Beatrice Ali, Salvation Army Hostel Dweller

“She was dancing in a tutu under my window, directing the traffic and shouting ‘Up the Common Market!” explained Clive Murphy with a wan smile, as he sat in the kitchen of his flat above the Aladin Curry House in Brick Lane last week, recalling how he met Beatrice Ali, the well known local personality and eccentric, pictured here by East End photographer Paul Trevor in the nineteen seventies.

Recording thirty hours of conversations with Beatrice telling her story, between May and October 1975, Clive edited her words to became “The Good Deeds of a Good Woman,” the first book he published in his “Ordinary Lives” oral history series in 1976. It is a fascinating account which explains the human story behind Beatrice’s famously idiosyncratic behaviour, restoring dignity to an individual who had been rendered marginal by her own misfortune and become the object of derision in her own community.

“Whenever I could find her, I asked her to come and see me to make a tape recording. We entered into a collaboration agreement, splitting the royalties fifty-fifty. She did it because she was burning with resentment at some people and she wanted to talk about how kind she was. I think she was very lonely and very glad to have someone to talk to.” Clive told me, describing the origin of the book.“She threw milk bottles at windows,” added Clive affectionately,” and when the book was published she used to shout at mine, ‘I know you’ve got a woman up there!’ She was as lively as a trivet. She was just perfect.”

“The Good Deeds of a Good Woman” is a candid account of a mixed-race marriage that ended badly when Basit, Beatrice’s husband of thirty years, left her in 1965, once their sons were grown up, selling their home in Spitalfields and returning to East Pakistan where he took a young wife. Yet in spite of the tragedy of her circumstance, Beatrice demonstrated an endearingly unsentimental wit and lack of self pity in the telling of her tale, in vigorous language that held my rapt attention, without a break, from cover to cover.

Returning one day to discover a padlock on her own front door, Beatrice slept on Liverpool St Station before moving into a Salvation Army Hostel. Censured by many English people for her inter-racial marriage, Beatrice found herself rejected by the Bangladeshi people too. Even her sons disowned her, and she sought to retain self-respect by undertaking good deeds, while struggling to support herself as best she could. In such straightened circumstances, every action of her existence became a brave gesture of defiance against the odds. Today, Beatrice’s story of her courageous daily battle for survival on the streets of Spitalfields is essential reading for anyone who wants to understand the evolving life of the East End.

“I sat nights in Liverpool St Station and after that I’d go into the toilet and have a wash and do my hair, then come back and have another sit down. Then I’d go and stand at the meths drinkers’ fire in Spitalfields Market till two men come round with soup and bread between twelve and quarter past. I’d have that and then have a walk around or stand at the coffee stall in Commercial Street, and then I’d go back to the station and buy a ticket and go and doze off in the Waiting Room. Policeman would come in and wake you up. ‘Have you got a ticket?’– and I’d show it. ‘Won’t be long. I’m going to work at five o’clock.’ ‘Oh! Sorry to worry you.'”

Once Beatrice was living in the Salvation Army Hostel, she could only return at night, filling her days with casual jobs and altruistic deeds to restore her reputation and self-esteem, as these two extracts illustrate.

“I’m a fool when I’ve got money. I’d give to anybody. About four months ago I was walking through Fieldgate St and in Fieldgate St there’s a butcher’s shop, and I saw an old man with two sticks and he’s looking at these lamb chops. ‘Oh they’re such lovely big meaty chops!’ He looked at me. ‘Oh Mum,’ he said, ‘I wouldn’t half love four chops! Two for me and two for my wife!‘ I had money. I went in. I said, ‘Four of them nice meaty chops, love!’ How much do you think they were? A pound! I said to the old man. ‘They’re only a pound, love.’ He said, ‘You’re not buying them for me, surely?!’ I said, ‘Yes’ and I bought him a tin of peas as well. Funny thing, I was lucky that day. If you help anybody, you’re often lucky. I went into the betting office and I won £10 on the horses.”

