A Book Of John Claridge’s EAST END

Over the next few days, we shall be featuring John Claridge’s East End photography from the sixties

Perhaps no-one took more photographs in the East End in the sixties than John Claridge? The outcome was a insider’s portrait of an entire society, observed with affection and candour by a distinctive photographic talent.

Click here to order a copy of EAST END by John Claridge for £25

The window on the top right of this photograph was John Claridge’s former bedroom when he took this astonishing portrait of his neighbours in Plaistow – Mr & Mrs Jones – in 1968, on a visit home in his early twenties.

Once, at the age of eight, John saw a plastic camera at a fair on Wanstead Flats and knew he had to have it. And thus, in that intuitive moment of recognition, his lifelong passion for photography was born. Saving up money from his paper round in the London Docks, John bought an Ilford Sport and recorded the world that he knew, capturing the plangent images you see here with a breathtaking clarity of vision. “Photography was a natural language,” he assured me, when I asked him about taking these pictures, “This was my life.”

“My father was a docker – everyone worked in the docks, did a bit of boxing or they were villains. My dad went to sea when he was thirteen, he did bare-knuckle boxing, he knew how to rig a ship from top to bottom, and he sold booze in the states during prohibition. I used to get up at five in the morning to talk to him before he went to work and he told me stories, that was my education. People say life was hard in the East End, but I found the living was easy and I loved it.”

With admirable self-assurance, John left school at fifteen and informed West Ham Labour Exchange of his chosen career. They sent him up to the McCann-Erickson advertising agency in the West End where he immediately acquired employment in the photographic department. Then, at seventeen years old, John bravely travelled from Plaistow to Hampstead to knock on the door of Bill Brandt to present one of his prints, and the legendary photographer invited him in, recognising his precocious talent and offering encouragement to the young man.

“I used to meet my mum after work in the Roman Rd where she was a machinist, and you couldn’t see the next street in the fog,” John recalled, when I enquired about the distinctive quality of light in these atmospheric images. At the age of nineteen, John left the East End for good and at the same time opened his first studio near St Paul’s Cathedral. It was the precursor an heroic career in photography which has seen John working at the top of his profession for decades, yet he still carries a deep affection for these eloquent haunting pictures that set him on his way. “My East End’s gone, it doesn’t exist anymore,” he admitted to me frankly with unsentimental discernment, “These are pictures I could never do again, I don’t have that naivety and innocence anymore, but seeing them now is like looking at an old friend.”

Collecting firewood, 1960

1961

1963

1966

1972

1960

Ex-boxer, 1962

1974

1962

1961

Mass X-Ray, 1966

1962

1960

Flower Seller, 1959

1962

Shoe Rebuilders, 1965

London fog, 1959

Going to work, 1959

London Docks, 1964

Photographs copyright © John Claridge

Click here to order a copy of John Claridge’s EAST END for £25

Merlin The Raven At The Tower Of London

Chris Skaife & Merlin

Every day at first light, Chris Skaife, Master Raven Keeper at the Tower of London, awakens the ravens from their slumbers and feeds them breakfast. It is one of the lesser known rituals at the Tower, so Contributing Photographer Martin Usborne & I decided to pay an early morning call upon London’s most pampered birds and send you a report.

The keeping of ravens at the Tower is a serious business, since legend has it that, ‘If the ravens leave the Tower, the kingdom will fall…’ Fortunately, we can all rest assured thanks to Chris Skaife who undertakes his breakfast duties conscientiously, delivering bloody morsels to the ravens each dawn and thereby ensuring their continued residence at this most favoured of accommodations.“We keep them in night boxes for their own safety,” Chris explained to me, just in case I should think the ravens were incarcerated at the Tower like those monarchs of yore, “because we have quite a lot of foxes that get in through the sewers at night.”

First thing, Chris unlocks the bird boxes built into the ancient wall at the base of the Wakefield Tower and, as soon as he opens each door, a raven shoots out blindly like a bullet from a gun, before lurching around drunkenly on the lawn as its eyes accustom to the daylight, brought to consciousness by the smell of fresh meat. Next, Chris feeds the greedy brother ravens Gripp – named after Charles Dickens’ pet raven – & Jubilee – a gift to the Queen on her Diamond Anniversary – who share a cage in the shadow of the White Tower.

