Charles Jones, Gardener & Photographer

Garden scene with photographer’s cloth backdrop c.1900

These beautiful photographs are all that exist to speak of the life of Charles Jones. Very little is known of the events and tenor of his existence, and even the survival of these pictures was left to chance, but now they ensure him posthumous status as one of the great plant photographers. When he died in Lincolnshire in 1959, aged 92, without claiming his pension for many years and in a house without running water or electricity, almost no-one was aware that he was a photographer. And he would be completely forgotten now, if not for the fortuitous discovery made twenty-two years later at Bermondsey Market, of a box of hundreds of his golden-toned gelatin silver prints made from glass plate negatives.

Born in 1866 in Wolverhampton, Jones was an exceptionally gifted professional gardener who worked upon several private estates, most notably Ote Hall near Burgess Hill in Sussex, where his talent received the attention of The Gardener’s Chronicle of 20th September 1905.

“The present gardener, Charles Jones, has had a large share in the modelling of the gardens as they now appear, for on all sides can be seen evidence of his work in the making of flowerbeds and borders and in the planting of fruit trees. Mr Jones is quite an enthusiastic fruit grower and his delight in his well-trained trees was readily apparent…. The lack of extensive glasshouses is no deterrent to Mr Jones in producing supplies of choice fruit and flowers… By the help of wind screens, he has converted warm nooks into suitable places for the growing of tender subjects and with the aid of a few unheated frames produces a goodly supply. Thus is the resourcefulness of the ingenious gardener who has not an unlimited supply of the best appurtenances seen.”

The mystery is how Jones produced such a huge body of photography and developed his distinctive aesthetic in complete isolation. The quality of the prints and notation suggests that he regarded himself as a serious photographer although there is no evidence that he ever published or exhibited his work. A sole advert in Popular Gardening exists offering to photograph people’s gardens for half a crown, suggesting wider ambitions, yet whether anyone took him up on the offer we do not know. Jones’ grandchildren recall that, in old age, he used his own glass plates as cloches to protect his seedlings against frost – which may explain why no negatives have survived.

There is a spare quality and an uncluttered aesthetic in Jones’ images that permits them to appear contemporary a hundred years after they were taken, while the intense focus upon the minutiae of these specimens reveals both Jones’ close knowledge of his own produce and his pride as a gardener in recording his creations. Charles Jones’ sensibility, delighting in the bounty of nature and the beauty of plant forms, and fascinated with variance in growth, is one that any gardener or cook will appreciate.

Swede Green Top

Bean Runner

Stokesia Cyanea

Turnip Green Globe

Bean Longpod

Potato Midlothian Early

Pea Rival

Onion Brown Globe

Cucumber Ridge

Mangold Yellow Globe

Bean (Dwarf) Ne Plus Ultra

Mangold Red Tankard

Seedpods on the head of a Standard Rose

Ornamental Gourd

Bean Runner

Apple Gateshead Codlin

Captain Hayward

Larry’s Perfection

Pear Beurré Diel

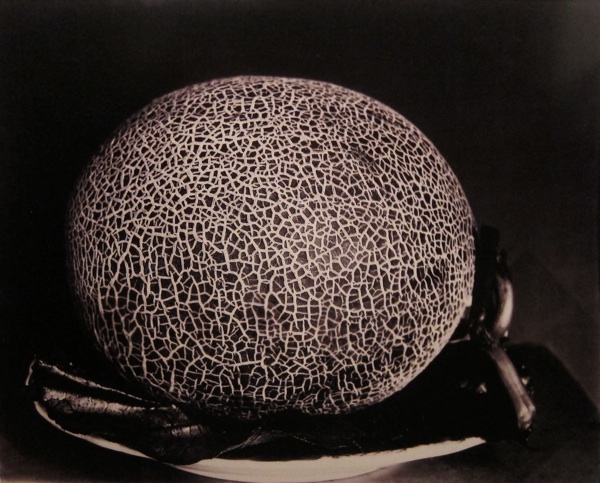

Melon Sutton’s Superlative

Mangold Green Top

Charles Harry Jones (1866-1959) c. 1904

The Plant Kingdom of Charles Jones by Sean Sexton & Robert Flynn Johnson available here

