George Dickinson, Sales Manager

George Dickinson, Sales Manager at Jackie Brafman’s in Petticoat Lane

Through the nineteenth and twentieth century, Petticoat Lane market was one of the wonders of London, until deregulation in the eighties permitted shops across the capital to open and the market lost its monopoly on Sunday trading.

One of the most celebrated and popular traders was Jackie Brafman, still remembered for his distinctive auctioneering style, standing on a table in the Lane and selling dresses at rock bottom prices.

George Dickinson worked as Sales Manager for Jackie Brafman for thirty-three years during the heyday of the sixties, seventies and eighties. Losing his father when he was still a child and coming to London from Newcastle as a teenager, George discovered a new family in Petticoat Lane and a surrogate father in Jackie Brafman.

“I was born as George Albert Dickinson in Heaton, Newcastle Upon Tyne, one of six brothers and a sister. We had a very good family life and we were happy until my father died when I was nine. In those days, they did not know whether it was cancer or tuberculosis. He was manager of a brewery and a very good piano player. He used to get behind the piano in the dining room and play the chords.

My mother had to sell our four-bedroomed house and we moved in with an aunt. After three months, the aunt died and we had to get out again. We moved to a small terraced house in Scotswood, and my mother did cleaning and worked in a pub in the centre of Newcastle. Our neighbour was a retired miner and every month he got a ton of coal from the coal board. His wife used to come ask, ‘George, Would you like to shovel it into the coal hole? If anybody wants to buy some coal, it’s sixpence a bucket.’ I used to do that for her and she gave me a shilling.

I lived there until I was fourteen when I was allowed to leave school and go to work because of the situation. My eldest brother became a fireman in Newcastle during the war and another was sent to Burma as a medic. There’s only me and my younger brother left now.

I had two jobs in Newcastle. First in a bedding company, making divans, and then I had a go at French polishing, but I got the sack from that – why I do not know. So I went to try to get a job at a fifty shilling tailors and I think I lasted about two days, I did not like it at all.

At fifteen years old, I decided to come to London. My sister met me at King’s Cross and took me to Camden Town. I was just mesmerised by it all. It was Irish and Greeks. A nice place to live at the time. She had a dairy in Pratt St and I lived with her for a little while. I got a job at a textile firm in the West End as a storeman and travelled back and forth by bus.

Then I got my call-up papers at the age of eighteen in 1956. I did ten weeks training at Winchester Barracks and from there we flew from Luton airport to Singapore where we were given a week’s jungle training before being sent to a rubber plantation which was a base for an army camp.

When I came out of the forces, I returned to the old firm but they went into liquidation, so I went to another firm which I did not like at all. I was walking around the West End and I bumped into a driver from a dress company, Peter. I had known him from the old firm. I said, ‘I’m looking for a job, Peter.’ He asked, ‘Do you mind what you do?’ I replied, ‘No, not at all.’ So he told me, ‘There’s a job going. It’s a Mr Brafman, he owns a place in Petticoat Lane.’ I did not know what Petticoat Lane was. Evidently it was a market but, coming from Newcastle, I did not have a clue.

So I phoned him up, went down the same day for the interview and met him in the dress shop. He asked me, ‘What are you doing now?’ I explained who I had worked for and he must have phoned them up, because he told me, ‘Mr Flansburgh thought a lot of you.’ After that, he said, ‘When can you start?’ ‘Any time,’ I replied. ‘Start on Monday,’ he told me.

Jackie Brafman was a terrific boss. At first, I did general things, sweeping and clearing up hangers. There were two shops, a small one which was retail and the large one was wholesale, full of stock. Over the course of time, I started selling in the wholesale department. Eventually, I met Mrs Brafman who was a pet lover. They bought two dogs and called them George & Albert after me. I built up a reputation as a good salesman and I never had to ask for a rise all the years I was there. If the boss was going to a boxing match, he always took me, even if it was Mohammed Ali. I was ringside with him when Cooper fought Ali and he split his glove. A very good man. He was like another father to me. He insisted I call him ‘Jack’ from the second week at work, so eventually I called him ‘JB.’ He did not mind that at all.

