At Arthur Beale

Did you ever wonder why there is a ship’s chandler at the top of Neal St where it meets Shaftesbury Avenue in Covent Garden. It is a question that Alasdair Flint proprietor of Arthur Beale gets asked all the time. ‘We were here first, before the West End,’ he explains with discreet pride,‘and the West End wrapped itself around us.’

At a closer look, you will discover the phrase ‘Established over 400 years’ on the exterior in navy blue signwriting upon an elegant aquamarine ground, as confirmed by a listing in Grace’s Guide c. 1500. Naturally, there have been a few changes of proprietor over the years, from John Buckingham who left the engraved copper plate for his trade card behind in 1791, to his successors Beale & Clove (late Buckingham) taken over by Arthur Beale in 1903, and in turn purchased by Alasdair Flint of Flints Theatrical Chandlers in 2014.

‘Everyone advised me against it,’ Alasdair confessed with the helpless look of one infatuated, ‘The accountant said, ‘Don’t do it’ – but I just couldn’t bear to see it go…’

Then he pulled out an old accounts book and laid it on the table in his second floor office above the shop and showed me the signature of Ernest Shackleton upon an order for Alpine Club Rope, as used by Polar explorers and those heroic early mountaineers attempting the ascent of Everest. In that instant, I too was persuaded. Learning that Arthur Beale once installed the flag pole on Buckingham Palace and started the London Boat Show was just the icing on the cake. Prudently, Alasdair’s first act upon acquiring the business was to acquire a stock of good quality three-and-a-half metre ash barge poles to fend off any property developers who might have their eye on his premises.

For centuries – as the street name changed from St Giles to Broad St to Shaftesbury Avenue – the business was flax dressing, supplying sacks and mattresses, and twine and ropes for every use – including to the theatres that line Shaftesbury Avenue today. It was only in the sixties that the fashion for yachting offered Arthur Beale the opportunity to specialise in nautical hardware.

The patina of ages still prevails here, from the ancient hidden yard at the rear to the stone-flagged basement below, from the staircase encased in nineteenth century lino above, to the boxes of War Emergency brass screws secreted in the attic. Alasdair Flint cherishes it all and so do his customers. ‘We haven’t got to the bottom of the history yet,’ he admitted to me with visible delight.

Arthur Beale’s predecessor John Buckingham’s trade card from 1791

Nineteenth century headed paper (click to enlarge)

Alasdair Flint’s office

Account book with Shackleton’s signature on his order for four sixty-foot lengths of Alpine Club Rope

Drawers full of printing blocks from Arthur Beale and John Buckingham’s use over past centuries

Arthur Beale barometer and display case of Buckingham rope samples

Nineteenth century lino on the stairs

War emergency brass screws still in stock

More Breton shirts and Wellingtons than you ever saw

Rope store in the basement

Work bench with machines for twisting wire rope

Behind the counter

Jason Nolan, Shop Manager

James Dennis, Sales Assistant

Jason & James run the shop

Receipts on the spike

Arthur Beale, 194 Shaftesbury Avenue, WC2 8JP

You may also like to read about

Viscountess Boudica’s Valentines

Viscountess Boudica of Bethnal Green confessed to me that she has never received a Valentine in her entire life and yet, in spite of this unfortunate example of the random injustice of existence, her faith in the future remains undiminished.

Taking a break from her busy filming schedule, the Viscountess granted me a brief audience to reveal her intimate thoughts upon the most romantic day of the year and permit me to take these rare photographs that reveal a candid glimpse into the private life of one of the East End’s most fascinating characters.

For the first time since 1986, Viscountess Boudica dug out her Valentine paraphernalia of paper hearts, banners, fairylights, candles and other pink stuff to put on this show as an encouragement to the readers of Spitalfields Life. “If there’s someone that you like,” she says, “I want you to send them a card to show them that you care.”

Yet behind the brave public face, lies a personal tale of sadness for the Viscountess. “I think Valentine’s Day is a good idea, but it’s a kind of death when you walk around the town and see the guys with their bunches of flowers, choosing their chocolates and cards, and you think, ‘It should have been me!'” she admitted with a frown, “I used to get this funny feeling inside, that feeling when you want to get hold of someone and give them a cuddle.”

