George Dodd’s Spitalfields, 1842

George Dodd came to Spitalfields to write this account for Charles Knight’s LONDON published in 1842. Dodds recalls the rural East End that still lingered in the collective memory and described the East End of weavers living in ramshackle timber and plaster dwellings which in his century would be “redeveloped” out of existence by the rising tide of brick terraces, erasing the history that existed before.

Spitalfields Market

It is not easy to express a general idea respecting Spitalfields as a district. There is a parish of that name but this parish contains a small portion only of the silk weavers and it is probable that most persons apply the term Spitalfields to the whole district where the weavers reside. In this enlarged acceptation, we will lay down something like a boundary in the following manner – begin at Shoreditch Church and proceed along the Hackney Rd till it is intersected by Regent’s Canal, follow the course of the canal to Mile End Rd and then proceed westward through Whitechapel to Aldgate, through Houndsditch to Bishopsgate, and thence northward to where the tour commenced.

This boundary encloses an irregularly-shaped district in which nearly the whole of the weavers reside and these weavers are universally known as “Spitalfields” weavers. Indeed, the entire district is frequently called Spitalfields although including large portions of Bethnal Green, Shoreditch, Whitechapel and Mile End New Town. By far the larger portion of this extensive district was open fields until comparatively modern times. Bethnal Green was really a green and Spitalfields was covered with grassy sward in the last century.

It may now not unreasonably be asked, what is “Spitalfields”? A street called Crispin St on the western side of Spitalfields Market is nearly coincident in position with the eastern wall of the Old Artillery Ground and this wall separated the Ground from the Fields which stretched out far eastward. Great indeed is the change which this portion of the district has undergone. Rows of houses, inhabited by weavers and other humble persons, and pent up far too close for the maintenance of health, now cover the green spot now known as Spitalfields.

In the evidence taken before a Committee in the House of Commons on the silk trade in 1831-2, it was stated that the population of the district in which the Spitalfields weavers resided could be no less at that time than one hundred thousand, of whom fifty thousand were entirely dependent on the silk manufacture and remaining moiety more or less dependent indirectly. The number of looms seems to vary between about fourteen to seventeen thousand and, of these, four to five thousand are unemployed in times of depression. It seems probable, as far as the means exist of determining it, that the weavers are principally English or of English origin. To the masters, however the same remark does not apply, for the names of the partners in the firms now existing, point to the French origin of manufacture in that district.

A characteristic employment or amusement of the Spitalfields weavers is the catching of birds. This is principally carried on in the months of March and October. They train “call-birds” in the most peculiar manner and there is an odd sort of emulation between them as to which of their birds will sing the longest, and the bird-catchers frequently lay considerable wagers on this, as that determines their superiority. They place them opposite each other by the width of a candle and the bird who sings the oftenest before the candle is burnt out wins the wager.

If we have, on the one hand, to record the unthrifty habits and odd propensities of the weavers, let us not forget to do them justice in other matters. In passing through Crispin St, adjoining the Spitalfields Market, we see on the western side of the way a humble building, bearing much the appearance of a weaver’s house and having the words “Mathematical Society” written up in front. Lowly and inelegant the building may be but there is a pleasure in seeing Science rear her head in a locality, even if it is humble one.

A ramble through Bethnal Green and Mile End New Town in which the weavers principally reside, presents us with many curious features illustrative of the peculiarities of the district. Proceeding through Crispin St to the Spitalfields Market, the visitor will find some of the usual arrangements of a vegetable market but potatoes, sold wholesale, form the staple commodity. He then proceeds eastwards to the Spitalfields Church, one of the “fifty new churches” built in the reign of Queen Anne and along Church St to Brick Lane. If he proceed northward up the latter, he will arrive, first, at the vast premises of Truman, Hanbury & Buxton’s brewery, and then at the Eastern Counties Railway which crosses the street at a considerable elevation. If he extends his steps eastwards, he will at once enter upon the districts inhabited by the weavers.

On passing through most of the streets, a visitor is conscious of a noiselessness, a dearth of bustle and activity. The clack of the looms is heard here and there, but not to a noisy degree. It is evident in a glance that many of the streets, all the houses were built expressly for weavers, and in walking through them we noticed the short and unhealthy appearance of the inhabitants. In one street, we met with a barber’s shop in which persons could have “a good wash for a farthing.” Here we espied a school at which children were taught “to read and work at tuppence a week.” There was a chandler’s shop at which shuttles, reeds and quills, and the smaller parts of weaving apparatus were exposed for sale in a window in company with split-peas, bundles of wood and red herrings. In one little shop, patchwork was sold at 10d, 12d and 16d a pound. At another place was a bill from the parish authorities, warning the inhabitants that they were liable to a penalty if their dwelling were kept dirty and unwholesome, and in another – we regretted this more than anything else – astrological predictions, interpretations of dreams and nativities, were to be purchased “from three pence upwards.”

