The Pellicci Museum

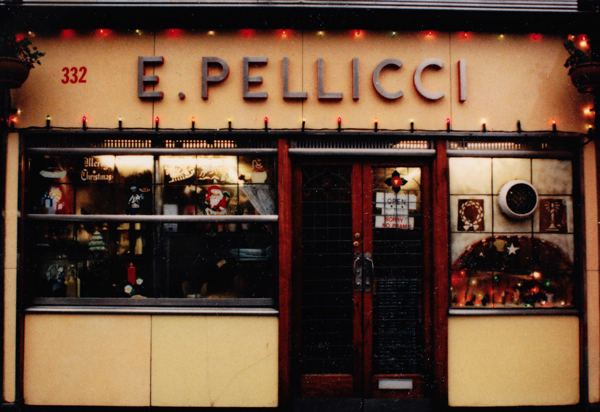

This is Lucinda Rogers‘ drawing of E.Pellicci in the Bethnal Green Rd, London’s most celebrated family-run cafe, into the third generation now and in business for over a century – and continuing to welcome East Enders who have been coming for generations to sit in the cosy marquetry-lined interior and enjoy the honest, keenly-priced meals prepared every day from fresh ingredients.

E.Pellicci is a marvel. It is so beautiful it is listed, the food is always exemplary and I every time I come here I leave heartened to have met someone new.

I found Lucinda Rogers’ drawing on the wall in one of the small upper rooms that now serves as an informal museum of the history of the cafe, curated by Maria Pellicci’s nephew – Toni, a bright-eyed Neapolitan, who has been working here since he left school in Lucca in Tuscany and came to London in 1970. He led me up the narrow staircase, opened the door of the low-ceilinged room and with a single shy gesture of his arm indicated the family museum. Toni has lined the walls with press cuttings, photographs and all kinds of memorabilia, which tell the story of the ascendancy of Pellicci’s, attended by a few statues of saints to give the pleasing aura of a shrine to this cherished collection.

Primo Pellici began working in the cafe in 1900 and it was here in these two rooms that his wife Elide brought up his seven children single-handedly, whilst running the cafe below to keep the family after her husband’s death in 1931. Elide is the E.Pellicci whose initial is still emblazoned in chrome upon the primrose-hued vitroglass fascia and her portrait remains, she and her husband counterbalance each other eternally on either side of the serving hatch in the cafe. In 1921, Nevio senior was born in the front room here. He ran the cafe until his death in 2008, superceded as head of the family business today by his wife Maria who possesses a natural authority and charisma that makes her a worthy successor to Elide.

As I sat alone in the quiet of the room, leafing through the albums, surrounded by the walls of press coverage, Maria came upstairs from the kitchen to join me. She pointed out the flat roof at the rear where her former husband Nevio played as a child. “He was very happy here,” she assured me with a tender smile, standing silently and casting her eyes between the two empty rooms – sensing the emotional presence of the crowded family life that once filled in this space that is now a modest store room and an office. Maria and Nevio brought up their children in a terraced house around the corner in Derbyshire St, and these days Toni goes round each morning early to pick her up from there, before they start work around six at the cafe she runs with her son Nevio and daughter Anna.

Pellicci’s collection tells a very particular history of the twentieth century and beyond – of immigration, of wars, of coronations and gangsters too. But, more than this, it is a history of wonderful meals, a history of very hard work, a history of great family pride, and a history of happiness and love.

Primo Pellicci still presides upon the cafe where he started work in 1900.

Primo’s children, Nevio and Mary Pellicci, 1930.

Pellicci’s wartime licence issued to Elide Pellicci in 1939 by the Ministry of Food.

Pellicci’s paper bag issued to celebrate the Coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953 – note the phone number, Bishopsgate 1542.

Mary and Maria Pellicci, Trafalgar Sq, 1963.

Nevio junior, aged seven, skylarking outside the house in Derbyshire St with pals Claudio and Alfie.

Nevio senior and Toni, 1980.

Pellicci’s customers in 1980.

Nevio senior, 1980.

Nevio and Toni.

Christmas card from Charlie Kray, 1980.

Nevio junior and Nevio senior.

George Flay’s portrait of Nevio Junior, 2006. See more at www.artofflay.com

George Flay’s montage of the world of Pellicci’s.

