So Long, Jocasta Innes

Jocasta Innes died at home in Spitalfields over the weekend and today I am republishing my profile as a tribute to a talented woman who enriched so many people’s lives through her creative thinking.

Jocasta Innes

Even before I met her, Jocasta Innes had been part of my life. I shall never forget the moment, shortly after my father lost his job, when my mother came home with a copy of “The Pauper’s Cookbook” by Jocasta Innes, engendering a sinking feeling as I contemplated the earthenware casserole upon the cover – which conjured a Dickensian vision of a future sustained upon gruel. Yet the irony was that this book, now a classic of its kind, contained a lively variety of recipes which although frugal were far from mundane.

Imagine my surprise when I went round to Jocasta’s kitchen in the magnificent hidden eighteenth century house in Spitalfields where she had lived since 1979 and there was the same pot upon the draining board. I opened the lid in wonder, fascinated to come upon this humble object after all these years – an image I have carried in my mind for half a lifetime and now an icon of twentieth century culture. It was full of a tomato sauce, not so different from the photograph upon the famous book cover. Here was evidence – if it should ever be needed – that Jocasta had remained consistent to her belief in the beauty of modest resourcefulness, just as the world had recognised that her thrifty philosophy of make-do-and-mend was not merely economic in straightened times but also allowed people the opportunity to take creative possession of their personal environment – as well as being a responsible use of limited resources.

“That was the one that made me famous,'” Jocasta admitted to me when we sat down together at her scrubbed kitchen table with a copy of “The Pauper’s Cook Book,” “I continually meet people who say, ‘I had that book when I was a student and left home to live on my own for the first time.'” And then, contemplating the trusty hand-turned casserole, she confided, “A lot of people didn’t like the slug of gravy running down the side on the cover.”

Yet “The Pauper’s Cookbook,” was just the beginning for Jocasta. It became one of a string of successful titles upon cookery and interior design – especially paint effects – that came to define the era and which created a business empire of paint ranges and shops. Forty years later, Jocasta was still living in the house that she used to try out her ideas, where you could find almost every paint effect illustrated, and where I visited to learn the story of this superlatively resourceful woman who made a career out of encouraging resourcefulness in others.

“It all started when I was living in this tiny backstreet cottage in Swanage which was only fourteen foot six inches wide and I wanted to give it a bit of style. I got a book of American Folk Art from the library and plundered it for designs, cutting my own stencils out of cereal boxes. And I did a design on the walls of my little girls’ bedroom with tulips up the walls, it was so incredibly pretty.

I thought my parents had unbelievably bad taste, although I realise now it was part of the taste of their time. They loved the colours of rust and brown which I loathe but what captured my imagination was that they had some beautiful Chinese things. My father worked for Shell in China and I was born in Nanjing, one of four children. It was very lonely in a way. There were only about a dozen other children who weren’t Chinese and there wasn’t much mixing in those days. My mother taught eight to ten of us in a dame’s school with an age range of eight to thirteen. I don’t know how she did it. We had exams and there was a lot of rivalry, because if your younger sister did better than you it was pretty painful. She was a Girton Girl and must have taught us pretty well because we all went to Cambridge and so did my daughters.

I worked for the Evening Standard for a while but I was very bad journalist because I was too timid. I’ve always lived by writing and because I had done French and Spanish at Girton, I could do translations. I was desperately poor when I left my first husband and lived in Swanage, so I grabbed any translation work I could and I translated five bodice rippers from French to English, about a tedious girl called Caroline. I got so I could do it automatically and, me and my second husband, we lived on that. We just made ends meet.

“The Pauper’s Cookbook” was my first book and I had a lot of fun doing it. I planned it on two and sixpence per person per meal which would now be about 50p. And I followed it with “The Pauper’s Homemaking Book.” My mother did the embroidery and I covered a chair, it was tremendously home made and full of innocent delight in being a bit clever.

