The Language Of Printing

My portrait of Gary Arber, the legendary East End printer

In celebration of the current exhibition at Nunnery Gallery of the history of printing in the East End, LIGHTBOXES & LETTERING, I have selected favourite entires from John Southward’s ‘Dictionary of Typography’ 1875, chosen as much for their arcane poetry as for the education of my readers.

ABRIDGEMENT – An epitome of a book, made by omitting the less important matter.

ADVERSARIA – Commonplace books: a miscellaneous collection of notes remarks and extracts.

APPRENTICE – An apprentice is a person described in law books as a species of servant, and so called from the French verb apprendre – to learn – because he is bound by indenture to serve a master for a certain term, receiving in return for his services instruction in his masters’s trade, profession or art.

BASTARD TITLE – The short or condensed title preceding full title of the work.

BATTER – Any injury to the face of the type sufficient to prevent it showing clearly in printing.

BEARD OF A LETTER – The outer-angle of the square shoulder of the shank, which reaches almost to the face of the letter, and is commonly scraped off by the Founders, serving to leave a white square between the lower face of the type and the top part of any ascending letter which happen to come in the line following.

BIENVENUE – An obsolete term by which was meant formerly the fee paid on admittance to a ‘Chapel.’

BODKIN – A pointing steel instrument used in correcting, to pick wrong or imperfect letters out of a page.

BOTCHED – Carelessly or badly-done work.

BOTTLE-ARSED – Type that is wider at the bottom than the top.

BOTTLE-NECKED – Type that is thicker at the top than the bottom.

CANDLESTICK – In former times, when Compositors worked at night by the light of candles, they used a candlestick loaded at the base to keep it steady. A few offices use candlesticks at the present day.

CASSIE-PAPER – Imperfect paper, the outside quires of a ream.

CHAFF – Too frequently heard in the printing office, when one Compositor teases another, as regards his work, habits, disposition etc

CHOKED – Type filled up with dirt.

COVENTRY – When a workman does not conform to the rules of the ‘Chapel,’ he is sent to Coventry. That is, on no consideration, is any person allowed to speak with him, apart from business matters, until he pays his dues.

DEAD HORSE – When a Compositor has drawn more money on account than he has actually earned, he is said to be ‘horsing it’ and until he has done enough work in the next week to cover the amount withdrawn, he is said to be working a ‘dead horse.’

DEVIL – is the term applied to the printer’s boy who does the drudgery work of a print office.

DONKEY – Compositors were at one period thus styled by Pressmen in retaliation for being called pigs by them.

EIGHTEENMO – A sheet of paper folded into eighteen leaves, making thirty-six pages.

FAT-FACE LETTER – Letter with a broad face and thick stem.

FLOOR PIE – Type that has been dropped upon the floor during the operations of composition or distribution.

FLY – The man or boy who takes off the sheet from the tympan as the Pressman turns it up.

FORTY-EIGHTMO – A sheet of paper folded into forty-eight leaves or ninety-six pages.

FUDGE – To execute work without the proper materials, or finish it in a bungling or unworkmanlike manner.

GOOD COLOUR – When a sheet is printed neither too dark or too light.

GULL – To tear the point holes in a sheet of paper while printing.

HELL – The place where the broken and battered type goes to.

JERRY – A peculiar noise rendered by Compositors and Pressmen when one of their companions renders themselves ridiculous in any way.

LAYING-ON-BOY – The boy who feeds the sheets into the machine.

LEAN-FACE – A letter of slender proportions, compared with its height.

LIGHT-FACES – Varieties of face in which the lines are unusually thin.

LUG – When the roller adheres closely to the inking table and the type, through its being green and soft, it is said to ‘lug.’

MACKLE – An imperfection in the printed sheets, part of the impression appears double.

MONK – A botch of ink on a printed sheet, arising from insufficient distribution of the ink over the rollers.

MULLER – A sort of pestle, used for spreading ink on the ink table.

NEWS-HOUSE – A printing office in which newspapers only are printed. This term is used to distinguish from book and job houses.

OCTAVO – A sheet of paper folded so as to make eight leaves or sixteen pages.

ON ITS FEET – When a letter stands perfectly upright, it is said to be ‘on its feet.’

PEEL – A wooden instrument shaped like a letter ‘T’ used for hanging up sheets on the poles.

PENNY-A-LINER – A reporter for the Press who is not engaged on the staff, but sends in his matter upon approbation.

PIE – A mass of letters disarranged and in confusion.

PIG – A Pressman was formerly called so by Compositors.

PIGEON HOLES – Unusually wide spaces between words, caused by the carelessness or want of taste of the workman.

PRESS GOES EASY – When the run of the press is light and the pull is easy.

QUIRE – A quire of paper for all usual purposes consists of twenty-four sheets.

RAT-HOUSE – A printing office where the rules of the printers’ trade unions are not conformed to.

SCORPERS – Instruments used by Engravers to clear away the larger portions of wood not drawn upon.

SHEEP’S FOOT – An iron hammer with a claw end, used by Pressmen.

‘SHIP – A colloquial abbreviation of companionship.

SHOE – An old slipper is hung at the end of the frame so that the Compositor, when he comes across a broken or battered letter, may put it there.

SLUG – An American name for what we call a ‘clump.’

SQUABBLE – Lines of matter twisted out of their proper positions with letters running into wrong lines etc.

STIGMATYPY – Printing with points, the arrangement of points of various thicknesses to create a picture.

WAYZGOOSE – An annual festivity celebrated in most large offices.

LIGHTBOXES & LETTERING runs at Nunnery Gallery until Sunday March 29th

You may also like to read about

Along The Regent’s Canal

The Regent’s Canal is two hundred years old this year so I thought I would take advantage of yesterday’s January sunshine to enjoy a ramble along the towpath with my camera, tracing its arc which bounds the northern extent of the East End. At first there was just me, some moorhens, a lonely swan, and a cormorant, but as the morning wore on cyclists and joggers appeared. Starting at Limehouse Basin, I walked west along the canal until I reached the Kingsland Rd. By then clouds had gathered and my hands had turned blue, so I returned home to Spitalfields hoping for another bright day soon when I can resume my journey onward to Paddington Basin.

At Limehouse Basin

Commercial Rd Bridge

Johnson’s Lock

Lock keeper’s cottage at Johnson’s Lock

Great Eastern Railway bridge

Great Eastern Railway bridge

Salmon Lane Lock

Barge dweller mooring his craft

Solebay St Bridge

Mile End Rd bridge

Cyclist at Mile End Rd bridge

Looking through Mile End Rd bridge

Mile End Lock keeper’s cottage

Looking back towards the towers of Canary Wharf

At the junction with Hertford Union Canal

Old Ford Lock

Victoria Park Bridge

Victoria Park Bridge

Looking back from Cat & Mutton Bridge

Barge dwelling cat

At Kingsland Rd Bridge

Looking west from Kingsland Rd Bridge

You may also like to take a look at

Bud Flanagan’s Spitalfields

Bud Flanagan was born above his family’s fish & chip shop in Hanbury St

Today I publish reminiscences of Spitalfields written in 1961 by Bud Flanagan, the celebrated Music Hall comedian, part of the Crazy Gang and half of the legendary Flanagan & Allen double act. Born as Chaim Reeven Weintrop in 1896 into a Polish immigrant family who ran a fried fish shop in Hanbury St, Bud Flanagan began his performing career as a child in East End End Music Hall and came under the spell of street performers beneath the Braithwaite arches in Wheler St – that later featured in the song by which he and Chesney Allen are most remembered today, “Underneath The Arches.”

In common with Charlie Chaplin, who was his close contemporary and performed in Spitalfields at the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties in 1899 where Bud Flanagan became a Call Boy in 1906, he adopted the persona and ragged costume of the dispossessed, revealing pathos and affectionate humour in the lives of those who were seen as downtrodden and marginal.

“The labyrinth of streets that go to make up the district of Spitalfields are narrow and mean. The hub of my world was the churchyard or, as the locals called it, “Itchy Park,” after the doss house habitues who would sun themselves on the benches or low stone walls that surrounded the park. They would sit there every day, scratching, yawning and looking into space. The cemetery was old and derelict, but it was a reminder that at one time Spitalfields was the centre of the weaving trade because nearly all the tombstones bore the inscription, “weaver.” Most of them were dated 1790-1820 and a few were still upright. Several had fallen over and on our way to school we would hop, skip and jump over them.

