The Match Girls At The Hanbury Hall

It is commonly known that brave female employees of Bryant & May – known as the Match Girls – met in the Hanbury Hall in Spitalfields to form one of the very first trade unions in 1888.

There is now a rare opportunity to learn more of this auspicious event when Samantha Johnson great-granddaughter of Sarah Chapman, one of the prime movers, gives a lecture in the Hanbury Hall as part of the Spitalfields Series.

Below Samantha Johnson introduces her great-grandmother

Sarah Chapman (1862 – 1945)

My great-grandmother was born on 31st October in 1862 to Samuel Chapman and Sarah Ann Mackenzie. At the time of her birth, her father was employed as a Brewer’s Servant and was also known to have worked in the docks. The fifth of seven children, Sarah’s early years were spent at number 26 Alfred Terrace in Mile End but, by the time she was nine, the family had moved to 2 Swan Court (now the back of the American Snooker Hall on Mile End Rd), where they stayed for the next seventeen years. For a working class family at this time to stay in one place for such a long time was uncommon. Other evidence of the stability of the Chapman family is that Sarah and her siblings were educated, as they were listed as Scholars in the census and could all read and write.

At the age of nineteen, Sarah was working alongside her mother and her older sister, Mary, as a Matchmaking Machinist, and by 1888 she was an established member of the workforce at the Bryant & May factory in Bow. At the time of the Strike, Sarah is listed as working in the patent area of the business, as a Booker, and was on relatively good wages, which perhaps placed her in a position of esteem among other workers. She was certainly paid more than most and this may have been because of her position as a Booker, or perhaps because she just managed to avoid the liberal fines which were meted out by the employers.

There was a high degree of unrest in the factory due to the low wages, long hours, appalling working conditions and the unfair fines system, which caused the women at the factory to grow increasingly frustrated. External influences, particularly the Fabian Society, also provided an impetus for the Strike. Ultimately, 1400 girls and women marched out of the factory, en masse, on that fateful day of 5th July 1888. The next day some 200 girls marched from Mile End down to Bouverie St in the Strand to see Annie Besant, one of the Fabians and a campaigner for women’s rights. A deputation of three (my great-grandmother Sarah Chapman, Mrs Mary Cummings and Mrs Naulls) went into her office to ask for her support. Although Annie was not an advocate of strike action, she did agree to help them organise a Strike Committee.

“We’d ‘ave come out before only we wasn’t agreed”

“You stood up for us and we wasn’t going back on you”

The first meeting of the striking Matchgirls was held on Mile End Waste on 8th July and both the Pall Mall Gazette and The Star provided positive publicity. This was followed by meetings with Members of Parliament at the House of Commons. The Strike Committee was formed and the following Match Girls were named as members: Mrs Naulls, Mrs Mary Cummings, Sarah Chapman, Alice Francis, Kate Slater, Mary Driscoll, Jane Wakeling and Eliza Martin.

Following further intervention by Toynbee Hall and the London Trades Council, the Strike Committee was given the chance to make their case. They met with the Bryant & May Directors and by 17th July, their demands were met and terms agreed in principle. It was agreed that:

- All fines should be abolished.

- All deductions for paint, brushes, stamps, etc., should be put an end to.

- The 3d. should be restored to the packers.

- The “pennies” should be restored or an equivalent advantage given in the system of payment of the boys who do the racking.

- All grievances should be laid directly before the firm, before any hostile action was taken.

- All the girls to be taken back.

It was also agreed that a union be formed, that Bryant & May provide a room for meals away from where the work was done and that barrows be provided to transport boxes, replacing the practice of young girls having to carry them on their heads. The Strike Committee put the proposals to the rest of the workforce and they enthusiastically approved. Thus the inaugural meeting of the new Union of Women Match Makers took place at Stepney Meeting Hall on 27th July and twelve women were elected, including Sarah Chapman.

An indicator of the belief her fellow workers put in Sarah’s ability, was her election as the first TUC representative of the Match Makers’ Union. Sarah was one of seventy-seven delegates to attend the 1888 International Trades Union Congress in London and at the 1890 TUC she is recorded as having seconded a motion.

On the night of the 1891 census, Sarah was still a Booker at the match factory and living with her mother in Blackthorn St, Bromley by Bow, but in December of that same year, she married Charles Henry Dearman, a Cabinet Maker. By this time she had ceased working at Bryant & May.