In very many of the houses, the windows numbered more sheets of paper than panes of glass and no considerable number of houses were shut up altogether. We would willingly present a brighter picture, but ours is a copy from the life.

Pelham St (now Woodseer St), Spitalfields

Booth St (now Princelet St), Spitalfields

Images courtesy © Bishopsgate Insitute

Justin Gellatly’s Doughnut Recipe

Some time ago, I became hooked by the baking of Justin Gellatly (especially his sourdough bread, eccles cakes, custard tarts, hot cross buns, mince pies and doughnuts) and, over the years, I have written many stories charting his ascendancy. So it is my great pleasure to publish Justin’s recipe for doughnuts today, celebrating the rise of an heroic baker upon the publication of his first book, succinctly titled, BREAD, CAKE, DOUGHNUT, PUDDING.

Justin & Louise Gellatly

“I started making my doughnuts while working at St John Restaurant over ten years ago and, if I say so myself, they have become a bit legendary. Once you’ve had my doughnuts there is no going back.

I normally keep the fillings quite classic – custard, jam, lemon curd and apple cinnamon. But I have been developing many new flavours for this book, like my most fought-over one, the caramel custard with salted honeycomb sprinkle, which has become a bit of a signature for me, and another that I launched at Glastonbury, the violet custard with sugared violets and Parma violet sprinkle.

As in my bread recipes, I always weigh the water when I’m making doughnuts, it’s a lot more accurate than using a measuring jug.

I would recommend using a deep-fat fryer (you can pick up a Breville 3 litre one for about £30), which is a lot safer than a pan of hot oil. Either way, PLEASE be careful when using hot oil – I have had many burns and it’s really not very nice.

You will also need an electric mixer such as a Kenwood or KitchenAid, and if you don’t have a deep-fat fryer (which will have an integral thermometer) you will need a good digital thermometer to check that the oil is at the right temperature.

You can try out your own fillings by using the recipe for crème patissière and just folding in your additional filling of choice, but I am not a fan of the savoury doughnuts that are popping up in a few places.”

THE DOUGHNUT DOUGH

Makes about 20 doughnuts (about 1kg dough)

Preparation time: 45 minutes, plus proving and overnight chilling

Cooking time: 4 minutes per doughnut, fried in batches; about 30–40 minutes total

FOR THE DOUGH

500g strong white bread flour

60g caster sugar

10g fine sea salt

15g fresh yeast, crumbled

4 eggs

zest of 1⁄2 lemon

150g water

125g softened unsalted butter

FOR COOKING

about 2 litres sunflower oil, for deep-frying

FOR TOSSING

caster sugar

INSTRUCTIONS

Put all the dough ingredients apart from the butter into the bowl of an electric mixer with a beater attachment and mix on a medium speed for 8 minutes, or until the dough starts coming away from the sides and forms a ball.

Turn off the mixer and let the dough rest for 1 minute.Take care that your mixer doesn’t overheat – it needs to rest as well as the dough!

Start the mixer up again on a medium speed and slowly add the butter to the dough – about 25g at a time. Once it is all incorporated, mix on high speed for 5 minutes, until the dough is glossy, smooth and very elastic when pulled, then cover the bowl with cling film and leave to prove until it has doubled in size. Knock back the dough, then re-cover the bowl and put into the fridge to chill overnight.

The next day, take the dough out of the fridge and cut it into 50g pieces (you should get about 20). Roll them into smooth, taut, tight buns and place them on a floured baking tray, leaving plenty of room between them as you don’t want them to stick together while they prove. Cover lightly with cling film and leave for about 4 hours, or until about doubled in size.

Get your deep-fat fryer ready, or get a heavy-based saucepan and fill it up to the halfway point with rapeseed oil (please be extremely careful, as hot oil is very dangerous). Heat the oil to 180°C.

When the oil is heated to the correct temperature, carefully remove the doughnuts from the tray by sliding a floured pastry scraper underneath them, taking care not to deflate them, and put them into the oil. Do not overcrowd the fryer – do 2–3 per batch, depending on the size of your pan. Fry for 2 minutes on each side until golden brown – they puff up and float, so you may need to gently push them down after about a minute to help them colour evenly. Remove from the fryer and place on kitchen paper, then toss them in a bowl of caster sugar while still warm. Repeat until all are fried, BUT make sure the oil temperature is correct every time before you fry – if it is too high they will colour too quickly and burn, and will be raw in the middle, and if it is too low the oil will be absorbed into the doughnut and it will become greasy. Set aside to cool before filling.

