At Lucy Sparrow’s Felt Corner Shop

Lucy Sparrow

In 1993, there was Rachel Whiteread’s ‘House’ sculpture in Grove Rd, then Tracey Emin & Sarah Lucas’ ‘Shop’ in Bethnal Green Rd and now Lucy Sparrow’s ‘Corner Shop’ in Wellington Row. Each of these endeavours has succeeded in capturing the public imagination in different ways, as reflections upon the traditional East End landscape of terraced housing and small independently-run shops – and, in her witty and deceptively-ambitious creation, Lucy Sparrow proves herself a worthy successor to her illustrious predecessors.

For several years, I have been walking past the melancholy empty dry-cleaners in Wellington Row on my way to Columbia Rd, so it was a joy to return this week with Contributing Photographer Patricia Niven and find the place humming with life. As her most ambitious project to date, artist Lucy Sparrow has stitched the entire contents of a corner shop, down the minutest detail, in felt and the collective effect is quite overwhelming and beautiful.

Upon arrival, there is an infectious atmosphere of collective celebration as visitors delight in discovering familiar items of grocery recreated in felt and wonder at how these everyday things have been rendered strange and exotic. It is both a dreamlike vision of the world transformed into textiles and a poignant elegy for a culture that is passing away – as our corner shops, which once provided important social spaces for local communities, are closed or replaced by soulless and exploitative chains.

“I have been making things with felt since I was nine, that’s twenty years, and my first job, at fourteen years old, was in a corner shop,” Lucy admitted. Once she said this, the dramatic literalism of her endeavour became apparent, because this is the result of seven months labour on Lucy’s part, working fourteen hours a day to sew more than four thousand items by hand. It is touching when you recognise favourite purchases, whether chocolate bars, packets of cigarettes or cans of soup stitched so affectionately, and it unlocks a personal nostalgia, recalling your own emotional memories that are bound up with these modest objects.

So convincing is Lucy’s needlework that, a few times each day, customers arrive without realising they are entering an art installation and, even as I stood talking with her, someone came in and asked to buy a bottle of water. “We’ve got as far as me putting the box of cigarettes on the counter before they realised,” Lucy confided to me, “That was a proud moment!”

Locals make their own felt groceries at one of Lucy’s workshops

Lucy Sparrow with Saturday Boy Bradley Garrett and Shop Assistant Rachel-Anne Read

Photographs copyright © Patricia Niven

The Corner Shop is open at 19 Wellington Row E2 7BB, until 31st August from 10am – 7pm

You may also like to take a look at

The Corner Shops of Spitalfields

Viscountess Boudica & The Tricity Contessa

“its been a moving exsperance for me”

As you can see, Viscountess Boudica of Bethnal Green is in heaven. She has found the Tricity Contessa 643 electric cooker that she has been searching for since 1978. For Marcel Proust it was madeleines, for Charles Foster Kane it was Rosebud, but for Viscountess Boudica it was the Tricity Contessa. She has been yearning for it for the last forty years – as the key to unlock her past – and, now that her quest is fulfilled, the temps perdu have been regained in Bethnal Green.

Viscountess Boudica wrote to me to convey the happy news and revealed in her own words how the Tricity 643 first entered her life – “the orridginall tricity 643 was brought from a shop in the village back in 1961 and my mother said she’d only had it a couple of days when on the 6th of November – a Monday I think – it was at one o five in the morning, she went into labour on the kitchen table in the cottage and I was born and slid off the table and hit my head on the tricity cooker then I was rushed to hospital. talk about taking a bunn out of the oven.”

Naturally, I was curious to learn more of the mystical allure of this seemingly mundane domestic appliance, so I paid the Viscountess a visit and she confided to me the childhood psychological drama surrounding the Tricity Contessa 643.

“What happened was that, when I was five years old, me and my mother went to live in one of two properties in Lynam belonging to my Aunt Mabel who lived nearby in Shipton. It was an old dilapidated bungalow. On this particular day, Mabel was supposed to take me to school because my mother had to leave early that morning. And Mabel brought Susie with her, the daughter of her son, who was a spoilt brat of five years old. Mabel doted on Susie.

I can remember that day as if it was yesterday. It was about a quarter to eight and I’d had no breakfast, so my aunt said, ‘You can have a fried egg.’ She put the pan on the cooker with some lard in it but then Susie started playing up and Mabel had to leave. She said to me, ‘When it’s done, turn it over. You’ll know when it’s done when it starts to burn.’ So she left with Susie.

Then the egg started to spit and it caught me in the eye. I felt this pain in my eye. As a child, the kitchen seemed large to me, and I had to stand on a chair to do the washing up or even to put the light on. So I stood on a chair to reach the cooker. I managed to turn off ring number three but my hand slipped and I fell off the chair onto the cardinal red floor.

All I remember is waking up next to the frying pan with the egg all over the place congealed on the floor and I had a terrible headache. When I saw my aunt Mabel a few days later, I told her what had happened. ‘You stupid boy, you should have been more careful,’ she said, ‘but at least you’ve learnt to cook now which will stand you in good stead on the farm.’ And I thought, ‘You old bag!’ She told me it would be stupid to tell my mum and I managed to get the floor cleaned. For a few years, I had a mark in my eye, and it left me with a fear of frying pans and frying.

As the years went by, we moved around to different places and eventually we moved into prison quarters in Chelmsford and the Tricity 643 was put in storage. My new stepfather, David, was a prison warder who used to play cards with the Krays. Eventually, the Tricity Contessa was given away because only gas cookers were permitted on prison property.

So, in 1978, I decided I needed to find the Tricity 643 again. I went round to all the secondhand dealers and put an advert in the Essex Chronicle. I wanted to get back to that day in 1963 to relive the events and change the outcome. It was terrible that my mother went off and left me, and my aunt shouldn’t have left me either. It was a kind of pain that I hadn’t experienced before, and I was afraid that the place would catch fire and I’d be trapped in it.

When I went to all the secondhand dealers, looking for a Tricity 643, they said, ‘We’ll get you one next week, why not take a look at this other one now?’ Although I got distracted, I was determined never to give up even though I met some unscrupulous characters and if I hadn’t met them my life would have been different. As time went on, I broadened my search and people brought old cookers to me from as far as Bradford until I had three sheds full. They were all different models and half of them were no good.