Once this is accomplished, Chris walks over to Tower Green where Merlin the lone raven lives apart from her fellows. He undertakes this part of the breakfast service last, because there is little doubt that Merlin is the primary focus of Chris’ emotional engagement. She has night quarters within the Queen’s House, once Anne Boleyn’s dwelling, and it suits her imperious nature very well. Ravens are monogamous creatures that mate for life but, like Elizabeth I, Merlin has no consort. “She chose her partner, it’s me,” Chris assured me in a whisper, eager to confide his infatuation with the top bird, before he opened the door to wake her. Then, “It’s me!” he announced cheerily to Merlin but, with suitably aristocratic disdain, she took her dead mouse from him and flounced off across the lawn where she pecked at her breakfast a little before burying it under a piece of turf to finish later, as is her custom.

“The other birds watch her bury the food, then lift up the turf and steal it,” Chris revealed to me as he watched his charge with proprietorial concern, “They are scavengers by nature, and will hunt in packs to kill – not for fun but to eat. They’ll attack a seagull and swing it round but they won’t kill it, gulls are too big. They’ll take sweets, crisps and sandwiches off children, and cigarettes off adults. They’ll steal a purse from a small child, empty it out and bury the money. They’ll play dead, sun-bathing, and a member of the public will say, ‘There’s a dead raven,’ and then the bird will get up and walk away. But I would not advise any members of the public to touch them, they have the capacity to take off a small child’s finger – not that they have done, yet.”

We walked around to the other side of the lawn where Merlin perched upon a low rail. Close up, these elegant birds are sleek as seals, glossy black, gleaming blue and green, with a disconcerting black eye and a deep rasping voice. Chris sat down next to Merlin and extended his finger to stroke her beak affectionately, while she gave him some playful pecks upon the wrist.

“Students from Queen Mary University are going to study the ravens’ behaviour all day long for three years.” he informed me, “There’s going to be problem-solving for ravens, they’re trying to prove ravens are ‘feathered apes.’ We believe that crows, ravens and magpies have the same brain capacity as great apes. If they are a pair, ravens will mimic each other’s movements for satisfaction. They all have their own personalities, their moods, and their foibles, just like people.”

Then Merlin hopped off her perch onto the lawn where Chris followed and, to my surprise, she untied one of Chris’s shoelaces with her beak, tugging upon it affectionately and causing him to chuckle in great delight. While he was thus entrammelled, I asked Chris how he came to this role in life. “Derrick Coyle, the previous Master Raven Keeper, said to me, ‘I think the birds will like you.’ He introduced me to it and I’ve been taking care of them ever since.“ Chris admitted plainly, opening his heart, “The ravens are continually on your mind. It takes a lot of dedication, it’s early starts and late nights – I have a secret whistle which brings them to bed.”

It was apparent then that Merlin had Chris on a leash which was only as long as his shoelace. “If one of the other birds comes into her territory, she will come and sit by me for protection,” he confessed, confirming his Royal romance with a blush of tender recollection, “She sees me as one of her own.”

“Alright you lot, up you get!”

“A pigeon flew into the cage the other day and the two boys got it, that was a mess.”

“It’s me!”

“She chose her partner, it’s me.”

“She sees me as one of her own.”

Chris Skaife & Merlin

Charles Dickens’ Raven “Grip” – favourite expression, “Halloa old girl!”

Tower photographs copyright © Martin Usborne

Residents of Spitalfields and any of the Tower Hamlets may gain admission to the Tower of London for one pound upon production of an Idea Store card.

