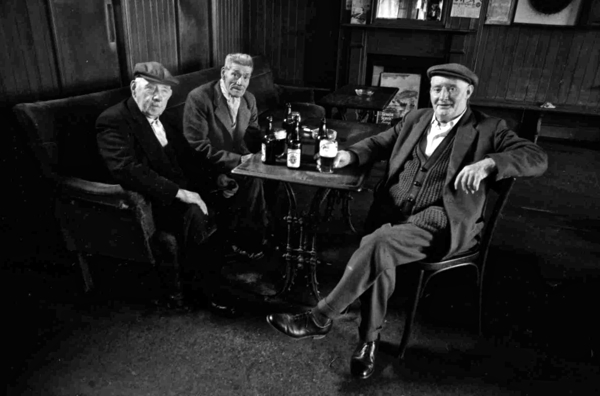

Tony Hall’s Pub Photography

Libby Hall remembers the first time she visited a pub with Tony Hall in the nineteen sixties – because it signalled the beginning of their relationship which lasted until his death in 2008. “We’d been working together at a printer in Cowcross St, Clerkenwell, but our romance began in the pub on the night I was leaving,” Libby confided to me, “It was my going-away drinks and I put my arms around Tony in the pub.”

During the late sixties, Tony Hall worked as a newspaper artist in Fleet St for The Evening News and then for The Sun, using his spare time to draw weekly cartoons for The Labour Herald. Yet although he did not see himself as a photographer, Tony took over a thousand photographs that survive as a distinctive testament to his personal vision of life in the East End.

Shift work on Fleet St gave Tony free time in the afternoon that he spent in the pub which was when these photographs, published here for the first time, were taken. “Tony loved East End pubs,” Libby recalled fondly, “He loved the atmosphere. He loved the relationships with the regular customers. If a regular didn’t turn up one night, someone would go round to see if they were alright.”

Tony Hall’s pub pictures record a lost world of the public house as the centre of the community in the nineteen sixties. “On Christmas 1967, I was working as a photographer at the Morning Star and on Christmas Eve I bought an oven-ready turkey at Smithfield Market.” Libby remembered, “After work, Tony and I went into the Metropolitan Tavern, and my turkey was stolen – but before I knew it there had been a whip round and a bigger and better one arrived!”

The former “Laurel Tree” on Brick Lane

Photographs copyright © Libby Hall

Images Courtesy of the Tony Hall Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute

Libby Hall & I would be delighted if any readers can assist in identifying the locations and subjects of Tony Hall’s photographs.

You may also like to read

March’s New Cries Of London

Even though it is nine months since my CRIES OF LONDON book came out, yet I still cannot resist collecting more, especially when they are as appealing as those in this lovingly-handmade booklet from the early nineteenth century that I acquired for just a couple of pounds recently. The street names in the background of these images fascinate me, and I wonder if that is ‘White Hart Court’ Bishopsgate, in the first picture?

CLICK TO BUY A SIGNED COPY OF THE CRIES OF LONDON FOR £20

You may like to explore these sets of Cries of London

More John Player’s Cries of London

More Samuel Pepys’ Cries of London

Geoffrey Fletcher’s Pavement Pounders

William Craig Marshall’s Itinerant Traders

H.W.Petherick’s London Characters

John Thomson’s Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana II

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana III

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

Music Hall Stars Of Abney Park Cemetery

When the summer heat hits the city and the streets get dusty and dry, I like to seek refuge in the green shade of a cemetery. Commonly, I visit Bow Cemetery – but recently I went along to explore Abney Park Cemetery in Stoke Newington to find the graves of the Music Hall Artistes resting there.

John Baldock, Cemetery Keeper, led me through the undergrowth to show me the memorials restored by the Music Hall Guild and then left me to my own devices. Alone in the secluded leafy glades of the overgrown cemetery with the Music Hall Artistes, I swore I could hear distant singing accompanied by the tinkling of heavenly ivories.

George Leybourne, Songwriter, Vocalist and Comedian, also known as Champagne Charlie (1842 – 1884) & Albert Chevalier (1861- 1923), Coster Comedian and Actor. Chevalier married Leybourne’s daughter Florrie and they all rest together.

George Leybourne – “Champagne Charlie is my name, Champagne Charlie is my name ,There’s no drink as good as fizz, fizz, fizz, I’ll drink every drop there is, is, is!”