On Sunday, he used to stand on a table and auction goods to the public in Petticoat Lane. I arranged for a special desk to be made that was big enough and strong enough to stand on. We had iron rails suspended above from the ceiling where we could hang dresses, a few of each in different sizes. I used to stand on a ladder and feed the clothes to him. I even picked up a bit of Yiddish, I could count the dress sizes in Yiddish. He would tell the customers he had sizes from ten to eighteen and they put their hands up, asking ‘Have you got a ten? Have you got a twelve?’ and I would be feeding the dress out to the crowd. On two occasions, he was in hospital so I got up and auctioneered. It was at Christmas time and we did very well. He was so well known and liked.

One of his favourite sayings was ‘You’ve heard of Christian Dior, I’m the Yiddisher Dior!’ He always had a bottle of whisky on the shelf and he would say, ‘George, get the paper cups.’ Maggie, a regular customer, would come in and he would ask, ‘Would you like a drink, Maggie?’ He poured whisky into these paper cups and topped it up with cola. He would tell her, ‘I’m only doing this to get you a little but tipsy so you don’t know what you are buying.’

There was another guy who used to come in and stand on the side of the shop, and I realised what he wanted. I asked, ‘Can I help you, Sir?’ and he said, ‘No, I’m waiting for one of the ladies to serve me.’ So I called, ‘Celia, Can you come and look after this gentleman?’ Eventually, I gained his trust and he showed me his photographs of him in dresses with wigs and makeup. He looked brilliant. He was a drag artist, but he did not want the lads to know. He used to spend a lot of money and only Celia could serve him.

I became manager of the wholesale department, a double-fronted shop in Wentworth St, opposite the public toilets. People came from all over the world. Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana, Saudi Arabia and Arabia, as well as from all over this country. There were five girls working in the retail shop and we used to employ schoolkids to stand outside by the stall and make sure nothing got pinched.

Jack would go to the West End and buy stuff from Clifton, which was very big fashion house for larger size women, and Peter Kay and Remark and Kidmark. These were all top names years ago. He would buy ‘over-makes’ from them. If they were given an order from Marks & Spencer for a thousand garments, they might make twelve hundred in case of any problems. Jack would buy the extra at a knock-down price. We might sell a dress for four-fifty retail and three-fifty wholesale, but Jack got them for seventy pence each. He done so well Jackie.

Jackie’s father Maurice Brafman lived in Nightingale House, a home for the elderly.It was a beautiful place and he had his own room. The dining room was just like a hotel. He used to phone me up on a Friday morning and say, ‘George, Can you get me some groceries?’ I would go to Kossoff’s and buy cholla for him, and collect his kosher meat from the butcher. He did like his salami and occasionally a bit of fruit. I would put it all in a bag and, when I was going home, I would make a stop in Nightingale Lane to deliver his groceries. He would always check them and pick an argument about something. He would say, ‘You haven’t brought me so and so!’ and I would reply, ‘Mr Brafman, it’s in the bottom of the bag.’ ‘Alright,’ he would concede but he would always find fault. It was lovely seeing him. He lasted about five years there.

In the end, Jack took very ill. He was only coming in occasionally. He had a silver cloud Rolls Royce and I drove it a couple of times up to the West End to pick up stuff when he was not too well. He ran the business from home and his wife would come in occasionally to collect the takings. Sometimes, he would turn up in his wife’s car and stagger in to say, ‘Hello.’

He had two sons and two daughters and eventually Mark, the eldest brother, opened clothes shops all over London called ‘Mark One.’ His wife caught him with another woman and took him for everything. He was worth a fortune and he had a house with a ballroom in the middle. The youngest son, David, went into the business in Petticoat Lane and closed the shop.