Like those love-lorn troubadours of yore, Viscountess Boudica has mined her unrequited loves as a source of inspiration for her creativity, writing stories, drawing pictures and – most importantly – designing her remarkable outfits that record the progress of her amours. “There is a tinge of sadness after all these years,” she revealed to me, surveying her Valentine’s Day decorations,” but I am inspired to believe there is hope of domestic happiness.”

You may also like to take a look at

Viscountess Boudica’s Domestic Appliances

Viscountess Boudica’s Halloween

Viscountess Boudica’s Christmas

Read my original profile of Mark Petty, Trendsetter

and take a look at Mark Petty’s Multicoloured Coats

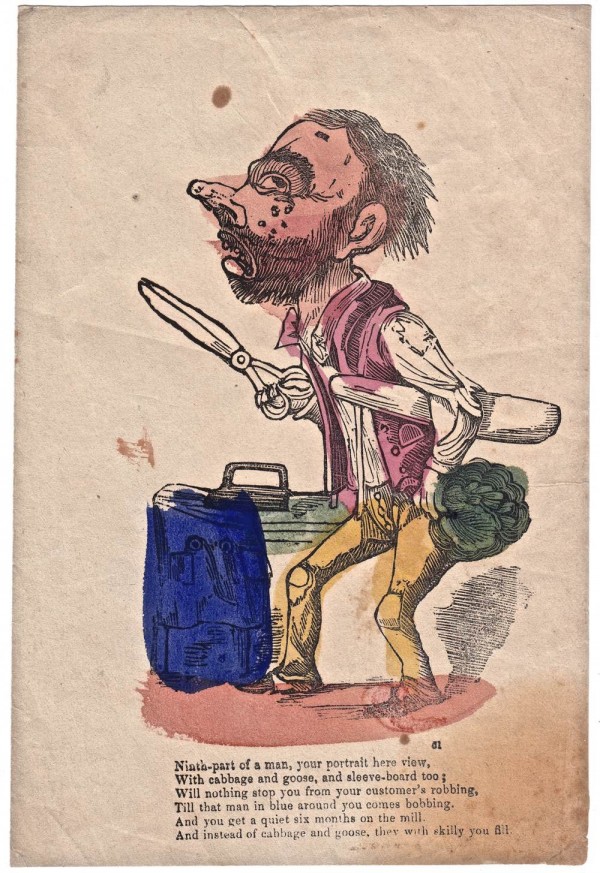

Vinegar Valentines

As Valentine’s Day approaches and readers are preparing their billets-doux, perhaps some might like to contemplate reviving the Victorian culture of Vinegar Valentines?

When I met inveterate collector Mike Henbrey last summer in the final months of his life, he showed me his cherished collection of these harshly-comic nineteenth century Valentines which he had been collecting for more than twenty years.

Mischievously exploiting the expectation of recipients on St Valentine’s Day, these grotesque insults couched in humorous style were sent to enemies and unwanted suitors, and to bad tradesmen by workmates and dissatisfied customers. Unsurprisingly, very few have survived which makes them incredibly rare and renders Mike’s collection all the more astonishing.

“I like them because they are nasty,” Mike admitted to me with a wicked grin, relishing the vigorous often surreal imagination manifest in this strange sub-culture of the Victorian age. Mike Henbrey’s collection of Vinegar Valentines has now been acquired by Bishopsgate Institute, where they are preserved in the archive as a tribute to one man’s unlikely obsession.

Images courtesy Mike Henbrey Collection at Bishopsgate Institute

You might also like to look at

A Letter To The Times

Today, a new chapter opens in the story of our campaign to Save Norton Folgate with the publication of this letter in the The Times. Already a Judicial Review is scheduled in April to scrutinise the mishandling of British Land’s application by Boris Johnson and the Greater London Authority, now this letter asks Greg Clark, Secretary of State, to stage a Public Inquiry that can determine the best outcome for Norton Folgate.