Hanbury St – where I was born – crawled rather than ran from Commercial St, where Spitalfields Market stood at one end, to Vallance Rd at the other, an artery that spewed itself into Whitechapel Rd at the other. On one corner stood Godfrey Philips’ tobacco factory, with its large ugly enamel signs, black on yellow, advertising “B. D. V. ” – Best Dark Virginia. It took up the whole block until the first turning, a narrow lane with little houses and a small sweet shop.

On the next corner was a barber’s shop and a tobacconist’s which my father owned. Next door to us was a kosher restaurant with wonderful smells of hot salt beef and other spicy dishes, then came the only Jewish blacksmith I ever met. His name was Libovitch, a fine black-bearded man, strong as an ox. From seven in the morning until seven at night, Saturdays excepted, you could hear the sound of hammer on anvil all over the street. Horses from the local brewery, Truman, Hanbury & Buxton, were lined up outside his place waiting to be shod.

Then came another court, all alleys and mean streets. Adjoining was Olivestein, the umbrella man, a fruiterer, a grocer, and then Wilkes St. On one side of it was a row of neat little houses and on the other, the brewery taking up streets and streets, sprawling all over the district. On the corner of Wilkes St stood The Weavers’ Arms, a public house owned by Mrs Sarah Cooney, a great friend of Marie Lloyd. She stood out like a tree in a desert of Jews. Stapletons depository, where horses were bought and sold, was next door to a fried fish shop, number fourteen Hanbury St where I was born. Next to that was Rosenthal, tailors and trimming merchants, then a billiard saloon, after that a money-lenders house where once lived the Burdett-Coutts.

Hanbury St was a patchwork of small shops, pubs, church halls, Salvation Army Hostels, doss houses, pubs, factories and sweat shops where tailors with red-rimmed eyes sewed by the gas-mantlelight. It was typical of the Jewish quarters in the nineties. The houses were clean inside but exteriors were shoddy. The street was narrow and ill-lit. The whole of the East End in those days was sinister.

Neighbours who slaved hard at their businesses left the district (once they began to save money) and moved to what was then nearly the country – Stamford Hill, a suburb in North London that was rapidly becoming a haven for the successful Jewish businessman and artisan. It was only a penny tram ride from Spitalfields to Stamford Hill, but often it took a lifetime of savings and struggle to make the move. When they got there, most were like fish out of water, sad at the parting from old friends and missing the old surroundings. Homesick, they even came all the way back to the East End to do their shopping. Eventually they were joined by their old neighbours, who too had crossed into the Promised Land.

Not everyone was lucky enough to move and among the stay-puts were my parents. First of all, they couldn’t afford it, and secondly the fish shop and barber’s made barely enough to keep a big family of five daughters and five sons. I first saw the light of day, if kids are not like kittens, on 14th October 1896. My parents, who had been in the country for years, could hardly be understood when speaking English. When a child was born the Registrar wrote down a rough phonetic version. I was named Chaim Reeven, which is Hebrew for Reuben and became Robert. My father’s name was Weintrop which the Registrar abruptly changed to “Winthrop.”

Ours was a district where the weak went to the wall and you had to keep your eyes open. When my father opened his fried fish shop, the salt cans were chained to each table and to the counter. But, as in every Jewish home, education was important and apart from ordinary school, I attended cheder for Hebrew lessons three nights a week. The East End at that time had several boys’ and girls’ clubs. I joined the Brady, named after a street tucked behind Hanbury St. We had ping pong, gymnastics and chess and it was a treat to get off the streets into the warm and play games without having fights, of which I had my share.

I became interested in conjuring and used to walk to Gamages in High Holborn and look longingly at the tricks they sold but without the coppers to buy them. To raise the money, I took a job as a Call Boy at the Cambridge Music Hall in Commercial St at the age of ten. The job was very handy. When the pros wanted fish & chips – and they wanted them every night – I went to my father’s shop. There were no wages, only tips, but I was soon able to buy my tricks and those I couldn’t afford I made. When the fish shop was closed on a Sunday, I let the kids in for a farthing, charging the older ones a ha’penny and gave them a show. Mothers would bring their children and soon there was a good sprinkling of grown-ups.