You might also like to read about

The Secret Gardens of Spitalfields

Thomas Fairchild, Gardener of Hoxton

Buying Vegetables for Leila’s Shop

Jocasta Innes, Writer, Cook & Paint Specialist

Even before I met her, Jocasta Innes had been part of my life. I shall never forget the moment in my childhood, shortly after my father lost his job, when my mother came home with a copy of “The Pauper’s Cookbook” by Jocasta Innes, engendering a sinking feeling as I contemplated the earthenware casserole upon the cover – which conjured a Dickensian vision of life sustained upon gruel. Yet the irony was that this book, now a classic of its kind, contains a lively variety of recipes which although frugal in ingredients are far from mundane.

Imagine my surprise when I went round to Jocasta’s kitchen in the magnificent hidden eighteenth century house in Spitalfields where she has lived since 1979 and there was the same pot upon the draining board in her kitchen. I opened the lid in wonder, fascinated to come upon this humble object after all these years – an image I have carried in my mind for half a lifetime and now an icon of twentieth century culture. It was full of a tomato sauce, not so different from photograph upon the famous book cover. Here was evidence – if it should ever be needed – that Jocasta has remained consistent to her belief in the beauty of modest resourcefulness, just as the world has recognised that her thrifty philosophy of make-do-and-mend is not just economic in straightened times but also allows people the opportunity to take creative possession of their personal environment – as well as being a responsible use of limited resources.

“That was the one that made me famous,'” Jocasta admitted to me as we sat down at her scrubbed kitchen table with a copy of “The Pauper’s Cook Book,” “I continually meet people who say, ‘I had that book when I was a student and left home to live on my own for the first time.'” And then, contemplating the trusty hand-turned casserole, she confided, “A lot of people didn’t like the slug of gravy running down the side on the cover.”

Yet “The Pauper’s Cookbook,” was just the beginning for Jocasta. It became one of a string of successful titles upon cookery and interior design – especially paint effects – that came to define the era and which created a business empire of paint ranges and shops at one point. Today, Jocasta still lives in the house that she used to try out her ideas, where you can find almost every paint effect illustrated, and where I visited her to learn the story of this resourceful woman who made a career out of encouraging resourcefulness in others.

“It all started when I was living in this tiny backstreet cottage in Swanage which was only fourteen foot six inches wide and I wanted to give it a bit of style. I got a book of American Folk Art from the library and plundered it for designs, cutting my own stencils out of cereal boxes. And I did a design on the walls of my little girls’ bedroom with tulips up the walls, it was so incredibly pretty.

I thought my parents had unbelievably bad taste, although I realise now it was part of the taste of their time. They loved the colours of rust and brown which I loathe but what captured my imagination was that they had some beautiful Chinese things. My father worked for Shell in China and I was born in Nanjing, one of four children. It was very lonely in a way. There were only about a dozen other children who weren’t Chinese and there wasn’t much mixing in those days. My mother taught eight to ten of us in a dame’s school with an age range of eight to thirteen. I don’t know how she did it. We had exams and there was a lot of rivalry, because if your younger sister did better than you it was pretty painful. She was a Girton Girl and must have taught us pretty well because we all went to Cambridge and so did my daughters.

I worked for the Evening Standard for a while but I was very bad journalist because I was too timid. I’ve always lived by writing and because I had done French and Spanish at Girton, I could do translations. I was desperately poor when I left my first husband and lived in Swanage, so I grabbed any translation work I could and I translated five bodice rippers from French to English, about a tedious girl called Caroline. I got so I could do it automatically and, me and my second husband, we lived on that. We just made ends meet.

“The Pauper’s Cookbook” was my first book and I had a lot of fun doing it. I planned it on two and sixpence per person per meal which would now be about 50p. And I followed it with “The Pauper’s Homemaking Book.” My mother did the embroidery and I covered a chair, it was tremendously home made and full of innocent delight in being a bit clever.

