The Executions Of Old London

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

Coinciding with the new exhibition EXECUTIONS at Museum of London Docklands, I present this fine election of execution broadsides. In the days before internet, television or cinema, public executions were a popular source of entertainment. I am grateful to Ed Maggs, fourth generation proprietor of Maggs Bros booksellers, who drew my attention to these gruesome wonders.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution Broadside of Henry Horler for the murder of his wife Ann Horler on 17th November 1852, at Sun St, Bishopsgate.

Ann Horler’s mother, Ann Rogers, came to take her daughter away from her husband Henry Horler on the night before the murder was discovered. She had been told that her daughter had been abused by her husband. Henry Horler insisted his wife would not go with her mother that night, but Mrs Rogers should return in the morning for her. The next morning Ann Horler was found dead.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of John Wiggins at Newgate, 15th October 1867, for the murder of Agnes Oakes on the morning of Wednesday 24th July at Limehouse. Printed with the trial and execution of Louis Bordier, a Frenchman charged with the murder of Mary Ann Snow on the 3rd September 1867 on Old Kent Rd.

Agnes Oakes lived with John Wiggins as his wife for about six months prior to the murder. Neighbours said they witnessed John beating Agnes and she had said she would leave him if he did not stop.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of Michael Barrett, the Fenian, and last man to be hanged in public, on the 26th May 1868, Newgate. Barrett was arrested for the “Clerkenwell Explosion” on 13th December 1867 which killed twelve people and injured many others. Barrett was the only Irish Republican to be convicted of the crime, five others were acquitted.

This tragic event occurred during an attempt to release Richard O’Sullivan Burke from prison. The explosion was misjudged and not only did it blast a sixty foot hole in the prison wall, (O’Sullivan Burke is thought to have been killed in the blast), a number of tenements on Corporation Lane were also destroyed.

The conviction appeared largely to be based on the fact Michael Barrett was a Fenian and that several witnesses claimed he may have been in London at the time. Barrett stated he was in Glasgow on the day of the explosion and if ‘there were 10,000 armed Fenians in London, it was ridiculous to suppose they would send to Glasgow for a person of no higher abilities than himself.’

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of John Devine for the murder of Joseph Duck in the early morning of 11th March 1863, Little Chesterfield St, Marylebone.

The condemned pleaded not guilty to the crime which appeared to result from a robbery that went wrong. The jury was sympathetic to Devine and, although the verdict returned was guilty, there was a strong recommendation to mercy, as they were of the ‘opinion that the prisoner inflicted the injuries on the deceased while in the act of robbing him; but, at the same time they thought he did not intend to murder him.’ The scene of the execution was described thus: ’There was not a large concourse assembled to witness the sad spectacle, nor was there exhibited by those present any of that unseemly demonstrativeness which they are wont to indulge in.’

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of the nurse Catherine Wilson for the murder by poisoning with colchicine of her patient Maria Soames in Albert St, Bloomsbury, on the 18th October 1856. The last woman to be publicly hanged in London.

This was Catherine Wilson’s second indictment for poisoning a patient, having been acquitted the first time round to the astonishment of many. When the first trial took place, on 16th June 1862, in the documents the accused appeared as Constance Wilson and was also occasionally found under the alias Catherine Taylor/Turner. Immediately, she was taken back in to custody and charged with the murder of Maria Soames. During the initial trial, the police had been busy putting together evidence of further victims and even exhumed several bodies, including that of Ann Atkinson, Peter Mawer and James Dixon, who was one of Ms. Wilson’s former lovers. In seven of these exhumed bodies a variety of poisons were found.

The Judge presiding said he had ’never heard of a case in which it was more clearly proved that murder had been committed, and where the excruciating pain and agony of the victim were watched with so much deliberation by the murderer.”

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of Dr William Palmer, for the poisoning of John Parsons Cook at Stafford. Dr Palmer was described by Charles Dickens as ‘The greatest villain that ever stood at the Old Bailey’ in his article on ’The Demeanor of Murderers’. He is also referenced in several novels and an Alfred Hitchcock film.