To fill the doughnuts, make a hole in the crease of each one (anywhere around the white line between the fried top and bottom). Fill a piping bag with your desired filling and pipe into the doughnut until swollen with pride. Roughly 20–50g is the optimum quantity, depending on the filling; cream will be less, because it is more aerated. You can fit in more than this, but it doesn’t give such a good balance of dough to filling.

The doughnuts are best eaten straight away, but will keep in an airtight tin and can be reheated to refresh them.

CUSTARD (CRÈME PATISSÈRIE)

Makes about 900g (45g filling each for 20 doughnuts)

Preparation time: 20 minutes

Cooking time: 5 minutes

1 vanilla pod

500ml full fat milk

6 egg yolks

125g caster sugar, plus an extra 2 tablespoons

80g plain flour

200ml double cream

Slit the vanilla pod open lengthways and scrape out the seeds. Put both pod and seeds into a heavy-based saucepan with the milk and bring slowly just to the boil, to infuse the vanilla.

Meanwhile place the egg yolks and the 125g of sugar in a bowl and mix together for a few seconds, then sift in the flour and mix again.

Pour the just-boiling milk over the yolk mixture, whisking constantly to prevent curdling, then return the mixture to the saucepan. Cook over a medium heat, whisking constantly for about 5 minutes, until very thick.

Pass through a fine sieve, discarding the vanilla, and place a sheet of cling film on the surface of the custard to prevent a skin forming. Leave to cool, then refrigerate.

Whip the cream and the 2 tablespoons of sugar together until thick but not over-whipped and fold into the chilled custard.

HOW I FIRST DISCOVERED JUSTIN GELLATLY’S DOUGHNUTS

October 2009

In the past, I was never that crazy about doughnuts and though I can appreciate the pop sensibility of Dunkin Donuts and Krispy Kremes that I encountered in America with their infinite permutations of sprinkles and coloured icings, I never wanted to eat them.

Disenchantment set in at an early age. From the works of Richmal Crompton and other favourite childrens’ authors, I learnt that doughnuts were something completely delicious that all children loved to eat, but then my expectations were crushed once I actually tasted one. It was horrible, a greasy sticky lump of sponge filled with synthetic cream and a squirt of sickly red syrup at its heart. Like Proust with his madeleine, I can remember it now, only I should rather forget.

But then last week as I was buying my daily loaf at St John Bread & Wine in Commercial St, one of the waiters dropped a hint that Justin Gellatly was baking doughnuts at the weekend and my curiosity was piqued. I decided – in the interests of keeping an open mind – to give doughnuts a second shot. On Sunday on the dot of ten, opening time, I was there at St John to inspect the doughnuts, a pile of freshly baked custard-filled ones nestling together like eggs in a basket. Even as I paid for mine, another customer arrived and went straight for the doughnuts, so I knew something was up.

Once I got home, it all went into slow motion. The world dissolved as I bit into my doughnut and the intensity of the moment of consummation exploded to fill my consciousness entirely. In that first bite, there was the delicate nutty flavour of the outside mingling with the feathery sponge of the inside and then both of these mixed with the rush of delicious custard. It wasn’t too sweet, and the texture of the sponge was ideally contrasted with both the sugary exterior and the creamy custard interior.

Then I woke, as if from a dream, the world came back to me and I realised my face and hands were covered in sugar. Now I understand what all the fuss was about. Now I know, this is what doughnuts should be like!

[youtube XVdNs8cNcj4 nolink]

Visit Justin’s bakery – Bread Ahead (Bakery & Baking School), Cathedral St, SE1, with Borough Market Stall from Monday to Saturday

Read some of my other stories about Justin Gellatly

Night in the Bakery at St John

Visit The Secret Gardens of Spitalfields

Rodney Archer’s garden in Fournier St

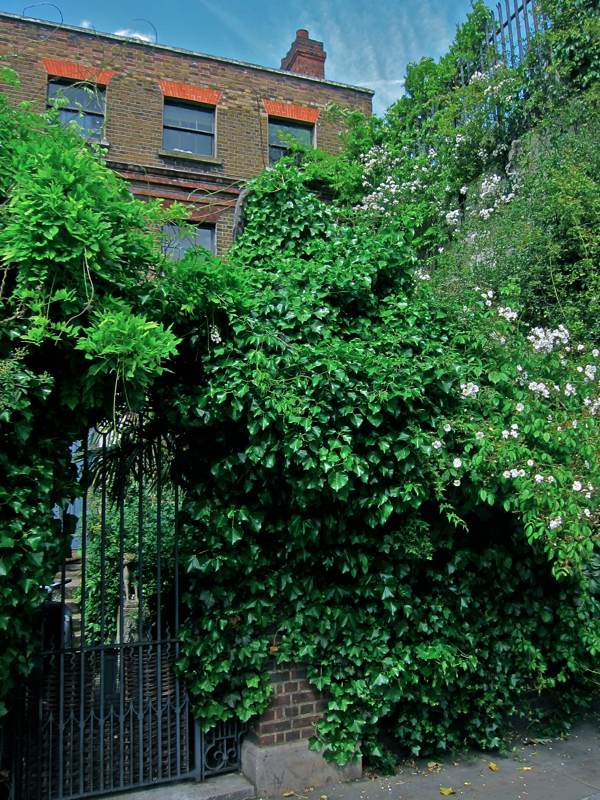

With the gracious permission of the owners, on Saturday 7th June from 10am until 4pm, you are invited to visit these hidden enclaves of green that are entirely concealed from the street by the houses in front and the tall walls that enclose them.