Publisher Frances Lincoln thought the chapter on paint effects could become its own book and that was “Paint Magic.” I fell in with some rich relations who had estate painters trained by Colefax & Fowler and I watched them dragging a lilac wall with pale grey and it was riveting. I didn’t know about glazes, my attempts were primitive compared to theirs. One of John Fowler’s young men, Graham Shire, he taught me how to do tortoiseshell effect and when he showed me the finished result, he said, “Magic!” Nobody liked the title at first. We had a book launch at Harrods and I thought it was going to be a handful of hard-up couples who wanted to decorate their bedsits but half the audience were rich American ladies who had flown over specially and we sold three hundred copies, pretty good for a book about paint.

I was offered a job by Cosmopolitan as Cookery and Design Editor. It was the only time I earned what I would call big money and I sent my girls to college and put my youngest daughter through Westminster School. Once I turned my back on it, I found all the debutantes in London were learning paint finishes and starting little colleges to teach it, and the bottom fell out of the paint finish market. A friend showed me a book called “Shaker Style” and I thought, ‘The writing’s on the wall.”

When I sold the house in Swanage and came to London in 1979, I only had a small amount of money. I was a single parent and my children were six and four. Friends told me to look for a house at the end of the tube lines. But I came on a tour around Spitalfields and Douglas Blaine of the Spitalfields Trust said to me, sotto voce, “I think this one might interest you.” It was part of a derelict brewing complex and the windows were covered with corrugated iron. I climbed onto the roof of what is now my larder and got in through an upper window, I prised apart the corrugated iron to let in the light and saw the room was waist deep in old televisions, mattresses, fridges and cookers. Later, I pulled up five layers of lino with bottletops between them that nobody had bothered to remove. It was tremendously mad, but fun and exciting. I said to Douglas, “I’m up for this!”

I’ve always been a gifted amateur and I think I do best in adversity.”

The Pauper’s Cookbook, first published 1971.

Jocasta’s casserole is an icon of twentieth century culture.

“The Pauper’s Cookbook” made me famous but I am more fond of my “Country Kitchen.”

Jocasta shows you how to do it yourself in her Spitalfields house in the nineteen eighties.

Portrait of Jocasta Innes © Lucinda Douglas-Menzies

At London Trimmings

Moosa, Ashraf & Ebrahim Loonat

If you ever wondered where the Pearly Kings & Queens get the pearl buttons for their magnificent outfits, I can disclose that London Trimmings – the celebrated family business run by the three Loonat brothers in the Cambridge Heath Rd – is the place they favour. And with good reason, as I discovered when I went round to investigate yesterday, because this shop has a mind-boggling selection of wonderful stuff at competitive prices.

Zips and buttons and buckles and threads and tapes and ribbons and snap fasteners and elastic and eyelets and cords and braids and marking chalk and pins, and a whole lot of other coloured and sparkly things, comprise the biggest magpie’s nest on the planet. Now I shall no longer go to fancy West End stores to buy taffeta ribbon to tie up my gifts and pay several pounds for just a couple of metres – not since I discovered that here in Whitechapel you can get a whole reel for five quid and choose from every colour of the rainbow too.

With his lively dark brown eyes and personable nature, Moosa Loonat was my expert guide to this haberdashery labyrinth. He took me on a tour starting in the trade orders department which occupies one of London Trimmings’ two premises in this fine red brick nineteenth century terrace of shops, built by the brewery that once stood across the road. Translucent glass windows might discourage the casual customer, but in fact everyone is welcome in this extraordinary store which feels more like a warehouse than a shop.

Once we had trawled through the crowded aisles here and in the basement, with Moosa pulling out all imaginable kinds of zips and buckles and toggles to explain the stories behind each and every one, he assured me with a proprietorial grin, “I know where everything is, because if you pay for it you know.” I surmise that Moosa said this because while everything has its place at London Trimmings, the overall effect might be described as organised chaos of the most charismatic kind.

Yet, as we explored, Moosa told me the story of the business and I learned there was even more going on here than you can see on the crowded shelves of this extraordinary emporium.

“The shop was started by my father Yousuf Loonat and his partner Aziz Matcheswala in 1971 at the corner of Whitechapel High St and New Rd. My dad came to this country from Gujurat just after the war. He went to Bradford where all the mills were and he worked his way down to Leicester, and from Leicester to London. He told me, at first, he worked in a factory manufacturing street lights and, in Leicester, he went into the food trade and then he got into the textile trade.