Publisher Frances Lincoln thought the chapter on paint effects could become its own book and that was “Paint Magic.” I fell in with some rich relations who had estate painters trained by Colefax & Fowler and I watched them dragging a lilac wall with pale grey and it was riveting. I didn’t know about glazes, my attempts were primitive compared to theirs. One of John Fowler’s young men, Graham Shire, he taught me how to do tortoiseshell effect and when he showed me the finished result, he said, “Magic!” Nobody liked the title at first. We had a book launch at Harrods and I thought it was going to be a handful of hard-up couples who wanted to decorate their bedsits but half the audience were rich American ladies who had flown over specially and we sold three hundred copies, pretty good for a book about paint.

I was offered a job by Cosmopolitan as Cookery and Design Editor. It was the only time I earned what I would call big money and I sent my girls to college and put my youngest daughter through Westminster School. Once I turned my back on it, I found all the debutantes in London were learning paint finishes and starting little colleges to teach it, and the bottom fell out of the paint finish market. A friend showed me a book called “Shaker Style” and I thought, ‘The writing’s on the wall.”

When I sold the house in Swanage and came to London in 1979, I only had a small amount of money. I was a single parent and my children were six and four. Friends told me to look for a house at the end of the tube lines. But I came on a tour around Spitalfields and Douglas Blaine of the Spitalfields Trust said to me, sotto voce, “I think this one might interest you.” It was part of a derelict brewing complex and the windows were covered with corrugated iron. I climbed onto the roof of what is now my larder and got in through an upper window, I prised apart the corrugated iron to let in the light and saw the room was waist deep in old televisions, mattresses, fridges and cookers. Later, I pulled up five layers of lino with bottletops between them that nobody had bothered to remove. It was tremendously mad, but fun and exciting. I said to Douglas, “I’m up for this!”

I’ve always been a gifted amateur and I think I do best in adversity.”

The Pauper’s Cookbook, first published 1971.

Jocasta’s casserole became an icon of twentieth century culture.

“The Pauper’s Cookbook” made me famous but I am more fond of my “Country Kitchen.”

Jocasta showed you how to do it yourself in her Spitalfields house in the nineteen eighties.

Portrait of Jocasta Innes © Lucinda Douglas-Menzies

As part of the recent Huguenots of Spitalfields Festival, there was a service of thanksgiving at Christ Church in which Jolyon Tibbitts, Upper Bailiff of the Worshipful Company of Weavers stood up and read my story A Dress of Spitalfields Silk to the assembled congregation. First recorded in 1130, the Weavers is the oldest livery company in the City of London and so, fascinated by the history of this arcane body, I accepted Jolyon Tibbitts’ invitation to visit him at their headquarters in the Saddlers’ Hall, Gutter Lane, next to St Pauls.

The textile industry was the basis of the country’s economy when the Weavers’ Company began – before the first London Bridge was built in 1176 or the first Mayor took office in 1189, in an era referred to by Medieval writers as “a time whereof the memory of man runneth not to the contrary.” Through their charter, the members paid a sum to the crown in return for certain rights that protected the interests of their industry. In the prologue to the Canterbury Tales, Chaucer writes of “A Haberdasher, a Dyer, a Carpenter, a Weaver and a Carpet-maker were among our ranks, all in the livery of one impressive fraternity.”

The Weavers’ Company sought to shield their members against competition at first from Flemish weavers in the fourteenth century and again, from Huguenot weavers, in the seventeenth century yet, on each occasion, the immigrants became absorbed into the company. Ultimately, more destructive to the industry were cheap imports introduced by the East India Company, reducing the Spitalfields weavers to poverty by the middle of the eighteenth century, although a few continued in Bethnal Green even into the last century.

Jolyon Tibbitts’ ancestors started as scarlet dyers and became silk weavers at least six generations ago in Spitalfields in the sixteenth century, founding Warner & Sons Ltd, and then moving to Braintree in the nineteenth century, where the mill stands today as a textile archive. By the time Jolyon was born, the family business had been sold into American hands, yet he has spent his life involved with textiles and, contradicting the familiar story of the decline of weaving in this country, I was delighted to learn the surprising news from him that for the first time in centuries our native industry is on the rise again.