If you did not know of the existence of these gardens, you might think Spitalfields was an entirely urban place with barely a leaf in sight, but in fact every terrace conceals a string of verdant little gardens and yards filled with plants and trees that defy the dusty streets beyond.

Please support this opening in aid of charity – tickets cost £12 to visit all six gardens in Spitalfields and you can find out more on the website of the National Gardens Scheme

In Fournier St

In Princelet St

An architect’s garden in Wilkes St

Luis Buitrago, gardener in Fournier St

Rodney Archer’s cat

You may also like to read about

Mr Pussy’s New Game

My old cat, Mr Pussy, loves water. While others detest getting their feet wet, he has never been discouraged by rain, even delighting to roll in the wet grass. Consequently, when he languishes in hot weather, I commonly sponge him down with cold water – an ecstatic experience that leaves him swooning.

Although I am conscientious to leave him a daily dish of fresh water beside his bowl of dry biscuits, he prefers to drink rain water or running water, seeking out puddles, ponds and dripping taps. Sometimes when I have been soaking in the bath, he has even appeared – leaping nimbly onto the rim – and craned his long neck down and extended his pink tongue to lap up my bath water, licking his lips afterwards out of curiosity at the tangy, soapy flavour. And when I choose to stand in the bath and take a shower, he likes to jump in as I jump out to lap up the last rivulets before they vanish down the drain.

One day, I took the shower-head and left it lying upon the floor of the bath, switching on the water briefly to wash away the soap in order to leave him clean water to drink. Thus a new era began. He perched upon the rim of the bath, his eyes widening in fascination at the surge of water bouncing off the sides of the tub in criss-crossing currents. This element introduced a whole new level of interest for him and now it has become a custom, that I switch on the shower for a couple of seconds, so that he may leap onto the bath and manoeuvre himself down to lick up the racing trails before they disappear.

It was something I did occasionally to indulge him, then daily, and now he demands it whenever he sees me in proximity – perhaps a dozen times yesterday and sometimes in the middle of the night too. The game begins with the spectacle of the surge of water coursing around the bath. He gets pretty excited watching the rush. And then, as soon as the water is switched off, he lets himself down head first, leaving his back legs on the rim and moving swiftly to slurp up the rivulets as they run. Each time it is a different challenge and the combination of the necessity of quick thinking, of nimble gymnastics and the opportunity of refreshment is compelling for him.

In the winter – you will recall – I found myself letting him in and out of the drawing room door, as he sought respite from the warmth and then re-admission again five minutes later. I am aware of his controlling nature and the pleasure he draws in extricating these favours from me, yet this new game has become a compulsion for him in its own right. When it gives him such euphoria, I cannot refuse his shrill requests, trilling liking a song bird and indicating the bathroom with a deliberate twist of his neck.

From the moment I turn my steps in that direction he is ahead of me, leaping up and composing his thoughts upon the brink with the intensity of a diver before a contest. Hyper-alert when I switch on the tap momentarily, he is rapt by the sensory overload of the multiple spiralling streams of water and intricate possibilities for intervention. Running all the decisions in his mind, he may even make a move before the water is switched off. Unafraid to soak his feet, he places two paws down into the swirling current and starts to lap it up fast. Observing his skill and engagement as a credulous yet critical spectator of his sport, I cannot deny he is getting better at negotiating the bathtub and the runnels. His technique is definitely improving with practice.

Within a minute, the water has drained to trickles and, before I may rediscover my own purpose, he seeks a repeat performance of his new game – and thus, with these foolish pastimes, we spend our days and nights in the empty house in Spitalfields.

You may also like to read

Mr Pussy Gives his First Interview

and take a look at

The Cats of Spitalfields (Part One)

A Walk Down The Mile End Rd

William Booth points the way

It was once the custom for East Enders to promenade along the Mile End Rd at weekends, dressed in their Sunday best and admiring the shop windows, and – in similar vein – I set out down the road with my camera yesterday to record some of the sights for you.

Mile End Rd takes its name from the turnpike in Whitechapel, which stood exactly a mile from the City of London situated at the crossroads where Cambridge Heath Rd meets the Whitechapel Rd. Traders who had come far, bringing their goods to market in the City, would pass through this gate and park their wagons safely upon the wide thoroughfare, spending the night at one of the taverns in Whitechapel, before rising early to arrive in London next morning.

