Women Of Bethnal Green At Work

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

Merle Curtis, Sultana Begum, Armagan Middlemast & Husna Begum, Tower Hamlets Food Bank

Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie‘s exhibition opens tomorrow November 10th and runs until March 31st 2023 at Oxford House, Bethnal Green

“Women of Bethnal Green at Work has emerged from a collaboration with some of the amazing women in the area and celebrates the rich variety of the work they do. The generosity of these women who welcomed me into their working lives to photograph them is a testament to their indomitable spirit. Searching and finding women to take part has been an adventure and I am grateful to all those who helped by passing on names and ideas. I have encountered a range of work across launderettes, the Underground, café kitchens, care homes, food banks, the fire service, funeral directors, the Post Office, freelance electricians, artists, seamstresses and many more unsung women who sustain and bind together the special community of Bethnal Green with their warmth, labour and friendship”.

Sarah Ainslie

Afa Simpson, Painter, Decorator & Clown

Donna Wood, Postwoman, Royal Mail

Claire Carmelo, Customer Service Assistant, Bethnal Green Station

Kelly Wood, Carer, Silk Court Care Home

Kellyan Saunders, Manager, Oxfam Shop

Lucinda Rogers, Artist

Maria & Anna Pellicci, E Pellicci

Nafisa & Marlene, Newmans’ Stationery

Rachel Hippolyte, Education Manager, Spitalfields City Farm

Anita Patel, Tesco

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Lew Lessen, Barber

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

It is my pleasure to publish this interview and series of photographs, comprising a portrait of Lew Lessen who opened his barber’s shop in Shacklewell Lane in 1932, undertaken by Neil Martinson more than forty years ago. “He was a gentle and modest man who was proud of his trade,” Neil admitted to me.

Neil is currently selling prints from his photography exhibition at Two More Years until next Saturday 13th November to raise money for Hackney Food Bank. Click here to find out more

“The craft of barbering is a most honourable profession – even royalty take their hats off to us. I was apprenticed to a barber. My Dad signed an agreement for me to learn the trade for two years at a shop in Southampton St, which is now Conway St. The hours were long. We were open from 8am to 8pm every day with one hour for lunch, and we opened until 9pm on Saturdays. On Sundays we worked from 9am to 2pm and on Mondays from 8am to 1pm.

I learned the trade as I went on. I used to practice shaving with an old razor on a bottle – lather the bottle as if it was a chin (a very pointed chin) and shave it off. There was a lot of shaving in those days. Men used to come in regularly for their shave. They would have their own shaving mugs numbered. A man would come in and say ‘My mug is number 20.’ I’d fetch it down and lather him.

A barber’s shop was like a club in those days. People would sit and talk for hours. Some customers would come in almost every day, just for a chat. One customer I always remember was Prince Monolulu, the famous tipster, with his cry of ‘I’ve got a horse.’ His head was full of small bumps, probably fibroid growths, but his frizzy hair covered it, so that it wasn’t noticeable to the naked eye. He asked me whether I would take away a bet for him to the local street bookmaker. He wanted two shillings each way double on two horses, and he told me he didn’t want the bookmaker to know that it was his bet. Well, naturally, getting such ‘inside information’ from such a source was too good to be missed. So not only myself, but my boss, and I also prevailed upon my Dad, who was not a betting man, to join us in the bet. Needless to say both horses finished well down the field.

I’ve seen many changes here, both in the neighbourhood and in hairstyles. It used to be just a matter of short back and sides, with the occasional Boston. A Boston means the hair is cut at the back in a line, instead of gradually tapered out. Then Bostons were short, but now they are long. Before the war, of course, people wanted the sleek look. They wanted their hair slicked down. I would have men come in and want their hair brushed like Ronald Coleman’s or Raymond Navarro’s, both of whom had the patent leather look about them.