At eight years old, I used to go and help count out buttons for my father. Every single holiday, he’d say, “I’ve got lots of work for you.” In 1987, when I was seventeen years old, my father and his partner split, so he gave me a choice – “Either go to university or join the family business – but if you don’t, I’ll sell it.” I took the opportunity and I’m happy that I did. That choice was offered to my brothers too and we realised that if we didn’t all club together, we would lose it. Now every brother runs a different department.

In 1985, we had a fire and lost everything – a couple of hundred thousand pounds of stock and we only had thirty thousand pounds insurance. It was an arson attack. I remember it clearly, it was a dramatic time for the family and my dad was really upset. All our suppliers helped us, they put a freeze on what we owed them until we could repay it and allowed us a new credit account. They contributed to fitting out this new shop in the Cambridge Heath Rd too, they even paid for the sign.

It was busy in the old days, everything was sold by the box then, we had four or five vans in the road and we wouldn’t even entertain student customers. Fifteen years ago, every shop in Brick Lane had a factory above it. In this immediate neighbourhood, we had a thousand customers, now we have a hundred here. We supply the leather trade, the bag trade, the garment trade, the jacket trade, the dry-cleaning and alteration trade, and the shoe repair trade. We cater to students who buy one button and to designers like Mulberry, Hussein Chayalan, Vivienne Westwood and Alexander McQueen, and to High St stores like Top Man and River Island. During London Fashion Week, we had forty people in the shop all wanting to be served first.

Our main speciality is zips, you can buy one for 5p up to £20. We have two hundred different styles and each comes in several sizes. Other suppliers only stock up to No 5, but we have No 6, No 7, No 8, No 9, and No 10 -we even have No 4. We have double-ended zips, fluorescent zips, invisible zips, plastic zips, pocket zips, copper zips, aluminium zips, steel zips, nickel zips, satin zips and waterproof zips.

One customer comes from Ireland, an eighty-five year old man, he comes over every month with a suitcase, packs it up and is gone. Another customer comes regularly from Iceland, she spends two days in here to see what’s new. We had one tailor, he sent back an empty box of 1,044 pins he bought twenty-five years previously, saying “I’d like another one but this is the last I will need because I am over seventy.” Sometimes, people ring from New Zealand to buy press fasteners for the covers on on open-top vintage cars. Kanye West came in twice before we recognised who he was, he came in four or five times altogether, choosing trimmings. He spent a couple of hours each time and had a cup of tea.

I arrive at eight-thirty and I work until seven each day. I do an eleven hour shift. I could choose not to come because I’ve got the staff, but I’m a workaholic. We don’t open at weekends but I still come in on Saturdays to catch up. One day I could be serving customers at the counter, the next day unloading a container and the next out on the road to visit customers. It’s never the same. It’s not a mundane, everything the same, day-in-day-out job. We’ve had my father, me and my nephews all in here at once – three generations working in the same place. Some of the staff have been here thirty years and all the youngsters who came to work here straight from school have stayed.

We run a tight ship financially. The last to get paid will be me and my brothers. We only get our wages if the money’s there but if it’s not, we don’t take it.”

Moosa Loonat – “The last to get paid will be me and my brothers. We only get our wages if the money’s there but if it’s not, we don’t take it.”

Teresa Brace, Manager of Haberdashery – “It’s a lot tidier on my side of the shop!”

Moosa – “As you can see, we’re short of space…”

Ebrahim Loonat

Shirley Mayhew, Accounts Department – in the trimmings business since 1980.

“the biggest magpie’s nest on the planet”

London Trimmings, 26-28 Cambridge Heath Rd, London E1 5QH. 02077902233

Mickey Davis at the Fruit & Wool Exchange

On the day Tower Hamlets Council meet to discuss the redevelopment proposals for the London Fruit & Wool Exchange in Spitalfields, it is my pleasure to publish this memoir by Mike Brooke recalling his uncle Mickey Davis – affectionately known as “Mickey the Midget” – who became a popular hero when he took the initiative to organise the shelter in the basement of the Exchange where as many ten thousand people took refuge nightly, escaping the London Blitz.

