Kevin Boys, Blacksmith

Last chance! Only a few tickets left for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S WALKING TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS on Sunday October 3rd at noon. Email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com to book.

Map of the Gentle Author’s Tour drawn by Adam Dant

Join me on a ramble through Spitalfields taking less than two hours, but walking through two thousand years of history and encountering just a few of the people who have made the place distinctive.

Click here for further information

Kevin Boys, Blacksmith

At the eastern extent of Rotherhithe, there is a tumbledown shack open to the elements where blacksmith Kevin Boys works at his anvil each day from seven every morning. A century ago, this was a receiving station where smallpox victims were wheeled in from ambulances before embarking onto quarantine vessels, but today it is the only old building amongst a sea of recent construction and sits in the midst of an overgrown city farm.

Yet this rural anachronism reminds us of Rotherhithe’s agricultural past, while the ringing of Kevin’s hammer would once have been a familiar sound in the shipyards that superseded it which have, in turn, been supplanted in the last generation by new housing.

There was soft rain falling on the morning I paid my visit to Kevin’s magnificent shed with a forge of hot coals at the centre, illuminating the interior with a golden flickering light and drawing my attention to the vast array of different varieties of rusty tongs and other iron-working tools acquired in the twenty-five years he has been working here. In his battered hat and old leather waistcoat, Kevin worked with relaxed concentration to shape a piece of hot iron with his hammer, sending a loud clanging resounding around the damp farmyard.

“Beware of sparks!” he warned me as I leaned over with my camera.

“I learnt blacksmithing off my grandfather Edwin Thurston, he worked as a blacksmith on the railways in Kent during the thirties and it was his brother Leopold who came up to London. When I was younger, I was interested in sculpture and printing, so when I left school in Bournemouth I did a foundation course followed by a degree in Fine Art & Sculpture at Canterbury. That was where I started blacksmithing and, from there, I came up to London to work with Jeff Love & John Gibbons at their studio in Woolwich, making sculptures in steel. But, after a year, I got the opportunity to do post-graduate study in Baltimore.

I returned to London 1984 and set up my first forge off the Old Kent Rd in 1985, where I started working as blacksmith, making things like candlesticks and furniture. I did commissions for Paul Smith and Joseph Ettedgui, and sold my work through the Fiell Gallery in the King’s Rd. Then I moved to Deptford to one of the railway arches next to station – my lighting and furniture business was kicking off and I did a lot for the South Bank Centre.

In 1991, I came to Rotherhithe. The whole area was desolate then but the farm had already been here a few years. Since then, I have been making gates, doing interior design, manufacturing furniture and sculpture – I did the angel at the Angel Tube Station. All this time, I have been working continuously, it has been non-stop.

It was my job to recreate the torture equipment from about 1580 for the Tower of London. I made the stretching rack, ‘the scavenger’s daughter’ and some manacles. It was an amazing job to get. Although I did a lot of research, the only image of a rack I found from this era was a decoration on the inside of an edition of Shakespeare but from this engraving we were able to reconstruct it. We got the oak rollers made down in Dorset and the rope was manufactured at Chatham Dockyard.

The Constable of the Tower asked me to make a speech, so I had to think on my feet and stand up in front of three hundred people at the unveiling. It turned out to be quite a macabre speech, not because of what I said but because, when we started ratcheting up the rack, it made a rather horrible clanking sound, which had an hypnotic impact upon the crowd.

I especially like the design side of things, but blacksmithing involves a huge range of activities from blade-smithing to historical restoration and recreation. Doing all these different jobs allows you to become very experienced.

The future of blacksmithing lies in sculptural design for interior and exterior projects, and in historical recreation. There are blacksmithing courses available and the level of skill is fantastic now. I have three apprentices today. The difficulty lies in making things that people want to buy. We do mostly commissions and we go into schools with a mobile forge doing demonstrations. All the kids do hot metal work and we often make something for the school, at St Luke’s in the East End we made a sculpture of Christian from Pilgrim’s Progess.”

Kevin Boys’ forge was originally constructed in 1884 as a receiving shelter for ambulances delivering smallpox patients to quarantine ships moored off Rotherhithe

Kevin Boys, Blacksmith

Kevin’s forge

You may also like to read about

Spitalfields Nippers

All my tours are sold out now, apart from a few tickets remaining for the last of THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S WALKING TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS on Sunday October 3rd at noon. Email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com to book.

Map of the Gentle Author’s Tour drawn by Adam Dant

Join me on a ramble through Spitalfields taking less than two hours, but walking through two thousand years of history. Encounter just a few of the people who have made the place distinctive and visit Quaker St where many of the Spitalfields Nippers lived.

Click here for further information

This boy is wearing Horace Warner’s hat

I often think of the lives of the Spitalfields Nippers. Around 1900, Photographer, Wallpaper Designer and Sunday School Teacher Horace Warner took portraits of children in Quaker St, who were some of the poorest in London at that time. When his personal album of these astonishing photographs came to light six years ago, we researched the lives of his subjects and published a book of all his portraits accompanied by biographies of the children.