The other change has nothing to do with haircutting or shaving. The role of the barber used not to be tonsorial skills. On occasions he would become the confidant, Father Confessor, mentor and advisor of his customers, especially in sexual matters. Sexual knowledge is nowadays everybody’s right, particularly for the younger generation. But before World War Two sexual ignorance among the young was fairly high. I remember being asked for and giving advice on the functions and duties of a bridegroom. I’ve given quite a lot of advice over the years. Many were the secrets told to me in confidence of men, and their maritial and extra-marital experience, and in confidence they remained. What was more, the barber’s was the only place you could get contraceptives in those days.

Over the years I have given service to many unusual customers. There was one man who had a serious operation on this throat, with the result that one of the arteries of his throat was covered by a very thin skin, that was more red in colour than the surrounding area. He could not shave himself for fear of cutting into this thin skin and causing the artery to bleed. He warned me to be careful not to cut the thin skin as it would have been impossible for me to stop the bleeding, and he would have to go to hospital. I shaved this man three times every week, and never once did I cut his skin.

There was one aspect of my profession that always gave me a great deal of personal satisfaction, even if it did not bring me much financial reward. This was whenever it was required of me to go out and give service to customers who could not make the journey to my shop, through illness or disability. I could not leave the shop during working hours, so it meant that after closing the shop, tidying the salon, having my evening meal, then changing to go out, it was after 8pm before I left home to do this service. My charges were always very reasonable, it sometimes meant I was away from home on these evenings for up to one and half hours, and was only a few shillings in pocket. But I never minded this, as I felt it was my small contribution towards helping people who were very unfortunate.”

Lew Lessen outside the barber’s shop in Shacklewell Lane that he opened in 1932

Photographs copyright © Neil Martinson

(This interview was originally published by Centreprise as part of Working Lives, Vol 2 1945-77)

You may also like to read about

Aaron Biber, London’s Oldest Barber

Remembering Gerald Marks

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

Gerald Marks (1921-2018)

As an exhibition opens at Abbot & Holder, running until 26th November, Doreen Fletcher remembers the painter Gerald Marks to whom she was married between 1981-83.

Doreen will be in conversation with Tom Edwards at Abbot & Holder, discussing her ex-husband’s paintings on November 23rd at 6pm. Email gallery@abbottandholder.co.uk to book a ticket.

Gerald was born in Hampstead in 1921 as the only child of a middle-class liberal Jewish couple. His father was a gentle mild-mannered man who was too generous to succeed in his profession as sales representative for high-end fancy goods such as Bohemian crystal. He was always referred to by Gerald’s mum as “Poor Ferdy- a nice man but no good with money.” Liz one of Gerald’s ex-girlfriend’s told me he enjoyed having a glass of whisky with her and pinching her bottom.

His mother’s family had been wealthy, owning a carriage company in Maida Vale, but they fell on hard times when cars replaced horse-drawn vehicles at the beginning of the century. Orphaned at an early age and losing her brother in 1918 to the First World War, his mother found herself living alone in a hotel in Bayswater and struggling to earn a living as a milliner when she met Gerald’s father.

After Gerald came along, the family bought an attractive Edwardian villa in Westcliffe-on-Sea where they employed a maid and a nanny. This was normal at the time but what was unusual was that Mary continued to work, travelling to Paris and leaving Gerald in the care of his indulgent nanny. Unfortunately, this way of life ceased abruptly when Gerald was four and refused either to eat cucumber sandwiches or go to the toilet when instructed. He announced proudly that “Nanny lets me do what I want.” This domestic crisis led to nanny’s swift exit and end of Mary’s professional life.

Gerald enjoyed a carefree childhood, attending a minor public school locally. He excelled at cricket and art, and was interested in Left wing politics from a very early age. At fourteen, he exhibited at the Nationwide Children’s Royal Academy at the Guildhall, showing a drawing of an unemployed man. The image was published in the Daily Express on March 27th 1936. Gerald admitted that his political education was “the Spanish Civil War, the Depression, the rise of Fascism and mass unemployment. This was when I became a Marxist.”