Then, three weeks ago, I was looking online as I always do and I thought, ‘Can I be bothered to scroll through the thousands of cookers?’ – and then I saw it, and it came from Guildford! It was nine days until the sale, so I emailed the seller to make an offer but he said, ‘No,’ and I had to bid in the auction. It was going quickly and other people were bidding on it, but I won with a bid of thirty-six pounds. It cost me fifty pounds to get it delivered. I’ve cleaned it but I haven’t plugged it in yet.

It has been a long and arduous journey, and a lot of deception and lies from those devious secondhand dealers. But I have relived the events of that day and laid my feelings to rest, and I am peaceful now. I shall always keep the Tricity Contessa 643. I’m going to use it and fry eggs. They say, ‘Everything comes to she who waits.’“

Yet this is not quite the end of collecting domestic appliances for Viscountess Boudica because, this week, she also took delivery of a Moffatt electric cooker from 1900 that now sits proudly in her living room. Thus, like all true quests the seeker found not just the object of the quest but also acquired something else of value along the way – since Viscountess Boudica has gathered London’s best private collection of vintage domestic appliances, all of which she has restored herself. It was the necessity of seeking the Tricity Contessa 643 that led Boudica to them, discovering unexpected joys and enriching her life with a passion for these wonderful old contraptions that no-one else loves.

Viscountess Boudica as a child

The fabled Tricity Contessa 643 of 1961

Viscountesss Boudica’s drawing of the Tricity 643 from memory

Viscountess Boudica faces up to her fear of frying

Boudica’s new Tricity Contessa came with its original instruction manual

Vicountess Boudica’s other new acquisition

The Moffatt Electric Cooker of 1900 – “It’s survived two world wars!”

You may also like to read about

Viscountess Boudica’s Domestic Appliances

Viscountess Boudica’s Halloween

Viscountess Boudica’s Christmas

Viscountess Boudica’s Valentine’s Day

Viscountess Boudica’s St Patrick’s Day

Viscountess Boudica Goes Cornish

Read my original profile of Mark Petty, Trendsetter

and take a look at Mark Petty’s Multicoloured Coats

Benjamin Shapiro Of Quaker St

Ben Shapiro

In the East End, you are constantly reminded of the people who have left and of the countless thousands who never settled but for whom the place only offered a contingent existence at best, as a staging post on their journey to a better life elsewhere. Ben Shapiro has lived much of his life outside this country, since he left as a youth with his family to go to America where they found the healthier existence they sought, and escaped the racism and poor housing of the East End. Yet now, in later life, after working for many years as a social worker and living in several different continents, he has chosen to return to the country of his formative experience. “I’ve discovered I like England,” he admitted to me simply, almost surprised by his own words.

“I was born in the London Hospital, Whitechapel, in 1934. My mother, Rebecca, was born in Manchester but her parents came from Romania and my father, Isaac (known as Jack), was born in Odessa. He left to go to Austria and met my mother in Belgium. He was a German soldier in World War I and, in 1930, he come to London and worked as a cook and kosher caterer. I discovered that immediately after the war, he went to Ellis Island but he was sent home. In the War, he had been a radio operator whose lungs had been damaged by gas. He spoke four or five languages and became a chef, cooking in expensive hotels and it was from him I learnt never to sign a contract, that a man’s word is his bond. He had an unconscionable temper and by today’s standards we would be called abused children. I once asked my mother if she would leave him and she said, ‘Where would I go with three children?’ I have a younger brother, Charles, who lives in New York now and a younger sister, Frieda, who died three years ago in Los Angeles.

My parents lived in a flat in Brick Lane opposite the Mayfair Cinema, until they got bombed out in World War II. We got bombed out three times. My first school was the Jewish Free School, I went to it until I was four and the war broke out when I was five. My father was in Brick Lane when Mosley tried to march through in 1936 and the Battle of Cable St happened. He remembered throwing bricks at the police. When the war broke, we became luggage tag children and one of my earliest memories was travelling on a train with hundreds of other children to Wales. We lived with a coal miner’s family and, at four or five, he would come home covered in coal dust. His wife would prepare a tin bath of hot water and he would sit in it and she would wash him clean, and then we could all have supper.

Me and my brother were sent back to London when the Blitz was in full swing, but my sister stayed in Aylesbury for the entire duration of the war and the family wanted to adopt her. When I returned with her fifty years later, she met the daughter of the family, her ‘step-sister’ – for the first time since then – and they recognised each other immediately, and fell into each other’s arms.

In London, the four of us lived in a two bedroom flat and my brother and I slept together in one bed. My parents talked Yiddish but they never taught me. In the raids, we took shelter in Whitechapel Underground but my father would never go. He said, ‘I’ve been through one war – if I’m going to die, I’ll die in my bed.’ My father gave me sixpence once to go and see ‘For Whom The Bell Tolls’ at the cinema, but we got to the steps just as the siren sounded and I waited thirty years to see that film.

Then I was sent off again, evacuated to a Jewish family in Liverpool. On the train there, I met a boy and we decided to ask to be billeted together. We were eight or nine years old and we slept together and, every night, he wet the bed. So we had to hang out our mattress and pyjamas every day to dry them, they didn’t get washed just dried. Once Liverpool became a target for bombing, I got sent home again. After the war, he contacted me and said, he’d had an operation to correct his bladder.

I have distant memories of being sent away again to the countryside, to Ely. When we got to the village green at Haddenham, a man came up to me and asked, ‘Are you Jewish’ and I said, ‘No’ so he said, ‘You can come and live with me then.’ All the children in the school knew I was Jewish and asked ‘Where’s your horns?‘ but I was well cared for and didn’t want to leave in the end. My father never visited or wrote letters, I think it was because he had been in World War I and he was familiar with death, and he could have been killed in the Blitz at any time. If he died, I would have stayed. We were always well fed and I have a theory that my father sent them Black Market food.

Towards end of the war, we were housed by London County Council in Cookham Buildings on the Boundary Estate. I remember looking out of the window and seeing German planes coming overhead. There was flat that was turned into a shelter but we all realised that it would not protect us and, if a bomb dropped, we should all be killed. Above us, there was an obese woman with two children and she never got to the shelter before the all clear sounded.