He was also suspected, although never indicted, of the murder of his four children, all of whom died in infancy, his wife Ann Palmer, Brother Walter Palmer, a house guest Leonard Bladen, and his mother-in-law, Ann Mary Thornton. The doctor benefited financially from all of these deaths.

Dr Palmer was executed at Stafford Prison Saturday 14th June 1856. Although not mentioned in this broadside, the prisoner was said to have had an interesting exchange with the prison governor moments before his death. When Dr Palmer was asked to confess his crimes, the exchange went thus:

Dr Palmer – ’Cook did not die from strychnine.’

Prison Governor -’There is not time for quibbling – Did you or did you not kill Cook?’

Dr Palmer – ’The Lord Chief Justice summed up for poisoning by strychnine.’

In the trial text, it is stated Dr Palmer reiterated he was: ‘innocent of poisoning Cook by strychnia.’

The Judge stated in his summation: ‘Whether it is the first and only offence of this sort which you have committed is certainly known only to God and your own conscience.’

Dr Palmer became notorious for his supposed crimes. It was said 20,000 people attended his execution and a wax figure of him was displayed at Madame Tussauds in the Chamber of Horrors from 1857 – 1979.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Trial broadside of Thomas Cooper,‘would-be’ highwayman, for the murder of Timothy Daly, policeman, and also for shooting at and maiming, with intent to murder, Charles Mott (a baker), and Charles Moss (another police officer) on 5th May at Highbury.

The defence, Mr Hory, addressed the jury, saying ‘for the first time during the seven years that he had been at the bar, he was called upon to address a jury upon a charge, conviction upon which was certain death. He almost felt that his anxiety would defeat itself. He could not help referring to different published statements, most of them monstrous perversions of established fact, and all calculated to excite the prejudices of a jury. When he saw these he could hardly fancy they lived in an enlightened age’.

Mr Hory made the case that the prisoner was not of sound mind, citing attempts of suicide, and claims of being Dick Turpin and Richard III. But this defence was unsuccessful with the jury reached a verdict of guilty, and Thomas Cooper was sentenced to death and executed July 7th 1842.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of Charles Peace the notorious Blackheath burglar, for the murder of Arthur Dyson at Banner Cross, on the 29th November 1876.

Charles Peace murdered Arthur Dyson after become obsessed with Mr Dyson’s wife. Then Peace went on the run for two years with a £100 reward on his head, until he was betrayed by his mistress, Mrs Sue Thompson, who revealed his whereabouts to the police. She never received her expected reward as the police claimed her information did not lead directly to Peace’s arrest. He was caught on 10th October 1878, by Constable Robinson, who Peace shot at five times.

Subsequently, a waxwork figure of Charles Peace featured at Madame Tussaud’s, and two films and several books were produced about his life and crimes.

Images courtesy of Maggs Bros

You may also like to read about

Dorothy Rendell’s East End Portraits

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

Dorothy Rendell trained at St Martin’s School of Art during the Second World War and was encouraged by Henry Lamb, Carel Weight and Orovinda Pissarro at the beginning of her career. While teaching art at Harry Gosling School in Whitechapel for forty years, she undertook portraits of her favourite pupils and, subsequently, drew people in the doctor’s waiting room at the Jubilee St Practice. These dignified and tender images comprise an important social record of East Enders in the post-war years.

“When I started teaching I thought I would teach in the West End but they would not take women, so I had to move to the East End – but I don’t regret that at all because I got so wrapped up in it and there were all these places where I could go and draw,” Dorothy admitted to me.

“This little boy was one of the pupils I taught. A little horror! He’d been badly behaved – so the head teacher told me, ‘Take him and make him sit for you!’ So he had to sit still for about two or three days. I think I did a painting of him too”

“This is a nice little girl who had a terrible life. She was pretty and I liked her, so I drew her. I think I probably went to her house. It was squared up for a painting but I don’t know what happened to the painting. Children are very good to draw as long as they are not commissioned, when they are commissioned they are hellish. One mother came to me and wanted a portrait of her daughter. She looked a nice kid and I didn’t charge very much. She wore jeans, but when she turned up she was all dressed up – it was awful!”