Between 1938 and 1941, Gerald attended Central School of Art in London and then Northampton, where the school transferred once war was declared. Talented, popular and exceedingly good-looking, these were happy years judging by the photographs, when he made many life-long friends. Gerald joined the Communist Party in 1941 and was observed selling copies of the ‘Daily Worker’ on the streets of Northampton and thereafter monitored closely by MI5 throughout the war and perhaps beyond.

He was conscripted into the RAF’s photographic unit as a non-combative private, happily for Gerald’s survival because it was difficult to imagine him wielding a gun. Stationed in Harrogate and then Aberystwyth, Gerald was unpopular among the officers for his political stance and middle-class accent. Consequently, he was frequently given latrine duties and penalised for minor offences such as not making his bed properly. During the liberation of Europe, Gerald’s unit marched to Brussels, photographing the devastation along the way.

After the war, he received ex-serviceman’s grant to continue at Central, rejecting the Royal College as too elitist. He was taught by John Minton, Bernard Meninsky and Claude Rogers, and became involved in the Artists’ International Association Group at the Leicester Gallery, noted as an artist of great facility and potential. By the late forties, Gerald was renting a room at 13 Queens Gardens in Bayswater – a building that was to become his home and studio for the rest of his life. In 1952, he took over the top floor and, through the following decades, shared his much-loved space with a lot of young people. Gerald’s flat contained so many stories, drama, laughter and not a few tears. It could never be described as a placid environment to dwell in.

During the fifties, Gerald developed a growing reputation as a figurative painter and taught in art schools. But ,as his personal style evolved, his work was met with disapproval by the Communist Party. Gerald’s paintings of scaffolding and building workers fell short of the sentimental and naturalistic demands of Social Realism at that time. He confessed this led to his decision to quit the Communist Party, as well as the Russian invasion of Hungary in 1956.

In the sixties Gerald learned to drive, and drove with great panache until the age of eighty-six, inspiring fear and consternation amongst his passengers, many of whom only travelled with him once. He began wearing suits with bow ties, clamping an ornately-carved pipe between his teeth and his paintings became abstract, first unveiled in his solo show at the Drian Galleries in 1962.

Like his father, Gerald was no good with money and got into debt, forcing him in 1961 to take a full-time post at Croydon College of Art that lasted twenty-five years and which he believed ‘did for him’ as an artist. For twelve years, he painted very little, getting very involved in setting up teachers’ workshops and Saturday schools for young people, and he was almost fired for taking the part of the students in the 1968 lockout.

During the early seventies, Gerald started to work again on small abstract pieces and, in 1974, made the life-changing decision to buy a ruin with a tree growing through it in a remote mountainous valley in the Cevennes. He employing a team of art students, led by a fire-eater from Glasgow, who did a magnificent job constructing a roof of chestnut beams.

After Gerald retired in 1986, he spent months at a time in ‘L’Atelier’ as he called it, producing some of his best work. He had a solo show at Faroe Road Studios in 1988, culminating in a much-acclaimed exhibition at the William Jackson Galleries in 1991, entitled the ‘Madeleine Series’ – inspired by his relationship with an acclaimed violinist who spent time with him in France.

I think it is fair to say that Gerald’s three driving passions were women, art and politics in interchangeable order of importance. In 2003, he declared in an interview “Women seem to like my friendship.” They adored him but were also infuriated by him, yet even in his final months in hospital he enjoyed a significant number of female visitors.

I entered Gerald’s life in 1976 just as he was starting to exhibit again, first with the London Group then winning an Arts Council major purchase award in 1980.

I lived with Gerald for seven years and was married to him for the last two of those years. When I eventually left after some spectacular scenes, one of which included me scattering a packet of Daz over him, he said to a neighbour “How could she leave me? She knows I don’t speak French.”