“In the nineteen sixties, there was a wholesale movement of textile manufacturing from here to the Far East on the back of cheap labour and government subsidies. All that really survived here were the very high end manufacturers in fashion and furnishings. But in the past few years, we have seen a major change. The Far East has experienced inflation both in wages and materials, and government subsidies have ceased plus freight prices have escalated hugely.

Taking into account the monetary cost of the long lead times in the Far East, this situation has encouraged more foresighted buyers to refocus on British manufacturing. We can be price competitive now and the difference between manufacturing here and in the Far East is less significant. Consequently, the British mills are experiencing a true revival in fortune, not just in this country but in world markets, more and more mills are establishing themselves as brands now and selling direct to the customers.

The Weavers, in collaboration with the Clothworkers and the Dyers Companies, staged a conference in the City of London last autumn entitle ‘A New Dawn,’ at which Sir Paul Smith and Vince Cable were our key speakers among other industry leaders. We support an internship programme whereby we pay two-thirds of the salary for able graduates to work with weaving companies for six months. We are very careful in matching the skills of the graduates to the needs of the companies and most of the students end up being offered full-time employment by the company after these placements, and, in recent years, we have been able to double the number of these placements.

We make awards to individuals who have made significant contributions and this year’s winner of the Silver Medal was Donald John MacKay who has revived the Harris Tweed industry by persuading Nike to use it in their shoes, winning an order for more than a million metres, and the resulting media interest created a flow of orders that put the industry back on the map again.

My father was a livery man and uncle was a livery man, and so was my grandfather and great grandfather. I became a livery man after seven years apprenticeship in 1968 and joined the council in 2005. Once, every livery company had an ‘Upper Bailiff’ but they all changed it to ‘Master’ over time yet, through eight hundred years, we have kept the original name.”

Charter of Henry II to the Weavers of London granting them their Guild and protection from interference in their trade, 1155-8. The charter is attested by Thomas Becket. Appended is a fragment of the Great Seal, with casts of the full seal on either side. “Know that I have conceded to the Weavers of London to hold their guild in London with all the liberties and customs which they had in the time of King Henry my grandfather.”

Early seventeenth century portrait of Elizabeth I in the possession of the Weavers Company.

Weavers’ Silver Loving Cup, 1662

Weavers’ Poore’s Box, 1666

Promise to contribute to the rebuilding of the Weavers’ Hall after the Great Fire

Nicholas Garrett Weavers’ Almshouses, Porters’ Fields, 1729

William Watson Weavers’ Almshouses, Shoreditch, 1824

Weavers’ Almshouse Wanstead, 1859

Samuel Higgins, silk weaver, in his loom shop at Gauber St, Spitalfields, 1899

Typical Weaver’s House, Spitalfields, 1825

Badge of the Upper Bailiff of the Weavers’ Company – “Weave Truth With Trust”

Archive images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

Portrait of Jolyon Tibbitts copyright © Jeremy Freedman

You may also like to read about

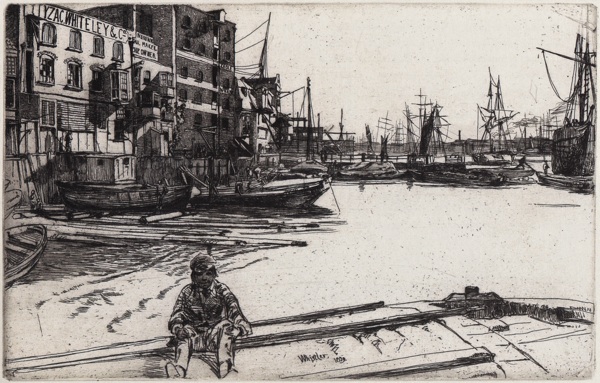

Whistler in Limehouse & Wapping

DMW937351 The Lime-Burner, from “A Series of Sixteen Etchings of Scenes on the Thames”, 1859, printed 1871 (etching & drypoint) by Whistler, James Abbott McNeill (1834-1903); 27.9×20.3 cm; Davis Museum and Cultural Center, Wellesley College, MA, USA; Bequest of George H. Webster; American, out of copyright

