At Oxgate Farm

The quaint timbered dwelling with gables and a roughcast exterior manifests the idyll of domesticity for many and, as testimony to its potency, suburban streets up and down the country are lined with approximations to this notion in varying degrees of authenticity. Yet in a suburb north of Cricklewood, among the acres of development which spread across the land during the twentieth century, stands just such a house that is the embodiment of the romantic retreat, only this example dates from 1465 and it is not the result of architectural whimsy but a rare survival from another age.

Five miles up the Edgware Rd, where it becomes a dual carriageway, you turn left and walk up Oxgate Lane through the light industrial estate built upon the Oxgate farmlands laid out in 1285. At the crossroads, you turn right into Coles Hill Rd, described by B W Dexter in ‘Cricklewood Old & New ‘ in 1908 as having “all the charm of an untouched rural pathway with luxurious hedgerows and many varieties of wild flowers.” These days, it might be characterised as unremitting suburbia if it were not for the presence of Oxgate Farm, still asserting itself, undeterred by the changes that time has wrought.

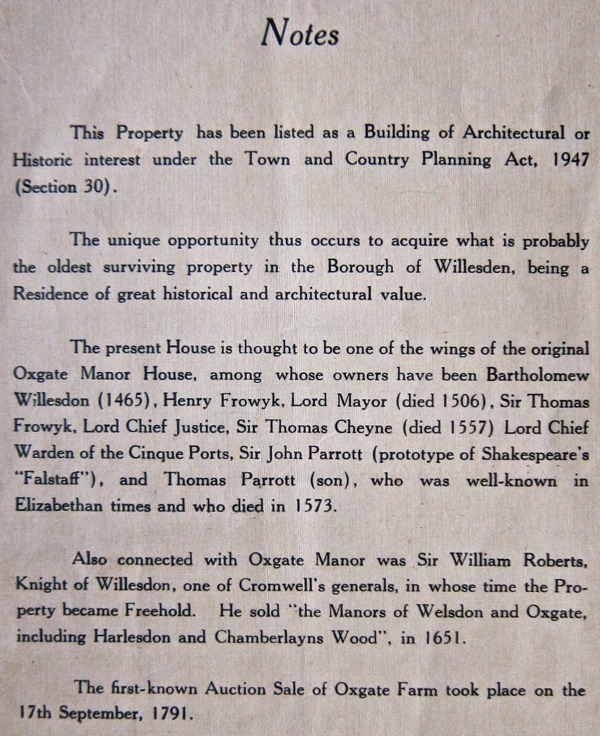

Still roofed with its handmade tiles and floored with ancient worn flags, this is the oldest house in the Borough. Originally one of the eight Prebendal manors of St Paul’s Cathedral, the surviving building is believed to be a wing of the fifteenth century manor house, which was occupied in 1465 by Bartholomew Willesden, collector of the King’s taxes, and in 1500 by Henry Frowk, Lord Mayor. Elizabeth I’s half-brother, Lord Chief Warden of the Cinque Ports, Sir John Parrott, also lived here – he is best remembered today as the prototype for Shakespeare’s character of Falstaff.

Over the centuries, the manor reduced in size from a thousand acres until just the house and back garden are left today today. In the second half of the twentieth century, it was home to the painter Marie Burtwhistle and then Shakespearian actor Mark Dignam and his wife Virginia, who cherished the house for its romance. But now, two years after Virginia’s death, Oxgate Farm has reached an impasse in its existence. At the beginning of the twentieth century brick footings were installed that have subsided, removing support for the timber frame structure so that, in some cases, the joists no longer meet the exterior walls and bedroom floors lurch at alarming angles. Shored up with scaffolding props and recently refused support by English Heritage, the property is too costly for the current owners to repair.

Like a great old galleon cast up by a tidal wave to sit in the beach car park surrounded by modern vehicles, Oxgate Farm languishes today, yet it is an historically important and irresistibly charismatic building that cannot be allowed just to fall down.

Former residents Bartholomew Willesden of Oxgate and his wife portrayed in brasses of 1492

The humped ridge of the roof

Numbers upon the joists made by fifteenth century joiners to ensure the frame fits together correctly

An eighteenth century indenture to lease Oxgang Farm

Thomas Powell bought the property in 1751

Holes in the door, so the farmer could check his livestock from the parlour when the kitchen was a byre

Nineteenth century residents at the south door

The south door today

The farm is to be seen on the left in this late nineteenth century photo

The south entrance photographed in 1968

Nineteenth century wallpaper revealed in the bathroom

Shakespearian actor Mark Dignam & his wife Virginia bought the house in 1968

Mark Dignam’s study, untouched since he died

The south side of the house is held up by scaffolding props at present

The brick wall is collapsing forward at the front of the house

Oxgate Farm and shop in 1968

Ghost Signs Of Stoke Newington

This is the epicentre of ghost sign activity in Stoke Newington Church St. On the left is a triple-layer painted wall of the Westminster Gazette, Criterion Matches and Gillette Razors – all merged into one glorious palimpsest – and on the right is a double layer painted sign advertising “Fount Pens Repaired.”

Sam Roberts was walking past one day in 2006 when he had a moment of inspiration. “I thought that’s neat, nowadays we just have disposable pens,” he admitted to me, “The sign was from a different world to ours.” As Sam’s fascination grew, he began to compile a map London’s ghost signs and cycled around to photograph them all. Recognising that these curious signs comprise a powerful element in the collective psyche of urban life, he approached the History of Advertising Trust to develop an online archive containing more than six hundred specimens of which he is now the curator.

Recently, Sam has been studying the ghost signs of Stoke Newington, researching the stories behind their creation. The people and the businesses are mostly gone long ago and these fading signs are their last vestiges on this earth. Yet not everyone shares Sam’s recognition of their importance, as the painting-out of a huge intricate ghost sign upon the wall above above Stoke Newington Post Office demonstrated recently.“Many of these signs are over a hundred and twenty-five years old, “ Sam explained, “if they were a pieces of jewellery or furniture, people would immediately recognise their value.”

Thus, Sam is now leading walking tours to tell the poignant and compelling stories of the signs, revealing a local perspective upon the history of the streets and ensuring that these fragile traces of former generations are appreciated for their beauty and significance, as signposts to our shared past.

In Northwold Rd: R. Ellis. Ironmonger. Stoves, Range & Bath Boiler Works. Gas Fitter & Plumber. General House Repairs. Est. 60 Years. – Robert Ellis was born in 1835, died in 1898 and was buried across the road in Abney Park Cemetery. Note usage of bricks to define the height of the letters.

On Cazenove Rd: F. Cooper, Job Master for Wedding Carriages, Broughams, Landaus, Cabs

The faded illustration on the ceramic panel is captioned “The Duchess of Devonshire canvasses the Jolly Butchers to vote for Fox in 1784”

Eloma Preparations was here in Carnham St from 1947 until the eighties

Richardson & Sons, Shirtmakers, Hackney, Leyton & Walthamstow – painted in 1955 on an older panel

On Stoke Newington High St, painted over an earlier indecipherable sign: John Hawkins & Sons, Cotton Spinners & Manufacturers, Preston, Lancashire (Painted between 1926-1939 when the company was concentrating on increasing their home market when the struggle for Indian independence took away their overseas trade)

Walker Bros, Fount Pen Specialists, Phone Dalston 4522, Agents for Watermans Ideal Fountain Pen (A sponsored sign dated to the early twenties and repainted later on the left with “Any make” added.)

Hurstleigh’s Bakery – Daren – Brown Bread (Daren flour mills were in Dartford, Kent, on the banks of the river Darent)

Alf the Purse King – A Rubinsten & Sons – Purses, Pouches, Handbags, Wallets

In Stoke Newington Church St : Crane, House Decorator, Plumber, Gas & Hot Water Fitter, Contractor for General Repairs (Dating from 1890, this believed to be Stoke Newington’s oldest ghost sign.)

Visible from Stoke Newington Station, a narrow fragment of a double layer sign advertising “6 Tables”, “A Speciality” and “Debossing”

Find out more about Sam Roberts’ tours at his Ghost Signs website or visit the History of Advertising Ghost Signs Archive

You may also like to read about

At Fulham Palace

You leave Putney Bridge Station, cross the road, enter the park by the river and go through a gate in a high wall to find yourself in a beautiful vegetable garden with an elaborate tudor gate. Beyond the tudor gate lies Fulham Palace, presenting an implacable classically-proportioned facade to you across a wide expanse of lawn bordered by tall old trees. You dare to walk across the grass and sneak around to the back of the stately home where you discover a massive tudor gateway with ancient doors, leading to a courtyard with a fountain dancing and a grand entrance where Queen Elizabeth I once walked in. It was only a short walk from the tube but already you are in another world.

For over a thousand years the Bishops of London lived here until 1975 when it was handed over to the public. But even when Bishop Waldhere (693-c.705) acquired Fulham Manor around the year 700, it was just the most recent dwelling upon a site beside the Thames that had already been in constant habitation since Neolithic times. Our own St Dunstan, who built the first church in Stepney in 952, became Bishop of London in 957 and lived here. By 1392, a document recorded the great ditch that enclosed the thirty-six acres of Britain’s largest medieval moated dwelling.

Time has accreted innumerable layers and the visitor encounters a rich palimpsest of history, here at one of London’s earliest powerhouses. You stand in the tudor courtyard admiring its rich diamond-patterned brickwork and the lofty tower entrance, all girded with a fragrant border of lavender at this time of year. Behind this sits the Georgian extension, presenting another face to the wide lawn. Yet even this addition evolved from Palladian in 1752 to Strawberry Hill Gothick in 1766, before losing its fanciful crenellations and towers devised by Stiff Leadbetter to arrive at a piously austere elevation, which it maintains to this day, in 1818.

Among the ecclesiastical incumbents were a number of botanically-inclined bishops whose legacy lives on in the grounds, manifest in noteworthy trees and the restored glasshouses where exotic fruits were grown for presentation to the monarch. In the sixteenth century, Bishop Grindal (1559-1570) sent grapes annually to Elizabeth I, and “The vines at Fulham were of that goodness and perfection beyond others” wrote John Strype. As Head of the Church in the American Colonies, Bishop Henry Compton (1675-1753), sent missionaries to collect seeds and cuttings and, in his thirty-eight tenure, he cultivated a greater variety of trees and shrubs than had previously been seen in any garden in England – including the first magnolia in Europe.

At this time of year, the newly-planted walled garden proposes the focus of popular attention with its lush vegetable beds interwoven with cosmos, nasturtiums, sweet peas and french marigolds. A magnificent wisteria of more than a century’s growth shelters an intricate knot garden facing a curved glasshouse, following the line of a mellow old wall, where cucumber, melons and tomatoes and aubergines are ripening.

The place is a sheer wonder and a rare peaceful green refuge at the heart of the city – and everyone can visit for free .

Cucumbers in the glasshouse

Melon in the glasshouse

Five hundred year old Holme Oak

Coachman’s House by William Butterfield

Lodge House in the Gothick style believed to have been designed by Lady Hooley c. 1815

Tudor buildings in the foreground with nineteenth century additions towards the rear.

Sixteenth century gate with original oak doors

The courtyard entrance

Looking back to the fountain

Entrance to the medieval hall where Elizabeth I dined

Chapel by William Butterfield

Tudor gables

All Saints, Fulham seen from the walled garden

Freshly harvested carrots and vegetable marrows

Ancient yews preside at All Saints Fulham

Visit Fulham Palace website for opening times and details of events – admission is free

Tiles By William Godwin Of Lugwardine

There is spot where my eyes fall as I enter the house between the front door and the foot of the stair, where I always felt there was something missing and it was only when I visited Bow Church this spring to admire C R Ashbee’s restoration work that I realised there would once have been floor tiles in my entrance way. It was a notion enforced when I noticed some medieval encaustic tiles at Charterhouse and began to research the possible nature of the missing tiles from my house.

In 1852, William Godwin began creating gothic tiles by the encaustic process century at his factory at Lugwardine in Herefordshire and became one of the leading manufacturers in the nineteenth century, supplying the demand for churches, railway stations, schools, municipal buildings and umpteen suburban villas. Inevitably, some of these tiles have broken over the time and millions have been thrown out as demolition and the desire for modernity have escalated.

So I decided to create a floor with the odd tiles that no-one else wants, bringing together tiles that once belonged to whole floors of matching design, now destroyed, and give them a new home in my house. Oftentimes, I bought broken or chipped ones and paid very little for each one – but I hope you will agree that together their effect is magnificent.

Encaustic tiled floor designed by C R Ashbee for Bow Church using Godwin tiles

Medieval encaustic tiles at the bricked-up entrance to Charterhouse in Smithfield

You may also like to read about

At Hyper Japan

On Saturday, Earls Court was teeming with manga characters – from fairies to steam-punks and schoolgirls to super-heroes. There were those with pointy ears, there were those with tails and plenty with primary-coloured hair. Some were ferocious and other were funny, yet they all shared a sense of joy in the Japanese art of dressing up extravagantly and embodying your fantasy in public that is known as ‘cosplay.’ Hyper Japan promises video games, pop music, sushi, samurai swords, bonsai, comics, and more – but it was the costumed characters in their glory that stole the day.

The last day of Hyper Japan 2014 is at Earls Court today from 9:30am until 6:00pm

Charles Hindley’s Cries Of London

The most recent acquisition in my Cries of London collection is a second edition of Charles Hindley’s ‘History of the Cries of London, Ancient & Modern’ from 1884. My predecessor had the same idea to collect images of the Cries and trace their development over time and, in his book, he reprints many wood blocks from earlier chapbooks, including the set below. Originally just the size of a thumbnail, these anonymous finely-observed prints evoke the circumstance and demeanour of hawkers and pedlars in early-nineteenth century London with startling economy of means.

The Rabbit Man – Buy my rabbits! Rabbits, who’ll buy? Rabbit! Rabbit Who will buy?

New Cockles – Buy my cockles! Fine new cockles! Cockles fine and cockles new!

Banbury Cakes – Buy my nice and new Banbury Cakes! Buy my nice new Banbury Cakes, O!

Mulberries – Mulberries, all ripe and fresh today! Only a groat a pottle – full to the bottom!

Capers, Anchovies – Buy my capers! Buy my nice capers! Buy my anchovies! Buy my nice anchovies!

Lavender – Buy my lavender! Sweet blooming lavender! Sweet blooming lavender! Blooming lavender!

Mackerel – Live mackerel! Three a-shilling, O! Le’ping alive, O! Three a-shilling,O!

Shirt Buttons – Buy my shirt buttons! Shirt buttons! Buy shirt buttons! Buttons!

The Herb Wife – Buy rue! Buy sage! Buy mint! Buy rue, sage and mint, a farthing a bunch!

The Tinker – Maids, I mend old pots and kettles! Mend old pots and kettles, O!

Buy fine flounders! Fine dabs! – All alive, O! Fine dabs! Fine live flounders, O!

You may also like to take a look at these other sets of the Cries of London I have collected

More John Player’s Cries of London

More Samuel Pepys’ Cries of London

Geoffrey Fletcher’s Pavement Pounders

William Craig Marshall’s Itinerant Traders

H.W.Petherick’s London Characters

John Thomson’s Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana II

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana III

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

James McBarron of Hoxton

James McBarron

When I published Bob Mazzer’s Underground photographs from the seventies and eighties, I was astonished by how many readers got in touch to name people in the pictures, but I never expected it to happen when I published Horace Warner’s photographs of the Spitalfields Nippers from around 1900. Yet Lynne Ellis wrote to say her father James McBarron recognised Celia Compton whom Horace Warner photographed at the age of fifteen in 1901. By the time James knew Celia, as a child in the thirties, she was Mrs Hayday and he encountered her as a money-lender when he was sent to make the weekly repayments on his mother’s loans.

Intrigued by this unexpected connection to a photograph of more than a century ago, I took the train from Fenchurch St down to Stanford Le Hope recently to meet James McBarron and learn more of his story. This is what he told me.

“I am from Hoxton, Shoreditch, I was born in George Sq at the back of Hoxton Sq – it’s not there anymore. There were seven tenements and another building where Mrs Hayday lived, all around a yard with a lamppost in the middle. We attached a rope onto the lamppost and swung on it. We used to have a bonfire there in November and all the families came along. It was like a village and a lot of people were related, and everyone knew each other. We were clannish and there were quite a few families with members in different flats – my grandmother and grandfather lived there in one flat and I had two aunts in another.

