The Gentle Author Speaks

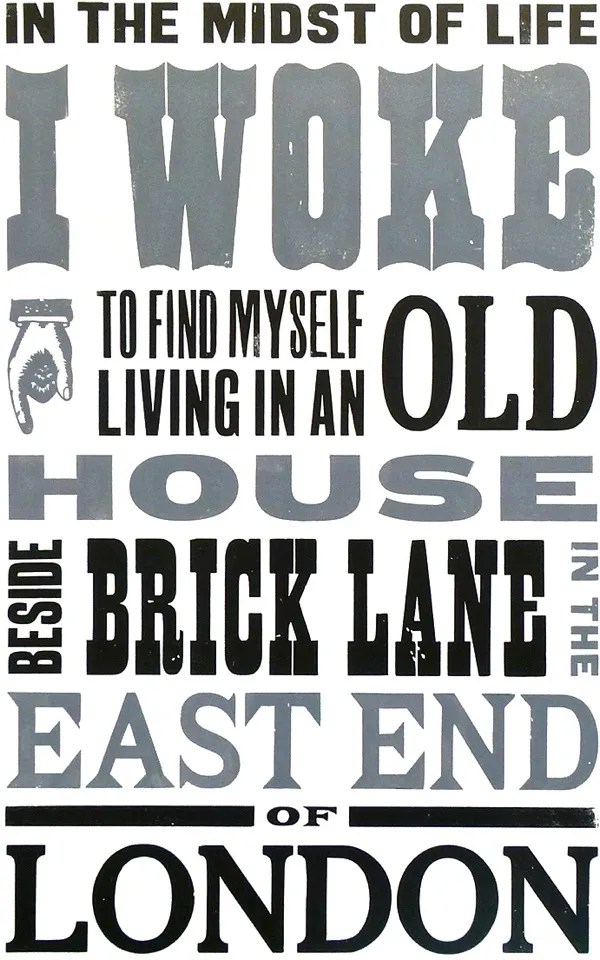

This interview, conducted and edited by Tim Rich, was first published last year in Random Spectacular, a limited edition magazine with a circulation of seven hundred and fifty, and I am republishing the piece today so that those who were unable to obtain a copy may read it here. The print which was commissioned to accompany the interview was created by Justin Knopp of Typoretum.

I wanted to find out more about the writer whose words transport me each day, whose stories take me through previously unseen doorways in my own neighbourhood in the East End. But that also required a promise from me – that I wouldn’t reveal the identity of The Gentle Author. I feared that this guarding of the person behind the pen might go hand in hand with a reticence to talk. What I encountered was something else entirely. Here are some of the words we exchanged over a pot of tea in East London.

Tim Rich – Your promise to readers includes a picture of a sundial on Fournier Street that features the words ‘Umbra Sumus’ – “We are shadows.” Reading your writing for the first time, I had the immediate feeling that you were either pursuing or escaping something.

The Gentle Author – Well, there’s a wonderful notion that Kierkegaard described – that being a writer is like being in the continual state of running through a burning house, trying to decide what to rescue. I do feel that sensation a lot of the time. Also, that people’s stories go unrecorded is a matter of grief to me. I think that arose after the death of my parents. I grew up in Devon around old people, and I used to knock on their doors and ask to spend a day with them. I suppose I have a vertiginous sense of all the stories in the world, and accompanying that is a sense of the loss of all the stories. So I have a compulsion to collect as many as I can, for as long as I can.

Tim Rich – Your stories became longer after a couple of months of the blog, and that coincided with you writing more pen portraits.

The Gentle Author – I have a personal sense of responsibility to people that I’ve met to do them justice. The idea of trying to sum someone up in a thousand words is terrifying. That was why the stories got longer and longer. The other thing that happened in the first year – unexpectedly – was that a lot of readers came along. It gave me a different responsibility, to not disappoint the reader. You want to give them something wonderful. So I became more ambitious.

Tim Rich – That is a terrific counterblast to the common, pessimistic notion that people don’t read much any more, and that writing for the Web should always be short. You show that the Web can be a place for a longer and more personal form of writing.