Mickey Davis & his wife Doris in the shelter beneath the Fruit & Wool Exchange, 1941

The last time I saw Mickey Davis I was as tall as him – and I was only seven or eight, back then in the Spitalfields of the early nineteen fifties. He came to my school, Robert Montefiore Primary in Deal St, as guest of honour for our annual prize giving. I recognised him in the corridor as we left the assembly hall afterwards, standing against the wall watching us return to our classrooms. I was the proudest kid on the block – because the guest of honour was my Uncle Mickey.

He was, I recall, Deputy Mayor of Stepney (the old Metropolitan borough that later became absorbed into what we now call Tower Hamlets), a very short man, a midget through an accident at birth or defect, I’m not sure exactly. But Mickey was a giant of a man to the community he served in those post-war years and a “people’s hero” of the London Blitz of 1940, several years before I was even born, as I discovered as a journalist working in the East End more than half-a-century later.

I must have been about eight when I roller-skated through the streets of Spitalfields one afternoon and found myself in Fournier St and decided to pop in to see aunt Doris and husband Mickey who lived in a large flat on the first floor of 103 Commercial St, part of the London Fruit & Wool Exchange opposite Spitalfields Church (now known as Christ Church). The kitchen overlooked the indoor wholesale trading area and there was always a faint smell of fruit and veg in the background, while the front room overlooked Commercial St, roughly level with the overhead wires of the 647 and 665 trolleybuses. It seemed quite a posh apartment to an eight-year-old.

But I didn’t go inside that afternoon. My grandmother, aunt Doris and my late father Henry’s mother, answered the door and told me immediately that uncle Mickey was dead. It was an abrupt manner to an eight-year-old, but I knew she was upset. I left and skated straight home to Granby St, along Brick Lane, rushing to tell my mother. She had not heard about Mickey yet, but knew he had been in hospital. We did not have a phone in the house in those days.

Doris and my mother Connie had been great friends during the War and worked together. It was through Doris that my mother and father met when he came home on leave from the Royal Navy in 1943. He visited his sister at work and took a fancy to Connie. They married while he was on leave and he was recalled back to Plymouth to rejoin his ship on their wedding night, so my mother once told me.

My mother immediately put a coat on and went over to see Doris that day in 1954 when I told her about the death of Uncle Mickey. It was not until decades later that I learned the full story of Mickey Davis – and how he organised a shelter committee during the early days of the Blitz at the Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange – when the BBC contacted my family in the nineteen eighties, researching a possible documentary, though I do not think the programme was ever made. It was another two decades before I did my own research for an article about Mickey Davis for a commemorative supplement in the East London Advertiser, where I was Features Editor, marking the seventieth anniversary of the start of the Blitz in September 2010,.

Mickey, who at three feet three inches tall was known as ‘”the Midget,” was an East End optician who threw his energies into organising and improving shelter life, I wrote. He had emerged as the unofficial leader who pushed for improvements to health and safety in one of the East End’s biggest air raid shelters at the Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange in Brushfield St. While the local authority, Stepney Borough Council, was concerned by the 2,500 people crammed into the shelter each night, with its lack of sanitation, risking disease and infection, and lack of facilities for food, lighting and heating, it was left to Mickey set up first aid and medical units, and raise money to equip a dispensary. He even persuaded stretcher bearers and others to come in on their off duty times to minister to the sick and injured. As a popular activist and orator, he became indispensable to the people, pushing the authorities into action.

Long before medical posts became the official practice, well-to-do friends of Mickey provided his Spitalfields public shelter with drugs and equipment. A GP friend made two-hour journeys each day to the East End to spend his nights among the poor. Eight years before the NHS was set up, Mickey’s shelter in 1940 had a free medical service already up-and-running. He even devised a card index system of everyone who used the shelter, and introduced hygiene practices and protection against disease. He persuaded Marks & Spencer to donate money for a canteen and used the profits to provide free milk for children. When the wartime Government eventually appointed official shelter marshals, Mickey was replaced – but the first action of the Spitalfields Shelter Committee undertook was to vote him to be Shelter Marshal, responsible for 2,500 people.

His thinking in 1940 was a fore-runner of the post-war Welfare State that emerged in 1948. He was a man known affectionately among East Enders as “the midget with the heart of a giant.”That was the Mickey Davis, who I am proud to have called “uncle.”