To the Editor of The Times

We urge the Secretary of State, Greg Clark, to call in for his own determination – and hold a planning inquiry into – the British Land planning applications that are threatening the future of Norton Folgate in historic Spitalfields. This precious Conservation Area on the fringes of the City of London is under threat from plans by developer British Land to demolish a swathe of buildings for a banal office-led scheme. The plans were rejected by the democratically elected local Council, but this decision has been shamefully overruled by the Mayor of London, one of a string of permissions he has handed to developers against the will of local people and the mandate of local democracy.

Only a thorough public inquiry can determine the best outcome for this sensitive historic area. The Spitalfields Trust has commissioned its own scheme for the site from Burrell, Foley, Fischer Architects. This repairs and reuses the historic fabric, provides sensitive in-fill in keeping with the scale and character of the area as well as serving the interests of local businesses, particularly SMEs and micro enterprises, and the need for housing in the Borough. It has been independently costed, is viable, and could be delivered immediately and speedily, for a fraction of the development cost.

Signed

David Bailey CBE, Photographer

Alan Bennett, Writer

Clem Cecil, Director of SAVE Britain’s Heritage

Julie Christie, Actress

Dan Cruickshank, Architectural Historian

Ralph Fiennes, Actor

Mark Girouard, Architectural Historian

Tim Knox, Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum

Todd Longstaffe-Gowan, Garden Designer

Miriam Margolyes OBE, Actress

Suggs McPherson, Madness

John Nicolson MP, SNP spokesman on Culture, Media & Sport

Dame Sian Phillips, Actress

Jonathan Pryce, Actor

Charles Saumarez Smith, Chief Executive of the Royal Academy

Rohan Silva, Second Home

Rupert Thomas, Editor of World of Interiors

Jeanette Winterson, Writer

Please add your name to the illustrious list of those calling for a Public Inquiry by writing direct to the Secretary of State. The Spitalfields Trust suggest you include the following points in your letter which you can email to greg.clark.mp@parliament.uk or post to House of Commons, London, SW1A 0AA

- This is not just a very important case for London, it is also of national importance and has serious implications for Conservation Areas across the country.

- This fragile Conservation Area is protected by local Conservation Guidelines, which this application disregards.

- The vitality of the City does not depend upon demolishing some warehouses in Spitalfields.

- The democratic decision at a local level has been over-ruled by the centralised intervention of the Mayor of London.

- The Spitalfields Trust’s Conservation Scheme for Norton Folgate is independently costed and is viable. It could be delivered more quickly and far more cheaply than that proposed by British Land. It is based upon the repair of the existing historic buildings, with sensitive infill of empty sites in keeping with the Conservation Area.

- The Spitalfields Trust’s scheme would provide more affordable business accommodation, particularly for small businesses and provide more housing, both low cost and private, for the local borough.

- This case has given rise to substantial local and national controversy, and has been widely covered in the media.

- The whole-scale demolition of heritage assets in the Conservation Area conflicts fundamentally with national policies as set out in the National Planning Policy Framework in section 12 in relation to conserving and enhancing the historic environment.

Follow the Campaign at facebook/savenortonfolgate

Follow Spitalfields Trust on twitter @SpitalfieldsT

You may also like to take a look at

Beware the Curse of Norton Folgate!

Standing up to the Mayor of London

An Offer to Buy Norton Folgate

An New Scheme For Norton Folgate

Joining Hands to Save Norton Folgate

Dan Cruickshank in Norton Folgate

Taking Liberties in Norton Folgate

Pamela Cilia, Truman’s Bottling Girl

Pamela Cilia

The reputation of the Truman’s bottling girls has passed into legend in Spitalfields. In the course of my interviews, so many people have regaled me with tales of this heroic tribe of independent spirited females who wore dungarees and clogs which thundered upon the cobbles as made their way through the narrow streets en masse, that I have been seeking an interview with one of these glamorous and elusive creatures for years.