You may also like to take a look at these other Tower of London stories

Alan Kingshott, Yeoman Gaoler at the Tower of London

Graffiti at the Tower of London

Beating the Bounds at the Tower of London

Ceremony of the Lilies & Roses at the Tower of London

Bloody Romance of the Tower with pictures by George Cruickshank

John Keohane, Chief Yeoman Warder at the Tower of London

Constables Dues at the Tower of London

The Oldest Ceremony in the World

A Day in the Life of the Chief Yeoman Warder at the Tower of London

The Broderers Of St Paul’s Cathedral

Anita Ferrero

Like princesses from a fairy tale, the Broderers of St Paul’s sit high up in a tower at the great cathedral stitching magnificent creations in their secret garret and, recently, Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I climbed up one hundred and forty-one steps to pay a visit upon these nimble-fingered needleworkers.

‘There are fourteen of us, we chat, we tell stories and we eat chocolate,’ explained Anita Ferrero by way of modest introduction, as I stood dazzled by the glittering robes and fine embroidery. ‘It’s very intense work because the threads are very bright,’ she added tentatively, lest I should think the chocolate comment revealed undue levity.

I was simply astonished by the windowless chamber filled with gleaming things. ‘There are thirteen tons of bells suspended above us,’ Anita continued with a smile, causing me to cast my eyes to the ceiling in wonder, ‘but it’s a lovely sound that doesn’t trouble us at all.’

Observing my gaze upon the magnificent textiles, Anita drew out a richly-embellished cope from Queen Victoria’s Jubilee. ‘This is cloth of gold’ she indicated, changing her voice to whisper, ‘it ceased production years ago.’

‘There are still wonderful haberdashers in Kuala Lumpur and Aleppo,’ she informed me as if it were a closely-guarded secret, ‘I found this place there that still sold gold thread. If someone’s going to Marrakesh, we give them a shopping list in case they stumble upon a traditional haberdashery.’ Next, Anita produced a sombre cope from Winston Churchill’s funeral, fashioned from an inky black brocade embroidered with silver trim, permitting my eye to accommodate to the subtler tones that can be outshone by tinsel.

In this lofty chamber high above the chaos of the city, an atmosphere of repose prevails in which these needlewomen pursue their exemplary work in a manner unchanged over millennia. I was in awe at their skill and their devotion to their art but Anita said, ‘As embroiderers, we are thankful to have a purpose for our embroidery because there’s only so many cushions you can do.’

I walked over to a quiet corner where Rachel Rice was stitching an intricate border in gold thread. ‘I learnt my skills from my mother and grandmother, and I always enjoyed sewing and dressmaking but that’s not fine embroidery like this,’ she admitted, revealing the satisfaction of one who has spent a life devoted to needlework. Yet she qualified her pride in her craft by admitting her humanity with a weary shrug, ‘Some of the work is extremely tedious and it’s never seen.’

‘We are all very expert but our eyesight is fading and a few of us are quite elderly,’ confided Anita, thinking out loud for the two of them as she picked up the story and exchanged a philosophical grin with Rachel. Nowhere in London have I visited a sanctum quite like the Broderers chamber or encountered such self-effacing creative talents.

‘We not so isolated up here,’ emphasised Anita, lifting the mood with renewed enthusiasm, ‘Most people who work in the Cathedral know we’re here. We often do favours for members of staff, taking up trouser hems etc – consequently, if we have a problem, we can call maintenance and don’t have to wait long.’

I was curious to learn of the Broderers’ current project, the restoration of a banner of St Barnabas. ‘He’s the one saint I’d like to meet because he’s called ‘The Son of Encouragement’ – he looks like a nice guy,’ confessed Anita fondly, laying an affectionate hand upon the satin, ‘We’re restoring the beard of St Barnabas at present and we’re getting Simon the good-looking Virger up here to photograph his beard.’

Rachel Rice – ‘I learnt my skills from my mother and grandmother’

Sophia Sladden

Margaret Gibberd

‘As embroiderers, we are thankful to have a purpose for our embroidery because there’s only so many cushions you can do.’

Judy Hardy

‘We chat, we tell stories and we eat chocolate..’