Mickey Davis, popularly known as “Mickey the Midget,” who became a hero of the London Blitz – photo by Bert Hardy

Mickey (in the foreground) convenes a planning meeting in the basement of the Fruit & Wool Exchange in 1941 – photo by Bert Hardy

Musical entertainment for people sleeping in “Mickey’s Shelter” in the Fruit & Wool Exchange.

The space of “Mickey’s Shelter” unchanged today.

Graffiti remaining from the days of the shelter in the basement of the Fruit & Wool Exchange.

The Fruit & Wool Exchange today.

The Auction room at the Fruit & Wool Exchange in the nineteen thirties.

Bert Hardy photographs © Getty Images

Photo of Auction Room courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

The Book Launch at Christ Church

As I left the house at quarter to seven and made my way through the dark foggy streets towards Christ Church, the bells began to ring. Turning the corner from Princelet St into Wilkes St, I met Stanley Rondeau the Huguenot – whose ancestor Jean Rondeau came to Spitalfields in 1685. Stanley was lingering outside number four where his forbears’ house once stood. “The bells are ringing for us,” I said to him and he gave me a sympathetic nod of recognition as we shook hands, before walking onwards to the church together.

Coming round into Commercial St, I had the biggest surprise of my life to witness hundreds of excited people gathering to be admitted into the church. With the clamour of bells echoing in my head, I climbed the steps quickly and made my way through the crowd to the door. “They’re not opening it until seven,” I was told by an authoritative bystander, causing me to break into a sweat, and so I hammered on the door. Thankfully, speaking the magic words, “I am the author,” assured my admission.

Once inside, I was greeted by my oldest friend from college days, now a teacher in Somerset, who had let her class go home early in order to get a train from Taunton and be in Spitalfields by seven o’clock. She brought me a bunch of primroses picked in a lane near Wiveliscombe that morning and we sat quietly in a corner, immediately absorbed in exchanging news.

Then the doors opened and great surge of people led by a contingent of magnificently attired Pearly Kings & Queens came into the church filling the nave and side aisles – a wonderful vision to see so many of those I have written about, all together in one place consuming Eccles cakes and beer. At once, readers were recognising those they knew from my stories and I saw many spontaneous introductions which ignited the party, firing up the social event at the core of the evening, as hundreds of people who had never met before entered into lively conversations with each other. It was the party of the year in Spitalfields. A night that will be discussed in The Golden Heart for months to come. I could have stood and watched the spectacle of it all evening. I could have spent all evening talking to all the friends that I made through my interviews – but it was not to be.

I sat down at a table and, even without announcing myself, I was handed a book to sign and then another and another. In fact, I signed three hundred in an hour and a half, concentrating my mind upon the practical task of maintaining the quality of my handwriting and spelling everyone’s name correctly. Yet most touching were the moments of connection as I shook hands or made eye contact with readers who had so graciously come to meet me. What an extraordinary, unforgettable moment of mutual recognition it was when we got to see each other at last, meeting in the temporal world. Now I know who I am writing to.

Rodney Archer, the Aesthete, escorts Sandra Esqulant, the Queen of Spitalfields.

Leila’s Cafe served the Eccles Cakes from St John with slices of Lancashire Cheese.

Truman’s Beer served Truman’s Runner Ale.

Elizabeth Hallet, Editor of Saltyard Books, introduced the book.

Andy Rider, Rector of Christ Church Spitalfields, made a blessing upon the book.

Mark Hearld, Artist, Elizabeth Hallet, Publisher & Angie Lewin, Artist.

Gary Arber, Printer & Flying Ace, with two admirers.

Stephen & Clive Phythian, Tailors from Alexander Boyd.

Nevio Pellici & Fiancée.

Matthew Reynolds of the Duke of Uke introduces the Ukelele Orchestra.

The Ukelele Orchestra played “Troubles are like bubbles.”

King Sour, Rapper of Bethnal Green.

Pearly Kings & Queens.

Captain Shiv Banerjee, Justice of the Peace.

Paul Gardner, Paper Bag Seller, autographs books for fans.

Jason Hart, WordPress Wizard, & Rob Ryan, Artist & Papercut Supremo.

Novelist Sarah Winman & stylish friend.

Mavis Bullwinkle & photographer friend.