Working at Jackie Brafman’s was the best part of my life, apart from getting married and having daughters. When I first came to London to find work at fifteen years old, I was rather shy and a bit inward. By working with Jack and talking to him, I changed. When he was not too busy, Jack would call me into the retail shop and ask me questions, ‘What do you think of this?’ I would give him my opinion and gradually I built up a bit of confidence. Mrs Brafman told me one day, ‘You know, Mr Brafman says you are the backbone of the business.’ I felt so good about it.”

Jackie Brafman, Petticoat Lane (Photograph courtesy of Jewish East End Celebration Society)

George Dickinson, Sales Manager at Jackie Brafman’s

Read these other stories about Petticoat Lane

Laurie Allen of Petticoat Lane

The Wax Sellers of Wentworth St

Tony Bock At Watney Market

Tony Bock took these pictures of Watney Market while working as a photographer on the East London Advertiser between 1973 and 1978. Within living memory, there had been a thriving street market in Watney St, yet by the late seventies it was blighted by redevelopment and Tony recorded the last stalwarts trading amidst the ruins.

In the nineteenth century, Watney Market had been one of London’s largest markets, rivalling Petticoat Lane. By the turn of the century, there were two hundred stalls and one hundred shops, including an early branch of J.Sainsbury. As a new initiative to revive Watney Market is launched this spring, Tony’s poignant photographs offer a timely reminder of the life of the market before the concrete precinct.

Born in Paddington yet brought up in Canada, Tony Bock came back to London after being thrown out of photography school and lived in the East End where his mother’s family originated, before returning to embark on a thirty-year career as a photojournalist at The Toronto Star. Recalling his sojourn in the East End and contemplating his candid portraits of the traders, Tony described the Watney Market he knew.

“I photographed the shopkeepers and market traders in Watney St in the final year, before the last of it was torn down. Joe the Grocer is shown sitting in his shop, which can be seen in a later photograph, being demolished.

In the late seventies, when Lyn – my wife to be – and I, were living in Wapping, Watney Market was our closest street market, just one stop away on the old East London Line. It was already clear that ‘the end was nigh,’ but there were still some stallholders hanging on. My memory is that there were maybe dozen old-timers, but I don’t think I ever counted.

The north end of Watney St had been demolished in the late sixties when a large redevelopment was promised. Yet, not only did it take longer to build than the Olympic Park in Stratford, but a massive tin fence had been erected around the site which cut off access to Commercial Rd. So foot and road traffic was down, as only those living nearby came to the market any more. The neighbourhood had always been closely tied to the river until 1969 when the shutting of the London Docks signalled the change that was coming.

The remaining buildings in Watney St were badly neglected and it was clear they had no future. Most of the flats above the shops were abandoned and there were derelict lots in the terrace which had been there since the blitz. The market stalls were mostly on the north side of what was then a half-abandoned railway viaduct. This was the old London & Blackwall Railway that would be reborn ten years later as the Docklands Light Railway and prompt the redevelopment we see today.

So the traders were trapped. The new shopping precinct had been under construction for years. But where could they go in the meantime? The new precinct would take several more years before it was ready and business on what was left of the street was fading.

Walking through Watney St last year, apart from a few stalls in the precinct, I could see little evidence there was once a great market there. In the seventies, there were a couple of pubs, The Old House At Home and The Lord Nelson, in the midst of the market. Today there are still a few old shops left on the Cable St end of Watney St, but the only remnant I could spot of the market I knew was the sign from The Old House At Home rendered onto the wall of an Asian grocer.

I remember one day Lyn came home, upset about a cat living on the market that had its whiskers cut off. I went straight back to Watney St and found the beautiful tortoiseshell cat hiding under a parked car. When I called her, she came to me without any hesitation and made herself right at home in our flat. Of course, she was pregnant, giving us five lovely kittens and we kept one of them, taking him to Toronto with us.”

Eileen Armstrong, trader in fruit and vegetables

Joe the Grocer

Gladys McGee, poet and member of the Basement Writers’ group, who wrote eloquently of her life in Wapping and Shadwell. Gladys was living around the corner from the market in Cable St at this time.

Joe the Grocer under demolition.

Frames from a contact sheet showing the new shopping precinct.

