At 37 Spital Square

Drawing of 37 Spital Sq by Joanna Moore

What could be a better showcase for the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings than the fine eighteenth century house they restored in Spital Sq which serves as their headquarters? This magnificent tottering pile is the last surviving Georgian mansion of the entire square once lined with such dwellings, which traced the outline of the former Priory of St Mary Spital that was established in 1187. Indeed, pieces of Medieval stonework from the old Priory buildings are still visible, tucked into the foundations of 37 Spital Sq.

Originally constructed in the seventeen-forties as the home of Peter Ogier, a wealthy Huguenot silk merchant, the house has been through many incarnations both as dwelling and workplace until the Society took it on in a rundown state in 1981 and brought it back to life. As a Society that counted William Morris, John Ruskin, Thomas Hardy, Beatrix Potter, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and John Betjeman among its members, the SPAB is irresistible to any writer with a passion for old buildings, and 37 Spital Sq certainly does not disappoint.

Neither museum or showhouse, the building has preserved its shabby charm as a working environment where people sit absorbed at their desks in elegantly proportioned rooms, surrounded by all the clutter of their activities and a few well-chosen paintings and pieces of old furniture. With staircases that seem to ascend forever, plenty of hidden corners and architectural idiosyncrasies, 37 Spital Sq is a house that invites you to ramble around – which is exactly what I did yesterday, matching up pictures in the Society’s archives of the building in 1981 with the same spaces as they are now.

1981

2013

Huguenot silk weaver Peter Ogier is believed to have built 37 Spital Square in the seventeen-forties.

You may also like to read about

Philip Venning, former Director of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings

Bill Crome, the Window Cleaner who sees Ghosts in Spital Sq

and these other renovations in Spitalfields

Paul Gardner, Paper Bag Baron

“There’s so few shops left selling paper bags”

Every now and again, the time comes to pay a call upon my friend Paul Gardner, the paper bag baron and fourth generation proprietor of the Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen, the oldest family business in Spitalfields. The occasion for my visit yesterday was to pick up a hundred bags in which to mail the famous tea-towels yet, as usual with Gardners, it was not just bags that I came away with but a whole collection of stories too.

“They used to throw four pound iron weights in the air and head them,” Paul told me, in illustration of the reckless spirit of market people, and I was rapt. Then Metin arrived, a seller of t-shirts and jeans from Covent Garden, immediately excited to see Paul’s face. “I came in here as a kid when my dad bought his bags, and you were here as a kid too, and I never thought I’d come back to buy my own bags from you,” he contemplated fondly while Paul totted up his order. “My father believed kids had to work and I came at four in the morning and wheeled the barrow round the Spitalfields Market for him.” Metin continued, in disbelief at his own past,“He was brought up on a farm in Turkey and he’d pick a box of fruit and he’d want to buy that exact one. It was the same with meat in Smithfield, he’d stick his nose in a box of lamb and smell it, and say ‘I want this one.'”

Our collective moment of delighted reminiscence was dispelled as quickly as it gathered, since Metin had to avoid the traffic warden. When he left with a large order on his shoulder, another gentleman entered who wanted just two large paper carrier bags, which Paul was happy to sell him.

Then I took the opportunity of a brief lull in the passing trade, on that quiet Monday morning, to ask Paul about the wonderful old catalogue of images for overprinting onto bags dating from his father’s era that he had showed me and, unexpectedly, I became party to this brief history of paper bags in Spitalfields.

“While the Fruit & Vegetable Market was here, 95% of our customers were greengrocers. In the days when I first started in 1971 – when I was sixteen or seventeen – I used to get here at quarter to six and until ten o’ clock there’d be a big line of greengrocers outside. They’d come early to the market for the pick of the fruit, though there were also those who came late and bought what was left to sell it cheap next day. Sometimes, they’d even sort the stuff that was being thrown out, and try and sell it on the same day.

They all bought brown paper bags at seven shillings and sixpence per thousand, but the better class of greengrocer bought white craft bags – they were seen as better quality. If you have a printed bag, you need to order a minimum of fifty thousand at a time and most of the customers did not want to lay out that much money, so they just bought them ready-printed with ‘Fresh daily.’ I used to sell printed brown paper carrier bags with a background of tomatoes too, until plastic carriers came in. They were very popular because people could sell them for five pence. Now it’s gone full circle and plastic is vilified – though you can reuse them. My dad died in 1968 and plastic bags came in just before that, in 1967.

