All The Spitalfields Parties Of Yesteryear

The van drivers of the Spitalfields Market certainly knew how to throw a party, as illustrated by this magnificent collection of photographs in the possession of George Bardwell who worked in the market from 1946 until the late seventies. George explained to me how the drivers saved up all year in a Christmas Club and hired Poplar Town Hall to stage shindigs for their families at this season. Everyone got togged up and tables overflowed with sponge cakes and jam tarts, there were presents for all and entertainments galore. Then, once the tables were cleared and the children safely despatched to their beds, it was time for some adult entertainment in the form of drinks and dancing until the early hours.

You may also like to take a look at

At Whitechapel Mission On Christmas Eve

Today I recall a visit to the Whitechapel Mission with my friend the late photographer Colin O’Brien

Before dawn one Christmas Eve, Photographer Colin O’Brien & I ventured out in a rainstorm to visit our friends down at the Whitechapel Mission – established in 1876, which opens every day of the year to offer breakfasts, showers, clothes and access to mail and telephones, for those who are homeless or in need.

Many of those who go there are too scared to sleep rough but walk or ride public transport all night, arriving in Whitechapel at six in the morning when the Mission opens. We found the atmosphere subdued on Christmas Eve on account of the rain and the season. People were weary and shaken up by the traumatic experience of the night, and overcome with relief to be safe in the warm and dry. Feeling the soothing effect of a hot shower and breakfast, they sat immobile and withdrawn. For those shut out from family and social events which are the focus of festivities for the rest of us, and facing the onset of winter temperatures, this is the toughest time of the year.

Unlike most other hostels and day centres, Whitechapel Mission does not shut during Christmas. Tony Miller, who has run the Mission and lived and brought up his family in this building over the last thirty-five years, had summoned his three grown-up children out of bed at five that morning to cover in the kitchen when the day’s volunteers failed to show. Although his staff take a break over Christmas which means he and his wife Sue and their family have to pick up the slack, it is a moment in the year that Tony relishes. “40% of our successful reconnections happen at Christmas,” he explained enthusiastically, passionate to seize the opportunity to get people off the street, “If I can persuade someone to make the Christmas phone call home …”

Tony estimates there are around three thousand people living rough in London, whom he accounts as follows – approximately 15% Eastern Europeans, 15% Africans and 5% from the rest of the world, another 15% are ex-army while 30%, the largest proportion, are people who grew up in care and have never been able to establish a secure life for themselves.

Among those I spoke with on Christmas Eve were those who had homes but were dispossessed in other ways. There were several vulnerable people who lived alone and had no family, and were grateful for a place where they could come for breakfast and speak with others. Here in the Mission, I recognised a collective sense of refuge from the challenges of existence and the rigours of the weather outside, and it engendered a tacit human solidarity. “This is going to be the best Christmas of my life,” Andrew, an energetic skinny guy who I met for the first time that morning, assured me, “because it’s my first one free of drugs.” We shook hands and agreed this was something to celebrate.

Tony took Colin & me upstairs to show us the pile of non-perishable food donations that the Mission had received and explained that on Christmas Day each visitor would be given a gift of a pair of socks, a woollen hat, a scarf and pair of gloves, with a bar of chocolate wrapped inside. Tony told me that on Christmas Day he and his family always have a meal together, but his wife Sue also invites a dozen waifs and strays – so I asked him how he felt about the lack of privacy. “My kids were born here,” he replied with a shrug and a smile and an astonishing generosity of spirit, “after thirty years, I don’t have a problem with it.”

Food donations

Photographs copyright © Estate of Colin O’Brien

Click here to donate to the work of the Whitechapel Mission

You may also like to read about

Last Brew At Syd’s Coffee Stall

Complementing my History of Syd’s Coffee Stall, here is my report on the centenary celebrations

On Friday, I joined the excited throng at Syd’s Coffee Stall on the corner of Calvert Avenue to celebrate the Tothill family’s monumental achievement over three generations, serving tea in Shoreditch for an entire century. Free cups of tea, mince pies and pigs-in-blankets were distributed to all, even cups of Camp Coffee were on offer to the adventurous.

