The Lantern Slides Of Old London

Hundreds of lantern slides from the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society Collection are published in THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S LONDON ALBUM, making it the ideal present for lovers of London’s history.

A few years ago, I became enraptured by a hundred-year-old collection of four thousand lantern slides. They were once used for educational lectures by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society at the Bishopsgate Institute in Spitalfields. When Stefan Dickers became archivist there, he discovered the slides in dusty old boxes – abandoned and forgotten since they became obselete. Yet it has become apparent that these slides, which were ignored for so long, are one of the greatest treasures in the collection. And it is my delight to be the one responsible for publishing a selection of these wonderful images in my London Album.

When I was first offered the opportunity of presenting these lantern slides which have been unseen for generations, I was overwhelmed by the number of pictures and did not know where to start. The first to catch my fancy were the ancient signs and symbols, dating from an era before street numbering located addresses and lettered signs advertised trades to Londoners.

Before long, I grew spellbound by the slide collection because, alongside the famous landmarks and grand occasions of state, there were pictures of forgotten corners and of ordinary people going about their business. It was a delight to discover hundreds of images of things that people do not usually photograph and I was charmed to realise that the anonymous photographers of the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society were as interested in pubs as they were in churches.

The more I studied the glass slides, the more joy I found in these arcane pictures, since every one contained the rich potential of hidden stories, seducing the imagination to flights of fancy regarding the ever-interesting subject of Old London. Once I had published The Signs of Old London, I realised there were many other such sets to be found among the slides, as a result of the systematic recording of London which underscored the original project by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society, a hundred years ago, and parallels my own work in Spitalfields Life, today.

I arranged them quite literally – in terms of doors, or night, or dinners, or streets, or staircases. I did this because I was interested to explore how the pictures might speak to me and to you, the readers. No evidence has survived to indicate in what sequence or order they were originally shown and it was my intention to avoid imposing any grand narratives of power or poverty, although these pictures do speak powerfully of these subjects. Recognising that objects and images are capable of many interpretations, I am one that prefers museums which permit the viewer to decide for themselves, rather than be presented with artefacts subject to a single meaning within an ordained story and so, with the Album, we have presented the pictures and invited the reader to draw their own conclusions.

Equally, in publishing the slides, we chose not to clean them up or remove imperfections and dirt. Similarly, we did not standardise the colour to black or a uniform sepia, either. Instead, we have cherished the subtle variations of hues present in these slides and savoured the beautiful colour contrasts between them, when laid side by side. There is a melancholic poetry in these shabby images, in which their damage and their imperfections speak of their history, and I came to glory in the patina and murk.

Above all, in publishing these pictures in my Album, I wanted to communicate the pleasure I have found in scrutinising them at length and entering another world imaginatively through the medium of this sublime photography. Today I publish this serendipitous selection of glass slides which fascinate me but that did not make it into my Album.

In the Inns of Court

At Eltham Palace

At Euston Station

The Anchor at Bankside

Crocodiles at the Natural History Museum

Reading Room at the British Museum

Chelsea Pensioner

In Fleet St

In Fleet St

St John’s Gate, Clerkenwell

Between the inner & outer dome of St Paul’s

Along the Embankment

The Old Dick Whittington, Clothfair, Smithfield

Firemen take a tea break

Lightermen on the Thames

Flood in Water St, Tower of London

The White Tower, London’s oldest building

Glass slides courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute

Take a look at these sets of the glass slides of Old London

The High Days & Holidays of Old London

The Fogs & Smogs of Old London

The Forgotten Corners of Old London

The Statues & Effigies of Old London

The City Churches of Old London

Chapter 2. Horrid Murder

I am looking forward to welcoming readers to the BLOOMSBURY JAMBOREE this weekend, 11th & 12th December at Art Workers Guild, 6 Queens Sq, WC1N 3AT. My readings are sold out, but I shall be on hand each day and delighted to sign and inscribe books.