There was very little profit in bags then but we had a big turrnover, we sold two hundred thousand bags a week. Yet once the Market went, that was the end of that – I lost 90% of my customers. At one time, there were thirty-five barrows selling fruit & vegetables in Petticoat Lane and now there’s only two. But then the little markets grew up, Columbia Rd, Upmarket, the Antiques Market. The size of individual orders has gone down but the number of my customers has gone up.

Nowadays people buy plain bags and print designs themselves, the old fashioned way, with a rubber stamp. When I first came here there were just brown and white bags, but now we’ve got leopard skin, zebra and tiger stripes, polka dots and stripes – every variety you can imagine.“

These days, Paul is wary to undertake large orders for printed bags, warning me of the risks of making an error and quoting a cautionary tale of a fellow bag seller who once invested in stock to match the distinctive hue of a famous chain store that was his customer, only to discover the shop had changed its colour. Yet, even if no-one orders printed bags today, Paul still treasures his father’s album of sample illustrations for bags from more than half a century ago, cherishing it among all the other mementos that he keeps of previous generations which tell the story of his beloved Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen.

And thus passed another morning at Spitalfields’ one-hundred-and-forty-year-old paper bag shop.

“the better class of greengrocer bought white craft bags – they were seen as better quality”

Stock illustrations for paper bags dating from the era of Paul’s father Roy.

Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen, 149 Commercial St, London E1 6BJ (6:30am – 2:30pm, Monday to Friday)

You may like to read these other stories about Gardners Market Sundriesmen

Paul Gardner, Paper Bag Seller

At Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen

Joan Rose at Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen

In Search Of Other Worlds

Parallel worlds in Bethnal Green

On Sundays, when the crowds throng Brick Lane, I commonly go roving beyond beyond my familiar streets. Upon other occasions, I have gone off to seek snowmen or cherry blossom or desire paths, but yesterday, I went in search of other worlds.

Just as in many mythologies, rivers signify the crossing point between this world and the otherworld, so in my experience of London, shopfronts are often the portals to some of the most interesting worlds I have discovered – such as W.F.Arber & Co Ltd in the Roman Rd or Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen in Commercial St.

Yet such is the nature of my fancy, I only have to see “world” above the fascia of a shop to conjure an extravagant fantasy of what might lie beyond – in “Bargain World” or “Shoe World.” For this reason, I have never visited most of the shops in these photographs because the pleasurable experience of viewing the frontage alone is sufficient to satisfy my imagination. In fact, closed shops such as the antique shops of Kensington Church St and the Fulham Rd where once I used to go window-shopping on Sundays – peering through the gloom into the infinite recession of the shadowy depth beyond – are the most exciting of all. Tell me I am not the only one to have been seduced by the mystery of the Savoy Cafe at 20 Norton Folgate, repossessed by the City of London over a year ago yet untouched inside, with bottles of milk and drinks still visible in the fridge after all this time.

In the cosmology of Bethnal Green, you might expect the juxtaposition of Smokers World and Dreamland Linens to equate with the familiar dialectic of Heaven and Hell in the Medieval imagination. Yet while Dreamland Linens is an ethereal zone of pleasure and delight, draped with luxurious floaty textiles, Smokers World does not the deliver the Gothic chill of a myriad chain-smokers coughing up their lungs in the blue fog of Benson & Hedges, instead it is merely a defunct newsagent that serves as an extension of the curtain shop next door. Thus, in Bethnal Green, the apocalyptic battle of opposing forces has been unequivocably resolved with Dreamland Linens triumphant over Smokers’ World.

London is a city of multiple worlds and no-one can know them all. Sometimes, I get vertiginous feelings trying the envisage the infinite multiplicity of activities surrounding me in the capital – and seeing “World” above a shopfront is my personal imaginative trigger to day-dreaming in this vein.

A portal to a thrifty universe in Bethnal Green.

The gateway to a footwear cosmos in Bethnal Green.

The entry to Frame Land in Brick Lane.

Dosa World offers a universe of South Indian cuisine in Hanbury St

A textile environment at Denim World in Whitechapel.

Michelin man beckons you to an enclave of tyres beneath the arches.

The door to an entire continent of fashion in Dalston.

Cloud Cuckoo Land in Camden Passage looks promising.

Dare you enter the Mad World of 35,000 fancy dress outfits in a Shoreditch basement?

No longer a church, Westland is in fact a showroom for large, spectacular items of architectural salvage.