We were grateful for the warm drinks and sustenance as we huddled together under the awning in the pouring rain, reflecting in vertiginous awe upon the notion of a hundred years measured out in tea cups. Sydney Tothill’s grandchildren, Jane & Stephen, presided over the poignant gathering of loyal customers, which included the grandchildren of William Richards, Carriage Builders & Wheelwrights of 280 Hackney Rd, who built the stall for Syd when he started out in 1919.

I chatted to a gentleman who was paying a sentimental visit after sixty-five years. During the fifties, while apprenticed as a furniture maker in Rivington St, he frequented Syd’s stall daily and could not resist returning on this last day to pay his respects and enjoy a final cuppa.

Cheryl Diamond who has worked at the stall since 1995 kept filling the teapot, while Jane Tothill sold raffle tickets and we all contemplated the display of old photographs illustrating the glorious history of Syd’s.

After he was gassed in the trenches of World War I, Syd senior used his compensation money to open the stall. In spite of being a Coffee Stall, Syd only sold tea and beef extract – adopting the description ‘Coffee Stall’ to impart aspiration to his endeavour. When World War II came along, the stall operated twenty-four hours during the London Blitz, serving refreshments to the firemen and auxiliary workers. At the time of the Coronation, Syd junior launched ‘Hillary Caterers’ in honour of Sir Edmund Hillary’s conquest of Everest. As the first and only caterer ever licensed to serve food on the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral, Syd became a Freeman of the City of London.

Yet all good things must come to an end and, when the teapot was drained to the last dregs on Friday, Syd’s Coffee Stall passed into legend as the crowd dispersed into the rain. In January, the old stall will be towed away by the Museum of London where it will remain in perpetuity as a modest wonder, emblematic of the indomitable spirit of Londoners and as enduring testimony to the sustaining properties of an honest cup of tea.

Passionate tea drinkers huddle in the rain

Cheryl Diamond

Stephen, Jane & Geraldine Tothill

Contemplating historic photographs of Syd’s Coffee Stall

You may also like to read about

So Long, Syd’s Coffee Stall

Yesterday, Syd’s Coffee Stall served the last cuppa and closed forever after a century of serving refreshments at the corner of Calvert Avenue and Shoreditch High St. The stall will now be wheeled away to the Museum of London in January where it will reappear as an exhibit when the museum opens at its new home in Smithfield in a few years time.

This is Sydney Edward Tothill pictured in 1920, proprietor of the Coffee Stall that operated for a century, open for business five days a week at the corner of Calvert Avenue and Shoreditch High St, where this photo survived, screwed to the counter of the East End landmark that carried his name. “Ev’rybody knows Syd’s. Git a bus dahn Shoreditch Church and you can’t miss it. Sticks aht like a sixpence in a sweep’s ear,” reported the Evening Telegraph in 1959.

This is a story that began in the trenches of World War I when Syd was gassed. On his return to civilian life in 1919, Syd used his invalidity pension to pay £117 for the construction of a top quality mahogany tea stall with fine etched glass and gleaming brass fittings. And the rest is history, because it was of such sturdy manufacture that it remains in service ninety-nine years later.

Jane Tothill, Syd’s granddaughter who upholds the proud family tradition, told me that Syd’s Coffee Stall was the first to have mains electricity, when in 1922 it was hooked up to the adjoining lamppost. Even though the lamppost in question was supplanted by a modern replacement, it stood beside the stall to provide the power supply. Similarly, as the century progressed, mains water replaced the old churn that once stood at the rear of the stall and mains gas replaced the brazier of coals. In the nineteen sixties, when Calvert Avenue was resurfaced, Syd’s stall could not be moved on account of his mains connections and so kerbstones were placed around it instead. As a consequence, if you looked underneath the stall, the cobbles were still there.

Throughout the nineteenth century, there was a widespread culture of Coffee Stalls in London, but, in spite of the name – which was considered a classy description for a barrow serving refreshments – they mostly sold tea and cocoa, and in Syd’s case “Bovex”, the “poor man’s Bovril.” The most popular snack was Saveloy, a sausage supplied by Wilsons’ the German butchers in Hoxton, as promoted by the widespread exhortation to “A Sav and a Slice at Syd’s.” Even Prince Edward stopped by for a cup of tea from Syd’s while on his frequent nocturnal escapades in the East End.