Our flat was damp due to bomb damage and I caught Rheumatic Fever, and was admitted to the Mildmay Mission Hospital and was at death’s door for two months, and then sent to Greyshall Manor, a convalescent home. After that, we qualified for rehousing and we were the first tenants to move into the newly-built Wheler House in Quaker St in 1949. It was comfortable and centrally heated and we had a bathroom. From there, at fourteen years old, I went to Deal St School. It was where I first experienced racial intimidation and bullying, so I told the teacher and he said, ‘You’re a Jew, aren’t you?’ Eventually, I became Head Prefect, which gave me carte blanche to discipline the other pupils.

During the years at Wheler House, I became friendly with the bottling girls from the Truman Bewery who walked past at six in the morning and six at night. I knew some of the Draymen too and they let me feed the horses. Soon after we moved in, my father wouldn’t give me any pocket money, he said, ‘You’ve got to earn it.’ I went down Brick Lane and enquired at a couple of stalls for a job and I had a strong voice, so a trader said, ‘I need a barker,’ and, for about a year, I became a barker each weekend in Petticoat Lane, crying ‘Get your lovely toys here!’ I was opposite the plate man who threw crockery in the air and next to the chicken plucker.

I worked in the City of London as a junior clerk in Gracechurch St, near the Monument, but I feel – if I had stayed – I would still be junior clerk.

The lady next door, she had a friend from America and she sponsored my brother to go there. So then we all wanted to go and, on June 6th 1953, we went down to Southampton and took a boat to New York and then travelled to Los Angeles. It was for health reasons. My mother had been unwell and my father said it would be a better life, which it turned out to be. I was seventeen years old.”

c.1900, Odessa – My father Isaac is sitting in the centre, he was born around 1896 and left in 1906 during the last great pogrom to go to Vienna

c. 1920, London – My mother Rebecca is on the right with her sister on the left. Her parents were known as Yetta & Maurice

Ben on the left, aged seventeen years old, photographed with his family on the boat going to a new life in America in 1953

Ben and his family were the first people to move into this flat in Wheler House, Quaker St, when the building was newly completed in 1949

East End Soldiers Of World War One

In the week of the centenary of the outbreak of World War I, I have compiled these biographies of just a handful of the thousands of those from the East End who served in the conflict. These photographs are selected from those gathered by Tower Hamlets Community Housing for their exhibition which runs until 29th August at 285 Commercial Rd.

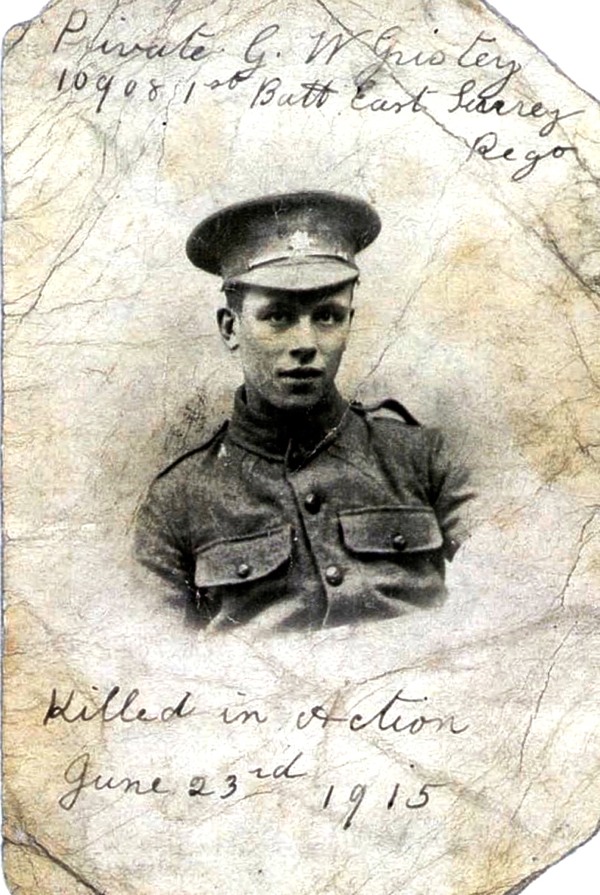

George Gristey was born in Hackney on 13th March 1890. At the time of his death his mother, Laura, lived in Cranbrook Rd, Green St, Bethnal Green. George served as a Private in the East Surrey Regiment and was was killed in action in Belgium on 23rd June 1915 and buried at Woods Cemetery, south-east of Ypres in West Flanders.

Arthur Outram was born on 20th September 1890 in London St, Ratcliff and died in Belgium on 10th October 1917 while serving as a Sergeant with the Second Battalion, Duke of Wellington’s Regiment. Like many of his comrades, he has no known grave, but is commemorated on panel eighty-two of the Tyne Cot Memorial in the Tyne Cot Cemetery (the largest British war cemetery) south-west of Passchendaele, and his name is also upon the memorial at St Anne’s, Limehouse. He married Ellen Callaghan at St Matthew’s, Limehouse, on 26th November 1916 and they had one son, also called Arthur, who was less than a month old when his father was killed.

Issy Smith VC (pictured on the left) was born as Ishroulch Shmeilowitz in Alexandria, Egypt, on September 1890, the son of French citizens Moses and Eva Shmeilowitz, who were of Russian origin. Issy arrived in the East End aged eleven, as a stowaway, and attended Berner St School, Commercial Rd, before working as a delivery man locally. He joined the British Army in 1904 and was present at the Delhi Durbar of King George V and Queen Mary in 1911.

The citation for Issy Smith’s Victoria Cross reads “No. 168 Acting Corporal Issy Smith, 1st Battalion, The Manchester Regiment. For most conspicuous bravery on 26th April, 1915, near Ypres, when he left his Company on his own initiative and went well forward towards the enemy’s position to assist a severely-wounded man, whom he carried a distance of two hundred and fifty yards into safety, whilst exposed the whole time to heavy machine-gun and rifle fire. Subsequently Corporal Smith displayed great gallantry, when the casualties were very heavy, in voluntarily assisting to bring in many more wounded men throughout the day, and attending to them with the greatest devotion to duty regardless of personal risk.”