Albert Chevalier – “We’ve been together now for forty years, An’ it don’t seem a day too much, There ain’t a lady livin’ in the land, As I’d swop for my dear old Dutch.”

G W Hunt (1838 – 1904) Composer and Songwriter, his most famous works were “MacDermott’s War Song” (The Jingo Song), “Dear Old Pals” and “Up In A Balloon” for George Leybourne and Nelly Power.

G W Hunt

Fred Albert George Richard Howell (1843 – 1886) Songwriter and Extempore Vocalist

Fred Albert

Dan Crawley (1871 – 1912) Comedian, Vocalist, Dancer and Pantomime Dame rests with his wife Lilian Bishop, Actress and Male Impersonator. He made his London debut at nineteen at Royal Victor Theatre, Victoria Park, and for many years performed three shows a day on the sands at Yarmouth, where he met his wife.They married in Hackney in 1893 and had four children, and toured together as a family, including visiting Australia, before they both died at forty-one years old.

Dan Crawley

Herbert Campbell (1844 – 1904) Comedian and Pantomime Star. The memorial behind the tombstone was erected by a few of his friends. Herbert Campbell played the Dame in Pantomime at Drury Lane for forty years alongside Dan Leno, until his death at at sixty-one.

Herbert Campbell, famous comedian and dame of Drury Lane

Walter Laburnum George Walter Davis (1847 – 1902) Singer, Patter Vocalist and Songwriter

Walter Laburnum

Nelly Power Ellen Maria Lingham (1854 – 1887) started her theatrical career at the age of eight, and was a gifted songstress and exponent of the art of male impersonation. Her most famous song was ‘The Boy I Love Is Up In The Gallery.” She died from pleurisy on 19th January 1887, aged just thirty-two.

Nelly Power – Vesta Tilley was once her understudy

The Music Hall Guild host a free guided walk through Abney Park Cemetery to visit the Music Hall Artistes on the last Saturday of each month – meet at the gates at 2pm

At The Still & Star

Still & Star, 1 Little Somerset St, Aldgate

There is very little left of old Aldgate these days – though the Still & Star, just opposite the tube station yet hidden down Little Somerset St, is a rare survivor. This tiny pub on the corner of two alleys is believed to be unique in the City of London as the sole example of what is sometimes described as a ‘slum pub’ – in other words, a licensed premises converted from a private house.

If it would interest you to visit this cosy characterful pub, which almost alone carries the history of this place, you had better do so soon because the City of London are currently considering an application to demolish it to for a huge new office development and, in the meantime, the premises are on the three-month lease.

Current landlord Michael Cox explained to me that the block once contained eight butcher’s shops which were all bought up by one owner, who opened the pub in 1820. Before it was renamed Little Somerset St, the passageway leading to the pub was ‘Harrow Alley’ but colloquially known as ‘Blood Alley.’ At that time, the City of London charged a tariff for driving cattle across the square mile and, consequently, a thriving butchery trade grew up in Aldgate and Whitechapel, slaughtering cattle before the carcasses were transported over to Smithfield.

There is no other ‘Still & Star’ anywhere else – the name is unique to this establishment – and Michael Cox told me the pub originally had its own still, which was housed in the hayloft above, while ‘star’ refers to the Star of David, witnessing the Jewish population of Aldgate in the nineteenth century.

Unfortunately this early nineteenth century building is not listed or in a Conservation Area which does not bode well for its preservation, but you can see the Planning Application on the City of London website which includes an option for anyone who wishes to object to the demolition. Click here to see details of the Planning Application and make a comment.

All around us, pubs are being shut down and demolished yet, as regular readers will know, I have a particular affection for these undervalued institutions which I consider an integral part of our culture and history – necessary oases of civility in the chaos of the urban environment.

Still & Star, 1951 (Courtesy Heritage Assets/The National Brewery Centre)

Still & Star, 1968 (Courtesy Heritage Assets/The National Brewery Centre)

Still & Star today

Harrow Alley by Gustave Dore, 1880

Butcher’s shop at the corner of Harrow Alley (known as Blood Alley) leading through to the Still & Star

Map of 1890 shows the Still & Star with nearby butcher’s shops and slaughterhouses

Charringtons’ record of the landlords (Courtesy Heritage Assets/The National Brewery Centre)

The office block that is proposed to replace the Still & Star, although the developers are offering to have a bar of that name within the new building

You may also like to read about

The Departure Of Viscountess Boudica

Boudica & Boudica

By the time you read this, the Viscountess Boudica will already be gone – taken her leave from London forever and slipped away from Bethnal Green early on Tuesday morning in a van loaded with her possessions – driving up the Great North Road towards her new home in Uttoxeter.