Going Places in Ridley Rd Market

You may also like to take a look at

The Docks of Old London

Within living memory, the busiest port in the world was here in the East End but now the docks of old London have all gone. Yet when I walk through the colossal new developments that occupy these locations today, I cannot resist a sense they are merely contingent and that those monumental earlier structures, above and below the surface, still define the nature of these places. And these glass slides, created a century ago by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society for magic lantern shows at the Bishopsgate Institute, evoke the potent reality of that former world vividly for me.

Two centuries ago, the docks which had existed east of the City of London since Roman times, began an ambitious expansion to accommodate the vast deliveries of raw materials from the colonies. Those resources supplied the growing appetite of manufacturing industry, transforming them into finished products that were exported back to the world, fuelling an ascendant spiral of affluence for Britain.

Despite this infinite wealth of Empire, many lived and worked in poor conditions without any benefit of the riches that their labour served to create and, in the nineteenth century, the docks became the arena within which the drama of organised labour first made its impact upon the national consciousness – winning the sympathy of the wider population for those working in a dangerous occupation for a meagre reward.

Eventually, after generations of struggle, the entire industry was swept away to be replaced by Rupert Murdoch’s Fortress Wapping and a new centre for the financial centre at Canary Wharf. Yet everyone that I have spoken with who worked in the Docks carries a sense of pride at participating in this collective endeavour upon such a gargantuan scale, and of delight at encountering other cultures, and of romance at savouring rare produce – all delivered upon the rising waters of the Thames.

Deptford Dock Yard, c. 1920

Atlantic Transport Liner “Minnewaska” – The Blue Star Liner “Almeda” in the entrance lock to King George V Dock on the completion of her maiden voyage with passengers from the Argentine, April 6th, 1927.

Timber in London Docks, c. 1920

Wool in London Docks, c. 1920

Ivory Floor at London Dock, c. 1920

Crescent wine vaults at London Dock – note curious fungoid growths, c. 1920

Unloading grain – London Docks, c. 1920

Tobacco in London Docks, c. 1920

Royal Albert Dock, c. 1920

Cold Store at the Royal Albert Dock showing covered conveyors, c. 1920

Quayside at Royal Albert Dock, c. 1920

Surrey Commercial Dock, c. 1920

Barring Creek, c. 1920

Wapping Pier Head, c. 1920

Pool of London, c. 1920

Mammoth crane, c. 1920

Greenwich School – Training ship, c. 1910

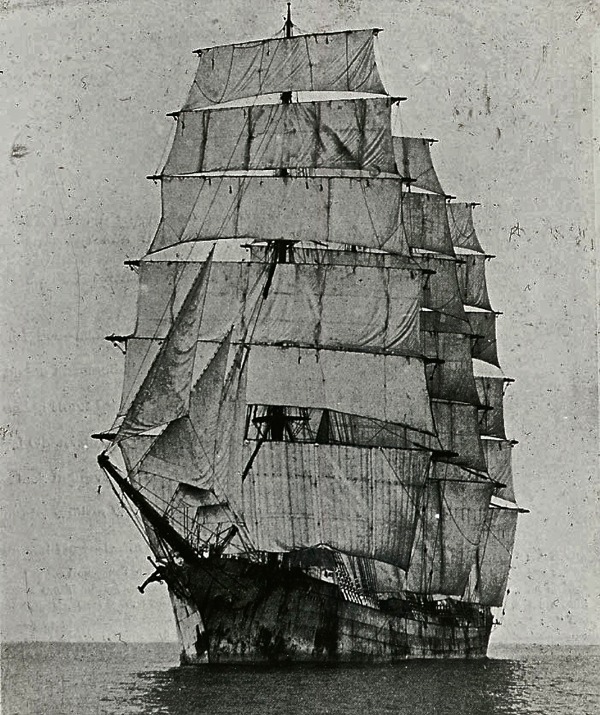

The Hougoumont on the Thames, c. 1920

Images copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to read these other stories about the London Docks

Views from a Dinghy by John Claridge

Along the Thames With Tony Bock

Whistler in Limehouse & Wapping

Dickens in Shadwell & Limehouse

Madge Darby, Historian of Wapping

and these other glass slides of Old London

The High Days & Holidays of Old London

The Fogs & Smogs of Old London

The Forgotten Corners of Old London

The Statues & Effigies of Old London

The City Churches of Old London

Brian Gurtler, Tea-Towel Printer

In a hidden courtyard workshop close to Brick Lane, Brian Gurtler, Textile Designer & Printer, of Dot Productions has been busy these last few days producing the limited edition of one hundred of Adam Dant’s tea-towels bought by readers last week.