With his wife May, Syd ran an empire of seven coffee stalls and two cafes in Rivington St and Worship St. The apogee of this early period of the history of Syd’s Coffee Stall arrived when it featured in a silent film Ebb Tide, shot in 1931, starring the glamorous Chili Bouchier and praised for its realistic portrayal of life in East London. The stall was transported to Elstree for the filming, the only time it ever moved from its site. While Chili acted up a storm in the foreground, as a fallen woman in tormented emotion upon the floor, you can just see Syd discharging his cameo as the proprietor of an East End Coffee Stall with impressive authenticity, in the background of the still photograph below.

In spite of Syd’s success, Jane revealed that her grandfather was “a bit of a drinker and gambler” who gambled away both his cafes and all his stalls, except the one at the corner of Calvert Avenue. When Syd junior, Jane’s father was born, finances were rocky, and he recalled moving from a big house in Palmer’s Green to a room over a laundry, the very next week. May carried Syd junior while she was serving at the stall and it was pre-ordained that he would continue the family business, which he joined in 1935.

In World War II, Syd’s Coffee Stall served the ambulance and fire services during the London blitz. Syd and May never closed, they simply ran to take shelter in the vaults of Barclays Bank next door whenever the air raid sounded. When a flying bomb detonated in Calvert Avenue, Syd’s stall might have been destroyed, if a couple of buses had not been parked beside it, fortuitously sheltering the stall from the explosion. In the blast, poor May was injured by shrapnel and Syd suffered a mental breakdown, leaving their young daughter Peggy struggling to keep the stall open.

The resultant crisis at Syd’s Coffee Stall was of such magnitude that the Mayor of Shoreditch and other leading dignitaries appealed to the War Office to have Syd junior brought home from a secret mission he was undertaking for the RAF in the Middle East, in order to run the stall for the ARP wardens. It was a remarkable moment that revealed the essential nature of the service provided by Syd’s Coffee Stall to the war effort on the home front in East London, and I can only admire the Mayor’s clear-sighted sense of priority in using his authority to demand the return of Syd from a secret mission because he was required to serve tea in Shoreditch. As he wrote to May in January 1945, “I do sincerely hope that you are recovering from your injuries and that your son will remain with you for a long time.”

Syd junior was determined to show he was more responsible than his father and, after the war, he bravely expanded the business into catering weddings and events along with this wife Iris, adopting the name “Hillary Caterers” as a patriotic tribute to Sir Edmund Hillary who scaled Everest at the time of the coronation of Elizabeth II. No doubt you will agree that as a caterer for a weddings, “Hillary Caterers” sounds preferable to “Syd’s Coffee Stall.” In fact, Syd junior’s ambition led him to become the youngest ever president of the Hotel & Caterer’s Federation and the only caterer ever to cater on the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral, topping it off by becoming a Freeman of the City of London.

Jane Tothill began working at the stall in 1987 with her brothers Stephen and Edward, and the redoubtable Clarrie who came for a week “to see if she liked it” and stayed thirty -two years. In recent years, Jane managed the stall with the loyal assistance of Francis, who serving behind the counter for the last thirty years. The challenges were parking restrictions that made it problematic for customers to stop, hit and run drivers who frequently caused damage which requiring costly repair to the mahogany structure and graffiti artists whose tags had to be constantly erased from the venerable stall. Yet after a hundred years and three generations of Tothills, during which Syd’s Coffee Stall survived against the odds to serve the working people of Shoreditch without interruption, it became a symbol of the enduring human spirit of the populace here.

Syd’s Coffee Stall is a piece of our social history that does not draw attention to itself, yet deserves to be celebrated. Syd senior might not have survived the trenches in 1919, or he might have gambled away this stall as he did the others, or the bomb might have fallen differently in 1944. Any number of permutations of fate could have prevented the extraordinary survival of Syd’s Coffee Stall for an entire century. Yet by a miracle of fortune, and thanks to the hard work of the Tothill family we enjoyed London’s oldest Coffee Stall here in our neighbourhood for a hundred years. We cherish it now because the story of Syd’s Coffee Stall teaches us that there is a point at which serving a humble cup of tea transcends catering and approaches heroism.