Sarah and Charles had their first child, Sarah Elsie in 1892. They had five more children, one was my grandfather, William Frederick, born in 1898 when they had moved to Bethnal Green. Sarah’s two youngest sons, William and Frederick lived with her, on and off, into the thirties and she lived out her years there, dying in Bethnal Green hospital on 27th November 1945 aged eighty-three. She was survived by three of her six children, Sarah, William and Fred.

Sarah was buried alongside five other elderly people in a pauper’s plot at Manor Park Cemetery. It was a sad end to a brave life filled with challenges, not least a leading role in a Strike that was the vanguard of the New Labour Movement and helped establish Trade Unionism in this country.

It is thanks to Anna Robinson, Poet & Lecturer at the University of East London, who chose Sarah Chapman as the topic of her MA thesis, Neither Hidden Nor Condescended To: Overlooking Sarah Chapman, that I discovered the story of my great-grandmother. I contacted Anna in 2016 after I discovered her post on a family history forum appealing for information. Until then, I had no idea about Sarah’s story.

Sarah as a member of the Match Girls Union Committee

Sarah with her husband Charles Henry Dearman

Sarah with her grandson, Frederick William

Sarah in later years

You may also like to take a look at

In Old Bermondsey

The horse’s head upon the fascia reveals that RW Autos was once a farrier

Thirty years ago I had reason to visit Bermondsey St frequently but I have hardly been there since, so I thought it was time to walk down across the river and take a look. Leaving the crowds teeming like ants upon the chaotic mound that is London Bridge Station, I ventured into Guy’s Hospital passing the statue of Thomas Guy, who founded it in 1721, to sit with John Keats in a stone alcove from old London Bridge now installed in a courtyard at the back.

From here, I turned east through the narrow streets into Snowsfields, passing the evocatively named Ship & Mermaid Row, and Arthur’s Mission of 1865 annotated with “Feed my Lambs” upon a plaque. An instruction that has evidently not been forgotten, as the building adjoins the Manna Day Centre which offers refuge and sustenance to more than two hundred homeless people each day.

At the end of Snowsfields is the crossroads where Bermondsey St meets the viaduct carrying the railway to and from London Bridge, and the sonorous intensity of the traffic roaring through, combined with the vibration from the trains rattling overhead, can be quite overwhelming. Yet the long narrow street beckons you south, as it has done for more than a thousand years – serving as the path from the Thames to the precincts of Bermondsey Abbey, a mile away, since the eleventh century. When I first came here, I never ventured beyond Bermondsey Sq. Only when I learned of the remains of the medieval gatehouse in Grange Walk beyond, with the iron hinges still protruding from the wall today, did I understand that Bermondsey St was the approach to the precincts of the Abbey destroyed by Henry VIII in 1536.

There is an engaging drama to Bermondsey St with its narrow frontages of shops and tall old warehouses crowded upon either side, punctuated by overhanging yards and blind alleys. Thirty years ago, everything appeared closed down, apart from The Stage newspaper with its gaudy playbill sign, a couple of attractively gloomy pubs and some secondhand furniture warehouses. I was fascinated by the mysteries withheld and Bermondsey St lodged in my mind as a compelling vestige of another time. Nowadays it appears everything has been opened up in Bermondsey St, and the shabbiness that once prevailed has been dispelled by restoration and adaptation of the old buildings, and the addition of fancy new structures for the Fashion & Textile Museum and the White Cube Gallery.

Yet, in spite of the changes, I was pleased to discover RW Autos still in business in Morocco St with the horses’ heads upon the fascia, indicating the origin of the premises as a farrier. Nearby, the massive buildings of the former London Leather Exchange, now housing dozens of small businesses, stand as a reminder of the tanning industry which occupied Bermondsey for centuries, filling the air with foul smells and noxious fumes, and poisoning the water courses with filth.

The distinctive pattern of streets and survival of so many utilitarian nineteenth and eighteenth century structures ensure the working character of this part of Bermondsey persists, and you do not have to wander far to come upon blocks of nineteenth century housing and old terraces of brick cottages, interspersed by charity schools and former institutes of altruistic endeavour, which carry the attendant social history. Thus Bermondsey may still be appreciated as an urban landscape where the past is visibly manifest to the attentive visitor, who cares to spend a quiet afternoon exploring on foot.