Before she left, I accompanied the Viscountess upon a last sentimental pilgrimage to the statue of her namesake in Westminster and, on the train back to Whitechapel, she explained to me the circumstances of her departure.

Viscountess Boudica arrived at her council flat in Bethnal Green on January 31st 2002 and she remembers it clearly. ‘A friend with a van helped me move from Poplar and we arrived at 10pm. The previous tenant had died in the flat, leaving piles of rubbish and hole in the plaster,’ she recalled, ‘While we moving in, they smashed the windows of my friend’s van and, after three days, I started receiving hate mail telling me to leave.’

Yet in spite of this inauspicious beginning, the Viscountess painted her flat pink and created a life for herself, becoming celebrated as a trendsetter for her flamboyant colourful outfits which made her popular among the crowds at Brick Lane Market. When I met the Viscountess six years ago in Cheshire St and began publishing interviews with her, I was shocked to learn of the frequent violence that the Viscountess received walking around the streets of the East End.

‘I’m not the kind of person that gives in,’ the Viscountess admitted to me then, ‘I find each area is different, you can’t ascertain in advance whether you’ll get mugged or chased, but you only have one life and you have to live it as you think fit. The kids abuse me and the police are useless, so I have to take care of myself. You have to stand up to them. They say they don’t like how I look, and I tell them, ‘If you don’t like it you can put up with it,’ because I’ve been through so much that I’m not going to be persecuted anymore.”

I will never forget the time she changed her name to Viscountess Boudica Denvorgilla Veronica Scarlet Redd by deed poll and persuaded me to fill out the section in her passport application form, vouching for the veracity of her new identity. It was an unlikely collaboration we enjoyed over the course of more than twenty stories I wrote, photographed and published in these pages, documenting the Viscountess’ seasonal celebrations, recording her remarkable collection of domestic appliances and her coloured outfits – all of which have now been destroyed. I shall miss visiting the pink flat in Bethnal Green to undertake interviews at the court of Viscountess Boudica and encountering her irrepressible courage and good humour, which always sent me away in a buoyant mood. She never failed to astonish me with her originality of thought.

In the end, it was not antipathy and prejudice which drove Viscountess Boudica out of Bethnal Green but a combination of welfare policy and bureaucratic indifference. Like thousands of others, she had her benefits reassessed recently, accompanied by a demand for repayment of money already paid out. The Viscountess found herself in debt and without income, yet facing demands for payment. Any possibility of resolving this mess disappeared when the powers-that-be lost her paperwork. Instead, the Viscountess received a Court Summons for non-payment of Council Tax and Eviction Notices for rent arrears. In the midst of this, she told me the council decided to increase the rent of her one bedroom flat from £100 a week to the ‘market value’ of £700 a week.

The crunch came with a burglary this spring when intruders trashed her flat and destroyed her bed, leaving the Viscountess sleeping on a chair for months. No wonder she asked to be transferred elsewhere and, when a bedsit near Uttoxeter in Staffordshire was offered at £68 a week, she leapt at the opportunity.

‘If you stay in a place too long, it becomes over-familiar,’ she informed me, summoning Dutch courage as we sat in her empty flat last week, ‘I feel there are no more opportunities for me here, but Uttoxeter is a large place with a lot of different people and it will be a new challenge. There will be a period of adjustment but adventures feed the imagination.’

‘I was overcome by people’s generosity,’ she confessed, referring to the online fundraising campaign, as we made our farewells, ‘I’d like to thank all the readers of Spitalfields Life for their emotional support and financial help. If anyone would like me to do them a drawing, send me an email and I will do it for them…’

The East End will be a lesser place without Viscountess Boudica, a kind soul who discovered bravery in the face of cruelty and became a neighbourhood dandy we were all proud to know.

You can contact Viscountess Boudica direct at boudicaredd@gmail.com

‘As they said to me in Islington when they saw my outfit, ‘There’s not a lot of people that’s got the courage.’’