Beyond Whitechapel, lies Mile End Waste where William Booth preached against the degradations of drink in the nineteenth century, giving sermons which led to the founding of the Salvation Army to minister to the poor and destitute that congregated here – and, more than a century later, the Salvation Army still maintains Booth House in Whitechapel to fulfil the same purpose. Yet Booth’s statue by George E. Wade of 1927 stands outside Trinity Green Almshouses of 1695 for “decay’d Masters & Commanders,” revealing an earlier history of this area defined by the proximity to the London Docks.

Just across the road, is the site of Captain’s Cook’s House dating from the eighteenth century, when the land was open upon either side of the Mile End Rd and the masts of ships might been seen by travellers approaching London. Further east, the magnificent terrace built by Anthony Ireland in 1717 and Malplaquet House built by Thomas Andrews in 1741-2, along with equally affluent dwellings on Stepney Green attest to the wealth of those who made their money through maritime trade. Elsewhere, Bellevue Place, Maria Terrace and Mile End Place are more modest dwellings which survive as dignified examples of housing for those employed in local industries, brewery workers and artisans.

Remarkably these fragmentary survivals still hold their own amongst the dense nineteenth and twentieth century developments – accelerated by bombing and slum clearance and now the incursion of the City – and thus the entire history of the East End is to be found along the Mile End Rd.

The Albion Brewery, Whitechapel

Trinity Green Almshouses beside Park House, built c.1820 by the Barnes family, property developers

On this site stood Captain’s Cook’s house, demolished in the fifties and commemorated in the seventies

The former Wickhams Department Store, constructed 1927

In Bellevue Place, cottages once attached to the Charrington Brewery

The much-missed Billy Bunter’s Tea Stall

Genesis Cinema, built 1939, replacing Frank Matcham’s Paragon Theatre of 1885

Terrace built by Anthony Ireland in 1717

Nineteenth-century cottage in Stepney Green

Eighteenth century terrace in Stepney Green

Built in Stepney Green c.1694 for Dormer Sheppherd, a wealthy merchant with overseas connections and acquired c.1714 by Dame Mary Gayer, widow of East India Company’s Governor of Bombay

Malplaquet House, constructed by Thomas Andrews in 1741-2

Stepney Green Station by C.A. Brereton, 1902

Gothic Cottages in Maria Terrace

Eric Gill’s relief sculpture on the front of the New People’s Palace, 1936

The People’s Palace, built 1886-92

Looking west along the Mile End Rd

You may also like to look at

Old Girls Of The Central Foundation School

Writer Linda Wilkinson, ex-School Captain and celebrated author of two books about Columbia Rd, went along with Contributing Photographer Patricia Niven to this year’s Central Foundation School for Girls Reunion to do these interviews and portraits of the Old Girls.

Millie Rich, 1929-1934

I left in 1934 to go to St Martins School of Art. I loved the school, it was very different then to the attitudes that prevail now. You were very respectful of the teachers, you always stood up when they entered the room. We did Latin with Miss Green who married one of the governors. Many of the girls were from the East End and were first generation English, so you inhabited two cultures and, in order to survive, you spoke in one way at the school and in another way at home. Life was a lot less socially comfortable for us than it is today.

Shula Rich (known as Ruth at school), Millie Rich’s daughter

I always wanted to go to the Central Foundation School because my mother and my father both went there (the boy’s school is in Cowper St). In addition, it closed at 3pm whereas every other school closed at 4pm, so I could go home like a City worker. I would sit on the train back to Balham reading my Evening Standard.

Later we moved to Ilford. On public transport you had to wear your beret, but I had a great big bee-hive and was part of a girl gang – we folded our berets in half and pinned them with two clips behind our hair. Whenever a teacher caught us on the tube and told us we weren’t wearing our berets, we could say “Oh yes we are,” and we’d show them the back of our heads. After school, we could either go and talk to the market men – which was a great treat – or somehow go into Dirty Dick’s to do some pulling.

Patsy Butt (née Felt), 1963-1968

We had a fabulous uniform – gaberdine macs with red lining in the hood, so that everyone knew you were a Spital Sq girl. I loved the friends, loved the teachers. The fact that, having grown up in an area where you didn’t realise you could own your own home and that bathrooms were inside the house, to be tutored into a world where you could join in with anybody and anything – What can you say about an education that does that for you? Fabulous!

Nadjie Butler (née Huseyin), 1971-1977

There are so many memories it is hard to pick a special one, but the most fun I had was doing the sports and the sports days, and going down to the playing fields at Buckhurst Hill. I remember laughing a lot and making some really good friends and enjoying my education here. It gave me the ability to look forward in life. Not only giving me the foundation to have a long and successful employment, but also it taught me a really good lot of manners and morals that I have taken through my life.