Consequently, I was more than happy to make a trip to Rainham to pay a call upon Pamela Cilia, who proved to be a fine specimen of a bottling girl, full of vitality, sharp intelligence and strong opinions to this day. Illuminated by sparkling charisma and filling with joyous emotion as she recounted her story, Pamela was no disappointment.

“I loved it, I loved it, really loved it. But when my husband discovered I was going to work at Truman’s, he said, ‘I don’t want you working in that *******.’ He called it a certain place. Yet he already worked there, so I said to him, ‘If you give the place such a bad name, why are you working there?’ My first job was at Charrington’s in Mile End Rd until that closed down, then I worked for Watney Mann’s for seven years in Sidney St before they sold it to Truman’s, and that’s how we all ended up in Truman’s.

In the bottling plant, you had the filler, then you had the discharger and the labelling. The boxes came down and we filled them up. If a vacancy appeared on a machine, they did it by seniority – I think there were about seven machines. They had one ‘Galloping Major’ that done pints and quarts, and all the others were little bottles. They also had the canning machine. I was mainly on the canning machine.

We never had all this ‘safety,’ like now. We never wore glasses, we never had earpieces, so it was really dangerous, especially when the bottles went ‘bang’– especially when you had one in your hand and it exploded. You’d be getting them out of the pasteuriser, then all of a sudden ‘bang, bang bang, bang!’ because they hit against one another and they were hot from the pasteuriser.

I was forty-four and my children were all at school. In those days we lived in two rooms. Two pound a week, that’s what we paid. And my friend Doris used to take the kids to school and she used to bring them home. I clocked in at half past seven and finished at five.

When we got paid on Thursday’s, we used to go over to the Clifton – Thursday was curry day. My friend Adele said ‘I’ll take you to an Indian restaurant.’ At first, she took me to a restaurant near Middlesex Street, near the old toilets. ‘I’ll take you there for a curry,’ she offered, so I said ‘All right’ but when we ate there, I told her, ‘Oh, I don’t like that, Adele.’ The food was too hot.

The following Thursday we went to the Clifton, and on the tables were peppers. Terry, the engineer – big bloke – he said ‘Pam …’ He was going out Adele and had a row with her, they weren’t talking. He said, ‘Pam, it’s no good asking her for a roll …’ So I offered, ‘All right, I’ll get one for you.’ He said, ‘I want cheese and tomato.’ I got him two cheese and tomato rolls, but I took a pepper and took the pips out and put them in with the tomato pips. Then I gave them to him and went home afterwards, because I knew what he would do. I was a bit of a joker. I didn’t worry about anything. Nobody got me down.

My sister was different. She was a worrier. I mean, I went there one day and she was crying her eyeballs out. And they all said to me. ‘Pam, Betty’s crying,’ and I said, ‘What are you crying for?’ So she told me that Yvonne, or whatever her name was, said, ‘We can’t go home in her car if we smoke.’ I said ‘Listen, you don’t need her car. You got a pair of legs. Walk on them. Or get a cab home. Don’t let them get you down.’ Well, all the girls in there, they said ‘Pam, how brave you are, you don’t care.’

I met my partner at Truman’s. He was a student of nineteen and I was forty-eight, they used to take students on at Truman’s at busy times. One day, I was out with Adele and she said,‘Pam, I’m not coming to dinner with you today’ and I went ‘You’re not? Why’s that?’ She said to me ‘A student has asked me to have a drink with him at dinner time.’ I replied, ‘Oh, I see, we’ll see about that’. I went straight over to Bernie and asked, ‘Excuse me, can I speak to you?’ And he said ‘Yes’ and I said ‘Are you taking my friend, Adele, for a drink at dinnertime?’ He said, ‘Yes’ and I said, ‘I don’t think so.’ He said, ‘What?’ and I said again‘I don’t think so.’ He said, ‘Why’s that?’ and I said, ‘If you take her then you’ve got to take me too.’ He went, ‘Oh, alright then, you can come too,’ and I said, ‘Never mind about alright, I’m coming…’

Later, Adele met a student too. Bernie was only nineteen when I met him and I’ve been with him for thirty-eight years. I’ve got four children from my first marriage. My youngest one is sixty-one now. I got one at sixty-one, one at sixty-two, one at sixty-three and the eldest one’s three years older, she’s sixty-six. So I’ve not done bad, bringing up four kids in two rooms. I may be eighty-three but I’m still as lively as if I was twenty-one.