W.Jones, Limeburner, Wapping High St

American-born artist, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, was only twenty-five when he arrived in London from Paris in the summer of 1859 and, rejecting the opportunity of staying with his half-sister in Sloane St, he took up lodgings in Wapping instead. Influenced by Charles Baudelaire to pursue subjects from modern life and seek beauty among the working people of the teeming city, Whistler lived among the longshoremen, dockers, watermen and lightermen who inhabited the riverside, frequenting the pubs where they ate and drank.

The revelatory etchings that he created at this time, capturing an entire lost world of ramshackle wooden wharfs, jetties, warehouses, docks and yards, are displayed in a new exhibition which opened this week at the Fine Art Society in New Bond St. Rowing back and forth, the young artist spent weeks in August and September of 1859 upon the Thames capturing the minutiae of the riverside scene within expansive compositions, often featuring distinctive portraits of the men who worked there in the foreground.

The print of the Limeburner’s yard above frames a deep perspective looking from Wapping High St to the Thames, through a sequence of sheds and lean-tos with a light-filled yard between. A man in a cap and waistcoat with lapels stands in the pool of sunshine beside a large sieve while another figure sits in shadow beyond, outlined by the light upon the river. Such an intriguing combination of characters within an authentically-rendered dramatic environment evokes the writing of Charles Dickens, Whistler’s contemporary who shared an equal fascination with this riverside world east of the Tower.

Whistler was to make London his home, living for many years beside the Thames in Chelsea, and the river proved to be an enduring source of inspiration throughout a long career of aesthetic experimentation in painting and print-making. Yet these copper-plate etchings executed during his first months in the city remain my favourites among all his works. Each time I have returned to them over the years, they startle me with their clarity of vision, breathtaking quality of line and keen attention to modest detail.

Limehouse and The Grapes – the curved river frontage can be recognised today.

The Pool of London

Eagle Wharf, Wapping

Billingsgate Market

Longshore Men

Thames Police, Wapping

Black Lion Wharf, Wapping

Looking towards Wapping from the Angel Inn, Bermondsey

‘Whistler on the Thames’ is at the Fine Art Society, 148 New Bond St until 9th May

You may also like to read about

Dickens in Shadwell & Limehouse

Madge Darby, Historian of Wapping

Samuel Pepys in Spitalfields, 1669

Contributing Artist Paul Bommer sent me this sly drawing, envisaging Samuel Pepys’ visit to Spitalfields, three hundred and forty-four years ago today.

Up and to the Office, and my wife abroad with Mary Batelier, with our own coach, but borrowed Sir J Minnes’s coachman, that so our own might stay at home, to attend at dinner – our family being mightily disordered by our little boy’s falling sick the last night, and we fear it will prove the small-pox.

At noon comes my guest, Mr Hugh May, and with him Sir Henry Capell, my old Lord Capel’s son, and Mr. Parker, and I had a pretty dinner for them, and both before and after dinner had excellent discourse, and shewed them my closet and my Office, and the method of it to their great content, and more extraordinary, manly discourse and opportunity of shewing myself, and learning from others, I have not, in ordinary discourse, had in my life, they being all persons of worth, but especially Sir H. Capell, whose being a Parliament-man, and hearing my discourse in the Parliament-house, hath, as May tells me, given him along desire to know and discourse with me.