May Tothill, Syd’s wife, behind the counter in the nineteen thirties

Jane Tothill, Syd and May’s granddaughter, behind the counter (photograph by Sarah Ainslie)

Syd junior and his mother May, behind the counter in the nineteen fifties

A still from the silent film “Ebb Tide” starring Chili Bouchier with Syd in a cameo as himself

In 1937 with electricity hooked up to the lamppost

You may also like to read about

Baking Speculaas At E5 Bakehouse

This year Louise Lateur, the Flemish baker at the E5 Bakehouse, has made giant gingerbread figures – or speculaas as they are called in Flanders – in the form of St Nicholas from a nineteenth century mould that has been in her family for generations.

Below you can read my account of the first speculaas Louise baked last year, thereby inaugurating a new Christmas tradition in London.

St Nicholas, newly baked from a nineteenth century mould

Louise Lateur at E5 Bakehouse

Many years ago, I bought a gingerbread figure of St Nicholas in a bakery in Galway. A few years later, I bought another gingerbread figure – this time of Krampus – in Prague. While St Nicholas brings gifts to good children each December, Krampus punishes those who have misbehaved, so I realised that my gingerbread figures belonged together. And all this time, they have lived side by side in a glass case on my bookshelf.

Imagine my excitement when Fiona Atkins, antique dealer and proprietor of Townhouse in Fournier St, showed me a hefty old wooden mould for a gingerbread man she had bought in an auction. The design was of a man in Tudor clothing, not unlike the outfits worn by the yeoman warders at the Tower of London, and the figure was over two and a half feet high. He wore a wide-brimmed hat, a ruff and long quilted coat with slashed sleeves.

At once, I persuaded Fiona to let me find a baker to make us some giant gingerbread men. My good fortune was to meet Louise Lateur, a pastry chef from Flanders working at E5 Bakehouse, who agreed to take on the challenge. Thus it was that, early one frosty morning this week, Contributing Photographer Patricia Niven & I arrived at the Bakehouse under the arches in London Fields to record the baking of London’s largest gingerbread man.

As a Flemish baker, Louise knew that the correct name for these gingerbread figures was ‘speculaas’ and recognised the design of the mould as one of St Nicholas’ helpers. Her father had a similar mould hanging on the wall at home in Ghent and she knew the traditional recipe. “At pastry school in Belgium, it is one of the things you have to make to qualify,” Louise revealed proudly. Yet although Louise has made speculaas, she has never made one of this size before.

Already, Louise had done a week of experimentation to address the challenges posed by the giant gingerbread man. She perfected her recipe to create dough that was flexible enough to take an imprint of all the details of the mould yet stiff enough when baked so the gingerbread man was not too brittle to stand up. At first she experimented with decoration, adding icing to the figure, but decided it was better without. Most importantly, she created the ideal mixture of spices – ginger, cloves, nutmeg, cardamon, pepper and coriander to bake the classic speculaas. “In Belgium,” she revealed, “every bakery has their own spice mix for speculaas.”

Taking out a large lump of the golden dough, Louise rolled it on the table and then placed it on top of the mould, pressing and spreading it out to fill the figure. The density of the dough rendered this an arduous task, demanding twenty minutes of pushing and pummelling, requiring skill and muscle in equal degree. As she worked, Louise trimmed the excess from the back of the mould with a flat knife and added it to the bulk of the dough as it extended to fill the mould.

Once the mould was full and the edges of the dough neatly trimmed, Louise faced the challenge of turning the gingerbread man out in one piece. Tilting the mould sideways, she stood it up on its longest side and then quickly turned it face down onto a sheet of greaseproof paper. Lifting one end carefully, she used her flat knife to coax the edge of the dough from the mould. We held our breaths.

Suddenly the head fell out and, as Louise lifted the mould away, the entire figure rolled down onto the greaseproof paper in a single wave. He did not break and the impression of the mould was perfect in every detail. What had seconds before been mere dough suddenly acquired presence and personality. Behold, London’s largest gingerbread man was born. We stood amazed and delighted at this new wonder of creation.