In recognition of his Victoria Cross, he was also awarded the French Croix de Guerre and Russian Cross of St. George. He died on 11th September 1940.

Henry Sumner was born on 27th April 1875 in Dingle Lane, Poplar. Henry was a professional soldier – a Corporal in the Tenth County of London Regiment who served in the Boer War and the First World War, when he became a guard at the German Prisoner-of-War camp at Alexandra Palace. He married Margaret Fenn (1882-1958) at St Saviour’s, Poplar, on 7th October 1904 and they had eight children. He died at the Queen’s Hospital for Military Personnel in Chislehurst, Kent, in 1924.

Joseph Klein (1888-1974) lived in Gold St, Mile End Old Town, and he never spoke of the conflict in which he was awarded the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal and the Victory Medal in World War I – It is believed he threw them all in the Thames.

Richard Williams was born as William Waghorn on 4th April 1875 in Old Brewery, Hayes, Kent. He worked in Kent as a labourer and moved to the East End to work on the construction of the Blackwall Tunnel. He married Margaret Constable (1888-1966) on 28th June 1913 in the Registry Office in Mile End Old Town and they had twelve children and lived all their married life in Stepney. Richard enlisted for World War I but his lungs were damaged in the conflict, causing him to suffer from poor health until he died in Stepney in 1947.

Poet and artist, Isaac Rosenberg, who died in action at the Somme in 1918 at the age of twenty-seven, lived at 47 Cable St between 1897 and 1900 where he attended St Paul’s School, St George’s-in-the-East. In 1900, the family moved over to Stepney so Isaac could attend Baker St School and receive a Jewish education.

Isaac loathed war and hated the idea of killing but, while unemployed, he learned that his mother would be able to claim a separation allowance, so he enlisted. He was assigned to the Twelfth Suffolk Regiment, a Bantam Battalion formed of men less than five foot and three inches in height, but in the spring of 1916 he was transferred to the Eleventh Battalion of the King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment and in June of that year he was sent to France.

He was killed early on the morning of 1st April 1918 during the German spring offensive. His body was not immediately found but, in 1926, the remains of eleven soldiers of the KORL were discovered and buried together in Northumberland Cemetery, Fampoux. Although his body could not be identified, he was known to be among them. His remains were later reinterred at Bailleul Road East Cemetery, St. Laurent-Blangy, near Arras where his headstone reads ‘Buried near this spot.’ Beneath his name, dates and regiment, are engraved the Star of David and the words “Artist and Poet.”

His ‘Poems from the Trenches” are recognised as some of the most outstanding verse written during the War.

Samuel Adelson who resided with his aunt at 8 Gosset Street, Brick Lane was in the Thirty-Eighth Battalion, Royal Fusilliers, and fought in Palestine in 1918. He was born in Nemajunai, Trakai, Lithuania in 1896 to David Adelson and Zlota Gordon Adelson. After the war, in 1920 Samuel emigrated to America where he died in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1925.

Charles Hunt was born in 1888 in Mile End and served as a Private in the Twelfth (Prince of Wales’ Royal) Lancers. The Lancers arrived in France on 18th August 1914 and only ten days later, fought a battle against a regiment of German Dragoons at Moy. Charles was awarded the 1914 Star and Victory medals but, just eleven days after arriving in France and at only twenty-six years of age, he died of his wounds – Charles’ grave is in Bavay, a small cemetery that was behind German lines for most of the war.

George Outram was born on 17th March 1870 in Dunstan Rd, Mile End, the son of Arthur Outram (1826-1904) and Martha Jane Harden (1841-1877). He married Margaret (Mag) Charlotte Constable (1871-1932) on Christmas Day 1889 at St Paul’s Church, Bow Common, which stood on the site of the modern St Paul’s with St Luke’s Church, at the junction of Burdett Rd and St Paul’s Way. After service in the Merchant Navy, George became a lighterman, and he and Mag had ten children. The picture shows George in an army uniform, taken during the World War I, when he took barges across to France. Although not enlisted in the army, he wore a uniform so that if captured by the Germans he would not be shot as a spy. He died in Mile End Hospital in April 1938, aged sixty-eight.

Henry Maffia and Elizabeth Maffia with their son John, taken in 1915. Henry was wounded twice in Flanders and gassed on the last day of the War, dying on 16th March 1920 from the effects of the gas. Liberal MP for Bethnal Green, Sir Percy Holman, fought until 1928 to obtain a War Widows’ Pension for Elizabeth Maffia.

Robert Tolliday (front row first left) lived in Peabody Buildings, Shadwell. He served in the Twelfth Lancers until 12th May 1917 when the Lancers became the Fifth SMG and he stayed with them until the end of the War. He was one of the last who charged into the German lines on horseback with no weapon beyond a wooden lance and when a bomb exploded beneath his horse, Old Tom, it kept on running with its entrails streaming until it collapsed.

George Joseph Dubock was descended from a Huguenot family that arrived in the East End in 1706. He was born on 5th December 1878 in 109 Eastfield St, Limehouse, and his family moved shortly after to Mile End Old Town. George worked as a Dock Labourer and a Road Sweeper/Scavenger for the Council. Serving as Private #14373 in the Sixth Dorset Regiment, George was a victim of a gas attack and suffered post-traumatic stress after the War. Later, George became a Master Cabinet Maker and ended his days working in Newbury, restoring old furniture until he died in 1951.

Cards sent home from the Front by George Joseph Dubock

Alfred William Blanford was born in Poplar in 1894 and lived in Whitethorn St, Bow. At eighteen, in April 1912, he married Florence Jenkins and, in the December of the same year, they had their first child – also called Alfred. In February 2014, Alfred & Florence’s second son, Fredrick, was born and their third child, Edith, in December 1916.

Alfred joined the Army before his twentieth birthday and, in December 1914, by the time of Fredrick’s birth, he was in training in Aldershot. He served as a Driver in the Royal Field Artillery and was killed in action in May 1916, before the birth of his daughter Edith.

Henry George Crooney, also known as Harry, was born in Poplar in 1897 and served in the Royal Artillery from 1914-1918. Lying about his age, Henry enlisted in the Army before he was legally eligible. He joined the Royal Artillery because of his experience with horses, having worked since a child with his father who ran horses and carts from the docks.