Although we were shocked to discover that as many as a third did not reach adulthood, we were also surprised and heartened by the wide range of outcomes among the others. In spite of the deprivation they endured in their early years, many of these children survived to have long and fulfilled lives.

Walter Seabrook was born on 23rd May 1890 to William and Elizabeth Seabrook of Custance St, Hoxton. In 1901, when Walter’s portrait was taken by Horace Warner, the family were living at 24 & 1/2 Great Pearl St, Spitalfields, and Walter’s father worked as a printer’s labourer. At twenty-four years old, Walter was conscripted and fought in World War One but survived to marry Alice Noon on Christmas Day 1918 at St Matthew’s, Bethnal Green. By occupation, Walter was an electrician and lived at 2 Princes Court, Gibraltar Walk. He and Alice had three children – Walter born in 1919, Alice born in 1922 and Gladys born in 1924. Walter senior died in Ware, Hertfordshire, in 1971, aged eighty-one.

Sisters Wakefield

Jessica & Rosalie Wakefield. Jessica was born in Camden on January 16th 1891 and Rosalie at 47 Hamilton Buildings, Great Eastern St, Shoreditch on July 4th 1895. They were the second and last of four children born to William, a printer’s assistant, and Alice, a housewife. It seems likely they were living in Great Eastern St at the time Horace Warner photographed them, when Jessica was ten or eleven and Rosalie was five or six.

Jessica married Stanley Taylor in 1915 and they lived in Wandsworth, where she died in 1985, aged ninety-four. On July 31st 1918 at the age of twenty-three, Rosalie married Ewart Osborne, a typewriter dealer, who was also twenty-three years old, at St Mary, Balham. After five years of marriage, they had a son named Robert, in 1923, but Ewart left her and she was reported as being deaf. Eventually the couple divorced in 1927 and both married again. Rosalie died aged eighty-four in 1979, six years before her elder sister Jessica, in Waltham Forest.

Jerry Donovan, or ‘Dick Whittington & His Cat’

Jeremiah Donovan was born in 1895 in the City of London. His parents Daniel, news vendor, and Katherine Donovan originated in Ireland. They came to England and settled in Spitalfields at 14 Little Pearl St, Spitalfields. By 1901, the family were resident at Elizabeth Buildings, Boleyn Rd. Jeremiah volunteered for World War I in 1914 when he was nineteen and was stationed at first at City of London Barracks in Moorgate. He joined the Royal Artillery, looked after the horses for the gun carriages, but was gassed in France. In 1919, Jeremiah married Susan Nichols and they had one son, Bertram John Donovan, born in 1920. He died in Dalston in 1956 and is remembered by nine great grandchildren.

Adelaide Springett in all her best clothes

Adelaide Springett was born in February 1893 in the parish of St George-in-the-East, Wapping. Her father, William Springett came from Marylebone and her mother Margaret from St Lukes, Old St. Both parents were costermongers, although William was a dock labourer when he first married. Adelaide’s twin sisters, Ellen and Margaret, died at birth and another sister, Susannah, died aged four. Adelaide attended St Mary’s School and then St Joseph’s School. The addresses on her school admissions were 12 Miller’s Court, Dorset St, and then 26 Dorset St. In 1901, at eight years old, she was recorded as lodging with her mother at the Salvation Army Shelter in Hanbury St.

Adelaide Springett died in 1986 in Fulham aged ninety-three, without any traceable relatives, and the London Borough of Kensington & Chelsea Social Services Department was her executor.

Charlie Potter was born in Haggerston to John – a leather cutter in the boot trade – and Esther Potter. He was baptised on 13th June 1890 at St Peter’s, Hoxton Sq. In 1911, they were living at 13 Socrates Place, New Inn Yard, Shoreditch and he was working as a mould maker. Charlie married Martha Elms at St John’s, Hoxton, on 3rd August 1913. They had two children, Martha, born in 1914 and, Charles, born in 1916. In World War One, Charlie served in the Royal Field Artillery Regiment, number 132308. He died on 19th October 1954 at the Royal Free Hospital. By then, he and Martha were living 46 De Beauvoir Rd, Haggerston, and he left four hundred and seventy pounds to his widow.

Celia Compton was born in 11 Johnson St, Mile End, on April 28th 1886, to Charles – a wood chopper – and Mary Compton. Celia was one of nine children but only six survived into adulthood. Two elder brothers Charles, born in 1883, and William, born in 1884, both died without reaching their first birthdays, leaving Celia as the eldest. On January 25th 1904, she married George Hayday, a chairmaker who was ten years older than her. They lived at 5 George St, Hoxton, and had no children. After he died in 1933, she married Henry Wood the next year and they lived in George Sq until it was demolished in 1949. In later years, Celia became a moneylender and she died in Poplar in 1966 aged eighty years old.