In the afternoon, we walked to the Old Artillery-Ground near the Spitalfields, where I never was before, but now, by Captain Deane’s invitation, did go to see his new gun tryed, this being the place where the Officers of the Ordnance do try all their great guns, and when we come, did find that the trial had been made – and they going away with extraordinary report of the proof of his gun, which, from the shortness and bigness, they do call Punchinello. But I desired Colonel Legg to stay and give us a sight of her performance, which he did, and there, in short, against a gun more than twice as long and as heavy again, and charged with as much powder again, she carried the same bullet as strong to the mark, and nearer and above the mark at a point blank than theirs, and is more easily managed, and recoyles no more than that, which is a thing so extraordinary as to be admired for the happiness of his invention, and to the great regret of the old Gunners and Officers of the Ordnance that were there, only Colonel Legg did do her much right in his report of her.

And so, having seen this great and first experiment, we all parted, I seeing my guests into a hackney coach, and myself, with Captain Deane, taking a hackney coach, did go out towards Bow, and went as far as Stratford, and all the way talking of this invention, and he offering me a third of the profit of the invention, which, for aught I know, or do at present think, may prove matter considerable to us – for either the King will give him a reward for it, if he keeps it to himself, or he will give us a patent to make our profit of it – and no doubt but it will be of profit to merchantmen and others, to have guns of the same force at half the charge.

This was our talk – and then to talk of other things, of the Navy in general and, among other things, he did tell me that he do hear how the Duke of Buckingham hath a spite at me, which I knew before, but value it not: and he tells me that Sir T. Allen is not my friend, but for all this I am not much troubled, for I know myself so usefull that, as I believe, they will not part with me; so I thank God my condition is such that I can retire, and be able to live with comfort, though not with abundance.

Thus we spent the evening with extraordinary good discourse, to my great content, and so home to the Office, and there did some business, and then home, where my wife do come home, and I vexed at her staying out so late, but she tells me that she hath been at home with M. Batelier a good while, so I made nothing of it, but to supper and to bed.

Tuesday 20th April, 1669

Illustration copyright © Paul Bommer

Paul Bommer’s work can be seen at Pick Me Up Somerset House, from today until 28th April.

You may also like to take a look at

Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary

Elizabeth Crawford, bookdealer and writer specialising in the Women’s Suffrage Movement, reveals how she discovered Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary, telling the forgotten story of one woman’s contribution to the campaign for Votes for Women which took place in the East End a century ago.

Kate Parry Frye (1878-1959)

Operating from 321 Roman Rd, Sylvia Pankhurst’s ‘East London Federation of Suffragettes’ is the most famous of the groups in the East End who backed George Lansbury, the Labour MP, when he resigned his Bromley & Bow seat to fight a by-election on the ‘Votes for Women’ issue in the autumn of 1912. Yet, also knocking on doors and holding meetings was the ‘New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage’ about which very little was known, until now.

In 1912, the diarist, Kate Parry Frye, was out on the streets of Bow canvassing for Lansbury and she also took part in a short, sharp Whitechapel campaign, a year later. Her voluminous diary has only recently come to light, replete with an archive of associated ephemera, recording her efforts to convert the men and women of Southern England to the cause of ‘Votes for Women.’ Her diary entries, written while she was a paid organiser for the Society, bring to life what was – in her eyes – the alien territory of the East End.

I discovered the diaries piled in boxes in a dripping North London cellar while working in my capacity as book dealer. Loath to reject this record of one woman’s entire life, however unsellable the soaking volumes appeared, curiosity got the better of my common sense and I purchased them. Once they were dried out, I began to read them and the existence of the diarist took shape – or, rather, Kate reshaped herself as she came to life.

Her story is not extraordinary in outline, but extraordinary in the engrossing details of life that she committed to paper. Where another diarist might select only the highlight of a day, Kate gives us train times, meal times, details of the contents of those meals, details of lodgings, landladies, restaurants, tube lines, parties, palm readings, clothes-buying, dog-walking, dentist and doctor visits, attendance at election meetings, Suffrage campaigning – both as a volunteer and as an employee – and of play-going and play-writing.

Kate, a well brought-up daughter of the ‘grocerage,’ had been a devotée of the stage, pursuing acting until she realised the theatre would never pay. And being able to pay her way became increasingly important when her father, who in the eighteen-eighties developed a chain of grocery shops, forsook his business for politics, holding the North Kensington seat as a radical Liberal MP. Beguiled by Westminster, he subsequently lost control of his family business and, eventually, even of his home – which led to Kate taking up work as a paid organiser for the New Constitutional Society.