Virger Simon Brears is the model for the beard of St Barnabas

View from the Triforium

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may catch a glimpse of the Broderers for yourself by taking a Triforium Tour at St Paul’s Cathedral. Additionally, there are occasionally opportunities to join the Broderers, so if you have embroidery, dressmaking or mending skills, please email khart@stpaulscathedral.org.uk

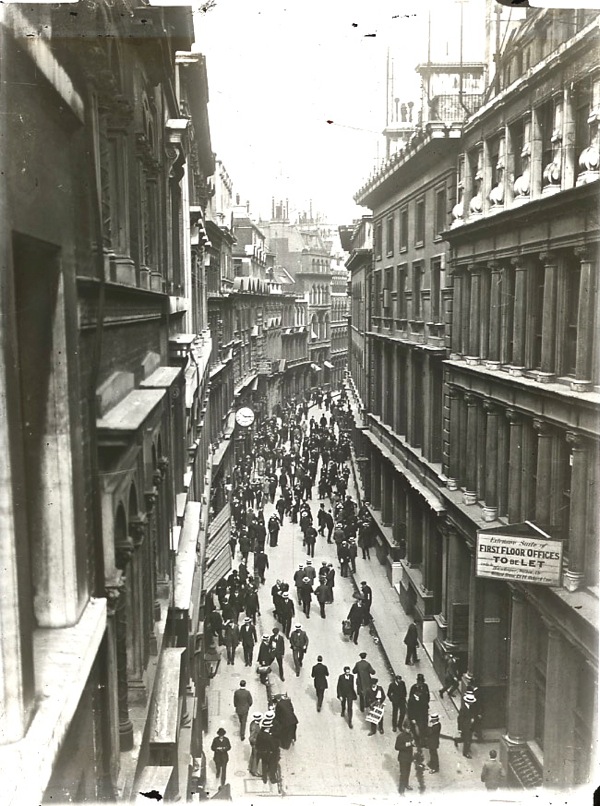

Streets Of Old London

Piccadilly, c. 1900

In my mind, I live in old London as much as I live in the contemporary London of here and now. Maybe I have spent too much time looking at old photographs – such as these glass slides once used for magic lantern shows by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society at the Bishopsgate Institute?

Old London exists to me through photography almost as vividly as if I had actual memory of a century ago. Consequently, when I walk through the streets of London today, I am especially aware of the locations that have changed little over this time. And, in my mind’s eye, these streets of old London are peopled by the inhabitants of the photographs.

Yet I am not haunted by the past, rather it is as if we Londoners in the insubstantial present are the fleeting spirits while – thanks to photography – those people of a century ago occupy these streets of old London eternally. The pictures have frozen their world forever and, walking in these same streets today, my experience can sometimes be akin to that of a visitor exploring the backlot of a film studio long after the actors have gone.

I recall my terror at the incomprehensible nature of London when I first visited the great metropolis from my small city in the provinces. But now I have lived here long enough to have lost that diabolic London I first encountered in which many of the great buildings were black, still coated with soot from the days of coal fires.

Reaching beyond my limited period of residence in the capital, these photographs of the streets of old London reveal a deeper perspective in time, setting my own experience in proportion and allowing me to feel part of the continuum of the ever-changing city.

Ludgate Hill, c. 1920

Holborn Viaduct, c. 1910

Trinity Almshouses, Mile End Rd, c. 1920

Throgmorton St, c. 1920

Highgate Forge, Highgate High St, 1900

Bangor St, Kensington, c. 1900

Ludgate Hill, c. 1910

Walls Ice Cream Vendor, c. 1920

Ludgate Hill, c. 1910

Strand Yard, Highgate, 1900

Eyre St Hill, Little Italy, c. 1890

Eyre St Hill, Little Italy, c. 1890

Muffin man, c. 1910

Seven Dials, c. 19o0

Fetter Lane, c. 1910

Piccadilly Circus, c. 1900

St Clement Danes, c. 1910

Hoardings in Knightsbridge, c. 1935

Wych St, c.1890

Dustcart, c. 1910

At the foot of the Monument, c. 1900

Pageantmaster Court, Ludgate Hill, c. 1930

Pageantmaster Court, Ludgate Hill, c. 1930

Holborn Circus, 1910

Cheapside, 1890

Cheapside ,1892

Cheapside with St Mary Le Bow, 1910

Regent St, 1900

Glass slides courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

At The RHS Spring Flower Show

There may yet be another month before spring begins, but inside the Royal Horticutural Hall in Victoria it arrived with a vengeance yesterday. The occasion was the RHS Plant & Design Show held each year at this time, which gives specialist nurseries the opportunity to display a prime selection of their spring-flowering varieties and introduce new hybrids to the gardening world.