Henry’s grand-daughter, Cheryl Loughnane, recalls the wartime stories Henry would tell – including his hatred of bully beef and of the time he stole a pig from a French farm.

After the war, Henry married Annie and worked as a haulier. When he retired, he could not stop driving around the East End and became a volunteer for ‘Meals on Wheels,’ delivering dinners to pensioners.

Alfred James Barwell was a Private in the Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent Regiment). He lived with his parents, Alfred & Alice Barwell, at 27 Museum Buildings, Chester St, Bethnal Green. Aged just nineteen, Alfred was killed in action on 21st March 1918. His is listed on the Pozieres Memorial (Panel Ref 58 and 59) in the Somme.

James Polston, Rifleman 5059 in the Eighteenth Battallion London Regiment – London Irish Rifles. James was born on 20th September 1884, the eldest son of James & Elizabeth Polston who lived at Warner Place, Bethnal Green, and Lauriston Rd in Bow. He was killed in action on 8th December 1916 and is commemorated at the Railway Dugouts Burial Ground in Flanders.

(Photo of Water Tull courtesy of Doug Banks)

Second Lieutenant Walter Tull was the first black British Army Infantry Officer. The son of a joiner, Walter was born in Folkestone on 28th April 1888. His father, the son of a slave, had arrived from Barbados in 1876. In 1895, when Walter was seven, his mother died and his father remarried only to die two years later. The stepmother was unable to cope with all six children and so Walter and his brother Edward were sent to a Methodist -run orphanage in Bethnal Green.

Walter was a keen footballer and played for a team in Clapton. In 1908, his talents were discovered by a scout from Tottenham Hotspur and the club decided to sign the promising young footballer. He played for Tottenham until 1910, when he was transferred for a large fee to Northampton Town. Walter became the first black outfield player to play professional football in Britain.

When World War I broke out, Walter abandoned his football career to join the Seventeenth (First Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment and, during his military training, he was promoted three times. In November 1914, as Lance Sergeant, he was sent to Les Ciseaux but, in May 1915, he was sent home with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Returning to France in September 1916, Walter fought in the Battle of the Somme between October and November. His courage and abilities encouraged his superior officers to recommend him as an Officer and, on 26th December, 1916, Walter went back to England to train as an Officer.

There were military laws forbidding ‘any negro or person of colour’ being commissioned as an Officer. Despite this, Walter was promoted to Lieutenant in 1917 and became the first ever black Officer in the British Army, and the first black Officer to lead white men into battle.

Walter was sent to the Italian Front where he twice led his Company across the River Piave on a raid and both times brought all of his troops back safely. He was mentioned in Despatches for his ‘gallantry and coolness’ under fire by his commanding officer and he was recommended for the Military Cross, but never received it.

After their time in Italy, Walter’s Battalion was transferred to the Somme and, on 25th March 1918, he was killed by machine gun fire while trying to help his men withdraw.

Walter was such a popular man that several of his men risked their own lives in an attempt to retrieve his body under heavy fire, but they were unsuccessful due to the enemy soldiers’ advance. His body was never found and he is one of the many thousands from World War I who has no known grave.

(Story & photo of John Arthur Tribe courtesy of East London Advertiser)

John Arthur Tribe was part of a large, close-knit family from Kirby St, Poplar. John lied about his age and joined the Army in 1911, serving in the Fourth Battalion, King’s Royal Rifle Corps, at first in India and then at the Battle of Loos in 1915, where he was killed in action. John is commemorated at the Loos Memorial but has no known grave.

The Working Lads Institute (now the Whitechapel Mission) founded by Rev Thomas Jackson, was the first shelter in London to offer refuge to black soldiers during World War One

The exhibition runs until 29th August on weekdays from 9:30 – 4:30pm at Tower Hamlets Community Housing, 285 Commercial Rd, E1 2PS

You might also like to read about

An East End Alphabet

Amandine Alessandra & Rute Nieto Ferreira see letters everywhere, and now they have channelled their witty insights into a nifty paperback published by Tower Block Books. Beautifully produced as a numbered limited edition, printed by risograph and including a map to set out in search of this idiosyncratic East End typography, THE BIG LETTER HUNT is a modest imaginative triumph.

Minstrel Court, Teesdale Close

Canalside gasworks viewed from Hackney Rd

Corner of Myrdle St & Fieldgate St

Dron House, Adelina Grove

201 Bishopsgate & the Broadgate Tower

Cranbrook Estate, Mace St

Central Foundation Girls’ School, Mile End Rd

Dorset Estate, Diss St

Myrdle Court, Myrdle St

Treadway St

Images copyright © Amandine Alessandra & Rute Nieto Ferreira

Click here to order your copy of THE BIG LETTER HUNT – copies will sent out shortly!

East End Suffragette Map

Coinciding with the East London Suffragette Festival, Researcher Vicky Stewart & Designer Adam Tuck have collaborated to bring you this map of some key events in the struggle for Women’s Suffrage that happened in the East End, centred around W F Arber & Co Ltd where Gary Arber’s grandmother Emily Arber was responsible for printing handbills for Sylvia Pankhurst upon the Golding Press in the basement at 459 Roman Rd.

Click to enlarge and see the map in the detail

The recent closure of W F Arber & Co Ltd, after one hundred and seventeen years, inspired me to look further at Gary Arber’s story of his grandmother, Emily Arber, organising the free printing of handbills and posters for the Suffragette movement. Just what was going on locally, who were involved, and how were these Suffragettes organised?

Nothing prepared me for what I discovered. My knowledge of Suffragette activity was limited to stories of upper middle class ladies marching behind Mrs Pankhurst, waving ‘Votes for Women’ banners, being imprisoned, getting force-fed, and then eventually securing the vote. In part this was true – Mrs Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel believed middle class women had the education and influence to bring about the necessary change, but Sylvia disagreed and insisted it was only direct action by working class women that could win the vote.

In 1912, Sylvia Pankhurst came to Bow as representative of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) to campaign for local MP George Lansbury, who had resigned his seat in parliament to fight a by-election on the issue of votes for women. Although Lansbury lost the election, he continued to support Sylvia who decided to stay in the East End and do everything in her power to carry on the fight – not only to champion the cause of Suffrage but also to challenge injustice and alleviate suffering wherever she could.