Sandra Smith (née Foster), 1971-1977

My main claim to fame was that I did a solo performance in a concert for the late Richard Beckinsdale. One of the girls we were at school with was the daughter of his manager, so he came along to the school to hear us. We had a very good day. The school was a great place – what a great education we had! A lot of the friends I made then I have kept in touch with over the years.

Carol Salmon (née Foster), 1973-1979

I remember as a first year doing cross country running at Buckhurst Hill, and I remember falling into a ditch and being completely covered in mud. I ended up having to go home wearing another girl’s knickers as I didn’t have a spare pair. God I was so embarrassed! The school certainly gave me the tools for life – in the end I became a Police Officer.

Doreen Golding (née Jackson), 1953

Doreen returned to the East End having moved to Redbridge during WWII where she briefly attended Beale Grammar School. After her father died in an accident, her mother and their family came back to the East End. As Central Foundation School was the local grammar school, Doreen’s mother came knocking assuming that her daughter would just get in.

I had been out of education for six months because, when my father died, mum had pulled us all out of school whilst she decided what to do next. Also the standard here (at Central Foundation School) was so much higher than my school in Redbridge. I was told if I wanted to get in, I would have to sit another exam. That is my first recollection of this school, of sitting in the sixth form taking an exam with all the big girls standing around me. I started here in 1953 and it was a wonderful school. My old grammar school had a brown uniform and the headmistress here at the time was very kind. She told me and mum that, as my uniform was virtually new, I could wear it until it wore out. So there I sat, a splodge of brown in a sea of bottle green.

Lydia Shine (née Andrews), 1953-1959

I was not terribly academic but I enjoyed my time here, I found it very stimulating. The teaching we had was above excellent, and it has left me wanting to seek knowledge and made me interested in life, in things, people, history and literature – all the things that somehow get missed these days. After school, I started teacher training but I found it wasn’t for me. Then I went into the Civil Service and worked in the Law Courts for a while. I got married, had a family and then worked in office jobs etc. I also went into care work and have found a lot of fulfilment in that. In retrospect, I think I should have been a nurse.

In latter life, I found a big interest in music which I think probably stemmed from Central Foundation School. I have sung in various choirs, some of them quite prestigious so that has really become a big part of my life.

Christine Beesley (née Andrews), 1957-1964

Maureen Modica (née Franks), 1953-1959

It was like ‘The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie,’ very much so. If you weren’t going to be university fodder, forget it. To get married and have a family, or anything mundane like that, was for the lower echelons.

I didn’t go to university but exploited being a linguist and the only way that I could do that was on the continental telephone exchange and then in various foreign banks. The languages I speak are French, German and Italian. I can get by in Spanish. If you were in the A form – as I was – Latin was obligatory and French for almost everybody, but because I wanted to do German I had to wait until I was in the sixth form and do a crash course.

I never had a cookery lesson. When I got married ,I had no idea why potatoes, meat and veg all put on at the same time didn’t work. At first, I used to say to my husband, “Can’t we go out?” He said, “Not forever!”

Sandra Dryer (née McKay), 1954

I was a terrible teenager, I did nothing at school. I wasted my time there but, when I was forty, I went to study. I did a degree, went on to do a Masters, and I tutored at a Sixth Form College where I became the Head of the Department of Theatre Arts.

Elspeth Parris, 1967-1972

The school was a very good place for me to have gone to. I really did need the Headmistress, especially Mrs Dunford’s attitude to people, but educationally – in terms of academic stuff – it wasn’t actually that good for me. I was very much science-based and in those days it was assumed that if you were going to a good university, and I had the scholarship to go to a good university, that you had Latin. You had to have Latin to get into Oxford or Cambridge. Latin was a direct clash in the timetable with Physics, so I couldn’t do Physics. I eventually did Physics totally from scratch at university as a mature student.

However, the attitude to us as people – for a child as troubled as I was – was really what I needed. It gave me the chance at some kind of self-esteem. But academically, it really didn’t work for me. I eventually got to university much, much later and did Maths when I was thirty but my health collapsed and I wasn’t able to finish it. But the school’s ethos, that people matter, brought me back and I went on and did Social Work at university. Then, about four years ago, I trained for the church to be a Lay Minister within the Church in Wales. I eventually got a degree from the Open University. Currently, due to ill health I am unable to work, so have decided to lead a very simply life which gives me time to reflect on how I may serve the world, something I have always wanted to do.