I was making a local name until one Sunday a big rat came out of nowhere and evil-eyed the audience. There were screams and before you could say “Abracadrabra!” the place had emptied. It did not do me any harm but word soon spread, “There are rats in the fish shop,” which was not surprising as we were next to a horse repository with its hay and oats. There wasn’t a morning when the traps had fewer than three or four big ones. I used to watch in fascinated horror as they drowned in a deep tub of water.

That was in 1908, the year the Music Hall artists decided to strike. Being only a call boy, I wasn’t worried by the strikers who picketed the Stage Door trying to persuade the non-strikers to come out. They weren’t really rough, only to the extent if grabbing a bottle of stout or some fish & chips out of my hand and asking whom they were for. I’d tell them and the lot would finish in the gutter. With tears in my eyes, I would run down the long corridor to the Stage Manager at the Prompt Corner and let him know what happened, but mostly I was left alone.

The management who owned the Cambridge also ran the London Music Hall in Shoreditch High St and Collins in Islington. The three halls were known as the L.C.C. – London, Collins & Cambridge. It was at the London that I made my first stage appearance.

Every Saturday at the 2:30pm they had an extra matinee when the acts worked for nothing. The place was packed with a good sprinkling of agents out front to see the fun and maybe pick up an act. The audience were like wolves, all ready for their Roman holiday, booing and jeering at anything they didn’t like. The Stage Manager in the corner, with his hand on the lever, was only too happy to join in the fun and bring down the curtain. The orchestra played with one eye on the music and one eye on the coins or rubbish that would be thrown at some unlucky act on the stage.

I was nearly thirteen and not too bad at manipulating cards and doing other tricks when I went to the London one Saturday afternoon together with my conjuring table and other props. I gave my name as Fargo, the Boy Wizard. The first prize was fifty shillings and a week’s work at the theatre.

The matinee produced some sixteen acts, most old-timers anxious for a week’s job and the cash, together with beginners who had never done a show outside their front room at home. The audience was as rough as ever and, at about 3:30pm, I came on. Being a kid, they were sympathetic towards me, but I was nervous and messed up my first trick. I had to pour water into a tumbler to make it beer and then pour it into another tumbler to make it milk. Alas, in my excitement, I had forgotten to smear the glasses with chemicals and instead of applause came jeers. Foolishly, I then asked to borrow a bowler hat. A bowler in Shoreditch! There was no such thing in the whole of the East End, let alone at the London Music Hall, Shoreditch. Well, I couldn’t do the trick with a cap and had to drop that illusion.

That started them off. Friends were in front, fellow scouts and Brady boys, but I got the bird. The curtain was rung down. I collected my props and and sneaked out of the Stage Door. There stood my father, waiting for me. A stinging right-hander caught me across the face, my ear is twisted, and I heard him saying, “I’ll give you, working on the Sabbath!” I was punched and pushed all the way home. My props lay somewhere in Shoreditch High St. I never saw them again.

I was growing to be a big boy but still working at the Cambridge. On my one free night, Sunday, we would go to the home of a man named Alf Caplin to sing songs and enjoy ourselves. He was a great pianist and one Sunday we decided to form our own quartet. We rehearsed an act and soon landed an engagement at a Dutch Club called “The Netherlands” situated in Bell Lane. The small stage was at the far end of the room and every Sunday there would be five acts, whose pay packet averaged about five shillings each. Dutch clog dancers and yodellers were the favourites. We called ourselves “The Four Hanburys, Juvenile Songsters,” and as there was plenty of club work in London on Sundays, we hoped to be recommended to other clubs.

We opened in harmony and it was nice bright tune, but after about eight bars the harmony was lost and we were all singing the melody but not not in tune. That was the first and only time I have ever been hit by a Dutch herring. I don’t know whether you have seen one but the brine and skin stick to your fingers when you eat them. So you can imagine what it does when one lands on your face. Several more came and that was the Four Hanburys finale.

Competitions were regular feature of the Music Halls and nearly every week the Cambridge had one. A singer, who also ran a competition, was a nice woman named Dora Lyric, married to a successful agent, Walter Bentley. Well, Dora was appearing at the Cambridge and also running the competition. One night there was scarcity of entrants. In desperation, her husband poked me with his stick and said, “Boy, you go on and sing one of Miss Lyric’s songs.” “Who me?” I echoed, trying to hide my eagerness and looking at the Stage Manager who nodded, “Yes.”

Dora Lyric had a popular song, “If you want to be a Somebody,” and I decided to sing that one. Being the only boy in the competition at that house, I won hands down and was picked for the final on Friday night. At the final, there were ten competitors who had won their respective heats, but I won the competition and that precious thirty shillings.

American acts had been coming over to play the Halls for some time now and they fascinated me with their new style and approach to the public and especially by their way of talking. British artists soon cottoned on and before time there was a spate of imitators of American-style acts, watching them from the gallery and then going round the corner to the Arches – a long street under a railway which carried the mainline to Liverpool St Station and ran from Commercial St to Club Row, a Sunday market where they sold mostly dogs and canaries. There the pros would practise to mouth-organ acompaniment, night after night, until they had copied the Yanks most intricate steps.

I became so interested in the Americans that I decided, after talking with them and reading about the States, that I must go there one day. The year was 1910, I was still at school and had about three months to finish. We were still in Hanbury St and on the day before I was fourteen, I made up my mind I was going to the New World, the place my dad tried to get to and never did. But my first impression of New York was a sad shock – Hanbury St, Spitalfields, seemed like the Mall in comparision…”

Chaim Reeven Weintrop (later known as Bud Flanagan) at the age of two with his brother Simon

The red premises are the former fish and chip run by Bud Flanagan’s family, where the young comedian staged magic shows on Sunday afternoons until a rat appeared and put a stop to it. The yard to the right was where Libovitch the blacksmith shoed the horses from the Truman Brewery.

Wolf & Yetta Weintrop fled Poland in the eighteen-eighties hoping to get to New York but settling in Spitalfields where they ran a fish & chip shop in Hanbury St

“On one corner stood Godfrey Phillips’ tobacco factory, with its large ugly enamel signs”

“Stapletons depository, where horses were bought and sold”

Cambridge Theatre of Varieties in Commercial St where Bid Flanagan was a Call Boy at ten years old

Handbill for Cambridge Theatre of Varieties

Bud Flanagan at the peak of his fame

“The Arches – a long street under a railway which carried the mainline to Liverpool St Station and ran from Commercial St to Club Row, a Sunday market where they sold mostly dogs and canaries. There the pros would practise to mouth-organ acompaniment, night after night, until they had copied the Yanks most intricate steps.”

You may also like to read about

Sandle Brothers, Manufacturing Stationers

Not so long ago, there were a multitude of long-established Manufacturing Stationers in and around the City of London. Sandle Brothers opened in one small shop in Paternoster Row on November 1st 1893, yet soon expanded and began acquiring other companies, including Dobbs, Kidd & Co, founded in 1793, until they filled the entire street with their premises – and become heroic stationers, presiding over long-lost temples of envelopes, pens and notepads which you see below, recorded in this brochure from the Bishopsgate Institute.