I was brought up in Malta because my father was Maltese. We used to come back and forth, he was a seaman. In the end, he gave up the sea because he had malaria and he was in Addenbrooke’s hospital in Cambridge, where they told him that he could get better treatment in London – so we all moved back to where my mother came from.

There were a lot of Maltese people in the East End then, but they had a very bad name. My husband was Maltese. He was a good husband but he used to hate me talking to bad girls and I’d ask him, ‘Why?’ In Stepney, you’d see the prostitutes, you had them all living in them houses next the hospital where they had furnished rooms. If they saw you with your kids, you don’t say to your child, ‘Don’t talk to her, she’s no good, she’s a so-and-so.’ That’s not me. For me, she’s a human being. Her life is her life. What happened was he said ‘Look Pam, say there’s a crowd of Maltese in Whitechapel’ – which there used to be years ago, they all gathered near the station. He said, ‘You’re not gonna talk to them. I’m being straightforward with you.’ He didn’t want me to get categorised like that or be labelled.

He didn’t want me to work at the bottling plant either, but I done it anyway. See, I’m stubborn. You had every creed, every race. I mean I’m gonna be fair because I have to, I got to swear. When I went in in the morning, I’d say ‘Good Morning, Sweary Mary,’ and she’d say to me ‘F*** off, you Maltese bastard!’

‘You Irish, you Welsh, you Scotch, you Black, you White’ – she’d have a name for every one of one of them. We had Lil, we used to call her ‘Barley-Wine Lil’ because, as soon as she came in, she’d grab a plastic cup. We’d all be thinking she was drinking tea – but she wasn’t! This was seven o’clock in the morning and she was drinking barley wine!

It was very, very good experience for me. I mean, if anything happens to me, I’ve had a good life. I loved the atmosphere, the fighting, and the swearing. And to me, they were straightforward people. Because they’d row with you today and speak to you tomorrow. They didn’t hold it against you. See, I’m a type of person can’t hold rows with people, I just want to be friends, you know.

Once, Me & Adele went down Brick Lane to the market and Sweary Mary was in front of us. We were in our welly boots and our overalls. They had these big stalls down Wentworth Street on a Friday or a Thursday, and we saw Mary – well I tell you what, I’ve never run from nobody. I said to Adele, ‘Look, Sweary Mary’s in front.’ Adele shouts out ‘Sweary Mary!’ Oh, she just turned round and shouted at us ‘F*** off, you Truman’s whores.’ Oh, did we laugh. I mean, it’s not nice really, but that was us. We couldn’t do it today. When you got home you were a different person because you were in your family.

If someone phoned me up and said ‘Pam, there is a permanent vacancy at Truman’s, would you do it?’ The answer’d be, ‘Yes.’ I’d probably go with one leg. You had your ups and downs but there was no violence and – the beer! It was nobody’s business.

Terry, the bloke I gave the peppers to, he was a comedian. It was so hot in the bottling plant that all we had on was our cross-over aprons and our bras and pants. I had a high chair, and I had to grab these cans and pull them forward. One day, he came behind my chair and – this is all because of the pepper in the cheese and tomato roll – I knew he’d get me back, but he didn’t get me straight away. He took my chair and tipped it upside down over a container for old cardboard boxes. He shook me, picking me up and throwing me off my chair into the big container. I couldn’t get out, my friends had to pass me wooden boxes so I could make steps to get out. Well you know, it was dangerous.

Yes, we had a bad name. Like I told you, my husband didn’t want me to go there because of the bad name. But it doesn’t mean to say you’re all the same. Yes, I had a laugh and joke, I’m not saying I didn’t. As I said, that bloke Terry got hold of me, he turned me upside down, my boobs went over my shoulders, and I didn’t think nothing of it. But my husband – to this day – he never knew. I didn’t see harm in it. But no, it was good, I loved it. Honest, I loved it. If it hadn’t closed down, I would still be there. I would probably be the sweeper-up!