Lesley Young (née Pratt), 1969-1974, wearing her school scarf, beret and badges

Pat Baker (née Vanderstenn), 1952-1958

I loved school but I hated my junior school in East Ham because the teacher wouldn’t mark my work as I didn’t have very nice handwriting. At Central Foundation School, nobody took any notice of that. I stayed on and went into the secretarial sixth form with Miss Heath, the first year she was at the school. She was good, she got us all jobs. She sent us to an employment agency off Moorgate where she knew the lady who owned it. We all got a job from that. Eventually, I worked at BP and I loved it there.

Gillian Weinberg (née Taler)

Jacky Chase (née Francom), 1971-1978

The things I remember most are the things they took us out to do – all the extracurricular activities, like the sport. I remember getting on the coach to go out to Buckhurst Hill for athletics and to the pool for swimming. The fact that, even though we were in the middle of a big city, they made provision for you was amazing.

Then the school trips – I remember going to Switzerland skiing and that was the first time I had ever been out of the country. To go with school friends, and teachers, and the have such a fabulous time was wonderful. To be able to experience other cultures and to be able to use some of our French, which we never thought we would have been able to do.

It was just everything that went with it, an all-round education – it wasn’t just academic stuff, it was everything else that we had the chance to see and do. We were taken to ballets, theatre and the opera. The chance to experience all that was just brilliant.

Joanne Veness, 1971-1976

I left just before my fifteenth birthday having taken my O levels and thinking that I had everything I needed to know about the world. I realise that I was very privileged to have had the education that I did. I didn’t make the most of it though. I remember most the camaraderie that we girls had, which continues on to this day. We still meet every three months or so and all the memories come out. If you’ve forgotten, there is someone who reminds you. Things like the big green knickers we wore for sports and being sick at the end of having tried to run the 800 metres. I am delighted and privileged to have gone to the school.

Miss Audrey Leary (Teacher of French, Spanish and a little bit of History for Nellie Holt)

I came to London from Ipswich in the early sixties. My History wasn’t very good, but I decided to do the Norman period and thought it would be a wonderful idea if the girls did a newspaper about the landing of the Normans. It was an absolutely awful idea but Nellie the Head of History let me do it – this would have been in 1961.

I went with the school when it went it moved in 1975. Elaine (Dunford) did a fabulous job of combining the two schools and we, the staff, got on so well together that it was a good experience all around. I was very apprehensive about coming today. I thought nobody would remember me and I wouldn’t recognise anybody, but one girl said, “Come over here and sit with us.” You were a lovely bunch of girls.

(Note: Miss Nellie Holt was a beloved Head of History, she was clever, funny and – true to say – a little eccentric.)

Reunion of 2014

In the Prefect’s Room , Christmas 1958

16th September, 1966

In the Prefect’s Room, Christmas 1958

Letter from Headmistress Elaine Dunford to a pupil upon the death of their mother

Bev, Sue & George in the Prefect’s Room, Christmas, 1958

Photo taken on the day of the closing of Central Foundation School in Spital Sq 1975

Photographs copyright © Patricia Niven

The Bishopsgate Institute is collecting a digital archive of memorabilia from Central Foundation School for Girls. If you have photographs, reports, magazines or any other material that the Institute can copy for the archive, please contact the Archivist Stefan.Dickers@bishopsgate.org.uk

You may also like to read about

At The Central Foundation School for Girls in Spital Sq

The First Reunion of the Central Foundation School for Girls

You may recall last year it was my delight to collaborate with Beryl Happe in staging the first reunion of the Central School Foundation School for Girls at their former School Hall in Spital Sq which now houses the Galvin Restaurant.

This year there was also a Service of Thanksgiving at St Botolph’s, Bishishopsgate, and the tea party swelled from sixty to ninety guests with a long waiting list too. Today, writer Linda Wilkinson, ex-School Captain and celebrated author of two books about Columbia Rd, recalls her memories of Spital Sq. She and Contributing Photographer Patricia Niven went along to the reunion to create a series of portraits and interviews with the Old Girls that we will be publishing tomorrow.

Reunion of 2014 (Click to enlarge)

I had been away from Bethnal Green for twelve years when I moved back in 1986. One day on a walk through Spitalfields, I came across the shell of what was left of my old School Hall. Some things set in your mind as immutable, such was Central Foundation School for Girls. I went away and read about the valiant fight that had taken place to save the building but – as over the years it fell further into decrepitude – I felt something more should be done.

Some friends ran a drinks company, and we thought that we might buy it and turn it into a restaurant – so we contacted the agent who was handling the building and went to visit. Where the trampoline once stood, pigeons droppings had created their own strange artwork. The fabric of the roof was only kept watertight with a tarpaulin and the proud marble pillars were scratched and damaged – but the hole where I had managed to throw a shot put through the dais was still there.