I joined the excited throng at opening time on the first day, entering the great hall where shafts of dazzling sunshine descended to illuminate the woodland displays placed strategically upon the north side to catch the light. Each one a miracle of horticultural perfection, it was as if sections of a garden had been transported from heaven to earth. Immaculate plant specimens jostled side by side in landscapes unsullied by weed, every one in full bloom and arranged in an aesthetic approximation of nature, complete with a picturesque twisted old gate, a slate path and dead beech leaves arranged for pleasing effect.

Awestruck by rare snowdrops and exotic coloured primroses, passionate gardeners stood in wonder at the bounty and perfection of this temporary arcadia, and I was one of them. Let me confess I am more of a winter gardener than of any other season because it touches my heart to witness those flowers that bloom in spite of the icy blast. I treasure these harbingers of the spring that dare to show their faces in the depths of winter and so I found myself among kindred spirits at the Royal Horticultural Hall.

Yet these flowers were not merely for display, each of the growers also had a stall where plants could be bought. Clearly an overwhelming emotional occasion for some, “It’s like being let loose in a sweet shop,” I overhead one horticulturalist exclaim as they struggled to retain self-control, “but I’m not gong to buy anything until I have seen everything.” Before long, there were crowds at at each stall, inducing first-day-of-the-sales-like excitement as aficionados pored over the new varieties, deliberating which to choose and how many to carry off. It would be too easy to get seduced by the singular merits of that striped blue primula without addressing the question of how it might harmonise with the yellow primroses at home.

For the nurserymen and women who nurtured these prized specimens in glasshouses and poly-tunnels through the long dark winter months, this was their moment of consummation. Double-gold-medal-winner Catherine Sanderson of ‘Cath’s Garden Plants’ was ecstatic – “The mild winter has meant this is the first year we have had all the colours of primulas on sale,” she assured me as I took her portrait with her proud rainbow display of perfect specimens.

As a child, I was fascinated by the Christmas Roses that flowered in my grandmother’s garden in this season and, as a consequence, Hellebores have remained a life-long favourite of mine. So I was thrilled to carry off two exotic additions to a growing collection which thrive in the shady conditions of my Spitalfields garden – Harvington Double White Speckled and Harvington Double White.

Unlike the English seasons, this annual event is a reliable fixture in the calendar and you can guarantee I shall be back at the Royal Horticultural Hall next year, secure in my expectation of a glorious excess of uplifting spring flowers irrespective of the weather.

Double-gold-medal-winner Catherine Sanderson of ‘Cath’s Garden Plants’

You may also like to read about

Bob Mazzer, Tube Photographer

We are proud to announce that Bob Mazzer, Tube Photographer Extraordinaire who first found fame here in the pages of Spitalfields Life, is back with an exhibition which opened yesterday at the Leica Gallery at the Royal Exchange in the City of London and runs until March 11th.

“There’s definitely a link between being born in Aldgate and taking all these pictures on the tube,” Bob admitted to me, “You don’t think you are starting a project, but one day you look back over your recent pictures and there are a dozen connected images, and you realise it is the beginning of a project – and then you fall in love with it.”

“For a while in the eighties, I lived with my father in Manor House and worked as a projectionist at a porn cinema in Kings Cross. It was called The Office Cinema, so guys could call their wives and say, ‘I’m still at the office'” recalled Bob affectionately, “Every day, I travelled to Kings Cross and back. Coming home late at night, it was like a party and I felt the tube was mine and I was there to take pictures.”

Photographs copyright © Bob Mazzer

You may also like to take a look at

Beigels Already

Debbie Shuter’s short film ‘Beigels Already’ was shot at Brick Lane Beigel Bakery in 1992. Watch out for appearances by some familiar local characters, including Mr Sammy looking youthful and sassy.

You may also like to read about