She opened her first WSPU Headquarters in Bow Rd in 1912 but moved to Roman Rd when forming the East London Federation, whose policy was to “combine large-scale public demonstrations with public militancy… [to attract] immediate arrest.”

In January 1914, Christabel asked Sylvia to change the name of the ELF and separate from the WSPU, and the organisation became the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELFS) with new headquarters in Old Ford Rd.

What amazes me about this story is the number of women – often with active support of husbands or sons – who, despite harsh poverty and large families, gave huge support to Sylvia and the campaign. They risked assault and often were beaten by policemen at rallies, on marches and at meetings. They risked being sent to Holloway and subjected to force-feeding. They risked the anger and abuse of those who did not support Women’s’ Suffrage.

So who were these women and what do we know of them? Below you can read extracts from Sylvia Pankhurst’s books, ‘The Suffragette Movement’ and ‘The Home Front’, which locate their actions in the East End.

– Vicky Stewart

6

Victoria Park “On Sunday, May 25th 1913, was held ‘Women’s May Day’ in East London. The Members of Bow, Bromley, Poplar, and neighbouring districts had prepared for it for many weeks past and had made hundreds of almond branches, which were carried in a great procession with purple, white and green flags, and caps of Liberty flaunting above them from the East India Dock gates by winding ways, to Victoria Park. A vast crowd of people – the biggest ever seen in East London – assembled ….. to hear the speakers from twenty platforms.”

12

288 Old Ford Rd was home to Israel Zangwill, political activist and strong supporter of Sylvia and the Suffragette movement.

13

304 Old Ford Rd was home to Mrs Fischer where meetings were held .

7

Old Ford Rd was the route taken by the Suffragettes May Day processions to Victoria Park when they met with violence from the police at the gates and suffered many injuries.

[youtube 08sOs5odCDM nolink]

8

400 Old Ford Rd became the third headquarters of the East London Federation of Suffragettes in 1914. A Women’s Hall was built on land behind which was used for a cost-price restaurant which provided nutritious meals for a pittance to women suffering from the huge rise in food prices in the early months of the war.

9

438 Old Ford Rd, The Mother’s Arms The ELFS set up another creche and baby clinic on this street, staffed by trained nurses and developed upon Montessori lines. This was housed in a converted pub called The Gunmaker’s Arms, whose name was changed to The Mother’s Arms.

1

Roman Rd “I decided to take the risk of opening a permanent East End headquarters in Bow … Miss Emerson and I went down there together one frosty Friday morning in February to hunt for an office. The sun was like a red ball in the misty, whitey-grey sky. Market stalls, covered with cheerful pink and yellow rhubarb, cabbages, oranges and all sorts of other interesting things, lined both sides of the narrow Roman Rd. ‘The Roman’ , as they call it, was crowded with busy kindly people. I had always liked Bow. That morning my heart warmed to it for ever.”

3

159 Roman Rd, (now 459) Arber & Co Ltd, Printing Works where Suffragette handbills were printed under the supervision of Emily Arber.

5

152 Roman Rd In 1912, tickets were available from this house, home of Mrs Margaret Mitchell, second-hand clothes dealer, for a demonstration in Bow Palace with Mrs Pankhurst and George Lansbury.

10 & 11

45 Norman Rd (now Norman Grove) A toy factory was opened in October 1914 to provide women with an income whilst their husbands were at War. They were paid a living wage and could put their children into the nursery further down the road.

4

Roman Rd Market The East London Federation of Suffragettes ran a stall in the market, decorated with posters and selling their newspaper, The Women’s Dreadnought – a “medium through which working women, however unlettered, might express themselves and find their interests defended.”

15

103 St Stephen’s Rd was home to George Lansbury and his family.

16

St Stephen’s Rd “On November 5th 1913, on my way to a Meeting to inaugurate the People’s Army, I happened to call at Mr Lansbury’s house in St Stephen’s Rd. The house was immediately surrounded by detectives and policemen and there seemed no possibility of mistake. But the people of Bow, on hearing of the trouble, came flocking out of the Baths where they had assembled. In the confusion that ensued the detectives dragged Miss Daisy Lansbury off in a taxi, and I went free.

When the police authorities realised their mistake, and learnt that I was actually speaking at the Baths, they sent hundreds of men to take me, but though they met the people in the Roman Rd as they came from the Meeting I escaped. Miss Emerson was again struck on the head, this time by a uniformed constable, and fell to the ground unconscious. Many other people were badly hurt. The people replied with spirit. Two mounted policemen were unhorsed and many others were disabled.”

19

28 Ford Rd “The members had begged me, if ever I should be imprisoned under the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’, to come down to them in the East End, in order that they might protect me, they would not let me be taken back to prison without a struggle as the others had been, they assured me.

On the night of my arrest Zelie Emerson had pressed into my hand an address: ‘Mr and Mrs Payne, 28 Ford Rd, Bow.’ Thither I was now driven in a taxi with two wardresses. As the cab slowed down perforce among the marketing throngs in the Roman Road, friends recognised me, and rushed to the roadway, cheering and waving their hands. Mrs Payne was waiting for me on the doorstep. It was a typical little East End house in a typical little street, the front door opening directly from the pavement, with not an inch of ground to withdraw its windows from the passers-by. I was welcomed by the kindest of kind people, shoemaking home-workers, who carried me in with the utmost tenderness.

They had put their double bed for me in the little front parlour on the ground floor next the street, and had tied up the door knocker. For three days they stopped their work that I might not be disturbed by the noise of their tools. Yet there was no quiet. The detectives, notified of my release, had arrived before me. A hostile crowd collected. A woman flung one of the clogs she wore at the wash-tub at a detectives head. The ‘Cats’, as a hundred angry voices called them, retired to the nearby public-houses, there were several of these havens within a stone’s throw, as there usually are in the East End.