“I used to give them their drawings. They used to beg me for them and were so persuasive that I used to hand them over, until one day a boy took my drawing and folded it up in half and put it in his pocket. I nearly screamed! They never did that in Italy, they treasure their drawings there.”

“This is Harry. Miss Parry, the head teacher, she adored this drawing. Harry was really thick and he used to look at you with that blank expression, but he was marvellously funny and he made a tremendous effort. Somebody who used to work with me said, ‘I’m going to bring Harry to Miss Parry’s funeral,’ and I said, ‘But he’ll be middle aged now.’ She found him and he came to the funeral. I couldn’t believe it. He was a lorry driver for Charringtons.”

“This was a little Afghan girl, I thought she was beautiful. She was a vain little girl who would sit for hours in the art room. Miss Parry thought it was better for pupils to sit with me than to sit and do nothing, so she would send the badly behaved ones to the art room and I would draw them. They liked being drawn, they were flattered by it.”

“I never had any absentees from my art classes, they were always very keen. As my head teacher used to say, ‘They’ll always go to art with you!’ They enjoyed doing it. There were always a certain number who could not draw, who found it very difficult. I would get them started making patterns but they would think they could not do that. So I would say, ‘Yes you can.’ I would get something like an electric light bulb and say, ‘Make some patterns from what you can see with that.’ – repeating and so forth. And they would come up with some marvellous things. Then they got keen. You have to think up strange things to get children really interested.”

“This little girl, I got to know her mother and father, and she went on to grammar school. The children of immigrants always did much better than the English ones because their parents wanted them to work.”

“This was in the doctor’s waiting room. Quite a well known doctor round here invited me to draw there.”

Pictures courtesy of Dorothy Rendell Collection at Bishopsgate Insititute

You may also like to read about

John James Baddeley, Engraver, Die Sinker & Lord Mayor

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

“I haven’t time in my life for much else than work”

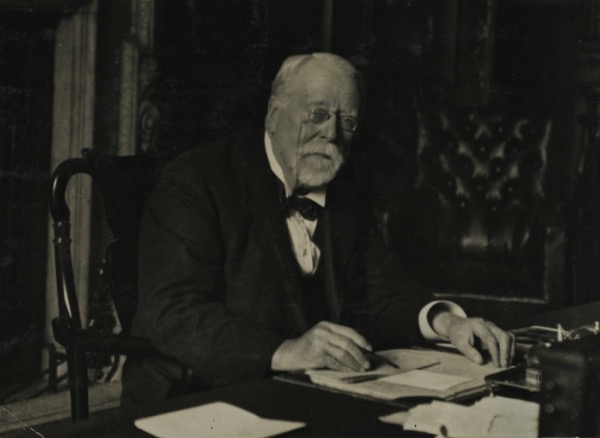

One hundred years ago this week, John James Baddeley, an engraver and die sinker, became Lord Mayor of London. Today his company, Baddeley Brothers, still flourishes as the pre-eminent specialist printers and envelope makers.

These photographs show Sir John James Baddeley, Baronet – known colloquially as ‘JJ’ – taking a Sunday morning walk with his wife through the empty City of London in 1922, when he was Lord Mayor and residing at the Mansion House.

With his top hat, cane and Edwardian beard, the eighty-year-old gentleman looks the epitome of self-confident respectability and worldly success, yet there is a poignancy in his excursion through the deserted streets, when the hubbub of the week was stilled, pausing to gaze into the windows of the shabby little printshops that competed to supply letterheads and engraved stationery to the banks, stock-brokers and insurance companies of the City.

In those days, all transactions and share issues required elaborately-engraved forms and there was a legal obligation to list all the directors on business notepaper which needed constant reprinting and adjustment of the dies whenever there were staff changes. Consequently, the City of London teemed with small highly-specialised companies eager to fulfil the constant demand for all this printed paper.

At the time of these photographs, nearly sixty years had passed since, at the age of twenty-three in October 1865, JJ had set up independently as a die sinker in a shared workshop in Little Bell Alley at the back of the Bank of England under entirely inauspicious circumstances. The eldest of thirteen children, JJ had already acquired plenty of experience of the long hours of labour required to scrape a modest living in the trade of die-sinking and engraving when he was apprenticed to his father at fourteen years old in Hackney.