Photographs copyright © Tony Bock

You may like to see these other photographs by Tony Bock

The Auriculas Of Spitalfields

An Auricula Theatre

In horticultural lore, auriculas have always been associated with Spitalfields and writer Patricia Cleveland-Peck has a mission to bring them back again. She believes that the Huguenots brought them here more than three centuries ago, perhaps snatching a twist of seeds as they fled their homeland and then cultivating them in the enclosed gardens of the merchants’ grand houses, and in the weavers’ yards and allotments, thus initiating a passionate culture of domestic horticulture among the working people of the East End which endures to this day.

You only have to cast your eyes upon the wonder of an auricula theatre filled with specimens in bloom – as I did in Patricia’s Sussex garden – to understand why these most artificial of flowers can hold you in thrall with the infinite variety of their colour and form. “They are much more like pets than plants,” Patricia admitted to me as we stood in her greenhouse surrounded by seedlings,“because you have to look after them daily, feed them twice a week in the growing season, remove offshoots and repot them once a year. Yet they’re not hard to grow and it’s very relaxing, the perfect antidote to writing, because when you are stuck for an idea you can always tend your auriculas.” Patricia taught herself old French and Latin to research the history of the auricula, but the summit of her investigation was when she reached the top of the Kitzbüheler Horn, high in the Austrian Alps where the ancestor plants of the cultivated varieties are to be found.

Auriculas were first recorded in England in the Elizabethan period as a passtime of the elite but it was in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that they became a widespread passion amongst horticulturalists of all classes. In 1795, John Thelwall, son of a Spitalfields silk mercer wrote, “I remember the time myself when a man who was a tolerable workman in the fields had generally beside the apartment in which he carried on his vocation, a small summer house and a narrow slip of a garden at the outskirts of the town where he spent his Monday either in flying his pigeons or raising his tulips.” Auriculas were included alongside tulips among those prized species known as the “Floristry Flowers,” plants renowned for their status, which were grown for competition by flower fanciers at “Florists’ Feasts,” the precursors of the modern flower show. These events were recorded as taking place in Spitalfields with prizes such as a copper kettle or a ladle and, after the day’s judging, the plants were all placed upon a long table where the contests sat to enjoy a meal together known as “a shilling ordinary.”

In the nineteenth century, Henry Mayhew wrote of the weavers of Spitalfields that “their love of flowers to this day is a strongly marked characteristic of the class.” and, in 1840, Edward Church who lived in Spital Sq recorded that “the weavers were almost the only botanists of their day in the metropolis.” It was this enthusiasm that maintained a regular flower market in Bethnal Green which evolved into the Columbia Rd Flower Market of our day.

Known variously in the past as ricklers, painted ladies and bears’ ears, auriculas come in different classes, show auriculas, alpines, doubles, stripes and borders – each class containing a vast diversity of variants. Beyond their aesthetic appeal, Patricia is interested in the political, religious, cultural and economic history of the auricula, but the best starting point to commence your relationship with this fascinating plant is to feast your eyes upon the dizzying collective spectacle of star performers gathered in an auricula theatre. As Sacheverell Sitwell once wrote, “The perfection of a stage auricula is that of the most exquisite Meissen porcelain or of the most lovely silk stuffs of Isfahan and yet it is a living growing thing.”

Mrs Cairns Old Blue – a border auricula

Glenelg – a show-fancy green-edged auricula

Piers Telford – a gold-centred alpine auricula

Taffetta – a show-self auricula

Seen a Ghost – a show-striped auricula

Sirius – gold-centred alpine auricula

Coventry St – a show-self auricula

M. L. King – show-self auricula

Mrs Herne – gold-centred alpine auricula

Dales Red – border auricula

Pink Gem – double auricula

Summer Wine – gold-centred alpine auricula

McWatt’s Blue – border auricula

Rajah – show-fancy auricula

Cornmeal – show-green-edged auricula

Fanny Meerbeek – show-fancy auricula

Piglet – double auricula

Basuto – gold-centred alpine auricula

Blue Velvet – border auricula

Patricia Cleveland-Peck in her greenhouse.