Wartime London, Olympia from Kensington High St, 1940

Wartime London Refugees, 1941

London Nocturne I, Queens Gardens, Bayswater, c.1948

London Nocturne II, c.1948

Still life, c.1948

Still life, 1952

Bayswater Scaffolding II, c.1955

London Scaffolding I, 1956

Bayswater Scaffolding III, 1956

Construction Site Abstraction I, 1950s

Paintings copyright © Estate of Gerald Marks

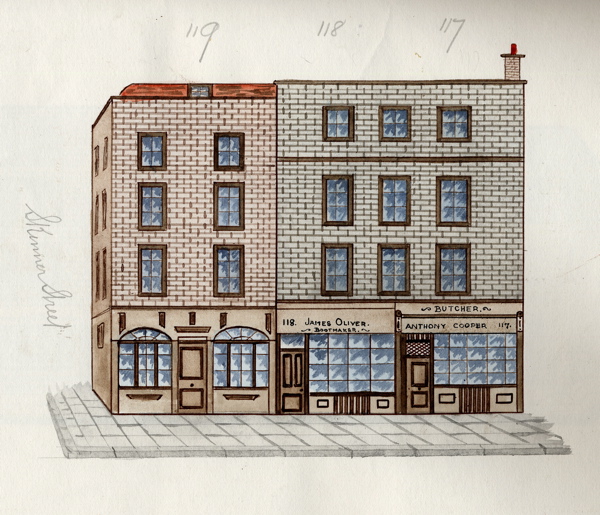

In Bishopsgate, 1838

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

Before anyone ever dreamed of Google’s Street Views, there were Tallis’s London Street Views of the eighteen thirties, “to assist strangers visiting the Metropolis through all its mazes without a guide.” John Tallis created the precedent for a map which included pictures of all the buildings as a visual aid, commissioning the unfortunately named artist Charles Bigot to do the drawings and writer William Gaspey to create the accompanying text. Tallis had his imitators, evidenced by this beautiful set of anonymous watercolours of every single facade in Bishopsgate, Spitalfields, dated to 1838 and preserved in the archive at the Bishopsgate Institute.

There is an infantile obsessive quality to these extraordinary paintings that drew my attention when I first came upon them, the degree of control and attention to detail in creating such perfect representations of the world is awe-inspiring. While there is a touching amateurism to the quality of the brushwork and lettering that recalls folk or outsider art, I cannot deny the attraction of the desire to record every facet of the world – because there is a strange reassurance to be gained from looking at these weird yet neat little pictures.

Although these views of Bishopsgate advertise their veracity by recording every single brick, I cannot believe it actually looked like this because the buildings are uniformly clean and well maintained, lacking any wear and tear. In contrast to the distorted chaotic nature of Google Street Views that record our contemporary cityscapes, there is a comic flatness in these drawings that are more reminiscent of street scenes in toy theatres and the houses you find on model railway layouts, tempting me to paste them onto matchboxes and create my own personal Bishopsgate.

Neat, tidy and eminently respectable, the early nineteenth century society envisioned by these innocuous facades is that of Adam Smith’s “nation of shopkeepers,” family businesses like that of Timothy Marr, the linen draper who opened up half a mile away upon the Ratcliffe Highway in 1808 and came to such a terrible end in 1811.

Yet although Bishopsgate itself is unrecognisably altered from the time of these drawings, the proportion of the buildings, providing a shop on the ground floor, with family accommodation and sometimes workshops above, is still familiar in Spitalfields today. And the two stocks of brick used, red brick and the London yellow brick remain the predominant colours over one hundred and fifty years later.

Sir Paul Pindar’s House, illustrated in the penultimate plate, is the lone survivor from the time before the Fire of London when Spitalfields was a suburb where aristocrats had their country residences. Today the frontage can be viewed at the Victoria & Albert Museum where it was moved in 1890.

Named Ermine St by the Romans, for centuries Bishopsgate was the major approach to the City of London from the north leading straight down to London Bridge, and the saddler & harness makers and coach builders present in the street reflect the nature of this location as a point of arrival and departure.

