the year, the Jewish New Year, in Hebrew Rosh Hashonah, a drunk man approached us, and his stormy face and mad rolling eyes made me, a boy of about eight, very frightened.

Uncle Dave pointed upwards at the night sky with its dazzling stars like a Van Gogh painting and uttered, “Look! Look up there!” As the drunk man searched the sky, Uncle Dave pulled my arm and we escaped.

When seventeen, that came in very handy in rescuing me from peril.

Bar Mitzvah

My mum and dad were so excited, they hired caterers to come to our poor house in Milward St. I had never seem so much food and drink for our family and guests in my life. Before the event, the synagogue service and all the family guests, the news was published in the Jewish Chronicle.

My mum was frantic, it was a lot of stress. My grandfather who lived in Boston, Massachusetts, and was originally from Ukraine came over for the bar mitzvah.

My friend and I sat on the stairs while all the grown-ups drank and talk. So much noise, it was like a wood-machining factory.

Uncle Jack

I like to remember the happy stories associated with him, like meeting my two young sons with giant Cadbury’s dairy milk bars. His generosity, such as when my mum was in hospital in Epsom, one of the patients needed their trousers mended and my uncle volunteered to do it, and brought them back to him.

His generosity was amplified by my friend Alan. Both were compulsive gamblers. After visiting the racecourse, Alan got off at Charing Cross main line station, a woman approached him and asked him for money. She said she was in a desperate state, so he gave her generously and she wanted to repay him.

One sunny day, Alan was sitting on a bench in Soho when this same woman came and repaid him.

Auntie Tina

Mental health can be a cruel teacher. Sadly, both my mum, Auntie Tina (Uncle Jack’s wife), Uncle Barney, and myself, have all had our share of it. Some can be attributed to circumstances, others to inherent cause but Auntie Tina had both.

Living in a high rise block of flats with disturbing neighbours nearby, being spat at in the lift, social isolation, can only lead to one thing. Her life was shorted much like Uncle Barney’s was.

Tina had come from Lisbon and had known more graceful days. The epiphany of lack of caring support and people hardly knowing neighbours, the ultimate question being, “Who could you ask among them if you have a serious problem?”

Reg & Valerie Parrish

Reg entered Bergen-Belsen concentration camp as part of the liberating forces. After what he saw there, all the dead bodies and Jewish people looking like skeletons, he vowed never to have any children and bring them into this world. Reg kept his word.

His sister, I believe her name was Valerie, was a member of ENSA, that entertained army troops during the war. She said, “We often ran the same risk as the soldiers in the war, and were caught up in shooting and bombing raids.”

Mum & Dad

My mum and dad were among the black cab taxi drivers who took children to the seaside for the day. These were children from care homes. In their case, the children were from Norwood Jewish care home.

The taxis were festooned with balloons and travelled as a long convoy to the seaside. There they had a good time – the children were fed and no doubt got an ice cream! I must admit to being jealous as going to the seaside was such a rare treat. To this day, the event still takes place by London taxi drivers. The Norwood home is I believe now closed though.

You may also like to read about

At Goldsmiths’ Hall

The Leopard is the symbol of the Goldsmiths’ Company

Whenever I walk through the City to St Paul’s, I always marvel at the great blocks of Hay Tor granite which form the plinth of this building on the corner of Gresham St and Foster Lane. Goldsmiths’ Hall has stood upon this site since 1339 and the current hall is only the third incarnation in seven hundred years, which makes this one of the City’s most ancient tenures.

The surrounding streets were once home to the goldsmiths’ industry in London and it was here they met to devise a system of Assay in the fifteenth century, so that the quality of the precious metal might be assured through “Hallmarking.” The origin of the term refers to the former obligation upon goldsmiths to bring their works to the Hall for Assaying and marking and, all these years later, Goldsmiths’ Hall remains the location of the Assay Office. The leopard’s head – which has always been the mark of the London Assay Office – recalls King Richard II, whose symbol this was and who granted the company its charter in 1393.

Passing through the austere stone facade, you are confronted by a huge painting of 1752 – portraying no less than six Lord Mayors of London gazing down at you with a critical intensity. You are impressed. From here you walk into the huge marble lined stairwell and ascend in accumulating awe to the reception rooms upon the first floor, where the glint of gold is everywhere. The scale of the Livery Hall is such that you do not comprehend how a room so vast can be contained within such a restricted site, while the lavish panelled Drawing Room in the French style with its lush crimson carpet proposes a worthy stand-in for Buckingham Palace as a location fir filming, and exists just on the right side of garish.

A figure of St Dunstan greets you at the top of the stairs, glowing so golden he appears composed of flame. A two thousand year old Roman hunting deity awaits you the Court Room, dug up in the construction in 1830. A marble bust of Richard II broods upon the landing, sceptical of your worthiness to enter the lofty company of the venerable bankers and magnates whose names adorn the board recording wardens stretching back to the fourteenth century. In every corner, portraits of these former wardens peer out imperiously at you, swathed in dark robes, clutching skulls and holding their council. I was alone with my camera but these empty palatial rooms are inhabited by multiple familiar spirits and echo with seven centuries of history.

St Dunstan is the patron saint of smiths

The four statues of 1835 by Samuel Nixon represent the seasons of the year

Staircase by Philip Hardwick of 1835

William IV presides

The figure of St Dunstan holding tongs and crozier was carved in 1744 for the Goldsmiths’ barge

Dome over the stairwell

Richard II who granted the Goldsmiths their charter in 1393

The Court Room

Philip Hardwick’s ceiling in imitation of a seventeenth century original

Roman effigy of a hunting deity dug up in 1830 during the construction of the hall

The Drawing Room

Clock for the Turkish market designed by George Clarke c.1750

Eleven experts worked for five months to make the Wilton carpet

Ormolu candelabra of 1830 in the Drawing Room

The Drawing Room, 1895

Mirror in the Livery Hall

The Livery Hall

The second Goldsmiths’ Hall, 1692

The current Goldsmiths’ Hall, watercolour by Herbert Finn 1913

Benn’s Club of Alderman, 1752 – containing six Lord Mayors of London

You may also like to read about

The Spitalfields Roman Woman

Curator of Human Osteology, Rebecca Redfern watches over her charge

In his Survey of London 1589, John Stow wrote about the discovery of pots of Roman gold coins buried in Spitalfields and it had long been understood that ancient tombs once lined the road approaching London, just as they did along the Appian Way in Rome. Yet it was only in the nineteen-nineties, when large scale excavations took place prior to the redevelopment of the Spitalfields Market, that the full extent of the Roman cemetery was uncovered.

In March 1999, a Roman stone sarcophagus containing a rare lead coffin decorated with scallop shells came to light, indicating the burial of someone of great wealth and high status. Grave goods of fine glass and jet were buried between the coffin and the sarcophagus. It was the first unopened sarcophagus to be found in London for over a century and when the entire assemblage was removed to the Museum of London, the coffin was opened to reveal the body of a young woman in her early twenties, buried in ceremonial fashion. In the week after the opening of the coffin, ten thousand Londoners came to pay their respects to the Spitalfields Roman woman. She was the most astonishing discovery of the excavations yet, as the years have passed and more has been learnt about her, the enigma of her identity has become the subject of increasing fascination.

Analysis of residue in the coffin revealed that her head lay upon a pillow of bay leaves, her body was embalmed with oils from the Arab world and the Mediterranean, and wrapped in silk which had been interwoven with fine gold thread. Traces of Tyrian purple were also found, perhaps from a blanket laid over the coffin. Such an elaborate presentation suggests she may have been displayed to her family and friends seventeen hundred years ago as part of funeral rites.

The sarcophagus and grave goods are on public exhibition at the Museum but, thanks to Rebecca Redfern, Curator of Human Osteology, Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie and I had the privilege to visit the Rotunda where the human remains are stored and view the skeleton of the Spitalfields Roman woman. Deep in a windowless concrete bunker filled with metal shelving stacked with cardboard boxes, containing the remains of thousands of Londoners from the past, lay the bones of the woman. We stood in silent reverence with just the sound of distant traffic echoing.

Rebecca is the informal guardian of the Spitalfields woman and remembers switching on the television to watch news of the discovery as a student. Today, she has a four-year-old daughter of her own. “The work went on for so many years that a lot of couples met working in Spitalfields,” Rebecca admitted to me, “and there is now a whole generation of ‘Spital babies’ born to those archaeologists.”

“She’s five foot three and delicately built, petite like a ballet dancer,” Rebecca continued, turning her attention swiftly from the living to the dead and gesturing protectively to the bones laid out upon the table. While some might objectify the skeleton as a specimen, Rebecca relates to the Spitalfields Roman woman and all the other twenty thousand remains in her care as human beings. “They’re able to tell us so much about themselves, it’s impossible not to regard them as people,” she assured me.

Recent research into the isotopes present in the teeth of the Spitalfields Roman woman have revealed an exact match with those found in Imperial Rome, which means that her origin can be traced not just to Italy but to Rome itself. “I find it very sad that she came so far and then died so young,” Rebecca confided, recognising the lack of any indication of the cause of death or whether the woman had given birth. Contemplating the presence of the skeleton with its delicate bones dyed brown by lead, it is apparent that the Spitalfields Roman woman holds her secrets and has many stories yet to tell.

More than seventy-five Roman burials were uncovered at the same time as the sarcophagus, many interred within wooden coffins and some only in shrouds. You might say these represented the earliest wave of immigration to arrive in Spitalfields.

“People were so mobile,” Rebecca explained to me, “We found a fourteen-year-old girl from North Africa whose mother was European. A legion from North Africa was sent to guard Hadrian’s Wall and we have found tagine cooking pots that may been theirs. I pity those men – how they must have suffered in the cold.”

The only Roman sarcophagus discovered in London in our time was uncovered in Spitalfields in 1999

Inside the stone sarcophagus an elaborately decorated lead coffin was discovered

At the Museum of London, the debris was removed to uncover the pattern of scallop shells

The lead coffin was opened to reveal the body of a young woman

Photographs of coffin & excavations copyright © Museum of London

Portrait of Rebecca Redfern & photographs of skeletal details copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

St John At Spitalfields City Farm

Produce from Spitalfields City Farm

One of my great delights of 2024 was introducing Farokh Talati, Chef at St John Bread & Wine to Chris Gorgay, Grower at Spitalfields City Farm with the result that fresh produce from the farm has become an integral part of the menu at St John, where you can now enjoy vegetables grown locally and picked fresh that morning. The farm is just six minutes walk from the restaurant in Commercial St and almost every day a chef visits to select what is in season.

At harvest time last year, I accompanied Farokh and Chris on a tour around the vegetable patch and Contributing Photographer Patricia Niven came along too. Chris introduced us to his cherished produce, regaling us with the stories of their origin and cultivation while inviting us to enjoy the variety of fragrances, and taste the leaves and fruit of his plants as we made our way around the farm.

Chris’ vegetable patch is not ordered into straight lines upon bare soil, he grows his vegetables close by each other interspersed with flowers to create a beautiful grove of dense foliage where plants flourish. ‘We use marigolds as companion planting to distract aphids from the vegetables but also to attract pollinators,’ he told me, explaining his method. ‘What you plant in your growing space can really affect how much it’s going to be impacted by pests. We let some vegetables go to flower so we can harvest the seeds for next season and that attracts more beneficial insects too.’

Chris plants crops in rotation to renew the soil. ‘Potatoes take quite a lot of nutrients out of the earth which is why we will follow them the next year with chard, which is not a very heavy feeder, and replenish the soil with manure too.’

‘Here at the farm, we teach local kids how to grow vegetables and maintain their crops. Then they get to harvest and cook them, so they get the all round experience. We teach them how to save their own seeds too, so they have a sustainable approach to gardening.’

When Farokh asked if cucumbers were part of the same family of plants as melons, Chris replied in the affirmative. ‘You can often tell by the seeds, because the seeds of one genus of plants often look very similar – melon, squash and cucumber seeds look alike,’ he said.

As we made our way around, with Chris explaining the culinary potential of each of his varieties, I could see Farokh’s eyes lighting up in inspiration as Chris suggested ways that he could employ these vegetables in his cooking – which in turn became a source of wonder and delight for Chris.

‘Every time I come here I learn something new!’ Farokh declared to me. ‘I’ll go over to the farm once a week, chefs will go on other days, and Chris delivers produce maybe twice a week. And we’re always talking to each other, Chris will send me a picture of something that’s coming up soon. I’ve been over with Trevor Gulliver and Fergus Henderson too.’

‘For me it’s important for St John to have a strong sense of connection with the community and the joy that it’s given us to use this farm, and to know that we can go over there and say, ‘Can we grab this?’ or ‘Can we grab that?’ or for them to come over and put their produce down on the table in front of guests. People will be eating their lunches and in walks Chris with onions, fresh garlic and mulberries and it’s such a proud moment.’

‘It’s rare in London restaurants. In many places I’ve worked the produce is there in the morning in boxes and you can forget where it came from. I have a huge sense of pride when I brief the waiters to say, ‘This dish has come from Spitalfields City Farm and I want you to talk about it at the table.’ How proud we are to announce, ‘These were picked this morning at the farm down the road.’

Honey melon

Sweetcorn

White aubergines – the origin of the name ‘egg plant’

Runner beans

Basil and chillies

Chris Gorgay, Grower

Marigolds and tomatoes as combination planting

Marigolds and tomatoes as combination planting

Farokh Talati, Chef

Mulberries

Melons

Farokh uses fig leaves to flavour ice cream and buttermilk pudding

Fig leaf, radish and cucumber

Kudu, a bottle gourd grown from seeds brought from Bangladesh twenty five years ago

Photographs copyright © Patricia Niven

Vegetables can bought direct from the Farm Shop at Spitalfields City Farm, Buxton St, London E1 5AR

You may also like to take a look at

Spring at Spitalfields City Farm

Summer at Spitalfields City Farm