“Someone saw me with an old man, they said, ‘I wouldn’t do it. I wouldn’t have no interest if I went out with a man like that.’ I said, ‘What you would do and what I would do is two separate things. My heart is soft, if I thought anybody needed the money for food and I had it, I’d buy it for them. If I had two shillings and someone needed a shilling, I’d give it to them.’ This old man, bless him, he couldn’t thank me enough. He said, ‘You are so kind to me. I do appreciate this kindness.’ The morning after I put him in this armchair, I went round the Maltese shop near the nuns’ and got him a cup of tea and brought it to him – he’d been out all night sitting in this armchair. ‘Here you are, Dad. Here’s a cup of tea and a couple of cigarettes. And here you are, here’s ten pence.’ I said, ‘Are you all right, Dad?’ He said, ‘I’m all right. Don’t worry. But come back and see me again. I always look forward to you. You are so kind.'”

The year after she recorded her story, Beatrice got a flat in the Boundary Estate but was subsequently found there, two weeks after she died, by social workers who had neglected to visit. “The Good Deeds of a Good Woman” is an alarming tale of how a woman can fall through the surface of existence and never regain control of her life, but it is also remarkably testimony of moral courage and tenacity to survive and, thanks to Clive Murphy, we can remember Beatrice Ali today with the respect she deserves.

Hardback copies of “The Good Deeds of a Good Woman,” including a vinyl record of Beatrice Ali talking, are available at Labour and Wait.

In Geoffrey Fletcher's footsteps

Hidden away behind the Genesis Cinema and Wickham’s lopsided department store is Bellevue Place. To get there, you walk up a side street from the Mile End Rd where you discover a bright green door in an old wall hung with ivy. Push this door and enter another world just as writer and artist, Geoffrey Fletcher, did when he walked through the same doorway in 1964.

In The London Nobody Knows he wrote,“A green gate opening in the wall leads to a totally unexpectedly corner of London, one that may well disappear if Charrington’s, who own the property, ever decide to expand. Bellevue Place is well named. It is a cul-de-sac with a paved pathway leading to the far end, under a creeper-covered wall. The cottages are early nineteenth century, and have true cottage gardens fenced with wooden rails, pointed at the top. Here are unbelievably rural gardens, full of lilac, lupins and delphiniums – all a minute’s walk from the Mile End Road.”

Geoffrey would be gratified to see my picture and learn that Bellevue Place remains today, its cottage gardens still fenced with wooden rails, pointed at the top. The irony is that Charrington’s has gone and the large brewery complex, of which the creeper-covered wall once formed part of its perimeter, has been replaced by a housing estate. Geoffrey Fletcher’s project was to record the quaint old corners of London before they were destroyed in the name of progress, but the popularity of his work marked a change in public opinion towards the preservation of buildings. As a result, many of those he recorded in elegiac tones in “The London Nobody Knows” are preserved today as characterful landmarks of the London everybody knows.

Bellevue Place, unseen from the street and surrounded on four sides by high walls, is a magical place where it truly does feel as if time has stood still. The walls form a wind break, creating an atmosphere of warm still air in the gardens and, each of the half-dozen times I have been there, I have never seen any of the residents. There is an innate quiet in this corner. As I searched to find the exact spot where Geoffrey Fletcher did his drawing, framed by lush foliage all those years ago, I should not have been surprised if he had appeared through the green gate or, equally, if I had walked out of the gate to discover I was in London in 1964.

Over in Spitalfields, Geoffrey deliberated over what to draw because even then people were catching on to the London nobody knows. “One of the finest eighteenth-century shops in the whole of London is here, in Artillery Lane. However, as this is well-known, I have chosen to illustrate a curiousity instead – the Moorish bazar in Fashion Street, given an odd realism by the turbaned figures of Indians who have drifted into the area. It was once a Jews’ market, a place for the sale of cheap textiles, penny notebooks, and fifty-blade penknives. Buildings with a Turkish, or Moorish touch invariably appeal to me, by their utter disregard of architectural qualities. I have a liking for the tawdry, extravagant and eccentric.”