There are some age-old trades recorded in these pictures that survived in Spitalfields until recent times, upholsters, umbrella makers and leatherworkers, while the straw hat makers, cutlers, dyers, tallow sellers and corn dealers went long ago. Yet we still have plenty of hairdressers today, though I feel the lack of a fishmonger sorely. Let me admit, my favourite business here is Mr Waterworth, the plumber. He could become a credible addition to a set of Happy Families, along with all his little squirts.

You can see the frontage of Sir Paul Pindar’s House today at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

Maurice Evans, Pyrotechnician

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

Maurice Evans collected fireworks since childhood and at over eighty years old, he had accumulated the most comprehensive collection in the country – so you can imagine both my excitement and my trepidation upon stepping through the threshold of his house in Shoreham. My concern about potential explosion was relieved when Maurice confirmed that he had removed the gunpowder from his fireworks, only to be re-ignited when his wife Kit helpfully revealed that Catherine Wheels and Bangers were excepted because you cannot extract the gunpowder without ruining them.

This statement prompted Maurice to remember with visible pleasure that he still had a collection of World War II shells in the cellar and, of course, the reinforced steel shed in the garden full of live fireworks. “Let’s just say, if there’s a big bang in the neighbourhood, the police always come here first to see if it’s me,” admitted Maurice with a playful smirk. “Which it often isn’t,” added Kit, backing Maurice up with a complicit demonstration of knowing innocence.

“It all started with my father who was in munitions in the First World War,” explained Maurice proudly, “He had a big trunk with little drawers, and in those drawers I found diagrams explaining how to work with explosives and it intrigued me. Then came World War II and the South Downs were used as a training ground and, as boys, we went where we shouldn’t and there were loads of shells lying around, so we used to let them off.”

Maurice’s radiant smile revealed to me the unassailable joy of his teenage years, running around the downs at Shoreham playing with bombs. “We used to set off detonators outside each other’s houses to announce we’d arrived!” he bragged, waving his left hand to reveal the missing index finger, blown off when the explosive in a slow fuse unexpectedly fired upon lighting. “That’s the worst thing that happened,” Maurice declared with a grimace of alacrity, “We were worldly wise with explosives!”

Even before his teens, the love of pyrotechnics had taken grip upon Maurice’s psyche. It was a passion born of denial. “I used to suffer from bronchitis and asthma as a child, so when November 5th came round, I had to stay indoors.” he confided with a frown, “Every shop had a club and you put your pennies and ha’pennies in to save for fireworks and that’s what I did, but then my father let them off and I had to watch through the window.”

After the war, Maurice teamed up with a pyrotechnician from London and they travelled the country giving displays which Maurice devised, achieving delights that transcended his childhood hunger for explosions. “In my mind, I could envisage the sequence of fireworks and colours, and that was what I used to enjoy. You’ve got all the colours to start with, smoke, smoke colours, ground explosions, aerial explosions – it’s endless the amount of different things you can do. The art of it is knowing how to choose.” explained Maurice, his face illuminated by the images flickering in his mind. Adding, “I used to be quite big in fireworks at one time.” with calculated understatement.

Yet all this personal history was the mere pre-amble before Maurice led me through his house, immaculately clean, lined with patterned carpets and papers and witty curios of every description. Then in the kitchen, overlooking the garden lined with old trees, he opened an unexpected cupboard door to reveal a narrow red staircase going down. We descended to enter the burrow where Maurice has his rifle range, his collections, model aeroplanes, bombs and fireworks – all sharing the properties of flight and explosiveness. Once they were within reach, Maurice could not restrain his delight in picking up the shells and mortars of his childhood, explaining their explosive qualities and functions.

But my eyes were drawn by all the fireworks that lined the walls and glass cases, and the deep blues, lemon yellows and scarlets of their wrappers and casings. Such evocative colours and intricate designs which in their distinctive style of type and motif, draw upon the excitement and anticipation of magic we all share as children, feelings that compose into a lifelong love of fireworks. Rockets, Roman Candles, Catherine Wheels, Bangers, and Sparklers – amounting to thousands in boxes and crates, Maurice’s extraordinary collection is the history of fireworks in this country.