It is extraordinary that, even after a hundred years, new primary material such as Kate Parry Frye’s Diary has surfaced, allowing us access to the experience, without the interference of hindsight, of the life of a Suffragette. Recognising the value of Kate’s experience, I decided that rather than selling the manuscripts of her diaries I would edit the entries for 1911-1915 as Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary.

With Kate as a guide, readers may trace the ‘Votes for Women’ campaign day by day, as she knocks on doors, arranges meetings, trembles on platforms, speaks from carts in market squares, village greens, and seaside piers – enduring indifference, incivility and even the threat of firecrackers under her skirt. Her words bring to life the experience of the itinerant organiser – a world of train journeys, of complicated luggage conveyance, of hotels and hotel flirtations, of boarding houses, of landladies, and of the quaintness of fellow boarders. No other diary gives such an extensive account of the working life of a Suffragette, one who had an eye for the grand tableau as well as the minutiae, such as producing an advertisement for a village meeting or, as in the following entries, campaigning in Whitechapel.

Saturday September 27th 1913

Another boiling day. On top of a bus to Whitechapel. A meeting of women and girls who had been before – and a tea given by Miss Raynsford Jackson who afterwards addressed them and could not be heard beyond the first row, I should say, and in any case was very tedious. However one girl ended by playing the piano and made a deafening row. Miss Mansell, Miss McGowan’s nice friend, was there – she is a dear – she did all the tea. I chatted and handed round. The girls were so nice – nearly all Jewesses. The pitiful tales they tell of the sweated work is awful – and they are so intelligent – and quite well dressed. The Jews are an example to the gentile in that way.

Wednesday October 1st 1913

Bus to Piccadilly Circus – lunch at [Eustace] Miles [a vegetarian restaurant] – by train from Charing Cross to St Mary’s [the nearest railway station to the Whitechapel Committee room], getting there at two o’clock. I need not have hurried as we did not start out on our Poster Parade until three o’clock. Miss McGowan, Miss Simeon, Miss Goddard and myself, with Miss Mansell to help give out bills. It was a great success – the Whitechapel folks were very entertained and very few were rude and rough. We got back about five all very tired – it is tiring work, the pace is so slow and one has to be so keenly on the lookout for everything – and the mud and dirt in the gutter is so horrid. Then after tea I went off to Mark Lane again to give out bills. Had some sardines on toast at Lyons and to the Committee room 136 Whitechapel Rd at 7.45pm where I was joined by Mrs Merivale Mayer and Mrs Kerr and we all went off to Mile End Waste for an open-air meeting at eight o’clock. I gave out hand bills and chatted to the crowd. Some of our girl friends were there – they are so affectionate and nice. I was simply dead from standing and did not get home until 10.45pm. I was so tired I wept as I walked from the station.

Kate Frye’s account of the activities of the New Constitutional Society is the fullest that exists. Nothing of the Society’s archive has survived, presumably destroyed when the society dissolved in 1918, once the vote was won and its work done. Although she never again had reason to venture into the East End, the Suffrage movement had opened Kate’s eyes to the deprivations endured by its people and gave reality to her hope that after women got the vote ‘something would be done’..

Members of the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage in their workroom.

“It was all simply magnificent, 70,000 of us, five abreast, and some of the sections were just wonderful – a real pageant and I enjoyed myself tremendously. It started at 5.30pm and it was not much after 6pm when we were off. We were in a splendid position. The end had not left the Embankment before we started the meeting at 8.30pm, seven miles, a thousand banners and seventy bands. We were just behind one and it was quite lovely marching to it. We all kept time to it and at least walked well. Several of the onlookers I heard say that ours was the smartest section. We went along at a good steady pace – not nearly so much stopping about as usual and it was lovely to be moving, though I had not found the wait long. Such crowds – perfectly wonderful – there couldn’t have been many more and they must have waited hours for a good view. The stands were crowded too and one could see the men lurking in the Clubs – some of them looking very disagreeably.”