The Envelope Factory

Stationery Department – Couriers’ Counter

A Corner of the Notepad & Writing Pad Showroom

Gallery for Pens in the Stationers’ Sundries Department

Account Books etc in the Stationers’ Sundries Department

Japanese Department

Picture Postcard & Fancy Jewellery Department

One of the Packing Departments

Leather & Fancy Goods Department

Books & Games Department

Christmas Card, Birthday Card & Calendar Department

A Corner of the Export Department

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

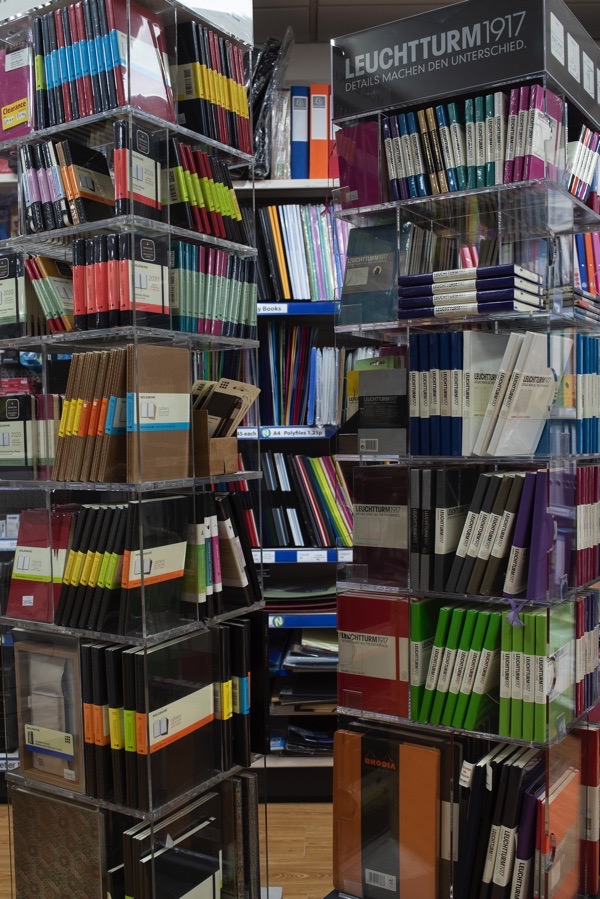

At Newmans Stationery

Qusai & Hafiz Jafferji

Barely a week passes without at least one visit to Newmans Stationery, a magnificent shop in Bethnal Green devoted to pristine displays of more pens, envelopes, folders and notebooks than you ever dreamed of. All writers love stationery and this place is an irresistible destination whenever I need to stock up on paper products. With more than five thousand items in stock, if you – like me – are a connoisseur of writing implements and all the attendant sundries then you can easily lose yourself in here. This is where I come for digital printing, permitting me the pleasure of browsing the aisles while the hi-tech copiers whirr and buzz as they fulfil their appointed tasks.

Swapping the murky January streets for the brightly-lit colourful universe of Newmans Stationers, Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I went along last week to meet the Jafferjis and learn more about their cherished family business – simply as an excuse to spend more time within the hallowed walls of this heartwarming East End institution.

We thought we would never leave when we were shown the mysterious and labyrinthine cellar beneath, which serves as the stock room, crammed with even more stationery than the shop above. Yet proprietor Hafiz Jafferji and his son Qusai managed to tempt us out of it with the offer of a cup of tea in the innermost sanctum, the tiny office at the rear of the shop which serves as the headquarters of their personal empire of paper, pens and printing. Here Hafiz regaled us with his epic story.

“I bought this business in October 1996, prior to that I worked in printing for fifteen years. It was well paid and I was quite happy, but my father and my family had been in business and that was my goal too. I am originally from Tanzania and I was born in Zanzibar where most of my relatives have small businesses selling hardware.

I began my career as a typesetter, working for a cousin of mine in Highgate, then I studied for a year at London College of Printing in Elephant & Castle. My father told me to start up a business running a Post Office in Cambridge in partnership with another cousin. They sold a little bit of stationery so I thought it was a good idea but my mind was always in printing. Every single day, I came back after working behind the counter in Cambridge to work at printing in Highgate, before returning to Cambridge at maybe one or two in the morning. I did that for almost two years, but then I said, ‘I’m not really enjoying this’ and decided to come back to London and work full time with my cousin in Highgate again.

I wondered, ‘Shall I go back to Tanzania where my dad is and start a business there or just carry on here?’ After I paid off my mortgage on my tiny flat, I left the print works and I was doing part time jobs and working a hotel but I thought, ‘Let’s try the army!’ Yet by the time I got to the third interview, I managed to find a job working for a printer in Crouch End. Then I had my mother pushing me to get married. ‘You’ve got a flat and you’ve got a job,’ she said but I could not even afford basic amenities in my house. If I wanted to eat something nice, I had to go to aunt’s house.

I realised I needed a decent job and I joined a printing firm in the Farringdon Rd as a colour planner, joining a team of four planners. Although I had learnt a lot from my previous jobs, I was not one of the most experienced workers there and I found that the others chaps would not teach me because I was the only Asian in the workforce. I used to do my work and watch the others with one eye, so I could pick up what they were doing and get better. I think I was a bit slow and so, for a long time, I would sign out and carry on working after hours to show that I was fulfilling my duties.

We did a lot of printing at short notice for the City and my boss always needed people to stay on and work late. Sometimes he would ring me at midnight and ask. ‘Hafiz, a plate has gone down, can you come in and redo it?’ I always used to do that, I never said ‘No.’