Eighty years later I can still remember Mrs Hayday, even though I was only seven, eight or nine at the time. It was in 1936 or thereabouts. She was a money-lender and I was sent by my mother every Sunday to pay sixpence to her, but it didn’t mean anything to me at the time. To my eyes, as young boy, she was overwhelming. I was shown into the bedroom by her daughter and she was always lying there in bed. She took out a book from the bedside and made a note of the money. I recall an impression of crisp white sheets and she had dyed blonde hair. She was a buxom woman, a little blowsy. She smelled of scent – Phul Nana by Grossmith – the only scent I knew as a young boy, the factory was in Newgate St. I was awestruck because she was so unlike any of the other people I knew. There was a never a man there or a Mr Hayday. She was a very nice lady, she said, ‘Hello’ and ‘Say ‘Hello’ to your mum and dad.’ And that was Mrs Hayday.

My father, George, was a carpenter from Sunderland and he served in the Great War. My mother worked at Tom Smith’s Cracker Factory in Old St. My parents met in London and my mother’s family already lived in George Sq. My grandfather, he was an inventor and I admired him very much. He made a little working steam engine, and he tapped the gas main and had a tube with a little flame, so he could light his roll-ups. He played the violin and read music, and he never went to work. My gran used to go round to the pub for a jug of beer and they’d all go upstairs to my grandparents’ flat and play darts, and he’d play the violin.

We kids used to chop firewood to make money. The boys and girls used to go around collecting tea-chests and packing-boxes from the back of all the furniture factories, and say ‘Can we take it away, Mister?’ We chopped it up into sticks and made bundles, and we’d sell them for a penny or a ha-penny. We used to go to Spitalfields Market and ask for ‘Any spunks?’ or ‘Spunky oranges and apples?’ and they’d chuck the fruit that was going bad to us.

We didn’t think we were poor, except there was a family called Laban who were better off than us. He was a bookmaker and had touts. I remember their son had a jacket with pleats in the back and I wanted one like it, but when my mum eventually got me one it wasn’t so good. My father had a blue serge suit and it was pawned each Monday to pay the rent and bought back each Friday when he got paid. On Sundays, we went down to Stephenson’s Bakery in Curtain Rd to get a penny loaf.

When you came out of George Sq, there was a little alleyway leading through to Hoxton Market. There was Marcus the Newsagent, and next to it was Pollock’s and they had toy theatres in the window and these glass bottles with coloured liquid – it was a tiny shop. Next to that was Neville’s where my father bought our boots and shoes. I can remember every shop in the Market. Hoxton St was different then, bustling with stalls and there were barrows selling roasted chestnuts and boiled sheep’s heads.

William was the eldest child in our family, then I was born, then Peter, then Johnny and last of all Margaret. There was twenty-one years between us and she was born while I was away in the army, so she didn’t know me when I came back. I knocked them up at seven in the morning and called, ‘Here’s your boy, back again!’ We had three rooms – two bedrooms and a living room, and that’s why we had to move.

After the war, they moved us up to Haggerston to a new building in Stean St and George Sq was demolished because it was a slum. Everything broke up when people moved out. They took out all our furniture – including a table and chest of drawers my father made – and put it in a closed van and fumigated it because of the bugs. I’ve still got his tool box. It was a ragtag and bobtail existence, but I think we were a little better off than some. “

Celia Compton photographed at age fifteen by Horace Warner in 1901. Years later in 1936, a year after her husband died and when James McBarron was a child, she lived at 5e George Sq and he knew her by her married name of Celia Hayday.

James McBarron with his father’s carpentry box

Margaret & George McBarron in Haggerston

James and his brother Peter

As a boy, James visited Benjamin Pollock’s Toy Theatre shop at 208 Hoxton Old Town

James’ younger brother Johnny in the new flat when the family were rehoused in Stean St, Haggerston, in 1946

James’ elder brother William at the piano

James & June McBarron

James & June McBarron got married in St Leonard’s Shoreditch on 5th June 1954 and celebrated their diamond wedding this summer

James McBarron, 1965

James catches mackerel on holiday in Devon

James & June McBarron’s children, Lynne & Ian, in the sixties

You may also like to read these other Hoxton stories

Joseph Markovitch, I’ve live in Hoxton for eight-six and a half years