Exhilarated and relieved, Louise painted the figure with egg white to give it a shine and a crust when baked. Meanwhile the gingerbread man lay inert, regarding us with a vacant grin. After another twenty minutes, he emerged from the oven as shiny-cheeked as a footballer from a tanning salon. Glowing with delight, we stood together and admired our festive bakery miracle. Could this be the birth of a new Christmas tradition in London Fields?

Speculaas are available now at Leila’s Shop and E5 Bakehouse

The Gentle Author’s St Nicholas purchased in Galway in 1989 and Krampus purchased in Prague in 1992

Pressing the dough down into the mould to imprint the design

Slicing off excess dough

The completed mould is filled with gingerbread dough

Preparing to remove the gingerbread man from the mould

The gingerbread man comes out head first

The birth of London’s largest gingerbread man

The gingerbread man and the mould

Detail of the mould

“the gingerbread man lay inert, regarding us with a vacant grin”

Coating the gingerbread man to give him a shine and a crust

Taking him to the oven

The gingerbread man emerges from the oven

London’s largest gingerbread man

Pastry chef Louise Lateur at E5 Bakehouse

Photographs copyright © Patricia Niven

You may also like to read about

Rory Stewart Declares His Support To Save The Whitechapel Bell Foundry

‘An imaginative planner, in fact anyone with any imagination seeing the possibilities here, could not possibly turn this down’ says Rory Stewart

Independent Mayorial Candidate for London, Rory Stewart, came to the East End on a damp wintry day this week to offer his support for our campaign to Save The Whitechapel Bell Foundry as a proper working foundry.

Last week Secretary of State, Robert Jenrick, issued a Holding Order preventing Tower Hamlets Council proceeding with granting permission for change of use to the developers who want to turn the Whitechapel Bell Foundry into a boutique hotel, while he decided what to do.

Now the election is over and Robert Jenrick is back as Secretary of State, we are waiting to hear if he is going to call in the planning application and hold a Public Inquiry. So Rory Stewart’s declaration of support for the campaign this week is opportune timing and we hope this will encourage the Secretary of State to call in the Whitechapel Bell Foundry.

At East London Mosque, Rory Stewart met Steven Musgrave of UK Historic Building Preservation Trust who outlined their plans to reopen the foundry as a proper working foundry and make it viable again, just as they did at Middleport Pottery in Stoke. Then Sufia Alam of the London Muslim Centre spoke on behalf of the mosque and the local community in support of the campaign, explaining Whitechapel Bell Foundry’s immense cultural significance in terms of local pride of place and the opportunity that a renewed foundry offered for apprenticeships, training and education.

Then it was time to head out from the Mosque into the rain where local campaigners had gathered outside the front door of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry to greet Rory Stewart.

Speaking of his enthusiasm for the potential for a renewed bell foundry marrying old and new technology, and with a strong relationship to the local community, he declared, “All of this in one of the most interesting parts of our city – so an imaginative planner, in fact anyone with any imagination seeing the possibilities here, could not possibly turn this down. This is a challenge of courage, it’s a challenge of joyful imagination and of adventure, and we need to let the bells ring forth!”

Rory Stewart in conversation at East London Mosque with Sufia Alam of East London Mosque and Stephen Musgrave of UK Historic Building Preservation Trust

Charles Saumarez Smith welcomes Rory Stewart to the Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Rory Stewart declares his support for our campaign outside the foundry

“This is a challenge of courage, it’s a challenge of joyful imagination and of adventure, and we need to let the bells ring forth!” – Rory Stewart

Rory Stewart at Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Photographs copyright © Andrew Baker

These are three key reasons why the Secretary of State should call in the Whitechapel Bell Foundry and hold a Public Inquiry

You may also like to read about

The Secretary of State steps in

A Letter to the Secretary of State

The Fate of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Nigel Taylor, Tower Bell Manager

Four Hundred Years at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Pearl Binder at Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Dorothy Rendell at Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Hope for The Whitechapel Bell Foundry

A Petition to Save the Bell Foundry

Save the Whitechapel Bell Foundry

So Long, Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Fourteen Short Poems About The Whitechapel Bell Foundry

