Five Hundred Eccles Cakes

Justin Piers Gellatly, heroic leader of a secret order of baker knights

How long would it take you to make five hundred Eccles cakes? A day? A weekend? Or, would the first ones be stale by the time you had completed the job? Yesterday, I walked down across Tower Bridge in the spring sunshine to visit Justin Piers Gellatly, head baker at the St John Bakery in Druid St, Bermondsey, as he was making the five hundred Eccles cakes for tonight’s launch party at Christ Church. I did wonder how long it might take yet I discovered that – such is his expertise and facility – Justin can make five hundred Eccles cakes in an hour.

“The boys are good,” he said, giving due credit to his fellows,“but I have made a lot of Eccles cakes in my time. I have nimble fingers and cold hands which really helps – if you’ve got hot hands you can get into trouble with the puff pastry melting.”

I found Justin at the rear of the railway arch beneath the main line out of London Bridge, where the bakery moved from Spitalfields a little over a year ago. At St John Bread & Wine, he operated from a corner of the kitchen, taking the place over at night once the last diners had left, but here he has expanded to fill the entire arch and, with a staff of five, the baking continues twenty-four hours a day. Last year, Justin won the accolade of baking bread for the royal wedding breakfast, and nowadays he supplies forty restaurants, and you can buy his bread at Neal’s Yard Dairy and Selfridges too.

Already, the white-painted arch has changed colour as a result of all the activity within, imbuing it with a golden tinge that manifests the romance of this hidden endeavour – undertaken in a tunnel resembling a magic cave, where Justin presides like the heroic leader of a secret order of baker knights.

When I arrived, Justin had five hundred patties of the filling for Eccles cakes laid out waiting upon a tray of greaseproof paper. Shaped like hockey pucks, these are formed from a mixture of raisins, Muscovado sugar, butter, all spice and nutmeg. On the other side of the table, Justin had rolled out large slabs of puff pastry made to his own recipe and in no time at all he riddled it with as many holes as a gunslinger in a Western, by cutting out circles with his cookie cutter. Justin’s puff pastry, which bakes to a tasty flakiness, is an unapologetic departure from the cakes you will find at Eccles that are made with suet pastry.

Working assiduously, Justin folded the discs of pastry around the filling and then laid them carefully upon a tray, making three cuts in each one – symbolising father, son and holy ghost – before coating them with an egg glaze and sprinkling them with caster sugar. Next, Justin put his babies in the convector oven for fifteen minutes, giving time to pay attention to the raspberry jam he was making for doughnut filling and the granola he was crisping in the bread oven.

I discovered my five hundred Eccles cakes were an inconsequential challenge for the man who makes a thousand every week, as well as closely supervising all the bread and cakes that are produced here. Every day, I eat Justin’s brown sour dough bread, and his doughnuts and Eccles cakes are regular treats, with mince pies and hot cross buns in season. Thus the good things from this bakery have become an inextricable part of my life.

Others may strive fruitlessly to reinvent the wheel but – among his myriad achievements in baking – Justin has excelled at the rather more profitable ambition of reinventing the doughnut. Something that existed in the folk memory as the incarnation of sweet deliciousness had been ruined by mass-production and synthetic jam, until Justin started making his custard ones at St John and restored the doughnut to the pantheon of cakes for a whole new generation. Yet, where once Justin used to make forty on a Saturday at St John Bread & Wine, creating intense competition among residents in Spitalfields to get there before they sold out, now he makes six hundred that sell out equally quickly to the eager customers of Maltby St.“Our biggest thing is doughnuts – it’s a phenomenon!” he admitted to me, unable to resist swelling with pride, “People come up to me in the street and call out, ‘You’re the doughnut man!'”

Just as Justin said this, the oven beeped loudly interrupting our conversation, as if the Eccles cakes wished to remind us they were the centre of attention that day. Once Justin opened the oven, a wave of sugary aroma hit me and when he pulled out the tray, I saw a transformation had occurred. The dumpling-like parcels of pastry were reborn as the golden shining orbs of sweetness we call Eccles cakes. By the time I left the bakery, five hundred were ready and Justin told me he had even managed to get a rare night off too – so now we are all set for the launch party this evening.