You may also like to take a look at

The Highdays & Holidays Of Old London

On Easter Monday, let us consider the highdays & holidays of old London

Boys lining up at The Oval, c.1930

School is out. Work is out. All of London is on the lam. Everyone is on the streets. Everyone is in the parks. What is going on? Is it a jamboree? Is it a wingding? Is it a shindig? Is it a bevy? Is it a bash?

These are the high days and holidays of old London, as recorded on glass slides by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society and once used for magic lantern shows at the Bishopsgate Institute.

No doubt these lectures had an educational purpose, elucidating the remote origins of London’s quaint old ceremonies. No doubt they had a patriotic purpose to encourage wonder and sentiment at the marvel of royal pageantry. Yet the simple truth is that Londoners – in common with the rest of humanity – are always eager for novelty, entertainment and spectacle, always seeking any excuse to have fun. And London is a city ripe with all kinds of opportunities for amusement, as illustrated by these magnificent photographs of its citizens at play.

Are you ready? Are you togged up? Did you brush your hair? Did you polish your shoes? There is no time to lose. We need the make the most of our high days and holidays. And we need to get there before the parade passes by.

At Hampstead Heath, c.1910.

Walls Ice Cream vendor, c.1920.

At Hampstead Heath, c.1910.

At Hampstead Heath, c.1910.

Balloon ascent at Crystal Palace, Sydenham, c.1930.

At the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens, 1896.

Christ’s Hospital Procession across bridge on St Matthews Day, 1936.

A cycle excursion to The Spotted Dog in West Ham, 1930.

Pancake Greaze at Westminster School on Shrove Tuesday, c.1910.

Variety at the Shepherds Bush Empire, c.1920.

Dignitaries visit the Chelsea Royal Hospital, c.1920.

Games at the Foundling Hospital, Bloomsbury, c.1920.

Riders in Rotten Row, Hyde Park, c.1910.

Physiotherapy at a Sanatorium, 1916.

Vintners’ Company, Master’s Installation procession, City of London, c.1920.

Boating on the lake in Battersea Park, c.1920.

The King’s Coach, c.1911.

Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession, 1897.

Lord Mayor’s Procession passing St Paul’s, 1933.

Policemen gives directions to ladies at the coronation of Edward VII, 1902.

After the procession for the coronation of George V, c.1911.

Observance of the feast of Charles I at Church of St. Andrew-by-the-Wardrobe, 1932.

Chief Yeoman Warder oversees the Beating of the Bounds at the Tower of London, 1920.

Schoolchildren Beating the Bounds at the Tower of London, 1920.

A cycle excursion to Chingford Old Church, c.1910.

Litterbugs at Hampstead Heath, c.1930.

The Foundling Hospital Anti-Litter Band, c.1930.

Distribution of sixpences to widows at St Bartholomew the Great on Good Friday, c.1920.

Visiting the Cast Court to see Trajan’s Column at the Victoria & Albert Museum, c.1920.

A trip from Chelsea Pier, c.1910.

Doggett’s Coat & Badge Race, c.1920.

Feeding pigeons outside St Paul’s, c.1910.

Building the Great Wheel, Earls Court, c.1910.

Glass slides copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

Viscountess Boudica’s Easter

On Easter Sunday, we celebrate our dearly beloved Viscountess Boudica of Bethnal Green who once entertained us with her seasonal frolics and capers but now is exiled to Uttoxeter

She may be no Spring chicken but that never stopped the indefatigable Viscountess Boudica of Bethnal Green from dressing up as an Easter chick!

As is her custom at each of the festivals which mark our passage through the year, she embraced the spirit of the occasion wholeheartedly – festooning her tiny flat with seasonal decor and contriving a special outfit for herself that suited the tenor of the day. “Easter’s about renewal – birth, life and death – the end of one thing and the beginning of another,” she assured me when I arrived, getting right to the heart of it at once with characteristic forthrightness.