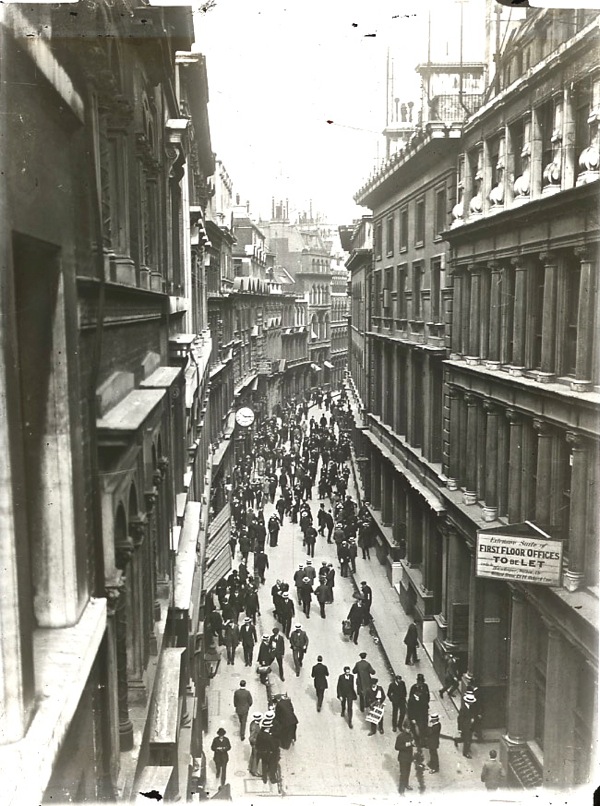

The Streets Of Old London

Piccadilly, c. 1900

In my mind, I live in old London as much as I live in the contemporary London of here and now. Maybe I have spent too much time looking at photographs of old London – such as these glass slides once used for magic lantern shows by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society at the Bishopsgate Institute?

Old London exists to me through photography almost as vividly as if I had actual memory of a century ago. Consequently, when I walk through the streets of London today, I am especially aware of the locations that have changed little over this time. And, in my mind’s eye, these streets of old London are peopled by the inhabitants of the photographs.

Yet I am not haunted by the past, rather it is as if we Londoners in the insubstantial present are the fleeting spirits while – thanks to photography – those people of a century ago occupy these streets of old London eternally. The pictures have frozen their world forever and, walking in these same streets today, my experience can sometimes be akin to that of a visitor exploring the backlot of a film studio long after the actors have gone.

I recall my terror at the incomprehensible nature of London when I first visited the great metropolis from my small city in the provinces. But now I have lived here long enough to have lost that diabolic London I first encountered in which many of the great buildings were black, still coated with soot from the days of coal fires.

Reaching beyond my limited period of residence in the capital, these photographs of the streets of old London reveal a deeper perspective in time, setting my own experience in proportion and allowing me to feel part of the continuum of the ever-changing city.

Ludgate Hill, c. 1920

Holborn Viaduct, c. 1910

Woman selling fish from a barrel, c. 1910

Trinity Almshouses, Mile End Rd, c. 1920

Throgmorton St, c. 1920

Highgate Forge, Highgate High St, 1900

Bangor St, Kensington, c. 1900

Ludgate Hill, c. 1910

Walls Ice Cream Vendor, c. 1920

Ludgate Hill, c. 1910

Strand Yard, Highgate, 1900

Eyre St Hill, Little Italy, c. 1890

Eyre St Hill, Little Italy, c. 1890

Muffin man, c. 1910

Seven Dials, c. 19o0

Fetter Lane, c. 1910

Piccadilly Circus, c. 1900

St Clement Danes, c. 1910

Hoardings in Knightsbridge, c. 1935

Wych St, c.1890

Dustcart, c. 1910

At the foot of the Monument, c. 1900

Pageantmaster Court, Ludgate Hill, c. 1930

Pageantmaster Court, Ludgate Hill, c. 1930

Holborn Circus, 1910

Cheapside, 1890

Cheapside ,1892

Cheapside with St Mary Le Bow, 1910

Regent St, 1900

Glass slides copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at