Raisins, Muscovado sugar, butter, all spice and nutmeg.

Cases made of puff pastry from Justin’s personal recipe.

Sprinkling caster sugar

Justin puts the Eccles cakes into the oven. (Note the first sighting of hot cross buns this season.)

Justin was also making raspberry jam for doughnuts.

Turning the tray before cooking for a further five minutes to ensure the Eccles cakes are evenly baked.

An Eccles cake by Justin Piers Gellatly.

You may also like to read about

Night in the Bakery at St John

The Bread, Cake & Biscuit Walk

The Tart with the Heart of Custard

On Publication Day

[youtube FunIes3ff2I nolink]

“An elegantly presented, generous and good-natured book, it offers an antidote to the sense of disconnection a big city such as London can engender. A city is its people and here they are celebrated in a way that will resonate beyond the East End.”

Carl Wilkinson, Financial Times, 24/02/2012

“…these wonderful stories shine anew in an attractive, beautifully illustrated book format. We can’t recommend it highly enough.”

Matt Brown, Londonist, 28/02/2012

Click here to buy your copy direct from Spitalfields Life and have it signed or personally inscribed by the Gentle Author.

David Pearson, Designer

“I’ll do this to the day I die if I’m allowed to!”

This man is so busy that the only way he can keep still is to sit on his hands. He is David Pearson, a designer who has been responsible for some of the most distinctive books produced in recent years, and it was my good fortune that he chose to apply his talents to designing the book of Spitalfields Life. I needed someone who could find a way to let my stories be at home upon the printed page and David rose to the challenge superlatively.

Over the last year, there have been innumerable trips over to his long narrow studio in Back Hill, Clerkenwell – the traditional home of printing in London – as David’s ideas have evolved until, at the very beginning of this year, we arrived at the complete volume in which one hundred and fifty stories, three hundred pictures and innumerable illustrations all fit together to become one four hundred and fifty page book with its own unity of purpose. Now that the mighty task is done and we can draw breath at last, I took the opportunity to make a return visit and enquire more of David’s rare clarity of vision.

Starting as a junior text designer at Penguin as recently as 2002, David was given the job of selecting the titles for a history of the company’s cover designs. In two weeks, he went through the entire sixty year archive, taking each one off the shelf for two seconds and replacing it again. Not only did “Penguin By Design,” the book David compiled and designed, achieve unexpected popular success, reaching a readership far beyond aficionados of publishing history, but the research that he undertook granted him a unique and inspiring insight into the evolution of book design in this country.

“Everything I have done since has been based upon an application of that to my own work,” he admitted to me with blatant modesty and an easy relaxed smile, “Good design is about refinement and details – I’ve learnt it’s ok not to reinvent the wheel.”

On the basis of “Penguin By Design,” David was given the job to design the covers for Penguin Great Ideas, an experimental series of low-budget books with two-colour covers. “I’m not an illustrator and I can’t take photographs, so I decided to do all the covers with type,” explained David, almost apologetically. Yet David’s famous landmark designs for these books, derived from his knowledge of the history of Penguin covers, were a model of elegant simplicity that stood out in bookshops and sold over three million copies. “I saw people picking them up and they didn’t want to put them down!” he confided to me, rolling his eyes in delight, “They were a phenomenon.” Then he placed a hand affectionately upon a stack of copies of this series for which he has now designed one hundred covers.

“I was only ever good at one thing, I used to finish off other people’s drawings for them at school,” he revealed to me suddenly, looking up as he retreated from his previous thought, taking me back to the beginning by recalling his childhood in Cleethorpes and adding, “I decided not to be an artist because I always need a brief or I flounder, so instead I trained to be a designer.” David’s disarming self-effacement is entirely in contrast to what I had expected, knowing him only through his bold designs.