Yet, even though the detectives were out of sight, people were constantly stopping before the house to discuss the Movement and my imprisonment. Children gathered, with prattling treble. If anyone called at the house, or a vehicle stopped before it, detectives at once came hastening forth, a storm of hostile voices. Here indeed was no peace. My hosts carried me upstairs to their own bedroom, at the back of the house, hastily prepared, a small room, longer but scarcely wider than a prison cell – my home when out of prison for many months to come. (…)

In that little room I slept, wrote, interviewed the Press and personalities of all sorts, and presently edited a weekly paper. Its walls were covered with a cheap, drab paper, with an etching of a ship in full sail, and two old fashioned colour prints of a little girl at her morning and evening prayers. From the window by my bed, I could see the steeple of St Stephen’s Church and the belfry of its school, a jumble of red-tiled roofs, darkened by smoke and age, the dull brick of the walls and the new whitewash of some of the backyards in the next street.

Our colours were nailed to the wall behind my bed, and a flag of purple, white and green was displayed from an opposite dwelling, where pots of scarlet geraniums hung on the whitewashed wall of the yard below, and a beautiful girl with smooth, dark hair and a white bodice would come out to delight my eyes in helping her mother at the wash-tub. The next yard was a fish curers’. An old lady with a chenille net on her grey hair would be passing in and out of the smoke-house, preparing the sawdust fires. A man with his shirt sleeves rolled up would be splitting herrings, and another hooking them on to rods balanced on boards and packing-cases, till the yard was filled, and gleamed with them like a coat of mail. Close by, tall sunflowers were growing, and garments of many colours hung out to dry. Next door to us they bred pigeons and cocks and hens, which cooed and crowed and clucked in the early hours. Two doors away a woman supported a paralysed husband and a number of young children by making shirts at 8d a dozen. Opposite, on the other side of Ford St, was a poor widow with a family of little ones. The detectives endeavoured to hire a room from her, that they might watch me unobserved. “It will be a small fortune to you while it lasts!” they told her. Bravely she refused with disdain, “Money wouldn’t do me any good if I was to hurt that young woman!” The same proposal was made and rejected at every house in Ford Rd.

Flowers and presents of all kinds were showered on me by kindly neighbours. One woman wrote to say that she did not see why I should ever go back to prison when every woman could buy a rolling pin for a penny.”

2

321 Roman Rd, Second Headquarters of the East London Federation “We decided to take a shop and house at 321 Roman Rd at a weekly rental of 14s 6d a week. It was the only shop to let in the road. The shop window was broken right across, and was only held together by putty. The landlord would not put in new glass, nor would he repair the many holes in the shop and passage flooring because he thought we would only stay a short time. But all such things have since been done.

Plenty of friends at once rallied round us. Women …. came in and scrubbed the floors and cleaned the windows. Mrs Wise, who kept the sweetshop next door, lent us a trestle table for a counter and helped us to put up purple, white and green flags. Her little boy took down the shutters for us every morning, and put them up each night, and her little girls often came in to sweep.”

20

Bow Rd – Sylvia described it as ‘dingy Bow Rd.’

25

The George Lansbury Memorial – Elected to parliament in 1910, he resigned his seat in 1912 to campaign for women’s suffrage, and was briefly imprisoned after publicly supporting militant action.

George Lansbury

26

The Minnie Lansbury Clock is at the Bow Rd near the junction with Alfred St. Minnie Lansbury was the daughter-in-law of George Lansbury, and very actively supported the campaign and was in Holloway. She died at the age of thirty-two.

Minnie Lansbury is congratulated on her way to be arrested at Poplar Town Hall

14

Bow Rd Police Station The police were horrifyingly brutal towards Suffragettes when on demonstrations and then, once arrested and tried, they would often receive excessively harsh prison sentences. Hunger striking was in protest against the government’s failure to treat them as political prisoners.

Mrs Parsons told Asquith – “We do protest when we go along in processions that suddenly without a word of warning we are pounced upon by detectives and bludgeoned and women are called names by cowardly detectives, when nobody is about. There was one old lady of seventy who was with us the other day, who was knocked to the ground and kicked. She is a shirtmaker and is forced to work on a machine and she has been in the most awful agony. These men are not fit to help rule the country while we have no say in the matter.” (From the Woman’s Dreadnought.)

Under the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’ hunger strikers were released when their lives was in danger so as to recuperate before returning to finish their sentences. They told tales of dreadful brutality during force-feeding in Holloway.

17 & 18

13 Tomlin’s Grove “When the procession turned out of Bow Rd into Tomlin’s Grove they found that the street lamps were not lighted and that a strong force of police were waiting in the dark before the house of Councillor Le Manquais. Just as the people at the head of the procession reached the house, the policemen closed around them and arrested Miss Emerson, Miss Godfrey and seven men, two of whom were not in the procession, but were going home to tea in the opposite direction.

At the same moment twenty mounted police came riding down upon the people from the far end of Tomlin’s Grove, and twenty more from the Bow Rd. The people were all unarmed. … There were cries and shrieks and people ran panic-stricken into the little front gardens of the houses in the Grove.

But wherever the people stopped the police hunted them away. I was told that an old woman who saw the police beating the people in her garden was so much upset that she fell down in a fit and died without regaining consciousness. A boy of eighteen was so brutally kicked and trampled on that he had to be carried to the infirmary for treatment. A publican who was passing was knocked down and kicked and one of his ribs was broken. Even the bandsmen were not spared. The police threw their instruments over the garden walls. The big drummer was knocked down and so badly used that he is still on the list for sick insurance benefit. Mr Atkinson, a labourer, was severely handled and was then arrested. In the charge room Inspector Potter was said to have blacked his eye.”

21

198 Bow Rd was the first Headquarters of the First Headquarters of the East London Federation, 1912. When Sylvia first arrived in Bow she rented an empty baker’s shop at 198 Bow Rd. She used a platform to paint “VOTES FOR WOMEN” in gold across the frontage and addressed the crowds from here.

22

The Obelisk, Bromley High St “On the following Monday, February 17th (1913) we held a meeting at the Obelisk, a mean-looking monument in a dreary, almost unlighted open space near Bow Church.

Our platform, a high, uncovered cart, was pitched against the dark wall of a dismal council school in the teeth of a bitter wind. Already a little knot of people had gathered; women holding their dark garments closely about them, shivering and talking of the cold, four or five police constables and a couple of Inspectors. We climbed into the cart and watched the crowd growing, the men and women turning from the footpaths to join the mass. … I said I knew it to be a hard thing for men and women to risk imprisonment in such a neighbourhood, where most of them were labouring under the steepest economic pressure, yet I pleaded for some of the women of Bow to join us in showing themselves prepared to make a sacrifice to secure enfranchisement …

… After it was over Mrs Watkins, Mrs Moore, Miss Annie Lansbury, and I broke an undertaker’s window. Willie Lansbury, George Lansbury’s eldest son, who had promised his wife to go to prison instead of her because she had tubercular tendencies and could not leave their little daughter only two years old, broke a window in the Bromley Public Hall.