The River Thames Police Office occupies the same site today on the Thames beside Wapping New Stairs as it did in 1811. Once news of the murders on the Ratcliffe Highway reached here in the early hours of December 8th, Police Officer Charles Horton who was on duty at the time, ran up Old Gravel Lane (now Wapping Lane) and forced his way through the crowd that had gathered outside the draper’s shop. He searched the house systematically and, apart from the mysterious chisel on the counter, he found five pounds in Timothy Marr’s pocket, small change in the till and £152 in cash in a drawer in the bedroom – confirming this was no simple robbery.

In the bedroom, he also found the murder weapon, a maul or heavy iron mallet such as a ship’s carpenter would use. It was covered in wet blood with human hair sticking to it. At least two distinct pairs of footprints were discerned at the rear door, containing traces of blood and sawdust – the carpenters had been at work in the shop that day. A neighbour confirmed a rumbling in the house as “about ten or twelve men” were heard to rush out.

Primary responsibility for fighting crime in the parish of St George’s-in-the-East lay with the churchwardens who advertised a £50 reward for information, including the origin of the maul. The Metropolitan Police was only established in 1829 – in 1811 there was no police force at all as we would understand it and, as news of the mystery spread through newspaper reports, a disquiet grew so that people no longer felt the government was capable of keeping then safe in their own homes. Indicative of government concern at the national implications of the case, the Home Secretary offered a reward of £100.

Meanwhile a constant stream of sightseers passed through the Marr’s house, viewing the bodies laid out on their beds, and some left coins in a dish because Mr Marr had only left sufficient capital for his creditors to be paid nineteen shillings in the pound. The bill for the renovation of the shop was yet to settled.

Three days after the crime, on 10th December 1811, when the inquest was held at the Jolly Sailor public house just across the Highway from Marr’s shop, a vast crowd gathered outside rendering the wide Ratcliffe Highway impassable. Walter Salter, the surgeon who had examined the bodies, Margaret Jewell the servant, John Murray the neighbour and George Olney the watchman all told their stories. The jury gave a verdict of wilful murder.

For two centuries the Ratcliffe Highway had an evil reputation. Wapping was the place of execution for pirates, hanged on the Thames riverbank at low water mark until three tides had flowed over them. Slums spread across the marshy ground between the Highway and the Thames, creating the twisted street plan of Wapping that exists today. This unsavoury neighbourhood grew up around the docks to service the needs of sailors and relieve them as completely as possible of their returning pay. Now it seemed that these murders had confirmed everyone’s prejudices, superstitions and fears of the Highway – sometimes referred to as the Devil’s Highway.

Whoever was responsible for these terrible crimes was still abroad walking the streets.

Expect further reports over coming days as new developments in this case occur.

River Police Headquarters, Wapping New Stairs

Click on Paul Bommer’s map of the Ratcliffe Highway Murders to explore further

I am indebted to PD James’ ‘The Peartree & The Maul’ which stands as the authoritative account of these events. Thanks are also due to the Bishopsgate Institute and Tower Hamlets Local History Archive.

You may like to read the first instalment of this serial which runs throughout December

Matyas Selmeczi, Silhouette Artist

Have your silhouette cut by Matyas Selmeczi at the BLOOMSBURY JAMBOREE this weekend, 11th & 12th December at Art Workers Guild, 6 Queens Sq, WC1N 3AT.

With his weathered features, grizzled beard, sea captain’s cap and denim bib overalls, Silhouette Artist Matyas Selmeczi looks like he has just stepped off a boat and out of another century.

Such is his gentle, unassuming personality that it is possible you may not have noticed Matyas sitting in his booth in Spitalfields, yet I urge you to seek him out because this man is possessed of a talent that verges on the magical. With intense concentration, he can slice through a piece of paper with a pair of scissors to produce a lifelike portrait in silhouette in less than three minutes, and he does this all day.

Once his subject sits in front of him looking straight ahead, Matyas takes a single considered glance at the profile and then begins to cut a line through the paper, looking up just a couple of times without pausing in his work, until – hey presto! – a likeness is produced. The medium is seemingly so simple and the effect so evocative.