The eighteenth century shop in Artillery Lane (which James Mason stood outside in the film of The London Nobody Knows) is now the Raven Row gallery and the Moorish bazar, after being derelict for many years, has been reconstructed, preserving most of the facade, as an office building occupied by media businesses. The integration of the facade of the bazar into the new building means it is more corporate than tawdry today. This is no longer the place for penny notebooks and fifty-blade penknives, though if Geoffrey came back he would not have to look far in the surrounding streets to find them.

You have to ask yourself who the “Nobody” of ‘The London Nobody Knows” refers to, because all the places he describes have inhabitants. How could the population of the East End rank as nobody? Given that Geoffrey Fletcher was a Daily Telegraph columnist, I choose to assume that by “Nobody,” he means “Nobody who reads the Daily Telegraph.” The implied title being, “The London Nobody who reads the Daily Telegraph Knows.” If you can forgive me being so disingenuous, let me quote the following extract from his introduction of 1962 – which regrettably sounds comically antiquated now – as evidence of my assumption, and leave you to your own conclusions, “There are parts of London never penetrated, except by those who like myself, are driven on by the mania for exploration: Hoxton, Shoreditch, Stepney for instance, all of which are full of interest for the perceptive eye, the eye of the connoisseur of well-proportioned though seedy terraces, of enamel advertisements and cast-iron lavatories.”

Even if he was capable of being a curmudgeon, we owe Geoffrey Fletcher a debt of gratitude for recording his fond appreciation of once neglected aspects of our city so conscientiously and with such lyricism. In fact, I cannot deny a twinge of jealousy that I was not around to visit these places as he described them, though I am lucky enough to have Bellevue Place nearby whenever I need a glimpse of his London.

By 1989, Geoffrey had become aware that “The London Nobody Knows” was a relative concept, an horizon that retreated endlessly and, in acknowledgement of this, he added a new preface including the words, ” Tomorrow, scorning the London everybody knows, we may take the road, like Mr Pickwick, eager for character and flavour, expecting only the unexpected. We may search for bankrupt tandooris in the uplands of North London. We may even set out for the Seven Sisters Rd…”

Spitalfields Antiques Market 3

This is Mike Leslie, ever-devoted husband, minding the stall for his wife Barbara whose business it is dealing in pawnbroker rings. Barbara Leslie has five hundred different rings for sale at approximately a quarter of the retail price, both antique and modern, and starting at £25. Mike showed me a diamond ring that would retail for £1,000 in the West End which he was selling for £200, and demonstrated the device that reveals the flaws in the gems, since only genuine diamonds have them. I was captivated by the drama of Mike’s display of glittering stones because I discern he understand that each one represents a chain of love stories, both in the past and yet to come.

This stylish couple are Charles and Tracey Darby who deal in taxidermy and possess a fine display of stuffed animals that return your gaze with frozen intensity. I was particularly attracted by the pair of squirrels which date from 1780. As well as selling antique specimens, Charles is a passionate taxidermist of the contemporary ethical variety and sells his own work too. Look out for the fox cub that was a victim of a hit and run, which the RSPCA gave Charles dispensation to stuff. “I grew up on a farm and my father taught me taxidermy at home from when I was ten years old,” confided Charles enthusiastically, “Years ago people used to love this kind of thing, then it went out of fashion but now it has come right back again.”

This is Jonny Mitchell, the handsome bookdealer with an eclectic left-field taste in literature, manifest in his collection of the works of Charles Bukowski, Jack Kerouac and other beat writers, plus related marginalia including Fluxus titles. It is a rare delight to come across a bookseller who has read his books and is as passionate about his speciality as Jonny. Be sure to check out his vintage erotica, comprehensive selection of Star Trek novels, pulp fiction by Dennis Wheatley and Ian Fleming, and fine selection of early Penguins too. You have to admit, Jonny knows how to wear a leather jacket with an ease that compliments his choice of books perfectly.