Nevio Senior, 2005

You may also enjoy reading

The Executions Of Old London

In the days before the internet, television or cinema, public executions were a popular source of entertainment in London. Ed Maggs, fourth generation proprietor of Maggs Bros booksellers (now safely esconced in their new home at 48 Bedford Sq), sent me this fine selection of Execution Broadsides that he came across recently.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution Broadside of Henry Horler for the murder of his wife Ann Horler on 17th November 1852, at Sun St, Bishopsgate.

Ann Horler’s mother, Ann Rogers, came to take her daughter away from her husband Henry Horler on the night before the murder was discovered. She had been told that her daughter had been abused by her husband. Henry Horler insisted his wife would not go with her mother that night, but Mrs Rogers should return in the morning for her. The next morning Ann Horler was found dead.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of John Wiggins at Newgate, 15th October 1867, for the murder of Agnes Oakes on the morning of Wednesday 24th July at Limehouse. Printed with the trial and execution of Louis Bordier, a Frenchman charged with the murder of Mary Ann Snow on the 3rd September 1867 on Old Kent Rd.

Agnes Oakes lived with John Wiggins as his wife for about six months prior to the murder. Neighbours said they witnessed John beating Agnes and she had said she would leave him if he did not stop.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of Michael Barrett, the Fenian, and last man to be hanged in public, on the 26th May 1868, Newgate. Barrett was arrested for the “Clerkenwell Explosion” on 13th December 1867 which killed twelve people and injured many others. Barrett was the only Irish Republican to be convicted of the crime, five others were acquitted.

This tragic event occurred during an attempt to release Richard O’Sullivan Burke from prison. The explosion was misjudged and not only did it blast a sixty foot hole in the prison wall, (O’Sullivan Burke is thought to have been killed in the blast), a number of tenements on Corporation Lane were also destroyed.

The conviction appeared largely to be based on the fact Michael Barrett was a Fenian and that several witnesses claimed he may have been in London at the time. Barrett stated he was in Glasgow on the day of the explosion and if ‘there were 10,000 armed Fenians in London, it was ridiculous to suppose they would send to Glasgow for a person of no higher abilities than himself.’

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of John Devine for the murder of Joseph Duck in the early morning of 11th March 1863, Little Chesterfield St, Marylebone.

The condemned pleaded not guilty to the crime which appeared to result from a robbery that went wrong. The jury was sympathetic to Devine and, although the verdict returned was guilty, there was a strong recommendation to mercy, as they were of the ‘opinion that the prisoner inflicted the injuries on the deceased while in the act of robbing him; but, at the same time they thought he did not intend to murder him.’ The scene of the execution was described thus: ’There was not a large concourse assembled to witness the sad spectacle, nor was there exhibited by those present any of that unseemly demonstrativeness which they are wont to indulge in.’

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of the nurse Catherine Wilson for the murder by poisoning with colchicine of her patient Maria Soames in Albert St, Bloomsbury, on the 18th October 1856. The last woman to be publicly hanged in London.

This was Catherine Wilson’s second indictment for poisoning a patient, having been acquitted the first time round to the astonishment of many. When the first trial took place, on 16th June 1862, in the documents the accused appeared as Constance Wilson and was also occasionally found under the alias Catherine Taylor/Turner. Immediately, she was taken back in to custody and charged with the murder of Maria Soames. During the initial trial, the police had been busy putting together evidence of further victims and even exhumed several bodies, including that of Ann Atkinson, Peter Mawer and James Dixon, who was one of Ms. Wilson’s former lovers. In seven of these exhumed bodies a variety of poisons were found.

The Judge presiding said he had ’never heard of a case in which it was more clearly proved that murder had been committed, and where the excruciating pain and agony of the victim were watched with so much deliberation by the murderer.”

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of Dr William Palmer, for the poisoning of John Parsons Cook at Stafford. Dr Palmer was described by Charles Dickens as ‘The greatest villain that ever stood at the Old Bailey’ in his article on ’The Demeanor of Murderers’. He is also referenced in several novels and an Alfred Hitchcock film.

He was also suspected, although never indicted, of the murder of his four children, all of whom died in infancy, his wife Ann Palmer, Brother Walter Palmer, a house guest Leonard Bladen, and his mother-in-law, Ann Mary Thornton. The doctor benefited financially from all of these deaths.