Silhouettes were invented in France in the eighteenth century and named after Etienne de Silhouette, a finance minister who was a notorious cheapskate. These inexpensive portraits became commonplace across Europe until they were surpassed by the age of photography and when you meet Matyas, you know that he is the latest in a long line of silhouette artists on the streets of London through the centuries.

In spite of photography, silhouettes retain their currency today as vehicles to capture and convey human personality in ways that are distinctive in their own right. And for less than a tenner, getting your silhouette done is both a souvenir to cherish and an unforgettable piece of theatre.

“I have always been able to draw and I trained as an architect in St Petersburg. When my daughter was eight years old, I tried to teach her to draw but it was too early and she would cry. A pair of scissors were on the table so I picked them up and cut her silhouette to make her smile – that was my very first. When she was twelve, I was able to teach my daughter to draw and now she has become an architect.

In 2009, I was working in Budapest as an architect, but there was a crash in Hungary so I came to London. I found there was also a crash here, so I couldn’t get a job and I decided to do silhouettes instead. The first two years were hard but interesting. I did not know anything, I started in Trafalgar Sq. A friendly policeman explained that I could not charge, instead I had to ask for donations.

Then I was on the South Bank for two years and I used to have a line of people waiting to have their silhouettes done. In winter it was very hard, I had gloves and put my hands in my pockets to keep them warm so I was ready to work, but it was very windy and the wind blew away my easel and folding chair.

So I came to Brick Lane where I can charge money but I have to pay rent, and I’ve been here every weekend since, and I am in Camden from Wednesday to Friday. On Monday and Tuesday, I am free to do my own drawing and painting.

To draw a portrait you start from the brow and draw the profile but with a silhouette you begin with the neck. It is like a drawing but you only make one line and you cannot make any mistake in the middle. It is like a shadow or a ghost. It takes me three minutes but it is not hard for me.

I like to do father and son, mother and daughter and it is very interesting to see the similarities and the differences, and how the profile changes over time.

Anybody can take photographs but silhouettes require skill. It is not really an art but a beautiful craft. You must have good eyes and very good hands.

The first time I saw a silhouette being cut was in Milos Forman’s ‘Ragtime.’ In the first few minutes of the film, you are in the Jewish quarter of New York and you see a silhouette artist on the street.

Once on the South Bank, I had a very old lady at the end of the queue watching me and I thought she had no money, so I offered to cut her silhouette for free – but she said, ‘No, I am a silhouette artist.’

She had come to this country as a child with her family from Vienna in the thirties escaping Hitler and cut silhouettes on the streets of London. Her name was Inge Ravilson and she was eighty-eight years old. She invited me to her home, and I visited her and we drank tea.

We became friends. She was wonderful and she taught me her tricks. She could cut a silhouette very fast, in one minute, and she told me I am too slow but my work is more characterful, so I was very proud. I know I am not the best, but she told me I am good and she gave me her scissors. That’s good enough for me.”

Photographs copyright © Estate of Colin O’Brien

Matyas Selmeczi is available for parties, weddings and events.