‘I tried going out in Bethnal Green and the reaction was very hostile – from children who threw bottles at me – but I thought, ‘I’ll persevere because fashion is too drab and life should be full of colour.’’

Be sure to follow Viscountess Boudica’s blog There’s More To Life Than Heaven & Earth

You may like to take a look at

Viscountess Boudica’s Domestic Appliances

Viscountess Boudica’s Drawings

Viscountess Boudica’s Halloween

Viscountess Boudica’s Christmas

Viscountess Boudica’s Valentine’s Day

Read my original profile of Mark Petty, Trendsetter

and take a look at Mark Petty’s Multicoloured Coats

Mayhew’s Street Traders

The Long-Song Seller

There is a silent ghost who accompanies me in my work, following me down the street and sitting discreetly in the corner while I am doing my interviews. He is always there in the back of my mind. He is Henry Mayhew, whose monumental work,’London Labour & London Poor,’ was the first to give working people the chance to speak in their own words. I often think of him, and the ambition and quality of his work inspires me. And I sometimes wonder what it was like for him, pursuing his own interviews, one hundred and fifty years ago, in a very different world.

Mayhew’s interviews and pen portraits appeared in the London Chronicle and were published in two volumes in 1851, eventually reaching their final form in five volumes published in 1865. In his preface, Mayhew described it as “the first attempt to publish the history of the people, from the lips of the people themselves – giving a literal description of their labour, their earnings, their trials and their sufferings in their own unvarnished language.”

These works were produced before photography was widely used to illustrate books, and although photographer Richard Beard produced a set of portraits to accompany Mayhew’s interviews, these were reproduced by engraving. Fortunately, since Beard’s photographs have not survived, the engravings were skillfully done. And they are fascinating images, because they exist as the bridge between the popular prints of the Cries of London that had been produced for centuries and the development of street photography, initiated by JohnThomson’s “Street Life in London” in 1876.

Primarily, Mayhew’s intention was to create a documentary record, educating his middle class readers about the lives of the poor to encourage social change. Yet his work transcends the tragic politics of want and deprivation that he set out to address, because the human qualities of his subjects come alive on the page and command our respect. Henry Mayhew bears witness not only to the suffering of poor people in nineteenth century London, but also to their endless resourcefulness and courage in carving out lives for themselves in such unpromising circumstances.

The Oyster Stall. “I’ve been twenty years and more, perhaps twenty-four, selling shellfish in the streets. I was a boot closer when I was young, but I had an attack of rheumatic fever, and lost the use of my hands for my trade. The streets hadn’t any great name, as far as I knew, then, but as I couldn’t work, it was just a choice between street selling and starving, so I didn’t prefer the last. It was reckoned degrading to go into the streets – but I couldn’t help that. I was astonished at my success when I first began, I made three pounds the first week I knew my trade. I was giddy and extravagant. I don’t clear three shillings a day now, I average fifteen shillings a week the year through. People can’t spend money in shellfish when they haven’t got any.”

The Irish Street-Seller. “I was brought over here, sir, when I was a girl, but my father and mother died two or three years after. I was in service, I saved a little money and got married. My husband’s a labourer, he’s out of worruk now, and I’m forced to thry and sill a few oranges to keep a bit of life in us, and my husband minds the children. Bad as I do, I can do a penny or tuppence a day better profit than him, poor man! For he’s tall and big, and people thinks, if he goes round with a few oranges, it’s just from idleniss.”

The Groundsel Man. “I sell chickweed and grunsell, and turfs for larks. That’s all I sell, unless it’s a few nettles that’s ordered. I believe they’re for tea, sir. I gets the chickweed at Chalk Farm. I pay nothing for it. I gets it out of the public fields. Every morning about seven I goes for it. I’ve been at business about eighteen year. I’m out till about five in the evening. I never stop to eat. I am walking ten hours every day – wet and dry. My leg and foot and all is quite dead. I goes with a stick.”

The Baked Potato Man. “Such a day as this, sir, when the fog’s like a cloud come down, people looks very shy at my taties. They’ve been more suspicious since the taty rot. I sell mostly to mechanics, I was a grocer’s porter myself before I was a baked taty. Gentlemen does grumble though, and they’ve said, “Is that all for tuppence?” Some customers is very pleasant with me, and says I’m a blessing. They’re women that’s not reckoned the best in the world, but they pays me. I’ve trusted them sometimes, and I am paid mostly. Money goes one can’t tell how, and ‘specially if you drinks a drop as I do sometimes. Foggy weather drives me to it, I’m so worritted – that is, now and then, you’ll mind, sir.”