My husband died after I left Truman’s but I had already met Bernie, and the marriage was already on the rocks. I left him in the end. I always said, ‘Once my children grow up, I’m off.’ And when my children got married, the last one, I was off. And that is how I met Bernie.

At first, they all thought that he was a policeman and I knew that thieving was going on, pinching beer. So he came in one morning and he had navy trousers on, and Adele said to me, ‘Pam, there’s a policeman in here.’ So I said, ‘What do you mean, a policeman?’ I went to him ‘Oi, are you a policeman?’ and he said, ‘No.’ Of course, when we saw him in the morning, we used to shout, ‘Morning, Officer!’ But it’s true, his father was a police sergeant at Chequers and he grew up there. We always said he was a bit of a snob.

I’m eighty-three and Bernie’ll be fifty-eight this year. We just hit it off, age didn’t make any difference. We clicked from that day we met. And he is good as gold. It was fate. I say to myself, ‘It’s fate you meeting Bernie, he wanted a bottling girl.’ He’s been in a lot of places, Bernie. He met Harold Wilson and – who’s that other prime minister? But that’s another story…”

Pamela Cilia at home in Rainham – ” I’m eighty-three and still as lively as if I was twenty-one.”

Labels courtesy Stephen Killick

Transcript by Jennifer Winkler

You may also like to read these other Truman’s stories

First Brew at the New Truman’s Brewery

Tony Jack, Chauffeur at Truman’s Brewery

A Comic Alphabet

You might like to see other work by George Cruikshank

Jack Sheppard, Thief, Highwayman & Escapologist

The Bloody Romance of the Tower

Henry Mayhew’s Punch & Judy Man

and these other alphabets

Matt Walters, The Human Statue

An unexpected tap on the head in the Spitalfields Market yesterday was enough to convey the joyous news that my pal, Matt Walters the Human Statue, had returned after an absence of several years

Did you ever walk through the Spitalfields Market and feel the lightest touch upon you, as if the ghost of some long-departed market porter were reaching out across time? Very likely that was Matt Walters the Human Statue, who has been standing on a box in the market for the last five years and become the catalyst for the long-running drama that takes place each weekend in the narrow passage between the Creperie and the Rapha Cycle Club.

As visitors arrive in the Spitalfields Market, walking from the new development into the old building and enjoying the historic ambience, including the bronze figure of a man in flat cap, they are sometimes shaken from their reverie by a tap on the head from the living statue. The innocent hilarity thus engendered has become an attraction in its own right and you will regularly find a small crowd assembled here with cameras at the ready to record the never-ending amusement as a stream of unwitting newcomers are bamboozled in similar fashion.

The mysterious and slightly sinister charisma of the human statue is one of enduring fascination to adults and children alike. Most people are more than willing to enter into the light-hearted complicity required, with the rare of exceptions of little ones that become gripped with abject terror and big ones whose dignity is affronted by such unwarranted mischief. Yet, succumbing to the pull myself – like some latter-day Don Giovanni – I arranged a private assignation with the statue and he favoured me by breaking his customary silence.

“My father a was an Orthopaedic Surgeon and General Practitioner, but I left school after I flunked all my O levels. Then I lasted a couple of months studying catering until the craze of robotic dancing came in, and I found I was good at it and I could make a living out of being a robot.

After about ten years of doing that, I saw my first human statue in Paris and by then I’d had enough of being a robot. It was at Fontainbleu and I couldn’t understand why all the French were staring at this statue in a flowerbed, so I went up to touch it and she grabbed me – scared the living daylights out of me! I literally came back and – although I didn’t know how – I decided I was going to do it. I had a booking as a robot at a night club but I turned up and said, ‘I’m going to be a human statue.’ So I got my make-up on and painted myself up and stood in the foyer for two and a half hours and that was that. It didn’t go too well, as the club owner didn’t notice me and thought I’d gone home. But after two and a half hours my calves were killing me, so I dropped the character and stepped off my plinth, and the whole club freaked out – ‘Bloody hell, it’s alive!’