It was on the basis of David’s brilliant typographic covers for the Great Ideas series, that I leaped at the chance of having him take on Spitalfields Life – because I wanted a designer who could work with classic type in a modern way and create something with an attractive utilitarian quality, reflecting the contents and subject of the book. Before I met him, I braced myself to encounter a fierce typographer with an authoritarian manner but – to my surprise – there was David, chuckling like a schoolboy, and with his corkscrew curls and plain features resembling a saint that just stepped off the front of a Romanesque cathedral, and lounging comfortably with his lanky limbs outstretched.

For interest’s sake I sent David a copy of a page of Dickens “Household Words” from 1851, as the closest precedent I knew for a collection of short literary pieces. Dickens published these weekly and for tuppence his forty thousand readers in London received a pamphlet of half a dozen stories every Saturday morning – a publication that today would almost certainly be a blog. When David saw this, he decided to adopt the same two column structure for Spitalfields Life, recognising that this format brought a pace and a dynamism to the flow of the type, and the font he chose was Miller by Matthew Carter, a redesign of a Scotch Roman face of a century ago which possesses subtle details, and that he characterised as “resolute.” What most appeals to me about David’s designs is that they do not look “designed,” they look as if they arrived how they are naturally and the success of his work on Spitalfields Life means that I could not now imagine the book any other way.

Like me, David likes to work late into the night when the phone stops ringing and the emails cease. “It’s a way to be able to pay attention to everything to the Nth degree,” he confided to me, “I can’t work quickly.” In spite of his success, David works long hours and weekends in his tiny studio where he has been established for the past three years. “I’ll do this to the day I die if I’m allowed to!” he declared to me candidly, almost in a whisper.

David Pearson’s beautifully proportioned title page for Spitalfields Life.

Charles Dickens’ Household Words provided the inspiration for David Pearson’s page design.

David Pearson’s page design for Spitalfields Life.

David Pearson’s page design for Spitalfields Life.

David designed this book and compiled the covers.

David’s redesign of the penguin for Penguin Books.

Artwork by Phil Baines

Illustration by Joe McLaren

Cover design by David Pearson, Staffordshire dogs by Rob Ryan.

You may also like to read about

The Spitalfields Suite by Lucinda Rogers

Commercial St and Spitalfields Market

One of the joys of compiling the book of Spitalfields Life was the opportunity to commission a suite of six large detailed drawings of Spitalfields from Lucinda Rogers to be published as double-page spreads, interspersing my stories with vibrant images of the life of the streets. An exhibition of these magnificent original drawings for the book is at Rough Trade East in the Truman Brewery from now until April 1st and – as an exclusive bonus – anyone that buys a copy from Rough Trade gets a handsome set of six cards of these views included. Three of “The Spitalfields Suite” are reproduced here followed by my original profile of Lucinda Rogers which offers a retrospective of her work in the East End.

Brick Lane with the Brick Lane Mosque Minaret.

Fournier St

Lucinda Rogers’ original drawings of Spitalfields are on display at Rough Trade until April 1st.

Even before I met her, I always admired this view looking West over Spitalfields by Lucinda Rogers that is framed on the wall of the Golden Heart in Commercial St. It is a large drawing executed in vigorous lines placed with superlative confidence, and filled with subtlety and fluent detail to reward the eye. The pale cloud on the horizon high above the City – illuminating the grey Northern light of a London sky – is a phenomenon that anyone in Spitalfields will recognise. What I especially like about this drawing is that there are so few lines, enough to summon the drawing into existence yet without any superfluous gesture. And although there is no pretence to photographic realism, the vivid spatial quality is such that when you gaze into the deep spaces of the composition it can feel almost vertiginous, especially if you have had a few drinks.

The next work of Lucinda’s to impinge upon my consciousness was her portrait of Paul Gardner, which hangs up behind the counter at Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen in Commercial St, where his family have traded from the same building since it was built in 1870. Here you see Paul, in his world composed of paper products, at ease behind the counter in a characteristic pose of dreamy contemplation, ever expectant of the next customer to burst through the door demanding paper bags. The crowded symphonic detail of the bags and tags and signs in this masterful portrait manifest the contents of Paul’s extraordinary mind, possessing a natural facility to keep to track of all his stock, as well as working out all the prices, discounts for multiples and VAT percentages with ease.