“I wouldn’t say its made my life, but its certainly livened it up,” confided Maurice, seeing my wonder at his overwhelming display. Because no-one (except Maurice) keeps fireworks, there is something extraordinary in seeing so many old ones and it sets your imagination racing to envisage the potential spectacle that these small cardboard parcels propose.

Maurice outgrew the bronchitis and asthma to have a beautiful life filled with fireworks, to visit firework factories around Britain, in China, Australia, New Zealand and all over Europe, and to scour Britain for collections of old fireworks, accumulating his priceless collection. Like an old dragon in a cave, surrounded by gold, Maurice guarded his cellar hoard protectively and was concerned about the future. “It needs to be seen,” he said, contemplating it all and speaking his thoughts out loud, “I would like to put this whole collection into a museum. I don’t want any money. I want everyone to see what happened from pre-war times up until the present day in the progression of fireworks.”

“My father used to bring me the used ones to keep,” confessed Maurice quietly with an affectionate gleam in his eye, as he revealed the emotional origin of his collection, once that we were alone together in the cellar. With touching selflessness, having derived so much joy from collecting his fireworks, Maurice wanted to share them with everybody else.

Maurice with his exploding fruit.

Maurice with his barrel of gunpowder

Maurice with his grenades.

Maurice with two favourite rockets.

Firework photographs copyright © Simon Costin

Read my story about Simon Costin, The Museum of British Folklore

David Hoffman In Cheshire St

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

Spitalfields Life Contributing Photographer David Hoffman is giving a rare free lecture, showing his superlative images of East End markets 1972-77 and talking about his experiences, this Saturday 5th November at 4pm at Bethnal Green Library as part of the Write Idea Festival.

Click here to reserve your ticket

“I was born in the East End, but my upwardly-mobile parents moved away to the green fields of Berkshire and then back to the safe suburbs of South London. By the time I drifted back to Whitechapel as a young man in 1970, I found myself in a world I had never imagined.

I encountered bomb sites still rubble-strewn from the war, smashed windows, empty shops, rubbish-scattered streets and many lost, desperate people wandering aimlessly, often clutching a bottle of cheap cider or meths. Then I was broke, unemployed and clueless, and it was scary to imagine a future amidst this dereliction.

I found a room in a damp, rickety slum in Chicksand St and began to explore, soon discovering the Sunday market in Cheshire St where I picked up a warm coat and a blanket for next to nothing. The market was surreal, with people sitting on the kerb hoping to sell a couple of old shoes and a broken razor. Other stalls were stacked with the debris of house clearance – carpets, furniture, pictures, kitchenware and books – whole lives condensed and piled up for sale.

Yet I found the market inspiring. Unregulated and chaotic, the unifying emotion was of hope bubbling through desperation. Even at the very lowest end of poverty, these people thronging the streets had got up early, pulled together a carrier bag of junk and headed off, sustained by the possibility of seeking a few pounds to get them through the next day or two. No matter how badly things had turned out, they were not giving up. It was this hope-filled resilience that buoyed me up and showed me a way forward.”

David Hoffman

Photographs copyright © David Hoffman

Save Simpsons Chop House!

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

Alas, Simpsons Chop House is under threat since the landlord shut out the staff and management as a means to force closure. Click here to help the fight to save Simpsons, London’s oldest chop house.

Occasionally I make forays into the City of London to visit some of my favourite old dining places there, and Simpsons Chop House – in a narrow courtyard off Cornhill since 1757 – is one of the few establishments remaining today where the atmosphere of previous centuries still lingers. Thomas Simpson opened his “Fish Ordinary Restaurant” in 1723 in Bell Alley, Billingsgate, serving meals to fish porters, before moving to the current site in Ball Court, serving the City gents who have been the customers ever since.