After five years, the boss asked me to become manager but I realised that I wasn’t happy because there were communication difficulties – people would not listen to me. My colleagues did not like the fact that I never said ‘No’ to any job. So I felt uncomfortable and had to refuse the promotion. When I decided to leave they offered me 50% pay rise.

Then a friend of mine who was an accountant told me about Newmans, he said was not doing very well but it was an opportunity. We looked at the figures and it did not make sense financially, compared to what I had been earning, yet me and wife decided to give it a go anyway. It took us seven years to re-establish the business.

I am still in touch with Mr & Mrs Newman who were here in Bethnal Green twelve years before we came along in 1996. Before that, they were in Hackney Rd, trading as ‘Newmans’ Business Machinery’ selling typewriters. I remember when we started there were stacks of typewriter ribbons everywhere! Digital was coming in and typewriters were disappearing so that business was as dead as a Dodo.

It was always in my mind to go into business. My idea was simply that I would be the boss and I would have people working for me taking the money. After working fourteen hours a day for six days a week, I thought it would be easy. Of course, it was not.

We refurbished the shop and increased the range of stock. We had a local actor who played Robin Hood when we re-opened. We wanted an elephant but we had to make do with a horse. We announced that a knight on horseback was coming to our shop.

We deal directly with manufacturers so we can get better discounts and sell at competitive prices. I concentrate on local needs, the demands of people within half a mile of my shop. I go to exhibitions in Frankfurt and Dubai looking for new products and new ideas, I have become so passionate about stationery…”

Nafisa Jafferji

Marlene Harrilal

‘We wanted an elephant but we had to make do with a horse’

The original Mr Newman left his Imperial typewriter behind in 1996

Hafiz Jafferji

Qusai Jafferji quit his job in the City to join the family business

Qusai Jafferji prints a t-shirt in the recesses of the cellar

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Newmans Stationery (Retail, Wholesale & Printing), 324 Bethnal Green Rd, E2 0AG

You may also like to read about

Public Homes On Public Land

Stop the Monster!

Readers may recall that five years ago there was a plan to built a line of towers of luxury investment flats for the international market along the Bishopsgate Goodsyard which would cast the Boundary Estate into permanent shadow. In 2015, the Mayor of London called in the planning application to give it his approval personally but, fortunately, he ran out of time while he was in office and we were saved from this scheme which would have permanently blighted Spitalfields and Shoreditch.

Now that development has reared its ugly head again and, although it is not quite as bad as before, it is still a monster as you can see above.

Taking their inspiration from the Boundary Estate nearby, Weavers Community Action Group are saying that since this is public land it should instead become the location for public homes. If designed by an architect of vision this could become a flagship project, bringing hope to Londoners at the time of the capital’s worst housing crisis.

All are welcome at a public meeting to launch this campaign next Thursday 30th January at 7:30pm at St Hilda’s Community Centre, 18 Club Row, E2 7EY. Below you can read more about the monster development and how to object.

The Boundary Estate was Britain’s first Council Estate

Click on this image to enlarge

You may like to read about the previous proposal

The Bishopsgate Goodsyard Development

A Riverside Walk In the Eighties

David Rees sent me these photographs – published here for the first time today – that he took in the streets within walking distance on either side of the Thames when he worked at Tower Hill in the eighties.

Cathedral St, SE1

“I took these photos when I was working at Trinity House in the early eighties just before the ‘regeneration’ of the London Docks. Crossing the river, it was five minutes’ walk to Shad Thames and ten minutes’ walk to the Liberty of the Clink. Walking east, it was ten minutes via St. Katharine Docks to Wapping where the streets smelt of cinnamon and mace on late summer evenings.” – David Rees

Winchester Sq

Borough Market

Borough Market

Borough Market

Rochester Walk

Nelson’s Wharf from Old Barge House Stairs

Anchor Brewery

Clink St

Mill St

Hays Wharf

Weston St

Church of the English Martyrs seen from Chamber St

Longfellow Rd Mission

Essex Wharf

Holland St

Wapping Old Stairs

Queen Elizabeth St

Billingsgate Market

Chambers Wharf

Crown Wharf

Green Dragon St

Free Trade Wharf

Oliver’s Wharf

Oxo Tower

St Benet’s Wharf

Photographs copyright © David Rees

You may also like to take a look at