You may also like to read about

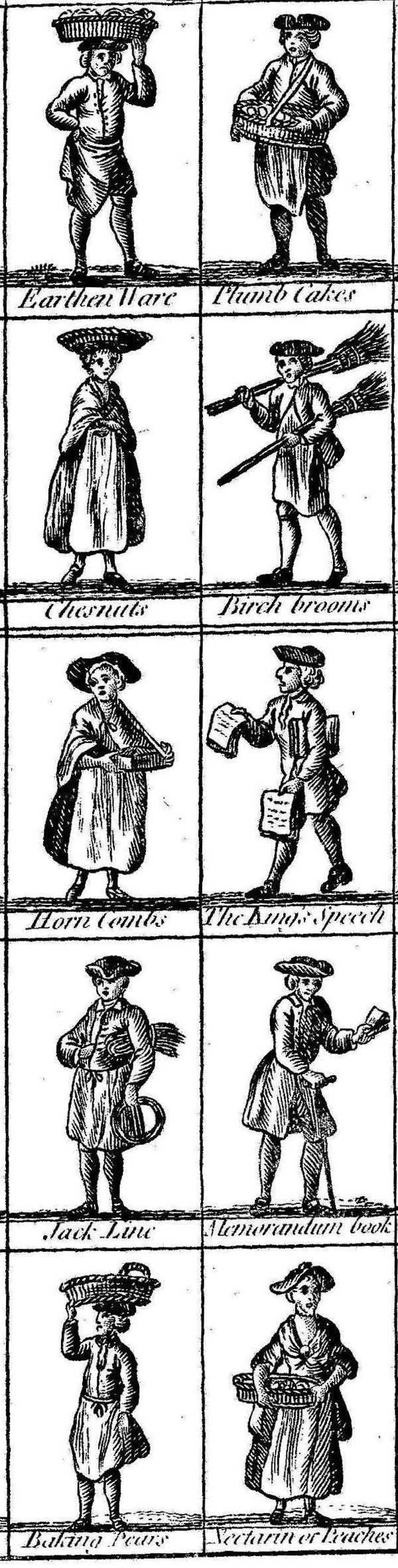

Matilda Moreton & The Cries Of London

When I met ceramicist Matilda Moreton, I knew that she was one after my own heart in her love for THE CRIES OF LONDON. So I am delighted that Matilda will be presenting her work at the BLOOMSBURY JAMBOREE this weekend, 11th & 12th December at Art Workers Guild, 6 Queens Sq, WC1N 3AT.

We still need volunteers over the weekend – if you can help please email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com

Cries of London mugs by Matilda Moreton

‘I have a passion for Bowles & Carver’s eighteenth century street cries and they are my favourite of all those I discovered while researching my ceramics degree project at Central St Martin’s nearly twenty years ago. The richness of London’s history always inspired me through the challenges of living as a country mouse in town. The Thames is an extraordinary archaeological resource and I became a mudlark in more ways than one, both getting my hands dirty along the foreshore and gardening in London clay.

I make quite different work now I live in Somerset, where I set up a studio in an old log shed with clay roof tiles. It has companionable scurrying in the rafters, cows out at the back and chickens coming in to clear up the spiders. Here I have returned to the whirling mud pit that is throwing on the wheel, but sometimes I use my old potshards from the Thames, impressing textures from long-gone Bellarmine jugs and the like.

The Bloomsbury Jamboree is the ideal opportunity for me to revisit my work inspired by the history of London, add in my mud-larking, introduce my new work from Somerset and tie things together.’

Matilda Moreton

Click here to buy a copy for £20

Chapter 1. The Death Of A Linen Draper

Late on 7th December 1811, on the site where this former car dealership now stands, Timothy Marr, a twenty-four-year-old linen draper was closing up his business at 29 Ratcliffe Highway, a stone’s throw from St George’s-in-the-East.

In the basement kitchen, his wife Celia was feeding their baby, Timothy junior. At ten to midnight on the last night of his life, the draper sent out his servant girl, Margaret Jewell, with a pound note and asked her to pay the baker’s bill and buy oysters for a late supper.

Timothy Marr made his fortune through employment in the East India Company and had his last voyage aboard the Dover Castle in 1808 when he was twenty-one. With the proceeds, he married and set up shop just one block from the London Dock wall. Already Mr Marr’s business was prospering and in recently he had employed a carpenter, Mr Pugh, to modernise the premises. The facade had been taken down, replaced with a larger shop window and the work had been completed smoothly, apart from the loss of a chisel.

When Margaret Jewell walked down the Highway she found Taylor’s oyster shop shut. Retracing her steps along the Ratcliffe Highway towards John’s Hill to pay the baker’s bill, she passed the draper’s shop again at around midnight where, although Mr Marr now had put up the shutters with the help of James Gowen, the shop boy, she could see Mr Marr at work behind the counter.