Even by the standards of nineteenth century fiction, it was an extraordinary story of personal advancement. JJ oversaw the transformation of his business from an artisan trade to an industrialised process employing hundreds in a single factory. Born into an ever-increasing family that struggled to keep themselves, he inherited a powerful work ethos and a burning desire to overcome the injustice his father had suffered. JJ can only have been a driven man, the eldest brother who set his own modest industry in motion and then drew in his younger siblings to assist with spectacular results.

“In January 1857, I started my business life with my father in his workshop in Hackney at the back of the house at the Triangle in Mare St where I first donned a white apron, turned up my shirt sleeves and did all sorts of jobs,” he wrote of his apprenticeship in the trade of die sinking, “sweeping up and lighting the forge fire, warming the dies and later forging them on the anvil, then annealing them and afterwards filing them to shape and, when engraved, hardening them and tempering them.”

“During the whole time there, I was the errand boy, taking the dies and stamps to the few customers that my father had, Jarrett at No 3 Poulty being the chief one,” he recalled at the end of his life, “Many a time have I trudged – in winter with my feet crippled with chilblains – to the Poultry and at night to his other shop in Regent St. During the time I was at work with my father I had very good health, but we were all poorly-clad and none of the children had overcoats.”

In 1851, Griffith Jarrett exhibited his popular embossing press at the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, ordering the dies from JJ’s father who took on a larger house for his growing family and more apprentices on the basis of this seemingly-endless new source of income. Yet Griffith Jarrett exploited the situation mercilessly, inducing JJ’s father to make dies for him alone, then driving the prices down and eventually turning JJ’s father into a mere journeyman who worked like a slave and found he had little left after he had paid his production costs, impoverishing the family.

When, as a boy, JJ walked through the snow at night to deliver the dies for his father to Griffith Jarrett’s Regent St shop at 8pm or 10pm, Jarrett sometimes gave JJ tuppence to ride part of the way home. It was an offence of meagre omission that JJ never forgot. “These two pennies were the beginnings of my savings which enabled me to set up in business for myself and to defy the man who for more than twenty years had my father in his clutches,” admitted JJ in later years.

“I began work by doing simple dies for my father at journeyman prices and began making traces, stops, commas, letter punches and other small tools. By the end of the year, I managed to get a few orders for dies from Messrs John Simmons & Sons who had a warehouse in Norton Folgate,” he recorded, looking back on his small beginnings in the light of his big success, “I turned out my work quicker than my competitors and gave better personal attention to my customers, trusting to this rather than obtaining orders by quoting lower prices.”

“These were very strenuous and hard working times, I commenced work at nine and seldom leaving before ten o’clock at night,” he confessed – but twenty years later, in 1885, the company occupied a six storey factory at the corner of Moor Lane and employed more than three hundred people. It was an astonishing outcome.

Yet, while embracing the potential of technological progress so effectively, JJ possessed an equal passion for craft and tradition – especially the history of Cripplegate where he became a Warden. “In 1889, an attempt to take down the St Giles Church Tower, after a good fight I saved it,” he wrote with succint satisfaction. Later, devoting a year of his life to writing an authoritative history of Cripplegate, he prefaced it with the words – “Let us never live where there is nothing ancient, nothing to connect us with our forefathers.”

No wonder then that, as an old man, John James Baddeley chose to stroll through the empty streets of London on Sunday mornings, pausing to look into old print shop windows, and consider his own place in the long history of printing and the City.

John James Baddeley’s business card

Over 300 hands were employed at Baddeley Brothers in Moor Lane, 1888

Engineering & Press Making Dept in the basement

Paper & Envelope Department on the first floor where over fifty hands are employed in envelope making, gumming, black and silver bordering, scoring etc

Die Sinking & Engraving Dept – The largest in the trade, twenty-one die sinkers are employed alongside twenty-one copperplate engravers and eight wood engravers.

Litho Dept on the second floor with fourteen copperplate presses, three litho machines, nine litho presses and three Waddie lithos

The view from the Mansion House in 1922

JJ in the Venetian Parlour at the Mansion House

You may also like to read about

Samuel & Elizabeth Pepys At St Olave’s

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

Do you see Elizabeth Pepys, leaning out from her monument and directing her gaze across the church to where Samuel sat in the gallery opposite? These days the gallery has long gone but, since her late husband became celebrated for his journal, a memorial to him was installed in 1883 where the gallery once was, which contains a portrait bust that peers back eternally at Elizabeth. Consequently, they will always see eye-to-eye, even if they are forever separated by the nave.

St Olave’s on the corner of Seething Lane has long been one of my favourite City churches. Dating from the eleventh century, it is a rare survivor of the Great Fire and the London Blitz. When you walk in from Hart St, three steps down into the nave immediately reveal you are entering an ancient building, where gothic vaults and medieval monuments conjure an atmosphere more reminiscent of a country church than one in the City of London.

Samuel Pepys moved into this parish when he was appointed Commissioner of the Navy Board and came to live next to the Navy Office at the rear of the church, noting his arrival at “my house in Seething Lane” in his journal on July 18th 1660. It was here that Pepys recorded the volatile events of the subsequent decade, the Plague and the Fire.

In Seething Lane, a gateway adorned with skulls as memento mori survives from that time. Pepys saw the gate from his house across the road and could walk out of the Navy Office and through it into the churchyard, where an external staircase led him straight into the private Navy Office pew in the gallery.

The churchyard itself is swollen above surrounding ground level by the vast number of bodies interred within and, even today, the gardeners constantly unearth human bones. When Elizabeth and the staff of the Navy Office took refuge from the Plague at Woolwich, Pepys stayed behind in the City. Countless times, he walked back and forth between his house and the Navy Office and St Olave’s as the body count escalated through the summer of 1665. “The sickness in general thickens round us, and particularly upon our neighbourhood,” he wrote to Sir William Coventry in grim resignation.

The following year, Pepys employed workers from the dockyard to pull down empty houses surrounding the Navy Office and his own home to create fire breaks. “About 2 in the morning my wife calls me up and tells me of new cries of fire, it being come to … the bottom of our lane,” he recorded on 6th September 1666.

In the seventeenth century vestry room where a plaster angel presides solemnly from the ceiling, I was able to open Samuel Pepys’ prayer book. It was heart-stopping to turn the pages. Dark leather covers embossed with intricate designs enfold the volume, which he embellished with religious engravings and an elaborate hand-drawn calligraphic title page.

Samuel and Elizabeth Pepys are buried in a vault beneath the nave. Within living memory, when the Victorian font was removed, a hole was exposed that led to a chamber with a passage that led to a hidden chapel where a tunnel was dug to reach the Pepys vault. Scholars would love to know if he was buried with his bladder stone upon its silver mount, but no investigation has yet been permitted.

If you seek Samuel Pepys, St Olave’s is undoubtedly where you can find him. Walk in beneath the gate laden with skulls, across the graveyard bulging with the bodies of the long dead, cast your eyes along the flower beds for any shards of human bone, and enter the church where Samuel and Elizabeth regard each other from either side of the nave eternally.

St Olave’s at the corner of Seething Lane

“To our own church, and at noon, by invitation, Sir W Pen dined with me and Mrs Hester, my Lady Betten’s kinswoman, to dinner from church with me, and we were very merry. So to church again, and heard a simple fellow upon the praise of Church musique, and exclaiming against men’s wearing their hats on in the church, but I slept part of the sermon, till latter prayer and blessing and all was done without waking which I never did in my life…” SAMUEL PEPYS, Sunday 17th November, 1661

Samuel Pepys’ memorial in the south aisle

Samuel Pepys’ prayerbook

Engraved nativity and fine calligraphy upon the title page of Pepys’ prayerbook

Door to the vestry

The oldest monument in the church, 1566

Memorial of Peter Capponi, a Florentine merchant & spy, 1582

Paul Bayning, 1616, was an Alderman of the City & member of the Levant company

A Norwegian flag hangs in honour of St Olave

The gate where Pepys walked in from the Navy Office across the street

Sculpture of Samuel Pepys in the churchyard

You may also like to read about

Clive Murphy, Phillumenist

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

Clive Murphy, Phillumenist

Nothing about this youthful photo of the late novelist, oral historian and writer of ribald rhymes, Clive Murphy – resplendent here in a well-pressed tweed suit and with his hair neatly brushed – would suggest that he was a Phillumenist. Even people who have knew him since he came to live in Spitalfields in 1973 never had an inkling. In fact, evidence of his Phillumeny only came to light when Clive donated his literary archive to the Bishopsgate Institute and a non-descript blue album was uncovered among his papers, dating from the era of this picture and with the price ten shillings and sixpence still written in pencil in the front.

I was astonished when I saw the beautiful album and I asked Clive to tell me the story behind it. “I was a Phillumenist,” he admitted to me in a whisper, “But I broke all the rules in taking the labels off the matchboxes and cutting the backs off matchbooks. A true Phillumenist would have a thousand fits to see my collection.” It was the first time Clive had examined his album of matchbox labels and matchbook covers since 1951 when, at the age of thirteen, he forsook Phillumeny – a diversion that had occupied him through boarding school in Dublin from 1944 onwards.

“A memory is coming back to me of a wooden box that I made in carpentry class which I used to keep them in, until I put them in this album,” said Clive, getting lost in thought, “I wonder where it is?” We surveyed page after page of brightly-coloured labels from all over the world pasted in neat rows and organised by their country of origin, inscribed by Clive with blue ink in a careful italic hand at the top of each leaf. “I have no memory of doing this.” he confided to me as he scanned his handiwork in wonder,“Why is the memory so selective?”

“I was ill-advised and I do feel sorry in retrospect that they are not as a professional collector would wish,” he concluded with a sigh, “But I do like them for all kinds of other reasons, I admire my method and my eye for a pattern, and I like the fact that I occupied myself – I’m glad I had a hobby.”

We enjoyed a quiet half hour, turning the pages and admiring the designs, chuckling over anachronisms and reflecting on how national identities have changed since these labels were produced. Mostly, we delighted at the intricacy of thought and ingenuity of the decoration once applied to something as inconsequential as matches.

“There was this boy called Spring-Rice whose mother lived in New York and every week she sent him a letter with a matchbox label in the envelope for me.” Clive recalled with pleasure, “We had breaks twice each morning at school, when the letters were given out, and how I used to long for him to get a letter, to see if there was another label for my collection.” The extraordinary global range of the labels in Clive’s album reflects the widely scattered locations of the parents of the pupils at his boarding school in Dublin, and the collection was a cunning ploy that permitted the schoolboy Clive to feel at the centre of the world.

“You don’t realise you’re doing something interesting, you’re just doing it because you like pasting labels in an album and having them sent to you from all over the world.” said Clive with characteristic self-deprecation, yet it was apparent to me that Phillumeny prefigured his wider appreciation of what is otherwise ill-considered in existence. It is a sensibility that found full expression in Clive’s work as an oral historian, recording the lives of ordinary people with scrupulous attention to detail, and editing and publishing them with such panache.

Clive Murphy, Phillumenist

Images courtesy of the Clive Murphy Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to read my other stories about Clive Murphy

The Forgotten Corners Of Old London

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

Who knows what you might find lurking in the forgotten corners of old London? Like this lonely old waxwork of Charles II who once adorned a side aisle of Westminster Abbey, peering out through a haze of graffiti engraved upon his pane by mischievous tourists with diamond rings.

As one with a pathological devotion to walking through London’s side-streets and byways, seeking to avoid the main roads wherever possible, these glass slides of the forgotten corners of London – used long ago by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society for magic lantern shows at the Bishopsgate Institute – hold a special appeal for me. I have elaborate routes across the city which permit me to walk from one side to the other exclusively by way of the back streets and I discover all manner of delights neglected by those who solely inhabit the broad thoroughfares.