I was seized by two policemen, three other women were seized. We were dragged, resisting, along the Bow Rd, the crowd cheering and running with us. We were sent to prison without an option of fine.

There were four others inside with me: Annie Lansbury and her brother Will, pale, delicate Mrs. Watkins, a widow struggling to maintain herself by sweated sewing-machine work, and young Mrs. Moore. A moment later little Zelie Emerson was bundled in, flushed and triumphant – she had broken the window of the Liberal Club.

That was the beginning of Militancy in East London. Miss Emerson, Mrs Watkins and I decided to do the hunger-strike, and hoped that we should soon be out to work again. But although Mrs Watkins was released after ten days, Miss Emerson and I were forcibly fed, and she was kept in for seven weeks although she had developed appendicitis, and I for five. When we were once free we found that we were too ill to do anything at all for some weeks.

But we need not have feared that the work would slacken without us. A tremendous flame of enthusiasm had burst forth in the East End. Great meetings were held, and during our imprisonment long processions marched eight times the six miles to cheer us in Holloway, and several times also to Brixton goal, where Mr Will Lansbury was imprisoned. The people of East London, with Miss Dalgleish to help them, certainly kept the purple, white and green flag flying …”

23

Bromley Public Hall, Bow Rd “On February 14th [1913] … we held a meeting in the Bromley Public Hall, Bow Road, and from it led a procession round the district. …To make sure of imprisonment, I broke a window in the police station … Daisy Lansbury was accused of catching a policeman by the belt, but the charge was dismissed. Zelie Emerson and I went to prison … .and began the hunger and thirst strike … On release we rushed back to the shop, found Mrs Lake scrubbing the table, and it crowded with members arranging to march to Holloway Prison to cheer us next day.”

24

Bow Palace, 156 Bow Rd was built at the rear of the Three Cups public house and had a capacity of two thousand.

“One Sunday afternoon I spoke in Bow Palace and marched openly with the people of Bow Rd. When I spoke from the window afterwards, a veritable forest of sticks was waved by the crowd. …

While I was in prison after my arrest in Shoreditch …. a Meeting …. was held in Bow Palace on Sunday afternoon, December 14th. After the Meeting it was arranged to go in procession around the district and to hoot outside the houses of hostile Borough Councillors.”

Sylvia Pankhurst – Women over the age of twenty-one were eventually enfranchised in 1928

[youtube 73844XHY6Y0 nolink]

Maps reproduced courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute

Postcard reproduced courtesy of Libby Hall Collection at Bishopsgate Institute

Photograph of Suffragette in Holloway courtesy of LSE Women’s Library

Copy of The Women’s Dreadnought courtesy of Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives

East London Suffragette Festival runs until 10th August

East London Suffragettes by Sarah Jackson & Rosemary Taylor is published by The History Press

You may also like to read about

Jemmy Catnach’s Cries Of London

Jemmy (James) Catnach of Monmouth Court was celebrated for publishing ballads, penny awfuls, and children’s farthing and halfpenny chapbooks. As publisher, compositor and poet, he established the Seven Dials Press in 1813 and ran it until he retired to be landlord of a tavern in Barnet in 1838. Such was Catnach’s love for ballads, he kept a fiddler on the premises at one time so that ballad singers could come in and audition their compositions for publication. Of all the Cries of London I have published these are most modestly produced and crudely wrought images, yet I love them for their strong images and graphic vitality.

Clothes Pegs, Props & Lines – Come buy and save your clothes from dirt, they’ll save you washing many a shirt!

Filberts – I sell them for a groat a pound and warrant them all good and sound!

Sweep – If you rightly understand me, with my brush, broom and my rake, such cleanly work I’ll make…

Sweep – If you rightly understand me, with my brush, broom and my rake, such cleanly work I’ll make…

Peas & Beans – Come buy my Windsor beans and peas, you’ll see no more this year like these!

Peas & Beans – Come buy my Windsor beans and peas, you’ll see no more this year like these!

Toys for Girls & Boys – only a penny, or a dirty phial or bottle

Toys for Girls & Boys – only a penny, or a dirty phial or bottle

Strawberries – Strawberries & cream are charming and sweet, mix them and try how delightful to eat

Strawberries – Strawberries & cream are charming and sweet, mix them and try how delightful to eat

When Good Friday comes, Hot Cross Buns!

When Good Friday comes, Hot Cross Buns!

Oranges – I sell them at two for a penny, ripe, juicy and sweet, just fit for to eat, so customers buy a good many

Oranges – I sell them at two for a penny, ripe, juicy and sweet, just fit for to eat, so customers buy a good many

Milk Below! – Rain, frost or snow, or hot or cold, I travel up and down, the cream & milk you buy from me is the best in town for custards, puddings, or for tea, there’s none like those you’ll buy from me

Milk Below! – Rain, frost or snow, or hot or cold, I travel up and down, the cream & milk you buy from me is the best in town for custards, puddings, or for tea, there’s none like those you’ll buy from me

Crumpling Codlings – Come buy my Crumpling Codlings, some of them you may eat raw, of the rest make dumplings

Crumpling Codlings – Come buy my Crumpling Codlings, some of them you may eat raw, of the rest make dumplings

Cherries – Here’s round and sound, black and white heart cherries, twopence a pound!

Cherries – Here’s round and sound, black and white heart cherries, twopence a pound!

Toy Lambs to sell – If I had as much money as I could tell, I never would cry young lambs to sell!

Toy Lambs to sell – If I had as much money as I could tell, I never would cry young lambs to sell!

You may also like to take a look at these other sets of the Cries of London I have collected

More John Player’s Cries of London

More Samuel Pepys’ Cries of London

Geoffrey Fletcher’s Pavement Pounders

William Craig Marshall’s Itinerant Traders

H.W.Petherick’s London Characters

John Thomson’s Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana II

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana III

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders