Clive Murphy & Joan Lauder, The Cat Lady

Joan Lauder, The Cat Lady of Spitalfields (1924-2011)

In recent years, the Cat Lady of Spitalfields has become a legendary figure in East End lore, acquiring an entire mythology of stories as time goes by. In my imagination, she is a mysterious feline spirit in human form that prowls the alleys and back streets – a self-appointed guardian of the stray cats and a lonely sentinel embodying the melancholy soul of the place.

Imagine my delight to discover that Clive Murphy, the Oral Historian who lives above the Aladin Curry House, befriended her and recorded her entire biography over many months in 1991. Now the Cat Lady has a name, Joan Lauder, and in Clive’s portrait above you see her sitting in his kitchen at 132 Brick Lane, dictating into a tape recorder and looking uncannily feline in her dappled grey fur coat.

Although she was widely assumed to have died when she vanished from Spitalfields towards the end of the last century, in fact Joan Lauder lived in a series of homes from 1995 until her death just four years ago. Clive remained in contact with Joan and was one of her only two regular visitors right up to the end. Over the twenty years they knew each other, an unlikely and volatile friendship grew between Clive & Joan based upon mutual curiosity.

Clive Murphy has decided that now at last the truth about the Cat Lady can be revealed and he is editing his transcripts into a book of Joan’s life entitled ‘Angel of the Shadows.’ Thus Clive has permitted me to publish his introduction today as a sneak peek, accompanied by some of the photographs that he took when he accompanied Joan the Cat Lady on her rounds back in the early nineties, tending to the feral creatures of Spitalfields that no-one else loved.

At Angel Alley, Whitechapel, 5th March 1992

Feeding the cat from The White Hart in Angel Alley, 5th March 1992

In Gunthorpe St, 5th March 1992

Buying cat food at Taj Stores, Brick Lane, 3rd August 1992

In Wentworth St, 3rd August 1992

Calling a cat, Bacon St, 3rd August 1992

The cat arrives, Bacon St, 3rd August 1992

Alley off Hanbury St, 2nd August 1992

Hanbury St, 26th November 1995

At Aldgate East, 3rd August 1992

At Lloyds, Leadenhall St, 3rd August 1992

Walking from Angel Alley into Whitechapel High St, 3rd August 1992

Beware Of The Pussy, 132 Brick Lane, 26th November 1995

Clive visits Joan in her Nursing Home, 1995

ANGEL OF THE SHADOWS, The Life of the Cat Woman of Spitalfields

The women I have loved you could count upon the digits of one hand – my mother, her mother, our loyal companion Maureen McDonnell, the poet Patricia Doubell and the demented, incontinent Joan Lauder, the Cat Lady of Spitalfields who, in 1991, when I first spoke to her was already my heroine, a day-and-night-in-all-weathers Trojan, doggedly devoting herself to cats because human beings had for too long failed her. She looked at me with suspicion when I suggested we tape record a book. Only my bribe that half of any proceeds of publication would fall to her or her favoured charities and enable the purchase of extra tins of cat food persuaded her at least to humour me. I could swear I saw those azure eyes, set in that pretty face, dilate. I had entrapped her with the best of intentions as she, I was to learn, often entrapped, also with the best of intentions, the denizens of the feral world to have them spayed or neutered in the interests of control. But to the end, her end, I don’t think she ever trusted or respected me. I once found her surreptitiously laying down Whiskas in my hallway for my own newly-adopted cat which I named Joan in her honour. And she once spat the expletive ‘t***’ at me in a tone of total dismissal. To be called a foolish and obnoxious person was hardly comforting, given that I believe my own adage ‘in dementia veritas’ holds all too often true.

– Clive Murphy

Clive’s cat ‘Joan’ in his kitchen, 6th July 1996

Mustakim and Joan, 11th April 1998

Joan on the rooftops of Brick Lane, 21st February 1996

Mullah’s pupil with Joan, 10th April 2001

15th June 1995

Photographs copyright © Clive Murphy

You may like to read my other stories about Joan Lauder

Remembering the Cat Lady of Spitalfields

and take a look at my other stories about Clive Murphy

The Metropolitan Machinists’ Co, 1905

A few weeks ago – courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute – I published the 1896 cycling accessories catalogue of the Metropolitan Machinists’ Co of Bishopsgate Without and today I publish their catalogue from 1906 as an illustration of how rapidly cycling advanced into the new century, especially – as you will see – in the applied science of the ‘Anatomical Saddle’ which offered extra support to the ischial tuberosities.

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

The Metropolitan Machinists’ Co, 1896

Tea With Victor & Marilyn

Victor Lownes & Marilyn Cole

To cheer me up after I broke my arm, the glamorous Barbara Haigh – ex-Bunny & ex-landlady of The Grapes in Limehouse – drove me up to the West End in her nippy two-seater sports car to have tea with Victor Lownes – who ran the British Playboy Club between 1965 & 1981 – and his wife Marilyn Cole – the first full-frontal centrefold Playmate – in their palatial white stucco mansion at Hyde Park Corner.

Sprightly and lithe at eighty-seven, Victor is a sovereign example to any moralist who might assume that the life of a committed playboy inevitably leads to dissipation and despair. After bedding thousands of women in his long career as a lothario, Victor met his match in Marilyn, the Playmate with more than the rest.

Barbara & I discovered Victor & Marilyn happily inhabiting the small basement rooms of their vast townhouse, cosy down there like two bunnies in a burrow. The unlikely conversation that ensued was shot through with ironies and contradictions – and, thanks to a fly on the wall, you can read it for yourself. Contributing Photographer Patricia Niven joined the party too and even followed Marilyn & me into the bedroom to admire Marilyn’s centrefold.

Victor: I’ve got rather tired of living upstairs.

Marilyn: Well it’s big upstairs.

Victor: Too many stairs and things.

The Gentle Author: I wanted to ask you, “Are you a playboy?”

Victor: Not really, I’m a happily married man.

The Gentle Author: But were you once?

Victor: Oh yes, I was. Ask them. “Was I a playboy?”

Barbara: Yes, dear. The opening gambit was, “Wanna fool around?”

The Gentle Author: I’m told that you invented ‘the bunny girl.’

Victor: The Playboy bunny was the trademark of the company from the start.

The Gentle Author: So that already existed?

Victor: Oh yes. In Playboy magazine, there was a tall figure dressed as a bunny.

Barbara: But it was a male bunny, wasn’t it?

Victor: Yeah, it was a male bunny.

Barbara: Smoking jacket…

Victor: Tuxedo and whatever … the idea grew out of that.

The Gentle Author: Was it your idea?

Victor: I don’t remember whose idea it was. It may have been mine or Hugh Hefner’s. We opened the first Playboy Club there and there was a line waiting to get in every night.

The Gentle Author: What I want to know is what drew you into that world?

Victor: A photographer friend of mine brought Hefner to a party at my bachelor apartment. And Hefner started telling me about his magazine, that he was just starting. At that time there was no Playboy Club, I was interested in clubs and what have you, so he asked me if I’d like to join in the venture. So I did.

The Gentle Author: What is it about the clubs that appealed to you?

Victor: First of all, in those days I drank a bit. I was about twenty-one years old and I had just come of age where I could legally buy a drink at a bar. I was curious about that. And I also saw it as a big money-making opportunity. Twenty five dollars got you a lifetime membership of the playboy club. We advertised in Playboy Magazine. Enormous success.

Marilyn: It was a lot to do with the music too, wasn’t Victor? You liked jazz very much.

Victor: We had jazz groups in there. And several floors with different cabarets and it was very successful. After Chicago, we went to New York, San Francisco followed, and Los Angeles and Dallas, Texas. We had clubs all over the country, about forty of them altogether.

The Gentle Author: And this was a source of joy to you…

Victor:V. The joy of making money. That’s a nice joy.

The Gentle Author: And?

Victor: And the joy of being able to date any of these girls.

[Barbara & Marilyn laughing]

Victor: We had a strict rule that the bunnies were not allowed to date the customers but…

Barbara: That was the first rule they said to us when we started at Playboy, “You’re not allowed to go out with customers. You’re not allowed to date any of the staff members. However Mr. Lownes is single.” [Laughing]

Victor: Actually when we came to opening the London club, we didn’t enforce this rule.

Barbara: Well, you lifted it. I think your exact words were “I will not stand in the way of true romance.”

Victor: Was that right?

Barbara: If we met someone through our work that we fell in love with, but what they didn’t want was us going out with a different customer every night.

Victor: We were especially not interested in being accused of running a prostitution ring or anything.

The Gentle Author: How did you meet Barbara?

Victor: She was a bunny.

The Gentle Author: What was your first impression of Barbara?

Victor: I thought she was a bit overweight.

Barbara: I am now! But I was skinny as a rake in those days. You’re horrible to me. He introduced me to Tony Curtis and he said, “This is Barbara, the oldest and fattest bunny.”

The Gentle Author: (Asks Victor) Do you remember that?

Victor: The oldest…?

Barbara: (adopts Victor’s accent) “This is Barbara, one of our oldest and fattest bunnies.”

Marilyn: Oh, I can’t believe he would’ve said that.

Barbara: He did! I swear to God.

Victor: I introduced her to Tony Curtis!

Marilyn: I can’t believe he did that.

Barbara:. He did! He thought it was very funny.

Victor: I’m guilty!

Marilyn: Apologise now.

Victor: I apologise.

The Gentle Author: What did Tony Curtis say?

Barbara: He just scowled at Victor, then he kissed my hand and said “I’m very pleased to meet you, Barbara.”

The Gentle Author: Well, that was decent of him.

Barbara: I mean he was gorgeous. He looked as if he’d just walked straight out of a movie set. He was so impossibly handsome in the flesh.

The Gentle Author: (Asks Victor) So how was it that Marilyn stole your heart then?

Barbara: This is why he doesn’t remember me because Marilyn & I started on the same day.

Marilyn: (To The Gentle Author) Come here and I’ll show you something. Inner sanctum!

[Marilyn leads The Gentle Author to the bedroom]

The Gentle Author: We’re going next door! I was asking how did Marilyn steal your heart?

Marilyn: There – that’s how. That’s my centerfold! Let me turn the light on.

[Lights go on to reveal framed copy of Marilyn’s Playboy centrefold picture on the bedroom wall]

The Gentle Author: Wow!

Marilyn: Victor was my mentor. In Playboy terms, he discovered me. He sent me to Chicago and I became the first Playboy full frontal.

The Gentle Author: Who’s idea was that?!

[Marilyn leads The Gentle Author back to Victor]

Victor: It was called the Pubic Wars. And Hefner had to decide whether to do it or not. He didn’t really want to. It was Guccione who started it – Guccione was coming up, up, up with Penthouse. So Hefner had to take a serious decision and they decided to do that.

The Gentle Author: (To Marilyn) Did they ask you or did you volunteer?

Marilyn: That’s another story.

The Gentle Author: (To Victor) I don’t believe it was only because of the centerfold that Marilyn stole your heart.

Victor: No, I don’t think it was either.

The Gentle Author: So what it is about Marilyn? After all these women, why Marilyn?

Victor: Well she was amazing, she was a standout in personality and looks.

Barbara: I was there when you first clapped eyes on her on the day we started. Obviously word had got round, someone said, “Get Victor up here quick” [laughs] His jaw dropped and he was just taken with her immediately.

Victor: I was.

Barbara: I think your exact words to me were, “She’s unusually beautiful.”

Victor: I said that?

Barbara: Yep.

Victor: Well there you are, you see. And she still is, in my mind.

The Gentle Author: Do you think the Playboy experience changed your view of humanity?

Victor: Perhaps it changed my view of what humanity can be – because the Playboy thing was very sympatico, wasn’t it?

Barbara: I think so.

Victor: I mean everybody got along with everybody. And they all made money at it – our Bunnies made at least thirty pounds a week when they started in 1966.

Barbara: Thirty-five actually.

Victor: I mean it doesn’t sound like anything today…

Barbara: I think I was earning more than my father. I was working as many hours as I could because I was saving up to get a deposit to buy a flat, and I think I did it within about six weeks. I was working sixty, seventy, eighty hours a week.

Victor: What are we talking about?

Barbara: You’re talking about Playboy’s ethos, I think you call it.

Victor: We had bunnies of every colour. We had Indian bunnies too, African and Indian bunnies.

Barbara: It was frowned upon in the States, wasn’t it?

Marilyn: Playboy was very important in Race Relations, they were the first to hire black comedians in white clubs.

Victor: That’s right. Hefner of course, Equal Rights, you know his history with… Equal Rights?

The Gentle Author: … Civil Rights.

Marilyn: Civil Rights, that was part of his philosophy, and Victor’s, and everyone who worked there. I mean – and black bunnies. So there was never any racial discrimination – the opposite actually.

Victor: It was a good policy and it worked well. It didn’t drive any customers away. And we opened up clubs in the South, New Orleans and in Memphis, Tennessee. It was unique in those places but we got them to accept it and we adopted the same policy everywhere.

The Gentle Author: So it was about equality of race within the clubs and about equality of gender too, that women worked on an equal level as men?

Victor: Equal? They were making more than the men! [Laughs]

The Gentle Author: Tell me about opening up in London. What were the challenges here?

Victor: I don’t remember that there were any challenges. We had co-operation of everybody the minute we set foot in the country. I remember I came with a huge box of Playboy cigarette lighters that were all primed and ready to go. And as I came through customs, I kept handing them out to the people who were inspecting me – I said, “I’ve got all these things and you’re entitled to one of them.” In those days everybody smoked, now nobody smokes. You don’t see any ashtrays around here, I don’t think anybody we know smokes.

The Gentle Author: Do you think you’ve been lucky?

Victor: With everyone in the world, chance plays a big part in what happens to you and there isn’t anything that can change that. I think most people just fall into situations.

The Gentle Author: There’s circumstances and there’s character. There’s being in the situation and there’s rising to it. It sounds like you took to it like a duck to water – or like a rabbit out of a hole.

Marilyn: But he’s got the brain for it. He’s scarily clever.

Victor: I’m pretty clever.

Barbara: Smartarse!

Victor: There’s a photo up there on the wall – it says “Merry Christmas Pooky” or something.

Marilyn: [indicates the picture] That’s Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr.

Victor: That’s when the Beatles were just starting out and they were at my house.

Barbara: (To The Gentle Author) Pooky’s his daughter.

Victor: I put them on the phone to her….

Marilyn: When Barbara and I joined the Playboy Club in 1971 it was already different to when it opened in 1966. We loved the stories of the opening night, when they had Margot Fonteyn, Rudolf Nureyev, Jean-Paul Belmondo and Ursula Andress at the club on Park Lane. And Mia Farrow, of course. Then Francis Bacon was a friend of Victor. He used to come and gamble at Playboy.

Victor: Yeah, I had a couple of his paintings but unfortunately I sold them when the price got too attractive. They were offering me a quarter of a million pounds each for them, so I sold them. They’d be worth ten million now.

Barbara: Isn’t it sick?

Victor: One was a big portrait of Lucien Freud.

Barbara: (to Marilyn) We came from such different walks of life and then all a sudden we were thrown into this world of glamour….

Marilyn: We weren’t thrown into it, we went to it.

Barbara: You thought, hang on a minute, I feel like a duck out of water – but then after a while you got used to it.

Marilyn: The fact that Victor was like he was – we knew we were in good hands. We could have gone to the Penthouse Club – and we would not have been in good hands with Guccione. He lost his licence very quickly.

The Gentle Author: What was the difference?

Marilyn: Playboy abided by the law in everything they did. Actually there’s a real conservatism about Victor and Hefner. Whereas Guccione – I’m not putting him down – he did something good for himself.

Victor: Who you talking about?

Marilyn: Bob Guccione. Penthouse. He was a different type of person. He had a gold medallion. I’d never have gone out with anyone with a gold medallion.

Victor: Medallion!

The Gentle Author: I’ve got a medallion.

Victor Lownes

Victor in the sixties when he opened the London Playboy Club

Victor’s portrait on horseback

One of Victor’s many headlines

Victor’s portrait from the seventies

Marilyn and her centrefold

Victor & Marilyn in the seventies

Victor Lownes & Marilyn Cole

Photographs copyright ©Patricia Niven

You may also like to read about

At the Playboy Bunnies’ Reunion

Yet More From Philip Mernick’s Collection

In sharp contrast to Horace Warner’s Spitalfields Nippers, this latest selection from Philip Mernick‘s collection of cartes de visite by nineteenth century East End photographers, gathered over the past twenty years, shows the offspring of the bourgeois professional classes. No doubt the doting parents delighted in these portraits of their little darlings trussed up like turkeys in their fancy outfits, but there is not a single smile among them.

1870

1870

1870

1870s

1870s

1880

1885

1880s

1880s

1880s

1898

1890

1900

1900

1900

1910

1910

1910

Photographs reproduced courtesy of Philip Mernick

You may also like to take a look at

Portraits from Philip Mernick’s Collection

So Long, Alfons Jedrzejewski Of Puma Court

I publish this as a tribute to Alfons Jedrzejewski – widely known as Alec – who lived in the Norton Folgate Almshouses for forty-five years and died there last week aged eighty-nine. I used to meet him regularly, coming and going through the gates, and now I shall always think of him when I walk through Puma Court.

Alfons Jedrzejewski (1926-2015)

I met Alfons Jedrzejewski – widely known as Alec – just over two years ago, when he returned to the Norton Folgate Almshouses in Puma Court, off Commercial St, after a ten month sojourn in Shepherds Bush, while the hundred and fifty year old dwellings underwent a renovation. He invited me round for tea in his newly-painted flat where I found him toying with the novelty of the new controls for his heating and hot water. Primarily, Alec was relieved to be back in the place he had lived for the more than forty years. “I prefer to be here,” he confided to me in understatement, rolling his eyes to communicate the alien nature of life in West London, “I feel more happy here.”

Hale and healthy then at eighty-six, Alec was born in 1926 in Tors in Poland. He served in the Polish army during World War II and came to London in May 1946 to start a new life after he discovered that all his relatives in Poland had been killed by Stalin. Just a few snaps and photobooth portraits in a frame upon the wall of Alec’s living room attested to the existence of his family, yet his flat also contained the memory of the last twenty-three years of his marriage to his wife, Halina, who had died nineteen years earlier.

When he first came to London, Alec worked as a house painter until – following Halina’s prudent advice – he took a job on the railway that would give him a pension, working for twenty-one years in the parcels office at Liverpool St Station. “A friend of mine, who worked at Kings Cross and lived at 8 Wilkes St, told me about these flats,” explained Alec, emphasising the importance he placed upon mobility, “you have good transport links here, underground, buses and British Rail.”

This was a significant detail because the unfailing highlight of Alec’s week was a trip to Leytonstone to visit his long-term girlfriend, Maria, and take her the fresh fish that she loved so much, which he bought for her at Asda. Like so many refugees before him, Alec discovered in Spitalfields a safe haven from the brutality of the wider world and lived out his existence peacefully here until the end. After my interview, I met Alec and Maria once or twice, strolling together arm-in-arm in the Bethnal Green Rd like a couple of teenage sweethearts.

For many years I passed the railings of the almshouses daily as I walked through Puma Court, leaving the clamor of Commercial St behind me and entering the peaceful streets of eighteenth century houses beyond. So I was eager to step through the old iron gates at last, when I visited Alec in this appealing backwater in the midst of the city.

Established at first in Blossom St in 1728, the current site for the Norton Folgate Almshouses was purchased in 1851 when the widening of Commercial St – to permit the increasing traffic from the London Docks – required the demolition of the former premises.

This neatly proportioned pair of brick houses in Puma Court, each containing eight rooms on two storeys, were built by architect T. E. Knightley in 1860. The first residents received two shillings and sixpence a month, a ticket for a quartern loaf of bread per week, six hundredweight of coal on 21st December and materials for dinner on Christmas Day. There were fifteen single people and one married couple living there in 1897, they each had one room and the average age was sixty-four. It was a humane endeavour, offering a secure refuge for those who could no longer earn a living and existing in sharp contrast to the poverty which prevailed ein Spitalfields at that time.