Kate Parry Frye’s Diary entry for Thursday May 21st 1914

Kate kept one of the handbills that she distributed around Whitechapel – The New Constitutional Society translated their message into Yiddish. Thursday, October 2nd 1913 “To Whitechapel at 10.30am. Miss Goddard was the only one who turned up till afternoon so she and I went off to the Docks to give out handbills. We had a funny morning, as I got arrested twice. The first time by a young and foolish Policeman for holding a Public Meeting where it was not allowed. ‘Now then young woman come out of this,’ with a most savage pull at my arm, nearly knocking me over. It was so absurd.”

In February 1910, Members of the House of Commons formed what was termed the Conciliation Committee to prepare a private member Conciliation Bill acceptable to all parties. The Bill passed its first reading on 14th June and, in order to give the campaign maximum publicity, the Women’s Social & Political Union and another militant society, the Women’s Freedom League, joined together with other societies to mount a spectacular procession through London. Kate, to her delight, marched with the actresses,“Everyone was interested in us and sympathisers to the cause called out ‘Well done, Actresses.'”

Black Friday‚ 18th November 1910. At a meeting in Caxton Hall, members such as Kate, heard the news that, with the two houses locked in a battle for supremacy, Parliament was to be dissolved. This meant that the Conciliation Bill would be killed. In retaliation, the WSPU immediately ended the truce it and prepared to resume militant tactics. A deputation of three hundred women, divided into groups of ten, set out from Caxton Hall for Parliament and in Parliament Sq met with violence such as they had never previously encountered. This day has gone down in Suffrage history as Black Friday. As Kate reported, “I was almost struck dumb and I felt sick for hours. It was a most horrible experience. I have rarely been in anything more unpleasant. It was ghastly and the loud laughter & hideous remarks of the men – so-called gentlemen – even of the correctly attired top-hatted kind, was truly awful.”

Saturday, July 3rd 1926, Mrs Pankhurst addressing the last Suffrage Demonstration – to persuade the government to give votes to women at twenty-one‚ and for peeresses in their own right to be given a seat in the House of Lords. “[After lunch] changed, off with John‚ bus to Marble Arch and walked to Hyde Park Corner. Sat a little then saw the procession of women for equal franchise rights and to the various meetings and groups. Heard Mrs Pankhurst and she was quite delightful.”

Photograph of Kate Parry Frye at Berghers Hill in the thirties.

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary – edited by Elizabeth Crawford can be ordered direct from the publisher Francis Boutle and copies are on sale in bookshops including Brick Lane Bookshop, Broadway Books, Newham Bookshop, Stoke Newington Bookshop and London Review Bookshop.

In the Kitchen at Headway East

Joseph Trivelli, Head Chef at the River Cafe, spends his day off each week working in the kitchen with members at Headway East, the community centre for people who have acquired brain injuries, either through accident or some other cause. Last week, Joseph and his team prepared a three-course dinner for thirty-five as a fund-raiser for the centre, so Contributing Photographer Patricia Niven and I went along to see what was cooking.

Even at three in the afternoon, we were welcomed by an appetising fragrance in the kitchen as the Joseph’s proteges Oliver, Jason and Keith put together fillets of lemon sole with hops, peas, olives, fresh oregano and onions, ready for baking in paper packets. Joseph’s dinner comprised a menu of seasonal ingredients that could be prepared in advance and then cooked freshly to be delivered from the oven to the table that evening. By five, we ogled as they rolled sheets of pasta through the machine and then piped a filling of salt cold onto it in bite-sized portions that were wrapped up into convincingly professional ravioli.