John Keats at Guy’s Hospital

Arthur’s Mission in Snow’s Fields seen from Guinness Buildings 1897

In Bermondsey St

At the Woolpack

Old warehouses in Bermondsey St

St Mary Magdalen Bermondsey – the medieval tower is the last remnant of the Abbey founded in the eleventh century

In St Mary’s Bermondsey St

In St Mary Magdalen Graveyard

This plaque marks the site of the abbey church

Old houses in Grange Walk – the house on the right is claimed to be the Abbey gatehouse with hinges of the gates still visible

Bermondsey United Charity School for Girls in Grange Walk, 1830

In Grange Walk

Bermondsey Sq Antiques Market every Friday

A cottage garden in Bermondsey

The Victoria, a magnificent tiled nineteenth century pub with its original spittoon, in Pages Walk

London Leather, Hide & Wool Exchange built 1878 by George Elkington & Sons, next to the 1833 Leather Market, it remained active until 1912.

You may also like to take a look at

Roy Wild, Van Boy

Roy looking sharp in the fifties – “I class myself as an Hoxtonite”

The great goodsyard in Bishopsgate is an empty place these days, home to a pop-up shopping mall of sea containers and temporary football pitches, but Roy Wild knew it in its heyday as a busy rail depot teeming with life and he still keeps a model of the Scammell Scarab that he once drove there as a talisman of those lost times.

A vast nineteenth century construction of brick and stone, the old goodsyard housed railway lines on multiple levels and was a major staging point for freight, with deliveries of fresh agricultural produce coming in from East Anglia to be sold in the London wholesale markets and sent out again across the country. Today only the fragmentary Braithwaite arches of 1839 and the exterior wall of the former Bishopsgate Station remain as the hint of the wonders that once were there.

Roy knew it not as the Bishopsgate Goodsyard but in the familiar parlance of railway workers as ‘B Gate,’ and B Gate remains a fabled place for him. By their very nature, railways are places of transition and, for Roy Wild, B Gate won a permanent place in his affections as the location of formative experiences which became his rite of passage into adulthood.

“At first, after I left school at fifteen, I went to work for City Electrical in Hoxton and I was put as mate with a fitter named Sid Greenhill. One of the jobs they took on was helping to build the Crawley new town. We had to get the bus to London Bridge, take the train to East Croydon and change to another near Gatwick Airport – which didn’t really exist yet. It was a schlep at seven o’clock in the morning all through the winter, but I stuck it for eighteen months.

My dad, Andy, was a capstan operator for the London & North Eastern Railway at the Spitalfields Empty Yard in Pedley St off Vallance Rd, so I said to him, ‘Can’t you get a job for me where you work?’ He said, ‘There’s nothing going at the moment but I can get you a place at B Gate.’

In 1953, at sixteen and a half, I started as van boy for Dick Wiley in the cartage department at B Gate. The old drivers had worked with horses, they were known as ‘pair-horse carmen’ or ‘single-horse carmen’ and, in the late forties when the horses were done away with and the depot became mechanised, the men were all called in and given three-wheeled Scammell Scarabs and licences, no driving tests in those days. There was a fleet of two hundred of them at B Gate and although strictly, as van boys, we weren’t allowed to drive, we flew around the depot in them.

Our round was Stoke Newington and we’d be given a ticket which was the number of your container and a delivery note of anything up to twenty-five destinations. Then we’d have lunch at a small goods yard at Manor Rd, Stoke Newington, and in the afternoon we’d do collections, picking up parcels and taking them back to B Gate, from where they’d be delivered by rail around the country.

I decided I wanted to work with George Holman, a driver who was known as ‘Cisco’ on account of his swarthy features which made him look Mexican. He was an East Ender like me, rough and ready, and always larking about. His round was Rotherhithe which meant driving through the tunnel and he was a bit of a lunatic behind the wheel. Each morning after the round, he would drop me off at my mum’s in Northport St for lunch and pick me up again at 2pm. One day, we had to go back through ‘the pipe’ as they called the tunnel in Mile End and he said to me, ‘You take it through the tunnel, you know how it works.’ I was only seventeen but I drove that great big truck through the tunnel without any harm whatsoever.

Next I went to work with Bill Scola, a driver from Bethnal Green – the deep East End. He used to do Billingsgate, Spitalfields, Borough, Covent Garden, Brentford and Nine Elms Markets. Bill was a rascal and I was nineteen by then. We were doing a bit of skullduggery and I was told that the British Transport Police were watching me, so I said to Bill, ‘Things are getting too hot,” and I left it alone completely.