When we conceived these tea-towels “In Celebration of the Culture of the Labouring Classes,” we did not dare to hope that the Marquis of Lansdowne would be saved, and so we chose to print only one hundred and sell them as cheaply as possible – which meant they sold out in hours. Since Hackney Council refused permission to demolish the pub, leaving the Geffrye Museum with no choice but the restore it, these modest tea-towels have become prized trophies commemorating this joyous moment.

I could not resist paying a visit to the workshop to watch Brian conjure them into existence and take the opportunity of meeting this skilled craftsman who has applied himself to printing Adam’s witty design with such relaxed expertise. Brian prints forty at a time, turning the wheel that delivers each of the screens to the printing surface and applying the colours methodically with deceptive ease, until his drying rack is full.

Then it is necessary to seek refreshment at The Pride of Spitalfields before the next batch can be printed and, yesterday, Brian persuaded me to join him there. “I need half an hour to get my back working again,” he admitted with genial candour. Such is the working life of a master screen-printer in Spitalfields.

“I started off here in a workshop just opposite Shoreditch Church in 1988. After graduating from Farnham School of Art where I studied printing, I moved to London to work with a company that did limited edition prints for hotels and restaurants. A fellow student from Farnham also worked there, and he said ‘We’ve got to be able to do better than this.’ So we set up own company printing t-shirts with images from fine art and the British Museum was our first customer. We did them for National Gallery and the Tate too.

We were looking for a space where we could live and work because we couldn’t afford both. Our landlord was Ray Bard who bought everything inside the Shoreditch Triangle at that time. It was mostly derelict property then, blighted because everyone assumed the City would advance north and it would all be compulsorily purchased. Consequently, we got three thousand square feet for eighty pounds a week. We set up our machines and slept on the floor on futons. If you made a little money, you could live like a king. We ate breakfast at the beigel shop and you could go down Brick Lane and get a curry for under five pounds – I remember a place where you could get five vegetable dishes for three pounds sixty. We drank in the Bricklayers’ Arms in Rivington St, and there would be only three people in there and a lovely landlady called Lil. On Sunday mornings, she laid out prawns, cheese and roast potatoes to encourage customers, it was a proper East End Pub, spit and sawdust.

I came to Links Yard off Brick Lane after we downsized because of the financial climate. The bottom fell out of the market when people could order printed t-shirts from China over the internet at a tenth of the price. I went from employing people to a one-man-band, and Spitalfields Small Business Association gave me this workshop at an affordable rent. For the past ten years, almost all my work has been for the fashion industry – every label you care to mention – creating samples of pieces that involve printing on textiles. It’s very rare to find anyone in this country that does this now. Once I have created the prototypes which the designers use to get orders then the garments are manufactured in China.

I wouldn’t want to be a young Bengali, Jewish or East European kid coming to London today and trying to make it happen. The Huguenots wouldn’t come to Spitalfields now because they couldn’t afford it! That’s what I was when I came here, a poor itinerant, trying to start my own business. I’ve been going twenty-five years. I’m not trying just to make money, I’ve got a degree in printing and I’m good at what I do.”

Adam’s tea-towel design

Each of the silk screens on the wheel carries one of the different colours that overlay to make the design.

The completed tea-towels

Brian Gurtler, textile designer & printer.

Artist Adam Dant signs and numbers each tea-towel with a laundry marker.

Tea-towel orders will be despatched early next week.

Henry Silk, Artist & Basket Maker

Of all the painters that comprised the East London Group, I rate none more highly than Henry Silk and so I am delighted that I was able to persuade David Buckman, author of the authoritative history From Bow to Biennale : Artists of The East London Group, to write this feature.

At his Uncle Abraham’s basket shop in Bow

The recent exhibition of East London Group painters in Bloomsbury – the first in eighty years – raised the question: Which of the members most closely embodied what the Group stood for ? There are many advocates for Archibald Hattemore, Elwin Hawthorne, Cecil Osborne, Harold & Walter Steggles, and Albert Turpin – all painters from backgrounds that were not arty in any conventional sense who became inspired by their teacher John Cooper, the founder of the Group. Yet for some, the shadowy figure of Henry Silk, creator of highly personal and poetically understated images, is pre-eminent.