We had no resources to take on such a task, so I walked away convinced that the bulldozers would finally remove all trace of it. Then, in 2009, a sign appeared stating that a restaurant was due to open there and I was delighted. There was a website so, being an Old Girl of the Central Foundation School and former School Captain, I wrote and offered to open the restaurant for them. A polite email from Sara Galvin of the restaurant management, asking me to write an article for their magazine about the school, firmly put me in my place.

I wrote my recollections and I got invited to the launch of the restaurant in my old School Hall. What I had not mentioned in my article was the ethos of the place and the staff, led by the headmistress Mrs Dunford – because we had a fabulous education there. I can say that Central Foundation School changed my life completely.

Yet my mother and father had been very chary of my desire to go to Spital Sq, as it was known locally. At the pre-entry interview with the Headmistress, my mother was frosty when she was quizzed as to my suitability to attend. On being asked what the problem was she said, “It’ll worry her brain. All that learning.”

Mother was politely asked to sit outside.

“Well, Linda dear,” Elaine Dunford said, “And what do you think?”

My brain survived.

RECOLLECTIONS OF CENTRAL FOUNDATION SCHOOL by Linda Wilkinson

Grace Crack was like the rest of us, a bright kid from London’s East End, with one exceptional quality – she utterly loathed going to school. One day before a Bank Holiday, she rammed the ball cock in the main tank of the school wide open. How she had managed to climb into the loft space was never revealed, but we imagine Grace had accomplices.

When the housekeepers returned to open up after the break they were met by a torrent of water. The school was comprehensively flooded, and this being a Grammar School, and if my memory serves me correctly, Grace was similarly comprehensively expelled.

At one time, it was a fee paying school and by the mid-twentieth century it still retained a few students whom, we were told, were private pupils. I cannot vouch for this but some of the girls commuted from as far away as Orpington in Kent so I imagine it was true.

The rest of us were a motley bunch. Many were Costermongers’ daughters from the almost-exclusively Jewish markets that peppered the area. The biggest of those of course was Spitalfields Fruit & Vegetable Market, then on our very doorstep. In summer, the smell of rotting vegetables perfumed the air. In winter, tramps settled around bonfires on the almost derelict Spital Sq. It was eerie to come across this Dickensian aspect of London when the swinging sixties was at its height.

Our teachers were a mixture of bright young things, the first real batch of the post-war generation and the old guard. All of this was overseen by the elegant and free spirited headmistress, Elaine Dunford, a wonderful teacher both of English and of life itself.

The old guard had some notables, amongst them Miss Jenkins. She was a brogue and tweed wearing harridan in her sixties who taught biology. She told us that she and her brother were two of the products of human breeding experiments between the Huxleys and Darwins. If so, eccentricity was their main product but she was also a great teacher and could bring science alive in a way I have seldom come across since.

Miss Russell (“roll the ‘R’ dear”) was rumoured to be Bertrand Russell’s sister. She took on the task of removing our glottal stops with true brio. Elocution was not something most of us had bargained for when we got into the school. We all knew we had to do Latin, which I loathed almost as much as Grace had hated school, but standing on a table reciting “I am a little Christmas Tree,” when I was the chubbiest in the class never filled me with glee. Even if turning us ‘Gels’ into ladies was a bit more of a trial than Miss Russell had expected, she never wavered. Yet, later in life, when public speaking became part of my life, I was more than grateful to that tiny bird-like woman whom at the age of fourteen I found faintly ridiculous.

Ranged on the other side of the staff room were the Communists. To a woman, the younger teachers espoused a red philosophy. No more so than when the 1968 Paris riots erupted and a good few of them upped and went over to join in. At the start of the next new term, we were encouraged to stand and applaud as they processed down the Hall with their bandages and plaster casts worn for all to see, like a political version of ‘Chariots of Fire’.

I shall never forget the poor plumber who came to unblock the drain beneath the sink in the caretaker’s utility room and was seen running screaming from the school with Mr Reeves, the caretaker, in hot pursuit carrying a human skull. “Come back, it’s bound to be Roman,” he cried. The school was built on a Roman burial site.

It was a fun and sometimes challenging schooling. I sometimes wonder how the present day doyens of education would react to a history lesson being halted whilst the teacher told us of yet another failed attempt to have sex the night before. It certainly beat Alexander the Great or the Punic Wars as a topic.

So our Hall is now a restaurant, a fitting use for a place that has seen a lot of life, fun and laughter over the years. It is a shame that Old Girl Georgia Brown (Lilian Klopf), who was the first ever Nancy in Lionel Bart’s ‘Oliver!’ is not alive to entertain us there.

As for Grace Crack, she was rumoured to have emigrated.

The Bishopsgate Institute is collecting a digital archive of memorabilia from Central Foundation School for Girls. If you have photographs, reports, magazines or any other material that the Institute can copy for the archive, please contact the Archivist Stefan.Dickers@bishopsgate.org.uk

You may also like to read about

The First Reunion of the Central Foundation School for Girls