I felt like a child visiting a beloved grandmother or favourite aunt whenever I call round to see Viscountess Boudica because, although I never knew what treats lie in store, I was never disappointed. Even as I walked in the door, I knew that days of preparation preceded my visit. Naturally for Easter there were a great many fluffy creatures in evidence, ducks and rabbits recalling her rural childhood. “When my uncle had his farm, I used to put the little chicks in my pocket and carry them round with me,” she confided with a nostalgic grin, as she led me over to admire the wonder of her Easter garden where yellow creatures of varying sizes were gathering upon a small mat of greengrocer’s grass, around a tree hung with glass eggs, as if in expectation of a sacred ritual.

I cast my eyes around at the plethora of Easter cards, testifying to the popularity of the Viscountess, and her Easter bunting and Easter fairy lights that adorned the walls. There could be no question that the festival was anything other than Easter in this place. “As a child, I used to get a twig and spray it with paint and hang eggs from it,” she explained, recalling the modest origin of the current extravaganza and adding, “I hope this will inspire others to decorate their homes.”

“Cadbury’s Dairy Milk is my favourite,” she confessed to me, chuckling in excited anticipation and patting her waistline warily, “I probably will eat a lot of chocolate on Easter Monday – once I start eating chocolate, I can’t stop.” And then, just like that beloved grandmother or favourite aunt, Viscountess Boudica kindly slipped a chocolate egg into my hands, as I said my farewell and carried it off under my arm back to Spitalfields as a proud trophy of the day.

Viscountess Boudica writes her Easter cards

“yellow creatures of varying sizes were gathering upon a small mat of greengrocer’s grass, around a tree hung with glass eggs, as if in expectation of a sacred ritual”

Viscountess Boudica turns Weather Girl to present the forecast for the Easter Bank Holiday – “I predict a dull start with a few patches of sunshine and some isolated showers. In the West Country, it will be nice all day with temperatures between sixty and eighty degrees Farenheit. There will be a small breeze on the coast and sea temperature of around fifty-nine degrees Farenheit.”

Easter blessings to you from Viscountess Boudica!

Viscountess Boudica and her fluffy friends

Be sure to follow Viscountess Boudica’s blog There’s More To Life Than Heaven & Earth

Take a look at

The Departure of Viscountess Boudica

Viscountess Boudica’s Domestic Appliances

Viscountess Boudica’s Halloween

Viscountess Boudica’s Christmas

Viscountess Boudica’s Valentine’s Day

Viscountess Boudica’s St Patrick’s Day

Read my original profile of Mark Petty, Trendsetter

and take a look at Mark Petty’s Multicoloured Coats

Robson Cezar’s New Whitechapel Market Houses

Through these last winter months, Spitalfields artist Robson Cezar has been collecting wooden fruit crates in Whitechapel Market on the way to his studio in Bow again, and making them into a new series of intricately crafted little wooden houses.

Each one is a day’s work for Robson and many are recognisable as inspired by buildings around the East End – including houses, signal boxes and a chapel. Photographer Sarah Ainslie visited him in his studio this week to document his creations. Every one is different and each comes with an LED light and battery.

The houses are £85 each plus £3.50 postage & packing. We are selling them on a first-come-first-served basis, so if you would like one please email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com giving your first, second and third choice, and we will supply payment details. We can only post these within the United Kingdom.

These houses are sculptures not toys and we do not recommend them for children under the age of twelve.

“During the first lockdown I walked the empty streets and reflected on the importance of having a safe and comfortable living space, especially during a time of crisis. I was inspired to create small wooden house sculptures using fruit and vegetable crates. My experience growing up in a tiny wooden house without any comfort in a favela in Brazil influences my work. To find scrap wood, I go to Whitechapel Market, which I pass every day on my way to my studio in Bow.”