Jodie Krestin & Pamela Freedman, formerly of The Princess Alice in Commercial St.

Paul Gardner, Market Sundriesman & Jo Waterhouse, Antiques Market Trader.

Nick Appleton, Animator & Paul Bommer, Artist.

Boudicca & admirers.

King Sour & his crew.

Paul Bommer, Artist, Kitty Valentine, Artist & Leo, Artist.

Carrom Paul, Proprietor of the Carrom Shop, supplied Carrom Boards.

Nikki Cleovoulou, Pamela Freedman & Renee Cleovoulou.

At one point the line stretched round to St John in Commercial St.

[youtube u2ej3o_ET2I nolink]

Photographs by Sarah Ainslie & Jeremy Freedman,

additional images by Alex Pink & Amy Smith

Film by Sebastian Sharples

Charles Goss’ Photographs

Borer’s Passage, entrance to Old Clothes Market, 16th July 1911

Stefan Dickers, Archivist at the Bishopsgate Institute was looking through a box of uncatalogued photographs recently when he recognised the handwriting of his predecessor, Charles Frederick William Goss – the first Archivist at the Institute, from 1897 -1941 – and he realised he had discovered a set of around fifty pictures taken one hundred years ago to record the streets in the immediate vicinity. Unseen for many decades, it is my privilege to publish the first ever selection from these fascinating photographs today.

It is not known if Goss took these photographs or if he commissioned then, yet his inscription upon the reverse of “Railway Tavern, London St. Taken 8th October, 1911. Printed 1st December, 1911. Demolished 1911.” suggests that he was the photographer. The son of a plasterer and of the first generation of his family to be literate, Goss built the foundation of the archive as his life-long vocation and later wrote, “The years I spent at Bishopsgate were the happiest years of my life.” And today, Stefan Dickers talks fondly of William Goss as if he were a personal friend, because Goss’ presence – signified by his careful copperplate handwriting – is everywhere in the archive.

Compared to the photographs by Henry Dixon by for the Society for the Photographing the Relics of Old London, taken in the eighteen eighties, which mostly show buildings straight-on and in which the people are incidental, many of Goss’ photographs possess a more apparent subjectivity. The nature of the set of the pictures manifests the purpose of recording the streets as they were in Goss’ time, but there is also a poetic sensibility at work that seeks to contrive artistic compositions and in which the presence of people is integral to the pictures.

In “Savage Gardens, east side, 5th June 1911” a boy is caught in the very moment of swinging a cricket bat. He is the only living thing in a picture filled by the architectural grid of the terrace behind him, and his presence reveals the tension – between recording the buildings and the fleeting drama of human life that passes before the lens – which characterise Goss’ pictures. Equally intriguing is “Doorway, 3 Fenchurch Buildings, 28th October 1911” in which a man stands in the shadow just within the door. The photographer could have asked this man to move or waited until he had gone, yet he chose to include him and by doing so he transforms what might be a routine architectural record into a compelling image of permanent enigma. The girl in the hat standing in “1 Savage Gardens, Aldgate, 5th June 1911” proposes another unknowable drama. The key element in the composition of the photograph, her presence invites speculation that cannot be resolved.

Goss’ abiding concern, reflecting his own family background, is manifest in the vast London collection at the Bishopsgate with its strong emphasis upon the lives of working people. A concern illustrated sympathetically in “Borer’s Passage, entrance to Old Clothes Market, 16th July 1911,” in which people become the central subject of the photograph, taking precedence over the buildings. This is an image that is closer to street photography than architectural documentation.

Goss’ curious pictures reveal something of the essential nature of photography as a medium premised upon the capture of the ephemeral moment. My own experience has taught me that setting out to make a photographic record of the present day sets you apart, even as you are in the thick of the crowd, and makes you more vividly aware of the transience of the drama of life surrounding you, imbuing the everyday with an irresistible poignancy. And, from the evidence of this set, I suggest that whoever took these photographs felt that emotion too.

Leadenhall St from Saracen’s Head, Aldgate, looking west, 16th July 1911

Phil’s Buildings, Houndsitch, 16th July 1911 – London’s largest second hand clothes market

Doorway, 3 Fenchurch Buildings, 28th October 1911

Love Lane, looking south, church of St Mary at Hill, 18th September 1911

7 Love Lane, Billingsgate Ward, 16th December 1911

Fish St Hill from Lower Thames St, 28th January 1912

1 Savage Gardens, Aldgate, 5th June 1911

Catherine Wheel Alley, Spitalfields, looking north

Savage Gardens, east side, 5th June 1911

Wrestlers Court, Bishopsgate, 1910

Railway Tavern, London St. Taken 8th October, 1911. Printed 1st December, 1911. Demolished 1911.

Charles Frederick William Goss (1864-1946), first Archivist at the Bishopsgate Institute

Photographs courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to look at the photographs of The Society for Photographing the Relics of Old London

In Search of the Relics of Old London

or the photographs of C.A.Mathew

In the footsteps of C.A.Mathew

or

Remembering the Camp at St Pauls

In the week that the City of London evicted the camp from St Paul’s Cathedral, it is salient to recall the moment of joy in October when it all started – upon the spot that is both where campaigners gathered to demand the Magna Carta in 1215 and where the Gunpowder plotters were executed in 1606.

Something extraordinary has happened at St Paul’s Cathedral. Inspired by the recent occupation of Wall St in New York, protestors gathered in the City of London to occupy the Royal Exchange on Saturday, yet the police made sure they never got beyond their rallying point on the steps of the Cathedral. But then – in an unexpected move – Canon Giles Fraser came out of St Paul’s to welcome them and ask the police to leave, effectively granting sanctuary to the protestors. And since Saturday, they have pitched a small encampment of tents beneath the towering West front of Wren’s great edifice, thus establishing a highly visible presence for themselves at the heart of Europe’s financial centre, with the blessing of the Cathedral authority.

In just a few days, this city within the City has established its own life, with a first aid post, legal advice centre, a cafeteria serving meals prepared from donations of food which are being received, a recycling centre and even a university offering seminars in alternative economics and a range of other relevant topics. “We all understand there’s something fundamentally wrong,” one of the tent occupants admitted to to me, citing the prolonged wars, global financial crisis and collapsing economies that are indicative of our time.

“Does the society we live in function to benefit the people who live in it, or for some other reason? – to benefit only the rich? – to benefit those in power?” he asked rhetorically, gesturing to the buildings of the City that surrounded us, “People are losing their homes, their jobs, they cannot pay their bills, and entire countries are going broke – that is why we are here.”

I stood among the sea of tents in the deep shadow of late afternoon with a bright October sky overhead and realised I had arrived in a different place, an intense emotional space, transformed by the presence of those camping there. Everywhere I looked, people were engaging in heated discussions about is right and what is wrong, and what should be done about it. City workers and other passersby had stopped to participate in debates, among the tents, those dwelling there were sitting in circles discussing their beliefs, and upon the steps of the Cathedral large crowds were gathering to participate in disputes filmed by television cameras. “This is not about Left or Right, it’s a human thing,” explained my host, recognising the wonder upon my face in reaction to the spectacle – “something needs to change.”

Yet to my eyes, a near miraculous change had already come about – because the presence of the camp gave everyone the opportunity to speak their minds publicly, to be heard and to listen. The combination of circumstances had delivered a rare moment of liberty, in which recognition of common humanity was uppermost as the basis for all interaction.

The quality of openness and mutual respect – and the possibility that complete strangers could open their hearts to share their beliefs about what kind of world they want to live in – was such that I can only describe this event as a spiritual one.

In front of the vast Cathedral, a man was reciting the sermon on the mount. All around, musicians were playing and the standard anonymity of the City streets was suspended. Normality was exposed as a charade because a group of ordinary decent people felt passionate enough to risk themselves, taking leave of their jobs and families and everyday lives, sleeping on concrete at the onset of Winter in Northern Europe to express their moral outrage at the direction our world has taken. And when you see this, it renews your hope.

[youtube 4UbgTgC5nMY nolink]

[youtube OL94wGGoQBQ nolink]

Spitalfields resident Robson Cezar, the King of the Bottletops, who became Artist-in-Residence at Occupy London, seen here on the cover of the Herald Tribune at the time of the National Strike.

Robson Cezar at Finsbury Sq last November.

You may also like to read about