At six, Oliver sliced kohlrabi and Jason chopped carrots as crudites for starters, then Keith cut up tomatoes to make a sauce for the ravioli. Meanwhile, Joseph made ice cream to accompany the rhubarb served with Oliver’s shortbread. And there was just time for the team to slip into their chef’s whites in order to welcome the diners as they began to arrive at seven. They had paid £30 each for their dinner served at long tables under a railway arch.

“I’m not just here for them, I’m here so I can try things I couldn’t do at work,” Joseph Trivelli admitted to me, quietly proud of his team as service commenced.

Oliver Herz

” I made the shortbread to go with the rhubarb – I think I’ve got a slight advantage in that my wife is from Scotland. I’ve been coming to Headway since 2003 and cooking breakfast for a dozen people. After my head injury, I lost my job in local government and was given my pension. At first, I came here while I was doing rehabilitation and I liked it, and now I’ve been coming for over ten years. I’ve always been good in the kitchen, though I’ve never been paid to cook. I think it’s to do with the fact that I’m greedy, and I have an allotment so I don’t just cook food, I grow it.”

Jason Lennon

“I was told by one of my support-workers that there was a place where you could come to relax and enjoy the good part of life. Three years, I’ve been coming here to Headway now and it’s really been true. Where I live, it’s not a very nice place for me to be but I have a garden in Abbey Rd where I go most days and grow herbs, carrots, cauliflowers, cabbages and aubergines. I’ve had it five years. I eat the things I grow in vegetable stew. My mother taught me to cook back in Jamaica and I cook at home.”

Keith Emanuel

“I help in the kitchen every Friday at Headway, cooking for the members. On Tuesdays and Thursdays, I help out at St Mary’s Secret Garden and I do voluntary gardening for Homerton Hospital – I’m making a garden for the patients. I had a brain haemorrhage about thirteen years ago and they sent me to a place for handicapped people because there was nowhere for those who had a brain haemorrhage. But then someone told me about this place and I’ve been coming here about eight years. Before all this, I used to do catering and I worked for a big catering firm in Oxford St for seven years.”

Joseph Trivelli, Head Chef at The River Cafe

“I was at a bit of a loose end one day and they had built a pizza oven here, so they asked me over to teach people to make pizza dough for a party. But I couldn’t resist coming back to make pizzas myself and it grew from there. I’ve been coming in every week since Christmas on my day off from The River Cafe and we make lunch for thirty members for a couple of pounds each. Tonight we are cooking dinner for thirty-five people as fundraiser, but this is just the very, very beginning of what we could do.”

Preparing the fish parcels.

Lemon sole with hops, peas, olives, spring onions, and fresh oregano, baked in a paper parcel.

Preparing fresh ravioli filled with salt cod.

Serving the ravioli

Photographs copyright © Patricia Niven

If you would like to attend a dinner cooked by Joseph Trivelli and his team contact Headway East

You may also like to read about

Nicholas Sack in the City

“I’ve done a lot of loitering on street corners,” Photographer Nicholas Sack confessed to me shamelessly, when I quizzed him about his curious pictures of the workers in the City of London, “it might take several visits to the same spot for the right arrangement of people to form in the viewfinder.”

Nicholas’ photographs brilliantly capture the strange dynamic which exists upon the pavements of the City in contrast to the narrow streets of the East End, where people jostle each other as they wander through the crowded markets. In the City, pedestrians maintain a respectful distance as they walk and the overbearing corporate architecture creates tense spaces which are not designed for lingering. “The smart and unshowy attire of office workers appeals to my love of order,” Nicholas admitted to me, revealing his equivocation on the subject, “yet the human figure can look physically rather absurd, especially when walking – Lowry knew that, and so did John Cleese.”

Working on film and framing his subjects immaculately, Nicholas uses photography to expose the spatial dynamics of power with humour and sardonic poetry. “Over many years of stalking the streets, I have learned how to lift things out of the ordinary.” he confided to me – exercising an anthropologist’s scrutiny upon the ways of that mysterious tribe which inhabits the Square Mile.

Photographs copyright © Nicholas Sack

“Uncommon Ground,” Nicholas Sack’s new book of photography is available here