Then, one day we were having breakfast with at least a dozen others at the table, including Sid Green who was in charge of Bishopsgate football team, in the new canteen at B Gate when the British Transport Police came in, pinned my arms against my side and lifted me out of the chair. I was taken across to Commercial St Police Station and charged with larceny. They told me I had been seen lifting goods into the van that weren’t on the parcels sheet, with the intention of taking and selling them. I said I didn’t know what they were talking about. What were they were alleging was a complete fabrication and I had witnesses. What they were accusing me of was impossible because I had just clocked in – my clocking in number was 1917 – and there was a least a dozen witnesses on my side, but nevertheless I was convicted. I look back on it with great regret even now.

I was taken to Newington Butts Quarter Sessions which was the nearest Crown Court and I received six months sentence, even though I had first class character witnesses. I was taken straight to Wormwood Scrubs but kept apart from the inmates as a Young Prisoner. I couldn’t believe it, this was a for a first offence. I was sent to East Church open prison on the Isle of Sheppey and given a third remission off my sentence for good behaviour. It was like a Butlins Holiday Camp and I came home after four months. After that I did a couple of odd jobs, but I was full of regret – because I loved the railway so much and I made so many friends there, and particularly because I had disappointed my dad. That was the end of me and the LNER.

Then I met this guy, Billy Davis, he and Patsy (Patrick) Murphy held up Luton Post Office, but the postmaster grabbed hold of the gun and they shot and killed him, and they both got twenty-five years. He told me he worked for the railway and I asked, ‘Which depot?’ He said, ‘London, Midlands & Scottish Railway in Camden, why don’t you apply?’ So I did, I went along to Camden Town and was interviewed and told them I’d never worked on the railway before. When I started there as a driver, they gave me a brand new Bantam Carrier with a trailer and my round was Spitalfields Market, and I was paid by tonnage. The more weight you pulled onto the weighbridge at the Camden Town LMS depot, the more you earned.

I did it for some time and I always had plenty of fruit to take home to my mum. I got together with the Goods Agent’s secretary, he was the top man in the depot and I was on good terms with him too. I got very friendly, taking her out for more than a year, until one day she told me her boss wanted to see me in his office. He said to me, ‘I’ve got bad news – you never declared you were dismissed by LNER. Our security have run a check and they found it out. It’s gone above my head and I have to let you go. It’s all out of my hands.’ He told me he was sorry to see me go because of the amount of tonnage I brought in which was more than other driver.

I was only there eighteen months. It was the finest time of my life because of the camaraderie with all the other drivers. It was a lovely, lovely job and I made friends that I still have to this day.”

Roy Wild with a model of his beloved Scammell Scarab

Roy with a Scammell Scarab in British Rail livery

Colin O’Brien’s photograph of a Scammell Scarab tipped over on the Clerkenwell Rd, 1953

Roy gets into the cabin of a Scamell Scarab of the kind he used to drive at Bishopsgate Goodsyard

Roy’s father Andy worked as a Capstan Operator at Spitalfields Empty Yard at Pedley St off Vallance Rd

Roy Wild & lifelong pal Derrick Porter, the poet – “I came from Hoxton but he came from Old St”

Bishopsgate Station c. 1900

In its heyday the area of tracks at the goodsyard was known as ‘the field’

Looking west, the abandoned goodsyard after the fire of 1964

Looking east, the abandoned goodsyard after the fire

The kitchens of the canteen at the goodsyard

The space of the former canteen where Roy was arrested by the British Transport Police

Abandoned hydraulic lift for lifting vehicles at Bishopsgate goodsyard

The remains of the records at the Bishopsgate goodsyard

When Roy saw this photograph of the demolished goodsyard, he said, “I wish I could have gone and taken one of those bricks as a souvenir.”

The arch beneath the white tarpaulin was where Roy once drove in and out as a van boy

You may also like to read about

Viscountess Boudica On Valentine’s Day

On Valentine’s Day, I cannot help thinking back to the days when we had Viscountess Boudica of Bethnal Green to make the East End a more colourful place, before she was ‘socially cleansed’ to Uttoxeter

Viscountess Boudica of Bethnal Green confessed to me that she never received a Valentine in her entire life and yet, in spite of this unfortunate example of the random injustice of existence, her faith in the future remained undiminished.

Taking a break from her busy filming schedule, the Viscountess granted me a brief audience to reveal her intimate thoughts upon the most romantic day of the year and permit me to take these rare photographs that reveal a candid glimpse into the private life of one of the East End’s most fascinating characters.