This is Estefi Vidal and Enric Jorba, two happy young Catalonians in love. After two years, their stall is no longer simply vintage clothing for sale, it is a full blown romance that last week burgeoned into an engagement. “It’s not just a job for us, the business is something that we do together. We’re a couple and it’s our love story. It would be hard if I had to do it by myself but, sharing the work with Enric, it becomes a pleasure,” explained Estefi with a smile. Then she flashed her engagement ring proudly and I wondered if it came from Mike and Barbara Leslie’s stall.

Photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman

Spinach & Eggs from Spitalfields City Farm

The old hawthorn at the Spitalfields City Farm was in full blossom under a blue sky to welcome me as I arrived yesterday morning in search of spinach & eggs, in anticipation of one of my all-time favourite lunches. At the far end of the farmyard, I was greeted by Helen Galland, the animals’ manager, whom I interrupted from her mucking-out duties to sell me half a dozen freshly laid eggs. I deliberated between hens’ and ducks’ eggs so Helen kindly gave me three of each, £1 for the lot.

The Spitalfields flock is a mixture of rare breeds (Marsh Daisies and Buff Orpingtons) and rescued chickens, bought by a charity from battery farms that would otherwise destroy the hens after a year’s life of producing an egg a day, when they still have another four to five years of life left laying eggs. “When they arrive they have to learn to be chickens because they have never seen anything but the inside of a cage before, so the first thing they do when they arrive is lie in the sun.” explained Helen with maternal sympathy, as the flock ran around our ankles pecking in the yard, “In factory farms, they have no nesting materials but they soon get the hang of it here.”

I stowed the half-dozen eggs in my bag and walked over to the other end of the farm where the vegetables are grown. Here, Chris Kyei-Balffour, a community gardener, led me into the humid atmosphere of one of the polytunnels to admire a fine patch of spinach that he grew, glowing fresh and green with new leaves in the filtered sunlight. To my delight, Chris picked me a basket of the most beautiful fresh spinach I ever saw and presented it to me. We shook hands and it was my privilege to buy this spinach for £1. Thanks to Helen and Chris, I carried my ingredients of spinach & eggs away for a mere £2. Anyone can buy produce at the city farm, you just have to go and ask. Let me admit, I was pulling out spinach leaves from the bag and eating them in the street, unable to resist their tangy sweet flavour, as I walked home, hungry to cook lunch.

Although spinach & eggs is one of the simplest of meals, careful judgement is required to ensure both ingredients are cooked just enough. It is a question of precise timing to ensure the perfect balance of the constituents. I steamed the spinach lightly while I poached the eggs in salted water. The leaves need to be blanched but must not become slushy because texture is everything with spinach, it needs to be gelatinous yet chewy.

Once the spinach was on, I broke three hens’ eggs, slipping them gently into a pan of simmering water and poached them until the white of the egg was cooked but the yolk remained runny. Be aware, you have to be careful not to break the yolks when you drop the eggs into the water and some concentration is required to master the knack of scooping then out intact too. I have ruined the aesthetics of my spinach & eggs on innumerable occasions with a casual blunder at this stage, though I can assure you the meal still remains acceptable to the taste buds even if you top your spinach with pitiful fragments of poached egg.

Yesterday, I served a generous portion of my delicious spinach in an old soup dish and – blessed with good luck – I balanced all three eggs on top, perfectly intact and wobbling like jellies. With eggs freshly laid that morning and spinach picked half an hour before I ate it, the ingredients could not have been fresher. No vocabulary exists to explain fully why I like this combination so much, it is something about what happens when you recklessly slice through the egg and the hot golden yolk runs down into the slippery seaweed green spinach. You have to try it for yourself because the combination of the sweet yolk and almost-bitter spinach is astounding.

With the addition of a little ground black pepper and grated parmesan on the top, I carried the spinach & eggs outside into the garden triumphantly, enjoying my lunch in the sunshine for the first time this year. The anachronism of eating my meal of ingredients fresh from the local farm, here in the secret green enclave of my garden in the heart of Spitalfields only served to amplify the pleasure. It was an unforgettable moment of Spring.