I do not know what I expected when I met Lucinda Rogers for the first time, but I certainly was not prepared for her alluring poise, as she arrived looking chic in a tweed coat with dramatic long straight copper hair, pale skin and a huge ring with a rectangular stone – with an intensity of glamour as if she had stepped from a Jean Luc Godard movie. As we shook hands and I complimented her on her work, she flashed her hazel eyes with a generous smile, and I was momentarily disarmed to realise that she was looking at me with the same shrewd vision which she demonstrates in her elegant work. Once introductions were accomplished, we enjoyed several hours studying this remarkable set of drawings, which exist collectively as a unique portrait of our neighbourhood as it was in the first decade of this new century.

They were created by Lucinda between 2003 and 2008, for an exhibition at the Prince’s Foundation Gallery in Shoreditch and then for a feature in an Italian design magazine, Case da Abitare, as she explained to me, “I was offered an exhibition, so I decided to make it of the East End – because I had only drawn New York up until then – with the focus on Spitalfields and especially on people working. So not really about the buildings, but about recording the things that go on inside the buildings and how they are changing. Not like a photograph, but more about a particular day, your feelings, and what you choose to leave out or leave in to make the picture. You are making something that’s less factual and more subjective.”

The first drawing Lucinda made was of the B2B building in Usborn St at the bottom of Brick Lane. “The reason I did this drawing was because of the numbers that are cut out of plywood and nailed to the wall to advertise the sound studio where the soundtracks for Bollywood films are recorded. The floor beneath is occupied by the rag trade, the Jewish Monumental Mason is next door, in between is the Italian Coffee Shop, while in the background the Gherkin is being built and in the foreground is an apple core.” she told me, enumerating the diverse elements in her picture that coalesce to define the elusive mutable culture of this location, where today an estate agent occupies the property.

The modest aesthetic of these drawings upon tinted paper with just a few touches of colour is dramatically in contrast to their bold compositions and scale. Lucinda’s work is closer to cinema than photography, because confronted with the physical presence of the works you cannot resist turning your head to scan the extent of these images.“I see the finished drawing in my mind,” Lucinda said to me plainly, revealing an imaginative confidence that permits her to work without preparatory drawings, defining the structure of these pictures with her first deftly-placed bold brushstrokes.

Each was completed in a single session on location in the street or in the workplace, contributing to the spontaneity that all these drawings share. The fragile lines that conjure these images out of ether give them tremendous energy and life, whilst also emphasising their diaphanous transient quality of vision. As Lucinda Rogers admitted to me with philosophical smile and a gentle shrug of perplexity, “Everything that I draw changes…”

Paul Gardner at Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen.

Sunday in the Spitalfields Market at Christmas.

Leatherworkers at Hyfact Ltd, Links Yard, Spelman St.

KTP Printing, Princelet St.

Night in the kitchen at the Beigel Bake, looking out towards Brick Lane.

Big John Carter playing Boogie Woogie on Brick Lane.

Saffire furniture shop, Redchurch St.

At the rear of the Nicholls & Clarke building, Norton Folgate.

Columbia Rd Flower Market.

Eugene at North Eastern Motors, Three Colts Lane.

Junction of Middlesex St and Wentworth St, viewed from Petticoat Towers.

Phil at Crown & Leek joinery, Deal St.

B2B Building, Osborn St.

Sunrise wedding services, Hanbury St.

Bishopsgate Goods Yard with Spitalfields and City beyond, viewed from pool deck at Shoreditch House.

Drawings copyright © Lucinda Rogers

Surma Centre Portraits

Spitalfields Life Contributing Photographer Patricia Niven and Novelist Sarah Winman, author of “When God Was a Rabbit,” made this set of portraits at the Surma Centre at Toynbee Hall recently and today it is my pleasure to publish the results of their collaboration.