Over one hundred and fifty years, the Norton Folgate Almshouses in Puma Court have offered a safe harbour for life – as Alec’s story attests – and these thoughtfully-conceived dwellings continue to serve their purpose into another century, as the need for good quality housing at an affordable price in Spitalfields becomes ever more pressing.

Sophie Charalambous, Artist

Trinity Green Almshouses, Mile End

You only have until this Sunday 8th March to catch Sophie Charalambous‘ exhibition at Jessica Carlisle Gallery. I was captivated by the soulful melancholy beauty of Sophie’s paintings of London from the moment I saw them, so Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I went over to visit her yesterday at her studio in London Fields where she has been working in an old garment factory for the past fifteen years. While her faithful hound who sneaks his way into many of the paintings dozed on the sofa, Sophie showed us her sketchbooks and I recognised a kindred spirit in Sophie’s love of the Thames – a romance nurtured by regular visits to the foreshore at Wapping and finding expression in magnificent moody paintings.

House by the Thames at Bankside

Drovers in London Fields

Sophie Charalambous

Life, Still, Winter

Pageant

Wapping Pierhead

On the Beach at Wapping Pierhead

Sketch for Wapping Pierhead, with raindrops

Warehouses in Wapping

Sketch for Trinity Green Almshouses, Whitechapel

Sophie Charalambous in her studio in London Fields

Paintings copyright © Sophie Charalambous

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Sophie Charalambous’ exhibition is at Jessica Carlisle Gallery, 83 Kinnerton St, SW1X 8ED, until Sunday 8th March at 6pm

You may also like to read about

Madge Darby, Historian of Wapping

Adam Dant’s Stories Of Hackney Old & New

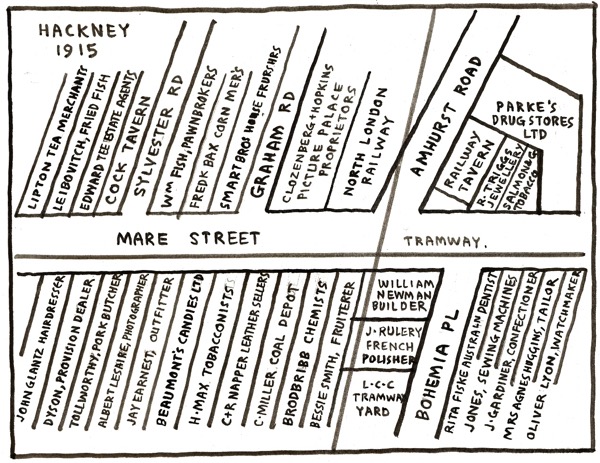

Contributing Artist Adam Dant presents this map of Hackney that he has created as a complement to his maps of Shoreditch & Clerkenwell

1. In the sixteenth century, Hackney is the first village near London accommodated with coaches for occasional passengers, hence the name of Hackney carriages.

2. 1521 – Thomas More’s third daughter Cecilia marries Giles Herond in ‘Shackelwell’ & resides at an ancient manor there.

3. 1536 – Henry VIII is reconciled with his daughter Mary at Brook House, Hackney. Mary had not spoken to her father in five years.

4. 1559 – London’s last case of leprosy is recorded at St Bart’s isolation house, ‘The Lock Hospital.’ Established in 1280, it was Hackney’s first hospital.

5. 1598 – Playwright Ben Jonson kills fellow actor Gabriel Spencer in a duel in the fields at Shoreditch and receives a felon’s brand on this thumb.

6. 1647 – The presence of Elizabeth of Bohemia & The Elector Palatine at an entertainment at ‘The Black & White house’ is commemorated in a window bearing their arms.

7. 1654 – Diarist John Evelyn visits Lady Brook’s celebrated garden at Brook’s House, Hackney.