Lizzie Flynn & Dolly Green

Lizzie Flynn was living at 19 Branch Place, Haggerston, when she was nine years old in 1901. Daughter of John and Isabella Flynn, she had two brothers and a sister. By 1911, the children were living with their widowed father at 89 Wilmer Gardens, Shoreditch. Their place of birth was listed as “Oxton” in the census. On 9th May 1915, Lizzie married Robert May at St. Andrew, Hoxton. He died at the age of just thirty-four in 1926 and they had no children. Lizzie died in Stepney in 1969, aged seventy-seven.

Dolly Green (Lydia Green) was living at 31 Hyde Rd, Hoxton, with her parents Edward and Selina in 1901 when she was twelve years old. Dolly had a brother and sister who had been born before her parents’ marriage in 1881. Dolly married Edward Moseley in 1909 at St Jude in Mildmay Grove and they had two children – Arthur born in 1912, who died in 1915, and Lydia born in 1914, who lived less than a year. In 1959, Edward Mosley remarried after his wife’s death.

Annie & Nellie Lyons – is it their mother at the window?

Annie & Nellie Lyons, born 1895 and 1901 respectively, were the sixth and ninth of ten children of Annie Daniels. Only half of Annie’s children survived to adulthood. Their mother’s words are recorded in the Bethnal Green Poor Law document of 1901.

“My name is Annie Daniels, I am thirty-five years old. My occupation is a street seller. I was born in Thrawl St to Samuel Daniels and Bridget Corfield. Around fifteen or sixteen years ago, I met William Lyons who is thirty-eight years old, at this time he was living at 4 Winfield St. He is a street hawker. The last known address for William is Margaret’s Place. I have had eight children: Margaret born 1888 in Beauvoir Sq. William born 1889 in Tyssen Place. Joseph born 1891 in Whiston St. William born in Tyssen Place died. James died in Haggerston Infirmary. Annie born in 1895 at Hoxton Infirmary. Lily born April, one year and four months ago at Baker’s Row. Ellen born April, one month ago at Baker’s Row. About ten or eleven years ago, I had a son called John. He was sent away around seven years ago to the Hackney Union House. My eldest daughter Margaret is living with my sister Sarah and her husband Cornelius Haggerty. My son Joseph is living with my other sister Caroline and her husband Charles Johnson. I have moved from various addresses over the last ten years and have been lodging with my sister Mary for three years in Dorset St previous to Lily’s birth.”

You may also like to read about

Upon the Subject of the Spitalfields Nippers

An Astonishing Photographic Discovery

Piotr Frac, Stained Glass Artist

We are delighted that Bethnal Green stained glass artist Piotr Frac is featured in the newly opened exhibition LONDON MAKING NOW at the Museum of London

Happy in the crypt beneath John Soane’s St John on Bethnal Green of 1828, Piotr Frac works peacefully making beautiful stained glass while the world passes by at this busiest of East End crossroads. Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I visited Piotr in his subterranean workshop and were delighted to observe his dexterity in action and admire some of his recent creations.

Piotr’s appealingly modest demeanour and soft spoken manner belie the moral courage and determination it has cost him to succeed in this rare occupation. This is to say nothing of his extraordinary skill in the cutting of glass and the melding of lead to fashion such accomplished work, or his creative talent in contriving designs that draw upon the age-old traditions of stained glass but are unmistakably of our own time.

Gripped by a passion for the magic of stained glass at an early age, Piotr always knew this what what he had to do. Yet even to begin to make his way in his chosen profession, Piotr had to leave his home country and find a whole new life, speaking another language in another country.

It is our gain that Piotr brought his talent and capacity for work to London. That he found his spiritual home in the East End is no accident, since he follows in the footsteps of centuries of skilled migrants, starting with the Huguenots in the sixteenth century, who have immeasurably enriched our culture with their creative energies.

“I am from a working class family in Byton, Silesia, in the south of Poland. My interest in stained glass began when I was ten or eleven years old and I went with my school to see Krakow Cathedral. The stained glass was something beautiful and that was the first time in my life I saw it. I was inspired by the colours and the light, it still excites me.

I always had an interest in drawing and painting – so, after high school, I went to a school of sculpture where they taught stained glass restoration. This was more than twenty years ago, but it was the start of my journey with stained glass. After I got my diploma in the restoration of stained glass, I worked on a project at a church for a few weeks before university. I studied art education in Silesia and I learnt painting, sculpture and calligraphy. I believe every artist needs a background in drawing and painting.

My ambition was to do stained glass, but there were hardly any jobs of any kind – I sold fish in the market in winter and I worked in a hospital, I took whatever I could get. Around 2005, I decided to leave the country. I had some Polish friends who had come to London and they helped me find a place to stay in Brixton. In the beginning, it was very difficult for me because of the language barrier. Without English, it was hard for me to communicate and find a job here. I worked on building sites. Every morning I got up at five and I walked around with this piece of paper which told me how to ask for a job. Someone wrote down a phonetic version of the words for me and I asked at building sites. After two weeks, I got a labouring job.

I lived in many places south of the river but seven years ago I moved to East London and I have stayed here ever since. At first I lived in the Hackney Rd near Victoria Park and I am still in that area, close the Roman Rd. I visited stained glass workshops but I could not get a job because I could not communicate. I did not want to work as a labourer forever so I decided to go to language school to learn English and this helped me a lot. At the English school here in the crypt of St John’s Bethnal Green, my teacher asked us to prepare a talk about myself and my interests. So I talked about my profession as a stained glass artist and my teacher introduced me to a stone carver in the crypt workshop. He told me, ‘If you are willing to teach stained glass classes, you are welcome to use the workshop.’ I started eight years ago with one student.

My first commission was to repair a Victorian glass door. Most of my work has been Victorian and Edwardian windows and doors, which has allowed me to survive because there are plenty that need repair or replacement. There are not a lot of creative commissions on offer but sometimes people want something different.

Two years ago, I won a competition to design a window for St John’s Hackney. It took a year for them to approve the design and I am in the middle of working on it now. I need to finish and install it. Also the Museum of London bought a piece of mine. It is gorilla from a triptych of gorillas and it will be displayed there next year.

Once I moved to East London, I felt I belonged to here – not only because I started my workshop but because I met my wife, Akiko, here. In 2016, I become a British citizen so now I am a permanent member of the community.

Stained glass is a wonderful medium to work with and always looks fantastic because it changes all the time with the light, in different times of the day and seasons of the year. I believe there is a great potential for stained glass in modern architecture.

These days I am able to make a living and I would like to become more recognised as a stained glass artist. I am seeking more ambitious commissions.”

Constructing a nineteenth century door panel

A panel from Piotr’s triptych of gorillas

Piotr’s first panel designed and made in London

Piotr with one of his stained glass classes in the crypt of St John’s Bethnal Green

Repairing a Victorian glass door

Restoring nineteenth century church glass

Before repair

After repair

Piotr Frac, Stained Glass Artist

Studio portraits © Sarah Ainslie

Contact Piotr Frac direct to commission stained glass

You may also like to read about

Remembering Jessica Strang

Contributing Writer Rosie Dastgir recalls her friend and neighbour in Whitechapel, the remarkable Jessica Strang, photographer & activist (1938–2021)

Portrait by Mervyn Peake, 1959/60

I first met Jessica Strang, a South African photographer and campaigner, in the late nineties when she became my neighbour round the corner in Whitechapel. The old East End weaver’s house with its light-filled loft, formerly used by workers at their looms, was ideal for Jessica. It was a space filled with a lifetime’s repository of photos, art works, furniture, found objects, postcards and bric-a-brac. She was a magpie for visually interesting and arresting things.

Here was a Basquiat-style painting by one of the neighbours. There was a portrait of an Afghan by Irma Stern, the celebrated South African artist, that had been purchased by her father at a charity auction to raise money for the defence at the 1956 Treason Trial of Nelson Mandela and others in Johannesburg. These works sat happily amongst her dizzying array of things: the little wire bicycle sculptures from South Africa, the beaded red ribbon for AIDS remembrance brooches, the hand-carved wooden gorilla, the clock designed by her son, the plethora of postcards, bottle tops, bags and textiles. Every piece carried a story which she recounted to me.

Jessica was born and grew up in a middle class family in Johannesburg, the daughter of German refugees. She came to London in the late fifties to study Graphic Design at the Central School of Art & Design but attended Mervyn Peake’s Fine Art classes instead. After college, she was one of those who set up the design group that became Pentagram where she worked with architect, Theo Crosby.

She started taking photographs in earnest, creating a library of Crosby’s architectural works, and developing her own work into an astonishingly expansive collection of photography. She was never without a camera in hand, documenting people, places and things wherever she went. Nothing and nobody escaped her eye, it was a compulsion that reflected her zest for capturing life before it outran her. She relished everything and wanted to save it all. She was eager to photograph the home delivery of my first child in a pool, but in the end – luckily for me – she settled for an atmospheric shot outside our house. It was hard to say no to Jessica.

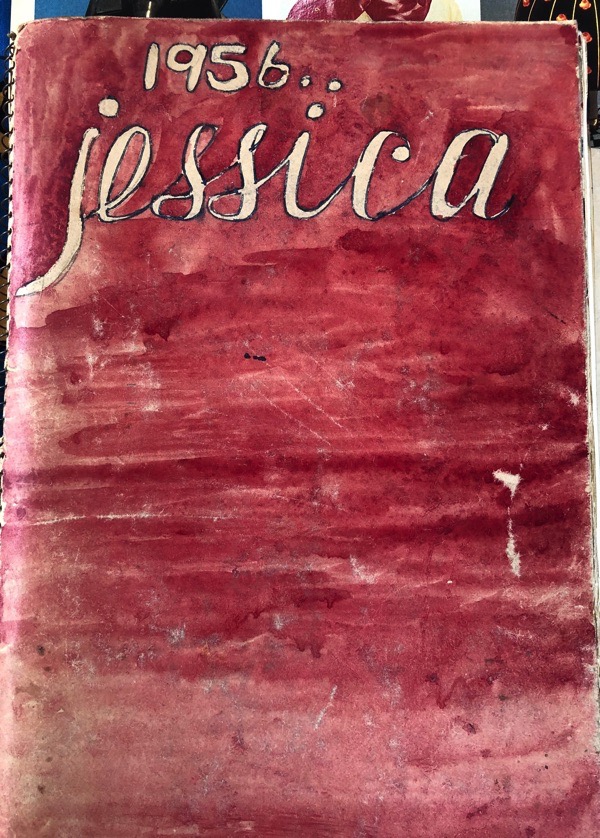

Her hunger for the world existed from early girlhood. That same keen purpose is evident in the scrapbook journals she kept as a teenager, bright collages of glued-in tickets, memos, theatre programmes, souvenirs from her trip to Europe on the BOAC Comet, all carefully collated alongside her pithy entries about her job at Stuttafords, the Johannesburg department store known as the Harrods of South Africa, where she worked to save for her travels abroad.

From the sixties, Jessica was active in the Anti-Apartheid movement, joining regular protests outside the South African embassy in Trafalgar Sq. She and her father, Edward Joseph, raised funds for the London staging in 1961 of the black South African jazz hit musical King Kong starring Miriam Makeba, about the life and times of boxer, Ezekiel Dlamini, set against the backdrop of the township, Sofiatown. Throughout the nineties, Jessica raised scholarships for black South African artists to come to London. This was a harsh time for these artists and she supported and befriended them while in a strange land, arranging space to create their art while sharing the sights and sounds of her adopted city, as well as her own kitchen for suppers and chat.

Jessica first visited Europe in 1952 on the fabled and short lived Comet BOAC aircraft, whose many delights she recorded in one of her journals. She brought fresh fruit from South Africa for her aunt in London, only to be apprehended at customs. In those days, when oranges were prized and seasonal, the prospect of giving them up made her cry so persuasively that the duty officer caved in and waved her through. She never shied away from wrangling her way past an official.

In the early seventies, she bought a small parcel of land on Hereford Rd in Notting Hill and commissioned her old boss from Pentagram to design her a house. In the aftermath of a broken first marriage, she stipulated that it should be a place where nobody could stay for more than two nights. Theo Crosby rose to the challenge. With its tiny spare room and open plan, high ceilings and exposed brick, her little home was ideal for her and her burgeoning work. When Tim Oliver moved in later, she insisted he must share the place with her two cats and, soon afterwards, Cleo was born. By the time their second child Orlando arrived, the space was squeezed so they upped sticks for a bigger house in Ladbroke Grove.

During this phase, she developed her photography by travelling round the world accompanying Tim to medical conferences, and in 1984, her first book came out, Working Women: A Photographic Collection of Women with a Purpose. She also worked as Dick Bruna’s Miffy licensing agent, ensuring that the Dutch rabbit was rendered correctly and not commercially exploited.

It was after her elderly mother’s death and the children had left home, that Jessica and Tim decided to move to the East End, so that Tim, an oncology consultant and professor, could walk to work at the nearby Royal London Hospital after decades of commuting on the Underground. Jessica had been reluctant to move to the area until that point, perhaps because of its associations with her grandfather who had fled from pogroms to London in 1904, only to be orphaned when his parents died in a refugee camp in Goodman’s Fields. He had been sent to live in Leeds with a kindly family who encouraged him to explore his Jewish background and he had emigrated to Bulawayo where he found a small community around the synagogue.

Ever since she left Hereford Rd, Jessica’s wish had been to find another site to design and build a house for her photography collection and her accumulation of artefacts. She searched and searched but it seemed impossible. So she and Tim settled in the Whitechapel weaver’s house on Halcrow St until she discovered Brody House, an Art Deco sequin factory in Aldgate near Petticoat Lane. Her flat there was a sun lit eyrie on the fifth floor, with panoramic views across the East End and a terrace for her olive trees, geraniums, and ferns.

There were frequent visitors, old and new friends, colleagues and neighbours who gathered regularly for suppers and drinks. These were boozy and convivial evenings when her raucous laughter floated out into the night. Jessica was forceful, loving and determined: nobody could resist the broad wingspan of her friendship.

In the first years of this century, Jessica suffered a burst pituitary tumour but recovered remarkably. Thanks to Tim, she kept travelling, walking everywhere and photographing the unfurling world. She visited us in New York City in 2011, after our family left Whitechapel, and she was immediately at home in the hectic streets of Brooklyn. An inveterate traveller and adventurer, she winkled out curiosities in the Atlantic Avenue shops and photographing every sight and incident that caught her eye.

By now, her library of images had increased to over 400,000 images. Tim found a PhD student to help her document and catalogue her photos. Still, her work did not abate, as if some hidden part of her knew what to do and kept going, even after a stroke caused loss of speech and dementia crept up on her in her final years.

Jessica died at home in June with her family around her, surrounded by her life’s work in its dazzling variety. She is survived by her husband Tim, a professor emeritus at Queen Mary University, her daughter, Cleo, a doctor in South London, and her son, Orlando, an architect based in Singapore.

Jessica Strang & Tim Oliver in the seventies

Jessica’s photos of her tiny house in Notting Hill designed by Theo Crosby

Jessica & Tim with their children, Cleo & Orlando

Jessica in Petticoat Lane in recent years

Jessica’s view from the top of a sequin factory in Aldgate

You can see Jessica Strang’s photography on Instagram @ jessicastrang_photolibrary

You may like to read these other stories by Rosie Dastgir

Rosie Dastgir’s Letter From Tokyo

At Tjaden’s Electrical Repair Shop

Gulam Taslim, Funeral Director

Lost Spitalfields

Looking towards Spitalfields from Aldgate East

London can be a grief-inducing city. Everyone loves the London they first knew, whether as the place they grew up or the city they arrived in. As the years pass, this city bound with your formative experience changes, bearing less and less resemblance to the place you discovered. Your London is taken from you. Your sense of loss grows until eventually your memory of the London you remember becomes more vivid than the London you see before you and you become a stranger in the place that you know best. This is what London can do to you.

In Spitalfields, the experience has been especially poignant in recent years with the redevelopment of the Fruit & Vegetable Market, the Fruit & Wool Exchange and Norton Folgate. Yet these photographs reveal another Spitalfields that only a few remember, this is lost Spitalfields.

Spital Sq was an eighteenth century square linking Bishopsgate with the market that was destroyed within living memory, existing now only as a phantom presence in these murky old photographs and in the fond remembrance of senior East Enders. On the eastern side of Spitalfields, the nineteenth century terraces of Mile End New Town were erased in ‘slum clearances’ and replaced with blocks of social housing while, to the north, the vast Bishopsgate Goodsyard was burned to the ground in a fire that lasted for days in 1964.

Yet contemplating the history of loss in Spitalfields sets even these events within a sobering perspective. Only a feint pencil sketch of the tower records the Priory of St Mary which stood upon the site of Spital Sq until Henry VIII ‘dissolved’ it and turned the land into his artillery ground. Constructing the Eastern Counties Railway in the eighteen-thirties destroyed hundreds of homes and those residents who were displaced moved into Shoreditch, creating the overcrowded neighbourhood which became known as the Old Nichol. And it was a process that was repeated when the line was extended down to Liverpool St. Meanwhile, Commercial St was cut through Spitalfields from Aldgate to Shoreditch to transport traffic more swiftly from the docks, wreaking destruction through densely inhabited streets in the mid-nineteenth century.

So look back at these elegiac photos of what was lost in Spitalfields before your time, reconcile yourself to the loss of the past and brace yourself for the future that is arriving.

Spital Sq, only St Botolph’s Hall on the right survives today

Spital Sq photographed in 1909

Church Passage, Spital Sq, 1733, photographed in 1909 – only the market buildings survive.

17 Spital Sq, 1725

25 Spital Sq, 1733

23 Spital Sq, 1733

20 Spital Sq, 1723

20 Spital Sq, 1723

20 Spital Sq, 1732

32 Spital Sq, 1739

32 Spital Sq, 1739

5 Whites Row, 1714

6/7 Spring Walk, 1819

Buxton St, 1850

Buxton St, 1850

Former King Edward Institution, 1864, Deal St

36 Crispin St, 1713

7 Wilkes St, 1722

10 & 11 Norton Folgate, 1810 – photographed in 1909

Norton Folgate Court House, Folgate St, photographed in 1909

52 & 9a Artillery Passage, 1680s

Bishopsgate Goods Station, 1881

Shepherd’s Place arch, 1820, leading to Tenter St – photographed 1909

You may also like to read about

C. A. Mathew, Photographer

Since my walking tour of Spitalfields is fully booked, I am doing two extra walks on Saturday 2nd & Sunday 3rd October at noon. Email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com to book. Click here for full details

On the tour we visit some locations of C. A. Mathew’s photographs

Map of the Gentle Author’s Tour drawn by Adam Dant

In Crispin St, looking towards the Spitalfields Market

On Saturday April 20th 1912, C.A.Mathew walked out of Liverpool St Station with a camera in hand. No-one knows for certain why he chose to wander through the streets of Spitalfields taking photographs that day. It may be that the pictures were a commission, though this seems unlikely as they were never published. I prefer the other theory, that he was waiting for the train home to Brightlingsea in Essex where he had a studio in Tower St, and simply walked out of the station, taking these pictures to pass the time. It is not impossible that these exceptional photographs owe their existence to something as mundane as a delayed train.

Little is known of C.A.Mathew, who only started photography in 1911, the year before these pictures and died eleven years later in 1923 – yet today his beautiful set of photographs preserved at the Bishopsgate Institute exists as the most vivid evocation we have of Spitalfields at this time.

Because C.A.Mathew is such an enigmatic figure, I have conjured my own picture of him in a shabby suit and bowler hat, with a threadbare tweed coat and muffler against the chill April wind. I can see him trudging the streets of Spitalfields lugging his camera, grimacing behind his thick moustache as he squints at the sky to apprise the light and the buildings. Let me admit, it is hard to resist a sense of connection to him because of the generous humanity of some of these images. While his contemporaries sought more self-consciously picturesque staged photographs, C.A.Mathew’s pictures possess a relaxed spontaneity, even an informal quality, that allows his subjects to meet our gaze as equals. As viewer, we are put in the same position as the photographer and the residents of Spitalfields 1912 are peering at us with unknowing curiosity, while we observe them from the reverse of time’s two-way mirror.

How populated these pictures are. The streets of Spitalfields were fuller in those days – doubly surprising when you remember that this was a Jewish neighbourhood then and these photographs were taken upon the Sabbath. It is a joy to see so many children playing in the street, a sight no longer to be seen in Spitalfields. The other aspect of these photographs which is surprising to a modern eye is that the people, and especially the children, are well-dressed on the whole. They do not look like poor people and, contrary to the widespread perception that this was an area dominated by poverty at that time, I only spotted one bare-footed urchin among the hundreds of figures in these photographs.

The other source of fascination here is to see how some streets have changed beyond recognition while others remain almost identical. Most of all it is the human details that touch me, scrutinising each of the individual figures presenting themselves with dignity in their worn clothes, and the children who treat the streets as their own. Spot the boy in the photograph above standing on the truck with his hoop and the girl sitting in the pram that she is too big for. In the view through Spitalfields to Christ Church from Bishopsgate, observe the boy in the cap leaning against the lamppost in the middle of Bishopsgate with such proprietorial ease, unthinkable in today’s traffic.

These pictures are all that exists of the life of C.A.Mathew, but I think they are a fine legacy for us to remember him because they contain a whole world in these few streets, that we could never know in such vibrant detail if it were not for him. Such is the haphazard nature of human life that these images may be the consequence of a delayed train, yet irrespective of the obscure circumstances of their origin, this is photography of the highest order. C.A.Mathew was recording life.

Looking down Brushfield St towards Christ Church, Spitalfields.

Bell Lane looking towards Crispin St.

Looking up Middlesex St from Bishopsgate.

Looking down Sandys Row from Artillery Lane – observe the horse and cart approaching in the distance.

Looking down Frying Pan Alley towards Crispin St.

Looking down Middlesex St towards Bishopsgate.

Widegate St looking towards Artillery Passage.

In Spital Square, looking towards the market.

At the corner of Sandys Row and Frying Pan Alley.

At the junction of Seward St and Artillery Lane.

Looking down Artillery Lane towards Artillery Passage.

An enlargement of the picture above reveals the newshoarding announcing the sinking of the Titanic, confirming the date of this photograph as 1912.

Spitalfields as C.A.Mathew found it, Bacon’s “Citizen” Map of the City of London 1912.

Photographs courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

London, The Ever-Changing City

Distinguished Historian Gillian Tindall offers an ambivalent history of the development of London over the last five hundred years. Gillian’s books include The House by the Thames and A Tunnel Through Time, A New Route for an Old London Journey.

‘London Going Out of Town’ or ‘The March of Bricks & Mortar’ by George Cruikshank, 1829

“I remember when it was all fields round here.” How many of us have heard these words spoken by an older person describing some outer district of London? The huge spread of our metropolis is often seen as a modern evil but the truth is that each successive generation has lamented it for hundreds of years. EM Forster in his pre-First World War novel Howards End, writing of the ‘red rust’ of bricks advancing across meadows far from the main streets of the capital, was just another voice in a long, long tradition.

The red rust has been held at bay since the Town & Country Planning Act of 1934 and then by the establishment of the Green Belt. Yet the new Planning Act proposed by our present government looks set to unleash another wave of bricks. There is nothing new in attempts to curb the growth of our capital but less comforting is the fact that, although these attempts have often succeeded in moderating and organising London’s growth, they have hardly ever stopped it.

The first who tried to was Elizabeth I, by issuing a proclamation in 1580 forbidding any new house to be built within three miles of the gates of London. It did not work. Thirteen years later, the same order was reissued with objections to ‘converting great houses into several tenements… and the erecting of new buildings between London and Westminster.’ Suburban sprawl had begun.

The reference to the gates of London is significant. Like all European cities, London was a close-knit hub of small streets lined with houses, many with walled gardens behind. All was contained within the City wall and accessible only through eight fortified gates that were shut at night. But by Elizabeth’s time, England had not been invaded by for five hundred years and even the Peasants’ Revolt – when the City of London was stormed by the poor and angry – had taken place two hundred years earlier. The walls and gates were more symbolic than useful.

Before Elizabeth came to the throne, in Henry VIII’s reign, a suburb had developed beyond the Lud Gate and the Fleet River, on the slopes of what were to become Fleet St and High Holborn. To the north, Clerkenwell was still open country with just a couple of monastic houses set in fields and the other end of the City, beyond the Tower and Aldgate, was the same. But fifty years later, Elizabeth’s contemporary, John Stow, mourned encroachment upon the pastures by the Tower, where he had played as a child and fetched milk from cow-keepers.

“…this common field, all which ought to be open and free for all men… being sometime the beauty of this city on that part, is so encroached upon by the building of filthy cottages… and with other enclosures and laystalls… that in some places it scarce remaineth a sufficient highway…”

To the east, Whitechapel was already developing the utilitarian character it would maintain for several centuries while grander citizens sought to build their homes to the west. Another favoured but more distant suburb, a true out-of-town destination, was Hackney, the green and flowery village where the wealthy built themselves fine houses.

Forty years later, Civil War fortifications were constructed beyond the walls. These ditches and ramparts would have proved ineffectual defence though, as it turned out, they were never tested. Once the Commonwealth was over and Charles II was restored in triumph to the throne, the gates were opened wide, and left that way.

Quite soon, blocks of stones were being hacked out of the walls to construct houses. In 1666, when the Fire destroyed much of the City, many of those who lost their homes moved further out to Spitalfields, Shoreditch and Bethnal Green to the east, or westward to Holborn and St Giles, to Soho and St James’s. The City was becoming part of a far bigger conurbation than that which today is known as Central London.

For the next two centuries, there was a natural limitation to growth. As long all vehicles were horse-drawn, the metropolis was as dependent on fodder as the modern city is upon fuel for lorries and cars. Hay was as essential as petrol today. While London was still a small walled city, it was not hard to provide it. Those green meadows Stow wrote about had been just over the door-step, or rather the gate-step, and in distant rural districts such as St Pancras or Stepney there was so much space for grass that a range of other arable crops such as wheat and barley were also grown. But by the end of Elizabeth’s reign the demand for hay had increased to the level that all the fields as far as Highgate were given over to its production.

Two hundred years later, when London had grown a great deal more, swallowing Islington and Knightsbridge, and creating Camden Town, all the land as far as Watford was said to be ‘down to hay.’ Yet there is a limit to how far a horse-drawn cart can travel in a day to bring fodder back to the metropolis. In early nineteenth century London, developers filled in all the space between the villages and old urban suburbs, such as Shoreditch, were crammed with ever more people.

The true explosion in London’s size could not happen until horsepower was superseded. When railways began arriving in the eighteen-forties, deliveries of hay or anything else from much further afield became possible. In 1863, the Metropolitan Underground Railway opened as the first in the world, offering the possibility of ‘living in the country and working in town.’ For centuries, most employees had walked back and forth between work and home each day. Many of them adopted the new way of life encouraged by cheap workmen’s fares. Within a generation, the country where the new houses were being built turned into suburbia – ‘Metroland’ – and then inexorably into an outlying part of the ever-expanding capital. EM Forster’s ‘red rust’ became manifest.

Yet the fodder-for-horses problem remained until vehicles could be powered by another fuel and until electricity replaced steam power to run the Underground, permitting deeper tunnels and more destinations. Both these transformative developments happened within a few years of each other.

Much of our present Underground was built between 1900 and 1910. Meanwhile street traffic, which was almost entirely horse-drawn at the turn of the century, became dominated by horseless-carriages within a decade. The last horse bus in London ran on the eve of the First World War and the last horse-tram eight months later. During the War, those who still had traditional status as ‘carriage people’ sold off their horses and bought motorcars. Livery stables shut all over the capital as garages opened.

By the end of the century, most Londoners were dependent on their motor cars and ancient road-systems were crudely transformed to accommodate this twentieth century monster. Yet now the assumptions that made King Car dominant for the last hundred years are unravelling. The question of how London must adapt once again is huge. The only certainty is change.

John Stow, the first historian of London, grieved over the redevelopment of the city in his lifetime

Photograph © Estate of Colin O’Brien

You may like to read these other stories by Gillian Tindall

Memories of Ship Tavern Passage

At Captain Cook’s House in Mile End