Once you pass through the shadowy passage tapering from Cornhill and emerge into the sunlight descending upon Ball Court, you feel transported into a different era, as if you might catch a glimpse of Charles Dickens and William Thackeray arriving for one of their customary lunches from the office of the Cornhill Magazine next door. Ahead of you are the two seventeenth century dwellings combined by Thomas Simpson, where a menu unchanged in two hundred and fifty years is still served upon each of the three floors, in rooms that are domestic in scale, linked by the narrow staircases of a private house.

The lunchtime rush comes late, around one, which makes midday the ideal time to arrive – permitting the opportunity to climb the stairs and explore before the City gents arrive to claim their territory with high spirits worthy of schoolboys, and, most importantly, it affords a chance to introduce yourself to the noble ladies of Simpsons, who gather in the grill room on the ground floor from around eleven thirty for a light snack and a lively chat to brace themselves before meeting their admirers.

These fine waitresses preside with such regal authority and character, they welcome customers as if they were old friends come to pay court at their personal salon or boudoir. And it is only appropriate that it should be so, since Simpsons was the first establishment to employ waitresses at the beginning of the twentieth century, even though women were not admitted as diners until 1916 – which licences the current females, making up for more than two centuries of lost time.

The redoubtable leading ladies among the coterie of Simpsons’ chop house goddesses are Jean Churcher and Maureen Thompson, who have both been here over thirty years, know all the regular customers, and carry between them the stories and the spirit of this eminent landmark, which has an atmosphere closer to that of a private lunch club than a restaurant. “I do feel like I’ve been here since the eighteenth century,” admitted Maureen, chuckling with self-effacing humour, “I’ve served three Prime Minister’s grandsons, Macmillan, Lloyd George and Churchill.”

“Midday was the bankers, one o’clock was the insurance people from Lloyds and two o’clock was the metal exchange brokers, and then they’d all mix up,” recalled Jean, waving her hands in a gesture of crazed hilarity to communicate the innumerable long afternoons of merrymaking she has seen here, in the days when banks allowed their staff to drink at lunchtime. Let them tell you tales of the old days when the chops were grilled on an ancient contraption which set the chimney on fire with such regularity that patrons would simply take up their lunch plates and copies of the Financial Times, and step out into the courtyard until the fire brigade appeared.

Before too long, the first diners arrived to interrupt our tête à tête, and I was despatched to the nether regions of the basement to meet the object of all the ladies’ affections, Scotsman Jimmy Morgan, still lithe and limber at seventy-eight, and cycling twenty miles every day thanks to a pacemaker and an artificial hip. I found Jimmy in his tiny burrow of an office deep beneath the chop house, sorting out paperwork. “I worked as a waiter at the George & Vulture next door for three years and E.J.Rose & Co, the company who were reopening Simpsons in 1978, after a two year closure, offered me the job as manager.” he explained to me politely in his lilting Glaswegian cadence,”It was a success right away, people were waiting for it to reopen. We did a free day on the first day to get in touch with all our old customers who worked around the corner.”

“I think my name’s still above the door and it’s gone all brown, it needs a wash. I was going to retire fifteen years ago but they asked me to stay on and , as my assistant manager was a friend, a waiter from the George & Vulture days, I asked if we could swap wages because I wanted him to get more money. I come in two days now. I live in New Eltham. I bicycle, I used to come by train but I’ve been coming by bike for nigh on twenty years. It takes me an hour, I tie it up on the railings and that’s it.”

There is a unique sense of community that exists at Simpsons chop house, where diners return, even long after they have retired, to maintain friendships with those they have known all their working lives.

Awaiting the lunchtime rush at Simpsons, the oldest tavern in the City of London.

Jimmy Morgan, manager since 1978, cycles ten miles from Eltham to Cornhill and back

Jean Churcher, Queen of the basement bar

In the Grill Room

Maureen Thompson, Queen of the Grill Room

The brass rails were installed for the top hats of the gentlemen of the stock exchange and the bowler hats worn by the brokers

In Ball Court

Clive Ward, manager

Emerge into the sunlight descending upon Ball Court and you feel transported into a different era

The staff of Simpsons in 1922

You might also like to read about