The Gentle Author – I respect the discipline of writing, that a piece should be well structured and a story well told. But I also aspire to write in an unmediated way, and to not withhold an emotionalism if that’s how I react to a subject. I am also attracted to use vocabulary in a way that it is not used in journalism, but is perhaps more common in fiction. I chose to be this voice speaking from the darkness, because I want to be in private with the reader. I want the reader to understand that the writer’s intention is benign, and that we can trust each other. And I hope the readers create their own sense of who they are listening to and take ownership of what they read. In this sense, the Gentle Author is a conceit to bring readers closer to the subject, and I want the subject to be the people I’m writing about, not me.

Tim Rich – Do you have to get into the character of the Gentle Author when you write?

The Gentle Author – Graham Greene said that reading Charles Dickens was like listening to the mind talking to itself. It is the internal voice that I aspire to in my writing – what I hear inside my mind.

Tim Rich – Tell me a little more about the ‘hare-brained’ task you have set for yourself.

The Gentle Author – I wanted readers to know they could rely on something new every day. And I felt that if I created this cage for myself, then I could have no escape. I have written more than 800,000 words in the last two years, so it has worked to that degree. It’s a miracle. I spend most of the day running around the streets after people and doing interviews. In the evening, I sit down to supper, and then I write. The golden rule is that I can’t go to sleep until it’s done. People sometimes think that I knock off six stories in advance and press a button each day, but it isn’t like that at all. I may write interviews up a few days later, but it appeals to me that the Gentle Author has no choice but to write a story every day. I’m aware that it’s an excessive way to live but my experience has taught me that life is excessive.

Tim Rich – Your interviewees tell you remarkable things about their lives. How do you earn their trust?

The Gentle Author – You have to be open-hearted and honest, and you hope people see that it is just you, and that there’s no ulterior motive – and that no one’s paying you to do it. That you are doing it for love. People are wisely suspicious of writers, so I commonly send someone a piece I have already written and they can see what the outcome of being interviewed will be like.

Tim Rich – You write about the tension between tradition and change, such as the spiraling rents that have threatened to push out merchants like Paul Gardner.

The Gentle Author – It’s very difficult to trace what’s a right or wrong way for change to happen, but it’s vital that good things don’t get destroyed. For me, Paul Gardner, the Market Sundriesman, incarnates the essence of Spitalfields. Unless you have gone and shaken hands with Paul Gardner you can’t really say you have been to Spitalfields. His shop is where all the small traders in East London go to get their bags. What happened in Paul’s case was that, after my story, the landlords relented in their original demand for an excessive rent increase and showed themselves to be enlightened, recognising he is a special case. I hope people appreciate that the things which make this place distinctive are worth holding on to. One of the lessons revealed by the crash in the City was that the short-term profit motive is destructive and people need to take a longer-term view.

Tim Rich – You seem to revel in those lively nights out with the Bunny Girls and the trannies and the boys’ club reunions, but how do you feel about Spitalfields on a Saturday night – the drinkers and clubbers?

The Gentle Author – I think it’s a beautiful phenomenon. I often go out and walk the streets just to see the crowds on a Saturday night. Nothing has changed much there. In the 1860s The Eagle Tavern on the City Road was getting 12,000 people turning up a night and there were complaints about the crowds then. I think the young people who dress up and come to show off their outfits on Brick Lane embody a wonderful flowering of culture. So many people compete for ownership of this place, but the truth is that it belongs to everybody and nobody. There is a magic in Spitalfields, but if you love the area you must also be generous to others who love it too.

Tim Rich – Will there be enough space in your life to do other types of writing, as well as your daily report?

The Gentle Author – Dickens wrote six or seven stories a week for Household Words, but he also wrote the novels of Dickens as well. My background is in fiction, and originally I envisaged that there would be a chapter of a novel by me on the first of the month through the year. That has been sidelined, but as I get more confident and more in control of what I’m doing it could resurface. I’m attracted to the idea that the Gentle Author might have fictional adventures.

Tim Rich – What about visits to other places far from Spitalfields?

The Gentle Author – I am a favoured person in that I have had so many experiences and lived so many lifetimes in my life already. I remember, I went to Los Angeles for the Millennium and I was with a friend in a car on New Year’s Eve, and we turned left onto the freeway into oncoming traffic. She said, “We’re going to die.” And I said, “I don’t mind because I’ve done so much in my life, but what about your son?” There are lots of places I would like to go back to – Beijing, Cuba – but what I do now forces me to live in the day. My mind is so crowded I don’t have much space to think about anything else.

Tim Rich – You said something curious in a story on Dennis Severs’ house, which was, “Much as I love a good chat, I have many times wished that I never had to speak again.”