“The baker’s shop was shut,” Margaret later told the coroner, so she went elsewhere in search of oysters and, finding nowhere open, returned to the draper’s about twenty minutes later to discover it dark and the door locked. She jangled the bell without answer until – to her relief – she heard a soft tread inside on the stair and the baby cried out.

But no-one answered the door. Panic-stricken and fearful of passing drunks, Margaret waited a long half hour for the next appearance of George Olney, the watchman, at one o’clock. Mr Olney had seen Mr Marr putting up the shutters at midnight but later noticed they were not fastened and when he called out to alert Mr Marr, a voice he did not recognise replied, “We know of it.”

John Murray, the pawnbroker who lived next door, was awoken at quarter past one by Mr Olney knocking upon Mr Marr’s door. He reported mysterious noises from his neighbour’s house shortly after midnight, as if a chair were being pushed back and accompanied by the cry of a boy or a woman.

Mr Murray told the watchman to keep ringing the bell while he went round the back through the yard to the rear door, which he found open with a faint light visible from a candle on the first floor. He climbed the stairs in darkness and took the candle in hand. Finding himself at the bedroom door, he said, “Mr Marr, your window shutters are not fastened” but receiving no answer, he made his way downstairs to the shop.

It was then he discovered the first body in the darkness. James Gowen was lying dead on the floor just inside the door with his skull shattered with such violence that the contents were splattered upon the walls and ceiling. In horror, the pawnbroker stumbled towards the entrance in the dark and came upon the dead body of Mrs Marr lying face down in a pool of blood, her head also broken. Mr Murray struggled to get the door open and cried in alarm, “Murder! Murder! Come and see what murder is here!” Margaret Jewell screamed. The body of Mr Marr was soon discovered too, behind the counter also face down, and someone called out,“The child, where’s the child?” In the basement, they found the baby with its throat slit.

When more light was brought in, the carpenter’s lost chisel was found upon the shop counter but it was perfectly clean.

Later this week and over the coming Christmas season, you may expect more reports from me upon the Ratcliffe Highway Murders as further incidents take place…

Timothy Marr’s shop

Click on Paul Bommer’s map of the Ratcliffe Highway Murders to explore further

I am indebted to PD James’ ‘The Peartree & The Maul’ which stands as the authoritative account of these events. Thanks are also due to the Bishopsgate Institute and Tower Hamlets Local History Archive.

Maria Pellicci’s Christmas Ravioli

Elide Pellicci looks down upon Maria & Nevio Pellicci

If you should spot a light, gleaming after hours in the back kitchen at E. Pellicci in the Bethnal Green Rd at this time of year, it will be Maria Pellicci making the Christmas ravioli for her family as she has done each year since 1962.

Maria originates from the same tiny village of Casciana near Lucca in Tuscany as her late husband Nevio Pellicci (senior). And, to her surprise, when Maria first arrived in London she discovered his mother Elide Pellicci, who came over in 1899, was already making ravioli to the same recipe that she knew from home in Italy.

Elide is the E. Pellicci celebrated in chrome letters upon the primrose yellow art deco facade of London’s best-loved family-run cafe, the woman who took over the running of the cafe in the thirties after the death of her husband Priamo who worked there from 1900 – which means we may be assured that the Christmas ravioli have been made here by the Pelliccis in this same spot for over a century.

Thus it was a great honour that Contributing Photographer Patricia Niven & I were the very first outsiders to be invited to witness and record this time-hallowed ritual in Bethnal Green. But I regret to inform you that this particular ravioli is only ever made for the family, which means the only way you can get to taste it is if you marry into the Pelliccis.

“It’s a Tuscan Christmas tradition – Ravioli in Brodo – we only do it once a year and every family has their own recipe,” Maria admitted to me as she turned the handle of the machine and her son Nevio Pellici (junior) reached out to manage the rapidly emerging yellow ribbon of pasta. “My mother and my grandmother used to make it, and I’ve been doing it all my life.”

In recent years, Maria has been quietly tutoring Nevio in this distinctive culinary art that is integral to the Pellicci family. “I was going with the boys to see Naples play against Arsenal tonight, but that’s down the drain,” he declared with good grace – revealing he had only discovered earlier in the day that his mother had decided the time was right for making the special ravioli, ready for the whole family to eat in chicken broth on Christmas Day.

“He’s a good boy,” Maria declared with a tender smile, acknowledging his sacrifice, “years ago I used to stay here on my own making the ravioli until eleven o’clock at night.”

“She’s trying to hand it over to me,” Nevio confirmed proudly.

“Nevio’s good and he’s got the patience,” Maria added encouragingly, as Nevio lowered the pasta carefully onto the ravioli mould.

“I’ve got the rubbish job, I have to fill the ravioli,” he complained in mock self-pity, grinning with pleasure as the two of them set to work with nimble fingers to fill the ravioli. Although the precise ingredients are a fiercely guarded secret, Maria confided to me that the filling comprises beef and pork with Parmigiano and Percorino, along with other undisclosed seasonings. “Everyone does it differently,” she confessed modestly, making light of the lifetime of refining that lies behind her personal recipe.

Already Maria had cooked the mixture slowly for a hour and added a couple of eggs to bind it, and – now it had cooled – she and Nevio were transferring it into the ravioli mould. “We used to do this by hand,” she informed me, turning contemplative as she watched Nevio expertly produce another ribbon of yellow pasta to sit on top of the mould. “We rolled the pasta out on the table before we had the machine. Sometimes, large families used to fill the whole table rolling out enough pasta to feed everyone on Christmas Day. When my mother was small, they were poor and lived in a hut but they had their own flour and eggs, so they could always make pasta.”

It was Nevio’s task to turn the mould over and press it down hard onto the table, binding the layers of pasta together. Then, with intense concentration as Maria waited expectantly, he peeled the ravioli away from the mould, revealing a sheet that looked like a page of neatly upholstered postage stamps. Making swift work of it, Maria wielded her little metal wheel by its wooden handle, separating the individual ravioli and transferring them to a metal tray.

In the kitchen of the empty restaurant, mother and son surveyed their fine handiwork with satisfaction. Each mould produced forty ravioli and, in the course of the evening, they made eight batches of ravioli, thus producing three hundred and sixty ravioli to delight the gathered Pelliccis on Christmas Day – and thereby continuing a family tradition that extends over a century. Yet for Maria, Ravioli in Brodo is more than a memento of her origin in Tuscany, making it here in the East End over all this time incarnates this place as her home.

“I am happy here and I know everyone in Bethnal Green,” she admitted to me, “It’s my village and it’s my family.”

Maria & Nevio rolling out the pasta

Maria sprinkles semolina in the mould to stop the pasta sticking

Maria & Nevio placing the meat filling in the ravioli

Nevio presses down on the ravioli mould

The ravioli are turned out from the mould

Maria cuts out the individual ravioli

Over three hundred ravioli ready for Christmas Day

Elide & Priamo, the Pellicci ancestors look down in approval upon the observance of making Christmas ravioli for more than a century in Bethnal Green

Photographs copyright © Patricia Niven

E.Pellicci, 332 Bethnal Green Rd, E2 0AG

You may like to read my other Pellicci stories

Maria Pellicci, The Meatball Queen of Bethnal Green

Colin O’Brien’s Pellicci Portraits ( Part One)

Colin O’Brien’s Pellicci Portraits (Part Two)

George Cruikshank’s Festive Season

As we brace ourselves for the forthcoming festive season, let us contemplate George Cruikshank‘s illustrations of yuletide in London 1838-53 from his Comic Almanack which remind us how much has changed and also how little has changed. (You can click on any of these images to enlarge)

A swallow at Christmas

Christmas Eve

Christmas Eve

Christmas dining

Christmas bustle

Boxing day

Hard frost

A picture in the gallery

Theatrical dinner

The Parlour & the Cellar

New Year’s Eve

New Year’s birth

Twelfth Night – Drawing characters

January – Last year’s bills

You may also enjoy

George Cruikshank’s Comic Alphabet