The London Coffee Stall. “I was a mason’s labourer, a smith’s labourer, a plasterer’s labourer, or a bricklayer’s labourer. I was for six months without any employment. I did not know which way to keep my wife and child. Many said they wouldn’t do such a thing as keep a coffee stall, but I said I’d do anything to get a bit of bread honestly. Years ago, when I as a boy, I used to go out selling water-cresses, and apples, and oranges, and radishes with a barrow. I went to the tinman and paid him ten shillings and sixpence (the last of my savings, after I’d been four or five months out of work) for a can. I heard that an old man, who had been in the habit of standing at the entrance of one of the markets, had fell ill. So, what do I do, I goes and pops onto his pitch, and there I’ve done better than ever I did before.”

Coster Boy & Girl Tossing the Pieman. To toss the pieman was a favourite pastime with costermonger’s boys. If the pieman won the toss, he received a penny without giving a pie, if he lost he handed it over for nothing. “I’ve taken as much as two shillings and sixpence at tossing, which I shouldn’t have done otherwise. Very few people buy without tossing, and boys in particular. Gentlemen ‘out on the spree’ at the late public houses will frequently toss when they don’t want the pies, and when they win they will amuse themselves by throwing the pies at one another, or at me. Sometimes I have taken as much as half a crown and the people of whom I had the money has never eaten a pie.”

The Street- Seller of Nutmeg Graters. “Persons looks at me a good bit when I go into a strange place. I do feel it very much, that I haven’t the power to get my living or to do a thing for myself, but I never begged for nothing. I never thought those whom God had given the power to help themselves ought to help me. My trade is to sell brooms and brushes, and all kinds of cutlery and tinware. I learnt it myself. I was never brought up to nothing, because I couldn’t use my hands. Mother was a cook in a nobleman’s family when I was born. They say I was a love child. My mother used to allow so much a year for my schooling, and I can read and write pretty well. With a couple of pounds, I’d get a stock, and go into the country with a barrow, and buy old metal, and exchange tinware for old clothes, and with that, I’m almost sure I could make a decent living.”

The Crockery & Glass Wares Street-Seller. “A good tea service we generally give for a left-off suit of clothes, hat and boots. We give a sugar basin for an old coat, and a rummer for a pair of old Wellington boots. For a glass milk jug, I should expect a waistcoat and trowsers, and they must be tidy ones too. There is always a market for old boots, when there is not for old clothes. I can sell a pair of old boots going along the streets if I carry them in my hand. Old beaver hats and waistcoats are worth little or nothing. Old silk hats, however, there’s a tidy market for. There is one man who stands in Devonshire St, Bishopsgate waiting to buy the hats of us as we go into the market, and who purchases at least thirty a week. If I go out with a fifteen shilling basket of crockery, maybe after a tidy day’s work I shall come home with a shilling in my pocket and a bundle of old clothes, consisting of two or three old shirts, a coat or two, a suit of left-off livery, a woman’s gown maybe or a pair of old stays, a couple of pairs of Wellingtons, and waistcoat or so.”

The Blind Bootlace Seller. “At five years old, while my mother was still alive, I caught the small pox. I only wish vaccination had been in vogue then as it is now or I shouldn’t have lost my eyes. I didn’t lose both my eyeballs till about twenty years after that, though my sight was gone for all but the shadow of daylight and bright colours. I could tell the daylight and I could see the light of the moon but never the shape of it. I never could see a star. I got to think that a roving life was a fine pleasant one. I didn’t think the country was half so big and you couldn’t credit the pleasure I got in going about it. I grew pleaseder and pleaseder with the life. You see, I never had no pleasure, and it seemed to me like a whole new world, to be able to get victuals without doing anything. On my way to Romford, I met a blind man who took me in partnership with him, and larnt me my business complete – and that’s just about two or three and twenty year ago.”