The Gentle Author – I think talking is hard. We take people’s words to be the expression of who they are. But I have always felt, with me, that was a contradiction because I didn’t feel that in speech I could represent who I was. That was why I began to write, because by writing down I could wrestle with words and become more truthful to who I am. So yes, I think it would be wonderful if I could get through the rest of my life without talking. I once lived on an island in the Outer Hebrides. I was the only inhabitant and I had to row forty-five minutes to the shore to get my mail. I would not see people for months on end and I did so much writing then. Your internal monologue becomes much more apparent when all the interference of external conversations is gone. Walking is very important in that respect too. I long for the release of the mind.

Tim Rich – So, writing is a release from the deluge of thoughts in your head.

The Gentle Author – Yes. For me, the act of writing is writing it down. There are no drafts. Writing is the act of recording an internal monologue. Coming back to the notion of the mind talking to itself – for me writing is the outcome of an unquiet mind, I suppose.

Tim Rich – How has Spitalfields Life changed your life?

The Gentle Author – I walk down the street and sometimes people lean out of windows to wave and come out and shake my hand. It is a beautiful thing, yet for that to happen in the middle of this huge city is bizarre. Generally, I don’t understand why people don’t talk to each other more. I think this is a political construct, this situation where we are all alienated from one another. A book that was important to me as a student was Raymond Williams’ Culture and Society. I think one of the outcomes of mass distribution through the printing press in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was that it made everybody strangers to each other. We see all those people out there as ‘the masses’. It’s rubbish. It’s a lie. The hope of the internet is that it allows everyone to talk to each other again, and not be strangers.

Tim Rich lives in Bethnal Green and writes at www.66000milesperhour.com

A few copies of Justin Knopp’s print are still available from the Spitalfields Life online shop.

Noel Gibson, Painter

Railway footbridge at Poplar

You have only just a week – until 9th February – to catch the revelatory exhibition of Noel Gibson’s East London Street Scenes at the Tower Hamlets Local History & Archives in Bancroft Rd, which rediscovers an important painter from the nineteen seventies whose work has not been displayed for twenty-five years. These large paintings need to be seen in the gallery to fully appreciate the quality of impasto, with vivid black lines standing out in relief from the canvas and vigorous textures created with a palette knife, imparting a dramatic presence to these soulful visions.

Noel Gibson lived in the East End from 1962 until 1974 and the paintings in this show are the outcome of this period. Born in 1928 in Glasgow, Gibson originally trained as an opera singer and then became House Manger at the London Opera Centre based in the Troxy Cinema in Commercial Rd where he lived in a flat at the top of the building. A self-taught artist, he painted in the evenings after work.

“I began as an abstract painter but when I came to Stepney, I found paintings on my doorstep. Though I think there’s still a quiet abstract quality to my paintings. I am trying to express the spirit of the buildings, the strength of them and the people who were there. This is why I don’t put people into my paintings. People turn them into an episode with a background – but I am painting the background! I love these buildings. I walk the dog and I look at them at different times of day and in different weathers, and I keep going back. In a way I am making a record of a changing, I wouldn’t say a dying area, but often I go back to check up on a detail, a colour and a whole street has gone.” Gibson said in an interview in the Times in 1972.

Immensely successful in his day, enjoying acclaim and sell-out shows – one of which at St Botolph’s in Bishopsgate was opened by Tubby Isaac the jellied eel king – Noel Gibson was featured on BBC’s “Nationwide,” a popular current affairs programme in 1972. In 1974, he moved to South London, working at Morley College and appointed Provost’s Verger at Southwark Cathedral, yet in 1985 he admitted, “I regard Tower Hamlets as the area of inspiration for my work and I will always return to it.”

Noel Gibson died in 2006 and this collection of paintings, originally bought by Tower Hamlets Council in 1970 to be shown in public buildings, came to light when the borough’s art collection was being photographed – inspiring Anna Haward to curate this beautiful show that recovers a major painter of the recent, yet already distant, East End.

Hessel St – “If this street were in Paris, everyone would have wanted to paint it.”

Brick Lane, looking north towards the Truman Brewery

St Anne’s, Limehouse

St John’s Tower

Small Red House in Bow

Street Scene in Poplar

The Victory in Poplar

Chilton St, Spitalfields

Tower House, Fieldgate St, Whitechapel

Arbour Sq

Noel Gibson

Images courtesy of Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives

You may also like to read about Marc Gooderam, Painter

Rosie Dastgir, Novelist

Rosie Dastgir in Whitechapel Market

Rosie Dastgir lived in Ashfield St in the shadow of the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel for ten years from 1995 – 2005, and while she was there she began to write a novel. Then she went to live in Brooklyn, New York, but five years later completed her debut novel A Small Fortune, set in Whitechapel and Spitalfields, which is published this week in London. Yesterday, Rosie returned to the East End to take a stroll around her old territory for an afternoon of contemplation before publication day on Wednesday, and I enjoyed the privilege of accompanying her.

“The story was inspired by being in Whitechapel and the characters I met there,” she admitted to me as we walked down Brick Lane together, hunched up against the cold, with the minaret looming overhead,“I took a trip to Pakistan with my father in the nineteen eighties and then later – after he died – at the time of 9/11, I wondered what he would have made of the changes in the Islamic World.” Rosie’s novel is a bitter-sweet comedy about a British Muslim – inspired by her father who emigrated from Pakistan in the 1950s – a man who is losing control of his life and his family, as his daughter is dropping out of medical school at the Royal London Hospital and his cousin is failing as an East End estate agent.

“This is my old stomping ground,” announced Rosie with a murmur of delighted recognition as we turned the corner into the Whitechapel Rd. Then, crossing Altab Ali Park – “No matter how much money they spend on this place it will always resist gentrification,” she reassured me. Rosie’s father came to stay with her in Whitechapel in his final years.“When he died, I found a stash of his letters and diaries talking about Islam,” she revealed, adding that her novel is set in the early 2000s, after her father’s death, thereby defining a precise line between his experience and her fiction.

“I thought, ‘What am I doing, writing this in Brooklyn?'” declared Rosie, rolling her eyes humorously, “I already had the idea for it in Whitechapel and I had written a few chapters.” Her perseverance was rewarded when she found an American publisher for her novel before a British one. “That was a wonderful moment,” she confided with a modest smile, “because I had thought, ‘Maybe no-one’s going to get this?’ but it confirms this is a story that is appropriate to many cultures. It stands upon its own terms.” In retrospect, Rosie recognises that the geographical distance granted her a perspective, liberating her to write fiction.

Weaving through the narrow streets, we came upon Ashfield St and Rosie’s former house. “They haven’t even repainted the front door!” she declared in surprise, turning her back on it in disappointment to point out the houses of friends that once lived here. “I was pregnant at the time and when I saw another pregnant woman in the street, I said to her, ‘We must be friends because we’re both going to have babies!'” she told me with a grimace at the craziness of it. In spite of the chill of the afternoon, Rosie showed a buoyant energy and humour that is reflected the quality of her lively compassionate writing and graceful prose style. We sat together on the swings in Ford Sq and Rosie wondered at the gleaming new hospital tower that has sprung up since she lived here, while boys in white jalabiyas played football around us.

This is a year of significant change for Rosie, publishing her first novel and returning this summer to live in London. “I like my life in Brooklyn, but my eldest daughter is reaching thirteen and you come to the point where you need to make a decision,” she said, in quiet contemplation as we walked back towards the clamour of Whitechapel Market. Yet Rosie Dastgir’s journey has been more than simply trans-atlantic, she returns as a novelist with a distinctive voice and an outstanding first novel under her belt – and all the possibilities that fiction has to offer laid out before her.

A Day in the Life of the Chief Yeoman Warder at the Tower of London

John Keohane

Chief Yeoman Warder John Keohane wakes at 6:45am in his quarters in the Old Hospital Block and the first sight to greet his eyes as the daylight comes into focus is the mythic White Tower, gleaming in the dawn outside his bedroom window. At 7:50am each morning, trim in his Tudor uniform, he steps from his blue front door and crosses the Inner Ward of the Tower, walking down Water Lane between the ancient stone walls to reach the octagonal office in the twelfth century Byward Tower. Here John assesses the duties of his thirty-seven fellow Warders for the day, before commencing the Opening Ceremony of the Tower at 8:50am, when a contingent of soldiers in bearskins accompany him to unlock the heavy black gates at 9:00am precisely and admit the tide of visitors whose flow is as ceaseless as the Thames.

And so it has been for many years at the Tower of London. And so it was last week, when Spitalfields Life Contributing Photographer Martin Usborne and I accompanied John for a day. And so it will be today.

Only it will not be so tomorrow – because this is John’s last working day in the post of Chief Yeoman Warder. And thus the day that Martin and I shared with John was both an echo of all the other days, yet underscored with a certain poetry by the imminent conclusion of John’s time at the Tower – where he has been a Yeoman Warder since 1991.

Once John had ensured the Opening Ceremony had been completed with the essential aplomb that such rituals at the Tower require, we all strode up the hill past Tower Green to John’s Office in the Waterloo Barracks which he now shares with his successor and protégé Alan Kingshott, the current Yeoman Gaoler. Instantly, the two slipped into the freewheeling Morecambe & Wise style banter that characterises their relationship. “I just want to check my emails,” pleaded John in mock petulance, as we all piled into the tiny room and Alan vacated the work station. “I can’t get used to this desk,” John continued, squeezing himself and his voluminous Yeoman Warders’s uniform behind Alan’s newly installed office furniture with feigned distaste,“he’s got one of these ergonomically-shaped keyboards.”

“When I first arrived he was my mentor, he taught me everything,” confessed Alan reverentially, changing tone to add playfully,“It’s his fault I’m here!”

“I’ve written six pages of notes for him of things not to forget,” John confided to me to while Alan took the opportunity to get out the Brasso from a filing cabinet and polish up his belt buckle as John tip-tapped at his keyboard with one hand, stroking his beard in thought with the other. “John cleans his buckle every day,” Alan whispered to me. “And my shoes,” added John without lifting his eyes from the keyboard.

With free time on his hands, John took us on a tour of the casements, as the dwellings built into the walls of the Tower are called. Here, in the private areas of the Tower, live forty-seven families and washing lines and flower pots, even a doctor’s surgery, attested to their presence. Yet these spaces carry history as the original location of the Royal Mint and of the shooting range where Josef Jacobs, a German spy who was the last to be executed at the Tower, was shot in 1941. During his time, John has become increasingly drawn to study the events that happened here and out of all the locations it is the Bell Tower where Thomas More was imprisoned that touches him most. “It is just a bare room with a stone floor and a garderobe in the corner,” said John,“where they kept him for three months in 1543 before they took him out to Tower Hill and beheaded him. One of things that strikes me about it, the temperature is always the same. You always feel how cold it is.”

This is John’s special quality – through engaging with the past on a personal level, he has come to embody the soulful history of this place and because of his presence, and that of his fellow warders, visitors are able to appreciate the reality of the human history that has been enacted here among these monumental structures.“It’s been the epitome of my career,” John confessed to me as we sat in his quiet living room looking out onto the Inner Ward, where he once came as a ten year old child on a visit and then returned in 1972 as a young soldier on temporary duty at the Tower – though he never anticipated the part that the Tower would eventually play in his life. “I’ll miss living here,” he admitted to me, “but the house I have in Paignton is on a hill looking out across the sea towards Brixham.”

We joined the tourists in the cafeteria next door for lunch before ambling back to the Byward Tower for the Ceremony of the Word at 3pm, in which a contingent of soldiers from the barracks at the Tower collected a wallet with the password that is changed daily, necessary so the guard may know who can be admitted in case of an emergency. Then it was back to John’s office to await Mr Barley, a dapper gentleman who is a veteran of fifty-four years at Mappin & Webb, bringing John’s engraved silver salver that will remain to commemorate his time at the Tower. John scrutinised the simple text and found it satisfactory.

Already the January afternoon light was fading and it was time to prepare for the Closing Ceremony, as the Warders shepherded the sparse visitors from each of the buildings and John made the rounds collecting the bunches of keys, until the last stragglers left the Byward Gate and Warder Chris Skaife rang the bell high in the tower at 5:00pm. Later, at 10:00pm, the Ceremony of the Keys would ensure the final lockdown at the Tower. And tonight, after more than twenty years, it will signal the end of John Keohane’s tenure.

“The Tower is closed now and my day is over,” he said simply as we shook hands. It was a day in the life of the Chief Yeoman Warder at the Tower of London.

Waiting to open the Tower for the day.

Opening the gates at the Byward Tower to visitors.

John Keohane with Alan Kingshott who will succeed him as Chief Yeoman Warder.

John steps out of his front door.

John wakes each morning to the sight of the White Tower.

John stands for pictures taken by schoolchildren.

John eats a bowl of soup for lunch among the tourists in the cafeteria.

John takes delivery of the salver from Mappin & Webb commemorating his time at the Tower.

The silver figure of John presented to him as a leaving gift by the Tower.

John collects the keys from his fellow Yeoman Warders.

Chris Skaife ringing the bell at the closing of the day.

John Keohane – “The Tower is closed now and my day is over”

Photographs copyright © Martin Usborne

Residents of Spitalfields and any of the Tower Hamlets may gain admission to the Tower for one pound upon production of an Idea Store card.

You may also like to read about

Alan Kingshott, Yeoman Gaoler at the Tower of London

Graffiti at the Tower of London

The Beating of the Bounds at the Tower of London

The Ceremony of the Lilies & Roses at the Tower of London

The Bloody Romance of the Tower with pictures by George Cruickshank

John Keohane, Chief Yeoman Warder at the Tower of London

The Newspaper Distributors of Old London

When Spitalfields Life Contributing Photographer Colin O’Brien was growing up in a slum tenement in Clerkenwell in the nineteen forties, his mother used to give him a penny and send him out to buy a copy of the Evening Standard. Since 1827, the streets of London echoed to the cry of “Standodd! Midday Special! Standodd! Evening Special!” and, at its peak, there were over seven hundred distributors sending the paper as far afield as Liverpool and Brighton. Yet by the time the Evening Standard became a free paper two years ago, there were just one hundred and sixty distributors and today there are only sixty left. So when a handful of heroic distributors from the glory days of the Evening Standard gathered at the Bishopsgate Institute on Saturday for old times’ sake, I asked Colin to be there to take their portraits.

“I used to be a paper boy when I was at school in Catford in 1962.” recalled John Cato who worked for the Standard until 2008, “And when I left school at fifteen in 1965, the guy who delivered the Evening Standard asked me if I’d like to be his van boy. I had to be at the station to collect the papers at ten and I’d go off with him in the van to deliver and collect the money from the sellers. Then I’d go home for lunch and at two o’clock there’d be another driver I worked with to deliver the later editions. We got paid weekly, so on Friday I’d go back to Shoe Lane with the driver to collect my wages and I used to mix with the other van boys and we all made friends. Sometimes we used to socialise with the van boys from the Evening News, even though they were our competitors.”

It was a furious business, bundling up the papers and tying them up with string as they came off the printing presses in Shoe Lane, then sending them off continuously in the fleet of vans as the editions updated through the day. Years now after they retired, most of these men still have the ink-stained hands and backache that are marks of a lifetime in newspaper distribution.

Frank Webster started as a rounds boy, delivering papers to newsagents by bicycle four times a day.“I was thirty years old before I graduated to a driver,” he told me with shrug, “they said it was the longest apprenticeship – in fact, it was a bit of a closed shop, the families knew each other for generations. You needed a relative in the business to get a job and it was based on seniority, it was dead man’s shoes. Yet I always enjoyed going to work, being outdoors and meeting all the vendors, they were such characters.”

“Most of us took early retirement between 2007-2009 when they were trying to cut costs, before they sold the paper to Alexander Lebedev for £1 and it went free,” explained Rob Dickers with a philosophical grin. He started at fifteen and his father worked for thirty years as a compositor at the Standard since before World War II. “From the late sixties, there was a great sense of camaraderie but when the printing moved out from Shoe Lane to Rotherhithe and we were deunionised, the money dropped.” Rob and his pal John Cato were very active in the Chapel, as the branch of the union was termed. “I became Father of the Chapel, the shop steward,” revealed John, “The management de-recognised the union but I built it up again from three to eighty. That’s my claim to fame really.” John’s efforts ensured his members received better pensions and redundancy deals, crucial for the employees as the industry itself began to flag.

The retrospective irony is that while the newspaper managements enacted aggressive policies upon their workforce to drive costs down during the last decades of the twentieth century, in this century the entire newsprint industry finds itself eclipsed by electronic media. Yet these proud men are the last of a hardy breed who devoted their lives to keep the papers rolling and then fought fiercely against tyrannical employers to protect their livelihood as the world changed around them.

On this very day, the printing of the Evening Standard moves from Rotherhithe to Broxbourne and the first issue of the London Evening Standard not printed in London hits the streets this morning. As a new chapter opens for the capital’s most famous paper, the implications of this new development are yet to be discovered. No longer is the cry of “Standodd! Midday Special! Standodd! Evening Special!” to be heard upon the streets of London, and the soul of the city is the lesser for it.

Victor Wilson, Distributor at the Evening Standard, 1972 – 2007.

Frank Webster, Distributor at the Evening Standard, 15th August 1966 – 30th September 2007.

Ron Chadwick, Distributor at the Evening Standard, 1963 – 2006.

Former Evening Standard headquarters at Shoe Lane.

David Patten, Distributor at the Evening Standard, 1966 – 2009.

John Cato, Distributor at the Evening Standard, 1965 -2008.

Peter Steward, Distributor at the Evening Standard from 1964.

Brian Eller, Distributor at the Evening Standard from 1970 -2008.

Rob Dickers’ Newspaper Distributor’s knife. The notch on the top knife was worn by winding string around the handle to tie the bundle. “They wouldn’t let you go to work without one of these and a union card,” said Rob.

Rob Dickers, Distributor at the Evening Standard, 1966 – 2010.

Barry Pach worked in the Bill Room at the Evening Standard from 1960 – 1989, writing the bills for the newspaper hoardings by hand.

Portraits and final photograph © Colin O’Brien

Archive images courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute

Columbia Road Market 75

“No enemy but winter and rough weather…”

Every year at this time – the low ebb of the seasons – I go to Columbia Rd to buy potted bulbs and winter-flowering plants which I replant into my collection of old pots from the market and arrange upon the oak dresser, to observe their growth at close quarters and thereby gain solace and inspiration until my garden shows convincing signs of new life.

Each morning, I drag myself from bed – still coughing and wheezing from winter chills – and stumble to the dresser in my pyjamas like one in a holy order paying due reverence to an altar. When the grey gloom of morning feels unremitting, the musky scent of hyacinth or the delicate fragrance of the cyclamen is a tonic to my system, tangible evidence that the season of green leaves and abundant flowers will return. When plant life is scarce, my flowers in pots that I bought for just a few pounds each at Columbia Rd acquire a magical allure for me, an enchanted quality confirmed by the speed of their growth in the warmth of the house, and I delight to have this collection of diverse varieties in dishes to wonder at, as if each one were a unique specimen from an exotic land.

And once they have flowered, I place these plants in a cold corner of the house until I can replant them in the garden. As a consequence, my clumps of Hellebores and Snowdrops are expanding every year and thus I get to enjoy my plants at least twice over – at first on the dresser and in subsequent years growing in my garden.

Staffordshire figure of Orlando from “As You Like It.”

Old Town Small Trades

Francis in the role of Newsvendor.

Let me admit to you, I do not know how I could have got through these last two winters without the sturdy tweed trousers that Marie & Will at Old Town made for me. When I visited them in their modest workshop at Holt in Norfolk to collect my trousers, they showed me a book of Irving Penn’s “Small Trades,” dignified studio portraits of artisans and tradesmen taken in the 1950s. And last weekend, Marie & Will came down to Spitalfields to create an entirely new set of Small Trades commissioned from photographer Scott Wishart.

Taking over a first floor room in Fournier St, they borrowed baskets from Leila’s Shop, feather dusters from Labour & Wait, and co-opted friends and local characters to assume the roles of the tradesmen and women, all dressed head-to-toe in Old Town clothing. These garments draw their inspiration from classic twentieth century workwear, yet now that almost all casualwear is termed “workwear” Marie & Will sought a means to illustrate the provenance of their clothes, which are derived from actual working clothes and can be worn for work.

When Francis Wheatley painted the most famous set of the Cries of London in 1790s, all featuring his wife in the roles of the different hawkers to be found around Covent Garden, he initiated the tradition of these staged portraits of working people, of which these pictures propose the latest example. Readers may recognise some of these individuals – Jim is actually a Carpenter and Barry is a Barber operating from Andrew Coram’s Antique Shop in Commercial St, but I leave you to puzzle out the rest for yourself.

Sonia in the role of Archivist at the Department of Circumlocution

Jim in the role of Carpenter.

Harvey in the role of Waiter.

Twins Lee & Lisa in the role of Housekeepers.

Chris in the role of Costermonger.

Miss Willey and Old Brown in the role of Tea Stall Proprietors.

Izzy in the role of Flower Girl.

Barry in the role of Barber.

Bommer & Appleton in the role of Piano Movers.

Photographs copyright © Old Town

You may also like to read about