Silk’s talent was quickly recognised as far away as America, even while the Group was just establishing itself in the early thirties. In December 1930, when the second Group show was held in the West End at Alex. Reid & Lefevre, the national press reported that over two-thirds of pictures were sold, listing a batch of works bought by public collections. The Daily Telegraph and Sunday Times revealed that, in addition to British purchases, the far-away Public Gallery of Toledo in Ohio had bought Silk’s ‘Still Life’ for six guineas.

American links continued when, early in 1933, Helen McCloy filing an insightful survey of the group’s achievements for the Boston Evening Transcript, judged Silk to have “the keenest technical sense of all the limitations and possibilities of paint.” Coincident with McCloy’s article, Hope Christie Skillman in the College Art Association’s publication Parnassus, distinguished Silk as “perhaps the most original and personal of the Group,” finding in his works such as The Railway Track, The Platelayers, The Tyre Dump and The Wireless Set, “beauty where we were taught not to see it.”

Silk’s early life is obscure. He was an East Ender, born on Christmas Day 1883, who worked as a basket maker for an uncle, Abraham Silk, at his workshop and shop in the Bow Rd. Fruit baskets were in great demand then and men making baskets became features of Silk’s pictures. “He used to work for three weeks at basket-making and spend the fourth in the pub,” Group member Walter Steggles remembered, describing Silk’s erratic work and drink habits. Yet Steggles also spoke of Silk with affection, admitting “He was a kind-hearted man who always looked older than his years.”

Silk was the uncle of Elwin Hawthorne, one of the leading members of the group, and lived for a time with that family at 11 Rounton Rd in Bow. Elwin’s widow Lilian – who, as Lilian Leahy, also showed with the group – remembered Silk as “generous to others but mean to himself. He would use an old canvas if someone gave it to him rather than buy a new one.” This make-do-and-mend ethos was common among the often-hard-up Group members when it came to framing too. Cooper directed them to E. R. Skillen & Co, in Lamb’s Conduit St, where Walter Steggles used to buy old frames that could be cut to size.

During the First World War, the young Silk was already sketching. Even on military service in his early thirties, during which he was gassed, he would draw on whatever he could find to hand. By the mid-twenties, he was attending classes at the Bethnal Green Men’s Institute and exhibited when the Art Club had its debut show at Bethnal Green Museum early in 1924. The Daily Chronicle ran a substantial account of the spring 1927 exhibition, highlighting Henry Silk, the basket maker, whose paintings depicted “Zeppelins and were bought by an officer ‘for a bob.’”

Yorkshireman, John Cooper, who had trained at The Slade, taught at Bethnal Green and, when he moved to evening classes at the Bow & Bromley Evening Institute, he took many students with him including George Board, Archibald Hattemore, Elwin Hawthorne, Henry Silk, the Steggles brothers and Albert Turpin. They were members of the East London Art Club that had its exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in the winter of 1928, part of which transferred to what is now the Tate Britain early in 1929. These activities prompted the series of Lefevre Galleries annual East London Group shows throughout the thirties, with their sales to many notable private collectors and public galleries, and huge media coverage.

Henry Silk was a prolific artist. He contributed a significant number of works to the Whitechapel show in 1928, remained a significant exhibitor at the East London Group-associated appearances, showed with the Toynbee Art Club and at Thos Agnew & Sons. Among his prestigious buyers were the eminent dealer Sir Joseph Duveen, Tate director Charles Aitken and the poet and artist Laurence Binyon. Another was the writer J. B. Priestley, Cooper’s friend, who over the years garnered an impressive and well-chosen modern picture collection. Silk was also regarded highly by his East London Group peers, Murroe FitzGerald, Hawthorne’s wife Lilian and Walter Steggles, who all acquired works of his.

As each of the East London Group artists acquired individual followings as a result of the annual and mixed exhibitions, the Lefevre Galleries astutely organised solo shows for several of them. Elwin Hawthorne, Brynhild Parker and the brothers Harold & Walter Steggles all benefited. Yet, in advance of these, in 1931 Silk had a solo show of watercolours at the recently established gallery Walter Bull & Sanders Ltd, in Cork St. The small exhibition was characterised by an array of still lifes and interiors. Writing in The Studio magazine two years earlier, having visited Cooper’s Bow classe, F. G. Stone noted that Silk often saw “a perfect design from an unusual angle, and he has a Van Goghian love of chairs and all simple things.”