The Street Rhubarb & Spice Seller. “I am one native of Mogadore in Morocco. I am an Arab. I left my countree when I was sixteen or eighteen years of age, I forget, sir. Dere everything sheap, not what dey are here in England. Like good many, I was young and foolish – like all dee rest of young people, I like to see foreign countries. The people were Mahomedans in Mogadore, but we were Jews, just like here, you see. In my countree the governemen treat de Jews very badly, take all deir money. I get here, I tink, in 1811 when de tree shilling pieces first come out. I go to de play house, I see never such tings as I see here before I come. When I was a little shild, I hear talk in Mogadore of de people of my country sell de rhubarb in de streets of London, and make plenty money by it. All de rhubarb sellers was Jews. Now dey all gone dead, and dere only four of us now in England. Two of us live in Mary Axe, anoder live in, what dey call dat – Spitalfield, and de oder in Petticoat Lane. De one wat live in Spitalfield is an old man, I dare say going on for seventy, and I am little better than seventy-three.”

The Street-Seller of Walking Sticks. “I’ve sold to all sorts of people, sir. I once had some very pretty sticks, very cheap, only tuppence a piece, and I sold a good many to boys. They bought them, I suppose, to look like men and daren’t carry them home, for once I saw a boy I’d sold a stick to, break it and throw it away just before he knocked at the door of a respectable house one Sunday evening. There’s only one stick man on the streets, as far as I know – and if there was another, I should be sure to know.”

The Street Comb Seller. “I used to mind my mother’s stall. She sold sweet snuff. I never had a father. Mother’s been dead these – well, I don’t know how long but it’s a long time. I’ve lived by myself ever since and kept myself and I have half a room with another young woman who lives by making little boxes. She’s no better off nor me. It’s my bed and the other sticks is her’n. We ‘gree well enough. No, I’ve never heard anything improper from young men. Boys has sometimes said when I’ve been selling sweets, “Don’t look so hard at ’em, or they’ll turn sour.” I never minded such nonsense. I has very few amusements. I goes once or twice a month, or so, to the gallery at the Victoria Theatre, for I live near. It’s beautiful there, O, it’s really grand. I don’t know what they call what’s played because I can’t read the bills. I’m a going to leave the streets. I have an aunt, a laundress, she taught me laundressing and I’m a good ironer. I’m not likely to get married and I don’t want to.”

The Grease-Removing Composition Sellers. “Here you have a composition to remove stains from silks, muslins, bombazeens, cords or tabarets of any kind or colour. It will never injure or fade the finest silk or satin, but restore it to its original colour. For grease on silks, rub the composition on dry, let it remain five minutes, then take a clothes brush and brush it off, and it will be found to have removed the stains. For grease in woollen cloths, spread the composition on the place with a piece of woollen cloth and cold water, when dry rub it off and it will remove the grease or stain. For pitch or tar, use hot water instead of cold, as that prevents the nap coming off the cloth. Here it is. Squares of grease removing composition, never known to fail, only a penny each.”

The Street Seller of Birds’ Nests. “I am a seller of birds’-nesties, snakes, slow-worms, adders, “effets” – lizards is their common name – hedgehogs (for killing black beetles), frogs (for the French – they eats ’em), and snails (for birds) – that’s all I sell in the Summertime. In the Winter, I get all kinds of of wild flowers and roots, primroses, buttercups and daisies, and snowdrops, and “backing” off trees (“backing,” it’s called, because it’s used to put at the back of nosegays, it’s got off yew trees, and is the green yew fern). The birds’ nests I get from a penny to threepence a piece for. I never have young birds, I can never sell ’em, you see the young things generally die of cramp before you can get rid of them. I gets most of my eggs from Witham and Chelmsford in Essex. I know more about them parts than anybody else, being used to go after moss for Mr Butler, of the herb shop in Covent Garden. I go out bird nesting three times a week. I’m away a day and two nights. I start between one or two in the morning and walk all night. Oftentimes, I wouldn’t take ’em if it wasn’t for the want of the victuals, it seems such a pity to disturb ’em after they made their little bits of places. Bats I never take myself – I can’t get over ’em. If I has an order of bats, I buys ’em off boys.”

The Street-Seller of Dogs. “There’s one advantage in my trade, we always has to do with the principals. There’s never a lady would let her favouritist maid choose her dog for her. Many of ’em, I know dotes on a nice spaniel. Yes, and I’ve known gentleman buy dogs for their misses. I might be sent on with them and if it was a two guinea dog or so, I was told never to give a hint of the price to the servant or anybody. I know why. It’s easy for a gentleman that wants to please a lady, and not to lay out any great matter of tin, to say that what had really cost him two guineas, cost him twenty.”