Robson Cezar

C

E

F

G

H

I

K

M

N

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

Robson Cezar’s Wooden Houses from Whitechapel

The Way Of The Cross In Stepney

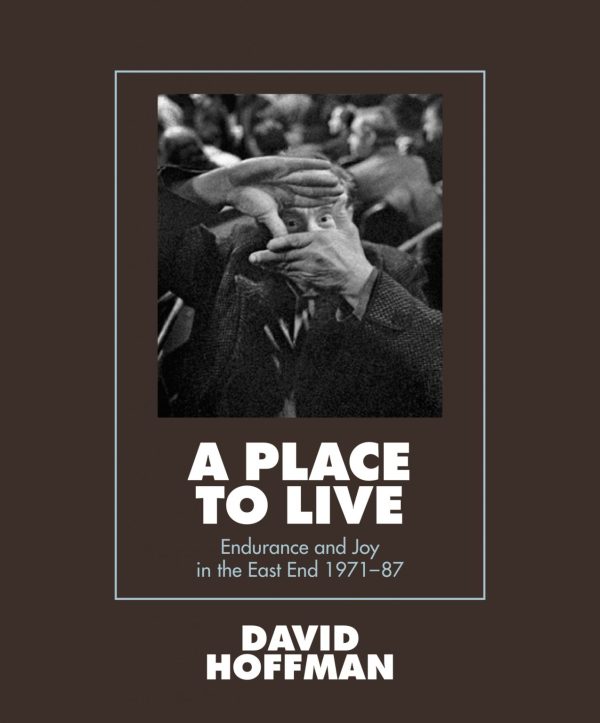

David Hoffman undertook a significant body of photography documenting the East End in the seventies and eighties that I plan to publish this year as a book entitled, A PLACE TO LIVE, Endurance & Joy in Whitechapel, accompanied by a major photographic exhibition at House of Annetta in Spitalfields.

I believe David’s work is such an important social document, distinguished by its generous humanity and aesthetic flair, that I must publish a collected volume. I have raised around a third of the money and have a growing list of supporters for this project now, so if you share my appreciation of David’s photography and would support this endeavour, please drop me a line at spitalfieldslife@gmail.com

A costume fitting

In the late seventies, Contributing Photographer David Hoffman documented the religious drama enacted upon the streets of Stepney around Easter time, recording astonishing images of magical realist intensity which feel closer to the medieval world than to our own day.

Gordon Kendall who played Jesus wrote this memory of his experience.

‘On a cold wet and depressing evening in April 1980, well over 100 actors, production crew and 2000 people lived through the experience of Our Lord’s Way Of The Cross enacted in the streets and estates of Stepney.

The excitement and challenge of playing Jesus really began on the Sunday before the event. Some of the actors were trying out their costumes and they looked very impressive.

Half way through the rehearsal, I needed to visit the toilet and so excused myself from the bodyguard of soldiers in costume. I knocked at the door of a flat. A lady came out and I requested the use of her toilet. She looked at me very oddly – she was a elderly lady – and she asked me who I was. I replied I was playing the part of Jesus and she flashed me a look which revealed she did not believe me, but she said ‘Come in.’

As I went through the flat I could see someone sleeping on the sofa in the lounge. When I closed the bathroom door, I could hear the woman waking up her friend and saying, ‘Nell, there’s a man in the toilet who says he’s Jesus.’ Then I heard some rapid movement and I could only wonder at the thoughts of this woman, struggling to her feet.

There was a knocking at the front door as I came out of the toilet and the two women opened it to be confronted by a fierce Roman Centurion in full regalia, asking if Jesus was in the flat. Fortunately, they relaxed into joyous smiles and it was kisses and handshakes all round as we departed.’

Roman soldiers

Jesus in flares

The arrest of the two thieves

Preparing for the crucifixion

A Roman legion marching

Pilate speaks

Roman soldiers at St Dunstan’s

Jesus consoles Mary

Bespectacled Jesus

Roman Centurion in regalia

Jesus gives himself up

The march to the crucifixion

The soldiers stripping Jesus of his raiments

Crucifixion courtesy of Whitbread

Behold, Jesus is risen in St Dunstan’s Church!

Photographs copyright © David Hoffman

You may also like to take a look at