That was fifteen years ago, so I have been doing this for twenty-eight years now. It’s really hard to stand still, it takes a lot of core strength and you have to breathe quite shallowly. I’m looking around for who to pick and you can always tell who’s comfortable by the way they walk towards you. I lower my heartbeat while I’m standing, my pulse goes down to twenty-eight and I feel very relaxed. It nearly killed me in November though, because I had blood clots in my lungs and the doctor said it might be from standing still such a long time. But I am fully recovered and you know, ‘Worse things happen at sea!’ I hope I’ll be doing it for a few years yet, because no-one can see my age under the make-up. The oldest human statue is in the Ramblas in Barcelona – he is seventy-four and he looks like the perfect statue of a wizened old man.

I love what I do and there is the freedom of choosing your hours. Each day, I start at 11:30am and finish about 7:00pm with a few breaks in between. A policeman said to me, ‘Every time you touch someone, technically you are assaulting them.’ but people understand that it’s harmless. I’m very lucky with the comments I get, people say, ‘I’ve never seen anything as good as that.’ I’m at the top of my tree. I’m not begging, I’m a performer and people choose to put money in the tin or not. You always give your best performance and let people take as many photos as they like, whether they give you something or not.

Before the recession, business was really good. I had thirteen people working for me at one time – training them up, breaking them in and teaching them how to apply their make-up. I’d have four or five corporate events each week and at least one wedding each weekend. In the early days, I did the opening of every new Specsavers, that’s three hundred and sixty shops. And I did all the openings for Hotel du Vin too, for a while we were synonymous. It was a successful business until it all came crashing down around me and now I am a solo street entertainer – doing Spitalfields each Sunday, South Bank on Monday, Kingston on Thursday or Friday, and Wimbledon on a Saturday. It all depends where I’m racing – I used to do ultra-marathons but now I do cycle racing. My other passion is bird watching, I’ve seen the Peregrine Falcons at St Paul’s and at the Barbican. Half my ear is listening to birdsong and the other half is listening to people around me – you get so much more attuned when you are silent.

I dress up as a Chimney Sweep generally, but if it gets hot I paint myself white all over like a Sandstone Figure. I only do that if there’s a shower because otherwise it takes six boxes of baby-wipes to remove the make-up. I have great skin because I’m always exfoliating. I do other colours as well, so if there’s a corporate logo I can spray it on my body with a stencil and match up the colour. I also do a Roman Centurion, Stars & Stripes for 4th July, and Verdigris, and I do a Torch Bearer with a real flaming torch for night-time. I don’t wear gold or silver, I make myself up to look like a real bronze statue. I was Planet Hollywood’s human statue at the Trocadero for eight years. I was there for the Olympics and I’m going back for four or five days a week this summer. They regard it as a kind of subliminal advertising because people get involved with my act and then they go into the restaurant.

Nowadays, there’s all these people down in Covent Garden with masks which I regard as cheating. In my time, there used to be the Doggy Man who sat in a cat basket, Duncan the Silver Gladiator and the Leaning Man, who had his shoes nailed to a board and could lean forty-five degrees. There were four of us lined up, so you had to work hard to earn your money but I enjoyed the competition.

I’ve been in Spitalfields for five years. I came here just after it had been redeveloped and I dropped one of my cards off at the market office, and they rang me up and I have been here ever since. When I started, the owner of the cafe came out and said ‘I love what you do, you can have a free coffee in my cafe anytime.’ The security guards are very protective and the stall holders are very friendly too. You’d think people would suss out what I’m doing by now, but there’s always a mass of new people coming through and I’ve had tourists returning each year to find me. The glass roof keeps the rain off and it’s sheltered here, unlike Covent Garden where I was exposed to the cold and snow. I love Spitalfields, it’s a great place to be a statue.”

Matt Walters, Human Statue

Don Giovanni and the Statue by Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard, c. 1830-35.

You can book Matt Walters, the Human Statue, through Mechanical Fracture

You may also like to read about