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to take a look at

John Thomson’s Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London

More John Player’s Cries of London

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

Lawrence Jenkin, Spectacle Maker

Algha Works – where Lawrence Jenkin works – is the only historic industrial building still in use in the Fish Island Conservation Area and Britain’s last hand-made spectacle factory, but it is now under threat as the owners have applied for a single-storey extension to convert it to luxury residential use, forcing out the spectacle makers out.

Londoners need workspace and employment as much as they need homes, so I encourage readers to click here and sign this petition to SAVE THE ALGHA WORKS

Lawrence Jenkin by Tom Bunning

Alone in the cavernous basement of the Algha Works in Hackney Wick, I found Lawrence Jenkin hunched over a pair of spectacle frames, entirely absorbed in his work attending to the fine detail of their manufacture. Apart from some modern machinery, it was a sight that evoked Huguenot John Dollond, who was born in Spitalfields in 1705 and created an optical workshop there in Vine St with his son Peter, becoming optician to George III, Lord Nelson and the Duke of Wellington – founding Dollond & Aitchison, the celebrated company of opticians which persisted until recently.

Lawrence has some equally distinguished clients whom discretion prevents us naming and, like John Dollond, his is also a family business in which he has worked with his two brothers, who jointly took over from their father who ran it before them. Yet perhaps we may equally extrapolate backwards from Lawrence’s delight in his work and its methodical processes, to get a glimpse of John Dollond in his workshop in Spitalfields in the eighteenth century?

“My father, Arthur Jenkin, became the breadwinner at only thirteen after his father died, so he got into binoculars and became a businessman. Working as ‘Primatic Instruments,’ he serviced and repaired binoculars for the British & Canadian forces in World War II.

Our family business is the Anglo-American Optical Company, which my father bought in 1946 but which had been going since 1883. Originally, the company was in Southfields near Wimbledon but it was bombed out and when he bought it – as a virtually bankrupt optical business – he moved it to beautiful large old building on the edge of Hampstead Heath.

I am an optician but I always wanted to design and make spectacles. My father said to me, ‘You’re going to have to learn the business and someone else’s expense.’ I qualified in this country and in the United States, where I got the New York and American certificates too. In those days, all opticians sold the same frames but I wanted to create and manufacture my own designs. I was lucky enough to work in an optician on Third Avenue in New York where the owner asked me what I wanted to do and, when I told him, he asked me how much I needed. So I said, ‘Ten thousand pounds’ – that was twenty-four thousand dollars – and he said, ‘Here’s a cheque, go and do it.’

I came back in 1968 and started designing. I was influenced by the National Health Service frames, they had a good basic shape and good designs but they were poorly made. My frames came in more sizes and were made of better materials and components. That’s where I started from.

My father had a factory in Hampstead and he converted the offices into a place to live, so I was fortunate to have a place to manufacture, and my brothers Malcolm and Tony worked with me. I had people making the frames for me in the factory but I was the designer of the collections and I always made the first samples. We called ourselves Anglo American Eyewear.

In 1996, I left and now I just make bespoke frames for clients. It’s a slow process. If I get four pairs done in a week I’m doing well, whereas a commercial frame maker would expect to produce two or three in a day, but I try to make them extremely well. Unlike most other hand made frame makers, I keep a record of each frame and the lenses I have made. If my client wants a replacement or duplicate, it can be re-made accurately from my drawings and records and sent quickly anywhere in the world.

I make glasses for Roger Pope of New Cavendish St who is Optician to the Queen and I have six or seven other clients in Germany, Holland, Japan and United States. Mostly, I make acetate frames but I can make metal frames too although I takes longer, so I have to charge more for it.

Unfortunately, there’s no industry left in this country but there’s a lot of interest from young people in learning how to make frames so I do bit of teaching. It takes a long time to learn. I’m training a couple of people and there’s a huge revival now – it’s such a wonderful thing. So rather than making, I am more interested in passing on my knowledge.

I’ve been in it all my life. My father never forced me or my brothers into the business but we all chose to do it. It’s a nice business. I love it, I love making frames. I wish I was ten years younger because I’d like to make more frames.”

Photographs copyright © Tom Bunning

You may also like to read about