For the first time since 1986, Viscountess Boudica dug out her Valentine paraphernalia of paper hearts, banners, fairylights, candles and other pink stuff to put on this show as an encouragement to the readers of Spitalfields Life. “If there’s someone that you like,” she says, “I want you to send them a card to show them that you care.”

Yet behind the brave public face, lay a personal tale of sadness for the Viscountess. “I think Valentine’s Day is a good idea, but it’s a kind of death when you walk around the town and see the guys with their bunches of flowers, choosing their chocolates and cards, and you think, ‘It should have been me!'” she admitted with a frown, “I used to get this funny feeling inside, that feeling when you want to get hold of someone and give them a cuddle.”

Like those love-lorn troubadours of yore, Viscountess Boudica mined her unrequited loves as a source of inspiration for her creativity, writing stories, drawing pictures and – most importantly – designing her remarkable outfits that record the progress of her amours. “There is a tinge of sadness after all these years,” she revealed to me, surveying her Valentine’s Day decorations,” but I am inspired to believe there is still hope of domestic happiness.”

Take a look at

The Departure of Viscountess Boudica

Viscountess Boudica’s Domestic Appliances

David Hoffman At St Botolph’s In Colour

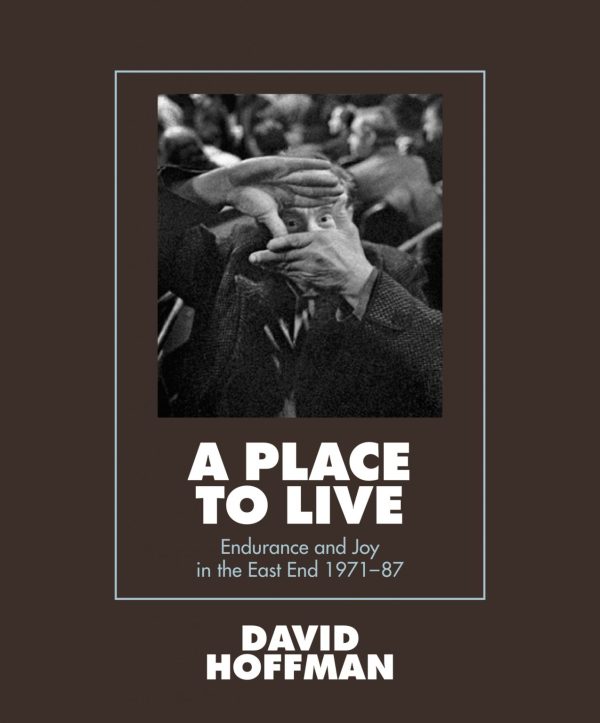

David Hoffman undertook a significant body of photography documenting the East End in the seventies and eighties that I plan to publish this year as a book entitled, A PLACE TO LIVE, Endurance & Joy in Whitechapel, accompanied by a major photographic exhibition at House of Annetta in Spitalfields.

I believe David’s work is such an important social document, distinguished by its generous humanity and aesthetic flair, that I must publish a collected volume. I have a growing list of supporters for this project now, so if you share my appreciation of David’s photography and might consider supporting this endeavour, please drop me a line at spitalfieldslife@gmail.com

Contributing Photographer David Hoffman sent me this dramatic set of photographs that he took at the ‘wet shelter’ for homeless people – where alcohol and drugs were permitted – in the crypt of St Botolph’s Church, Aldgate, in the seventies. Readers will recall David’s series of black and white pictures of St Botolph’s shelter that I published last week, recording Rev Malcolm Johnson’s compassionate initiative offering refuge to the dispossessed without distinction.

These colour photographs make a fascinating contrast to the monochrome realism of David’s earlier series, offering a distinctive vision of the same subject that is both more emotive and visceral, yet also more painterly and even lyrical.

“These were shots undertaken as tests as much as documenting the wet crypt. The light was a mix of coloured fluorescent tubes and tungsten bulbs, and the types of film available that were sensitive enough to use in this relatively-dark environment also varied a lot in their sensitivity to different-coloured lighting – all of which made for unpredictable results as I moved around, and the push-processing required gave a lot of grain which cut down the sharpness I could achieve.

In those days, I was keen to show off my technical skills and didn’t really like the effect – so I quickly gave up using colour and returned to black and white. But, looking back at these pictures now, I wonder what I was thinking. I find the colour shifts and graininess quite gorgeous and I regret not taking the idea further.”

– David Hoffman

Photographs copyright © David Hoffman

John Thomas Smith’s Antient Topography

Bethelem Hospital with London Wall in Foreground – Drawn June 1812

Two centuries ago, John Thomas Smith set out to record the last vestiges of ancient London that survived from before the Great Fire of 1666 but which were vanishing in his lifetime. You can click on any of these images to enlarge them and study the tender human detail that Smith recorded in these splendid etchings he made from his own drawings. My passion for John Thomas Smith’s work was first ignited by his portraits of raffish street sellers published as Vagabondiana and I was delighted to spot several of those familiar characters included here in these vivid streets scenes of London long ago.

Click on any of these images to enlarge

Bethel Hospital seen from London Wall – Drawn August 1844

Old House in Sweedon’s Passage, Grub St – Drawn July 1791, Taken Down March 1805

Old House in Sweedon’s Passage, Grub St – Drawn July 1791, Taken Down March 1805

London Wall in Churchyard of St Giles’ Cripplegate – Drawn 1793, Taken Down 1803

Houses on the Corner of Chancery Lane & Fleet St – Drawn August 1789, Taken Down May 1799

Houses in Leadenhall St – Drawn July 1796

Duke St, West Smithfield – Drawn July 1807, Taken Down October 1809

Corner of Hosier Lane, West Smithfield – Drawn April 1795

Houses on the South Side of London Wall – Drawn March 1808

Houses on West Side of Little Moorfields – Drawn May 1810

Magnificent Mansion in Hart St, Crutched Friars – Drawn May 1792, Taken Down 1801

Walls of the Convent of St Clare, Minories – Drawn April 1797

Watch Tower Discovered Near Ludgate Hill – Drawn June 1792

An Arch of London Bridge in the Great Frost – Drawn February 5th 1814

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana

Spring Bulbs At Bow Cemetery

Already I have some snowdrops and hellebores in flower in Spitalfields, but at Bow I was welcomed by thousands of crocuses of every colour and variety spangling the graveyard with their gleaming flowers. Beaten and bowed, grey-faced and sneezing, coughing and shivering, the winter has taken it out of me, but feeling the warmth of the sun and seeing these sprouting bulbs in such profusion restored my hope that benign weather will come before too long.

Some of my earliest crayon drawings are of snowdrops, and the annual miracle of spring bulbs erupting out of the barren earth never ceases to touch my heart – an emotionalism amplified in a cemetery to see life spring abundant and graceful in the landscape of death. The numberless dead of East London – the poor buried for the most part in unmarked communal graves – are coming back to us as perfect tiny flowers of white, purple and yellow, and the sober background of grey tombs and stones serves to emphasise the curious delicate life of these vibrant blooms, glowing in the sunshine.

Here within the shelter of the old walls, the spring bulbs are further ahead than elsewhere the East End and I arrived at Bow Cemetery just as the snowdrops were coming to an end, the crocuses were in full flower and the daffodils were beginning. Thus a sequence of flowers is set in motion, with bulbs continuing through until April when the bluebells will come leading us through to the acceleration of summer growth, blanketing the cemetery in lush foliage again.

As before, I found myself alone in the vast cemetery save a few magpies, crows and some errant squirrels, chasing each other around. Walking further into the woodland, I found yellow winter aconites gleaming bright against the grey tombstones and, crouching down, I discovered wild violets in flower too. Beneath an intense blue sky, to the chorus of birdsong echoing among the trees, spring was making a persuasive showing.

Stepping into a clearing, I came upon a red admiral butterfly basking upon a broken tombstone, as if to draw my attention to the text upon it, “Sadly Missed,” commenting upon this precious day of sunshine. Butterflies are rare in the city in any season, but to see a red admiral, which is a sight of high summer, in February is extraordinary. My first assumption was that I was witnessing the single day in the tenuous life of this vulnerable creature, but in fact the hardy red admiral is one of the last to be seen before the onset of frost and can emerge from months of hibernation to enjoy single days of sunlight. Such is the solemn poetry of a lone butterfly in winter.

It may be over a month yet before it is officially spring, but we are at the beginning now, and I offer you my pictures as evidence, should you require inducement to believe it.

The spring bulbs are awakening from their winter sleep.

Snowdrops.

Crocuses

Dwarf Iris

Winter Aconites

Daffodils will be in flower next week.

A single Red Admiral butterfly, out of season in February – “sadly missed”

Find out more at Friends of Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park

You may also like to read about