And so it is with many of these extraordinary pictures that show us the things which usually nobody bothers to photograph. There are a lot of glass slides of the exterior of Buckingham Palace in the collection but, personally, I am much more interested in the roof space above Richard III’s palace of Crosby Hall that once stood in Bishopsgate, and in the unlikely paraphernalia which accumulated in the crypt of the Carmelite Monastery or the Cow Shed at the Tower of London, a hundred years ago. These pictures satisfy my perverse curiosity to visit the spaces closed off to visitors at historic buildings, in preference to seeing the public rooms.

Within these forgotten corners, there are always further mysteries to be explored. I wonder who pitched a teepee in the undergrowth next to the moat at Fulham Palace in 1920. I wonder if that is a cannon or a chimney pot abandoned in the crypt at the Carmelite monastery. I wonder why that man had a bucket, a piece of string and a plank inside the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral. I wonder what those fat books were next to the stove in the Worshipful Company of Apothecaries’ shop. I wonder who was pulling that girl out of the photograph in Woolwich Gardens. I wonder who put that dish in the roof of Crosby Hall. I wonder why Charles II had no legs. The pictures set me wondering.

It is what we cannot know that endows these photographs with such poignancy. Like errant pieces from lost jigsaws, they inspire us to imagine the full picture that we shall never be party to.

Tiltyard Gate, Eltham Palace, c. 1930

Refuse collecting at London Zoo, c. 1910

Passage in Highgate, c. 1910

Westminster Dust Carts, c. 1910

The Jewel Tower, Westminster, 1921

Fifteenth century brickwork at Charterhouse Wash House, c1910

Middle Temple Lane, c. 1910

Carmelite monastery crypt, c. 1910

The Moat at Fulham Palace, c. 1920

Clifford’s Inn, c. 1910

Top of inner dome at St Paul’s Cathedral, c. 1920

Apothecaries’ Hall Quadrangle, c. 1920

Worshipful Company of Apothecaries’ Shop, c.1920

Unidentified destroyed building near St Paul’s, c. 1940

Merchant Taylors’ Hall, c. 1920

Crouch End Old Baptist Chapel, c. 1900

Woolwich Gardens, c. 1910

The roof of Crosby Hall, Richard III’s palace in Bishopsgate , c. 1910

Refreshment stall in St James’ Park, c. 1910

River Wandle at Wandsworth, c. 1920

Corridor at Battersea Rise House, c. 1900

Tram emerging from the Kingsway Tunnel, c. 1920

Between the interior and exterior domes at St Paul’s Cathedral, c. 1920

Fossilised tree trunk on Tooting Common, c. 1920

St Dunstan-in-the-East, 1911

Cow shed at the Queen’s House, Tower of London, c. 1910

Boundary marks for St Benet Gracechurch, St Andrew Hubbard and St Dionis Backchurch in Talbot Court, c. 1910

Lincoln’s Inn gateway seen from Old Hall, c. 1910

St Bride’s Fleet St, c. 1920

Glass slides courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

The Tragical Death Of An Apple Pie

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

The time in the year for apple pie has arrived. So I take this opportunity to present The Tragical Death of an Apple Pie, an alphabet rhyme first published in 1671, in a version produced by Jemmy Catnach in the eighteen-twenties.

Poet, compositor and publisher, Catnach moved to London from Newcastle in 1812 and set up Seven Dials Press in Monmouth Court, producing more than four thousand chapbooks and broadsides in the next quarter century. Anointed as the high priest of street literature and eager to feed a seemingly-endless appetite for cheap printed novelties in the capital, Catnach put forth a multifarious list of titles, from lurid crime and political satire to juvenile rhymes and comic ballads, priced famously at a quarterpenny or a ‘farden.’

A An Apple Pie

B Bit it

C Cut it

D Dealt it

E Did eat it

F Fought for it

G Got it

H Had it

J Join’d for it

K Kept it

L Long’d for it

M Mourned for it

N Nodded at it

O Open’d it

P Peeped into it

Q Quartered it

R Ran for it

S Stole it

T Took it

V View’d it

W Wanted it

XYZ and & all wished for a piece in hand

Dame Dumpling who made the Apple Pie

You may also like to take a look at