8. 1682 – Prince Rupert discovers a new and excellent method of boring guns at his watermill in Homerton, but the secret of Prince Rupert’s metal dies with him.

9. 1701 – A bull baited by twelve dogs breaks loose at Temple Mills. Confusion and uproar ensue amongst the crowd of three thousand and a nine year old girl barely survives being tossed by the enraged animal.

10. 1750 – Legislature obliges people not to keep any other dogs but ‘such that are really useful’ after Charles Issacs at Hackney is bit by a dog and dies raving mad.

11. In the seventeenth century, the noted ‘Hackeny Buns’ of Goldsmith’s Row are as well regarded as those of ‘The Bun House’ at Chelsea.

12. 1665 – To be seen at Cooper’s Gardens for sixpence a person, the greatest curiosity that was ever seen, a white Dutch radish two feet and two inches round.

13. 1667 – In the church of St Augustine, Samuel Pepys eyes Abigail Vyner ‘a lady rich in Jewels but mostly in beauty, almost the finest woman that I ever saw.’

14. 1788 – In Cat & Mutton fields is seen the inhuman sport where any contestant catching ‘a soapy pig by the tail & holding it over his head’ wins a gold laced hat.

15. 1797 – The Hackney Militia gain a reputation for bumbling incompetence during the Napoleonic Wars.

16. 1811 – At The Mermaid Tavern pleasure gardens James Sadler & Captain Paget Royal Navy ascend in a balloon decorated in honour of The Prince Regent on his birthday.

17. 1787 – Plants from ‘Loddige’s Gardens’, originally owned by John Busch, gardener to Catherine the Great, are transferred to Crystal Palace.

18. 1805 – A stagecoach is broken to pieces and two ladies suffer severely when the vehicle overturns on the edge of a precipice at Hackney Wick.

19. 1816 – Brooke House, former home of Lady Brookes and Balmes House at Hoxton are opened as private lunatic asylums.

20. 1821 – Repairs are made at Hackney’s oldest brewery, Mrs Addison’s Woolpack Brewery on the Hackney Brook.

21. 1848 – Prince Albert opens The Hospital for Diseases of the Chest and in 1867 Princess Louise opens the North-Eastern Hospital for Sick Children in the Hackney Rd

22. 1850 – The construction of Victoria Park sweeps way hovels, formerly known as‘Botany Bay,’ and the inhabitants who are sent to another place bearing the same name.

23. 1866 – At the Parkesine Works in Wallis Rd and Berkshire Rd, Alexander Parkes manufactures the world’s first plastic.

24. 1880. – Hackney Wick firm Carless Capel & Leonard claim to have invented the term ‘petrol’ (St Peter’s Oil).

25. 1902 – Smallpox re-surfaces in Hackney with contagion found in a family of costermongers living in filthy conditions in Sanford Lane.

26. 1959 – Richard Burton films a scene for John Osborne’s ‘Look Back in Anger’ at Dalston Junction Railway Station.

27. 1952 – The great fog causes death and chaos in Hackney when a motor-cyclist collides with a bus, a man dies on a railway line and crime has a little hey-day.

28. 1964 – Teenagers at The Dalston Dance Hall adopt the ‘purple heart’ pill popping craze.

29. 1970 – M.O.D investigates the sighting of a U.F.O over Hackney by Mr Douglas Lockhart, gliding across a clear sky at 11.35pm on a Saturday night.

30. 2007 – Terry Castle and volunteers at Bethune Rd unearth a hoard of Nazi twenty dollar gold coins whilst digging a frog pond.

31. 2011 – Grandmother Pauline Pearce ‘Hero of Hackney’ bravely stands up to a gang of looting rioters at the Pembury Estate.

32. Thousands of ‘booze fuelled revellers’ leave a trail of destruction along the Regents Canal ‘Canalival’ floating party.

The map of Hackney Old & New was commissioned from Adam Dant by James Goff who has been a patron of artists in Hackney since the eighties and you may see the original displayed in the Hackney office of Stirling Ackroyd in Mare St.

You may also like to take a look at

Adam Dant’s Stories of Shoreditch Old & New

Adam Dant’s Stories of Clerkenwell Old & New