Chris Kyei-Balffour and his fine crop of spinach.

A Buff Orpington.

Kellogg the cockerell and a Marsh Daisy hen.

A refugee from a factory farm.

A Buff Orpington Bantam.

My lunch.

Isabelle Barker’s hat

Even though I took this photograph of the hat in question, when I examined the image later it became ambiguous to my eyes. If I did not know it was a hat, I might mistake it for a black cabbage, a truffle, or an exotic dried fruit, or maybe even a sinister medical specimen of a brain preserved in a hospital museum.

Did you notice this hat when you visited the Smoking Room at Dennis Severs’ House in Folgate St? You will be forgiven if you did not, because there is so much detail everywhere in this extraordinary house and by candlelight the hat’s faded velvet tones merge unobtrusively into the surroundings. It feels entirely natural to find this hat in the same room as the painting of the gambling scene from William Hogarth’s “The Rake’s Progress” because it is almost identical to the hat Hogarth wore in his famous self-portrait, of the style commonly worn by men when they were not bewigged.

Yet, as with so much in this house of paradoxes, the hat is not what it appears to be upon first glance. If it even caught your eye at all because it is so at home in its chosen spot that the gloom contrives to conjure virtual invisibility for this modestly austere piece of headgear – if it caught your eye, would you give it a second glance?

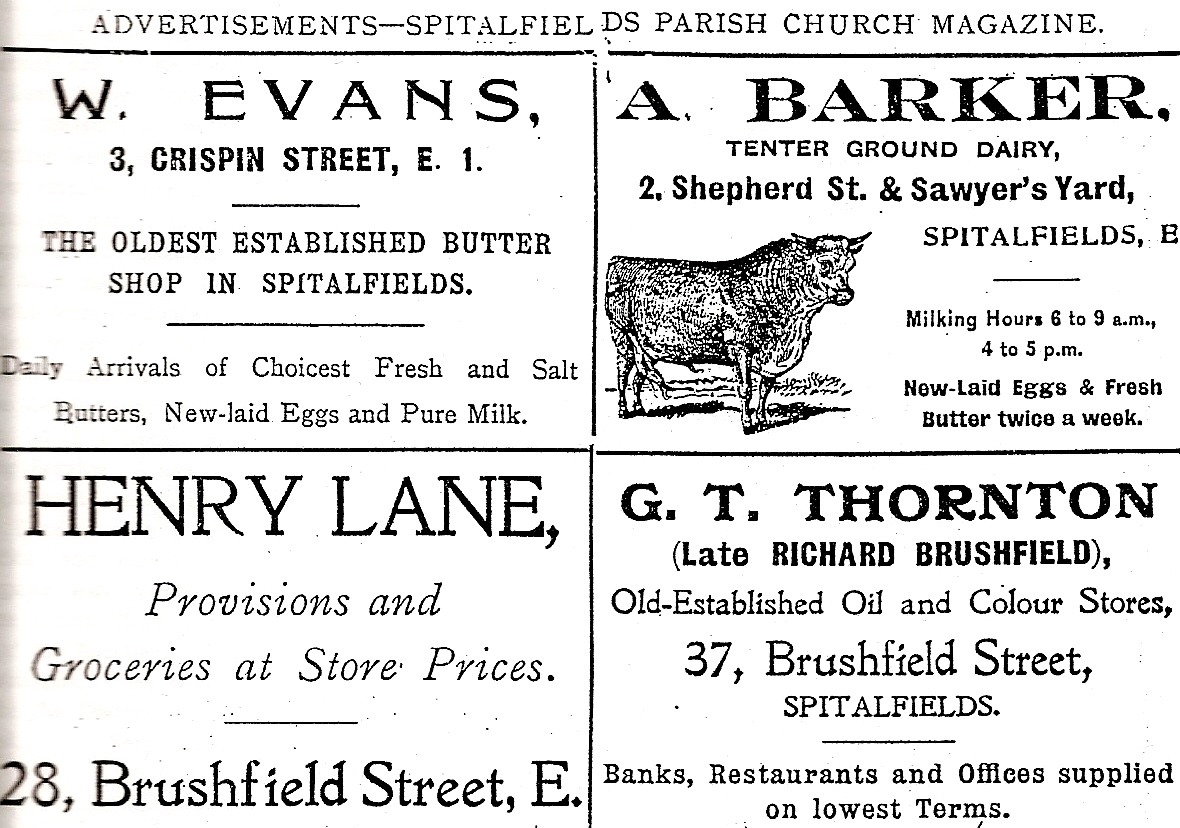

It was Fay Cattini who brought me to Dennis Severs’ house in the search for Isabelle Barker’s hat. Fay and her husband Jim befriended the redoubtable Miss Barker, as an elderly spinster, in the last years of her life until her death in 2008 at the age of ninety-eight. To this day, Fay keeps a copy of Isabelle’s grandparents’ marriage certificate dated 14th June 1853. Daniel Barker was a milkman who lived with his wife Ann in Fieldgate St, Whitechapel and the next generation of the family ran Barker’s Dairy in Shepherd St (now Toynbee St), Spitalfields. Isabelle grew up there as one of three sisters before she moved to her flat in Barnet House round the corner in Bell Lane where she lived out her years – her whole life encompassing a century within a quarter-mile at the heart of Spitalfields.

“I was born in Tenterground (now the site of the nineteen thirties Holland Estate), known as the Dutch Tenter because there were so many Jews of Dutch origins living there. My family were Christians but we always got on so well with the Jews – wonderful people they were. We had a dairy. The cows came in by train from Essex to Liverpool St and we kept them while they were in milk. Then they went to the butchers. The children would buy a cake at Oswins the baker around the corner and then come and buy milk from us.” wrote Isabelle in the Friends of Christ Church, Spitalfields, magazine in 1996 when she was a mere eighty-seven years old.

Fay Cattini first became aware of Isabelle when in her teens she joined the church choir which was enhanced by Isabelle’s sweet soprano voice. Isabelle played the piano for church meetings and tried to teach Fay to play too, using an old-fashioned technique that required balancing matchboxes on your hand to keep them in the right place. “I grew up with Isobel,” admitted Fay,“I think Isobel was one of the respectable poor whose life revolved around home and church. She had very thin ankles because she loved to walk, in her youth she joined the Campaigners (a church youth movement) and one of the things they did was to march up to the West End and back. She enjoyed walking, and she and her best friend Gladys Smith would get the bus and walk around Oxford St and down to the Embankment. Even when she was old, I never had to walk slowly with her.”

Years later, Fay and Jim Cattini shared the task of walking Isabelle over to The Market Cafe in Fournier St for lunch six days a week. In those days the cafe was the social focus of Spitalfields, as Fay told me,“Isabelle was quite deaf, so she liked to talk rather than listen. At The Market Cafe where she ate lunch every day, Isabelle met Dennis Severs – Dennis, Gilbert & George, and Rodney Archer were all very sweet to her. I don’t think she cooked or was very domestic but walking to The Market Cafe every day – good food and good company – then walking back again to her small flat on the second floor of Barnet House, that’s what kept her going.”

In fact, Fay remembered that Isobel gave her hat to her friend Dennis Severs, who called her his “Queen Mother” in fond acknowledgement of her innate dignity and threw an elaborate eightieth birthday party for her at his house in 1989. But although nothing ever gets thrown away at 18 Folgate St, when we asked curator David Milne about Isobelle Barker’s hat, he knew of no woman’s hat fitting the description – which was clear in Fay’s mind because Isabelle took great pride in her appearance and never went out without a hat, handbag and gloves.

“Although she was an East End person,” explained Fay affectionately,“she always looked very smart, quite refined, and she spoke correctly, definitely not a cockney. She had a pension from her job at the Post Office as a telephonist supervisor, but everything in her flat was shabby because she wouldn’t spend any money. As long as she had what she needed that was sufficient for her. She respected men more than women and refused to be served by a female cashier at the bank. Her philosophy of life was that you didn’t dwell on anything. When Dennis died of aids she wouldn’t talk about it and when her best friend Gladys had dementia she didn’t want to visit her. It was an old-fashioned way of dealing with things, but I think anyone that lives to ninety-eight is impressive. You had to soldier on, that was her attitude, she was a Victorian.”

When Fay produced the photo you can see below, of Isabelle with Dennis Severs at her eightieth birthday party, David realised at once which hat once belonged to Isabelle Barker. Even though it looks spectacularly undistinguished in this picture, David saw the hat in the background of the photo on the stand in the corner of the Smoking Room – which explains why the photo was taken in this room that was otherwise an exclusive male enclave.

At once, David removed the hat from the stand in the Smoking Room where it sat all these years and confirmed that, although it is the perfect doppelganger of an eighteenth century man’s hat, inside it has a tell-tale label from a mid-twentieth century producer of ladies’ hats. It was Isabelle Barker’s hat! The masquerade of Isabelle Barker’s hat fooled everyone for more than twenty years and, while we were triumphant to have discovered Isabelle’s hat and uncovered the visual pun that it manifests so successfully, we were also delighted to have stumbled upon an unlikely yet enduring memorial to a remarkable woman of Spitalfields.

Dennis Severs & Isabelle Barker at her eightieth birthday party with the hat in the background.

William Hogarth wearing his famous hat.

Barker’s Dairy as advertised in the Spitalfields Parish Magazine in 1923.

Fay and Isabelle in 2001

Albert Stratton, pigeon flyer

With the pigeon racing season commencing on 10th April, I took the opportunity of an introduction to the sport kindly extended to me by Albert Stratton, secretary and clock setter of the Kingsland Racing Pigeon Club, which has been established for over a century. Ever since I read Dickens’ description of the pigeon lofts in Spitalfields in 1851, I have been curious to discover whether anyone keeps pigeons here today. So I was delighted to find Albert in the garden of his house beside Weavers Fields in Bethnal Green, where he has two sheds filled with pigeons, and learn that the venerable East End culture of keeping homing pigeons is alive, nurtured by a small group of fanciers.

Albert is a powerfully built man with a generous spirit, who becomes lyrical in his enthusiasm when talking about these familiar birds that are as mysterious as they are mundane. Commonly considered pests, pigeons are so ubiquitous as to be almost invisible, yet if they were rare maybe we would prize them for their fine plumage and astounding navigational abilities – just as Albert does.

“When I was fourteen, growing up in Shoreditch, I was walking through the flats one day and there was a pigeon on the floor, as skinny as you can get. He had a ring round his foot, so I took him home and my dad said, ‘It’s a racing pigeon, you’ve got to let it go because it belongs to someone.’ Then we found it couldn’t fly, so he said, ‘We’ll keep it on the balcony and build it up until it can fly.’ But when we did let it go, it flew up in the air and back into the box – and after that I became fascinated with pigeons and how they will stay with you.

We moved to the Delta Estate and had a flat on the top floor with a big balcony, and when I found four Tippler pigeons (which are fancy pigeons not racers) abandoned, I took them home and kept them on the balcony in crates with wire netting on the front. I used to let them go out and fly, and they’d come back. Then, when we bought the house in Bethnal Green, we decided to keep racing pigeons. We built two sheds and had six babies delivered by courier from the Maserella stud in Leicester.

In 1983, I joined the Kingsland Pigeon Racing Club and my first year’s racing with them was 1985 and I won fourth place in the club which gets you into the prize money. And you think to yourself, anyone can do this – but you find out later, it’s hard. You’ve got to keep your pigeons healthy and fit – spot on. Sick pigeons can’t race. You’ve got to train them to build up the muscle and the fitness. Pigeon racing is like horse racing – the money is in the breeding not the racing. You pay to breed from the winners, studs buy up the winning pigeons and then sell off their young ones.

We start the season on 10th April at Peterborough, from there to my house is seventy-one and half miles. After that first race, we carry on in stages of thirty miles between each race point, moving up the country. Newark at one hundred and twelve and a half miles is the second race point, and after fifteen weeks we end up in Thurso at five hundred and seven miles North of here.

Before the race, we all go round to the club headquarters in Mr Hamilton’s garden, where we mark each pigeon with a numbered rubber band. Then we synchronise our clocks. Once the pigeon arrives home, you take the number off the leg and put it in the clock which stops the timer. The timing runs from the moment when the pigeons are liberated.

Pigeons fly at fifty miles per hour with no wind. So, if they are liberating the pigeons at nine o ‘clock in Peterborough, you check the weather and, if the wind forecast is thirty-five miles per hour from the North, then you estimate it should take approximately two hours, which means the pigeons will arrive in Bethnal Green at eleven. Once you’ve worked out a time of arrival, you are waiting for them. I’ve stood at the back door looking to the North and everything that moves in the sky you go, “Come on, come on!” – if it’s yours or not. You look at your watch and then back at the sky.

There’s nothing better than seeing one of your birds come out of the sky, when it folds to make itself small to become as fast as possible, because it wants to get home. As soon as it arrives, you go in the garden with peanuts to get his attention, so you can get the rubber band off and put it in the clock.

Then you go round to the club, where the rubber bands are collected and all the clocks are struck off against the master timer to confirm they are all the same. We know the exact time they left and the exact time they arrived, so we divide the distance by the time to get velocity and the bird that has the greatest velocity wins. We record our first ten birds which means everyone gets their name published in The Racing Pigeon, which covers all the East End clubs.”

I followed Albert into the shed to take pictures while he cleaned out the shelves and tenderly checking on those birds hatching eggs or nursing chicks, even holding up a tiny blind newborn chick in his large hand to show me, replacing it gently under its mother’s breast before it got cold, and then chasing the other pigeons outside to get some exercise.

When Albert joined the Kingsland Club in 1983 there were thirty members but now there are eight, the others have died or moved East towards Clacton, Albert says, and Kingsland itself is the only proper club left in Hackney where there once four or five. Today, there is one in Stepney Green and another in Wood Green, that is distinguished by its multiracialism. “Polish people might be the only lifeblood to save pigeon racing in this country,” commented Albert absent-mindedly from within the shadows of the pigeon shed, “If people don’t mix there’ll be no peace in this world.”

It is truly remarkable how these modest birds can navigate over great distances, and I was touched to observe the passion they draw from Albert, whenever the miracle is repeated, each time they fly home to him. Through pigeons, Albert in his small garden in Bethnal Green is connected to the wide landscape that the pigeons traverse to fly home and through pigeons Albert also is connected to the intense social life of the Federation of Racing Clubs, as the average for every pigeon accumulates through the season to arrive at a prize bird that can deliver a substantial reward.

While we were talking in the living room, our conversation was interrupted when we saw a cat appear on the roof of the pigeon shed and Albert rolled his eyes, “Look at that creature! Where’s my rifle?” he growled.

The Kingsland Racing Pigeon Club welcomes new members, if you are interested contact Albert by emailing him at stratton123@btinternet.com

Columbia Road Market 29

Through the drizzle I heard the cockerell crowing at the Spitalfields City Farm as I walked up to Columbia Rd where this Easter morning there was a lively crowd at the flower market by eight o’ clock. I deliberated between Rhubarb and Clematis before buying a tray of eight Violas for a mere £2. I love Violas with their delicate deep violet and white petals, half and half, like butterfly wings. They remind me of happy days in the Outer Hebrides where on the Isle of Barra they grow wild on the machair, the bank of seaweed built up at the top of the beach to create a narrow strip of land, that in Summer is as rich with tiny flowers as an Alpine meadow.

There is a small window above the stove in my kitchen that I open to expel the steam when I am cooking, this is where I raise my eyes in contemplation while I am stirring the porridge. On the sill sits a nineteenth century Welsh lustreware creamer that I bought in Exeter many years ago, and these Violas in this tiny box will make an attractive background to my beloved cow for months to come.