“After the Second World War, Britain required labour to assist in its post-war reconstruction. Commonwealth countries were targeted and, in what was then East Pakistan (it became Bangladesh after the 1971 Liberation War), vouchers appeared on Post Office counters, urging people to come and work in the United Kingdom, no visa required. The majority of men who came in the 1950’s and 60’s came from a rural background where education was scarce and illiteracy was common. But this generation were hard workers, used to working with their hands, men who could commit to long hours, who had an eagerness to work and a young man’s inquisitiveness to see the world: the perfect workforce to help rebuild this nation. And they did rebuild it, and were soon found working in factories and ship yards, building roads and houses, crossing seas in the merchant navy. These pioneers were the men we met at the Surma Centre.” – Sarah Winman

Shah Mohammed Ali, age 75 years.

I came to this country in November 1961 because my uncle was already living here and inspired me to come. In East Pakistan, I had been working in a shop. I felt life was good. My earliest memory of London was Buckingham Palace. I missed my friends and family but I really missed the weather back home. I became a factory worker, and worked all over the country: a cotton factory in Oldham, a foundry in Sheffield, an aluminium factory in London and Ford motor factory in Dagenham. Ford gave me a good, comfortable life. We had friends all over the country and they would tell us if there was more money being offered at a different factory and then we’d move. I thought I would stay in Britain for four years and then go back home. My heart is in Bangladesh. The roses smell sweeter.

Eyor Miah, age 69 years.

I came to this country in September 1965. I had been a student in East Pakistan. Life was hard, my father was a sailor. I read in a Bengali newspaper stories of people travelling and earning money, and I thought that I, too, would like to do that. I wrote to somebody I knew here to help me. It was a slow process, all done by mail, because of course, there was no internet. It took me two years to gain my papers. I didn’t mind because I was very determined to achieve.

When I first arrived, I became a machinist in the tailoring industry and I earned £1 and ten shillings a week. My weekly outlay was £1 and the rest I saved. Brick Lane was very rundown then. The Jewish population were very welcoming, probably because they were eager for workers! We would queue up outside the mosque and they would come and pick the ones they wanted. In 1969 I bought a house for £55. Of course, I missed my mother who stayed in Bangladesh, and before 1971 I actually thought I would return to live. After that date though, I felt Britain was my home and life was better here.

After tailoring, I worked in restaurants and then began my own business as a travel agent, set up my own restaurants and grocery shop. I have four children. Life has been good to me.

Rokib Ullah, age 81 years.

I came to this country in 1959, because workers were being recruited from the Commonwealth to rebuild after the Second World War. Life in East Pakistan then was good. I was very young and working as a farmer. My fellow countrymen told me about the work in the UK and I came here by air. When I arrived, the airport was so small, not like it is today. And the weather was awful, so bad, not like home, I found that difficult, together with missing my neighbours and friends. I worked in a tyre factory, and then in garment and leather factories. I planned to stay here and earn enough money, and then return to Bangladesh. I am a pensioner now and frequently go back to Bangladesh. It is in my heart. One day I plan to go there forever.

Syed Abdul Kadir, age 77 years.

I first came to this country in 1953. I was in the navy in Karachi and I was selected by the Pakistan Government to be in the Guard of Honour in London at the Queen’s Coronation. I remember this day very clearly. It was June and the weather was cold. When Queen Elizabeth was crowned the noise was tremendous. There were shouts of “God Save the Queen!” and gun salutes were fired. We marched to Buckingham Palace where more crowds were waiting. The Queen and her family came out on the balcony and the RAF flew past the Mall, and the skies above Victoria Embankment were lit up by fireworks. I feel very lucky to have been part of this, and I still have my Coronation ceremony medal.

Since my first visit, I developed a fondness for the British culture, its people and the Royal Family. I have always believed this country looks after its poor.

I owe the Pakistan Navy for much of my experiences in life and was lucky to travel and to see the world. I actively participated in the 1965 India-Pakistan war and the 1971 Pakistan war and have medals for both.

My family are settled here and my life revolves around grandchildren. I have been coming to Surma since 2004. When someone sees me, they call me “Captain!” We are like a family here.

Shunu Miah, age 79 years.

I came to this country in November 1961. Back home, I helped my father farm. It was a good life, still East Pakistan, the population was low, not much poverty, food for everyone: it was a land of plenty. It wasn’t a bad life, I was young and was just looking for more. My uncle had been in the UK since 1931, my father since 1946, both encouraged me to come.

Cinema here was my greatest memory. Back home, cinema was rare. Every Saturday and Sunday there was a cinema above Cafe Naz on Brick Lane, or I’d go to the cinema in Commercial Rd, or up to the West End. It was so exciting, the buildings, the underground, the lights! People were friendly and welcoming then. I saw Indian films, but also Samson and Delilah and the Ten Commandments with Charlton Heston.

I have worked at the Savoy Hotel as a kitchen porter and also in cotton factories in Bradford. What did I miss? Family and friends, of course, but also the weather. The smell of flowers, too, they are much stronger back home. I thought I would stay here and work for three or four years, go home and buy land, build a house and live happily ever after. I have helped to build homes for my family in Bangladesh. I have never been able to own a home here.

Abul Azad, Co-ordinator at the Surma Centre.

“These men are very loyal to a country that has given them a home,” said Abul Azad, the charismatic project co-ordinator at Surma Centre in Whitechapel. “When they first arrived, living conditions were bad, sometimes up to ten people lived in a room. Facilities were unhealthy, toilets outside, and nothing to protect them from an unfamiliar cold that many still talk about. Most intended to earn money to send back to families, and then return after a few years – a dream realised by few, especially after the settlement of families. Instead they were open to exploitation, often working over sixty hours a week, the consequence of which is clearly visible today in low state pensions, due to companies not paying the correct National Insurance contributions. And most Bangladeshi people don’t have private pensions. Culturally, pensions are not of this generation. Their families are their pension – always imagined they would be looked after. But times are changing for everyone.”

Surma runs a regular coffee morning, providing support for elderly Bangladeshi people. The language barrier is still the greatest hindrance to this older generation and Surma provides a specialist team ready to assist their needs – both financially and socially – and to provide free legal advice. It is also quite simply a haven for people to get out of the house and to be amongst their peers, to read newspapers, to have discussions, to talk about what is happening here and in Bangladesh.

There is something profound that holds this group together, a deep unspoken, clothed in dignity. Maybe it is the history of a shared journey, where the desire for a better life meant hours of physical hardship and unceasing toil and lonely years of not being able to communicate. Maybe it is quite simply the longing for home, remaining just that: an unrealised dream. Whatever it is – “This is a very beautiful group.” said Abul Azad.

Photographs copyright © Patricia Niven

You may also like to take look at these other portraits by Patricia Niven and Sarah Winman

An Invitation from The Gentle Author

A Return Visit to Alfred Daniels

Towards the end of my first visit to the studio of Alfred Daniels, the esteemed eighty-six-year-old painter of prolific talent from Bow, he asked me, “Do you think you could come back again next week?” It was an invitation I was happy to accept and – although it took me a little longer than a week – yesterday I travelled eagerly over to Chiswick to pay another call upon him in the large suburban house that his parents bought in 1946 to escape the bombing in the East End.

When I rang the bell twice and received no answer, I peered through the blind into the front room which serves as Alfred’s studio where I spied him, intently at work upon a painting. At first, I was reluctant to disturb his contented reverie but I knew he was expecting me, so I tapped lightly on the window and he sprang into life, coming to the let me in by his front door. Propped up on his desk was a painting of a cat reclining on a fish box with two small boats in the background that Alfred did yesterday. I complimented him on the spirited spontaneous quality of the picture, but he waved my words away with a good-humoured flourish.“It’s the doing of it that’s important not the results,” he informed me with a chuckle, as another thought struck him, “that’s why I gave up religion, because it stops people living in the present tense.”

Yet in spite of his comment, there are certain images that Alfred has returned to continuously throughout his long career and a particular favourite is the gramophone man who always sat in Wentworth St in the nineteen fifties. “I was getting into it,” he admitted in delighted surprise, “and it was becoming different.” The character portrayed in this painting is an East End legend, a subject Alfred first painted from life as a student on a field trip from the Royal College of Art more than sixty years ago. I was intrigued to discover him painting this new version, working from a photograph yet reconfiguring it. “I went there during the blitz, Petticoat Lane and Spitalfields,” he explained to me, thinking out loud again as he resumed work, “it was the first place I experienced a sense of being part of a community, it was the Jewish community then.”