Dr Palmer was executed at Stafford Prison Saturday 14th June 1856. Although not mentioned in this broadside, the prisoner was said to have had an interesting exchange with the prison governor moments before his death. When Dr Palmer was asked to confess his crimes, the exchange went thus:

Dr Palmer – ’Cook did not die from strychnine.’

Prison Governor -’There is not time for quibbling – Did you or did you not kill Cook?’

Dr Palmer – ’The Lord Chief Justice summed up for poisoning by strychnine.’

In the trial text, it is stated Dr Palmer reiterated he was: ‘innocent of poisoning Cook by strychnia.’

The Judge stated in his summation: ‘Whether it is the first and only offence of this sort which you have committed is certainly known only to God and your own conscience.’

Dr Palmer became notorious for his supposed crimes. It was said 20,000 people attended his execution and a wax figure of him was displayed at Madame Tussauds in the Chamber of Horrors from 1857 – 1979.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Trial broadside of Thomas Cooper,‘would-be’ highwayman, for the murder of Timothy Daly, policeman, and also for shooting at and maiming, with intent to murder, Charles Mott (a baker), and Charles Moss (another police officer) on 5th May at Highbury.

The defence, Mr Hory, addressed the jury, saying ‘for the first time during the seven years that he had been at the bar, he was called upon to address a jury upon a charge, conviction upon which was certain death. He almost felt that his anxiety would defeat itself. He could not help referring to different published statements, most of them monstrous perversions of established fact, and all calculated to excite the prejudices of a jury. When he saw these he could hardly fancy they lived in an enlightened age’.

Mr Hory made the case that the prisoner was not of sound mind, citing attempts of suicide, and claims of being Dick Turpin and Richard III. But this defence was unsuccessful with the jury reached a verdict of guilty, and Thomas Cooper was sentenced to death and executed July 7th 1842.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of Charles Peace the notorious Blackheath burglar, for the murder of Arthur Dyson at Banner Cross, on the 29th November 1876.

Charles Peace murdered Arthur Dyson after become obsessed with Mr Dyson’s wife. Then Peace went on the run for two years with a £100 reward on his head, until he was betrayed by his mistress, Mrs Sue Thompson, who revealed his whereabouts to the police. She never received her expected reward as the police claimed her information did not lead directly to Peace’s arrest. He was caught on 10th October 1878, by Constable Robinson, who Peace shot at five times.

Subsequently, a waxwork figure of Charles Peace featured at Madame Tussaud’s, and two films and several books were produced about his life and crimes.

Images courtesy of Maggs Bros

You may also like to read about

Pamela Cilia, Truman’s Bottling Girl

The Battle for Brick Lane exhibition curated by The Gentle Author at Annetta Pedretti’s House, 25 Princelet St, E1 6QH, is open from noon until 6pm this Saturday 12th & Sunday 13th June, and every weekend through July. If you would like to volunteer to invigilate, please email heloise@spitalfieldstrust.com

There will be a protest march to Stop The Truman Brewery Shopping Mall this Sunday, meeting in Altab Ali Park at 11:45am for speeches followed by a procession up Brick Lane with banners and music. Please come to show your support.

Pamela Cilia

The reputation of the Truman’s bottling girls has passed into legend in Spitalfields. In the course of my interviews so many people have regaled me with tales of this heroic tribe of independent spirited females. who wore dungarees and clogs which thundered upon the cobbles as made their way through the narrow streets en masse, that I have been seeking one of these glamorous and elusive creatures for years.

Consequently, I was more than happy to make a trip to Rainham to pay a call upon Pamela Cilia, who proved to be a fine specimen of a bottling girl, full of vitality, sharp intelligence and strong opinions to this day. Illuminated by sparkling charisma and filling with joyous emotion as she recounted her story, Pamela was no disappointment.

“I loved it, I loved it, really loved it. But when my husband discovered I was going to work at Truman’s, he said, ‘I don’t want you working in that *******.’ He called it a certain place. Yet he already worked there, so I said to him, ‘If you give the place such a bad name, why are you working there?’ My first job was at Charrington’s in Mile End Rd until that closed down, then I worked for Watney Mann’s for seven years in Sidney St before they sold it to Truman’s, and that’s how we all ended up in Truman’s.

In the bottling plant, you had the filler, then you had the discharger and the labelling. The boxes came down and we filled them up. If a vacancy appeared on a machine, they did it by seniority – I think there were about seven machines. They had one ‘Galloping Major’ that done pints and quarts, and all the others were little bottles. They also had the canning machine. I was mainly on the canning machine.