Cooper urged his students to paint the world around them and Silk met the challenge by depicting landscapes near his home in the East End, also sketching while on holiday in Southend and as far away as Edinburgh. Writing the foreword to the catalogue of the second group exhibition at Lefevre in December 1930, the critic R. H. Wilenski said that French artists were fascinated by the “cool, frail London light.” and many asked him “what English artists have made these aspects of London the essential subject of their work.” He responded, “The next time a French artist talks to me in this manner I shall tell him of the East London Group, and the members’ names that I shall mention first in this connection will be Elwin Hawthorne, W. J. Steggles and Henry Silk.”

Even after the East London Group held its final show at Lefevre in 1936, Henry Silk continued to show in the East End, until his death of cancer aged only sixty-four on September 24th, 1948.

Thorpe Bay

St James’ Rd, Old Ford

Old Houses, Bow (Walter Steggles Bequest)

My Lady Nicotine

Snow (Walter Steggles Bequest)

Still Life (Walter Steggles Bequest)

Basket Makers (Courtesy of Dorian Osborne)

Boots, Polish and Brushes

The Bedroom

Bedside chair (Courtesy of Dorian Osborne)

Hat on table, 1932 (courtesy of Doncaster Museum)

The view from 11 Rounton Rd, Bow, photographed by Elwin Hawthorne

You may also like to read David Buckman’s other features about the East London Group

From Bow to Biennale: Artists of the East London Group by David Buckman can be ordered direct from the publisher Francis Boutle and copies are on sale in bookshops including Brick Lane Bookshop, Broadway Books, Newham Bookshop, Stoke Newington Bookshop, London Review Bookshop, Town House, Daunt Books, Foyles, Hatchards and Tate Bookshop.

Clive Murphy, Up In Lights

[youtube rmQzAUbb1Tc nolink]

film by Sebastian Sharples

Originally published in 1980, Clive Murphy’s wonderfully candid account of Marjorie Graham – the chorus girl who fell upon hard times and became a lavatory attendant at the Metropole Cinema in Victoria – is to be republished by Pan Macmillan later this month. Simultaneously heartwarming and heartbreaking, Marjorie’s wit and resilient good humour in the face of the perils of show business life make this a compelling read.

In collaboration with our friends at Labour & Wait, we are proud to be hosting a tea party in celebration of Clive at the Bishopsgate Institute at 2pm on Saturday 25th May and we hope you will join us for what promises to be a sparkling literary event. Distinguished actress and Spitalfields resident Siân Phillips will be with reading selections from the book and Clive’s favourite lemon sponge will be served. Admission is free but capacity is limited, so we advise you to call 020 7392 9200 and reserve your ticket at once.

Clive Murphy recalls the creation of UP IN LIGHTS

“In September 1970, I finished recording the memoirs of a retired London lavatory attendant. He lived, with his wife Johanna, in the dank basement of a house in Pimlico where I’d rented a bedsitter.

Moving a year later to a bedsitter a few streets away, whom should I find living there in another dank basement, with her husband Jock, but Marjorie Graham, a retired female lavatory attendant, as happy to reminisce as her male predecessor.

Coincidence, Luck or Fate, call it what you will – by the end of 1973 I was ready to offer publishers my brace of memoirs which would make a fortune for all concerned. My attempts, though, to arouse interest were firstly rejected out of hand. One editor replied, ‘Write to us again when you’ve recorded an attendant that’s a hermaphrodite and we might publish them as a trio.’ Marjorie and her male counterpart were only taken on seven years later, along with other books I’d taped, by the publisher Dennis Dobson, to the delight, I’m glad to say, of many readers. The going had often been rough for me. A whole book per person takes more stamina than a short portrait . . .

Ronald Blythe wrote of Marjorie as a ‘dancing, easyish, drinking lady whose fate it was never quite to get through,’ reading her was ‘like eating meringues sprayed with “Evening in Paris.”’ Though he failed to mention her sparkle and her sense of fun in face of tragedy, I prefer John Betjeman’s enigmatic ‘deeply moving and authentic and compulsive reading. Her story has the full gloom of Tottenham Court Rd Underground Station and the precariousness of being alive. The lady is loveable indeed. My word what a good book.’

Sadly, Marjorie died of a heart attack aboard a bus in Victoria in 1974 before seeing her name up at least in literary lights. But now they are to be up – I hope she is looking down – in lights that are even brighter.”

Clive Murphy, 19th February 2013, Spitalfields

Sian Phillips, distinguished actress and Spitalfields resident, will be reading from “Up In Lights.”

Portrait of Sian Phillips © Lucinda Douglas-Menzies

You may like to read my other stories about Clive Murphy