I sat beside Alfred in silence as he grew absorbed in the picture again and cast my eyes around at his other works in progress. Reconsidering themes that resonate for him, he is working on a new depiction of the Royal Exchange in the City and an epic river view looking down the Thames with all the central bridges lined up in parallel. “I never wanted to be a painter,” announced Alfred unexpectedly, still puzzled by the reputation and financial security that his sly, subtly sophisticated paintings have brought him, “I wanted to be an illustrator of life.”

“It isn’t enough to make a picture of something – You have to be there, you have to touch it, you have to experience it.” he assured me as we studied different views of Leadenhall Market that Alfred has done over the years. And he became animated with enthusiasm to revisit the memory of sketching this market more than thirty years ago, an experience distilled further each time he has revisited the image.

Over the phone, Alfred had promised to seek out his Billingsgate sketchbook to show me, that he made in the late sixties when he began drawing on the street as a way to work with art students. “I never tried to teach them, I just took them out with me drawing and worked alongside them so they could see what I did,” he recalled with modest pleasure, pulling the battered hardcover foolscap book from among several in an old satchel on the floor. As Alfred turned the pages, nothing prepared me for the bold fluent quality of his drawings in this book, recording the lost City of half a century ago in crisp confident lines. Alfred’s equal facility with both the human figure and architectural structures creates a tension in these pictures that evokes the energy of the working city with an economy of line which belies the complexity of his vision.

“Did I tell you my story about Francis Bacon?” Alfred asked me, eager again to divert our conversation away from compliments, “He took over from John Minton, teaching us at the Royal College for a spell. In those days, if you were wealthy and well-connected it wasn’t hard to be successful as an artist.” It was an unexpected thought that stopped Alfred in his tracks, as one who possessed none of those prerequisites when he started out. Then, unfortunately, noise at the door terminated our conversation there and I never heard Alfred’s Francis Bacon story, and I never got to look at his stacks of other sketchbooks or hear more of his East End stories. Yet most of all I had enjoyed the peace of sitting with Alfred in his studio while he worked – so this time I was the one to ask the question, “Do you think I could come back again?”

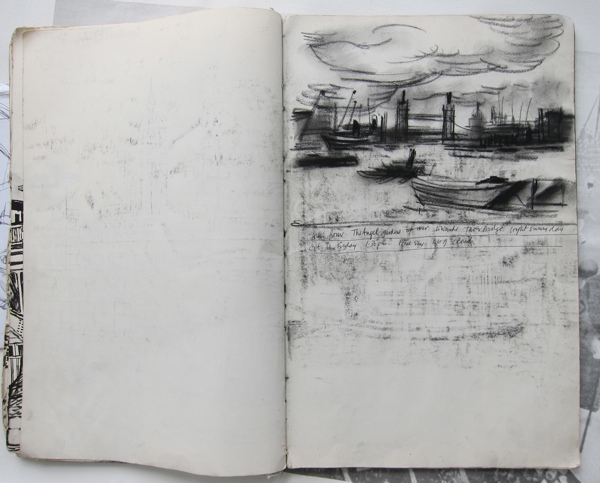

From Alfred’s Billingsgate sketchbook of 1966.

Businessmen at the Royal Exchange and a view of Throgmorton St, 1966.

The old Times building demolished 1968, Upper Thames St.

Southwark Bridge, April 27th

View from the Angel Gardens up river towards Tower Bridge, October 11th Friday 1:30pm

Thameside people, October 1967

Thameside people, dockers, fish porters etc, October 1967

People on London Bridge.

Alfred Daniels

Alfred is exhibiting in The Royal Society of British Artists Annual Exhibition at the Mall Galleries SW1, 29th February – 1oth March. On Wednesday 29th February 11:30am, he will be giving a talk in conjunction with Nick Tidnam on Sketchbooks and Drawing. On Wednesday 7th March 11:30am, he will giving another talk in conjunction with Nick Tidnam, on Arcylics and Mixed Media.

You may like to read about my original visit to Alfred Daniels, Painter