We never had all this ‘safety,’ like now. We never wore glasses, we never had earpieces, so it was really dangerous, especially when the bottles went ‘bang’– especially when you had one in your hand and it exploded. You’d be getting them out of the pasteuriser, then all of a sudden ‘bang, bang bang, bang!’ because they hit against one another and they were hot from the pasteuriser.

I was forty-four and my children were all at school. In those days we lived in two rooms. Two pound a week, that’s what we paid. And my friend Doris used to take the kids to school and she used to bring them home. I clocked in at half past seven and finished at five.

When we got paid on Thursday’s, we used to go over to the Clifton – Thursday was curry day. My friend Adele said ‘I’ll take you to an Indian restaurant.’ At first, she took me to a restaurant near Middlesex Street, near the old toilets. ‘I’ll take you there for a curry,’ she offered, so I said ‘All right’ but when we ate there, I told her, ‘Oh, I don’t like that, Adele.’ The food was too hot.

The following Thursday we went to the Clifton, and on the tables were peppers. Terry, the engineer – big bloke – he said ‘Pam …’ He was going out with Adele and had a row with her, they weren’t talking. He said, ‘Pam, it’s no good asking her for a roll …’ So I offered, ‘All right, I’ll get one for you.’ He said, ‘I want cheese and tomato.’ I got him two cheese and tomato rolls, but I took a pepper and took the pips out and put them in with the tomato pips. Then I gave them to him and went home afterwards, because I knew what he would do. I was a bit of a joker. I didn’t worry about anything. Nobody got me down.

My sister was different. She was a worrier. I mean, I went there one day and she was crying her eyeballs out. And they all said to me. ‘Pam, Betty’s crying,’ and I said, ‘What are you crying for?’ So she told me that Yvonne, or whatever her name was, said, ‘We can’t go home in her car if we smoke.’ I said ‘Listen, you don’t need her car. You got a pair of legs. Walk on them. Or get a cab home. Don’t let them get you down.’ Well, all the girls in there, they said ‘Pam, how brave you are, you don’t care.’

I met my partner at Truman’s. He was a student of nineteen and I was forty-eight, they used to take students on at Truman’s at busy times. One day, I was out with Adele and she said,‘Pam, I’m not coming to dinner with you today’ and I went ‘You’re not? Why’s that?’ She said to me ‘A student has asked me to have a drink with him at dinner time.’ I replied, ‘Oh, I see, we’ll see about that’. I went straight over to Bernie and asked, ‘Excuse me, can I speak to you?’ And he said ‘Yes’ and I said ‘Are you taking my friend, Adele, for a drink at dinnertime?’ He said, ‘Yes’ and I said, ‘I don’t think so.’ He said, ‘What?’ and I said again ‘I don’t think so.’ He said, ‘Why’s that?’ and I said, ‘If you take her then you’ve got to take me too.’ He went, ‘Oh, alright then, you can come too,’ and I said, ‘Never mind about alright, I’m coming…’

Later, Adele met a student too. Bernie was only nineteen when I met him and I’ve been with him for thirty-eight years. I’ve got four children from my first marriage. My youngest one is sixty-one now. I got one at sixty-one, one at sixty-two, one at sixty-three and the eldest one’s three years older, she’s sixty-six. So I’ve not done bad, bringing up four kids in two rooms. I may be eighty-three but I’m still as lively as if I was twenty-one.

I was brought up in Malta because my father was Maltese. We used to come back and forth, he was a seaman. In the end, he gave up the sea because he had malaria and he was in Addenbrooke’s hospital in Cambridge, where they told him that he could get better treatment in London – so we all moved back to where my mother came from.

There were a lot of Maltese people in the East End then, but they had a very bad name. My husband was Maltese. He was a good husband but he used to hate me talking to bad girls and I’d ask him, ‘Why?’ In Stepney, you’d see the prostitutes, you had them all living in them houses next the hospital where they had furnished rooms. If they saw you with your kids, you don’t say to your child, ‘Don’t talk to her, she’s no good, she’s a so-and-so.’ That’s not me. For me, she’s a human being. Her life is her life. What happened was he said ‘Look Pam, say there’s a crowd of Maltese in Whitechapel’ – which there used to be years ago, they all gathered near the station. He said, ‘You’re not gonna talk to them. I’m being straightforward with you.’ He didn’t want me to get categorised like that or be labelled.

He didn’t want me to work at the bottling plant either, but I done it anyway. See, I’m stubborn. You had every creed, every race. I mean I’m gonna be fair because I have to, I got to swear. When I went in in the morning, I’d say ‘Good Morning, Sweary Mary,’ and she’d say to me ‘F*** off, you Maltese bastard!’

‘You Irish, you Welsh, you Scotch, you Black, you White’ – she’d have a name for every one of one of them. We had Lil, we used to call her ‘Barley-Wine Lil’ because, as soon as she came in, she’d grab a plastic cup. We’d all be thinking she was drinking tea – but she wasn’t! This was seven o’clock in the morning and she was drinking barley wine!

It was very, very good experience for me. I mean, if anything happens to me, I’ve had a good life. I loved the atmosphere, the fighting, and the swearing. And to me, they were straightforward people. Because they’d row with you today and speak to you tomorrow. They didn’t hold it against you. See, I’m a type of person can’t hold rows with people, I just want to be friends, you know.

Once, Me & Adele went down Brick Lane to the market and Sweary Mary was in front of us. We were in our welly boots and our overalls. They had these big stalls down Wentworth Street on a Friday or a Thursday, and we saw Mary – well I tell you what, I’ve never run from nobody. I said to Adele, ‘Look, Sweary Mary’s in front.’ Adele shouts out ‘Sweary Mary!’ Oh, she just turned round and shouted at us ‘F*** off, you Truman’s whores.’ Oh, did we laugh. I mean, it’s not nice really, but that was us. We couldn’t do it today. When you got home you were a different person because you were in your family.

If someone phoned me up and said ‘Pam, there is a permanent vacancy at Truman’s, would you do it?’ The answer’d be, ‘Yes.’ I’d probably go with one leg. You had your ups and downs but there was no violence and – the beer! It was nobody’s business.

Terry, the bloke I gave the peppers to, he was a comedian. It was so hot in the bottling plant that all we had on was our cross-over aprons and our bras and pants. I had a high chair, and I had to grab these cans and pull them forward. One day, he came behind my chair and – this is all because of the pepper in the cheese and tomato roll – I knew he’d get me back, but he didn’t get me straight away. He took my chair and tipped it upside down over a container for old cardboard boxes. He shook me, picking me up and throwing me off my chair into the big container. I couldn’t get out, my friends had to pass me wooden boxes so I could make steps to get out. Well you know, it was dangerous.

Yes, we had a bad name. Like I told you, my husband didn’t want me to go there because of the bad name. But it doesn’t mean to say you’re all the same. Yes, I had a laugh and joke, I’m not saying I didn’t. As I said, that bloke Terry got hold of me, he turned me upside down, my boobs went over my shoulders, and I didn’t think nothing of it. But my husband – to this day – he never knew. I didn’t see harm in it. But no, it was good, I loved it. Honest, I loved it. If it hadn’t closed down, I would still be there. I would probably be the sweeper-up!

My husband died after I left Truman’s but I had already met Bernie, and the marriage was already on the rocks. I left him in the end. I always said, ‘Once my children grow up, I’m off.’ And when my children got married, the last one, I was off. And that is how I met Bernie.

At first, they all thought that he was a policeman and I knew that thieving was going on, pinching beer. So he came in one morning and he had navy trousers on, and Adele said to me, ‘Pam, there’s a policeman in here.’ So I said, ‘What do you mean, a policeman?’ I went to him ‘Oi, are you a policeman?’ and he said, ‘No.’ Of course, when we saw him in the morning, we used to shout, ‘Morning, Officer!’ But it’s true, his father was a police sergeant at Chequers and he grew up there. We always said he was a bit of a snob.

I’m eighty-three and Bernie’ll be fifty-eight this year. We just hit it off, age didn’t make any difference. We clicked from that day we met. And he is good as gold. It was fate. I say to myself, ‘It’s fate you meeting Bernie, he wanted a bottling girl.’ He’s been in a lot of places, Bernie. He met Harold Wilson and – who’s that other prime minister? But that’s another story…”

Pamela Cilia at home in Rainham – ” I’m eighty-three and still as lively as if I was twenty-one.”

Labels courtesy Stephen Killick

Transcript by Jennifer Winkler

You may also like to read these other Truman’s stories

First Brew at the New Truman’s Brewery

Lyndie Wright, Puppeteer

As a child, I was spellbound by the magic of puppets and it is an enchantment that has never lost its allure, so I was entranced to visit The Little Angel Theatre in Islington. All these years, I knew it was there – sequestered in a hidden square beyond the Green and best approached through a narrow alley overgrown with creepers like a secret cave.

Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I were welcomed by Lyndie Wright who co-founded the theatre in 1961 with her husband John in the shell of an abandoned Temperance Chapel. “We bought the theatre for seven hundred and fifty pounds,” she admitted cheerfully, letting us in through the side door,“but we didn’t realise we had bought the workshop and cottage as well.”

More than half a century later, Lyndie still lives in the tiny cottage and we discovered her carving a marionette in the beautiful old workshop. “People travel for hours to get to work, but I just have to walk across the yard,” she exclaimed over her shoulder, absorbed in concentration upon the mysterious process of conjuring a puppet into life. “Carving a marionette is like making a sculpture,” she explained as she worked upon the leg of an indeterminate figure, “each piece has to be a sculpture in its own right and then it all adds up to a bigger sculpture.” In spite of its lack of features, the figure already possessed a presence of its own and as Lyndie turned and fondled it, scrutinising every part like puzzled doctor with a silent patient, there was a curious interaction taking place, as if she were waiting for it to speak.

“I made puppets as a child,” she revealed by way of explanation, when she noticed me observing her fascination. Growing up and going to art school in South Africa, Lyndie applied for a job with John Wright who was already an established puppet master, only to be disappointed that nothing was available. “But then I got a telegram,” she added, “and it was off on an eight month tour including Zimbabwe.”

After the tour, Lyndie came to Britain continue her studies at Central School of Art and John was seeking a location to create a puppet theatre in London. “The chapel had no roof on it and we had to approach the Temperance Society to buy it,” Lyndie recalled, “We did everything ourselves at the beginning, even laying the floorboards and scraping the walls.” Constructed upon a corner of a disused graveyard, they discovered human remains while excavating the chapel to create raked seating as part of the transformation into a theatre with a fly tower and bridge for operating the marionettes. Today, the dignified old frontage stands proudly and the auditorium retains a sense of a sacred space, with attentive children in rows replacing the holy teetotallers of a former age.

“I had intended to return to South Africa, but I had fallen in love with John so there was no going back,” Lyndie confided fondly, “in those days, we sold the tickets, worked the puppets, performed the shows, and then rushed round and made the coffee in the interval – there were just five of us.” At first it was called The Little Angel Marionette Theatre, emphasising the string puppets which were the focus of the repertoire but, as the medium has evolved and performers are now commonly visible to the audience, it became simply The Little Angel Theatre. Yet Lyndie retains a special affection for the marionettes, as the oldest, most-mysterious form of puppetry in which the operators are hidden and a certain magic prevails, lending itself naturally to the telling of stories from mythology and fairytales.

John Wright died in 1991 but the group of five that started with him in Islington in 1961 were collectively responsible for the growth and development in the art of puppetry that has flourished in this country in recent decades, centred upon The Little Angel Theatre. Generations of puppeteers started here and return constantly bringing new ideas, and generations of children who first discovered the wonder of the puppet theatre at The Little Angel come back to share it with their own children.

“The less you show the audience, the more they have to imagine and the more they get out of it,” Lyndie said to me, as we stood together upon the bridge where the puppeteers control the marionettes, high in the fly tower. The theatre was dark and the stage was empty and the flies were hung with scenery ready to descend and the puppets were waiting to spring into life. It was an exciting world of infinite imaginative possibility and I could understand how you might happily spend your life in thrall to it, as Lyndie has done.

Old cue scripts, still up in the flies from productions long ago

Larry, the theatrical cat

Lyndie Wright

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Visit The Little Angel Theatre website for details of current productions

The Lavender Fields Of Surrey

I cannot imagine a more relaxing way to enjoy a sunny English summer afternoon than a walk through a field of lavender. Observe the subtle tones of blue, extending like a mist to the horizon and rippling like the surface of the sea as the wind passes over. Inhale the pungent fragrance carried on the breeze. Delight in the orange butterflies dancing over the plants. Spot the pheasants scuttling away and – if you are as lucky as I was – encounter a red fox stalking the game birds through the forest of lavender. What an astonishing colour contrast his glossy russet pelt made as he disappeared into the haze of blue and green plants.

Lavender has been grown on the Surrey Downs for centuries and sold in summer upon the streets of the capital by itinerant traders. The aromatic properties and medicinal applications of lavender have always been appreciated, with each year’s new crop signalling the arrival of summer in London.

The lavender growing tradition in Surrey is kept alive by Mayfield Lavender in Banstead where visitors may stroll through fields of different varieties and then enjoy lavender ice cream or a cream tea with a lavender scone afterwards, before returning home laden with lavender pillows, soap, honey and oil.

Let me confess, I had given up on lavender – it had become the smell most redolent of sanitary cleaning products. But now I have learnt to distinguish between the different varieties and found a preference for a delicately-fragranced English lavender by the name of Folgate, I have rediscovered it again. My entire house is scented with it and the soporific qualities are evident. At the end of that sunny afternoon, when I returned from my excursion to the lavender fields of Surrey, I sat down in my armchair and did not awake again until supper time.

‘Six bunches a penny, sweet lavender!’ is the cry that invites in the street the purchasers of this cheap and pleasant perfume. A considerable quantity of the shrub is sold to the middling-classes of the inhabitants, who are fond of placing lavender among their linen – the scent of which conquers that of the soap used in washing. – William Craig Marshall’s Itinerant Traders, 1804

‘Delight in the orange butterflies dancing over the plants…’

Thomas Rowlandson’s Characteristic Series of the Lower Orders, 1820

‘Six Bunches a-Penny, Sweet Lavender – Six Bunches a-Penny, Sweet Blooming Lavender’ from Luke Clennell’s London Melodies, 1812

‘Spot the pheasants scuttling away…’

From Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

Card issued with Grenadier Cigarettes in 1902

WWI veteran selling lavender bags by Julius Mendes Price, 1919

Yardley issued Old English Lavender talcum powder tins from 1913 incorporating Francis Wheatley’s flower seller of 1792

Archive images courtesy © Bishopsgate Institute

Mayfield Lavender Farm, 1 Carshalton Rd, Banstead SM7 3JA

You may also like to read about

Misericords At St Katharine’s Precinct

Tutivillus the demon eavesdropping upon two women

I spent a morning on my knees in St Katharine’s Chapel in Limehouse, photographing these rare survivors of fourteenth century sculpture, believed to have been created around 1360 for the medieval St Katharine’s Chapel next to the Tower of London, which was displaced and then demolished for the building of the docks in 1825.

These marvellous carvings evoke a different world and another sensibility, combining the sacred and profane in grotesque and fantastical images that speak across time as emotive and intimate expressions of the human imagination. I am particularly fascinated by the sense of mutability between the human and animal kingdom in these sculptures, manifesting a vision of a mythic universe of infinite strange possibility which was once familiar to our forebears.

Intriguingly, these misericords appear to have been created by the same makers who carved those at Lincoln and Chester cathedrals, and a friary in Coventry.

After a sojourn of over a hundred years in Regent’s Park, the Royal Foundation of St Katharine, originally founded by Queen Matilda in 1147, moved back to the East End to Limehouse in 1948 where it flourishes today, offering an enclave of peace and reflection, sequestered from the traffic roaring along the Highway on one side and Commercial Rd on the other.

Centaur with club and shield

Tutivillus holds the parchment on the Day of Judgement

Owl

Bust of a bearded man in a striped cap with a cape and trailing drapery

Winged beast with a long tail and human head

Dragon

Edward III

Queen Philippa

Bishop’s head

Green man

Bearded man wearing a cap

A former Master of St Katharine’s was Chancellor of the Exchequer

Angel playing the bagpipes

Pelican in her piety with three chicks, supported by a pair of swans

Lion leaping upon the amphisbaena, supported by reptilian monsters

Coiled serpentine monster

Woman riding a beast with a man’s head

Elephant and castle surmounted by a crowned head

Beast with a hooded human head

Miser

Choir stalls with misericords

St Katharine’s Chapel was built in 1951 on the site of St James, Ratcliffe, destroyed in the blitz

Late fifteenth or early sixteen century carving of angel musicians playing a psaltery, a harp and tabor

The Royal Foundation of St Katharine, 2 Butcher Row, Limehouse, E14 8DS

With thanks to the Master of the Royal Foundation of St Katharine for permission to photograph the misericords

If you are interested to visit St Katharine’s Chapel please write to info@rfsk.org.uk

George Parrin, Ice Cream Seller

Please keep your eyes open for my old friend George Parrin, the Ice Cream Seller, who is cycling around the East End now and, if you see George, stop him and buy one – and he will tell you his story.

‘I’ve been on a bike since I was two’

I first encountered Ice Cream Seller, George Parrin, coming through Whitechapel Market on his bicycle. Even before I met him, his cry of ‘Lovely ice cream, home made ice cream – stop me and buy one!’ announced his imminent arrival and then I saw his red and white umbrella bobbing through the crowd towards us. George told me that Whitechapel is the best place to sell ice cream in the East End and, observing the looks of delight spreading through the crowd, I witnessed the immediate evidence of this.

Such was the demand on that hot summer afternoon that George had to cycle off to get more supplies, so it was not possible for me to do an interview. Instead, we agreed to meet next day outside the Beigel Bakery on Brick Lane where trade was a little quieter. On arrival, George popped into the bakery and asked if they would like some ice cream and, once he had delivered a cup of vanilla ice, he emerged triumphant with a cup of tea and a salt beef beigel. ‘Fair exchange is no robbery!’ he declared with a hungry grin as he took a bite into his lunch.

“I first came down here with my dad when I was eight years old. He was a strongman and a fighter, known as ‘Kid Parry.’ Twice, he fought Bombardier Billy Wells, the man who struck the gong for Rank Films. Once he beat him and once he was beaten, but then he beat two others who beat Billy, so indirectly my father beat him.

In those days you needed to be an actor or entertainer if you were in the markets. My dad would tip a sack of sand in the floor and pour liquid carbolic soap all over it. Then he got a piece of rotten meat with flies all over it and dragged it through the sand. The flies would fly away and then he sold the sand by the bag as a fly repellent.

I was born in Hampstead, one of thirteen children. My mum worked all her life to keep us going. She was a market trader, selling all kinds of stuff, and she collected scrap metal, rags, woollens and women’s clothes in an old pram and sold it wholesale. My dad was to and fro with my mum, but he used to come and pick me up sometimes, and I worked with him. When I was nine, just before my dad died, we moved down to Queens Rd, Peckham.

I’ve been on a bike since I was two, and at three years old I had my own three-wheeler. I’ve always been on a bike. On my fifteenth birthday, I left school and started work. At first, I had a job for a couple of months delivering meat around Wandsworth by bicycle for Brushweilers the Butcher, but then I worked for Charles, Greengrocers of Belgravia delivering around Chelsea, and I delivered fruit and vegetables to the Beatles and Mick Jagger.

At sixteen years old, I started selling hot chestnuts outside Earls Court with Tony Calefano, known as ‘Tony Chestnuts.’ I lived in Wandsworth then, so I used to cycle over the river each day. I worked for him for four years and then I made my own chestnut can. In the summer, Tony used to sell ice cream and he was the one that got me into it.

I do enjoy it but it’s hard work. A ten litre tub of ice cream weighs 40lbs and I might carry eight tubs in hot weather plus the weight of the freezer and two batteries. I had thirteen ice cream barrows up the West End but it got so difficult with the police. They were having a purge, so they upset all my barrows and spoilt the ice cream. After that, Margaret Thatcher changed the law and street traders are now the responsibility of the council. The police here in Brick Lane are as sweet as a nut to me.

I bought a pair of crocodiles in the Club Row animal market once. They’re docile as long as you keep them in the water but when they’re out of it they feel vulnerable and they’re dangerous. I can’t remember what I did with mine when they got large. I sell watches sometimes. If anybody wants a watch, I can go and get it for them. In winter, I make jewellery with shells from the beach in Spain, matching earrings with ‘Hello’ and ‘Hola’ carved into them. I’m thinking of opening a pie and mash shop in Spain.

I am happy to give out ice creams to people who haven’t got any money and I only charge pensioners a pound. Whitechapel is best for me. I find the Asian people are very generous when it comes to spending money on their children, so I make a good living off them. They love me and I love them.”

Photographs copyright © Estate of Colin O’Brien

You might also like to read about

Matyas Selmeczi, Silhouette Artist